Chapter Eight. Service Innovation: Breakthrough Innovation on the Product–Service Ecosystem Continuum

Services are intangible. You buy them and use them, but you don’t take them home. Yet the service sector accounts for more than 65% of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP). Navigating the Fuzzy Front End of service design is no different than doing so for physical products. However, the new opportunity for the twenty-first century is to recognize that an ecosystem of physical products and intangible services working in concert and supporting each other is where breakthrough innovation lies. Designing services within the context of that ecosystem is the topic of this chapter.

The Era of Interconnected Ecosystems: Product, Interface, and Service

During the last two centuries the U.S., Europe, and Japan evolved from agrarian, craft-based economies into manufacturing economies. Service and information companies evolved as well, but the primary emphasis was on creating new companies based on technology innovation as their core capability. The telephone was the focus for the consumer, even though the communication system was the key to delivering phone calls. The Ford assembly line produced affordable cars, and the new system of manufacture was second to the success and sales of the Model T. No one thought about the road infrastructure system, or the energy system needed to support the growth of vehicles, or the fact that when the U.S. focused on roads, it de-emphasized railroads. Edison discovered the filament to make electric lights affordable, but he also developed an electric distribution system for direct current to bring power to home and business. Carnegie is recognized for steel production, but he also developed the idea of vertical integration, from raw material to the trains and tracks needed to ship raw material and deliver finished steel. These men were celebrated for their ability to bring greater access to products for a growing middle class and to generate profits. Ford Motor Company, Edison General Electric, and U.S. Steel could have just as easily been considered the founding of the U.S. service systems industry.

The financial services sector has always been part of the growth of the manufacturing economy and is represented by people such as J. P. Morgan, who brought a new scale to the banking investment capability in the United States. The information economy evolved to manage the rise of the large modern corporation.

Information systems did not start to catch up with manufacturing scale until after World War II, when IBM was the first to see the potential in computers to handle vast amounts of data required to manage modern global corporations. Even then modern mainframe facades hid the kluge of wires driving IBM computers. Hardware was the focus and the anticipated means for innovation. IBM told Bill Gates he could keep the software he was developing because IBM was not in the software business. When Gates left IBM after that fateful meeting, he started Microsoft, and information software as a major industry was born—and would eventually trump hardware products in much of the computer industry. Historically, the service economy was the supportive entity of new product development and took second stage to the celebration of the product as a standalone demonstration of the consumer society. The service economy, information economy, and product development economy were viewed as separate. When people thought about banks, health insurance, schools, or the post office, there were possibly new product offerings that extended the service directly, but none of these were seen as sources for physical product innovation or innovation at the system level that integrated new types of physical, software, and service capabilities.

Most products developed before the end of the twentieth century were one dimensional; they did one thing well and were not directly connected to any service or information service system. The rise of the Web, the desktop, the smartphone, micro sensors, and GPS has changed the rules of the game. Steve Jobs and Apple connected the products of IBM, the software of Microsoft, and the research of Xerox to the new capabilities of the Web to eventually produce the integration into a system that is now the new standard.

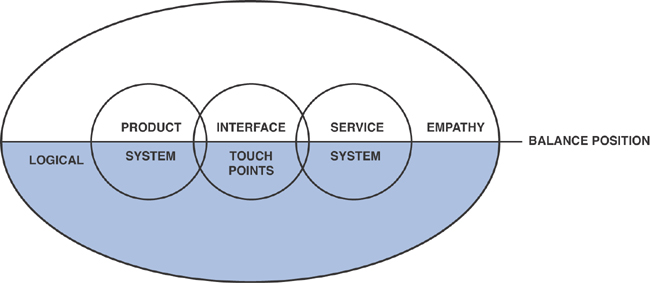

In the first edition of the book, we discussed the relationship between products and services and showed that the early stage development of both is the same. During the last decade, this relationship has grown and become interconnected in powerful new ways. Product systems and service systems can no longer be discussed as separate. The opportunity for innovation is in creating new businesses where products, services, and interface are seen as interconnected parts of the value and profit in any new idea. Every product is connected to a service system, and every system relies on products to deliver value to consumers. Every product and service has an interface or touch points. The interface touch points can be tangible product controls, digital, human, or any combination of the three. The interface defines the way people interact with the services and physical products. Figure 8.1 shows this model.

Figure 8.1. The relationship of products, services, and interfaces.

This model emerged as every major new product evolved either to have embedded intelligence connecting to external services or to have a digital service system that supports it. Smartphones are clear examples; today the smartphone is one product in an interconnected web of products and services that connect phone to computer to social media. Cars are now another example: OnStar, GPS, and other services connect the car to a network of information and services. Services, too, have multiple touch points that either rely on overt physical product touch points or are re-inforced by products. UPS has trucks and scanning products that delivery people use, but it also has planes, trucks, and integrated tracking products that work behind the scenes of deliveries or stores.

So three levels of systems are important to consider. Physical product development systems are one type of system in this book. Physical product systems relate to the process required to conceive of and deliver a tangible product to the market and maintain the product as a competitive offering. Navistar’s LoneStar is a case study of a physical product development system. Service systems relate to the process of conceiving of and delivering a service offering and maintaining it as a competitive offering. Starbucks is an example of a service system.

The third system is the higher-level interconnection of the intangible service and physical product systems. This interconnection enables a new level of value, the means to deliver the needs, wants, and desires of the customer in a deeper and more complete manner, and with different models of revenue streams. In this model, iTunes and iCloud provide connectivity of Apple products through people’s daily lives, along with ongoing revenue streams. Also in this model, Amazon designs and sells the Kindle, a physical product, as a means to enable e-book purchases through the Web.

There is generally an emphasis on the tangible or intangible in a company. On one hand, the physical product is the focus and the service is the support that helps differentiate and generate profit for the company. Ford makes cars, but cars are now “driven” by internal systems connecting one part of the car to the other and to the driver/owner. Cars now connect externally to a host of services supporting the driving experience. The value of the vehicle as a product to get from one place to another is complemented by the new interactive services that a driver can access while traveling. On the other hand, the service is the focus of the system and provides less tangible value to customers as its core value. Google is now developing a car that will use its services and interface to create a driverless vehicle. So is Ford a service company and Google a product development company? The answer is yes to both situations. Some companies seek to balance the tangible and intangible. Apple is a great example. They make profit on the hardware, but also from the linked services including iTunes, iCloud, and the iPhone plans. UPS generates profits through their intangible services, but they must invest in a significant number of physical products to provide that service.

Delivering packages, insurance, health care services, smartphone apps, cable TV, and government agencies are examples of services. They require a variety of touch points working in harmony to deliver their value to customers. Cable TV is an invisible supplier to the monitor in your home, but it still requires a cable box. If you have any problems, an installer/repairman shows up at your door. He has tangible cable that is required to connect to your television. He arrives in a truck and has a variety of tools to install your cable in your home or repair your cable box or connection from your home to the street. An army of people and offices supply that service to you, yet you never see them when you are watching your favorite HBO series or sports event.

The challenge in developing new innovative offerings is to understand the tangible and intangible systems that drive your product or service and how to effectively integrate all aspects to deliver brand equity to maintain customer loyalty.

New innovative offerings require the integration of tangible and intangible systems to deliver brand equity to maintain customer loyalty.

Empathy Versus Logic

Two aspects must be balanced to deliver a brand experience through the product, service, and interface system. The logical aspect accounts for the quantitative and analytical aspects of the system. This includes cost and price analysis, technology, durability and safety, benchmarking of competition, and cost cutting. The empathetic aspect accounts for the qualitative and human side of the system. This includes emotion, aspiration, fantasy, personality, style, and connection between people. In practice, all good companies balance the logical and empathetic aspects of their system. The value proposition of an Upper Right company or product naturally balances these attributes, as captured in the VOA. Generally, the emotion, aesthetic, impact, and identity terms are empathetic. The quality and core technology are logical. Ergonomics has both logical and empathetic characteristics, the logical being the anthropometric and analytical approach to assessing reach and physical interaction, and the empathetic being the feel and sense of the space. Price and profit are also logical and are byproducts of a successful value proposition.

However, some companies choose to emphasize logical or empathy aspects in their branding and messaging. Internally, Apple is a balance between empathic and logical. However, to consumers, the brand perception is that the empathic understanding is stronger than the logical: Apple is part of your lifestyle and life. It is an Upper Right company. The company that emphasizes the logical without regard to the empathetic generally is the Lower Right or Lower Left brand, emphasizing cost or technical performance. HP is a company that is respected for the logic of its business machines. The consumer perception of the brand for HP is in the Lower Right. Dell is known for its price and speed of delivery and is perceived to be in the Lower Left. The company that emphasizes empathy without regard to logic is the Upper Left brand, emphasizing style and fashion alone.

The goal, then, is to recognize that your product or service is part of a larger system, and that larger system is often the bigger business opportunity. Addressing the bigger opportunity requires a plan that is more than the development of one product, one feature, or one touch point. Instead, the bigger system requires a larger strategy. Amazon.com began as an online retailer of books. The larger plan was to be a point of sale for anything consumer on the Internet and to broaden beyond virtual to physical products such as the Kindle. Even when profits were down, CEO Bezos maintained his vision and his system-level plan. The result is one of the more successful companies of the twenty-first century.

The second aspect of the system is to recognize the value of empathy and its balance with logic. That is one of the main points of this book and is equally valid for tangible products, intangible services, and the larger system of both. As you see throughout this chapter, the methods of identifying opportunities, understanding those opportunities, and conceptualizing those opportunities apply equally to all of these models: physical product, service, and system.

Traditional Service Design

Services are the intangible means to provide value, often through activities or accommodation. The U.S. Census Bureau considers the service sector to consist primarily of truck transportation, messengers, warehousing, and storage; information services, financial securities and brokerage, and rental and leasing services; professional, scientific, and technical services; administrative and support services; waste management and remediation; health care and social assistance; and arts, entertainment, and recreation services. Customers don’t own the service, and the service tends to be consumed at the point of sale. Yet services are estimated to account for between 65% and 75% of the U.S. GDP.1

Consider what some might think of as the ultimate service: the Ritz-Carlton. At the Ritz, you don’t take anything home with you; you don’t own any product you buy. Yet you pay a hefty price for the luxury that comes from staying there. Horst Schulze, founding president and COO, recognized that you don’t even go to the Ritz to just sleep or eat. “In the case of the bar,” when referring to the bartenders, “customers are entering your room, but they are not coming for you. They are not coming to drink—they have drinks in their rooms and at home. They are not coming to eat. They are coming to feel well. ... Your ultimate responsibility is that each guest feels well when they leave because of how you enhanced their life in the moment that you had to serve them.”2 You go to the Ritz because of the exceptional service it provides, because every person there makes you feel great. The design of that service requires understanding the value proposition—how you feel, the senses that you experience through your interaction with all aspects of the service, the ease of interaction, its consistency and attention to details, the social interactions you might have there, and the unique look and feel that the Ritz consistently provides in each and every stay. In sum, the Ritz succeeds because it understands the value attributes captured in the VOA. The Ritz is clearly positioned in the Upper Right, providing an interactive experience unlike any other and luxurious style that pampers every guest, differentiating itself from other hotels through its highly valued service.

Although all of the tools and methods presented in this book to navigate the Fuzzy Front End apply equally to physical products, services, and systems, the traditional service might differ from the physical product at the level of implementation. The physical product must be built with materials, and production typically accounts for mass or at least multi-unit production. The service is not physically built, but is instead planned, detailed, and modeled. It results in a step-by-step process to perform the service. As with a physical product, the service must be prototyped and tested, both through anticipated uses and with actual customers.

Although at first glance the service industry might appear very much focused on people and not technology, in all facets of service, technology plays an active and often critical role. From UPS, which spends more than $1 billion per year on technology; to interaction design that focuses on technology interfaces; to Disney movies using CGI, technology abounds. Even with law firms, rooted in the ability for a lawyer to effectively convince a jury of innocence or guilt for the accused, technology comes into play: Depositions are searched and projected during a trial with the hope of catching a witness off-guard so that the person might perjure him or herself. Thus, with more than half the GDP based in service industries, opportunities for innovation abound not only in the services themselves, but also in the technology that supports them.

In the rest of this chapter, we explore a range of services and product–service systems to better understand how to navigate the Fuzzy Front End in this context. We begin with a traditional service, the banking industry, by looking at the design of Umpqua Bank. You will see that, even in the realm of traditional services, the opportunity to address the larger product–service system presents an opportunity for breakthrough innovation. Next, we explore another traditional service, package delivery and logistics, through UPS, again recognizing the extensive use of physical products to enable the delivery of the service. We also look at the entertainment industry by discussing one aspect of the ultimate entertainment service: Disney. Interaction design, more general than just for services, but particularly critical for the success of services, is explored next. Together, these discussions and case studies show the opportunity to approach service design with the same rigor and organization as the design of any other product, and focus on the product–service ecosystem as the broader opportunity for growth and innovation.

Umpqua: Designing a Bank Like a Product

Banks have been one of the anchors of the financial services industry for centuries. During the last 50 years, banks in the U.S. have had to continue to evolve. Bank facades used to look like government buildings, with clear references to Greek or Renaissance architecture for their exteriors and interiors, communicating stability and substance. The bank was a serious, hushed, formal space where tellers stood behind counters and armed uniformed guards stood at the door. Then during the past several decades, banks had a generic personality, with a combination of ATMs on the outside and tellers at the counter, and managers in various types of consistently bland offices on the inside. You could be buying insurance or getting your taxes done if it were not for tellers exchanging your money. Banks went from authoritative to unimaginative, encouraging customers to use the ATM machines in the front and the drive-thrus in the back.

However, banks today—particularly regional banks—want to be seen as people friendly and accessible. Ray Davis, the president of Umpqua Bank in Portland, Oregon, recognized that he was actually in the retail business and so needed to sell his products in a way to make customers want to shop there. To rethink his bank strategy, he turned to an atypical source to redesign the employee and customer experience. Ziba Design, an international product design firm based in Portland, was asked to help rethink the brand experience to create a bank that could be viewed as a neighborhood partner and friend rather than a stand-off, undistinguished business.

A bit about Portland gives context to this collaboration. Both Umpqua and Ziba are part of the cutting-edge culture of Portland. Portland is also the home to Nike, a unique DIY culture, and a center for experimental cuisine. Portland food carts and restaurants are admired for their originality and experimentation, and trend researchers all over the world follow the culinary culture. The city is known for its cultural diversity and a commitment to outdoor activities and healthy living. The mayor rides a bicycle to work. Both Ziba and Umpqua are active participants and supporters of the Portland culture. It seems like an obvious choice, then, that Umpqua would seek out Ziba to design its new neighborhood banks, even though Ziba had not designed a retail or professional environment before. Ziba translated the idea of a trendy interactive neighborhood into a cultural experience that transformed how the employees worked and how customers saw and used their bank. This case study demonstrates that the traditional definitions of product, interface, and service are no longer valid in the product–service ecosystem.

The result is a bank that has received acclaim from both the banking industry and the design community (including a Gold IDEA Award from BusinessWeek and the IDSA), not to mention the customers. This case study demonstrates that successful design stems from the high-quality relationship between client and consultant. Ziba used the same approach in taking on this design challenge that it does when approaching any client opportunity. Using an ethnographic approach, it looked at both sides of the equation: how customers would like to see the bank operate and how employees currently worked and interacted with customers. The team created an experience that removed the barrier between customer and employee. To accomplish this, it changed the space of the interior and added support elements that enabled employees to more directly interact with customers and for customers to find the bank a place they wanted to visit.

Ziba created the look and feel of the bank to make it competitive with a high-end retail store, contemporary restaurant, or a coffeehouse (see Figure 8.3). It offered space for community events and even had featured local musicians through CDs and online services. The design elements in the space were contemporary and competitive with the trend-setting stores in the Portland area. The bank became an experience to savor, not a drive-thru. Umpqua offers free Wi-Fi and a lounge area, and even its own blend of coffee, for customers to stay for awhile or comfortably wait for services. Employees were repositioned in the space with new types of office furniture and equipment, to make it clear they were there to interact with customers. All the touch points for the bank, from the outside communication on the Web and in print, to the direct experience at the bank, were consistent, creating one unified brand.

Figure 8.3. Umpqua Bank.

(With permission of Ziba Design)

Envisioning the bank service as a retail product resulted in a new way to look at its traditional service. The result was success. When Umpqua opened its first “store” under this model, it generated record deposits: $1 million in the first week and $50 million over the first nine months. The bank then converted each of its branches to this new format.

UPS Moves Beyond the Package Delivery Industry

Since Jim Casey founded UPS in 1907 with just $100 in financing, the company has grown to be more than a $50 billion corporation today. What is often thought of as a package delivery company has transformed into a global service provider of information and logistics, financing, and delivery of goods. After going public, the company was named the 1999 Company of the Year by Forbes Magazine, which stated, “UPS used to be a trucking company with technology. Now it’s a technology company with trucks.”3

UPS has developed the most recognized brand in the package delivery business and is overall one of the most recognized brands today. Its shield, color brown, and drivers are core to the brand and, along with the vehicles and employee loyalty, have made UPS one of the most successful companies of the second half of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century. UPS has targeted and achieved attributes of reliability, trust, quality, and attention to detail. Customers send their packages around the world with confidence, knowing that they will arrive on time and intact.

UPS has a consistent identity system that graces a plethora of products, including packages, drop-off boxes, storefronts, interiors and counters, uniforms, trucks, containers, aircraft, and Web sites. The UPS shield was recently updated for a 3D global world. However, the shield itself goes back to the 1930s and, along with the color brown, communicates value to loyal customers.

UPS saw a POG in the evolving global economy. Companies spread across the globe required the ability to exchange goods quickly. UPS’s development of a global infrastructure allowed it to develop its own new business in global commerce. Today the company is in constant evolution as it anticipates the effects and needs of the global economy.

UPS has become an “enabler of global commerce.” Its goal is to play a role in the supply chain over the life cycle of a product, from the sourcing of raw materials through manufacturing of the product, to delivery of the product, and, finally, to after-market repair, replacement, and disposal of the product. To accomplish this vision, the company has broadened its focus to the movement and control of goods, information (that accompanies those goods), and funds that enable the transaction of the goods. UPS recognized that, in addition to an infrastructure to support the transport of goods, its infrastructure supported the transport of information. UPS spends more than $1 billion each year in the development and maintenance of information technology to support its services. Its package-tracking system rivals that of any competitor. UPS knows where a package is at any time and, through an electronic signature, when the package was delivered. UPS knows the buyer and seller, and possesses information about their shipping methods and product inventory. Knowledge is power—and in this case, this knowledge gives UPS the power to provide additional services to the customer. For example, financial transactions between buyer and seller are triggered after a package is delivered. The electronic delivery signature coupled with a growing financial arm to the company allows UPS to commence financial transactions between the buyer’s and seller’s banks.

UPS recognized that customers became stressed over the care of their packages and that they feared they might be late or, worse, lost. Given that the company had the ability to know exactly where a package was at any point in time, UPS saw the opportunity to offer the same information as a service to its customers: A customer can track a package as it travels around the country or the world. In reality a customer needs to know only that the package will arrive at the destination on time. However, this added service augments the VO attributes of security, confidence, and power of the customer, a no-cost service capability with deeply felt emotional returns.

UPS, then, has grown to be not only a package delivery service company, but an information company. By contributing to the production of a product and tracking that product over its life cycle, the company has successfully identified numerous POGs. For example, UPS might not own the ocean liner that transports the goods across the ocean, but it can control the information about the inventory on the ocean liner. UPS might also use its capital arm to fund the inventory and support the transactions with the inventory. It can also control the information that moves the goods across customs and then transport the goods from there. As another example, as the Internet created e-commerce, not only did UPS sense this POG early and establish itself as a core service to transport goods purchased over the Internet, but it also provides services to support the infrastructure to enable commerce over the Web.

To establish and maintain its reputation as an information company, UPS’s challenge has been to move the brand at the speed of the company while maintaining brand loyalty. The company wants customers to associate the brand with the attributes of speed, express delivery, innovation, technology, and global reach, in addition to the established attributes of reliability, trust, quality, and attention to detail. In this competitive industry, the company must constantly anticipate new challenges from the competition. For instance, UPS has been delivering overnight packages since 1954, but with the integration of overnight transportation into the speed of business in the 1990s, overnight delivery became a critical service and the new cost of doing business. As other companies got into the market, UPS took advantage of its infrastructure and evolving technical expertise to remain the leader in overnight delivery today, delivering more packages overnight than any competitor. The challenge is for the company to counteract advertising and branding messages from other companies, such as FedEx, and to maintain the consumer’s perception of possessing the speed and technology to be the best overnight delivery company.

Product companies and service companies overlap. This is certainly the case with UPS. The product that UPS produces is an increase in the speed at which companies can do business. UPS manufactures and processes deliveries; the manufacturing starts with accepting information in envelopes or packages (raw material) from one point and distributing it to another point. The process in between is a delivery factory/central processing unit that collects and redistributes information. It encodes from the pickup customer and decodes to the delivery customer with each package as if it were a byte of information. UPS measures its success by its percentage of on-time deliveries the way companies measure the manufacturing quality of their products. The UPS on-time delivery rate is the 6σ of the service industry. Behind the package that someone receives is an array of people and products that are required to deliver that package.

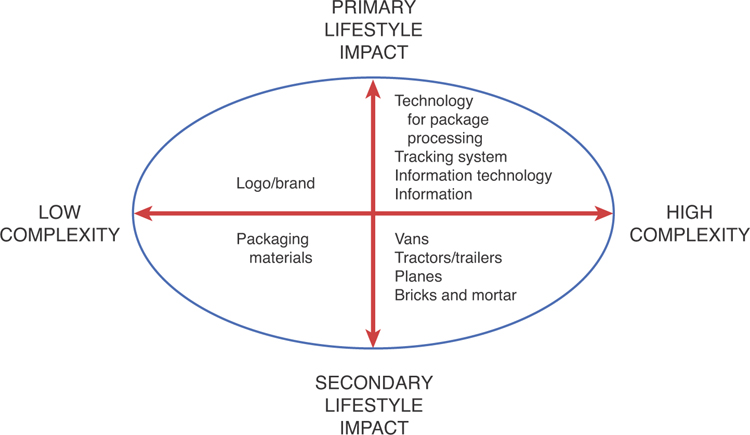

The PDM serves not only to understand where UPS must focus its effort, but also to see where the focus on information comes from. Figure 8.4 shows the PDM for UPS. In the lower left cell are the packaging materials used by customers, speced out by UPS but readily manufactured to order by many vendors. The lower right cell holds UPS’s 100,000 ground vehicles, each built to UPS specification, and the more than 200 planes and array of buildings that process the packages. The upper left cell includes the brand and logo design. The upper right cell, as always, shows critical components to UPS’s business. Located there are the technology to process the packages en route; the tracking system; the information technology to process tracking, delivery, and financial information; and the information itself. The information must be included there because it is the resource that allows UPS to deliver its services. Thus, it becomes clear that information is core to UPS’s growth, which explains why UPS has become an information company.

Figure 8.4. PDM for UPS.

UPS has extensive and ongoing user research. It takes three complementary paths: First is what it calls a Customer Satisfaction Index, an ongoing, in-depth analysis based on an extensive questionnaire sent to several thousand customers on a quarterly basis. Second is its Dialog Program, a constant (24/7) program in which customers are phoned and asked about one or two issues for feedback on their delivery. Finally, UPS uses small focus groups that target specific markets and geographic locations. It would be interesting to see how the ethnographic methods of Chapter 7, “Understanding the User’s Needs, Wants, and Desires,” might further benefit this successful company.

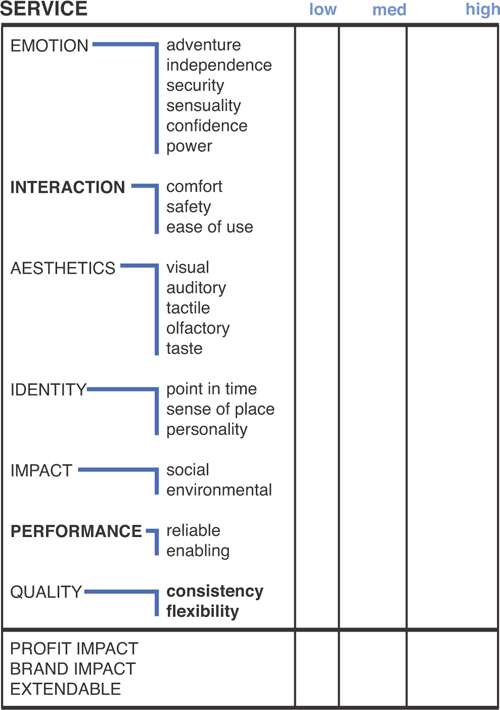

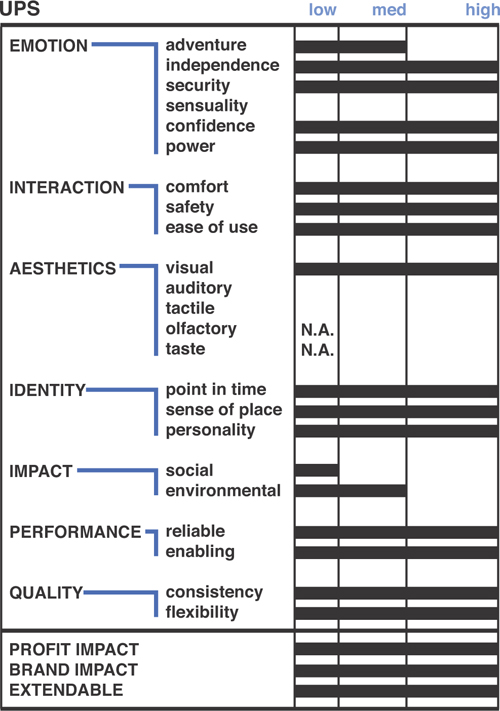

UPS is a company in the Upper Right. It clearly adds value and merges technological innovation with brand equity. The service VOA chart (see Figure 8.5) shows the service product high in the security, comfort, and power emotional VOs; the product interaction VOs; the visual aesthetic VO; the product identity VOs; and, of course, enabling and reliable performance, and consistency and flexibility VOs. The company also addresses environmental impact, as discussed shortly. The company addresses social impact to some extent by supporting communications across the globe, but UPS has an opportunity to develop this VO further. The only other non-high VO is adventure, which is still strong, in that people are not on an adventure, but their packages are, and they can follow the adventure online.

Figure 8.5. VOA of UPS.

With overnight delivery, domestic package delivery, and global delivery, UPS transports 5.5% of the U.S. GDP and 2% of the global GDP every day. Because of the vast resources needed to accomplish this, UPS recognizes its impact on the environment. The company instituted an approach for carbon-neutral shipping through carbon offsets, actively compensating for the obviously required carbon emissions to provide shipping today. It also instituted an eco-responsible packaging program to encourage the use of sustainable packaging materials.

Combining physical, technological, and human assets with a unified means of communication has allowed UPS to grow from a package-delivery company to a logistics company. As the company targets new areas and finds emerging competitors with different services, the package and information delivery service promises to be an exciting arena for growth in the twenty-first century.

The Disney Renaissance: The Ultimate Entertainment Service

Entertainment is another form of service. The industry is human intensive, with the movie, TV show, or amusement ride only the means to help deliver the otherwise intangible attributes of fun, escape, and fantasy. Clearly, the ultimate entertainment service is Disney. From the parks, to the shows, to the movies, the delivery is outstanding, with every touch point considered and designed to deliver the optimum experience.

However, Disney was not always the poster child and exemplar of the entertainment industry. After pioneering theatrical animation in 1937 with the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Disney animation was the undisputed leader throughout the Golden (1930–1940s) and Silver (1950s–1960s) Ages of animated film. However, Disney animated films began to decline in quality and success during the 1970s. A confluence of factors led to the 1980s being considered the darkest period in Disney’s history.

Although Disney continued to pioneer the use of new technologies, specifically CGI, the films were considered forgettable and the appeal was unidentifiable. In 1985, for example, The Black Cauldron was almost given a PG-13 rating, whereas, just one year later, The Great Mouse Detective was deemed too juvenile and had no adult appeal. Disney was operating without a cohesive vision for its movies. The result was minimal critical praise for its movies, with general disappointment in the box office between 1979 and 1988. And for the first time, Disney faced direct competition. Don Bluth, Disney’s lead animator, left in 1979 to start his own successful production company, Don Bluth Productions, which produced such hits as An American Tale and The Land Before Time.

However, by the late 1980s, changing SET Factors created a new POG for what would become known as the Disney Renaissance. This period, between 1989 and 1999, was one in which Walt Disney Animated Studios released a string of commercially successful and critically acclaimed animated films, including The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and The Lion King. Disney’s success through the Renaissance was the byproduct of an interdisciplinary collaboration between the team of Roy Disney leading animation, Jeffrey Katzenberg from business, and Michael Eisner at the helm, allowing and supporting Katzenberg’s quest. Linking a clear business strategy for higher profits with investment in traditional animation, leveraging new technological capabilities through computer-aided animation, and recognizing the potential of Broadway-like songs and lyrics created the SET Factor combination that responded to the need for a more sophisticated yet emotional product.

The stage was set for a resurgence of Disney with a population boom in its core audience. The rise of the Echo Boom, or the children of Baby Boomers, began in 1981. These Echo Boomers became young children by the late 1980s and early 1990s, providing a large target audience for animated films. Additionally, in 1987, the United States economy was hit by a recession that would last through the early 1990s. With a bad economy, American families often chose to go to the movies instead of taking weekend trips. As a result, from 1987 to 1989, the total domestic box office gross was increasing over the previous year across all films, including both live-action and animated films. Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, a non-Disney film, was released in 1988 to both critical acclaim and box office success. The film, which grossed $156 million in the U.S. release (compared to the $35 million typical for Disney films in the pre-Renaissance period), paid homage to the Golden Age of animation that reignited the public interest. At the same time, Broadway had released two massive hits, Les Misérables, in 1987, and The Phantom of the Opera, in 1988, showing the public’s excitement over the experience of musical productions. Bringing the musical to the animated screen with quality production and meaningful stories became the basis for the Disney Renaissance. Ironically, the successful screen later spawned new Broadway productions as well.

During the beginning of the Disney Renaissance, there was a technological change in the way animated films were created. After poor releases in the early 1980s, Disney invested in new production methods, working with Pixar Studios to develop the Computer Animated Production System (CAPS). CAPS was the first digital ink-and-paint system, and it revolutionized the way animated films were created. Also during this time, Disney began to outsource the noncreative areas of the animation process. By streamlining the production, Disney was able to release a movie every 18 months instead of every two or three years.

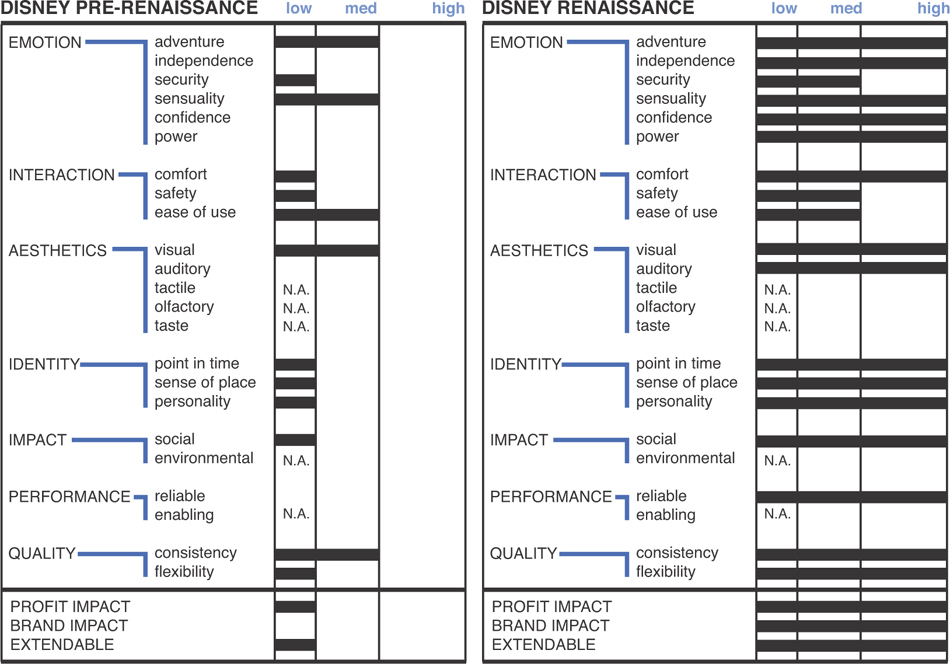

When comparing the Value Opportunity Analysis of Disney pre-Renaissance and Disney Renaissance, stark differences become apparent (see Figure 8.6). In the dark days of Disney, there was a lack of any real emotional connection to the films. Even the production aesthetics, consistency, and overall quality were limited. Until Ariel was introduced in The Little Mermaid, the first film of the Disney Renaissance in 1989, there had not been a Disney Princess, strong in ability to connect with audiences, since 1959. The lack of sensuality in the pre-Renaissance story and through the movie experience was indicative of the overall low value delivered to the viewing customer. The resulting lack of extendibility, the inability to merchandize or tie the films to the parks, further dampened the Disney brand and its revenues. In sum, the customer was cautious, without confidence or optimism about the Disney product.

Figure 8.6. The pre-Renaissance and Renaissance VOAs for Disney animated films.

Through the Renaissance, the value proposition changed. The strong adventure and sensuality (recall Sebastian the Crab crooning “you gotta kiss de girl” while Eric and Ariel were on the lagoon in the rowboat in The Little Mermaid) engendered an emotional connection to the characters. The films of the Disney Renaissance were musicals instead of the ill-fated action films, with songs written by Broadway veterans and scores that earned accolades and Academy Awards. Along with beautiful animation, the visual and auditory aesthetics were maximized. With the advent of CAPS, the visuals of the films were considered groundbreaking, and breathtaking. The technology was leading edge, and the quality was impeccable.

During the Renaissance, the films were showered with acclaim, garnering 24 Academy Award nominations and winning 11 Academy Awards. The average domestic box office gross of each film during the time was $142 million, with The Lion King grossing $312 million domestically in the U.S.

Disney has leveraged the success of its movies to build a cross-platform brand that consists of movies, theme parks, Broadway shows, soundtracks, merchandising, and more. The films of the Disney Renaissance have spawned best-selling and Grammy-winning soundtracks and songs. Additionally, Beauty and the Beast, The Lion King, The Little Mermaid, and Tarzan all became Broadway shows.

Disney theme parks bring Disney movies to life. Marketed as “The Happiest Place on Earth,” the parks are maintained to be in pristine condition every day. Successful films are turned into rides and other interactions that allow the user to experience the characters in the movies. In the reverse, many of Disney’s most popular rides have been turned into movies—for example, the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, so successful that the ride itself was then changed to accommodate the lead character, Captain Jack Sparrow. The experiential success of the parks has expanded to the Disney cruise line. This family-friendly cruise was designed to accommodate parents and their children, complete with costumed Disney characters—and unlike on other cruise lines, there is no casino.

Disney has also seen great success through original television programming and the development of the Disney Channel. Here Disney took its cross-platform model into television and radio. The television show Hannah Montana, which aired on the Disney Channel from 2006 to 2011, is a prime example. Along with creating a star out of the show’s protagonist played by Miley Cyrus, Disney was able to capitalize on the strength of its brand-building machine by releasing best-selling soundtracks, with songs featured on Radio Disney and two feature films based on the show.

Pixar, tightly interwoven with Disney’s recent success, is itself a story of Upper Right entertainment achievement. John Lasseter left Disney to head the creative arm of Pixar. Much Disney movie success in the 1990s and 2000s was a result of licensing Pixar films and then merging with Pixar itself in 2006. Lasseter returned to Disney as Chief Creative Officer. Upper Right products have evolved into Upper Right systems, with Disney/Pixar entertainment services, and the physical products that deliver those services, intertwined between different media and companies. It’s interesting to find that Steve Jobs, king of the Upper Right product, was in the middle of Disney’s more recent success through his purchase of Pixar, his negotiations, and the eventual merger of Pixar with Disney.

The tools and methods for the early stages of product design are the same as those used for interaction and service design.

Interaction Design

Interaction design broadly focuses on the interface between people and the product, adapting the product’s behavior to the needs, wants, and desires of the user. This might sound a lot like the broader discussion of product design throughout this book, and it is. The tools and methods for the early stages of product design are the same as those used for interaction design. However, according to Jodi Forlizzi, a leader in interaction design at Carnegie Mellon University’s Human Computer Institute and School of Design, interaction design is generally seen as technological interfaces between the human and the product; a product interface is the link between a user and a product that communicates how a product will be used and creates an experience for the people who will use it. Web sites and other digital interfaces, the means to command a technological machine (such as a robot), and the interface with an electronic instrument panel on a vehicle are all examples of interaction design. In terms of a robot, an extreme example, the robot interacts directly with the human, but its behavior can also indirectly interact with and impact the human. A robot is a product, just like a vehicle, or the BodyMedia FIT System, or the Frozen Concoction Maker. Although the design of the interface specifically focuses on the means of interaction, the larger task is to design the product and its way of interacting with people. Thus, the tools for uncovering opportunities and users’ needs, wants, and desires apply equally to the design of the interaction, its interface, and the design of the larger product.

Interaction design finds itself as part of the service design chapter. Interaction design, like product design, generally transcends all types of products that people interact with via technology. However, this is particularly critical for services in which interaction takes place via the Web or through another technology.

Consider the interaction designed in the BodyMedia FIT System. Although the user need not do anything except wear the device, when users want to access their data, they use the BodyMedia Web site, where data is automatically uploaded, analyzed, and put into a form that enables easy and consistent information to the user. The current use of Bluetooth technology makes this transfer of data seamless, and the attention to the Web interface makes interaction with the data inviting and cognitively clear.

As with any product, the SET Factors uncover the context of the product while the VOA models the value proposition of the interface for the user. The categories for the VOA attributes are again consistent, with the changes in terminology that align with service design working equally well with interaction design (see Figure 8.2): Instead of speaking about ergonomics, the category is better called interaction; quality, in this case, is not the manufacturing quality of craftsmanship and durability, but rather the consistency of the interface and its flexibility (and thus durability) over time. For example, the iPhone is an open system. The basic platform allows a consistency across screens and hand interactions. The platform is also flexible, with each user able to mass-customize it dynamically through different apps, home screens, backgrounds, and more. For the general service VOA, the term core technology was replaced with performance. For consistency, the term is also replaced for interaction design; however, interaction design tends to be based on technology interfaces, so core technology is also an appropriate term to use.

Interaction Through a Multisensory Interactive Teaching Tool

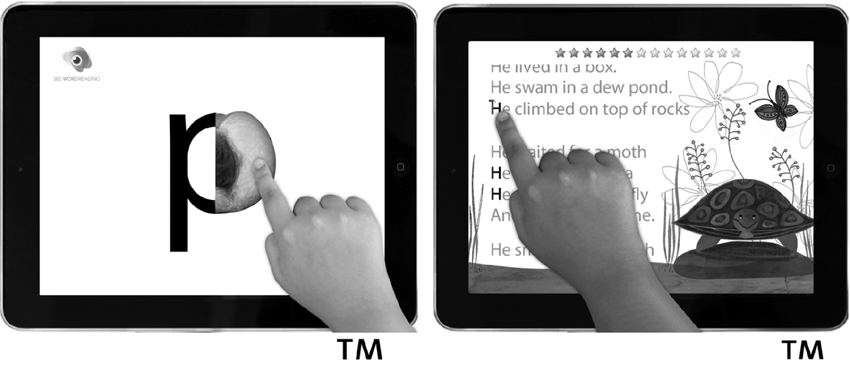

See Word is a new multisensory interactive teaching tool. It leverages the best attributes of an iPad with a highly creative interface that blends visual design concepts with learning theory to teach children how to recognize and pronounce letters. See Word was developed by Reneé Seward, an interaction design faculty member in the College of Design Architecture Art and Planning (DAAP) at the University of Cincinnati (U.C.), in collaboration with faculty in education at U.C.

Children learn in many different ways. The standard method of teaching children how to recognize and pronounce letters is through visual recognition and auditory sounds. Remembering the shape and the sound together usually results after several repetitive rounds, and then children can start to put the letters into words. That process is not the same for all children. Many children need multiple senses to embed letters into their memory as both shapes and sounds. If children fall behind in recognizing letters, they also fall behind in forming words and learning to read.

Computer programs existed that aided but do not free students from their support. Non-tech approaches used printed manuals and books without any dynamic interaction. Finally, contemporary visual teaching tools lacked a solid basis in learning theory. An opportunity existed for an Upper Right product that merged visual design with learning theory and supported the principles of hierarchy, legibility, and composition on a technology platform.

The concept Seward developed is a significant departure from the teacher-intensive methods, rote memorization, and software that already existed. This interactive tool (see Figure 8.7) can help teachers by providing a state-of-the-art design that allows children to become the center of their own learning. Teachers can spend more time on diagnosis and support, and less time on direct teaching. The use of an iPad supports the process by making students feel that they are using the latest product, not an assistive device. The interface is clear, designed to inspire children, and easy to master. The product records learning for teachers, to help them chart progress. Ben Meyer, also an interaction design faculty member, programmed the software that drives the system. The combination of Seward and Meyer allowed them to create the best connection between programming and interaction. Seward was also able to work with faculty in education, to ensure that all appropriate learning objectives were met. Through a testing phase working with teachers and students in Cincinnati schools, the interface showed promise as a new way to teach.

Figure 8.7. See Word.

(Courtesy of Reneé Seward)

The interdisciplinary development team worked with special education teachers and other teachers in the Cincinnati Public School system to test the concept. The testing process itself was codeveloped concurrently with the interface, helping to ensure greater accuracy in measuring the true learning that occurs. The team went through several rounds of qualitative feedback with early versions before developing the quantitative statistical methods that have provided the next level of proof of concept. It is often the case that early innovation suffers when a new group attempts to develop measures to verify claims without in-depth knowledge of the concept. Proper assessment is as important as the core innovation and is both an art and a science. It is important that evaluation processes be introduced early in the process, with a core development team working with researchers and statisticians to create relevant results. As the team shifts from qualitative to quantitative assessment, the knowledge learned in the early stage becomes the basis for the larger study. This is as true for education as it is for consumer products.

Summary Points

• Services use the same tools and methods as physical products to navigate the Fuzzy Front End.

• Most Upper Right products require intangible services, and services require physical products.

• An interface is the critical means of connecting products to services.

• The next level of breakthrough innovation leverages the product–service ecosystem.

References

1. www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2012.html

2. S. J. Sucher and S. E. McManus, The Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, Case 9-601-163 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School, 2005).

3. Barron, K., “Logistics in Brown,” Forbes Magazine, January 10, 2000.