THE OBJECTIVE OF THIS CHAPTER IS TO ACQUAINT THE READER WITH THE FOLLOWING CONCEPTS:

Developing and implementing a risk-based audit strategy

Understanding how to structure an audit

Implementing the principles of quality into audit activities

Planning required for specific audits

Implementing risk management and control practices while maintaining independence

Understanding qualifications and competence requirements

Conducting audits in accordance with standards, guidelines, and best practices

Knowing the types of controls and how they are implemented

Understanding the effect of pervasive controls on audits

Acquiring and using proper audit evidence

Understanding the new challenge of electronic discovery

Dealing with conflict, potential risks, and communicating to stakeholders

Conducting audit documentation and reports

During an audit, it is important to remember that all decisions and opinions will need to be supported by evidence and documentation. It is the auditor's responsibility to ensure consistency in the audit process. An audit quality control plan should be adopted to support these basic objectives.

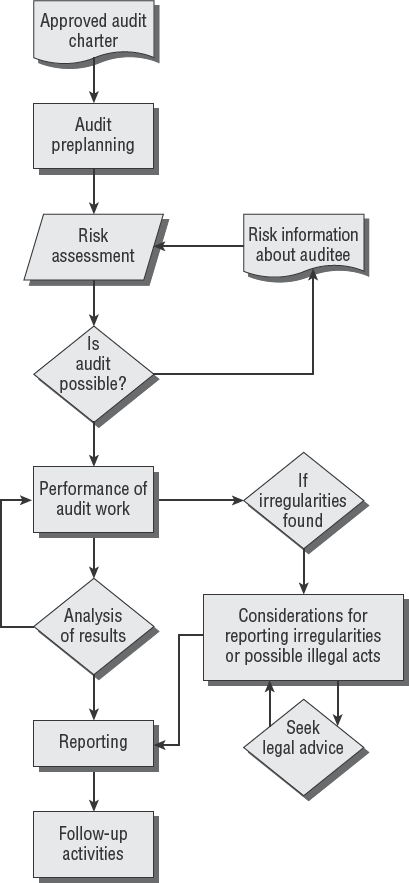

There are 10 audit stages to be aware of when performing an audit. A CISA needs to be aware of their duties in each of these stages:

Approving the audit charter or engagement letter

Preplanning the audit

Performing a risk assessment

Determining whether an audit is possible

Performing the actual audit

Gathering evidence

Performing audit tests

Analyzing the results

Reporting the results

Conducting any follow-up activities

In this chapter, you will look at each of these stages in detail along with various procedures used during the audit. Figure 2.1 illustrates a simple flowchart of the audit process. The actual execution of the audit will be more complex.

We will begin with the process of establishing an audit charter in order to gain the authority to perform an audit.

The first audit objective is to establish an audit charter, which gives you the authority to perform an audit. The audit charter is issued by executive management or the board of directors.

The audit charter should clearly state management's assertion of responsibility, their objectives, and delegation of authority. An audit charter outlines your responsibility, authority, and accountability:

- Responsibility

Provides scope with goals and objectives

- Authority

Grants the right to perform an audit and the right to obtain access relevant to the audit

- Accountability

Defines mutually agreed-upon actions between the audit committee and the auditor, complete with reporting requirements

Each organization should have an audit committee composed of business executives. Each audit committee member is required to be financially literate, with the ability to read and understand financial statements including balance sheets, income statements, and cash flow statements. The audit committee members are expected to have past employment experience in accounting or finance, and hold certification in accounting. A chief executive officer with comparable financial sophistication may be a member of an audit committee.

The purpose of the audit committee is to provide advice to the executive accounting officer concerning internal control strategies, priorities, and assurances. It is unlikely that an executive officer will know every detail about the activities within their organization. In spite of this, executive officers are held accountable for any internal control failures. Audit committees are not a substitute for executives who must govern, control, and manage their organization. The audit committee is delegated the authority to review and challenge the assurances of internal controls made by executive management.

The audit committee is expected to maintain a positive working relationship with management, internal auditors, and independent auditors. The committee manages planned audit activities and the results of both internal and external audits. The committee is authorized to engage outside experts for independent assurance. Both internal auditors and external auditors will have escalation procedures designed to communicate significant weaknesses that have been identified. The auditor will seek to have the weaknesses corrected in order to give a positive assurance that the risk is appropriately controlled and managed. The head of the internal audit and the external audit representative should have free access to the audit committee chairperson. This ensures an opportunity to raise any concerns the auditor may have concerning processes, internal controls, risks, and limitations. This reporting relationship is shown in the following graphic.

The audit committee should meet on a regular basis, at least four times a year, to fulfill this requirement. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) requires executives to certify that all internal control weaknesses have been discovered, with full disclosure to the audit committee provided every 90 days.

The audit committee is responsible for issuing the audit charter to grant the authority for internal audits. The audit charter should be approved by the highest level of management as well as the audit committee. Authority also needs to be granted for an independent audit. A document called an engagement letter grants authority for an independent external audit.

The audit charter allows the delegation of an audit to an external organization via an engagement letter. The engagement letter helps define the relationship to an independent auditor for individual assignments. The letter records the understanding between the audit committee and the independent auditor.

Note

The primary difference between an engagement letter and an audit charter is that an engagement letter addresses the independence of the auditor.

Engagement letters should include the following:

All points outlined in the audit charter

Independence of the auditor (responsibility)

Evidence of an agreement to the terms and conditions (authority)

Agreed-upon completion dates (accountability)

The second audit objective is to plan the specific audit project necessary to address the audit objectives. Analysis should occur at least annually to incorporate the constant stream of new developments in both the industry and the auditing field.

Your audit objectives will include compliance to professional auditing standards and applicable laws. The IS auditor needs to be prepared to justify any deviation from professional audit standards. Deviation is a rare event.

As an auditor, you will need to consider the impact of the audit on the business operation. You will need to gain an understanding of the business, its purpose, and any potential constraints to the audit. Let's look at the questions an auditor could ask to gain insight of the business operation:

- Knowledge of the business itself

What are their specific industry regulations? For example, are they governed by the U.S. Occupational Safety & Health Administration, any financial securities regulations, or the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act because of offering employee medical benefits?

What are the business cycles? The retail industry operates on a schedule that begins Christmas holiday activities in September. Their busy season is at the end of the year, whereas the construction industry is busy from March through August.

What are the reporting cycles? Is their year-end on September 30 or December 31?

What are the critical business processes necessary for survival?

Are reports available from prior audits?

Will the auditors be able to tour the facilities? Which location and when?

Who should be interviewed? Will those people be available?

What are their existing plans? Are any new products, clients, or significant changes planned?

- Strategic objectives

The top executive sets a strategy with supporting definitions for the entire organization. This strategy defines what the business will be doing over the next three to five years. It answers the question of what the business will be engaged in. Is it the same industry or is it branching out into another market?

What is the direction and structure going forward?

What is the organizational plan for integrating IS?

What are the business objectives that IS will be expected to fulfill?

What are the defined IS goals?

What is the strategic plan for the next two to three years?

What are the supporting tactical plan steps during the next one to two years?

What work is occurring from now to the end of the year?

- Financial objectives

Businesses use a portfolio approach to manage their investments, keeping those with the highest return and discarding underperformers. What is the return on investment (ROI) goal for the current capital investment and related expenses?

How are assets managed?

How are costs allocated to departments and projects?

What is the budget and forecasting process?

What are the financial reporting objectives? Will the client need an integrated audit for SOX reporting?

What are the business continuity plans?

- Operational objectives for internal control

Operational activities focus on running the business within a budget period, usually within a 12- to 14-month window. The focus is on what should be done today and this year.

Should any policies or procedures be tested?

Will this be an administrative audit?

How is system administration managed?

How are performance metrics managed?

What is the method used for capacity planning?

What is the strategy and status of business continuity and disaster recovery plans? How many exercise tests have occurred this year?

What controls exist for managing network communications?

What is the nature of the last system audit? Are self-assessments used?

What are the staffing plans?

Figure 2.2 shows four basic areas related to the organization's business requirements.

Every IS auditor will need to provide details when significant restrictions are placed on the scope of an audit. You will need to review your audit objectives and risk strategy to determine whether the audit is still possible and will meet the stated objectives. The audit report should explain specific restrictions and their impact on the audit. If the restrictions preclude the ability to collect sufficient evidence, you should render no opinion or no attestation in the audit.

Examples of restrictions include the following:

Management placing undue restrictions on evidence use or audit procedures that could seriously undermine the audit objective

Inability to obtain sufficient evidence for any reason

Lack of resources or lack of sufficient time

Ineffective audit procedures

Auditors have been known to terminate an engagement if the client places restrictions that are too severe on the audit. It is not unheard of for a client to discharge an auditor after receiving accurate findings that are distasteful to the client. The replacement auditor may need to inquire why a prior auditor is no longer being used by the auditee.

In some instances, the auditee will need to establish a level of communication between the previous auditor and replacement auditor. The purpose of this communication is to ensure that the client is not trying to obstruct truthful findings. Blackouts, or missing audit periods, would be a concern shared by more people than just the auditor. Statement on Auditing Standard 84 (SAS-84) provides additional details if you ever encounter this situation.

Each audit is actually an individual project linked to an ongoing audit program. The IS auditor may be asked to perform a variety of audits, including the following:

- Product or service

Efficiency, effectiveness, controls, and life-cycle costs

- Processes

Methods or results

- System

Design or configuration

- General controls

Preventative, detective, and corrective

- Organizational plans

Present and future objectives

To be successful, the auditor needs to engage in a fact-finding mission. You will need to take into consideration business requirements that are unique to the auditee or common to their industry. Each business has its own opportunities, challenges, and constraints. Remember, the purpose of an audit is to help management verify assertions (claims). Proper planning is necessary to ensure that the audit itself does not disrupt the business, or waste valuable resources, including time and money.

Every audit should have a set of requirements and objectives in support of the ongoing program—for example, the controls and efforts necessary to comply with regulations such as SOX. It is not possible to test all the requirements in one monolithic audit, so we break down (decompile) the larger compliance requirements into a series of smaller audits (modular stages):

- Client duties

Every audit has a client who sets the scope, grants authority, and agrees to pay for the project. The client's duties include the following:

Set the scope

Specify the audit objectives

Grant access to the auditee and resources

Define the reporting structure and confidentiality requirements

- Auditee duties

The auditee is responsible for working with the auditor to do the following:

Confirm purpose and scope

Identify critical success factors (CSFs) and measures of performance

Identify personnel roles and responsibilities

Provide access to information, personnel, locations, and systems relevant to the audit

Cooperate with the gathering of audit evidence

Provide access to prior audit results or to communication with prior auditors if necessary

Specify reporting lines to senior management

Make their assertion of controls and effectiveness independent of the auditor

- Auditor duties

The auditor is responsible for the following:

Plan each audit to accomplish specific objectives necessary for annual compliance.

Identify specific standards used for the audit (such as PCI section 11, NIST 800-53 controls, ISO 27002 management objectives, SOX section 401 or 404, FIPS 142, and so forth).

Use a risk-based audit strategy.

Identify special requirements of confidentiality, security, and safety. The information encountered by the auditor may be sensitive because of competitive value or possible legal repercussions.

Identify specific procedures to be used for the audit. All procedures must be in writing.

Document how the audit procedures are linked with specific audit objectives.

Create a list of the evidence needed to review in order to prepare the audit findings.

Create a written project plan.

Identify resources required, including people, areas for access, hardware, and software.

Develop time and event schedules with estimated start and end times.

Provide audit cost estimates.

Specify a date when the auditee and client can expect to receive a final report.

Scheduling should be mutually agreed upon so there are no surprises. Surprise requests tend to damage the relationship rather than build confidence. Your auditee will wonder whether you are just an incompetent planner or if you have an ulterior motive. Surprises make the auditee leery, if not downright distrustful, of your intentions.

As an auditor, you need to understand the nature of the systems that your client desires to be audited. It would be nearly impossible to audit systems whose mission you do not understand.

During preplanning, it's important to review the capabilities of each member of the audit team. Is each member of the audit team up to the task? The engagement manager or lead auditor should be made aware if a member of the team is missing a certification or a clearance rating necessary to conduct the audit.

In addition, audit plans can change depending on whether the client is using a centralized or distributed system design. The location of IS facilities and personnel will need to be considered.

The auditor needs to demonstrate due care as a professional in both planning and execution. There are a number of definitions for the word care:

Basic care is defined as the bare minimum necessary to sustain life without negligence.

Ordinary care is better than basic and provides an average level of customary care in the absence of negligence.

Extraordinary care is defined as that which is dramatically above and beyond what a normal person would offer or a situation would entail.

Various degrees of care could fall under the definition of due care. The degrees of care are proportional to the level of risk or loss that could occur. Negligence is the absence of care. A conscientious person will exercise due care in the performance of their job. Failure to exercise due care would be negligence.

Every audit is a systematic approach of testing samples of evidence to measure compliance against a designated standard. Anyone with the correct attitude has the potential to be a good auditor after proper training. Let's start with two foundation-level audit objectives:

To test control implementation to see whether the auditee has implemented adequate safeguards

To comply with legal requirements that specify procedures necessary to remain legal

It is not unusual to discover missing controls or the absence of formally documented legal requirements. Auditors may discover that the auditee's understanding of the requirements is quite vague—but no need to fear, because you can be the super auditor with a solution. You can use a special method called the process technique, invented by Walter Shewhart. Shewhart conceived the quality techniques used by Edwards Deming and Philip Crosby.

The purpose of the process technique is to guide a repeating cycle of constant improvement for a process or system. It can be used to identify specific action items necessary to accomplish vague requirements, such as "maintain adequate security." Let's implement the four basic steps used to perform Shewhart's process technique (Plan, Do, Check, Act):

- Plan

Is there a plan or a method?

Did management convey the importance of this objective by sponsoring a policy?

Has the auditee established what needs to be done by identifying specific tasks or procedures?

The auditor may find evidence including outlines, procedures, flowcharts, specifications, or notes.

- Do

Now you look to see whether the plan, procedure, or method is being followed according to their plan. Is the work output matching their plan?

Look for the existence of status reports, meeting records, employee training, or other documentation used in their work area.

- Check

Is anyone monitoring the process? Is there a quality control check or peer review being used? If so, what is the acceptable criterion?

How are problems discovered and reported? Look for compliance testing and evidence of noncompliance, such as rework or discards. What metrics are used? Look for deviation reporting.

- Act

Inevitably, there are differences between what was expected in the plan and the actual outcome. This Act step refers to analyzing the differences, and then taking action to adjust the process so the problem is corrected. Action should always be taken to fix the problems as they are found.

Shewhart's famous graphic is shown next to illustrate the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle. Using this cycle made Deming famous. It will help you too.

A really smart auditor will focus on situations that are not normal to determine how decisions are made. Auditors should always be curious about how a decision was reached. What evidence is available to justify the decision? Whose approval was required?

A discussion of the audit process would not be complete without mentioning the specific differences between audits and assessments or control self-assessments. The auditee can work to improve their audit score between audits by using assessments and self-assessment techniques.

- Traditional audits

To employ the formal skills of a professional auditor is considered a traditional audit. In a traditional audit, the auditor manages the audit through the entire audit process and renders a final opinion.

Audits are used to specifically measure auditee claims against a reference standard. The audit generates a report viewed to represent a high assurance of truth. Audits are used in attest reporting engagements (when the auditor attests that the auditee claims are true).

The audit results may be used for regulatory licensing and external reporting.

- Assessments

Assessments are less formal and frequently more cooperative processes that scrutinize people and objects. A client may employ a professional auditor to work with the auditee. The goal is usually to "see what is out there." Assessments implement informal activities designed to determine the value of what may already exist. Value is based on relevance and fitness of use. An assessment report is viewed to have a lower value (moderate-to-low value) when compared to an audit. Assessments are excellent vehicles for training and awareness. The goal of an assessment is to help the staff create a sense of ownership while working toward improving their score.

Results of the assessment remain internal to the organization and are not eligible for use in regulatory licensing.

- Control self-assessments (internal)

A control self-assessment (CSA) is executed by the auditee. With a CSA, the auditor becomes a facilitator to help guide the client's effort toward self-improvement. The auditee uses the CSA to benchmark progress with the intention of improving their score. A great deal of pride can be created by the accomplishment of CSA tasks and learning the detail necessary to succeed in a traditional audit. Therefore, the CSA process can generate benefits by empowering the staff to take ownership and accountability.

Control self-assessment will not fulfill the independence requirement, so a traditional audit is still required. CSAs can be used to identify areas that are high risk and may need a more detailed review later.

Tip

Know the difference between audits and assessments. Audits are formal activities that are conducted by a qualified auditor and generate a high assurance of the truth. Audits can be used for licensing and regulatory compliance. Assessments are informal activities designed to determine the value of what may already exist. Value is based on relevance and fitness of use. The assessment is excellent for instilling a sense of ownership in the staff. Assessment results should remain internal to the organization.

As auditors, our goal is to report the truth and to educate our clients. Using traditional audits with a combination of lower-cost assessments will help our client become more successful. Now it's time to move forward into risk management.

After identifying a methodology for risk evaluation and control, the auditor will need to identify potential risks to the organization. The auditee will assist by providing information about their organization.

To properly identify risks, the auditor also needs to identify the following:

Assets that need to be protected

Exposures for those assets

Threats to the assets

Internal and external sources for threats

Security issues that need to be addressed

Part of documenting risk data is for the auditor to identify potential risk response strategies that can be used in the audit with each identified risk. The four risk responses are as follows:

- Accept (de facto)

Take your chances. Ignoring a risk is the same as accepting it. The auditor should be concerned about the acceptance of high-risk situations. By not taking action, the management team has automatically accepted the risk. Not making a decision and taking action means management has already accepted the risk.

- Mitigate (reduce)

Do something to lower the odds of getting hurt. The purpose of mitigation is to reduce the effect of the potential damage. Most internal controls are designed to mitigate risk.

- Transfer

Let someone else take the chance of loss by using a subcontractor or insurance. You can transfer the risk but not the liability for failure. Blind transfer of risk would be a genuine concern. This applies to outsourcing agreements and the reason for a right to audit clause in the contract.

- Avoid

Reject the situation; change the situation to avoid taking the risk.

An assessment of risk will usually include a list of all possible risks that threaten the business and your evaluation of how imminent they are.

Note

Toy manufacturer Mattel experienced the problem of inherited liability for distributing toys manufactured with hazardous lead paint (2007). Mattel was held responsible in the eyes of the public for failing to manage their subcontractor effectively. Unknown to Mattel, their subcontractor chose to ignore specifications in favor of using a lead-based paint. Mattel is under scrutiny for failing to detect the violation prior to shipping their toys. When you transfer risk, you still own the liability. Mattel is only one example of the inherited liability issue.

Note

Other examples of inherited liability include the pet food recall of 2007 caused by tainted flour in the ingredients. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration placed a widespread ban on fish from Chinese suppliers because of questionable practices by the subcontractors using illegal growth hormones. A quick Google search will yield many more examples of liability inherited from subcontractors.

Figure 2.3 shows the basic process of responding to risks. A CISA is expected to understand the different types of responses. Risk management principles will apply to your audit planning. Your client will select from similar choices in their decisions about the risks faced by their organization.

Performing a risk assessment is the next step after the audit objectives have been identified. The purpose of a risk assessment is to ensure that sufficient evidence will be collected during an audit. We will add a new term to your auditor vocabulary: materiality. Materiality refers to evidence that is significant and could change the outcome.

While searching for evidence, it is important to remember that you are not looking for 100 percent of all conceivable evidence. You are interested in material evidence that will be relevant to the outcome of your audit. Please keep in mind that it is easy to be distracted during an audit. You should focus your efforts on material evidence that either proves or disproves your specific audit objective. Your findings and opinion will be based on this material evidence.

An audit risk assessment should take into account the following types of risks:

- Inherent risks

These are natural or built-in risks that always exist. Driving your automobile holds the inherent risk of an automobile accident or a flat tire. Theft is an inherent risk for items of high value.

- Detection risks

These are the risks that an auditor will not be able to detect what they are looking to find. It would be terrible to report no negative results when material conditions (faults) actually exist. Detection risks include sampling and nonsampling risks:

- Sampling risks

These are the risks that an auditor will falsely accept or erroneously reject an audit sample (evidence).

- Nonsampling risks

These are the risks that an auditor will fail to detect a condition because of not applying the appropriate procedure or using procedures inconsistent with the audit objective (detection fault).

- Control risks

These are the risks that an auditor could lose control, errors could be introduced, or errors may not be corrected in a timely manner (if ever).

- Business risks

These are risks that are inherent in the business or industry itself. They may be regulatory, contractual, or financial.

- Technological risks

These are inherent risks of using automated technology. Systems do fail.

- Operational risks

These are the risks that a process or procedure will not perform correctly.

- Residual risks

These are the risks that remain after all mitigation efforts are performed.

- Audit risks

These are the combination of inherent, detection, control, and residual risks.

These are the same risks facing normal business operations. In the planning phase, an IS auditor is primarily concerned with the first three: inherent risk, detection risk, and control risk. All of the risks could place the business or audit in jeopardy and should be considered during some level of advance planning.

An auditor should create plans to allow for alternative audit strategies if an auditee has recently experienced an outage, service interruption, or unscheduled downtime. It would be unwise to pursue an audit before the business has ample time to restabilize normal operations. Plans should include an opportunity to reschedule without violating a legal deadline.

A good auditor remembers that setting priorities is their responsibility. You will need to assess the risk of the audit and ensure that priorities have been fulfilled. If you are unable to perform the necessary audit functions, it is essential that the issues be properly communicated to management and the audit committee. An audit without meaningful evidence would be useless.

The auditor will need to work with the auditee to define specific requirements and identify any third-party providers. You will need to review the auditee's organizational structure and to identify persons in areas of interest that are material to your audit.

Management has the ultimate responsibility for internal controls and holds the authority for delegation. Management may choose to delegate tasks to a third party (outsource). The outsource organization must perform the daily tasks as designated, but unfortunately management will still retain liability that cannot be delegated. Executive management will still be held responsible for any failures that occur with or at the outsource organization. The federal government has gone to great lengths to ensure that the decision maker (management) can be held fully accountable for their actions and liable for any loss or damage.

Organizations with outsourcing contracts and labor unions could be particularly difficult unless you have sufficient cooperation. In the case of labor unions, it is often necessary for the shop steward to be present and involved in all plans and activities. Failure to do so may result in an operational risk of the union workers walking off the job.

Outsourced activities will present their own challenges with potential restrictions on access to personnel and evidence. It would not be uncommon for a service provider to decline your request for an audit. Most outsource providers will attempt to answer such requests by supplying you with a copy of their latest SAS-70 report, which is a standard report format for service providers. Occasionally, when a client requests and receives the SAS-70 report from a service provider, the value of content in the SAS-70 report may be overstated.

The purpose of the SAS-70 is to eliminate multiple organizations from individually auditing the service provider. You can expect that several points of detailed evidence you requested will have been filtered or masked in the SAS-70 report. Your client's original outsource contract should have included a provision for the right to audit along with the service-level agreement. It must be clearly stated whether the SAS-70 is acceptable or if an individual audit is required. Performing your own audit adds cost but offers high levels of control. Be advised that some outsource providers run on a different business schedule than their clients.

The next objective in the audit is to perform the actual audit. Here you will need to make sure you have the appropriate staff, ensure audit quality control, define auditee communications, perform proper data collection, and review existing controls.

You will need to have personnel for the audit and to define the audit's organizational structure. You also will need to create a personnel resource plan, which identifies specific functions and skill sets necessary to complete your audit objectives. Individual skills and knowledge should be taken into consideration while planning your audit. Remember, it's impossible for the auditor to be an absolute expert in everything.

You will need to rely on the work of others, including your own audit team members, subcontractors, and possibly members of the client's staff. You should create a detailed staff training plan that is reviewed at least semiannually and before each audit. The time to train or retrain personnel is before the audit begins.

The auditor will lead persons with specialized skills, including the use of database scanners and other automated audit tools. A skills matrix should be developed, which indicates areas of knowledge, proficiency, and specialized training required to fulfill the audit. You use the skills matrix to identify members of the audit team according to the specific tasks each will perform. The purpose of the skills matrix is to ensure that the team has the right people with the right qualifications working on the right task. You use the matrix to demonstrate gaps and training needs. This discourages management from assigning you an unskilled "warm body." Table 2.1 shows a sample skills matrix.

Table 2.1. Sample Skills Matrix

Person | Training or Certification | Related Work Experience | Audit Task |

|---|---|---|---|

M. Anderson | IA, CISA | Internal auditor | Audit task 8: Review of existing policies and records for PCI user training, all security, system configuration, and incident response. |

CISA, Network+, CCNA | PCI and PCI section 11 testing | Audit task 9: PCI section 11 network perimeter analysis. | |

R. Martin | CISA | XP admin, BSD Unix admin | Audit task 10: Conduct enumeration scan of network hosts and open ports. Exclude "Zeus" server and customer service computers. |

Audit task 14: Select logs for review. Supervise and assist in review with B. Goldfield performing task. | |||

B. Goldfield | BS Computer Science | Intern, system analyst | Audit task 14: Catalog system log file data for analysis of past events to forensic-test the incident response. |

Occasionally, finding a competent, independent expert in database administration for a particular vendor on your project may prove difficult. However, you might be able to train a member of the client's support staff to provide sufficient assistance to complete the audit.

Auditors frequently use the work of others as long as the following conditions are met:

Assess the independence and objectivity of the provider.

Determine their professional competence, qualifications, and experience.

Agree on the scope of work and approach used.

Determine the level of review and supervision required.

If these conditions are met, the auditor may choose to use the work of others. A CISA should have serious concerns if the work does not meet their audit evidence requirement for any reason. You can use only evidence of sufficient quality, quantity, and relevance. Failure to meet this requirement may require a change in the audit scope or canceling the audit.

Tip

Competence means having the right training, related experience, discipline, and qualifications for the job. Qualifications include recognized certification with the proper clearance for the job. Clearance may include having both permission to work the audit and a valid security clearance, especially in government auditing.

Quality does not happen automatically. It is a methodology that must be designed into your process and not just inspected afterward. Quality control is necessary in every audit.

Let's take a moment to define what quality is and how to recognize quality. We can do this by using three easy-to-remember points:

Quality is defined as conformance to specifications.

Planning and prevention create quality. Quality does not occur by post appraisal.

The standard of performance is zero defects, not by just getting "close enough." Sixth and seventh sigma do not reach zero defects. Quality can be measured by the price of failure (nonconformance).

Audit standards, guidelines, and procedures were developed to promote quality and consistency in a typical audit. The ISACA audit standards were developed to assist CISA auditors in performing audits. Additional guidance can be obtained by reading the ISACA audit guide at www.isaca.org/standards.

Your audit will need a variety of quality performance metrics to ensure success. When designing a quality control process, an auditor should consider doing the following:

Use an audit methodology (documented plan and procedures).

Gain an understanding of the auditee needs and expectations.

Keep a checklist of the tasks to be accomplished.

Respect business cycles and deadlines.

Hold client interviews and workshops.

Use customer satisfaction surveys.

Agree to terms of reference used by client, auditee, and auditor (discussed in Chapter 1, "Secrets of a Successful IS Auditor").

Establish audit performance metrics.

Measure audit plan to actual performance.

Respond to auditee complaints.

Quality can vary according to the requirements set forth by management. The auditor must take all the necessary steps to ensure that audit work is performed with very high standards of quality to generate a high assurance of the truth. Anything less will make you and the images of our profession appear questionable. High standards always bring respect.

The auditor must work with management to define the auditee communication requirements.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the auditee often feels at a disadvantage to the auditor. Without effective communication, the auditee will feel disillusioned, confused, or disconnected from the audit. Each of these conditions would be undesirable; audits without client buy-in would be a major disaster.

Tip

Occasionally, the auditee may request to see information concerning the audit plan. Depending on your assignment, it may be acceptable to allow the auditee to view your blank checklists; however, the auditor's notes should remain confidential during the audit. It is usually not a good idea to give the auditee copies of your blank forms because doing so could provide the foundation for disputes or engineered answers.

It is your job as the auditor to be a "second set of eyes" in reviewing the present condition at the organization. You are responsible for reporting accurate findings to senior management and the audit committee. The audit charter should assist you by defining the required level of auditee communication.

To be effective in your communication, you need to consider several points, including the following:

Describing the audit's purpose, service, and scope

Dealing with problems, constraints, and delays

Responding to client questions and complaints

Dealing with issues outside the scope of this particular audit

Understanding timing and scheduling—knowing when they expect the work to occur

Following the reporting process—knowing when and how the client wants to hear from you

Obtaining an agreement of your findings with your client

Implementing confidentiality, implementing the principle of least privilege (need to know)

Providing special handling for evidence of irregularities or possibly illegal acts

Nothing will replace the simple act of asking the client what level and frequency of communication they expect. The preceding points are simply a starting position. You should synchronize the auditee communication plan with your own internal audit team communication plans.

During the planning process, the auditor will need to gain approval from management for access to the appropriate staff personnel. A member of the audit team may be assigned to coordinate everyone's schedule.

Now is a good time to introduce some of the data collection techniques that auditors use in audits.

As part of the planning process, the auditor needs to determine how data will be gathered for evidence to support the audit report. To collect useful data, the savvy auditor will use a combination of techniques, including the following:

- Staff observation

You can observe staff in the performance of their duties. Auditor observation is a powerful form of evidence.

- Document review

Remember, the evidence rule will apply as you review existing documentation. Presence of a document does not mean it is actually in use. You should review the auditee documentation and any related legal documentation. Legal documentation may be either contracts or regulatory laws.

- Interviews

You can interview selected personnel appropriate to the audit. Be sure to structure the timing and questions for the interview. You need to ensure that the questions are consistent and to allow extra time to discuss any interesting points raised.

- Workshops

Workshops can generate awareness and understanding. The audit committee may be a good audience for a workshop. Well-executed workshops can save time compared to individual interviews.

- Computer assisted audit tools (CAAT)

Newer auditing software does a fabulous job of checking configuration settings, user account parameters, system logs, and other time-consuming details.

- Surveys

Conducting surveys is a tried-and-true method of obtaining cheap and easy answers. Unfortunately, the truthfulness of individual responses raises questions about the survey's consistency and resulting trustworthiness. People may answer the question using a skewed perspective, or just respond with answers they believe you want to hear, regardless of the truth. Overall reliability of the survey remains an ongoing concern.

Each technique has its advantages and disadvantages. For example, surveys offer an advantage of time but have the disadvantages of inconsistency and limited response. A survey cannot detect a personal mannerism such as hesitancy, surprise, or restlessness.

An auditor can observe an auditee during an interview and ask additional probing questions based on the auditee response. The auditor weighs each response in an attempt to create consistent scoring of answers by multiple interview subjects. Interviews consume more time but can gather additional information.

Surveys may execute quickly but carry extra administrative support burdens. It will take time and resources to create the survey, distribute the survey, track responses, provide answer assistance, ensure quality control, and tally the results. Because of human nature, people will seldom answer a survey in a manner that reduces their agenda and perceived value to an organization.

Tip

Most clients will be impressed if you demonstrate genuine interest and take good notes. It will help you obtain auditee buy-in and make them feel the audit report will contain statements of value. Just be sure to avoid the perception of an interrogation.

Every auditor should consider two fundamental issues concerning internal control:

- Issue 1: Management is often exempt from controls. "Ye who make the rules might try to avoid those rules."

Management has the responsibility of installing controls for the organization, yet some of the executives themselves are exempt from their own control. An excellent set of examples is noted at the beginning of Chapter 1, where multiple executives fraudulently altered records. One of the fundamental purposes of an audit is to determine whether executives are providing an honest and truthful representation based in fact.

- Issue 2: How controls are implemented determines the level of assurance.

Implementing strong controls contributes to the level of assurance, which may be confirmed by the auditor. Strong assurance means it represents a 95 percent or greater degree of truth. Unsatisfactory implementation of controls compromises the overall objectives. No auditor can provide a satisfactory report if the controls are improperly implemented or insufficient for their objective.

Let's review the basic framework of controls according to the ISACA standards. ISACA based their standards on the common auditing guidelines for financial audits as well as the government guidelines for auditing and for the computer environment. Information systems controls are composed of four high level controls: general controls, pervasive IS controls, detailed IS controls, and application controls. This clarification is required because portions of the financial audit techniques may not be appropriate for some IS audits. Computer environments can be rather complex and abstract.

- General controls (Overall)

This is the parent class of controls governing all areas of the business. Examples of general controls include separating duties to prevent employees from writing their own paychecks and creating accurate job descriptions. We expect management to implement administrative controls to govern the behavior of their entire enterprise. General controls also include defining an organizational structure, establishing HR policies, monitoring workers and the work environment, as well as budgeting, auditing, and reporting.

- Pervasive IS controls (Technology)

A pervasive order or pervasive control defines the direction and behavior required for technology to function properly. The concept of pervasive control is to permeate the area by using a greater depth of control integration over a wide area of influence. Internal controls are used to regulate how the business operates in every area of every department.

The IS function uses pervasive controls in the same manner as a manufacturing operation, bank, or government office. Pervasive controls are a subset of general controls with extra definition focused on managing and monitoring a specific technology. For example, pervasive IS controls govern the operation of the information systems duties.

Pervasive IS controls are used across all internal departments and external contractors. Proper implementation of pervasive IS controls improve the reliability of the following:

Overall service delivery

Software development

System implementation

Security administration

Disaster recovery and business continuity planning

The lack of pervasive IS controls, or weak controls, indicates the possibility of a high-risk situation that should draw the auditor's attention. Lower-level detailed controls will be compromised if the pervasive controls are ineffective.

At the pervasive control level, the auditor needs to consider the experience level, knowledge, and integrity of IS management. Look for changes in the environment or pressure that may lead to concealing or misstating information. This problem is prevalent when users manage their own departmental systems separate from the IT department. External influences include outsourcing, joint ventures, and direct relationships. Internal influences include flaws in the organizational structure or reporting relationship where a built-in conflict may exist.

- Detailed IS controls (Tasks)

Specific tasks require additional detailed controls to ensure that workers perform the job correctly. Detailed controls refer to specific steps or tasks to be performed. In the finance department, a specific set of controls is practiced when creating a trial balance report. Detailed IS controls work in the same manner to specify how system security parameters are set, how input data is verified before being accepted into an application, or how to lock a user account after unsuccessful logon attempts. Detailed IS controls specify how the department will handle acquisitions, security, implementation, delivery, and support of IS services.

An auditor investigating the IS controls should consider findings from previous audits in the subject area. Give consideration to the amount of manual intervention required, the activities outside the daily routine, and the susceptibility of bypassing the IS controls. A smart auditor will always consider the experience, skills, and integrity of the staff involved in applying the controls.

- Application controls (Embedded in programs)

This is the lowest subset in the control family. All activity should have filtered through the general controls, then the pervasive controls and detailed controls, before it reaches the application controls level. The higher-level controls help protect the integrity of the application and its data. Leaving an application exposed without the higher-level controls makes as much sense as leaving a child naked in the woods to fend for itself. Just like children, the application needs to be sheltered and protected from harm.

Management is responsible for having applications tested prior to production through a recognized test method. The goal is to provide a technical certification that each system meets the requirements. Management has to sign a formal accreditation statement granting their approval for the system to enter production based on fitness of use and accepting all responsibilities of ownership. Accreditation makes management accountable for system performance and liability of failure (who to blame or who to reward).

The next step in the planning process is to review the existing internal controls that are intended to prevent, detect, or correct problems. Management is responsible for designating and implementing internal controls to protect their assets. You can obtain initial information about existing controls by reviewing current policies and procedures, and later by interviewing managers and key personnel. The purpose of internal controls can be classified into one of three categories:

- Preventative

Controls that seek to stop (prevent) the problem from occurring. A simple example is prescreening job applicants for employment eligibility. Synonyms for preventive controls include words such as proactive or deterrent activities designed to discourage or stop a problem.

- Detective

Controls that are intended to find a problem and bring it to your attention. Auditing is a detective control for discovering information.

- Corrective

Controls that seek to repair the problem after detection. Restoring data from a backup tape after a disk drive failure is a corrective control. Reactive control is a synonym of corrective control.

Controls from the three mid-level categories are implemented by using one of the following three methods:

- Administrative

Using written policies and procedures (people based)

- Technical

Involving a software or hardware process to calculate a result (special technology)

- Physical

Implementing physical barriers or visual deterrents (building design)

The auditor should be concerned with the attitude and understanding demonstrated by the auditee. An excellent exercise is to ask the auditee to which category their control would best apply. You may hear some unique and often incorrect responses. The process of reviewing the controls to prevent, detect, or correct is an excellent awareness generator with your auditee.

Table 2.2 lists some examples of these control types.

Table 2.2. Controls and Methods of Implementation

Control Type | Implementation Method | Some Examples |

|---|---|---|

Preventative "stops" | Administrative | Hiring procedures, background checks, segregation of duties, training, change control process, acceptable use policy (AUP), organizational charts, job descriptions, written procedures, business contracts, laws and regulations, risk management, project management, service-level agreements (SLAs), system documentation |

Technical | Data backups, virus scanners, designated redundant high-availability system ready for failover (HA standby), encryption, access control lists (ACLs), system certification process | |

Physical | Access control, locked doors, fences, property tags, security guards, live monitoring of CCTV, human-readable labels, warning signs | |

Detective "finds" | Administrative | Auditing, system logs, mandatory vacation periods, exception reporting, run-to-run totals, check numbers, control self-assessment (CSA), risk assessment, oral testimony |

Technical | Intrusion detection system (IDS), high-availability systems detecting or signaling system failover condition (HA failure detection), automated log readers (CAAT), checksum, verification of digital signatures, biometrics for identification (many search), CCTV used for logging, network scanners, computer forensics, diagnostic utilities | |

Physical | Broken glass, physical inventory count, alarm system (burglar, smoke, water, temperature, fire), tamper seals, fingerprints, receipts and invoices | |

Corrective "fixes" | Administrative | Termination procedures (friendly/unfriendly), business continuity and disaster recovery plans, outsourcing, in sourcing, implementing recommendations of prior audit, lessons learned, property and casualty insurance |

Technical | Data restoration from backup, high-availability system failover to redundant system (HA failover occurs), redundant network routing, file repair utilities | |

Physical | Hot-warm-cold sites for disaster recovery, fire-control sprinklers, heating and AC, humidity control |

When you exercise this awareness game of preventative, detective, and corrective controls, it is interesting to notice how technology-oriented people will provide an overt emphasis on technology, while nontechnology-oriented people will focus on administrative and physical controls. If your background is technology, you will need to consider administrative or physical solutions to approach a reasonable balance of controls. Nontechnology-oriented people will need to force their emphasis to include technical controls and achieve a similar level of balance.

The secret to achieving strong controls is to implement layers. The minimum for an effective control is to have at least one point in each of the three areas: preventative, detective, and corrective. For example, a policy without a detective mechanism or a corrective mechanism is not enforceable. The strongest controls implement all nine layers (Preventative, Detective, Corrective implemented using administrative methods, physical methods and technical methods).

The preventative control, for example, would include an administrative policy with technical protection and physical signs or barriers. A corresponding detective control would be implemented with authorization to audit proper job descriptions and procedures. The detective control would include technical methods, such as intrusion, and detection and physical indicators, such as a video recording of people's activity in secure areas. The control would be coupled with corrective actions—such as manual procedures for isolation, and technical recovery using data restored from backup tapes or physical replacement. This is referred to as depth of controls.

Strong control = multiple preventive controls + multiple detective controls + multiple corrective controls

Weak control = shallow bare minimum control + implementation or no implementation

Now that we have covered the basic preventative, detective, and corrective controls, it is time to move on to the impact of pervasive controls.

Every good auditor understands the necessity of collecting tangible and reliable evidence. You read an introduction to the evidence rule in Chapter 1. Although you may really like or admire the people who are the subject of the audit, your final auditor's report must be based on credible factual evidence that will support your statements.

Consider for a moment something not related to IS auditing: police investigations or famous television courtroom dramas. Every good detective story is based on careful observation and common sense. A successful detective searches for clues in multiple places. Witnesses are interviewed to collect their versions of the story. Homes and offices are tirelessly searched for the minutest shred of relevant evidence. Detectives constantly ask whether the suspected individual had the motive, opportunity, and means to carry out the crime. The trail of clues is sorted in an attempt to determine which clues represent the greatest value and best tell the story. Material clues are the most sought after. From time to time, the clues are reviewed, and the witnesses reinterviewed. The detective orders a stakeout to monitor suspects. Ultimately, the suspects and clues of evidence are brought together in one place for the purpose of a reenactment. Under a watchful eye, the materially relevant portions of the crime are re-created in an attempt to unmask the perpetrator. In the movies, the detective is fabulously successful, and the criminal is brought to justice.

Unfortunately, IS auditing is not so dramatic or thrilling to watch. A CISA candidate needs to possess a thorough understanding of evidence, because IS auditing is centered on properly collecting and reviewing evidence. Let's start with a short discussion on the characteristics of good evidence.

Evidence will either prove or disprove a point. The absence of evidence is the absence of proof. In spite of your best efforts, if you're unable to prove those points, you would receive zero credit for your efforts. An auditor should not give any credit to claims or positive assertions that cannot be documented by evidence. No evidence, no proof equals no credit.

Tip

All auditees start the audit with zero points and have to build up to their final score.

There are two primary types of evidence, according to legal definition:

- Direct evidence

This proves existence of a fact without inference or presumption. Inference is when you draw a logical and reasonable proposition from another that is supposed to be true. Direct evidence includes the unaltered testimony of an eyewitness and written documents.

- Indirect evidence

Indirect evidence uses a hypothesis without direct evidence to make a claim that consists of both inference and presumption. Indirect evidence is based on a chain of circumstances leading to a claim, with the intent to prove the existence or nonexistence of certain facts. Indirect evidence is also known as circumstantial evidence.

An auditor should always strive to obtain the best possible evidence during an audit. Using direct evidence is preferable whenever it can be obtained. Indirect evidence represents a much lower value because of its subjective nature. An auditor may find it difficult to justify using indirect evidence unless the audit objective is to gather data after detecting an illegal activity. An audit without direct evidence is typically unacceptable.

You will attempt to gather audit evidence by using similar techniques as a detective. Some of the data you gather will be of high value, and other data may be of low value. You will need to continually assess the quality and quantity of evidence. You may discover evidence through your own observations, by reviewing internal documentation, by using computer assisted audit tools (CAAT), or by reviewing correspondence and minutes of meetings.

Examples of the various types of audit evidence include the following:

Documentary evidence, which can include a business record of transactions, receipts, invoices, and logs

Data extraction, which mines details from data files using automated tools

Auditee claims, which are representations made in oral or written statements

Analysis of plans, policies, procedures, and flowcharts

Results of compliance and substantive audit tests

Auditor's observations of auditee work or reperformance of the selected process

All evidence should be reviewed to determine its reliability and relevance. The best evidence will be objective and independent of the provider. The quality of evidence you collect will have a direct effect on the points you wish to prove.

Computer assisted audit tools (CAAT) are invaluable for compiling evidence during IS audits. The auditor will find several advantages of using CAAT in the analytical audit procedure. These tools are capable of executing a variety of automated compliance tests and substantive tests that would be nearly impossible to perform manually.

These specialized tools may include multifunction audit utilities, which can analyze logs, perform vulnerability tests, or verify specific implementation of compliance in a system configuration compared to intended controls.

CAAT includes the following types of software tools and techniques:

Host evaluation tools to read the system configuration settings and evaluate the host for known vulnerabilities

Network traffic and protocol analysis using a sniffer

Mapping and tracing tools that use a tracer-bullet approach to follow processes through a software application using test data

Testing the configuration of specific application software such as a SQL database

Software license counting across the network

Testing for password compliance on user login accounts

Many CAATs have a built-in report writer that can generate more than one type of predefined report of findings on your behalf.

Numerous advantages may exist, but they come at a cost. These expert systems may be expensive to acquire. Specialized training is often required to obtain the skills to operate these tools effectively. A significant amount of time may be required to become a competent CAAT operator.

Some of the concerns for or against using CAAT include the following:

Auditor's level of computer knowledge and experience

Level of risk and complexity of the audit environment

Cost and time constraints

Specialized training requirements

Speed, efficiency, and accuracy over manual operations

Need for continuous online auditing

Security of the data extracted by CAAT

Warning

A CISA may encounter individuals who are self-proclaimed auditors based solely on their ability to use CAAT software. You should consider this when using the work of others. The ability to use CAAT alone does not represent the discipline and detailed audit training of a professional auditor.

The new audit tools offer the advantage of providing continuous online auditing. You should be aware of the six types of continuous online auditing techniques:

- Online event monitors

Online event monitors include automated tools designed to read and correlate system logs or transaction logs on behalf of the auditor. This type of event monitoring tool will usually generate automated reports with alarms for particular events. A few examples include software that reads event logs, intrusion detection systems, virus scanners, and software that detects configuration changes, such as the commercial product Tripwire. (Low complexity.)

- Embedded program audit hooks

A software developer can write embedded application hooks into their program to generate red-flag alerts to an auditor, hopefully before the problem gets out of hand. This method will flag selected transactions to be examined. (Low complexity.)

- Continuous and intermittent simulation (CIS) audit

In continuous and intermittent simulation, the application software always tests for transactions that meet a certain criteria. When the criteria is met, the software runs an audit of the transaction (intermittent test). Then the computer waits until the next transaction meeting the criteria occurs. This provides for a continuous audit as selected transactions occur. (Medium complexity.)

- Snapshot audit

This technique uses a series of sequential data captures that are referred to as snapshots. The snapshots are taken in a logical sequence that a transaction will follow. The snapshots produce an audit trail, which is reviewed by the auditor. (Medium complexity.)

- Embedded audit module (EAM)

This integrated audit testing module allows the auditor to create a set of dummy transactions that will be processed along with live, genuine transactions. The auditor then compares the output data against their own calculations. This allows substantive integrity testing without disrupting the normal processing schedule. EAM is also known as integrated test facility. (High complexity.)

- System control audit review file with embedded audit modules (SCARF/EAM)

The theory is straightforward. A system-level audit program is installed on the system to selectively monitor the embedded audit modules inside the application software. Few systems of this nature are in use. The idea is popular with auditors; however, a programmer must write the modules. (High complexity.)

Table 2.3 summarizes the differences between these CAAT methods.

Table 2.3. Summary of CAAT Methods

CAAT Method | Characteristics | Complexity |

|---|---|---|

Online event monitors | Reads logs and alarms. | Low |

Flags selected transactions to be examined. | Low | |

Continuous and intermittent simulation (CIS) | Audits any transaction that meets preselected criteria, waits for the next transaction meeting audit criteria. | Medium |

Snapshot | Assembles a sequence of data captures into an audit trail. | Medium |

Embedded audit module (EAM) | Processes dummy transactions along with genuine, live transactions. | High |

System control audit review file with embedded audit modules (SCARF/EAM) | System-level audit program used to monitor multiple EAMs inside the application software. This is a mainframe class of control. | High |

CAAT simplifies the life of an auditor by automatically performing the more menial, repetitive, detail tasks. The auditor needs to consider the CAAT reports while tempering them with some basic commonsense observations.

New developments are occurring in legal procedures for courts. The increased use of computers has led to widespread reliance on electronic data records. In the old days, evidence could be discovered by rummaging through printed mail, business records, file cabinets, and the dusty storage warehouse. Electronic record keeping is a wonderful tool for automation, yet it can also perpetuate fraud, intentional omissions, or misrepresentation. Electronic discovery is the investigation of electronic records for evidence to be used in the courtroom.

The new legal standard for electronic discovery is referred to as e-discovery. These rules were created to aid auditors and investigators by requiring owners of electronic records to disclose their existence and to provide the data in a simple easy-to-read format (unencoded). Under e-discovery rules, the party who owns or possesses the data is required to perform the conversion and to certify that the contents are truthful and complete in their representation of the content. Put simply, the data owner is no longer permitted to use unintelligible or secret codes to keep database contents a secret from investigators.

State and federal courts are still debating the final rules for e-discovery. The law recognizes two parties: the producing party, which provides the evidence, and the receiving party, which receives the evidence. Here's what the auditor can expect until a final ruling is ratified:

Discovery starts with a conference between the parties to plan the discovery process. Any issues related to disclosure of electronically stored information should be identified.

The conference sets the scope to identify possible sources of information. The judge may be asked to include the decisions of the meeting in a court order.

Limitations on scope may be identified based on undue cost or undue burden of production. Limitations will be determined by the judge after considering assertions of both parties and the nature of the case. Discovery may be ordered if the requesting party shows good cause in support of a claim or defense.

The scope may include data available online on any system.

The scope may include recovering deleted data.

The scope may include searching standing data from backup media and other offline sources.

The scope may include discovery of email and email records.

A search protocol will be agreed upon by the parties or ordered by the judge.

Unless the parties agree otherwise, the format shall be PDF or TIFF images without alteration of format or removal of revision history.

The judge may order the costs to be allocated equally, or unequally if good cause is shown why the other party should bear the cost.

Sometimes portions of data, such as formulas and lawful business secrets, are protected by a claim of privilege. If privileged information is produced in discovery, it may be recalled for return, sequester, or destruction after notification is given to the receiving party with an explanation of the basis for privilege. The information may not be disclosed after notice is given, and the producing party must preserve the information until the claim is resolved.

Under rule 37, the court may not impose sanctions on a party for failure to provide electronically stored information that was lost as a result of routine good-faith operations, if the records preservation was not mandated by regulation or exceptional circumstances.

E-discovery applies to criminal cases and civil lawsuits. The courts have determined that using encryption to hide or to cover illegal activities will result in multiple criminal penalties. Failure to cooperate with e-discovery requests can result in fines or prosecution. E-discovery requests include access to audit company records, HR files, database files, financial systems, and email correspondence.

Note

The management of every organization, as well as auditors, need to learn more about the impact of e-discovery on their business activities. Awareness can prevent future legal headaches.

All evidence is graded according to four criteria. This grading aids the auditor in assessing the evidence value. It is important to obtain the best possible evidence. The four characteristics are as follows:

- Material relevance

Evidence with material relevance influences the decision because of a logical relationship with the issues. Materially relevant evidence indicates a fact that will help determine that a particular action was more or less probable. The purpose of material evidence is to ascertain whether the same conclusion would have been reached without considering that item of evidence. Evidence is irrelevant if it is not related to the issue and has no logical tendency to prove the issue under investigation.

- Evidence objectivity

Evidence objectivity refers to its ability to be accepted and understood with very little judgment required. The more judgment required, the less objective the evidence. As you increase the amount of judgment necessary to support your claims, the evidence quickly becomes subjective or circumstantial, which is the opposite of objective. Objective evidence is in a state of unbiased reality during examination, without influence by another source. Objective evidence can be obtained through qualitative/quantitative measurement, and from records or statements of fact pertaining to the subject of the investigation. Objective evidence can be verified by observation, measurement, or testing.

- Competency of the evidence provider

Evidence supplied by a person with direct involvement is preferred. The source of their knowledge will affect the evidence value and accuracy. A secondhand story still holds value by providing information that may lead to the evidence the auditor is seeking.

An expert is legally defined as a person who possesses special skill or knowledge in a science or profession because of special study or experience with the subject. An expert possesses a particular skill in forming accurate opinions about a subject; in contrast, a common person would be incapable of deducing an accurate conclusion about the same subject.

- Evidence independence

Evidence independence is similar to auditor independence, meaning the provider should not have any gain or loss by providing the evidence. Evidence supplied by a person with a bias is often questionable. The auditor should ask whether the evidence provider is part of the auditee's organization. Qualifications of the evidence provider should always be considered. A person with a high degree of detailed understanding is vastly more qualified than an individual of limited knowledge. Evidence and data gathered from a novice may have a low value when compared to data gathered by an expert. A person who is knowledgeable and independent of the audit subject would be considered the best source of evidence.

Table 2.4 lists examples of evidence grading. An IS auditor should always strive to obtain the best evidence, which is shown in the far right column.

Table 2.4. Example of Evidence Grading

Poor Evidence | Good Evidence | Best Evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|

Material Relevance | Unrelated | Indirect (low relation) | Direct (high relation) |

Objectivity | Subjective (low) | Requires few supporting facts to explain the meaning | Needs no explanation |

Unrelated third party with no involvement | Indirect involvement by second party | Direct involvement by first party | |

Competency of Provider | Biased | Nonbiased | Nonbiased and independent |

Evidence Analysis Method | Novice | Experienced | Expert |

Resulting Trustworthiness | Low | Medium | High |

Evidence is analyzed by using a structured test method to further determine the value it represents. The audit process itself represents a major portion of preparation work to support the analysis of actual evidence.

Note

Every test procedure must be documented in writing to ensure that a duplicate test for verification will yield the same result. Tests may need to be repeated quarterly or annually to measure the auditee's level of improvement. Each test execution should be well documented with a record of time, date, method of sample selection, sample size, procedure used, person performing the analysis, and results.

It is often a good practice to use video recording to document the test process when the execution of the test method may be challenged—for example, to videotape a forensic computer audit if the results may be subject to dispute by individuals who are unfamiliar with the process.

The evidence grading effort aims to improve the resulting trustworthiness of the evidence. A competent IS auditor who can gather evidence and provide expert analysis with a high evidence trustworthiness rating is quite valuable indeed.

An additional factor to consider in regards to evidence is timing. Evidence timing indicates whether evidence is received when it is requested, or several hours or days later. In electronic systems, the timing has a secondary meaning: Electronic evidence may be available only during a limited window of time before it is overwritten or the software changes to a new version.

We have discussed the character of evidence, evidence grading, and timing. The next section explains the evidence life cycle relating to the legal chain of custody.

The evidence will pass through seven life-cycle phases that are necessary in every audit. Every IS auditor must remain aware of the legal demands that are always present with regard to evidence handling. Failure to maintain a proper chain of custody may disqualify the evidence. Evidence handling is just as important for SOX compliance is it would be for suspected criminal activity. Evidence handling is crucial for compliance to most industry regulations.

Warning

Mishandling of evidence can result in the auditor becoming the target of legal action by the owner. Mishandling evidence in criminal investigations could result in the bumbling auditor becoming the target of both the owner and the alleged perpetrator of a criminal activity.

The seven phases of the evidence life cycle are identification, collection, initial preservation storage, analysis, post analysis preservation storage, presentation, and return of the evidence to the owner. The entire set of seven phases is referred to as the chain of custody. Let's go down the list one by one:

- Identification

The auditor needs to identify items that may be objective evidence lending support to the purpose of the audit. The characteristics of the evidence location or surroundings should be thoroughly documented before proceeding to the collection stage. All evidence shall be labeled, dated, and notated with a short description about its purpose or discovery. From this point forward, the evidence movements must be logged into a tracking record. Your client will not be happy if evidence is misplaced.

Note

It may be important to demonstrate how the evidence looked when it was discovered. Identification includes labeling and can include photographing physical evidence in an undisturbed state at the time of discovery.

- Collection

The collection process involves taking possession of the evidence to place it under the control of a custodian. Special consideration should be given to items of a sensitive nature or high value. The IS auditor needs to exercise common sense during the collection process. Client records need to be kept in a secure location.

Tip

For most audits except criminal investigations, the IS auditor should be cognizant of the liability created by taking the client's confidential records out of the client's office. We strongly advise that all records remain within the client's facility to relieve the auditor of potential liability. The best way to prevent accusations is to ensure that you never place yourself in a compromising position. Allow the client to remain responsible for evidence security. Just be sure to lock up each evening before you leave.