I realize that the way I’ve organized all these lighting situations may seem at first glance a little unexpected: waiting, chasing, then helping. Why not start, for example, with bright sunlight and then work through the times of day, then move on to different amounts of cloudiness? The reason is that while that might make complete sense to a meteorologist, it’s not really the way that light works for photographers, at least in my experience. There’s a huge difference in the way most photographers would think about and react to a succession of fine summer days than they would to a day of squalls passing overhead. The big difference, it seems to me, is between lighting you can reasonably plan for, and lighting that’s unexpected.

All of the lighting in this book is of the kind that’s handed to you by the place and the time. You could call it “found” lighting—most of it natural daylight, some of it the artificial lighting that illuminates homes, offices, and cities. As the title explains, I’m looking at how to capture lighting over which you have no real control. Constructed lighting, using flash or other lights designed for photography and filming, in studios, on interior and outdoor sets, is the subject of another book. The thought processes and working methods are completely different.

Loi Krathong celebration, Wat Prhathat Lampang Luang, northern Thailand, 1989

A very basic idea is the attractiveness of lighting, and why some kinds are more desirable than others to most photographers. This is a tricky subject, because it’s really about aesthetics and how people’s taste and judgment can differ—or coincide. Most of the time, people take it for granted that the light will look good under these conditions, but not so good under those. Think for a moment about what photographers and filmmakers call the Golden Hour. The “hour” is just approximate, but it means when the sun is low and bright, and it has its well known name because so many of us favor it and plan for it. And it features in this book, on pages 94–101. But why exactly? Why do most people find it visually attractive (and they certainly do)? Philosophically I don’t think there’s much value in in pursuing that question, and in the history of art and aesthetics it has never been completely answered. But what we can do very usefully is talk about being conventionally pleasing with light, and about doing the opposite, which is to buck the trend and challenging expectations.

Although I don’t have any ambitions to add more jargon to photography than there already is, the lighting for any shot has a beauty coefficient, or you could call it a likeability factor. The Golden Hour, for example, would score overall about 8 out of 10 on this, and a flat grey sky would come in at around 1 or 2. I’m halfway tempted, but will resist, putting scores like this on each lighting situation in the book. We all have our prejudices and expectations about good, boring, or ugly light, so there’s no need to hammer it home with a ratings system. What’s useful about such a beauty coefficient, however, is that it expresses what most people like. Deep down, it’s conventional, and that’s why there are many occasions when you might instead want to be different.

More than that, I like personally to think that most kinds of light are good for something, if only you think and work hard enough. It’s an intentionally positive, even charitable way of thinking about light, and not everyone would agree. You might think it’s going too far to expect a miserable, bleak wintry day in England, for example (we’re famous for weather and our complaining about it) to ignite any photographic passion. Yet, even now I’m sometimes surprised at the results from what I thought of at the time as disappointing light—so long as I persisted in the shooting.

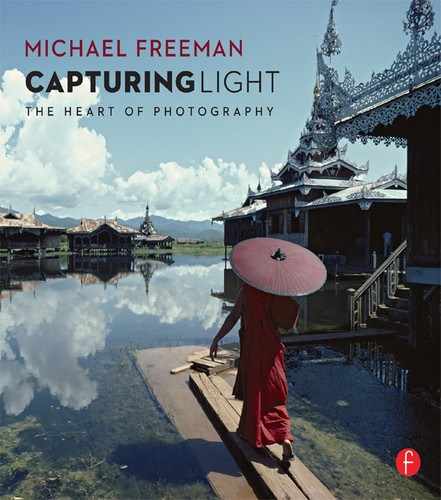

Wat Doi Kong Mu, Mae Hong Son, northern Thailand, 1982

One book that made a great impression on me, and made me think more about the quality, mood and overall visual atmosphere of light, was In Praise of Shadows, a slim volume written in 1933 by a Japanese novelist, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki. I read it when I was doing several books about Japanese interiors in an effort to get my head around what may be the most distinct and introverted design culture in the world. Tanazaki helped enormously. The title is perfect. He was giving the counterview to Western Modernism, with its Bauhaus-bright emphasis on flooding life with light and whiteness, with all the associations of progress and optimism. Actually, Tanazaki railed against all of this, writing in a sympathetic but melancholy way of the beauty and even color in darkness. Specifically though, he was having a go at electricity. At one point he maintains that “lacquerware decorated in gold was made to be seen in the dark.” Interesting idea—less light, not more, and that certain experiences call for a particular light. He writes about light in temples being dilute, with a pale, white glow. “Have not you yourselves,” he asks, “sensed a difference in the light that suffuses such a room, a rare tranquility not found in ordinary light?’” Close down and be somber, not unremittingly cheerful. Tanazaki made me realize how lighting contributes to mood.

Most of what follows is non-technical, but only if you define technical as strictly confined to camera and lens settings, calculations, and computer software. This ultimately comes down to exposure, and I dealt with that as exhaustively as I know how in Perfect Exposure. The aim here is to show how to work with natural and available light, and that starts with understanding its qualities. That in turn needs a vocabulary if we’re going to work with light rather than just enjoy it as a sensory experience. Normally, people don’t have that need, and so words to describe the ways in which it falls on scenes, people, and objects are thin on the ground. Most people simply take it for granted. In this, it shares a common difficulty with other sensory experiences, like taste and smell. There is a professional vocabulary, although it is by no means as evolved as the two big sensory industries—wine and perfume. There, the size of the business and the market has forced the professionals to develop a large and precise vocabulary, on the way to becoming a common language. Here, with light, I’ll be using terms like raking, sunstars, barred light, chiaroscuro, fall-off, directional, and fill. Most are self-evident, but where there’s any doubt, I’ll do my best to define them.