5

Of all the jobs within the game industry, that of the writer is probably the least defined and most misunderstood. Sometimes an actual writer is hired to script the game, but more often than not the script is formulated by the creative director or the producers involved with the game. This runaround becomes evident in some titles through the sheer lack of good story and an overabundance of paper-thin characters contained within the game. In the past, I’ve dealt with producers who regard the role of the writer as writing the dialogue spoken by the characters in-game. This approach is indicative of the ignorance concerning what a writer actually does and the lack of concern the game industry has for story.

While writing this book, the Writer’s Guild of America was involved in a strike and petitioning for better compensation. Believe me, the effects of this are being felt in Hollywood and throughout the television and film industries! This is mostly because these industries are clearly aware of the importance regarding good writing. Nothing is as important to the success of a film as the script. This approach needs to be used more often in game development. Imagine the impact that a great story will have on a gamer when coupled with the interactivity of awesome game play.

Clearly, some titles have made more of an effort than others to set a higher bar regarding story and characters—games like the popular Halo series, the Tom Clancy branded titles and even horror-based games (like Silent Hill and Resident Evil) have decidedly better production value in this regard. Coincidentally, Silent Hill and Resident Evil have both already been produced as movies, while Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell and Halo are currently being developed for the big screen as well.

Another bad practice in the game industry regarding writing is not starting to write a script until well into the production cycle. This error is completely unacceptable if you want an immersive, cinematic game. The script should most definitely be honed in preproduction or during the concept phase and turned in as soon as possible to allow the game designers and all concerned to have some sort of map regarding the story before production begins. It’s true that some game studios have been burned in the past by writers (usually because the writer placed the need for a great story above the costs of changing the game’s design), but it is still a good idea to have the writer in place during preproduction, if for no other reason than to help create a sort of flowchart or formal outline for the story.

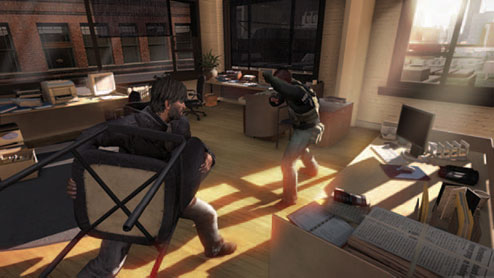

The Writing in Capcom’s Resident Evil Series Contributes to the Overall Atmosphere and Horror of the Game. Reproduced by Permission of Capcom U.S.A., Inc. All Rights Reserved.

The first step in recognizing and fostering good writing in the game community is to standardize some of the writing processes involved with game development. There are several cinematic cues that can be taken from the film community concerning this.

5.1 Format and Script Development

Unlike the game industry, the film industry has had a standard script format for quite some time. The benefit of this is obvious: writers know exactly how to write for a project and what is expected from them when turning a script in. Even the processes for developing a great script have been honed to empower the screen writer with the tools necessary for completion. Though many writers may disagree on what exactly constitutes good content for a script and what different literary tools and images should be used within the pages, all screen writers can agree on what the final script should look and read like.

As mentioned earlier, the game industry has many different ways for writing game scripts. Most of the problems involved with writing has centered around the difficulty of dealing with all the possibilities of interactivity. A screenplay may have only one path concerning what will happen in a movie or television program, but a game may have multiple paths. For a game to be as enjoyable as possible there should be many paths that a gamer can choose to take. Each of these paths must be scripted and accounted for. How does a writer do this?

The Lord of the Rings Online Series of Games from Turbine Features many Paths that a Gamer can take. The Artwork Appearing to the Left is Copyright Protected and Reproduced with Permission. © 2008 Turbine, Inc. All Rights Reserved. This Publication is in No way Endorsed or Sponsored by Turbine, Inc. Or its Licensors.

There are several popular methodologies regarding multiple-path writing, but the two most popular seem to be the “multiple columns” approach and the “choose your path” book approach. Either way, for complete coverage of the game, game writing should center around the use of events, decisions, or locales—and should contain some methodology for tagging dialogue to these.

The use of multiple columns is already prevalent in screenplays; in fact, most screenplay programs that are in use have this function already included (sometimes this is referred to as a “dual dialogue” function). In this game writing methodology, you write the action, present a choice, and then approach the different choices available to the gamer in a separate column beneath the action. If, after the decisions of the gamer have been made, the end result is singular and the next scene or piece of action will be the same regardless of choice, this is probably the best method for writing the script. However, if there are truly many different ways to play and finish the game (meaning some paths are never explored during game play), consider the technique of using a “choose your path” book style of writing.

“Choose your own path” books have been around forever; essentially, you read a portion of the book, a choice is given, you make a decision regarding what you want to do, and then you turn to the appropriate page to pick up the action based upon your decision. When employing this method for writing your game script, the various pieces of action are written, then connected using hyperlinks and bookmarks. Though this type of writing does not resemble a screenplay, in some circumstances, it can better serve a project. Because most games do have a definite ending and game levels are limited, it is usually the intent of most developers to make the entire game playable in every session. That said, there’s no reason why most games cannot be made using a standard screenplay format. But don’t let the format for the script hang you up!

Having read for several major screen writing competitions (the Austin Film Festival’s, for one), I have seen many great stories passed over due to poor formatting and style. As a gaming writer, you will not have to face such harsh scrutiny! Instead, you can use the best practices of script development to help write a great story for your game using the best format possible.

Development Tip

![]() Download a copy of the free software Celtx today (http://www.celtx.com). It’s a script formatting program that also has features that help develop your story and characters, as well as track changes made to the script.

Download a copy of the free software Celtx today (http://www.celtx.com). It’s a script formatting program that also has features that help develop your story and characters, as well as track changes made to the script.

Though it may be difficult to actually sum up what makes a story great, there are several main components of a great story that can identified. The first is the use of well-developed characters. The creation of a memorable protagonist and antagonist is the first step towards writing an epic story.

The protagonist, to put it simply, is the hero of the story—and within a game, is also the gamer! Creating a great main character is the cornerstone of the script. Great examples of this already exist in the game world—who doesn’t know Master Chief of Halo fame, or Sam Fisher, the undercover agent in Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell? Not only will your protagonist fulfill a great need of the gamer, but he/she can supply your game with a calling-card franchise character. There are several characteristics that mark a great protagonist.

Ubisoft’s Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell Series is Anchored by the Great Character Sam Fisher. Reproduced by Permission of Ubisoft. All Rights Reserved.

Film guru Robert McKee states, “A protagonist is a willful character,” in his seminal book Story. It is in the examination of the character’s “willfulness” that will create the motivation for your main character, as well as define a past that is relevant to the present within the game. Sometimes this is called a “back story”. Although a back story can be extremely useful for answering some of the why’s involved with the game, it should be used only in a way that provides motivation for the character in the story. Writing a lengthy back story only bogs down the game and story and detracts from the game play.

In addition to brainstorming the particulars of your characters (background, ethnicity, profession, and so on), the main goal of the protagonist should also be defined. It is the goal of the protagonist that forms the plot of the game. Though there are many different ways to approach creating just such a character, perhaps one of the best ways of defining your protagonist is to create a pertinent antagonist.

The antagonist is usually the “bad guy” in the game. When created correctly, the antagonist actually complements the protagonist. Maybe they are rivals with much in common. Maybe they completely contrast against each other in both personality and substance. A great way to craft a memorable antagonist is to give him or her an opposing goal; this can be as simple as the antagonist’s goal being to stop the protagonist’s goal (or vice versa) or it can be the same goal, putting the two characters in direct competition. Either way, having a great villain is another useful way to add production value to your script. Games that have a memorable antagonist go a long way towards being cinematic.

Once you have created the main characters, it’s time to move on to the major supporting characters. It’s a good idea when creating the sidebar characters to include various demographics not covered by the two main characters. Want female gamers to buy your game? Have a great female character. Not only does this help with broadening your audience, but it adds variation and diversity to your story. Use character breakdown sheets when developing the various details involved with creating the characters (see the sample character breakdown sheet in Appendix A: Extras).

When you are developing characters, keep in mind that the interactive aspects of gaming should be coming into play! One of the more fun ways to develop an interactive story is to allow for changes in a character’s personality versus changes in the environment. In other words, instead of having a player choose between taking the rickety bridge across the river or swimming for it, have the player choose between killing innocent soldiers on the bridge to get across or risking his or her own life swimming across dangerous waters. As a game progresses, a character can become more “evil” or “good” based upon decisions the gamer has made and this can change the options made available to the gamer.

When all the major characters have been defined and created, you can now move on to identifying the major theme(s) contained within the game.

Think of the theme as the lesson to be learned from the story. It doesn’t have to be preachy. It can be as simple as “crime doesn’t pay” or “you can’t escape fate”. Whatever the theme is, it can usually be summed up by the original intent of the game creator. What was the original message you wanted to project to the world when you formed the original concept of the game? Perhaps the game was conceived to fulfill a particular vacuum in the gaming industry. What was this? This overall idea should be considered as an outline before the script is developed and the particulars of the story are discussed. It is an important task for the writer to keep the script within the theme of the story.

Some argue that a theme is unnecessary in a game and that a game should be squarely created around fun and features. This is fine. Even if there is no grand underlying idea in the game, working with basic emotions, motivations, and desires of the characters strengthens the story contained within the game.

The Game Assassin’s Creed from Ubisoft is Full of Topical Themes Regarding the Middle East, Religion, and Cultural Differences. Reproduced by Permission of Ubisoft. All Rights Reserved.

One of the tools that the writer often uses to keep the story within the original theme is the use of cleverly placed symbols. This is called “symbolism”. Symbolism can be an extremely complicated affair or as simple as the use of a prop. An example of prop symbolism could be a wedding ring that represents the love of the protagonist for his wife and family or a lucky keepsake that goes missing (and when it’s found, the luck of the character returns with it).

Symbolism can also be a very complicated thing such as placing enough references to an evil organization or corporation to make the gamer think of a particular religion or government. Either way, the use of strategic symbols and symbolic props is another method for getting production value into the script and game. When coupled with the best practices involved with constructing a solid script, a great story is created. The use of symbolism, though, should be supported by the theme of the story and not just placed within the game in an attempt to make the game “deep”.

The use of the many best practices of screenwriters will help you develop your script. These best practices can be summed up with three major elements: story, plot, and scenes. When used together, these three elements add up to give your script a well-defined structure.

A great structure means getting your protagonist from Point A (the beginning of the game) to Point B (the end) in the most entertaining way possible. Although this is determined to a great extent by the goal of the main character, actions are also influenced by the various outside elements involved within the story. To begin the process of creating good structure, the story must first be broken down into a basic group of manageable chunks (scenes) that move the story forward in the desired direction.

The script should be able to be broken down into scenes relatively easily. In the film industry, this is called “breaking down” a script. When you have broken down the script, you should be able to easily identify the individual levels and areas of play within the game. Sometimes, it will also identify key sections in the script that will not be able to be included in the game play. In a game, this usually means that a connecting cut-scene will have to be created.

Scenes are the smallest unit of measurement in a script—usually just a few minutes—and have a beginning, middle, and end. In a game, this can be introducing a new level, a new location, or sudden shift in action. A new scene can also be created when a new character is introduced. Once you have mapped all the scenes/ levels out, place each of the scenes under a magnifying glass. Ask these questions: Is the scene important? What are the goals that are trying to be accomplished? Would this scene stand up on its own? Every scene needs to be exciting and fresh to the gamer. If a scene does not have what it takes, take a look at the elements involved and decide what needs to be changed.

Perhaps changing the location (keeping in mind that this could be creating another level that will need to be created within the game) or a twist in the story that’s unexpected (one of your squad members turns on you!) would make the scene better. Whichever method you use, make sure that it is consistent with the overall feel and style of the game and within the original concept! There can be multiple writers involved with a game, so it will become a huge task to ensure that they all adhere to this. Once the scenes have all been honed and are the best they can each be individually, you should be able to see a coherent story contained within the script. If the story is not coherent, it will become evident fast when the quality assurance team starts to dissect the game during production.

The final element involved with defining good structure is that of plot. If you’re thinking of what constitutes the story as “this is what happens”. you can think of the plot as “this is why it happens”. Basically, it’s cause and effect—motivation and reasons on the part of the characters. Setting up a good reason for the protagonist to take on the mob makes the game more believable. Is it revenge? Is it the desire to rule the underworld? Both are great plots and both contribute to creating completely different scripts. Once the story, plot, and individual scenes have been articulated, you can approach writing the actual first draft of the script.

Development Tip

![]() Robert McKee describes an “event” in his book Story as something that creates change. This is a good rule of thumb. When events happen in the game, they should have meaning. The more meaningful each event is that occurs, the deeper the immersion the gamer will experience, and the more cinematic the production.

Robert McKee describes an “event” in his book Story as something that creates change. This is a good rule of thumb. When events happen in the game, they should have meaning. The more meaningful each event is that occurs, the deeper the immersion the gamer will experience, and the more cinematic the production.

Most Hollywood movies are actually written in what is called a “three-act structure”. The famous screenwriter Syd Field first wrote about this method of writing a script many years ago in his book Screenplay. Basically, the three act approach consists of dividing a script into three major sections: the setup, the confrontation, and the resolution.

Many screen writers today do their best to avoid using the typical three-act structure (many feel the approach is clichéd), but almost all finished scripts end up presenting a story in this fashion. Though it is sometimes considred to be predictable, the truth of the matter is that there is nothing more basic to a story than having a beginning, middle, and end. Avoiding an ending doesn’t just “buck the system”. It creates an undesirable aftermath when the game is over and leaves behind an unsatisfied gamer. You don’t want to leave your audience hanging…unless of course, you are planning a sequel that will be picking the story up again!

The first act of the screenplay, also known as the setup, is about getting the protagonist in motion. This means creating an “inciting incident”. The inciting incident is the event that occurs that gets the protagonist on the path to resolution. Examples of a setup include the moment in Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, when the king is killed and the gamer is set on the quest to restore the throne and the opening level in Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, where an assassination prompts the United States and the United Kingdom to scramble special operations troops to prevent a world incident. Whatever your inciting incident is, it must be compelling and warrant the gamer investing time in playing the game.

The beginning of the script should also focus on setting up the situation that your protagonist is getting into and the basic locations that will be visited. This focus lays down the foundation for the tone of the game; is this about adventure and exotic locations, or is the tone more subdued and familiar? Once the foundations of the story have been laid in the first act, you can then move on to the second act.

Activision’s Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare Uses a Strong Story Structure to Carry the Game’s Narrative. Reproduced by Permission of Activision. All Rights Reserved.

Act II of a three-act script is also called the confrontation. Another way of looking at the second act is to think of it as creating conflict. It’s an old Hollywood axiom that most scripts fall apart in the second act. The writer created a great character, set up a great opening scene and inciting incident, then failed to move the story forward in any way. The second act of your script should be about conflict. What is standing in the protagonist’s way? This can be handled by focusing on the antagonist or by creating obstacles that now stand in the way of the protagonist. The best screenplays exploit both paths. In the gaming world, though, it is best to concentrate on creating obstacles. By doing so, the gamer is presented with a series of challenges that must be overcome within levels. This presents many opportunities for awarding the gamer with achievements and increasing the level of immersion in the game.

Once the meat of your script has been created in the second act, you can then move on to the third and final act. The final section of the script should be centered around the concept of resolution. The final levels of the game should test the player’s resolve to finish the game, as well as create moments that resolve the various elements of the story. A great story provides the gamer with some level of resolution. Once again, think of the central theme of the story. A great resolution not only brings the game to a satisfactory ending (usually by allowing the protagonist to “win”), but also supports the central theme of the story: good conquers evil, or there is no fate, or even order suppresses individuality.

Development Tip

![]() If you are having difficulty getting a specific level honed to perfection. Think of the scene as a series of beats. A “beat” is a specific action that moves the plot forward within the scene. By breaking down a level by each action, you can create an accurate minimap of what happens in a specific level.

If you are having difficulty getting a specific level honed to perfection. Think of the scene as a series of beats. A “beat” is a specific action that moves the plot forward within the scene. By breaking down a level by each action, you can create an accurate minimap of what happens in a specific level.

That said, once you have broken down the basic three acts of your script, you can now divide each act into a group of smaller, individual scenes or levels that you have crafted. Each of these scenes move each act towards the inevitable ending of the game. At this point, the major conflicts involved with the story, and the resolution, should be blatantly obvious. Make sure you include the necessary scenes that will bring your story to completion; necessary scenes (also called master scenes) are those that directly support the resolution of the story. You will also want to have scenes that concentrate on the game’s subplots (especially if there is a love story or back story that can be visited through the use of flashbacks). The three-act structure can assist you in completing the first draft (and subsequent drafts) of the game script.

Check out Far Cry Instincts: Predator by Ubisoft to see a Game with a Great Three-Act Story. Reproduced by Permission of Ubisoft. All Rights Reserved.

Again, as there are no standards in formatting, it is perfectly acceptable to approach writing your game script like writing a movie script—it can even help you later on (if the game garners attention for possible optioning, you will already have a recognizable script that can be circulated as part of a movie pitch). As the drafts of the script get closer and closer to where you want it, you will begin to see a certain style emerge that is reflective of the script writer(s). Pay attention to this style. When rewrites occur later on in production because a level was suddenly cut, you will want to have the writer available who contributed to this in the biggest way.

Creating a great script, even in the best of circumstances, is usually a collaborative effort. Though one person may be credited as the original writer of the script or the creator of the story, chances are good that many different people had creative input into the final version of a script. This is good—many brains are better than a single brain. When a creative director is great at communicating his or her vision, it becomes a much easier task to work in a uniform style. But at some point, you will identify a person (or persons) that will become the responsible writer for the finished product. This will probably be because of the style of that writer.

Though style is a tough thing to define, it’s best thought of as the synergy involved with creating dialogue and action that is indicative of the original vision and concept of the game—it also points to characteristics that make up an individual’s technique. Once you identify individuals who are in sync with this (and hopefully make them integral to the creative team), let them do their jobs. When given the tools necessary for them to understand the overall concept of the game, they will craft the final draft of the script you need for developing a successful title.

The collaboration involved with putting the story all together with a satisfying ending can be an awesome experience. Just remember when writing your script to keep the action moving, the dialogue fresh and memorable, and add enough twists and conflict to keep the gamer guessing; remember, the protagonist doesn’t have to win all the time!

Development Tip

![]() When creating a unique style within a script, there are several different literary devices at your disposal. These include the use of a false ending (also known as the “fakeout”), subplots that become the main plot, and the killing of main characters. All of these are referred to as the story making a “right turn”. Including right turns in your script will keep the story interesting and free of cliché.

When creating a unique style within a script, there are several different literary devices at your disposal. These include the use of a false ending (also known as the “fakeout”), subplots that become the main plot, and the killing of main characters. All of these are referred to as the story making a “right turn”. Including right turns in your script will keep the story interesting and free of cliché.

Interview: Daniel Erickson, Writer at Bioware

Daniel Erickson started his career at Imagine Media (now Future) as an intern at Next Generation magazine. From there, he helped launch DailyRadar.com and wrote for several other publications, including PC Game and Games Business. He jumped the fence into development by going to work at EA Canada, working on the first three NBA Street titles, first as a producer and eventually doing lead design work on NBA Street Vol. 2 and 3.

In 2005, Daniel chased his long-time dream and went to work for BioWare to work on Dragon Age, the RPG company’s upcoming epic fantasy game. From there, he moved down to the newly formed Austin studio and is currently Principal Lead Writer there for the studio’s first title, an as-of-yet unannounced MMO project.

Daniel Erickson

Newman: Explain briefly your background in the gaming industry.

Erickson: I started as a critic for the now-defunct Next Generation magazine and did some freelance work for several other magazines as well. I then jumped the fence to game design, cutting my teeth at EA Canada working on the EA Sports BIG franchises (NBA Street, SSX ). Once I had a couple of titles under my belt as lead designer, I made my way to BioWare, which had always been my dream, and took a job as a full-time writer.

Newman: How long have you been specifically involved with game writing?

Erickson: Three years working on just writing, but I did all of the writing on the games that I was doing design work on before as well. So seven years overall.

Newman: In your experience, do you feel that the vocation of game writing has been hurt or helped by the lack of a standard format (such as the script standard used in the film industry)?

Erickson: Neither, really. Different formats are developed for different types of games. Books don’t use the same format as magazines for layout and those two are more similar to each other than the writing on Madden is to the writing on Mass Effect. It’s not the difference in subject matter; it’s the difference in what that writing is used for. In Madden, it’s small pieces written for particular situations that are then stitched together on the fly, and so need to live in databases. Excel really is the easiest for handling that. Mass Effect, in stark contrast, is mainly a series of interactive, branching conversations that can only be written in a custom tool built specifically for such things.

Newman: When constructing a new script for a game, what specific elements do you look for to improve the overall gaming experience?

Erickson: Pacing, pacing, pacing. The balance between dialogue and action, the timing of rewards, the dissemination of knowledge and plot at a pace the player can respond to and absorb. Game writing is at least half game design.

Newman: How do you develop these beyond the initial script?

Erickson: Constant review and play testing. Design is testing and iteration. Writing is rewriting.

Newman: In the film industry, it’s common practice for writers to construct detailed backgrounds and back stories to each character in the movie. Is this necessary in the game industry?

Erickson: Depends on the game. We have literally thousands of pages of background details on the project I’m working on now, and most RPGs have at least a solid background story for each character and event. Even when working on NBA Street Vol. 2, I still found it extremely helpful for both myself and the artists to have dossiers on each of the characters. I’m not sure it’s absolutely necessary in a run-and-gun shooter, but it can only help.

Newman: How does a story benefit from having a more fleshed-out cast?

Erickson: You simply can’t write believable lines for a character you don’t know. You must have that voice in your head and be able to have your little schizophrenic conversations with it. Without that, you have just hollow characters mouthing the plot.

Newman: Typically, does a game script contain the same three-act structure of a film? How do you outline the story within a game title?

Erickson: This varies hugely. The three-act structure is a good place to start, but if you’re writing a twenty-hour game you may have more than three acts, or you may, more likely, have several three-act arcs—more like a movie series or a TV show season. Outlining, of course, varies widely. On an RPG, you’re dealing with such a huge beast that the outline itself can be hundreds of pages and take months of work. For a racing game, a couple pages might do it.

Newman: As a video game is interactive (and a film is not), what particular challenges rise when scripting possible pathways for a player?

Erickson: The magic and the frustration of interactive fiction (not games punctuated by cut scenes) is that you must remove the essential tool of traditional writing: the protagonist. The payoff is the trade for player agency, which is everything appealing about fiction in this format, but it’s a jump many writers are unable to make. People will continually wonder how you would make Citizen Kane as a game if you can’t force the character to say “Rosebud”. Well, of course, you can’t. You also can’t make Citizen Kane into a ballet. They are different storytelling mediums and the sooner game writers wake up to that and get over their inferiority complexes, the sooner they’ll be able to start creating great works in their own medium.

Newman: If a game student wanted to embark upon a career of writing for games, where would you direct him or her?

Erickson: The great thing about games right now is that it’s still sort of the Wild West out here. Less so than fifteen years ago, clearly, but a kid with great talent and dedication can still get their foot in the door somewhere. BioWare, for instance, has a couple of fantastic writers that came straight out of school. If you’re talented, I’m not in the slightest interested in your resume. While you’re waiting for that break, though, play as many of the type of games you want to write as you can get your hands on and really analyze what makes them work and what you would improve. Then find something easily mod-able (Neverwinter Nights is great for this and takes no tech knowledge) and practice, practice, practice. Additionally, some of the game design schools are starting to teach game writing, but that’s still fairly rare.

Newman: Do you think this field will continue to grow within the game industry as a standalone job or do you think writing will be viewed as a function of the game designer or creative director?

Erickson: For any company that cares about great writing, this will always be a standalone job and as VO [Voice Over] budgets balloon into the millions of dollars, it only makes sense to pay for great content to put in the actors’ mouths. There is no comparison between a level designer slumming on some dialogue and a gifted writer who’s been studying storytelling for ten years.