Sitting around waiting doesn’t sound like much of a management technique, let alone a light-management technique, but done properly it delivers the results. It depends, though, on knowing what you’re waiting for, and this understanding takes things to a different level. Natural light, which is mainly what we’re dealing with here, comes from a combination of climate, weather, and time of day. Climate means location, and you can plan for that by organizing a trip. Weather and time of day continue without any possibility of influence from you, and this is where intelligent waiting comes in. “Intelligent” because waiting involves planning, and it’s a very deliberate approach to photography. Most of all, it’s about knowing what light is possible from all the combinations, what each kind of light is good for in shooting, and how to extract the most from it in timing, framing, composition, viewpoint, and a sense of color (or black and white).

Practically, as a photographer, I divide light into the kinds I can expect, and the kinds that take me by surprise. This makes perfect sense for shooting, because they each prompt a different way of working. With the first group—the group in this first section of this book—you can anticipate and use your imagination to work out the kind of image you’re about to shoot. With the second, unpredictable group, you have to react to the situation as it appears. Naturally, there are borderline cases, such as a shaft of sunlight that spotlights a small part of a scene. If you’re just passing through a new place, and the weather is uncertain, this will probably come as a surprise. But in a location you know well, and in a bout of predictable sunny weather, that spotlight will be repeated, with a slight difference, the following day.

Shooting in the kinds of lighting described here in the Waiting section depends on having reasonable expectations. It also depends on having a feeling for what the light does to landscape, people, and buildings. This includes the more technical matters of contrast: where the shadows fall and how strong they are, how well or not the light separates a subject from its background, and how clearly it explains the shape and form of things. But it also goes further, into the realm of sensation and atmosphere, which are less easy to pin down, but nevertheless powerful components of a photograph. One thing I’m going to warn about is falling into line too easily with the accepted norms of attractive light for photography. Not every scene has to be gorgeous and lyrical. Imagery means variety, and hunting for the perfect—and therefore the same—golden light across a pretty landscape actually means giving up on your imagination and following the herd. I’ve done it myself, and it’s often hard to resist. It’s especially common in contemporary published landscape photography. The problem is that taking this approach means heading in the same direction as others—a sort of photographic gold rush. Just a caution.

Key Points

Precise Timing

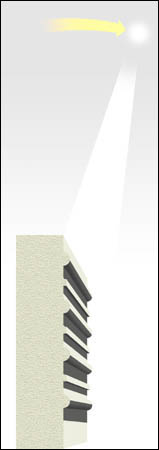

Elevation

Technology

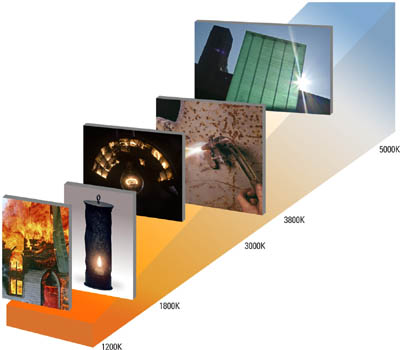

This is not a book about meteorology or trigonometry, but you’ll excuse me for a moment if I trip through some basics that will help in identifying the kinds of light that bring richness to photography; they matter more for this section than the following two. Time of day meets weather to create these many lighting situations, and behind them lay location and climate. Quite a lot to keep a handle on, particularly if you travel.

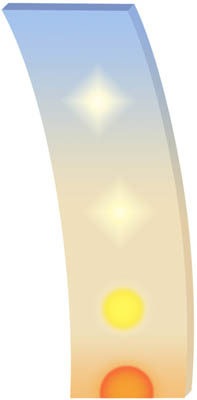

It helps, I think, first to subtract the weather and just concentrate on the sun and its passage through the sky. The key end-points, as you’d expect, are sunrise and sunset, and not only do these set the timing for the day’s light, but on either side of them, for about a couple of hours, the light not only changes more rapidly, but is also for various reasons especially favored for shooting. This means that most people like the light at these times of day, and even non-photographers start paying attention. Nevertheless, I learned early on that there’s little point asking around for when the sun rises and sets (standard practice before GPS and smartphones could give you a running commentary on the timetables). There are, in fact, relatively few professions and trades that live by the sun; photography happens to be one of them.

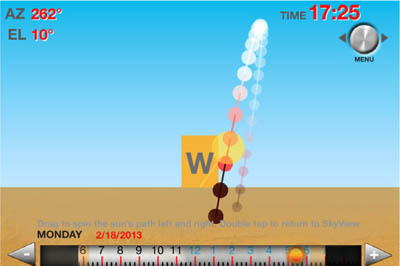

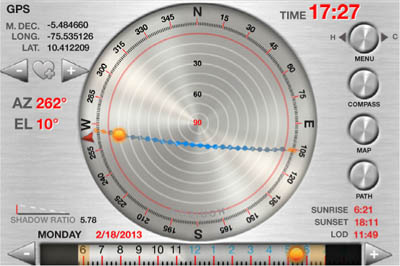

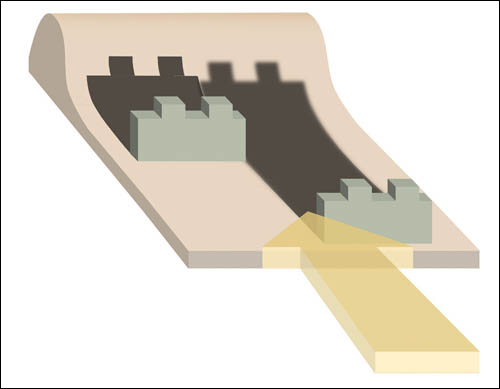

It makes every sense now to rely on phones, tablets, or laptops for daylight tables, without needing to calculate anything, but the track of the sun through the sky is a slightly different matter. It changes constantly—very slowly near the equator, more definitely in higher latitudes. Personally, I use a phone app called Helios, which was designed for cinematographers, and has everything from a clinometer to a shadow-length calculator. As long as it has my location, I can work out not only where and when the sun will hit the horizon, but also where and when it will clear a skyline ridge or a high-rise block.

Factoring in the weather dramatically multiplies the possibilities, for confusion as well as shooting opportunities, so be aware that certainty is rare. Weather includes everything from atmospheric haze to clouds and storms—basically anything that prevents the sky from being crystal clear—and it’s the subtleties of weather that create the many nuances of lighting that figure largely in the lives of photographers, filmmakers, and painters, but not too many others. ![]()

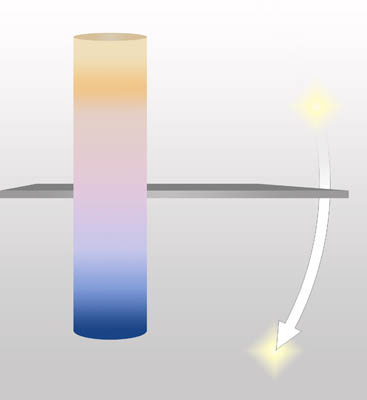

The sun’s height

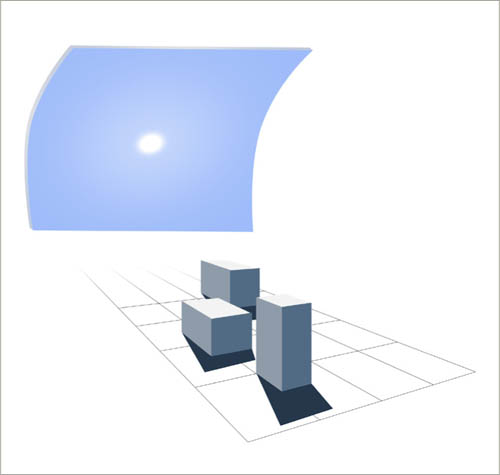

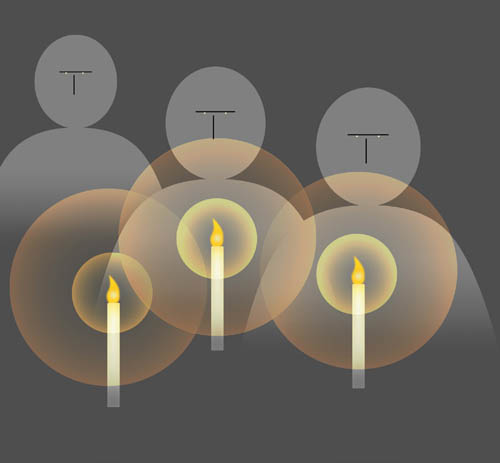

With Golden Hour taking up the lower 20º of the sun’s path above the horizon, it’s useful to be able to judge its height, particularly if you want to match this to tables. Approximately, then, if you hold your hand like this, arm out-stretched, these are the heights: 8º for the top of the palm and 15º for the tip of the thumb. Add a third again for 20º.

An iPhone app designed for cinematographers, Helios gives many timings and calculations, including length of shadow as a ratio, 3D views of the sun’s path, a clinometer, and a way of calculating when and where the sun will clear a hill or a building.

Archaeological dig, Kerma, Sudan, 2006

This dig in northern Sudan continued predictably. The variable was the sunlight. I wanted the exact moment at which the sun would clear one of the earthen walls of the site, so that light just caught the archaeologist’s hair and the site plan on which he was writing. This is where timing becomes important.

SOFT SUNLIGHT Manageable Shadows

Some light is simply more useful and less troublesome than others—not necessarily exciting, but certainly practical. Soft sunlight stands at the head of this list. This is sunlight softened by haze, to a degree that takes the edge off its clarity while still remaining what anyone would still call “sunny.” It’s a little like cheesecake—pleasant, but not to die for, and everyone likes it. This is universally attractive lighting that does a good job on most subjects, from people to buildings to landscapes. There’s a reasonable amount of contrast that gives form and shape to things, but the gentleness in the atmosphere keeps the shadows open, their edges softened and the whole scene rounded rather than harsh.

All this makes soft sunlight particularly good for modeling things in a rounded, gentle way, perfect especially for faces. These famous towers that make up the ancient temple of Bayon at Angkor, Cambodia, also carry faces, more than 200 of them. Who they represent is disputed, possibly a Buddhist entity, possibly a king, Jayavarman VII. In any case, on this morning I thought they appeared exquisite, peaceful, and timeless. There was no one else there. I climbed onto another tower and shot.

Bayon, Angkor, Cambodia, 1989

Softened shadows and a hint of warm color.

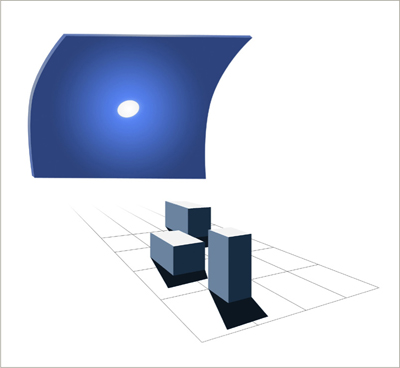

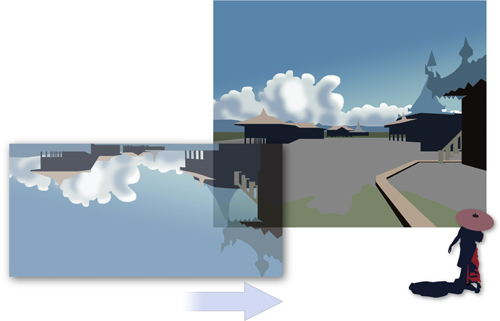

Under hard sunlight

This is how the scene would have looked under normal clear sunlight, the shadows deeper and with hard edges, and the colors more saturated.

Under soft sunlight

In the scene as it was shot, the slight atmosphere—much less than misty—takes the edge off the sunlight, which becomes gentler, with less contrast because the shadows are now more open. The shadow edges are slightly softened also, the colors a little muted, and there is a more definite sense of depth to the entire scene.

The cup of tea glowing in a similar soft sunlight, though later in the day, was taken on the terrace of a tea shop on Rong Hu Lake in Guilin. Tea in China has a much greater significance than its mere appearance suggests, and I wanted to capture the atmosphere of sitting with fresh green tea on a soft day. The shallow depth of field from a very wide aperture helps, but it’s much more about the light. Stronger and more insistent sunlight would have been too sharp.

This is light that works particularly well on commercial assignments, when there’s a planned subject to be photographed and a client to be satisfied, and what makes it particularly useful is its medium contrast range that fits the sensor response nicely. There’s a good distance between highlight and shadow that avoids any sense of flatness, but there’s still unlikely to be any need for shadow fill. It’s also a condition that tends to persist, for hours at least. And because the sunlight is soft rather than intense, it stays more generally acceptable and attractive for longer, even when the sun is higher than you might like it on a really bright day. Again, this is a practical benefit that’s likely to appeal more to photographers who have a specific assignment, often commercial, and who like to plan and guarantee things rather than simply go out and explore. ![]()

Oolong tea, Rong Hu Lake, Guilin, China, 2010

GRAY LIGHT The Beauty of Restraint

Poor gray light. Few people seem to want it. It’s too ordinary, an all-too-predictable condition in mid-latitudes, often persisting day after day to the irritation of people who know that just above that low layer of shapeless cloud (low-level stratus is the culprit), a warm bright sun is shining. Not only does it give a featureless sky, but also it casts no distinct shadows that might at least give form to objects. If there’s a horizon in the view, nothing above the line of hills or row of buildings is of any interest whatsoever. This is truly the orphan of photography’s lighting repertoire.

Well, hang on a minute. Is there really nothing to do with it? Are we just conditioned to find it boring? Maybe instead it’s worth wondering whether we’re overstimulated by impressive light. A glance at the majority of competent landscape images suggests this, as photographers go to great lengths to capture the simply gorgeous—fiery sunsets, shafts of light, rich magentas, and blazing reflections. It’s like the Hudson River School of painting all over again. Don’t worry, we’ll meet all these and more in this book, and high-octane lighting can indeed be spectacularly beautiful, and appropriate. But not all of the time. The word “mood” crops up frequently when photographers talk about light, and how it contributes. A full range of moods includes more than elation, the sublime, and surprise. There are many occasions for moods that are more reflective, quieter, even melancholy. I learned much about this in the few years I spent shooting in Japan, where restraint in many things conveys a kind of pleasure.

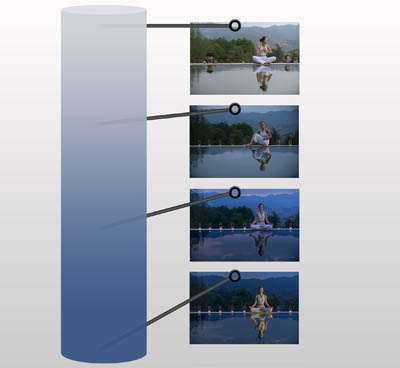

High Court Judge, St Paul’s Cathedral, 1982

Above all, this is sober light that does little to interfere with the subject. It demands, perhaps, a more rigorous approach to composition, especially with placing subjects against backgrounds that contrast because of their natural tones and colors. Colors, interestingly, can benefit from gray light, as we’ll see on the following pages. Both of the pictures here work beautifully in this shadowless light—to my mind, better than they would have in any kind of sunlight (a personal view, naturally). In one, a High Court judge descends the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral in London; in the other, a yoga position on a rock in a still Chinese river. Contemplative light in both cases, you might say. The pair also illustrates an important choice when working with gray light: how light or dark to make the exposure. The contrast in this lighting is low, so there are no benchmarks for brightness. You can see the scene as darker gray or paler gray, and expose and process accordingly. ![]()

Yoga salutation, Beibei, Chongqing, China, 2012

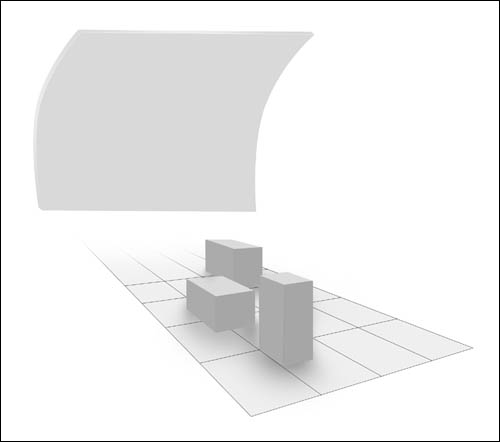

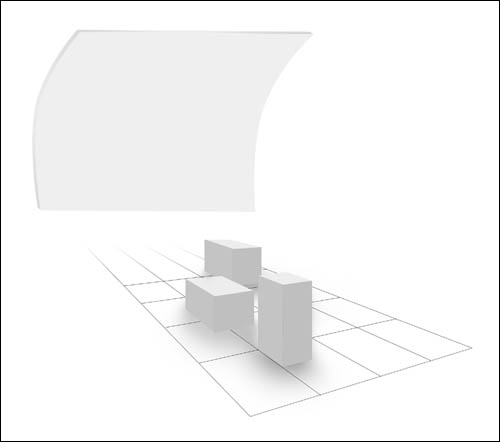

Darker gray

If you treat the overall gray theme as medium-to-dark, the shadow areas tend to come across more forcefully. This is treating gray light as darker-than-normal sunlight.

Paler gray

With the lower overall contrast under gray light there is always a choice of brightness. Overexposing lifts the sense of the image to something lighter and more open.

GRAY LIGHT In the Japanese Garden

In case you weren’t convinced by the previous pages, let me take you through a shoot that might explain some more of gray light’s qualities. I was making a book about Japanese gardens, contemporary gardens in fact, but many of them nevertheless followed traditional principles, or developed on them. There have been a number of styles within the long history of Japanese garden design, but most of them eschewed overt colorfulness. Occasional color certainly exists, which explains cherry-blossom and maple-leaf viewing, both valued for their short seasonality. On the whole, however, bright colors from lots of flowers are considered a bit uncouth, and what is valued is a subtle interplay of greens.

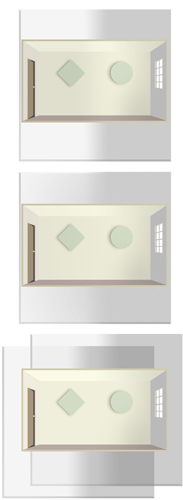

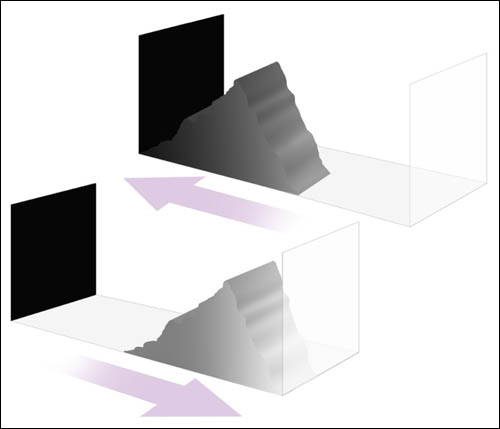

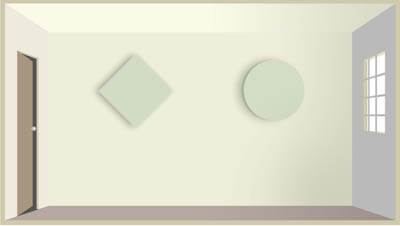

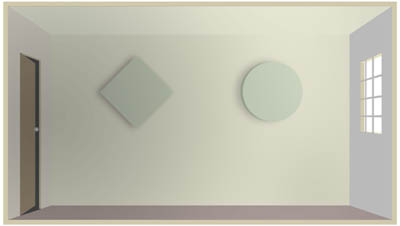

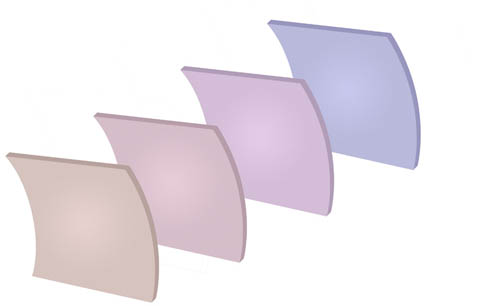

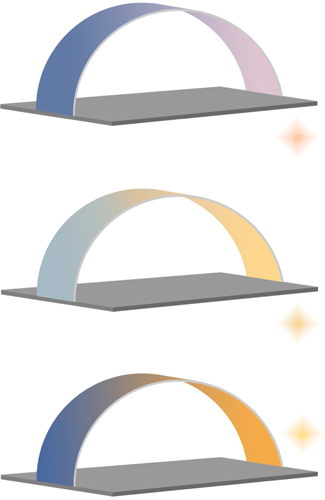

To capture these delicate differences, you have to avoid distractions, and one way of doing this is to avoid the contrast from direct sunlight. Another thing you may have noticed from these and the pictures on the previous pages is that I’ve been careful to frame the shots without any sky. Most skies on gray days have no features, and more than that, they are usually much brighter than the land. The result is that the sky raises the overall contrast, but to no purpose. More than this, however, is the effect of gray light on color saturation, and I learned the lesson quite quickly that Japanese gardens often look their best this way. At least, they tend to look the way that the gardener liked (and gardening in Japan is a fully formed art). The interesting thing here is that if you take a range of colors all from the same group—the same sector of the color circle—they appear at their best saturation when the lighting is even and gentle, not bright and contrasty. This seems counterintuitive, but it’s because flat light does away with bright highlights and sharp, dark shadows, neither of which have much color at all. Look at the two illustrations. The hues are the same, but the lighting is different. The sunlit version catches attention because of its contrast, but the saturation in the other one is actually stronger by a quarter. ![]()

Ichijo-in temple garden, Koya-san, Japan, 1996

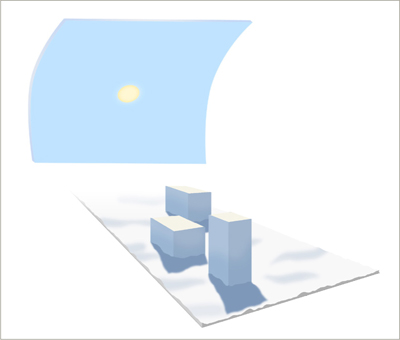

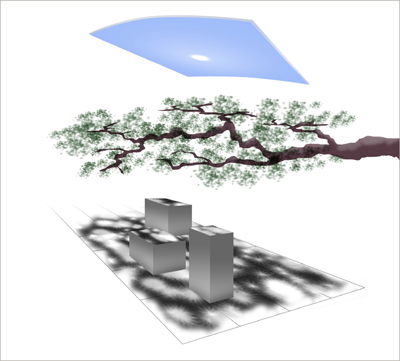

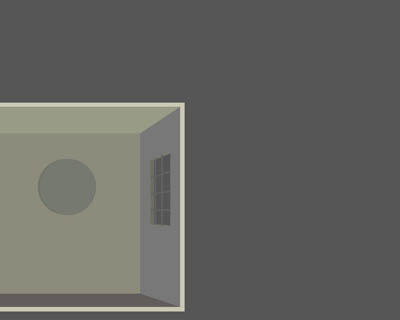

The illusion of richer color

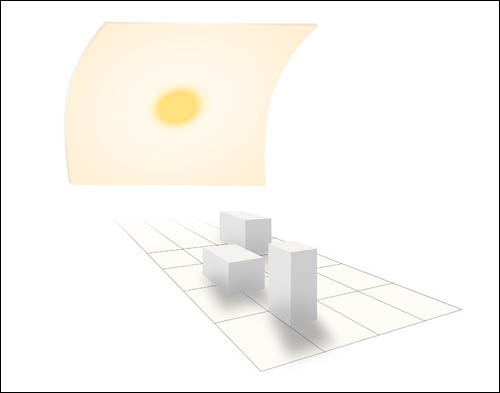

In sunlight, the higher contrast gives a sense of colors being rich, but this is an illusion, albeit an effective one. In this illustration, the greens are actually 25% less saturated than those on the next illustration.

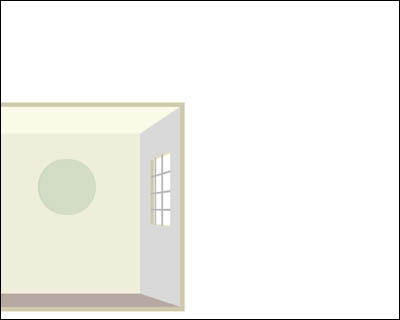

Deeper saturation in flat light

In gray light, without shadows or edges, the same colors are better saturated, by 25%.

Rich greens

Pillow-like Japanese topiary, also on Koya-san, looks well modeled and rich in color under the same light.

Green variety

More gray light and a detail of another Japanese garden, this time featuring a deliberate variety of green hues, which extends to the specially selected pebbles.

SOFT GRAY LIGHT On West Lake

Key Points

Soft

Melancholy

Low Contrast

One of the secrets of photographing the gardens on the previous pages was to frame the shot so that no sky appeared. A wedge or bar of sky would take the contrast of the scene completely out of range. If you include sky, or as in this case here, its reflection in water, you have to deal with the exposure in a different way. This is West Lake in Hangzhou, China. Along with the renowned Dragon Well tea from the surrounding hills, and a history of cultured learning, this lake is what Hangzhou is famous for, and it has served as inspiration for poets, philosophers, and artists for centuries. You walk along the lake paths, or take a small boat, or simply sit and look. With thousands of other people unfortunately, if it’s a weekend (this is where photography’s ability to turn off the sound is a positive advantage). I had my usual ideas about how lakes can be captured, which in the past have generally involved low sunlight from one direction or another. But on this day in May, sunlight was West Lake, Hangzhou, 2012 unlikely, and my first reaction was some disappointment, though my friends who live here said that this is exactly what to expect—Hangzhou is also famous for rain.

West Lake, Hangzhou, 2012

So, what to do with West Lake on a gray day? The answer was to learn a little bit more about its place in Chinese culture, and what better way than the poets themselves? Here are the opening lines from a series of poems written by Ouyang Xiu in the eleventh century (there are some very different sounding English translations because the combination of characters is open to interpretation):

A light boat with short oars—West Lake is good.

A gentle curve in the green water

Deep in spring, the rain’s passed—West Lake is good.

A hundred grasses vie in beauty

Who can explain why we love it—West Lake is good.

The beautiful scene is without time

I read other poems and picked out lines and phrases that evoked a similar mood:

Fine mist on distant water,

One white egret flying from the Immortal Isle

Misty mountains shrouded the rain

In the shade of the green willows

The blur of color across the hills is richer still in rain

The direction was plain. Gray cloud and still water, green willows, a small boat, a bird, and above all, soft. Little pleasure boats still operate, and all that remained was to find the right, simple combination, keep bright colors out of the frame, and enjoy the gray. ![]()

West Lake, Hangzhou, 2012

Other versions of the same scene, trying to capture the traditional appeal of West Lake.

Because of the lower contrast in gray light, the tones do not fill the width of histogram from black to white. As a result, you can choose where to place them, darker (as here), or brighter.

DARK GRAY LIGHT Wild Weather

Iceland is one of the truly wild and strange landscapes in the world. In fact, most of it is landscape, because with a population of just over 300,000 and a capital city that feels like a small town, the feeling of traveling around the island is distinctly primordial. Even sheep are thin on the ground. This has often attracted filmmakers, particularly when the film has a science-fiction theme, though they tend to founder on the number of bad-weather days. One film that made a virtue of this was the recent Prometheus by Ridley Scott, and here is the wild waterfall that opens the movie. Typically, the weather had changed totally in several hours; the day before had been cloudless and had also been the longest day of the year, with a 24-hour midsummer sun here in the north. Now there was a looming dark sky, which suited this landscape very well, and made it look distinctly otherworldly.

It also raises an interesting question with this kind of low-contrast light. How dark is a gray sky? No, it’s not a Zen koan; it does have an answer. The idea of normal brightness for any kind of scene revolves around the idea of a mid-tone—something we take for granted in photography. It’s the principle behind the camera’s metering system, and indeed behind all the ways of presenting images, in print and on screen. An average mid-tone is the benchmark, and if you decide to go higher or lower, it’s for a purpose, generally that of mood. Gray days are no exception, but they are easier to see and experience on a scale of brightness. Once you get used to the idea of gray light, you find that it comes in different shades. There are paler grays and heavier grays, and because the contrast is lower than in bright sunlight, there is room for interpretation. As the histograms show, you can expose higher or lower with impunity. Within a range of a couple of stops, the scene will stay within the sensor’s dynamic range, but it will look and feel different—and the feeling is what it’s all about.

Icelandic waterfall, 1987

So who decides? Certainly not the camera. Given the flexibility you have in exposing, and later in processing, the only sensible way to judge is to rely on your impression at the time. And yes, this can be influenced by things other than just the physical light—the scene, the subject, your mood, some idea you might have. Shooting in gray light with low contrast is technically easy (it’s difficult to expose out of range) and that makes it important to think about the feeling of the scene at the time of shooting, and even more, to remember it. ![]()

Very dark gray

Normally our eyes simply adjust to the level of gray brightness, but with the lighting situations shown here, the sensation is distinctly darker than average.

Port-Eynon Bay, 1980

SHIFTING THE HISTOGRAM LEFT

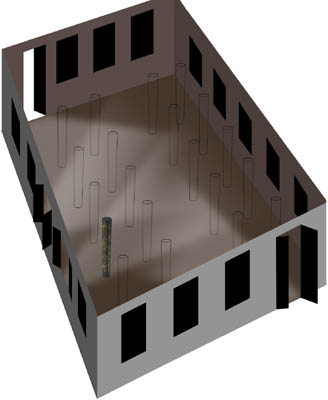

A low-contrast subject under diffuse gray lighting always gives a processing choice, as the histogram does not fill the scale. Shifting it left until the darkest tone becomes black makes the most of dark gray light.

WET GRAY LIGHT Falling Rain

One of the things about flat gray days is that they often lead seamlessly to rain. And rain has a bad reputation in photography, though it’s not entirely deserved. For a start, most people find it uncomfortable, and photographers instantly feel the need to protect expensive gear from it, so it’s generally a much easier option to avoid it and put your feet up. Drops get on the lens and have to be wiped off constantly, the humidity causes condensation on internal glass surfaces like the eyepiece and lens filter, and the camera body itself can take only so much. And even so, the light is still gray. If you’re wondering what the difference is between gray light on the previous pages and this, the answer is something like a glistening, or slicked effect. If gray light suits green plant life, vegetation positively basks in rain. The water adds a sheen to leaves that lifts the local (very local) contrast in a special way that gives a subtle sharpness. Rain also does other good things, such as adding raindrops to glass surfaces and rings to water. Generally, people don’t like getting wet in rain, but they do respond to its soft melancholy, as long as they’re dry while they watch it—as if it were already a photograph.

Backwaters, Pattanakkad, Kerala, 1981

Falling rain is actually less visible in a still photograph than many people think, and certainly less than in a video. The vertical streaks have a habit of blending into what looks like a kind of mist, and to stand out, the rain needs to be heavy, or the lighting bright, enough to highlight them (see Rain Light—Shower in a Sculpture Park on pages 162–163). What usually helps the atmosphere is the collection of side effects, like umbrellas and drops bouncing off the ground.

I had an assignment once, early on in my career, to photograph the coastline of Kerala in southern India for the Sunday Times Magazine. The shoot was scheduled for late October, which should have been fine, but that year the monsoon was late, and we had unremitting rain for a week. I wanted “good” light, but had to put up with this, which I found annoying; but really, that was a rather childish reaction. Of course it wasn’t comfortable—everything was sodden, including me—but that was the point, if I had only realized at the time. If you get too locked into the idea of “good” light being golden hour, you also start to associate rewarding photography with pleasant, holiday-style weather. In reality, they’re not perfectly matched. I ended up with many good shots from that week, but appreciated them only later. Another lesson learned. ![]()

Light in falling rain

For rain to be visible, it usually has to be heavy, and contrasting in some way with the background. Backlighting helps. Overall, it has an almost misty effect.

Cambodian girl in rain, Phnom Penh, 1989

The more you look into all this wetness and grayness, the more variations you discover, and if you’re prepared to enjoy the subtleties, there’s a surprising amount to explore in terms of viewpoint, tone, color, depth, and more. In a valley north of Chongqing is an old Buddhist monastery on a forested slope among natural hot springs. I was working for a client who had a high-end resort property close to the monastery, and early in the morning, before breakfast, I went for a walk in very light drizzle. Just a few occasional small drops, not enough to shelter from, but the grounds of the temple were laden with a soft, damp atmosphere that seemed to dampen sounds. I passed this old drum tower, on a lower level because of the slope, and thought how perfect it would be if someone just happened to walk by, giving a kind of purpose to the gray flaring roof and an air of abandonment. No one did, even though I waited a while. The best action that happened was a monk and some women sweeping the grounds and clearing a pond, which didn’t really do it for me (opposite, top).

Tai chi, Wen Quan Buddhist Temple, Beibei, Chongqing, China, 2012

After a quarter of an hour, some activity.

But a little later, I found that I had a shot to do for my client—a tai chi demonstration by a visiting kung-fu master (opposite). Well, I had the perfect location. He would be wearing white, for which this dark and delicate background was as perfect as if it had been a stage set. I filmed the subject also, and in the video the light drizzle is just visible, adding a little bit more mood. Above all, what works in the lighting is the very slight aerial perspective as the drizzle adds a layer of substance to the air. This gently helps the man stand forward from the temple building, and the temple building from the trees behind. It also suffuses everything with a muting effect that reduces color. As with all of these gray scenes, the low contrast makes it important to decide how dark or light the gray should be. I was mainly concerned with keeping a good, but not overdone, contrast between the man and the parts of the building under the spreading eaves. Overall, I went for a slightly darker result than average. Practically, what I did was to shoot according to the meter, which was set to matrix metering, then reduced Whites and Shadows a little during processing. ![]()

The temple drum tower, early morning

The scene as I came across it, with no people, an hour earlier.

WET GRAY LIGHT Glistening Stones

When the rain stops, it leaves behind yet another slightly different variety of gray light. Often the air is clearer, and the wetness gives a fresh feeling to the scene. Unless there’s more rain on the way soon, it’s a situation that doesn’t last as long as you might think, as evaporation starts quite quickly. In warm weather, the water will start to dry off surfaces well within the hour; and in the tropics, in the monsoon season, even faster than that. Another thing that affects shooting is that rain tends to clear other people out of the scene—very useful if you’re shooting in a site populated by tourists, as with Angkor in this picture. When it stops, they slowly reappear, along with muddy footprints.

Ta Prohm, Angkor, Cambodia, 2002

It’s interesting that you need only a few visual clues, like the glistening surfaces of stones in the shot of Angkor opposite, or the unbelievably costly stone in a Japanese artist’s garden (right), to turn the perception of plain gray light into its wet version. Just a hint of something slicked with water, tucked away in the image, and suddenly the mood has changed. As before, wet weather is lovely to look at, all the more so when you’re not standing in it.

The picture of the semi-ruined temple of Ta Prohm in Angkor was shot in the rainy season, making a refreshing change from all the other times I had been there, which had always been in the cool dry season when the sunlight is guaranteed. This monsoon shoot had a lot going for it, not least the greenery and the moss. There were also fewer people around, which suited me. My first visits to Angkor were during the civil war and there were truly no other foreigners at all, so I became a little spoiled. This, though, was exactly what I wanted: early morning after rain, no tourists, even the muddy ground freshened overnight, and the old caretaker working on a few fallen leaves.

The Japanese garden on the right belonged to a painter, and this was the view from his studio, looking out to the costliest stone I ever came across. In the Japanese tradition of paying great attention to rocks and stones, which goes back to at least the sixteenth century, this artist, Akira Kaho, had had his eye on one special stone for two decades before he could afford to buy it at a staggering twenty million yen (about $10,000). Called a sajiishi, it is unique, with a flat top eroded into a complex of deep runnels, as if some strange worms had tunneled into it. Most stones look their best when wet, and this one certainly deserved special treatment. ![]()

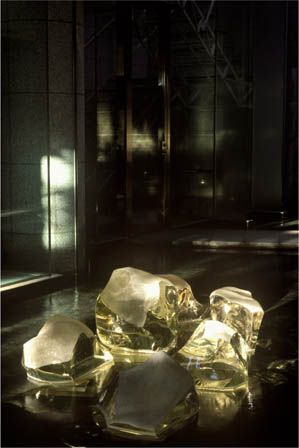

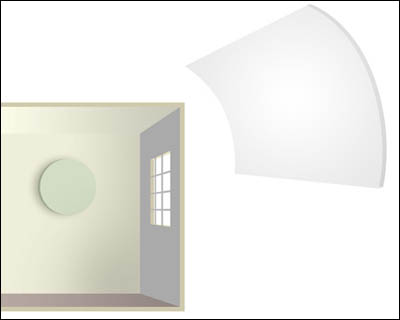

Wet gray light

Reflections in flat wet surfaces, while top surfaces reflect light from the sky, givng a glistening effect and higher local contrast.

Painters’ Stone, Kyoto, 2001

HARD LIGHT Graphic Geometry

After gray light, the most commonly rejected and unloved is the hard-edged light from a high sun. You’ll find more advice published about how to avoid it than how to use it. There’s little mystery about hard light, and this is one of the reasons why it often gets thought of as un-special, unkind to subjects, and even downright ugly. The “hard” refers to the shadows that it casts, because the source is a bright sun in a clear sky, with little of the filtering effect from atmosphere that characterizes soft sunlight. The result is dense shadows with hard edges, and inevitably high contrast.

Here we’re back to likeability, and the attractiveness index of hard light is rated low by most photographers—hence its name, and the common refrain, “the light’s too hard.” The reasons given include poor modeling (true), high contrast with blocked-up shadows (yes, if you need them open), and coming from above, so that it casts shadows in strange places on people’s bodies and faces (without a doubt). Technically, then, it’s problematic if you’re trying to make people look attractive, when you’ll need a lot of help in the form of filling, shading, or diffusing (see Section 3—Helping).

Greenberg House, Los Angeles, 1994

Hard light

The intensity of this hard light creates denser shadows, which play a greater part than usual in photographs.

Normal sunlight

Standard sunlight gives reasonably strong contrast and hard edges to shadows, but not to the extent of the lighting in the Greenberg House image shown opposite.

However, this apart, the reputation of hard light may be overdone. When it comes to, say, the raking light of the following pages, where hard shadows and intense sunlight can pick out details and texture in a highly tactile way, it becomes desirable. And at the ends of the day, during golden hour (see below), the intensity of rich, warm sunlight set off against deep shadows gets many landscape photographers excited, particularly those shooting in stark landscapes like the Arizona desert. What hard light does have going for it is hard shadows and an intensity that, with a suitable subject, can deliver a degree of abstraction. Abstract imagery is a move away from the real, turning a scene into something else, at least until the viewer’s eye has settled down to seeing what is really going on.

Geometrical abstraction is arguably what hard light does best, and it’s no coincidence that my example here is a Los Angeles house by the renowned architect Ricardo Legorreta, not the first or last Mexican architect to design specifically for the cloudless skies of southern California and northern Mexico. Everything here is straight-line sculptural and hard-edged, and specifically created to be overlaid with shadows and enhanced by contrast. ![]()

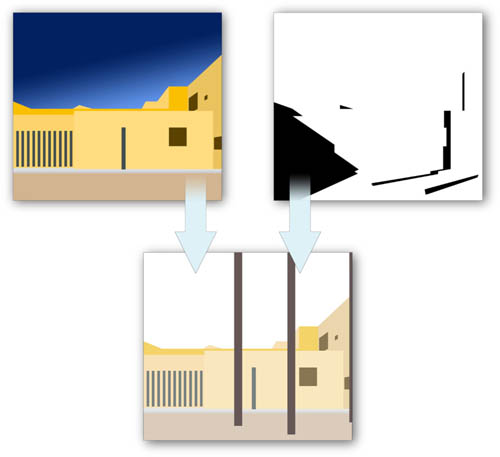

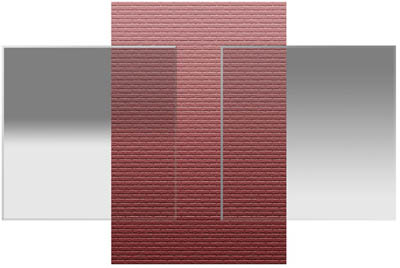

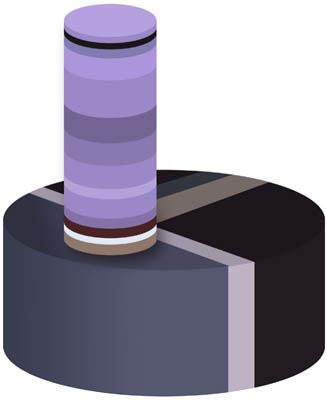

SEPARATING COLOR CONTRAST & SHADOWS

The total deliberate effect comes from combining the rectilinear geometry of the structure (below) with strong colors (top left, one of these from the Southern Californian sky), and hard-edged shadow shapes (top right).

We can go further with the idea of hard light suiting hard-edged subjects. Largely because of portraiture, where the aim is usually (though thankfully not always) to make people look attractive, the idea of soft, directional light to give gentle, rounded form gets a lot of promotion. Yet angular objects tend to do better with lighting that shows off their hard edges and contrasting surfaces. Lighting angle becomes more critical when there is no diffusion, but when it’s right for the subject, the effect is strong and eye-catching.

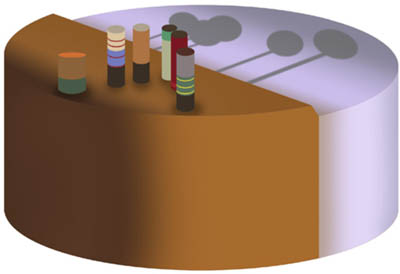

There is a street in the Burmese city of Mandalay, just one street, where the entire activity is the carving of statues of the Buddha from local white marble. The demand for these across Myanmar is considerable, so it’s a busy place, and the statues are in all stages of production in the small workshops lining the street. Because of the weather (hot), these are open with awnings, but stones that are waiting for attention are more usually out in the tropical sun. The combination of white marble and a high Burmese sun makes for extreme brightness, and so this is really pushing the limits of contrast. Again, a choice: return for a lower sun, or do something with these midday extremes? If the latter, why not take the extreme and push it further? We’re back to graphic imagery, for which hard light can definitely do favors. Besides, there were these blocky, faceless statues waiting for the sculptor (labor is divided here, with the top craftsmen concentrating on the more demanding face of the Buddha).

Faceless Buddhas, Mandalay, Myanmar, 2008

The setting

Midday in Mandalay, with a group of Buddha statues waiting for the master carver to start on their faces.

At this time of day, the sun is pounding down across vertical surfaces—raking light, as we’ll see shortly—and that was putting a lot of attention onto the yet-to-be-carved face blocks. One option was to shoot for black and white, which for the reasons explained on the following pages, makes it easier to process for extreme contrast. The fairly simple division between just dark and light, with very little intermediate shading, thanks to the hard light, made it possible to take the contrast in the final image very high. The shadows could go to perfect black, and the white marble simply had to remain a couple of levels below knock-out white. ![]()

As exposed, without processing, and in color.

Processed for maximum visibility

The Raw file opened up to the full—more information, much less impact.

Processed for maximum contrast

Going even further than the main picture with the high-contrast processing, emphasizing the cast shadows.

HARD LIGHT The Case for Black & White

Key Points

Monochrome

Texture

Tonal control

Black and white has its own particular aesthetic, quite different in many ways from shooting in color. For example, tonal gradations—from richness to nuance—are an important part of it, as the image is free from the distractions of color. But among the special values of black and white, two of them make it a very useful solution for lighting issues such as hard light. If you’re a die-hard black-and-white photographer, this will not impress, but for anyone who shoots mainly in color yet is prepared to experiment, this is one way of turning disappointing conditions into strong imagery.

Yak caravan, Manigange, Sichuan, 2009

The first of these two reasons is that black and white is, if not exactly immune to the time of day, much less restricted by it than color photography. Just look at the many lighting situations in this book that are located in the golden and magic hours. Probably the strongest component of these two very popular times of day is their color, and because so many photographers prize these end-of-the-day hues, by comparison midday tends to be ignored. Black and white does not suffer from this problem (if you consider it a problem; not everyone does). The second reason is that you can push the tones to extremes much more acceptably in black and white, so a hard, contrasty treatment that might look unpleasant in color can look great in monochrome.

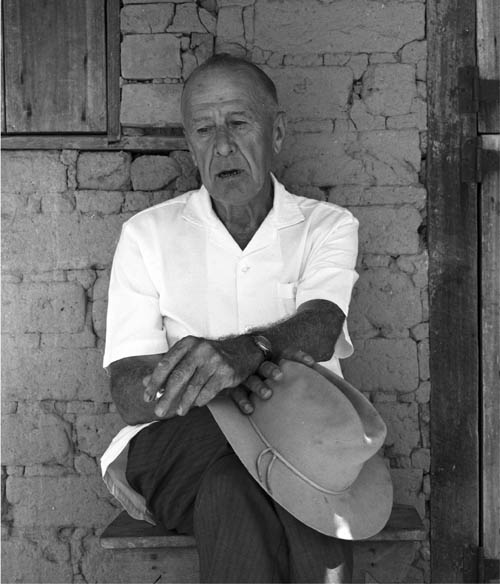

This shot (left) of Tibetans loading up a yak caravan for the trail used both of these black-and-white special values. It was midday in western Sichuan, at high altitude and clear, so the light was stark and the colors of the riverbed where they were camped were bland and uninteresting. They weren’t going to wait for late afternoon and good light just for me, so I just had to get on with it, as usual. I quickly decided to switch my mind to black-and-white mode, and concentrate on tonality and shape. There was one tone in particular that I focused on—the leathery face of this man. Leathery is a cliché, of course, but here was a case where it was completely justified, not just because his skin was so weather-beaten, but also because of the comparison with the leather sacks they were loading. For my purposes this was wonderful—here was a yak caravan in the 21st century using traditional leather sacks, not plastic. The general lack of color made it less easy to pull off in post, but I managed to do what I wanted and use B&W conversion to get that face dark and rich. ![]()

A choice of conversions

A range of conversion options, though not extreme because of the lack of intense colors to begin with (black and white conversion works more powerfully on strong hues).

As a color image, for me weakened by the insipid colors and hard top-lighting.

An alternate take on a B&W conversion, aiming to deliver maximum information—and as a result, little more than a monochrome version of the color default.

The Raw file, unprocessed

In itself, acceptable as a color image, but the monochrome tint brings little to the image, suggesting a B&W conversion so as to allow concentration on the tonal nuances.

Darker alternative

Even with an apparently monochrome-yellowish original, B&W conversion by channels allows tonal values to be altered, as here, to a darker, denser version.

Water buffalo, Yalong River, Sichuan, 2009

HARD LIGHT Stark City Contrast

Key Points

Unflattering Light

Juxtaposition

Key Shots

There’s a reason for the order in which I’ve started this book, even though it might at first look a bit haphazard. The first entry, on soft sunlight, is a perennial favorite and unassailably pleasant, but I followed this with an opposite gray light. Now, with hard light, we have another group of normally rejected candidates. This is all aimed at undermining the idea that a good use of lighting is always in the service of being conventionally attractive. Mainly, perhaps, but to aim for it every time is highly questionable. More than that, it simply limits the range of what you can do.

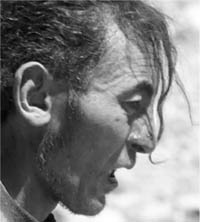

Temple of Olympian Zeus, Athens, 1977

As we just saw, one of the many things that lighting can do is to help evoke the physical sensation of a place and a time. It doesn’t necessarily matter that the location may not itself be conventionally attractive. Here in Athens, though, there was something else again—I had a specific job to do. This was to be a book in a big Time-Life series called Great Cities, and the editors had made an interesting choice of approach. As much as any high-volume publishing to a wide audience can tolerate, there was a negative undercurrent running through the book. This was not to be the Athens of tourist brochures, but instead a more complicated city that had grown to be quite ugly and polluted. This ran through the text, and the choice of pictures reflected it. The editors wanted this to be an interesting book rather than just a pretty one. A particular issue was how to deal with the many famous ancient monuments. Naturally, I shot around them over the month of shooting in every way possible—including every kind of light from before dawn to dusk—yet always knowing that the editors needed an edge to it all. With so many existing beautiful images of the Acropolis, for example, it wasn’t really Time-Life’s job to add to the store. Accordingly, the monuments photo essay was conceived as an aerial, using a helicopter to show these ancient sites crowded by the spread of cheap building that makes up the modern city.

This theme turned out to be the choice for the cover, also. It meant, inevitably, a juxtaposition shot, and almost as inevitably a telephoto treatment to compress contrasting elements. The best candidate for this turned out to be the Olympeion, also known as the Temple of Olympian Zeus: 2nd-century marble columns set against a 1970s apartment block. It had the added advantage of being graphic—verticals against horizontals. What light would work best? A pretty end-of-day, or something starker and more in keeping with the idea?

I used a similar setup for the forlorn traffic junction on the right, which is not, as you may suspect, the scene of recent heavy shelling, but yet another Chinese city block in the process of redevelopment. ![]()

Athens cover

The picture as used.

The aerial view

Part of a photo essay in the book, the aerial view shows the monument far from impressive, hemmed in by a busy, ugly city.

Demolished city block, Ninghai, Zhejiang, 2011

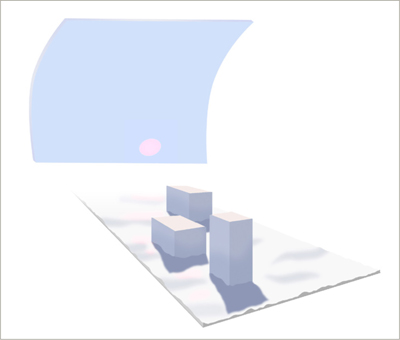

Key Points

Minimum Relief

Stress Absence

Minimalism

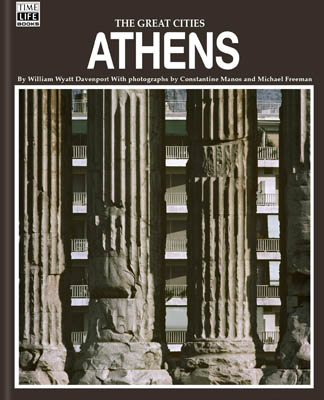

Here is another case of looking for a way to get across the physical sensation of a place—a strange place, and one of the emptiest I’ve ever been in. To be honest, the “flat” part of this light refers more to the land that it’s falling on, but the result is certainly that. No relief to speak of, and at the time we drove across it, the sun was almost overhead with not a hint of cloud. This is in the Nubian Desert of northern Sudan, and the country is mainly desert in any case. Even within deserts (which qualify as such if they have a moisture deficit, normally taken to mean less than 10 inches [25cm] of rainfall a year) there are extremes, and this is one such. This section, called the Bayuda Desert, is exceptional in flatness and lifelessness. I wanted to get both of these qualities across, and the way to do it seemed to include just a touch of their opposites. I should explain this thinking: It’s a quintessentially minimal situation, with land and sky reduced to two bands. One approach would be to present this minimally, choosing a view that had no relief at all and no life. This was an available option at the time, as we had our Land Cruisers and I could select anywhere to shoot as we drove, hour after hour. It would also be a valid choice, and for the marine equivalent see Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographs of seascapes.

But I chose the other way, which is to try and stress the featurelessness by means of contrast, namely by including a hint of relief and of life. Eventually we passed this spot, with an extremely isolated bush and two swellings of sand beyond. The remaining element in the photographic mix was the light, and here I was happy that it was so stark, and, well, flat. Now, deserts look excellent in raking light at either end of the day, and that is definitely the picturesque approach: sand dunes casting sinuous shadows and ripples standing out in the foreground. But deserts definitely look hotter and emptier—more desert-like to my mind—under flat, high, midday light like this. ![]()

Bayud Desert, northern Sudan, 2004

Stitched assembly

The shot was given higher resolution by taking a panorama of overlapping frames.

High sun, no relief

The combination of a near-overhead sun and almost nothing on the ground to cast shadows gives a flatness in keeping with the essence of this bleak desert.

An alternative

A second shot without the bush: emptier, but lacking the contrast that the isolated bush gives.

Key Points

Lunar Quality

Sky Blue to Violet

Polarize

The higher you go, the less atmosphere there is, and so the more intense the sunlight. For most people, altitudes over about 2 miles (3km) are unfamiliar, and that alone makes this kind of shooting location interesting. The examples here are from western Tibet, higher than Lhasa and the east, and where the base of the plateau is at around 3 miles (5km). There’s a simple correlation for this kind of locale: at 5,000 meters the oxygen pressure is 50% of that at sea level. Apart from breathlessness, the other effect is that sunlight is a little bit more like it is on the Moon—unremittingly hard, giving a massive dynamic range.

Bear in mind, though, that dynamic range matters only if you want to recover all the details in the shadows and highlights. And why would anyone want to do that in this special environment? What makes the Tibetan plateau here so special is exactly this hardness of light, which you can find only at altitude. In other words, this is not a problematic lighting situation, but rather one that is worth exploring for its rarity. The only pity is that a photograph cannot get across the genuinely disorienting, dreamlike sensation of not being able to breathe properly. But at least it can preserve the lunar quality of the sunlight, and way to make the most of this is to look for subjects and arrangements that are themselves contrasty: white prayer flags shot from low so as to place them against the darker sky overhead, dense shadows, snow on the south face of Mount Kailash against the sky, and so on.

Prayer flags over a chorten, Nara Pass, western Tibet, 1997

High-altitude hard Light

The contrast between light and shade is as high as it gets anywhere, and open shade is noticeably blue.

All this blue is a reminder of the very high UV content of the light, or rather the failure of the thin atmosphere to block it. How you deal with it is a matter of preference. You could simply go for it and use the blues, or make it more realistic by fitting a strong UV filter and/or taking some of the blue out in processing. Yet another approach is to us a polarizing filter to push the already-deep blue sky into an even deeper violet. High altitude encourages exaggeration, which is no bad thing. ![]()

Mount Kailash, western Tibet, 1997

POLARIZING FILTER AT ALTITUDE

The darkening effect of a polarizing filter on a blue sky is strongest at right angles to the sun, and at these altitudes, is stronger than usual.

RAKING LIGHT Façades

Light can also be a collaboration between the sun and the surface, and the idea of raking light is when the source is sharp and pinpoint (like the sun on a clear day) and glancing across a surface that has some kind of delicate relief. When we come to bas-reliefs on the following pages, the relief effect that the carvers and artists intended under cross light was deliberate, but there are many more situations when it just happens to be. Here are two such cases, and in both, the façades were designed in one way, but photographed in another.

Football, Cathedral, Cartagena, 2009

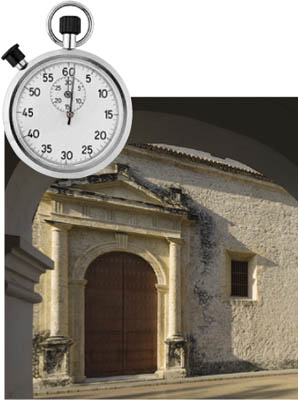

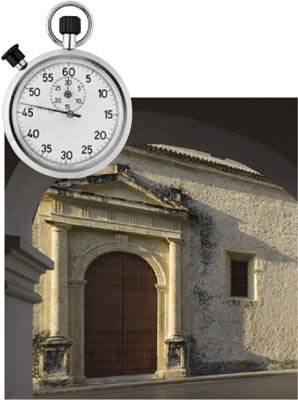

Religious buildings, like the cathedral on the left, are often aligned to the cardinal points, which naturally means that one of the sides tends to be side-on to the early and late sun. That was exactly the case here, in Cartagena, and very predictable in February, when the skies are usually clear and the sun rises and sets not quite so much toward the south as in the rest of the year. This was indeed a planned shot, for Sony, who commissioned a number of photographers to shoot pictures of football (soccer) being played around the world. With this brief, it was obvious that the setting and players were going to be important—more so than the ball itself. In particular, this was because the readers of the book would already know the subject and be looking for the variations on a theme. I needed to step back, and so needed a background that located us firmly in the colonial era of the Americas, without being cheesily obvious. The south side of Cartagena Cathedral (left) seemed good to me, especially as there was a plaza across which I could shoot without having to angle the camera steeply upward—in the end I didn’t want converging verticals, and there would need to be some Photoshop perspective adjustment.

Raking light does two important things to a wall like this—and to that of the old Mexican mansion in Mérida also (right). It reveals texture, and it adds the shapes of shadows. These are actually two quite different things. The texture enhancement simply shows more of what the subject is about—in the case of the cathedral, the coral limestone blocks and the way that the portico projects. The shadow shapes are purely graphic additions, overlaid on the rest of the image. Together, both breathe life into the wall. And a final thing, those raking shadows are very narrow, front to back, so that I could place the boys just a few feet in front and have them side-lit, standing out against the shadows, and considering that I wanted the two players small against the huge cathedral, doing this ensured they caught the eye. ![]()

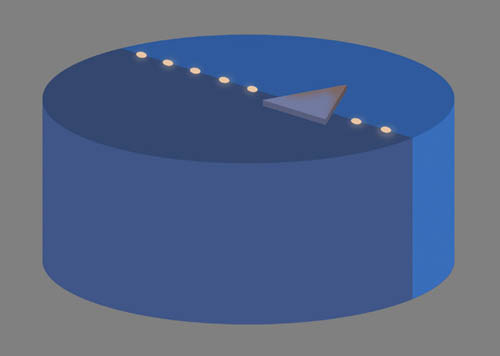

Shadow movement over three hours

Over a period of nearly three hours, from 3:38pm to 6:12pm, this is how the shadows lengthened and moved across the south wall of Cartagena cathedral. The atmosphere was slightly hazy, with the result that the shadows weaken as the sun approaches the horizon. Only on crystal clear days do they stay sharp and solid until the end (see Golden Hour—Last Moments pages 100–101).

Mansion, Mérida, Yucatán, 1993

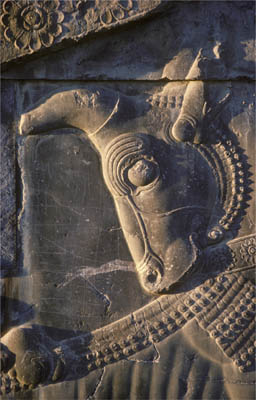

RAKING LIGHT Perfect for Bas-reliefs

Key Points

Sculpture

Appears Deeper

Keep Hard

I don’t like getting locked into one kind of light for one kind of subject, as seems to happen, for example, with a lot of contemporary landscape photography. There’s nearly always a choice of interpretation, as I’m showing throughout this book. Bas-reliefs, however, are very much made to be seen under a light that shows their details, and that really does mean raking side-lighting of one kind or another. The term means low relief, carvings, or moldings that just stand out from the surface. Deep relief is almost sculpture, where you can put your fingers into and behind some of the carvings; bas-relief works more subtly. It needs the help of lighting to do it justice—lighting from an acute angle, ideally just grazing the surface.

Here are two ancient sites famous for the excellence of their bas-reliefs: Angkor in Cambodia (right) and Persepolis in Iran (opposite). In both, the stone carvers certainly knew what they were doing, and what effect the light would have. The Persian bas-relief starts to come alive in the late afternoon, particularly in winter, as the entire complex is aligned northwest-southeast, so that with the sun setting north of west, this southwest-facing wall catches the grazing light. The Angkor carving of a devata (minor goddess) is a little different. It likewise catches late afternoon light—and early morning, too, as it is on a south-facing wall—but it also catches midday light. It was vandalized, probably during the Khmer Rouge years, as the face has been hacked into rather than removed, which thieves would have done, and I was looking to include this kind of damage for a story. The hardness of the sunlight, and its direction from above, gives a stark treatment that makes the most of the hacked-away face, leaving a deep black slash. In a way, I’m doing much the same thing here as with the marble sculptures on pages 30–31.

Vandalized devata, Thommanon, Angkor, 1989

In both cases, light coming in from the side exaggerates the relief visually. Both carvings seem to stand forward much more than they really do, and compared with how they look in flatter lighting at other times, the effect is a kind of illusion. There would be almost no point in filling in shadows with a reflector (see Filled Light—Tai Chi in a Tea Garden pages 206–207); that would just weaken the relief. Moreover, as this is the sun rather than flash or any other kind of photographic lighting, its distance means there is no fall-off (see Window Light—Classic Fall-off pages 86–87) across a carved wall, even a large one like the smaller image below of the Bayon in Angkor. If you want a choice of lighting, and the sky is clear, wait until the sun is close to the horizon and the effect begins to disappear (see Golden Hour—Last Moments, pages 100–101). ![]()

The Khmer army, Bayon, Angkor 1990

Bull in bas-relief, Persepolis, Iran, 1977

High raking light on a south-facing wall

The effect of top raking light as in the image of the devata at Angkor. With the sun high (tropical light), it moves quickly, and for just a very short time, rakes the wall from above.

RAKING LIGHT Sharpening the Landscape

Then, of course, there’s raking light bathing the entire landscape. It’s also light from the golden hour, inevitably, because unlike the walls we’ve been looking at, there are only two times of day in most latitudes when this happens: early morning and late afternoon. Nearer the Arctic and Antarctic, on the other hand, the time for this light spreads out across the day. This type of lighting is naturally attractive and popular because of the way in which it sends long bands of light and shade across the landscape. I argued against the grain in Hard Light—Nubian Desert on pages 36–37, but that was for a very specific reason (showing emptiness). As I mentioned then, the raking light that throws up every ripple in sand is more conventionally appealing.

Polo pony, Gran Sabana near Bogotá, Colombia, 2011

In common with the other, smaller-scale raking light situations, it depends not just on the sun being low, but also on there being really clear air. As the sun gets lower, its light has to pass through much more atmosphere than when it is shining straight down onto the land, and this acts like a softening filter. On top of this, haze and pollution tend to hug the ground, so that those last few degrees of the sun above the horizon often—I could say usually—see a rapid softening of shadow edges. In practice, it means that what looked like a bright day an hour before sunset unexpectedly becomes almost shadowless three-quarters of an hour later. The lesson learned is not to expect the crisp light to last for a moment longer than you can see it, even though hanging on until the last minute is what most of us do in these conditions. The answer is to keep shooting, because the frame you just shot may well turn out to be your best.

The main shot is from the high savannah surrounding Bogotá, where the air is usually clearer because of the altitude, nearly 9,000 feet (2600m). I’ve also included a shot from the Tibetan plateau at over 16,000 feet (5000m), because at this height the air is thinner, so the light is sharper, more incisive, with little of the haze that’s normal elsewhere. The effect is that the same sharp shadows continue to the horizon, which can be breathtaking. Clarity covers the entire view, so that while we know from common sense that the farthest shore of the lake is really distant (a few miles), it looks as if we could reach out and touch it. I think it is this contradiction that makes lunar views like this one interesting. ![]()

Lake Manasarovar, western Tibet, 1997

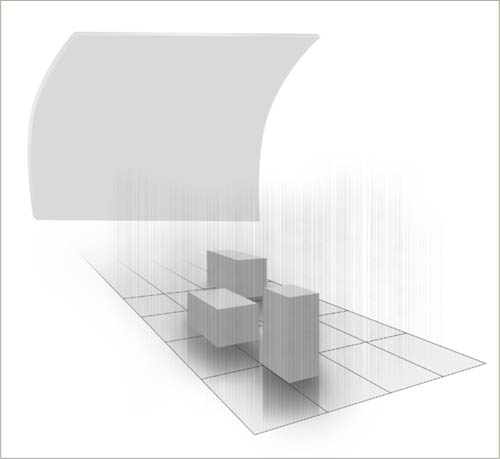

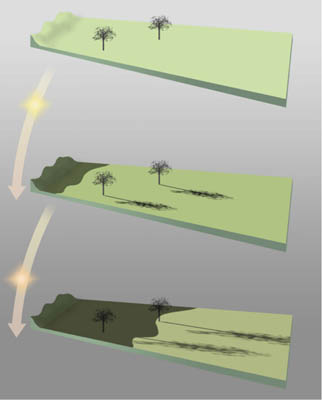

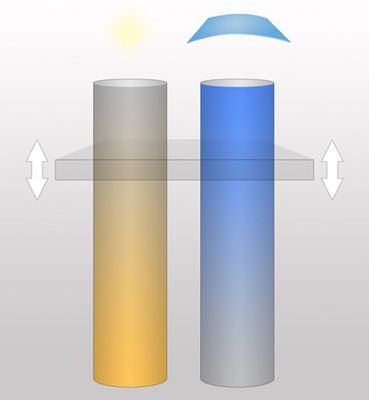

SHADOWS LENGTHEN, RELIEF ACCENTUATES

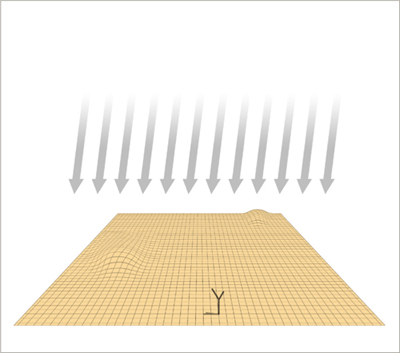

Shown with directionless light at the top for comparison, this is what happens as the sun sets in clear light. Prominent things sticking up, like trees, already cast a distinct shadow, but this lengthens spectacularly, while less obvious features like hills eventually cast shadows that darken the entire landscape, spreading east rapidly toward the end.

TROPICAL HARSH Midday on Lake Inle

Key Points

Vertical Light

Hard Edges

Solid Clouds

Low latitudes, around the equator and into the tropics, take the sun even higher in the middle of the day, which means that if you insist on going for traditionally “pretty” each time you shoot, your working hours are going to be quite limited. It’s best to find ways of accommodating this high and harsh light into the photography.

Monk & lake monastery, Ywama, Lake Inle, Myanmar, 1982

And one more thing: Lighting can contribute to giving the experience of being somewhere, and especially somewhere different. This idea is historically quite recent, at least since large numbers of people began traveling sufficiently to actually care what the places felt like. In the 19th and 20th centuries, there was a near-universal interest in what foreign places looked like; hence early photographers such as John Thomson, Carleton Watkins, and Edward S. Curtis traveling with plate cameras through Asia and the West of America, and the later success of magazines like Life, Picture Post and National Geographic. This is not to say that photographers were any less concerned about light, but using it for sensation was lower on the agenda than it has become recently. The tropics became a recognized destination for travel around the 1970s, when long-haul travel started to become affordable and made tropical beaches a possibility for a week’s holiday. And there’s no doubt that the tropics deliver a different experience to most people, quite apart from their cultures and landscapes. So, far from avoiding the tropical midday, with its top light and often stunning heat, there’s every reason to explore the lighting effects. This is Lake Inle in Myanmar, with intense and high sunlight, bouncing off the water to be almost blinding and giving those solid-looking cumulus clouds that have been building over the hot landscape for the last couple of hours their characteristically tropical look.

Tropical Harsh Light

Tropical light comes into its own in the middle of the day, when by the mid-latitude standards of Europe and North America, the sun is unusually high and the shadow footprint tiny, but intense.

Everything here on this shallow body of water is built on stilts, including the Buddhist monastery at right and the walkway. The monk was approaching, and I followed him. Daily life goes on regardless of whether the light looks pretty or whatever, and this was not a case of waiting for another monk to come by later in the day, even if I wanted that. In any case, the traditional lacquered paper parasol makes the shot, and here it was very much a midday accessory. ![]()

Mirrored reflections emphasize clouds & deep shadows

The clouds, top-lit and very white, have a typically tropical solidity, in this case worth making something of by repeating them with their reflection in the still lake.

One of the qualities that a high tropical sun has going for it is that it casts shadows almost vertically, and this is something unfamiliar to anyone from the other latitudes. In particular, it means that underneath trees there will be dappled light, and this is guaranteed all the more because the tropics have more broad-spreading trees than elsewhere. In fact, such broad-spreading trees were deliberately planted in tropical towns for the very purpose of shielding parks and pavements from the sun, and are usually called “shade trees.” This is what is happening here in this Caribbean island village of Baru, where the time I visited was not exactly what I would have chosen. A feature of the village is its inhabitants’ clear love of color—pinks, yellows, greens, reds, and here, blue.

Blue house, Baru, Bolívar, Colombia, 2011

My first thought was that I should return when the sun was lower, because the old blue house was definitely worth shooting; so like most of us my reaction tends toward the guaranteed light that I know well, with the sun lower. But while I was here there was no point wasting the opportunity, so I scouted around for a way to handle this. It was not an architectural shot, so I was looking for some combination, which meant people, though there were few about at this time of day. Then it dawned on me, as you can see from the sequence, that the distinct pattern of dappled light and shade could become part of the composition. Rather than angle the camera upward to avoid bright ground, and then have to deal with converging verticals, I could use the pattern to counterbalance the house. I also included in the middle-distance the blue house’s companion yellow-and-red building, to add to the sense of colorfulness. I found a stone to stand on so that I could keep the camera level and the verticals more natural, and waited. Anyone passing by would also be in this dappled zone, and so mainly dark themselves, and the ideal place to have them in the frame was where the girl is—between the two colored houses, virtually in silhouette. This kind of dappling is technically chiaroscuro, which I go into in more detail on pages 132–135. ![]()

Tropical shade

Overhead branches and an overhead sun create a complex and high-contrast chiaroscuro pattern.

Working toward the shot

The sequence from finding the building, wondering whether the shot could work in this harsh light, and moving to make the dappled shadows an integral part of the image.

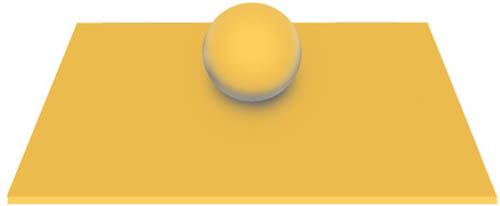

SNOW LIGHT The Ultimate Reflector

The tropical light we just saw is a kind of environmental light, depending very much on place. Another is what I call “snow light,” which is when snow covers the ground and as a result has a major effect on the light overall. Snow completely changes the normal relationship between ground and sky, which tends to be dark below and bright above. In a cloudless sky, the snow-carpeted land will be much brighter than the sky, and even when cloudy, there’s more of a match. This means that not only is there much less of a sense of light coming down onto a scene from above, but that objects in the landscape receive a lot of bounced reflection from below.

Japanese crane, Hokkaido, 1997

Fallen snow is, in fact, unique in landscape lighting, and its nearest competitors, beaches and water, don’t really come close (with the single exception I know of being White Sands in New Mexico). There are a number of things you can do with it, and one of my favorites is to use it as a kind of white canvas background for things happening in the snow. The Japanese crane standing in the shallows of a snowbound stream may not be typical of snow photography, but it gives a hint of the range of effects. This occasion happened to include some freezing fog, which only added to the ethereal bluish white light.

Japanese crane, Hokkaido, 1997

And when the sky is clear, one short-lived effect happens at the ends of the day, easily missed if you don’t know what to look for and aren’t in the right position for the several minutes that it happens. As we will see on pages 60–61 with the waterline shot of Lake Dal, the sharper the angle, the more perfect the reflection, and the same thing happens with snow—even more so if it turns to ice. In the late afternoon shot of a crane on the left, taken with a 600mm lens, the gentle rise of the slope meant that we’re almost at the level of the snow, which catches the delicate pink of a weakly setting sun over Hokkaido. ![]()

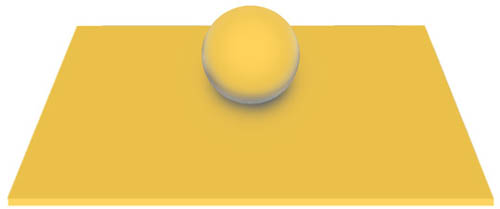

The sun’s reflection in snow

Ordinarily, a covering of snow acts as a broad reflector, uplighting objects (below left). But near sunrise and sunset, from a low angle it picks up the pinkish glow, adding a special subtlety.

INTO THE LIGHT Reflections & Refractions

It’s one of the simplest lighting actions to take, yet with the biggest effect. Turning around from the default position, in which light shines on the subject from somewhere more or less behind you, so that you now face directly into the light, changes everything. Suddenly, from the technically efficient and simple, you’re dealing with many of the things that make camerawork complicated and unpredictable: flare, high contrast, silhouettes, and uncertain exposure. But what you can get from shooting into the light is mood, atmosphere, and creative choice. There’s more room for individuality in this kind of situation, and there is certainly a choice of treatment. At one end of the treatment scale is the dense, rich silhouette. At the other is the flared, well-exposed style which opens up the foreground shadows but lets the bright detail behind go off the register to pure white.

Cienaga de Cholon, Caribbean coast, Colombia, 1979

The conditions need to be bright and sunny, and the sun, or its reflections, needs to be low enough to be in-frame. This happens in several other lighting situations in the book, including golden hour, reflection light, edge light, and sunstars, but even so, this is so distinctive a kind of lighting that it merits its own entry. For the next several pages I want to look at the variations of into-the-light, and there are many. Here, to introduce the theme, are two of the classic evocative effects of shooting toward the sun: reflections off of surfaces and refractions through something. The reason why they are an important part of this kind of shooting is that they bring the sun actually into the scene, rather than having it just sitting above and behind.

Shooting toward the sun

Compare this illustration with the alternatives at the same time of day on pages 94–95.

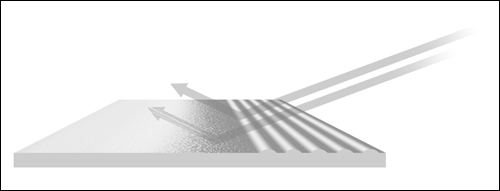

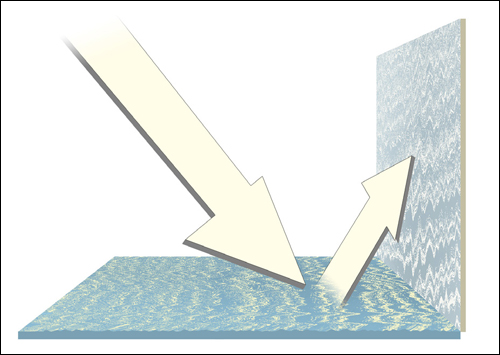

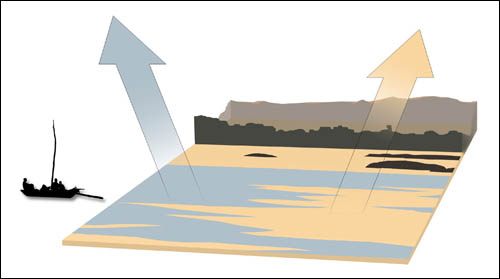

Reflections are about angle: your angle to the surface you’re shooting, and the sun’s angle to the landscape. It would be a little tedious to start talking physics at this point, but with a flat surface, like water, the lower the sun, the lower the camera position needs to be in order to catch the brightest reflection. Basically, the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection. Under Reflection Light—Concentrated Bands on pages 64–65, there’s a side-on illustration that shows this. The angle at which the sun strikes the surface is the same as what you could call the viewing and shooting angle. In the picture here of a canoe being slowly paddled across a lake, the sun has only just risen, which you can tell because I was shooting from another such boat, close to the surface. The ripples, however, which help make the shot, are reflecting different things, and the dark bands are from the trees out of frame behind.

Refractions are another way in which the sun interacts with the scene. To have refraction, the thing that the light shines through has to be transparent or translucent, and the many effects are because of the change of angle of the light. On the left is an obvious one, bottles (of oil) for sale in Omdurman market, Sudan. But clouds also refract light, which is why the sun behind clouds that are not too thick can make such a variety of effect. ![]()

Oil bottles, Suq Libya, Omdurman, Sudan, 2004

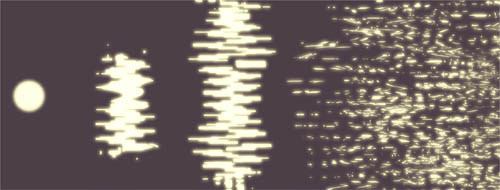

Shooting directly into the sun carries its share of technical problems, simply because of the huge range between the sun’s disc and foreground shadows. The term for this is dynamic range (what photographers pre-digitally used mainly to call the contrast range), which technically speaking is the ratio between the maximum and minimum light intensity in a scene. There is also the dynamic range that the camera is capable of, and the dynamic range of how you show the final image, whether on a screen or as a print, but for the time being let’s discuss the scene dynamic range.

Cow Close, Wharfedale, Yorkshire, 1980

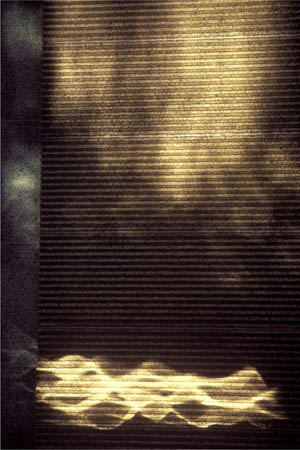

Shooting straight into the sun gives about the highest dynamic range that you can face in photography, and in fact, truly high dynamic range (HDR) means any view in which the light source itself is visible. For more on HDR see Archive Light—What HDR Really Means on pages 242–243. Oddly enough, dynamic range was less of a problem with film than with digital, according to my point of view (not everyone’s). This might sound strange, given that digital images have such amazing potential for being processed any way you like, but one of the differences between film and a sensor is clipping. The way film responds to having the sun in-frame is to grade smoothly from highlights to the out-of-range white of the sun. A sensor just loses it sharply, because once each photosite on the sensor is full of photons, it delivers pure white to the processor. This is known as clipping, because there is a sharp cut-off in what the sensor can record of highlights. It also varies by channel between red, blue and green. One effect of this, when the colors go beyond the gamut of the color profile, is banding, which, as you can see from the image on the right, looks terrible. It takes some careful processing to avoid having these odd-looking bands encircling the sun. The glass-like river scene in Golden Hour—Facing into Soft Golden Light on pages 98–99 needed just this careful processing for the sky around the sun to look smooth.

A detail of an into-the-sun shot processed normally (below left) with evident banding, and with processing attention (below right) to smooth out the gradation.

None of this is any reason to avoid shooting into the sun, but be aware that the processing will take longer. This banding reduces if you reduce the exposure with the Raw converter’s slider; also, the Raw converter’s highlight-recovery slider will help. It may even be necessary to make two versions from the Raw converter and blend them later. Finally, using Replace Color in Photoshop after Raw conversion allows you to target “bands” and change their hue (yellow tending to green is common), saturation and lightness. An alternative if you have the camera locked down is to shoot a range of exposures and make an HDR image file. See pages 242–247 for more on this. ![]()

Irula rat-catchers, Tamil Nadu, India, 1992

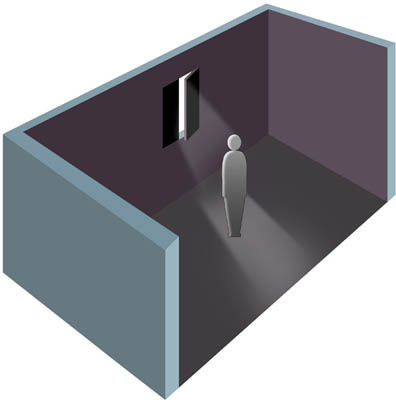

INTO THE LIGHT Blocking the Sun

You can shoot into the sun without having to see its disc, and avoid the dynamic range problems that we learned about in the previous pages. One useful way around the dynamic range problem is to position yourself so that something blocks the sun’s image. The dynamic range is still high, but more manageable. Depending on what is doing the blocking, and on whether there is space beneath it, there are two possible side effects, and they can be turned to advantage in making the shot more interesting. One is a cast shadow, the other a reflection of the sun on the ground or whatever other flat surface you see.

Oak Alley Plantation, Louisiana, 1978

For a cast shadow, much depends on the shape of the object, and also on the texture of the ground. The example I’ve chosen here is a well-known antebellum mansion on a plantation in Louisiana, on the banks of the Mississippi. Called Oak Alley Plantation, it has a long alley of 300-year old live oaks, broad-spreading and with heavy branches. Blocking the sun with one of these made it possible to use its powerful shape a second time in the image, by bringing its shadow on the light-green grass into the frame. There’s a strong link to silhouettes with this way of positioning yourself, and there’s more about that under Backlight—The Silhouette on pages 70–71. The difference is intention, because silhouette is about shape and outline and a deliberately two-dimensional cutout effect, while here the idea is more to do with light management. Nevertheless, in this image, the combination of silhouette and shadow, twisting and enclosing, has become as important to the composition as showing the mansion in the background.

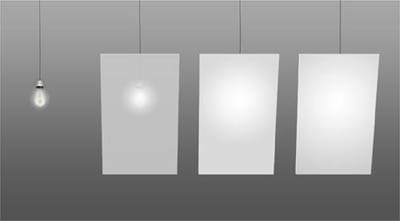

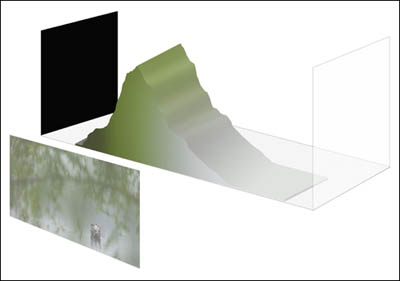

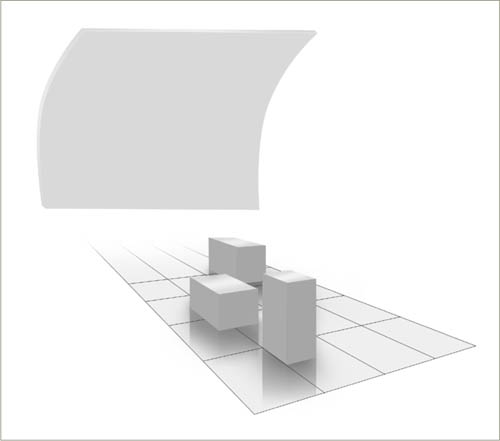

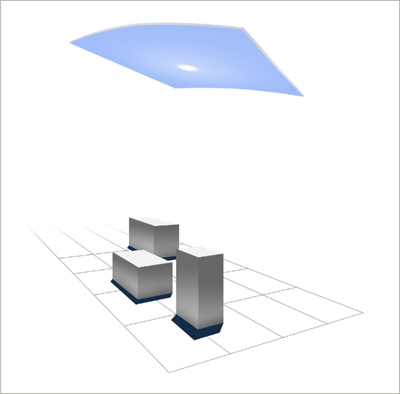

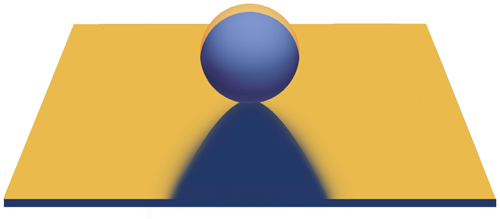

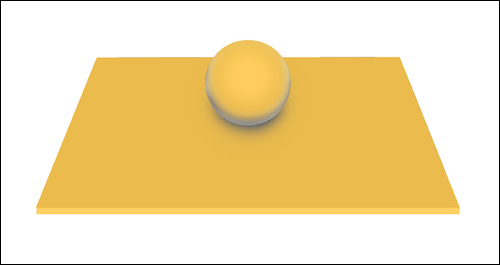

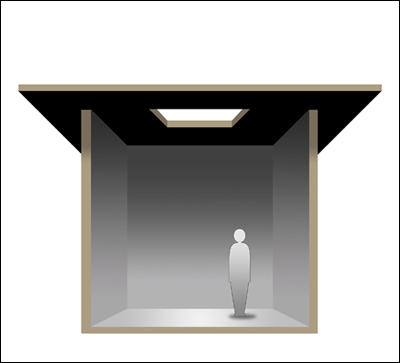

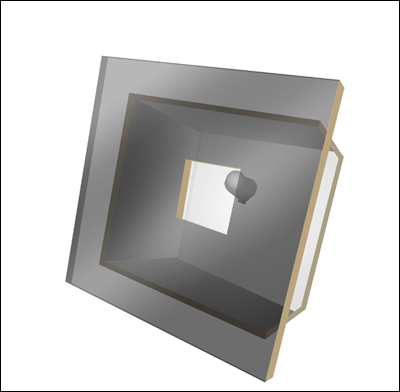

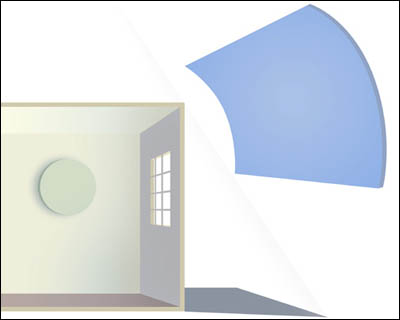

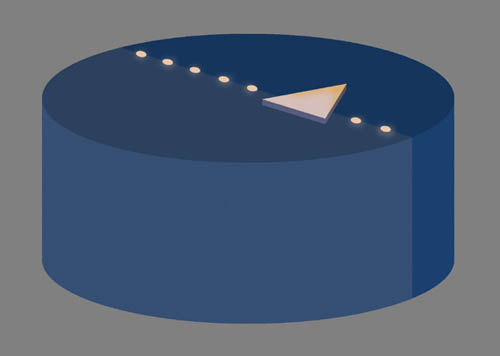

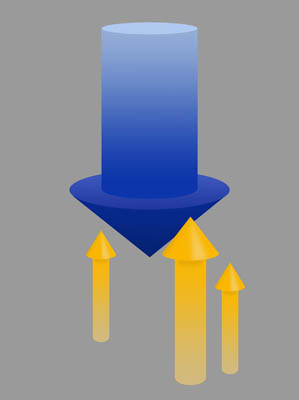

Two lighting effects from blocking

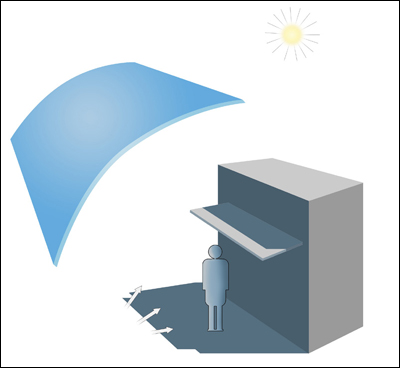

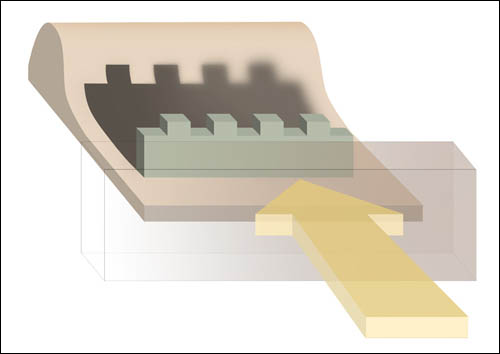

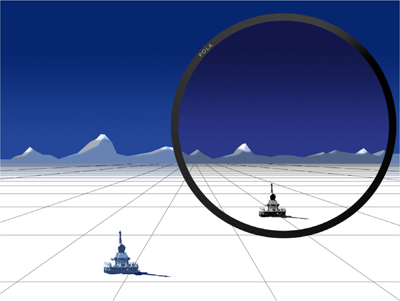

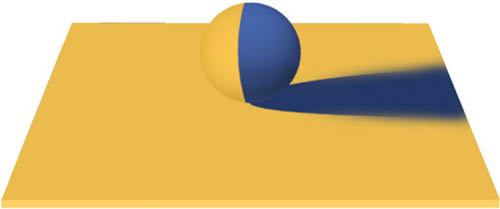

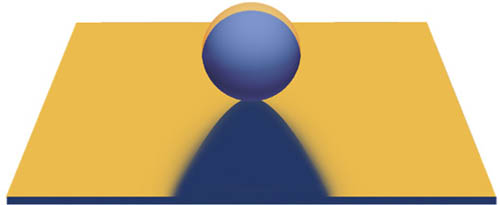

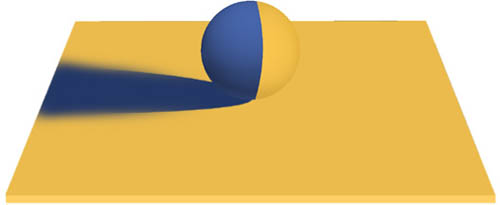

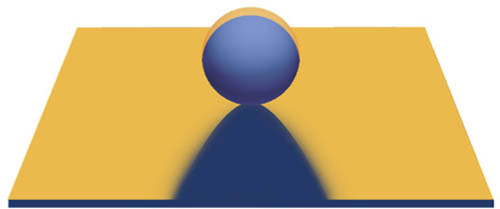

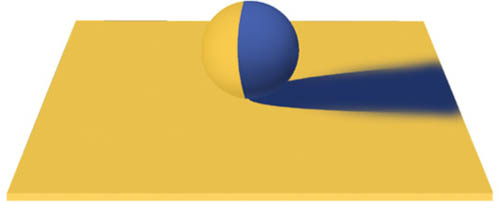

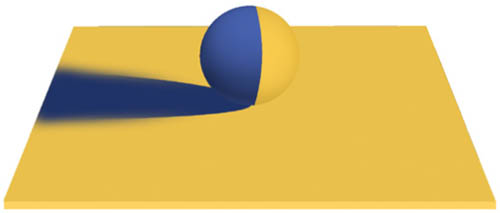

The floating cube stands in for any number of objects that you could put between you and the sun (this view is slightly above camera level). It both casts a shadow on the ground and, if there is any shininess to the surface, reveals the sun’s colored reflection.

The second image, of what was at the time the principal spy aircraft for the U.S., uses the reflection effect that the illustration here shows. I had spent the afternoon having the Blackbird towed around the airfield at Beale AFB, and this was to be the last shot before sunset. Of course, gauging the exact point of sunset and having the aircraft positioned exactly on the axis between sun and camera meant a lot of messing around, but it was worth it. I did not want a silhouette in this case. Instead, I needed to show detail, hence blocking the sun to pull down the dynamic range, and with the camera low on the runway pick up the red glow of the sun’s reflection. If the sun had been in shot, incidentally, it would have overwhelmed this kind of reflection. ![]()

SR-71 Blackbird, Beale AFB, California, 1986

SHADE TO LIGHT Looking Out & Beyond

Key Points

A Stage Set

Natural Progression

Leading the Eye

Standing back from the sunlight, either inside or in the shade, and looking out is also a classic way of framing a shot. More even than the examples we just saw, it makes use of the natural, almost unavoidable tendency of the eye to move toward the light. Added to this is some psychology, because in an image like this one, not only is the viewer firmly placed within the scene, looking out, but there is a sense of the outside sunlit scene being somehow positive and attractive. That, at any rate, was the idea behind this view of Canterbury Shaker village in New Hampshire on a bright fall day, seen from a Shaker-built rocking chair. Exposure is key to this kind of shot. If set so that there is more detail in the shadows and the outside is washed out, the eye is not invited quite so strongly to move outward. Here, the exposure was for the exterior—but then a touch lighter—so that there is everything to look at. The sun streaming in through the doorway keeps the chair and door alive, too.

Rocking chair, Canterbury Shaker village, New Hampshire, 1985

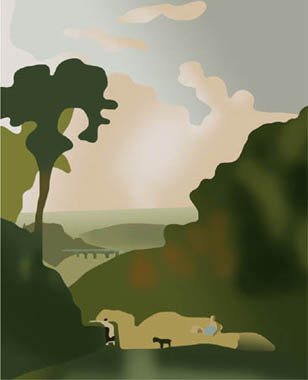

This effect of pulling the eye out toward the distance, almost despite itself and working both visually and psychologically, was used in painting well before photography hit upon it. I’ve mentioned this before, in The Photographer’s Mind, but it’s worth re-visiting. The hugely influential Claude Lorrain, the great seventeenth-century landscape painter who first began treating landscapes as subjects in their own right, devised a way of constructing a composition that led the eye very precisely. It was one of his most distinctive treatments, and goes as follows. A dark, shadowed foreground, weighted and partly framed to one side with trees, like the wings of a theatre. On the other side, and a little beyond, another framing mass, not quite as dark, but still like a theatre wing, so that the scene becomes a kind of stage set. Beyond, the landscape receding to the horizon becomes lighter and lighter, and the sky lighter still, because the view is into the sun. This structure and lighting takes the eye from the foreground on one side across and beyond to the middle ground, and then toward the luminous distance and sky in the center and slightly above. The image has structure, and leads the eye.

Later painters copied these ideas, not least another great landscape painter, J.M.W. Turner, as the illustrations show. A key addition to moving the eye from shade to light was that classical landscape paintings also needed human figures, and both Lorrain and Turner used another special technique to coax the viewer’s attention. They created a pool of light within the foreground-to-middle ground. Two great examples are Lorrain’s “Rest on the Flight into Egypt,” painted in 1644 (his “Moses Saved from the Waters,” 1639 is startlingly similar) and Turner’s “Crossing the Brook” from 1815. The human eye is naturally drawn to figures and faces, so this mini-scene draws the attention before it goes off into the distance. ![]()

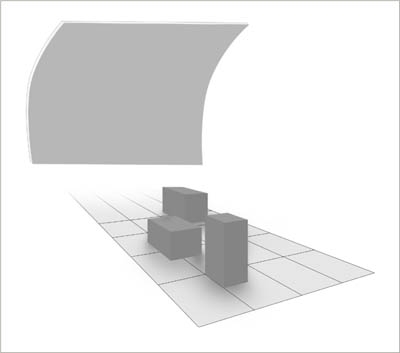

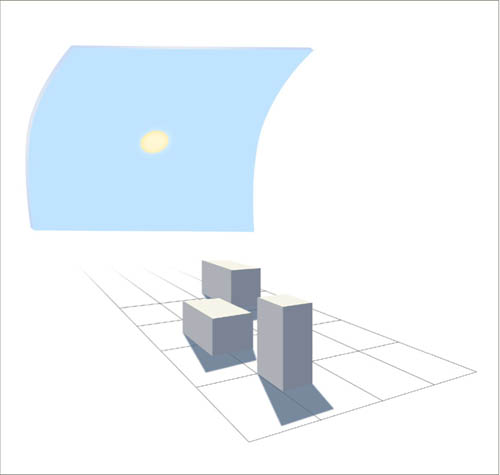

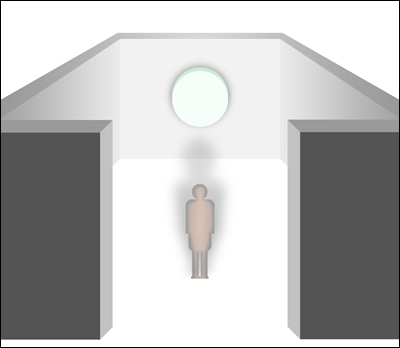

Shade to Light

Looking out from a shaded area into the light reinforces our natural attraction to brightness, and so leads the eye very strongly toward the distance.

Claude Lorrain’s “Rest on the Flight into Egypt,” 1644

This highly influential landscape painter developed a much-copied method of leading the viewer’s eye out toward the distance through a series of darker foregrounds and middle grounds.

J.M.W. Turner’s “Crossing the Brook,” 1815

The British painter Turner made great use of this method from Claude Lorrain, as here. The pool of light with people in the near-middle ground is typical.

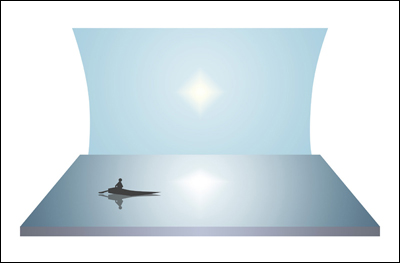

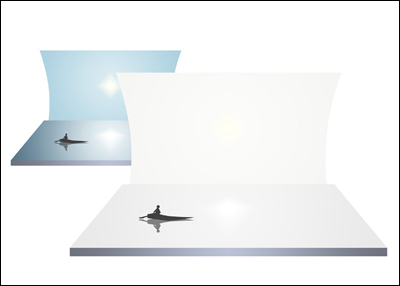

REFLECTION LIGHT Mirror Smooth

To avoid any confusion, here I’m talking about shooting into the reflections of light, rather than using reflected light to bounce up onto a subject—that’s dealt with later, in Reflected Light from pages 188–197. The reflections here are of the sun and the sky around it, usually in water and bright and sparkling. Being reflected, it’s a touch less bright than the sun itself, possibly around one ƒ-stop, but much depends on what happens to the water, as we’ll see on the following pages. Here to start with is the setting when the water is mirror calm, and the reflections are close to perfect. This is a lot more common when the water body is small and shallow, naturally, so that when there is the same effect on a lake, for example, we immediately see it as being slightly special, an unusually still day, probably an early morning before the day has really got moving. The angle to the surface is important, because the lower the camera—the sharper the angle, in other words—the stronger and brighter the reflection.

Shikara on Lake Dal, Kashmir, 1984

Rice paddy below Tirtagangga, with Gunung Agung, Bali, 1996

Mirrored reflections of sun & silhouette

Approximately a stop darker than the scene above water, near-perfect reflections like this catch a mirror image of the sun at the high end of the brightness scale, and the silhouette of anything floating at the dark end.