Human resource management

2.1 The manpower plan – recruitment and termination

The aim of human resource management (HRM) is to meet the manpower needs of the company, now and in the future. To this end it must be effectively linked into the processes of recruitment and termination.

Manpower planning

The various stages of manpower planning are designed to ensure that the organization has manpower resources to meet the business needs in skills, number of employees and cost. It does this by:

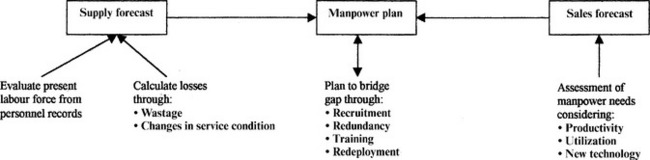

In order to do this, we start with the future business plan and break it down into the activities which will need to be carried out (Figure 2.1.1). These activities then need to be expressed in the skills required and the number of people possessing them.

We then have to evaluate the existing manpower in skills and numbers, calculate the expected losses and compare the resultant balance to that required by the business plan. We have to bear in mind any major organizational or technological changes expected both within and outside the organization.

Evaluate the existing workforce

Assuming that adequate personal records are available, it should be possible to draw up a profile of the existing workforce:

• Skills available: Each skill used within the organization needs identifying. This will include qualifications and experience of using the skill.

• Present training plan: This gives an idea of how present skill levels are changing.

• Number of staff: Linked to skills will be the number of staff having that skill, and how they are at present structured.

Levels: This relates to the structure within the organization, i.e. supervisors and managers.

• Age analysis: This is important and is tied to the above four factors.

Allowing for change

It is possible by analysing past and present records, coupled to any anticipated changes in conditions, to calculate what the probable changes in the present labour force over the planning period will be.

Stability

Any group of people joining an organization will stay varying lengths of time. Some will leave quickly, some will be promoted and the others will spend differing times with the organization, perhaps to retirement age or leaving due to health problems. It is common that a pattern is set up within a particular job role, which will repeat itself in the future unless a change is made.

We calculate the number of survivors over time by comparing the people at the start of a time period with those still there at the end of that period. We can then take the leavers during this period to find the average. This, combined with the age analysis, will enable us to make predictions about the numbers leaving by natural wastage during periods of change.

The figures on stability and turnover can also indicate where a change in HRM policy may be required. It is costly in management time in recruitment and training to be continually dealing with newcomers (see Section 2.2).

Changes in conditions of employment

In addition to leavers, changes in conditions of employment such as hours of work and holiday entitlement may alter the available working hours to meet the demand.

Some of these changes will be by negotiation with employee representatives. Some may be due to changes in the general labour market. Others may be dictated by government decree – national or EC such as the EC Directive on working hours.

Other internal changes

Factors such as the technology used and the organizational mode will effect numbers of staff required, skill requirements and even the levels of supervision and management needed.

The productivity and motivation of the employees can be affected by mode of management and/or linkage to their pay (see Section 2.3). This can also be factored into the equation.

External changes

In addition to government induced changes in conditions of employment, the external availability of labour is affected by:

• Social factors: For example, the attitude and aspirations of school leavers.

• Education: There has been a rapid growth in both further and higher education for school leavers.

• Changes in age dispersion in general population: In western society the life expectancy is increasing.

• Changes in migration within, and outwith, the country.

• General economic conditions, locally, nationally and internationally.

All of the above requires careful analysis to determine the potential of the existing staff resources and the labour market to meet the business plan requirements.

Where a gap has been identified between the existing labour force’s capacity and that required by the business plan, the manpower plan lays down how to bridge that gap. This will include recruitment, training, redeployment and perhaps redundancy.

Equal opportunity

At the manpower planning stage, it is useful to categorize employees by sex, ethnic origin and disability. This should include their level of authority, and will enable you to determine if there is under-representation of any of these group which may call for some positive action to redress this.

Finding the right person – recruitment

For an organization to be successful, it is important to have the right person in any job. The recruitment process is the entry point for all personnel, therefore this is the first opportunity to match what the organization requires in its people.

• The job will be carried out effectively in time, cost and quality.

• Training time will be short.

The negative reasons are:

• The job will be carried out ineffectively, increasing cost and time and reducing quality.

• Training will be long and perhaps ineffective.

• The employee will leave within a short period – voluntarily or otherwise:

• Other staff may be overworked to cope with one person’s shortcomings.

It is important therefore that the recruiting process be:

• Effective: Finds and selects the correct person.

• Efficient: Cost effective in staff time and advertising.

• Fair: To all potential candidates, especially in legal terms.

The process involves identifying the requirements, attracting suitable applicants and selecting the most suitable.

The job’s requirement

What is the job we need to fill?

We need to examine both the present duties and skills required and anticipate the changes that will likely occur within the near future. Consult the present job holder, colleagues, the supervisor and any specialists involved.

A vacancy may give an opportunity to revise that job and others within the section in line with new technology or processes.

Job description

This document is the basis of many processes within HRM. It needs to describe tasks and decisions made:

• Main purpose: A single sentence describing the job’s objective.

• Main and minor tasks: What is done, including method and equipment used including frequency.

• Scope of authority: Decisions made, and referred.

• Context: Who directly supervises, others reported to during work day and any subordinates.

• Working conditions: Physical, hours of work, shift pattern.

An example is shown in Figure 2.1.4.

Personal specification

From the job description, we can decide the characteristics of a person who would ideally fit the requirements of the job. As it is not always possible to get the ‘ideal’, we should also indicate the minimum acceptable, e.g. someone with some of the characteristics needed who may be fully trained and developed. We may also wish to attract people who have the potential to move to other positions within the organization.

We must ensure here that we do not introduce a bias against any particular section of the population by setting any unnecessary requirements. We may have to prove we are operating equal opportunity during recruitment.

There are two commonly used systems for drafting a personnel specification:

Alec Rodger’s Seven-point Plan:

• Physical make-up: Health, appearance, bearing, speech.

• Attainments: Education, qualifications, experience.

• Special aptitudes: Mechanical, dexterity, words and figures.

• Interests: Intellectual, practical, active, social, artistic.

• Disposition: Acceptability, influence, steadiness, dependability, self-reliance.

• Circumstances: Ability to work unsociable hours, travel, move location.

Munro Fraser’s Five-fold Grading System:

• Impact on others: Physical make-up, appearance, speech, manner.

• Acquired qualification: Education, training, experience.

• Innate abilities: Quick comprehension, aptitude for learning.

• Motivation: Goals, consistency, determination, successes.

• Adjustment: Emotional stability, stress handling, ability to get on with people.

Attracting a suitable candidate

We need to select the process that gives the best opportunity of reaching the target group of potential applicants:

• Internal: Often used for promotion, but can also be useful in developing present staff by widening their experience. It can also be useful to move a person into a job that better matches their skill and aptitude. You do have more pertinent information on candidates, but may be accused of favouritism. A point to note here is that being highly skilled at a particular task often has little relationship to an ability to perform satisfactorily in a given one – perhaps ignoring this has led to the Peter Principle that each employee will be promoted up to his level of incompetence.

• Word of mouth of existing employees: Good for strong group feeling amongst workforce but will probably exclude some sections of the local population.

• Local education, schools, colleges, universities and career centres.

– local newspapers, etc. – especially for lower skilled personnel

• Recruitment consultants – temporary, specialists and senior posts.

Any advertisement should be carefully designed to attract mostly those meeting the personnel specification. It is as inefficient to attract the overqualified as it is the underqualified.

Using application forms

Application forms are useful in providing in the same order all the information required to short list applicants. We should, however, use a different form for each type of job, only asking for the pertinent information against the personnel specification for ease of short listing. Unfortunately very few companies do so, which can put off potential candidates.

Selecting the best applicant

The initial stage is to prepare a short list from the applicants of those who appear to best meet the personnel specification. This reduces wasting both candidates’ and staff’s time and expenses. Where practicable reply to all applicants. You may want some applicants to reapply for other jobs later – if so, keep their particulars on files, and tell them what you have done.

Inviting for interview

Short listed personnel should be invited for an interview/test. The letter requesting attendance should explain to the candidates where and when to attend and also what they will be expected to be subjected to during their selection.

This selection process, unfortunately, is full of opportunities for errors. This is partially due to the methods employed, but also due to the artificial conditions where both sides attempt to match their needs, sometimes concealing the true situation.

Good selection has to be planned. Methods used include:

• Selection tests: Many jobs require skills which can be, and should be, tested to determine competence levels. These can include manual skills, writing and numeric skills, use of IT and even group working.

• Psychological: Although controversial, these are still often used to determine attitudes and mental reasoning by larger organizations.

• Interviewing: The most common technique, but especially prone to snap judgement. May be formal and/or informal. Methods are from interviewing on a one-to-one basis by several people to being interviewed by a panel.

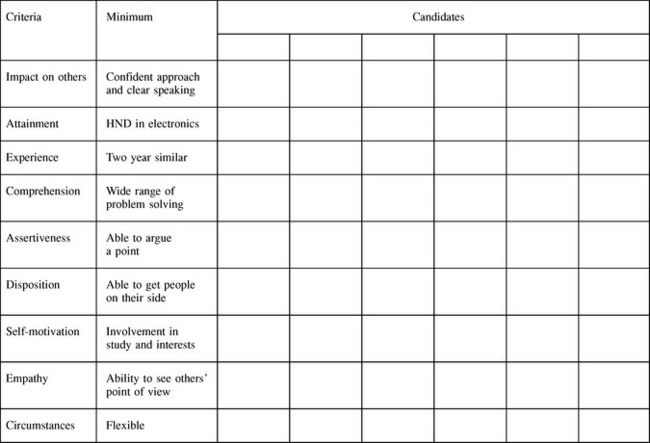

• It is common to have a form (see Figure 2.1.5) completed by everyone involved in the process to ensure all candidates are judged equally against the personnel specification criteria.

Bearing in mind time and cost, the more people who have connections with the post involved the better, to get a wide range of opinions. Make sure that they have received training in the selection process.

It is imperative that the direct supervisor is heavily involved for commitment.

Job offer

Bearing in mind the importance of this stage, it is necessary that the decision is made to match the job requirement. Everyone involved must accept the decision made.

Remember that the unsuccessful candidates will be disappointed, but you may still want to use them at a later date. Be courteous and inform them gently of your decision.

Make any job offer subject to receiving suitable references, but remember these may not convey the whole truth. They are best for factual information such as job title, length of service, attendance and duties, but a personal phone call may extract more useful background.

When making a job offer, always state any period of probation involved and the stages of review.

Contract of employment

The first legal step is taken here. Under the Trade Union Reform and Employment Rights (TURER) Act 1993, employees must have within eight weeks of starting work an express statement detailing:

The Employment Protection (Consolidated) Act (EPCA) 1978 states that employees must receive a wage slip detailing deductions made. It also confers rights against unfair dismissal after set time periods, which are adjusted from time to time by different governments.

Discrimination

At this stage make sure that you have covered yourself legally. The pertinent Acts are:

• Equal Pay Act 1970: Equal pay for work of equal value.

• Sex Discrimination Act 1975: No discrimination on grounds of sex or married status.

• Race Relations Act 1976: No discrimination on grounds of race, colour and nationality.

Under these acts, it is not illegal to take positive action to encourage applications from under-represented groups. It is illegal, however, to make positive discrimination during the selection process. There are exceptions but they must be ‘genuine occupational qualified’, i.e. actors, care assistants, social workers dealing with particular ethnic groups.

Under this act, you must justify any decision not to employ a disabled person and must make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to the workplace if this would aid the practical effects of the disability. Remember many disabled people do make excellent employees.

Much of the disparity in pay is not due to the rate for the job itself, but could be due to a restriction in entry to the higher paying jobs. Equal opportunity policies are not yet required by law but are recommended. The Equal Opportunity Commission (EOC) have produced a model policy which organizations are strongly recommended to mirror.

There are other areas, such as age, where some discrimination appears to take place, which are not at present covered by law. These are under discussion, but no legislation has emerged yet. Governments, however, are showing concern in these areas by requesting organizations to include discrimination practices such as ageism in their equal opportunity policies.

A body which has had some impact in employment matters is the European Court of Justice. The EC is increasingly determining employee rights under legislation such as the Social Chapter with its Working Time Directive and Freedom of Movement for Workers within the EC. (Note that work permits are required for non-EC nationals, which can be a long and difficult process to gain.)

Terminating employee contracts

Eventually all employees will leave the organization – either voluntarily or involuntarily. Sometimes this is because the employment contract has come to a natural end – retirement or the end of a fixed-period contract. Sometimes it will be prematurely terminated by the employee or the organization.

Whatever the reason, this process has to be managed to ensure both that the employee is treated correctly and the organization does not suffer.

Employee resignation

An organization has committed resources into selecting and then training and developing each employee. When an experienced employee leaves, this investment goes with them and must be re-incurred. It will take time and money to build up an equivalent competence level in a new employee – even when the selection process is efficient in finding a replacement.

In addition extra duties and responsibilities will probably have to be undertaken by the remaining staff. This can be difficult to do if staff numbers are tight – for example, in a small company, and may affect the efficient operation of a section.

It is important that the organization establishes why the employee leaves:

• The resignation may be due to factors unconnected with the job such as family member moving to another location, looking after children or old/sick relatives, returning to education, etc.

Examining these may lead to changes in conditions such as childcare provision, job sharing, flexible time keeping, etc. to retain highly competent staff.

• It may be a sign of problems in the job itself or the management of it. If so then it may require input to prevent, or reduce the impact of the problem.

• It may be due to favouritism or harassment by other employees or managers which may come under headings such as sexual, racialism or bullying.

• It may be a sign that the recruitment process has:

• There may have been a failure in the training process, especially when the job has changed and training needs have not been identified.

• It may be that the organization has failed to recognize and make provision for the aspirations of the leaver.

• It may be that the job has changed resulting in a mismatch between the holder and the new job requirements.

It can be difficult to establish the full reasons why an employee decides to resign, but careful questioning can prevent a costly repeat of a solvable problem. It will also limit the organization’s exposure to legal action at a later date under unfair dismissal, or discrimination.

Note that when an employee has been ‘requested’ to resign and does so, a court or tribunal may decide this was under duress and is in effect a dismissal. In addition a resignation gives the organization an opportunity to look again at its management of people and their tasks and could lead to improvements.

Natural ends of a contract of employment

Even where there is a natural end of contract, this requires management from both the employee point of view and the organization.

Retirement

Normal retirement comes with plenty of advance notice giving the opportunity for succession planning and re-equipping the retiree for the new phase of his life.

Some people will be looking forward to their retirement, but others will feel that it is the end of their usefulness. The latter will need careful counselling. The treatment of the retirees will be noted by the remaining personnel and may affect their commitment to the organization.

It may be that retirees will have an opportunity to assist in peak times, holidays or even maternity leave for a remaining member of staff. Some will welcome short period or part-time work afterwards within the organization. Their experience can often be useful.

Early retirement is also used for organizational and/or employee benefit:

• It can ease redundancy situations.

• It can reduce ‘log-jams’ in promotion.

• It enables staff to pursue other interests, or start up their own business.

The conditions attached to the pension scheme and any enhancement offered by the organization will be critical here.

End of a fixed period contract

Because of the growth of this type of contract, the managing of its completion is important. The reasons include:

• You will need the holder to:

– finish the work satisfactorily

– hand over correctly to remaining staff

– not take away important information such as customer details.

• You may require the leaver again in the future.

• Your actions will be noted by any others on the same type of contract.

It is no surprise that the construction and other cyclic industries such as ship-building, suffer from a deluge of industrial action towards the completion of contracts.

You should treat end-of-fixed-contract leavers in a similar manner to those leaving under redundancy. A court may even consider that because of the actual stay of an employee through renewal of short-term contracts this constitutes actual normal employment and the leaver is entitled to redundancy terms and conditions.

Dismissal

Dismissal comes about by action from the organization to unilaterally terminate the contract of employment.

It is another area where the law has introduced constraints upon organizations to ensure that all dismissals are fair. Employees have the right to periods of notice, written reasons for dismissal and not to be unfairly dismissed under the Employment Protection Act 1978. This right is normally tied to length of service which is set, and changed, by government.

A dismissal can be considered fair on the grounds of:

• Lack of capability: Case needs to be shown of the lack in:

– Skill or aptitude: Attitude may come under this heading. Should have been addressed at the recruitment stage, but mistakes can be made there. A gross shortage needs to be demonstrated that has not been remedied after repeated warnings and attempts at remedial action. Long periods of ignoring the shortfall by management will weaken the organization’s case.

– Qualifications: Simple misrepresentation is easy and may come under misconduct. Sometimes, however, the employment contract may require the holder to attain certain qualifications during service. A driver losing his licence would come under this heading.

– Ill-health: Providing the circumstances are such that frequent absence, or state of health, prevents the employee carrying out his duties. Alternative methods of carrying out the job and alternative posts need to have been considered.

• Misconduct: Very broad category, includes:

– disobedience of a reasonable instruction

– persistent absence or lateness

• Redundancy: Can be under two circumstances:

Note that redundancies also have to be discussed with the employee and there is an obligation to inform the Department of Industry.

What courts and tribunals look at in these cases are:

• What is reasonable in the circumstances?

• What procedure followed (not having suitable procedures is not a defence)

• Are all employees treated the same under the circumstances?

Awards may be financial compensation or an order to re-employ.

Where the behaviour of management contributes towards an employee leaving, the court may agree that there has been constructed dismissal. The employee may then have a case under unfair dismissal.

Redundancy

Although redundancy can be legally fair, is not usually due to the employees’ direct actions and needs to be treated carefully to minimize the effect on those leaving and those remaining.

It must be continually stressed that it is the job which is redundant and not the person as such. It can be fairly traumatic for an employee, after many years’ faithful service, to be coldly told that he/she is no longer required by the organization. Stress counselling will probably be required and assistance in finding new employment.

There is no legally recognized method of selecting those to be made redundant. It must be shown to be on a reasonable basis. The convention of last-in-first-out has no legal standing and often organizations make the choice on a different basis – such as skill, competence or absences to ensure they keep the employees they feel have most to contribute.

Often organizations employ means to encourage people to accept voluntary redundancy by increasing their entitlement or granting enhancement to retirement schemes. The non-replacement of leavers is another technique to allow natural wastage to reduce numbers.

Care should be taken that accepting volunteers does not result in some sections, or skills, undermanned and others with a surplus. Retraining and redeployment may need to be carried out to rebalance workloads.

Problems 2.1.1

(1) Why do you think some people stay longer than others in a job?

(2) How would you describe the ideal person to carry out your own tasks, using any of the plans.

(3) Look at the job adverts in local papers and professional journals. Why are some more attractive to you than others?

(4) Think about any interview you have experienced. How were you greeted, put at your ease and questioned?

(5) Think about your place of work or study. What practical problems are there in accessing and working for a person in a wheelchair?

(6) Why have you left any position?

(7) Under what conditions do you think both the employee and the employer will feel comfortable in being re-instated after a tribunal decision?

2.2 Making the most of people – work design, training and development

For any organization to be fully effective, it must make full use of the potential of its workforce. One route is motivation, which is a complex mixture, as this section demonstrates. Another is to train and develop the present employees to their maximum skill and potential.

The rise of scientific management

Previous to the rise of the human behaviour movement, management’s actions tended to reflect Theory ‘X’ of Douglas McGregor (1906–1964), that states that management saw workers as:

• By nature lazy and avoiding work if possible.

• Lacking ambition and disliking responsibility.

• Being self-centred and indifferent to organizational goals.

Much of the labour force were uneducated and in a different class structure, which reinforced this view.

With the rise of the industrial revolution, traditional skills were no longer in demand. For example, studies by Adam Smith, the eighteenth-century economist, into pin production demonstrated that the division of jobs into small, highly specialized areas gave rise to large increases in productivity. This division of labour gave an added advantage that selection and training could more easily be carried out because of the limited range of skills needed by the job holder.

In this climate, Fredrick W. Taylor’s (1856–1917) investigations at the Bethlehem Steel Company gave rise to the birth of scientific management. He proposed that:

• Work content (time) could be measured to determine a fair day’s work.

• Pay can be linked to this measurement.

• All work could be studied to develop better ways of carrying out tasks.

Although Taylor’s theories came under severe attack, this has partially been because of misapplication of his techniques by untrained, or even unscrupulous, practitioners. His ideas and method of enquiry have given birth to work study and much of modern management thinking and specialization’s – including HRM.

Henry Ford (1863–1947), amongst others, took these ideas further by developing the system of mass production. This again substantially improved output at that time, but led to severe deskilling coupled to close control of work pattern and rate of working.

Motivation theories

Managers, and others, have always been interested in ways of motivating (and sometimes manipulating) the people under them. If an organization can get its people involved, then hopefully they will be more productive, make fewer mistakes and stay with the firm. There has been an input into understanding what makes people function effectively. The driving force is:

The leading theories put forward are:

Incentive theory

Here it is assumed that given the correct rewards (or punishment), the employees will work harder. This lies behind the concept of performance related pay (see Section 2.3). The misapplication of work study has brought this into disrepute for hourly paid personnel but surprisingly perhaps it is still used for senior executives today.

This theory states that an individual will increase his/her effort in order to obtain a desired reward if:

Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) identified several layers of human needs:

| • Physical: | Air; food; water; warmth; sex; sleep. |

| • Security: | Safety; shelter; savings; no threats; familiarity. |

| • Social: | Human contact; belonging; affection; friendship. |

| • Esteem: | Self-respect; others’ respect; status; power. |

| • Self-actualization: | Fulfilment; realization of potential; doing and enjoying what one does best. |

| • Transcendence | Spirituality. |

Each layer is always in existence but one layer normally dominates an individual at any one time (see Figure 2.2.1). Changes in personal circumstances, such as losing a job, can change the dominating factor.

Satisfaction theories

Fredrick Herzberg (1923–) identified that in most situations there are environmental factors that will motivate, or demotivate a person. He termed them motivators and hygiene factors. The factors are:Motivators (satisfiers)

Hygiene factors (dissatisfiers)

The point he stresses is that should a motivator factor be considered present it will normally motivate a person; however, if it is seen as missing it will not necessarily demotivate that person. Similarly for the hygiene factor its presence, or perceived presence, demotivates but its absence will not produce motivation. Table 2.2.1 demonstrates this concept.

There is little evidence that satisfaction does in fact substantially increase productivity. It undoubtedly does, however, appear to reduce job related stress and absenteeism and leads to long service.

The motivators link in with the incentive theory, if they are identified as rewards which meet some of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Intrinsic theories

McGregor also offered an alternative Theory ‘Y’ to describe the average worker:

• People are not by nature passive or resistant to organizational needs. They become so through experience within an organization.

• People will exercise self-control to meet objectives to which they are committed.

• People can work towards group goals, if they agree with them.

• People can come to seek responsibility.

• People are able to contribute creatively to workplace problems.

This, if true, presents a challenge to management to capture this natural inclination and direct it towards organizational goals.

Human relations movement

Elton Mayo and his team carried out experiments initially to determine the effect of rest and other improvements in conditions on accidents, absenteeism and labour turnover. Later studies, – the Hawthorne Experiment – established that work groups, and modes of supervision, do significantly control the rate of output from a section. This happened both in positive and negative ways.

The problem is that man is a complex animal whose needs depend on his inborn nature, his upbringing and education and how he perceives his environment. Man is difficult to predict and cannot be generalized.

In addition, money is a general exchange good that can be given in return for the inconvenience of working and which can be exchanged for things needed. This ability of workers to accept money and use it to meet needs outside of the workplace clouds the whole area of motivation.

Job design

Early in the twentieth century, job design was all about work simplification and cost minimization under three criteria:

• Breaking the work down into simple separate elements – deskilling.

• Closely specifying the work to be done – no decision making.

• Closely controlling the work rate – often using machinery to pace actions.

This meant that jobs became extremely limited and did not require the employee to make good use of their abilities. This resulted in alienation of much of the workforce from the goals of the organization. One manifestation of alienation is absenteeism, another is a tendency for industrial action to take place.

As more evidence became available, some organizations realized that changes in the working environment could lead to improvements in quality and output and reduce many of the negative incidents.

• Job rotation – moving operators around the simple tasks over the working period.

• Job enlargement – increasing the number of simple tasks done by an operative.

These did have some success in alleviating boredom, but still did not make full use of the employee’s potential. Efforts since have moved onto:

• Job enrichment – both widening tasks done and increasing decision making and creativity.

• Self-directed teams – giving a group substantial control over the tasks, including administrative tasks such as planning and communication with other groups, in effect doing their own supervision.

BPR, like work study, has had some success and some failure. The probability is that the failures have been caused by mishandling in implementation or resistance from corporate, or workforce, culture.

Improving employees – training and development

Assuming we have the right people working on correctly designed jobs, we have to ensure the holders receive sufficient and effective training to carry them out.

There has been continual, but unfortunately continually changing, government interest in vocational training. This started back in 1964 with the formation of Industrial Training Boards through to the Training and Enterprise Councils (TEC) in the 1990s and the introduction of work-based NVQs.

In 1991, the Investor in People (IIP) initiative was launched based on the need to maintain and increase the UK’s competitive position in world markets.

The Investor in People initiative is interesting not only because of its high aims but also because of its tie-in of training and development to the business plan of the organization.

This is where we will start – the business needs.

Identifying training needs

The events that trigger training needs include:

• New technology, e.g. change from electromechanical design to microprocessor control.

• A change in working methods.

• Increased flexibility – multi-skilling.

• Promotion or transfer to another post.

• Improvement of skills, e.g. to reduce quality problems.

• Changes in structure, e.g. a move towards self-managing groups.

Care is required that the identified need can be addressed by training and does not reflect some organizational or equipment problem.

Once we identify the actual need we need to break it down into what we are trying to install. The types of skills are:

• Cognitive skill: Basically thinking process – making decisions, analysing faults.

• Perceptual skill: Seeing and interpreting what we see – e.g. scanning an aircraft’s control panel.

• Motor skill: Controlling human physical movement; co-ordination of limbs with senses such as sight and hearing often have to be made.

Many jobs require a blend of each of these which is built up by training and requires continual practice to maintain at peak performance. Ability in training terms is the level of competence in using a skill.

People do have varying degrees of ability in the different skills. Some do appear innate, such as colour discrimination and spacial awareness. Most, however, can be developed, but not necessarily to the same degree in everyone. For example, not everyone has the inherent ability to develop to a world class athlete, but everyone’s performance can be improved. Abilities are often transferable between jobs.

Where the required ability is difficult to develop, then the selection processes must identify those who will struggle to attain them.

People also require core knowledge to be able to use skills effectively by having a background against which they can compare what is happening. Knowledge required includes:

• Basic knowledge, which a trainee is expected to have before training commences.

• Background knowledge about the company – especially so when inducting a new employee.

• Knowledge specific to the job: Reporting relationships, procedures, equipment, materials, fault recognition and diagnosis, etc.

We need to determine the blend of knowledge, skill and competence required to carry out the job. In other words we again have to carry out a job analysis – this time looking at these aspects (see Figure 2.2.2).

This information will come from a blend of observation and questioning of employees, supervisors and sometimes suppliers (in the case of new equipment or computer programmers).

It is the task then of how to install and develop this blend of knowledge, skills and attitudes.

Designing training programmes

Approaches to operative and administration training:

• Learning-by-doing (sitting with Nellie): Often just informal by sitting with an experienced operator and observing and then copying. Can be effective for low skilled tasks or where the experienced operator is a trained instructor.

• On-the-job: Very common. Normally done by experienced operator/instructor or the supervisor of the post. Mainly on a one-to-one basis but can be used for small groups.

• Off-the-job: Enables trainee to be introduced to new concepts and theoretical information. Can suffer if relevance to job not seen.

Methods of training:

• Passive – lecture/demonstration: Passing of information from instructor. Useful for blocks of new information.

• Active: Basically a learning-by-doing situation.

• Workshops to discuss and develop skills.

• Case study to analyse situations and approaches.

• Simulation to practise skills and interpretations.

Remember that learning is an inductive process – people need time to assimilate what they are learning. At the beginning they will require a lot of guidance, so that they know what to do and this reduces the trial-and-error sequence.

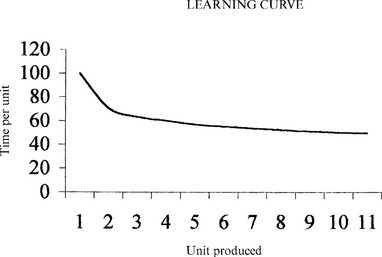

Feedback during the learning process is critical to attain a skill, knowledge or attitude. Constant repetition is required to attain full mastery as most tasks move through the learning curve (see Figure 2.2.3)

The induction of a new employee into an organization is normally a case of too much information too soon. This should initially be limited to the bare essentials of what they need right away with small feeder doses over the next few weeks – even using packages of information to read.

Developing people

People need developing in many ways rather than through pure training. Many of the abilities can be shown but they need to be assimilated in the trainee’s own way – especially in the field of management.

The development process can arise in two ways:

Kolb’s Model of Learning (Organizational Psychology, 1984) demonstrates that a four-stage iterative experiential cycle is required for full learning:

(a) Concrete experience: Describe what is happening.

(b) Reflective observation: Think about what cause-and-effect relationships are involved.

(c) Abstract conceptualization: Think what other relationships could be applied which may change what is happening.

(d) Active experimentation: Try out these other factors. Return to (a).

There is a variety of methods using a similar process to Kolb’s cycle.

NVQs. A National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) is built around participants building up a dossier, or portfolio to demonstrate that they not only can perform competently various tasks in a range of situations, but that they understand the reasoning behind the actions taken. The standards for the competencies have been set by lead bodies made up from industry and trade unions.

Shadowing: Basically involves following round an experienced employee to observe how he does his tasks. If the trainee has been training experientially learning can be effective. Often not structured enough to give more than a flavour.

Mentoring: Here a senior experienced manager, who is not usually the direct supervisor, takes charge of the training and development. The mentor acts as an adviser and protector to the trainee. The trainee has the mentor to discuss what is happening and different ways he can tackle them.

Coaching: Normally carried out by the direct supervisor. Similar to a football, or athletics coach, who takes a competent person and improves their performance by constructive critical comment and guidance. Regular feedback must take place for effectiveness.

Action learning: A similar concept to mentoring, except this time the mentor’s role is undertaken by a group of the trainee’s peers. Basically applies Kolb’s cycle. Being used significantly in post-graduate management studies and amongst self-development groups.

Evaluating the training

All training costs money and time. It should therefore be evaluated against its aims of meeting the organizational and the individual needs. The evaluation should also check actual costs involved and benefits received.

Records should be kept of what training staff have received and the levels of skills attained. These should be periodically updated to reflect the present competence level.

Methods of evaluating the training method include:

• Questionnaires: Immediate feedback from trainees – this evaluates the course more than the learning.

• Tests: Common on certificate courses. Can be used to test skills and knowledge competence. Can take the form of practical work such as a welding test.

• Pre- and post-questionnaires: To determine difference in knowledge. The post-questioning can be taken some time afterwards to show retention.

• Post-training appraisal: Of the trainee by his supervisor after training.

Problems 2.2.1

(1) Do you agree with McGregor’s Theory ‘X’ description of the average worker?

(2) What has personally motivated, or demotivated, you recently?

(3) How would you reorganize the tasks in a McDonald’s restaurant?

(4) Why does training receive a low priority in many organizations?

(5) Think about a child learning to walk. How long does it take before he/she becomes fully competent?

(6) Do you think constant practice alone is sufficient to enable you to master any task?

(7) Try to apply Kolb’s cycle to an activity which has been giving you some problems in getting to grips with.

2.3 Rewarding employees – pay and benefits

Salary, especially when compared to others’ within the same organization, can be a source of discontentment as Herzberg stated (see p. 75). People often use salary, and other benefits, as an indication to their relative status within the organization.

This section examines different methods of payment and other benefits in use.

Objectives of a payment scheme

It is important that organizations design an effective payment system to avoid discontentment among staff. Such a system would have as its objectives:External compatibility. Salaries and benefits should compare to the pertinent job market to attract new recruits and prevent losing existing staff:

Internal equity. Staff should recognize the fairness of:

Easily administered. To reduce cost and ensure the system is error free.Easily understood. People should understand why their job is a certain grade and why the salary for that grade is what it is.Management controls. To ensure the best use of money spent on salaries, there needs to be means of analysing and controlling the wage bill on basis of:

• Trends in numbers and various payment.

• Controllability through standards and budgets.

• Predictability over the short term.

• Preventing drifting of earnings irrespective of output.

Participative. If the employees themselves are involved in the design, not only will their knowledge and judgement be involved, but it will probably be more acceptable.

There are a variety of payment schemes which can be used alone or in combinations to match the needs of the organization and the employees.

Payment schemes

This is simply a set payment per hour, which is multiplied by the number of hours worked to reach due wage. There may be premiums for unsociable hours, overtime and even certain poor working conditions.

This is easily understood and aside from the differential issue seldom results in disputes.

However, productivity is not usually measured and hence it is difficult to control, except by budgets and close management. There is no direct incentive to improve output or reduce inputs.

Payment by results (PBR)

This is an effort to relate output/input usage directly to pay, which started formally following Taylor’s work. It is best used where personal performance greatly influences the output results.

Performance can be used to judge the effectiveness of a group of individuals, such as a section or a department. Where used for payment to large groups, a direct relationship between individual effort and pay can be difficult to discern. This overall performance could be used for a group bonus for supporting staff who are not on measured work.

The relationship between performance and pay can be geared to increase incentive or reduce reward where varying conditions can affect output performance as in Figure 2.3.2.

PBR is expensive to install but initial gains in productivity to the organization can be considerable. However, it must be well maintained to hold accuracy of times set and prevent drift through ongoing improvements by the operator.

PBR often results in friction between different workers when work is allocated due to perceived differences in ease of attaining targets. This can be especially so when the process itself is highly automated and gives little opportunity for the operator to affect output – except in ensuring the unit is constantly working.

PBR schemes will suffer credibility if management try to change targets without justifiable reasons – such as a new method.

By far the main problems arise during periods of fluctuation in work load which could affect time on PBR, and hence earnings. This arises from the frames of reference used by workers being different from that of management:

• Workers’ view: Over a period of time, they get used to receiving a set income under a bonus scheme. It becomes their norm. If for a reason beyond the operators’ control, their performance drops, then their wage is decreased from this norm.

• Management view: Basic wage is the norm. Bonus payment under PBR is always an extra reward because of harder working. If for a reason beyond the operators’ control, their performance drops, then they have not earned the portion of their wage related to performance. Pay then moves towards the management norm.

Therefore we have a failure of minds meeting. This failure in common thinking makes it easy for disputes to arise.

A linked problem is how to pay personnel who contribute towards individuals on PBR indirectly such as material handlers, inspectors and even their supervisors. It is common practice to introduce a payment linked to the bonus received by PBR workers. This often does not go down well with those whose have to expend extra effort to ‘earn’ their pay.

In addition to the normal measured PBR, there are other schemes which relate payment to performance:

• Sales commission: These are not based on the same detailed measurement of the work involved and are often based on contribution analysis coupled to personal opinion. Few details are available on their make-up and effect.

• Management-by-target meeting: Some staff, mainly managerial, have pay directly linked to measurable output or to attaining set objectives. Again few details are available on their effectiveness.

Measured day work

Because of the difficulty with PBR, and increased automation, many organizations have introduced this hybrid between time rate and PBR.

In this system the work content is still measured and targets set, but short-term changes in individuals’ performance has no immediate effect on their wage. Some control is still obtained, and attitudes to changes tend to be more flexible. The employee cannot directly influence his wage by varying work rate.

However, in the short term, this tends to be more expensive than PBR because lower performance (whatever the reason) is not reflected in a drop in labour cost. Remedial action becomes a question of negotiation.

Plant and company schemes

These range from profit sharing to a value-added basis and increasingly through share options. These can catch employee interest because it reinforces the message ‘we are all in the same boat’.

• Often payments are small in relation to the main payment received.

• Because the efforts of many get amalgamated, the more contributing and harder working end up with the same benefit as less performing ones.

• Because of the large time gap between an individual’s specific input and payment the relationship to individual performance is muted.

• Payments can vary substantially, as much of the results are determined by market forces.

• Organizations’ fortunes depend on decisions contributed to by only a few people – the top management.

• It is especially difficult to operate in adverse trading conditions where complex, uncontrollable external forces exist – often the time when employees have to work extremely hard and monetary rewards are low.

Merit rating

This is a differential time-rate payment made to workers on the basis of certain attributes or skills. It often results in suspicion of favouritism. Considerable variation can occur between sections in a large organization. Over time there is a tendency for everyone to rise towards the higher grades.

Appraisal related pay

More specific and open than merit rating, although it does share many features. Specially useful where individuals can be set targets and judged on their achievements. The award can be an extra percentage or a step up within grading. Differs from merit pay as the criteria are more explicit (see Figure 2.3.3) but scheme can suffer from similar suspicion and problems.

Figure 2.3.3 Factors under appraisal related pay and associated range of points against performance criteria (suggested by ACAS)

Performance distributions, e.g. a typical proportioning which can be used for setting payment differentials, are:

| Exceptional | 5% of staff paid + 10% |

| Highly effective | 15% of staff paid + 7.5% |

| Effective | 60% of staff paid + 5% |

| Less than effective | 18% of staff paid + 2.5% |

| Unacceptable | 2% of staff paid + 0% |

Benefits

There are three types of pension schemes.

State

There are two schemes administered by the UK government:

• Basic pension: This is contributed to and paid out from National Insurance contributions. It entitles all citizens to a basic pension. In recent years this basic state pension has been effectively reduced in comparison to the national average wage by successive governments.

• State Earnings Related Pension Scheme (SERPS) was an additional payment related to wage which built up credits towards additional pension. It has been phased out.

Government pensions are funded out of present government income. The growth of people being entitled to the basic pension though increased life expectancy has made government increased pressure towards company and private schemes.

Company and industry schemes

There has always been advantages to both organizations and their employees from company pension schemes:

• Helps to recruit and retain employees.

• Improves industrial relations.

• Gives a mechanism for early retirement as part of redundancies or long-term sickness.

Pension schemes vary considerably but normal provisions are:

• Condition of service for all staff.

• Employee contribution based on salary.

• Employee contributions may be ‘topped-up’ to increase entitlement.

• Employer matches employee’s contribution.

• Contributions go into a separately managed fund.

• Pension is made based on final salary and years of service, although some schemes work on average salary.

Although men and women must have equal access to company schemes, different retirement ages and survivor payments are allowed.

The government is keen that all employees become members of company schemes as they are self-financing and reduce dependence on the basic state scheme and back-up of social security payment.

Sick pay

As with pensions, sick pay is a mixture of state and employer funded.

Statutory maternity pay (SMP)

An employee who is pregnant is entitled to Statutory Maternity Pay. This is for a period of 18 weeks, 90% for the first six weeks and 30% for the remaining 12 weeks. These periods and payments may be extended in the near future. There are also rights for unpaid leave for family reasons for both mothers and fathers. This may become paid leave within the next few years.

Payment made is mainly recoverable from the Department of Social Security (DSS). Many companies pay in excess of the minimum, but this extra is not recoverable.

In addition the employee has the right to return to work for a period of twenty-six weeks from the date of birth, and again this may be lengthened.

Statutory sick pay (SSP)

Administered by the organization, the employer pays out a set payment when the employee is off due to illness. This is later reclaimed from the state. This is built up from:

• Waiting days – these are normally three days unpaid, but are linked to any absence over the previous eight weeks.

• Certification. A doctor’s certificate is required for over seven days, but for less than this the employee provides self-certification.

These payments can be transferred to the Department of Social Security (DSS) after twenty-eight weeks.

Company schemes

These can vary from the basic SSP to non-contributing schemes.

These schemes normally have a qualifying period of service and pay out full pay for a limited period followed by a reduced payment.

Absence and sick pay monitoring

Like any other benefits, this can be open to abuse by some employees. Most employees record low absences with small periods off. Others consider the scheme to be a right to take additional leave periods.

Careful monitoring is required – again bearing in mind equality and fairness in treatment.

Other benefits

There is a large range of extra benefits which organizations can offer their staff:

• Reduced or non-contribution to pension schemes.

• Company car, or mileage, allowance.

Initially these benefits arose as a cheaper alternative to making payment directly to staff, therefore gaining an advantage through group schemes and a reduction in personal taxation. However, the tax authorities are gradually catching up demanding that tax be paid on the value of the benefit received.

Some benefits are from time to time actively encouraged by government, although sometimes different government regulations appear to contradict this encouragement.

Job evaluation schemes

It is very unusual for everyone in an organization to be paid the same wage. This is understandably so, as different jobs require different skills and have different responsibilities.

How does an organization decide on the ‘rate for the job’?

The first way is to look at what the market pays and set the organization’s rate around that. However, two factors cause problems here:

• Local factors can often distort the rate for a particular job.

• Similar names can be used for substantially different jobs.

Therefore if these rates are used they may be out of line with others in the organization, which can cause feelings of unfairness.

Another way is to look internally at job rates – at least that is what the present employees are used to. This will result perhaps in a large number of different rates, which will need consolidating to around four or five rates.

Reducing the number of job rates

If we take all the existing job rates, rank them numerically and then draw a scatter diagram (see Figure 2.3.4), we should find:

• There is a considerable range.

• There is a pattern – a trend upwards as the rates are pre-ranked.

If we carry out an exercise on this information (see Figure 2.3.5) we find:

• There are four natural groups.

• Two job rates do not fall into a particular group. These were found to contain a pay element for supervision for leading a small team.

• If we take an average for each group, this can enable us to select a simple representative rate for that group.

• When we compare the actual rate to that selected value, some rates are higher and some lower. Therefore if we paid at the selected rate, there would be gainers and losers (see page 96 for benefits and problems in job evaluation).

• When looking at the sex in each group, we find in the lower rate groups, it is predominately female and the reverse in the higher groups. This will need investigating to discover the reason – is it due to real differences in value, or does it indicate a lack of either equal pay for equal work or equal opportunity in selection processes? This needs investigating.

The basic remaining questions to be answered are:

• Is the rate a good indication of the value of the job to the organization?

• Are the jobs on similar rates, close enough in characteristics to be classified as having the same value?

If the answer to the latter two questions is yes, then it would be possible to change into a reduced number of job rates.

However, changing technology and processes can often change the original basis for differentials. We therefore need a method that can fairly differentiate between jobs, which is capable of slotting new jobs into, or revising the rate for a changed job.

It must be stressed here that we are looking at the characteristics only of the job, not at how the present job holder performs in it.

Simple comparative methods

Job ranking

This is a simple method – often sufficient for a small organization. It basically means making a list of jobs in order of pay worth to the organization. It follows a simple procedure:

• Make a list of all jobs within the organization – without details of their pay rate.

• Go through that list and rank the jobs in order of the perceived importance to the operation of the organization – remember to look at the job, not how the person in it is performing.

• Compare this to the jobs ranked by pay – can give an opportunity to reduce the number of rates.

You now have a ranked list – any new jobs can be slotted into this list by examination. Similarly any changes in the job which change its importance can be refitted in.

Paired comparison

The paired comparison method is another simple method. It eases decisions by comparing every job with every other one – one at a time. This can mean a considerable number of comparisons have to be made.

• The basic procedure is to draw up a simple table with jobs heading each row and each column.

• You then move along the row comparing the row job against the column job.

• Award (place in intersection box):

• Once all jobs have been compared, total the values in each row.

• Check the total of all the jobs’ values by comparing it to the multiple of (jobs × (jobs – 1)).

The final run of a paired comparison is shown in Figure 2.3.6. The highest score was gained by the maintenance technician – the lowest by the janitor.

Job classification

This involves selecting one particular job description to be representative of all other jobs in its grade. A job is then compared with each of these prime examples to denote which it is nearest to.

Examples of this are shown in Figure 2.3.7.

Factor assessment

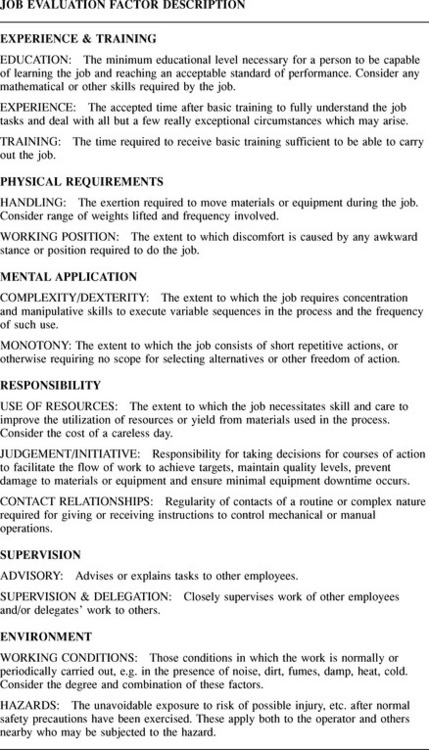

This widely used scheme attempts to value manual and clerical jobs through their characteristics, termed factors. The scheme normally uses four to five main factor headings, each of which can be broken down into several sub-factors. The International Labour Organization list over thirty commonly used factors.

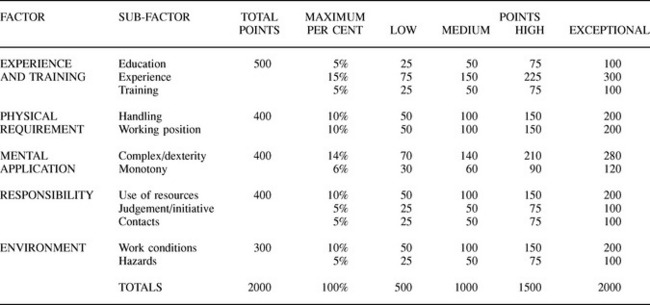

An example of the factor descriptions in a particular manual scheme is shown in Figure 2.3.8. The five main factors have been broken down into a total of 12 sub-factors. The descriptions should be simple and avoid ambiguity.

Figure 2.3.8 Job evaluation factor descriptions. (The comments under each factor must be clear, measurable and supportable)

The next stage is to decide for your particular organization which factor should contribute most towards people’s pay. This is highly subjective and can differ between quite similar organizations. The object is to achieve weightings which are understandable and fair to most staff in the organization.

The main factor weighting is then distributed across its sub-factors. Each sub-factor is then subdivided into 3–5 degrees normally with equal steps as in Figure 2.3.9. Note the points figure for a degree is indicative – actual points awarded can be between the values stated.

The reason for having a total number of points available as high as the 2000 shown here is simple. Even a low scoring job will end up with a healthy looking number, hence protecting people’s pride.

Jobs have to have a detailed description using the same factors as the scheme before they can be evaluated. This requires training in the technique. Similarly the evaluation is best carried out by an experienced team to prevent bias creeping in.

The designed scheme must be tested against key jobs to ensure that the corresponding totals correlate to these job’s rankings. Only after this could the breakpoints between job grades be decided on.

You will find that the grade for some jobs has changed – up or down. When a job rate has reduced, it is common practice to protect that person’s salary for a set period – up to three years. During this period, the organization should attempt to find another post paying a similar rate to what the employee was receiving.

It also must be tested for any bias against any group of employees, such as women.

Management

There has been some attempts at evaluating executive positions but these have not been developed to a satisfactory conclusion because of the lack of standardization of roles and the relatively fewer posts involved.

These posts tend to remain outside formal job evaluation schemes and salaries relate more to numbers of staff and turnover.

Problems 2.3.1

(1) What do you think is a fair basis on which to pay for different jobs?

(2) If an operative is paid £6.00 per hour for first 37.5 hours with time + half for overtime and works 48 hours what is his pay before deductions?

(3) Should operators be paid the bonus rate for their full attendance time, or just the time on bonus work?

(4) Which payment scheme would you personally prefer to be paid by? Why?

(5) What percentage of final earnings do you think is fair to pay as a combined state and private pension?

(6) Do you think continual ill health is a fair reason for dismissing an employee?

(7) What should you do if, following job evaluation, the rate for a particular job involving a large number of staff comes out with a substantial increase?

Appendix

Any organization depends on producing a profit to survive. Profit is basically the difference between the money earned and the money spent by the organization. Productivity is how well the organization makes use of its resources, be it people, machines or material to produce a high profit.

Basic work content of an operation

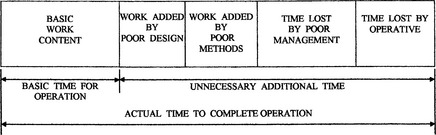

Most operation times are extended due to bad engineering or management. Figure 2.3.10 gives an impression of the effect of different factors in determining the actual time taken to carry out an operation.

The basic work content is decided by the function of the part and is the minimum (ideal) required to produce that function. The additional factors increasing the time taken from this basic time up until that actually used are caused by:Work content added by poor design

• Designer selects material which is difficult to process.

• Designer often selects process, which may not be ideal.

• Design produces variety instead of standardizing hence adding to non-value adding work.

• Designer sets tolerances higher than function requires causing extra processing.

• Designer selects larger starting size than necessary causing extra processing to reduce bulk.

Work added by poor methods

• Wrong process selected by designer.

• Wrong machine selected by production engineering.

• Wrong tooling selected by operator or production engineering.

• Poor plant layout causing unnecessary material movement.

• Process instructions wrong leading to extra reworking.

Time lost by poor management

• Excessive variety of products leading to extra non-value adding work.

• Lack of standardization leading to extra non-value adding work.

• Many design changes leading to tool breakdowns and quality problems.

• Poor scheduling where similar work is not scheduled together.

• Poor operational control extending process time.

• Lack of raw materials leading to idle time.

• Plant maintained poorly leading to extended process time.

• Poor working conditions leading to lost time through extra rest periods.

• Poor safety precautions leading to lost time through accidents.

• Poor training leading to inefficient operations and quality problems.

Time lost by operative

There are a multitude of techniques which management use to reduce the actual time taken towards the basic required. They all rely on recording and measuring what is happening now, developing better methods of working and then controlling to the new standards produced.

Work study

Work study is the systematic examination of all aspects of the working operation. Although it has been in formal use for almost a century, its application has often been poor and has led to it having negative images.

The modern ‘in’ technique in management cost reduction – re-engineering – basically uses a similar technique. Work Study is useful because of its systematic approach to identifying what is happening and then developing improvements.

Method study

The starting point for any change should be to examine and improve on what is presently happening – even before actually measuring the time taken. In order of preference the basic objective for each task examined is to:

The stages of method study are to select the operation to be studied on basis of perceived importance:

Record present operations using:

These should include exact distances moved and the time taken but this is not normally necessary the first time, as movement tends to be the easiest task to alter.

The important tasks are the OPERATION and INSPECTION where a material has work done to it or the material is counted or examined.

Examine the present method, asking the following questions, and then ask ‘WHY?’ to each answer received to the question:

| • What is happening? | WHY? |

| • Where is it happening? | WHY? |

| • Who/what is doing it? | WHY? |

| • How is it being done? | WHY? |

| • What is the required specification? | WHY? |

| • What are the required standards? | WHY? |

Develop a better method by understanding and critically examining the WHYs collected. Follow the ‘WHY?’ by ‘WHAT ELSE COULD BE DONE?’ until ‘WHAT SHOULD BE DONE?’ is arrived at.

Common examples are moving operations in the sequence that they are done so that the operative is carrying them out whilst the machine is working, as in Figure 2.3.11.

The proposed method should always be tested before finalizing. Define the agreed method so that it can readily be followed and act as a basis for later checking.

Implement the new method by gaining the acceptance of the operational personnel and their managers and then ensuring the correct training is given.

Maintain the new methods by periodically checking that they are being followed and that any improvements are incorporated into the defined (standard) method.

Work measurement

There is a common saying ‘Before anything can be controlled, it must first be measured!’. This is the basic task of work measurement

Accurately measuring the time taken gives a firm basis for planning and control. It also allows management to prepare accurate estimates; determine capacity and its utilization; determine operatives’ performance; and give a sound basis for calculating incentive earned in PBR schemes.

Work measurement requires specialized training. It should be carried out only by personnel experienced in the process under study so that optimal conditions are being measured. It is not uncommon for trade union representatives to be trained in work measurement techniques and even be part of the work study team.

Time study is the most common method, although increasingly simulation is being used. A stop watch is used to determine the exact time required for a set operation. The measured time is adjusted depending on the operative’s effectiveness to get a basic time. It is then adjusted to give ample allowance for recovery from fatigue.

Rating

To measure work content, the work study observer has not only to record the time taken but also has to apply a judgement on the operative’s effectiveness. This judgement is called RATING and is a combination of effectiveness; speed; effort and attention.

The rating is carried out to a scale termed the BSI 0–100 scale. There are two fixed points on this scale – 0 for ‘not working’ and 100 for ‘standard (incentive) performance’. Normally ratings only in the range 75–125 are observed during a study. These can be described as:

Taking the study

Just as in method study, there is a set procedure to ensure that the study produces an accurate and usable time:

• Set method: The study should only be carried out on an agreed method. This includes all data such as machine speeds and feeds, fixtures required, position of all tools and components.

• Divide complete job into elements: In order to ensure ease of taking both elapsed time and rating, the entire job should be broken down into easily recognizable small elements of between 0.1 and 1.0 min. The breakpoints between elements should be made easily recognized – e.g. laying down a tool, pressing a button, etc.

• Carry out study: Record start and stop times. Every event during the study should be noted.

– Standardize times: Convert every observed time into a normalized time by multiplying by the observed rating:

| Observed time | = | 0.45 min |

| Observed rating | = | 90 |

| Normalized time | = | (0.45 × 90/100) = 0.405 min |

– Select representative time: Table all standardized times for each element and select a representative time for that element:

Selected representative value by discounting any ‘odd’ values, such as those crossed out, and averaging the remainder:

• Apply compensating rest allowance (CRA) to each element to compensate for energy expended carrying it out. This produces a standard time:

| Standard time | = | normalized time × (100 + CRA)/100 |

| If normalized time | = | 0.41 and CRA is 15% then |

| Standard time | = | 0.41 × (100 + 15)/100 = 0.4715 |

• Decide frequency of element: Where an element occurs every time, its standard time will be allowed once per component.

Some elements, such as fetching material or tooling may not happen once for each product. The selected time is reduced to that proportionate for one product.

If an element only occurs once every 10 components then the allowed standard time for that element per component = standard time per occurrence/10.

Add all allowed element times to give the standard time for the whole operation. This is normally issued in two standard digit formats.

• Issue agreed standard time and output per hour at 100 performance to operative and get their agreement.

Check the accuracy by carrying out production studies at set intervals.