Assessment Models

It’s easy for us to be reductionists. We’ve been raised in the Newtonian version of the scientific method, wherein the universe is considered to be a huge mechanical clock, each part separate, discrete, and measurable. So we ask in nearly all situations, “What’s the driving force?” Many of us work in U.S. businesses and are seemingly compelled to ask, “What’s the bottom line?” We feel rushed, impatient. As you read the following chapter, however, see if you can be antireductionistic. Instead of boiling it all down to a facile, and therefore potentially more futile, formula, keep allowing your understanding to become more complex and therefore potentially more creative.

“I think I have seen the western mistake. You are very able to distinguish things, but you are unable to put all things together. Your scientific conceptions, therefore, all have holes in them and numerous incomplete principles are set forth. If you continue in this way, you will never be able to repair this.”

—Hsia Po-Yan, Chinese Philosopher

Although no one would seriously mistake the map for the territory, very often people confuse assessment models with the person who is being assessed. It seems an obvious point that no assessment model, however sensitive or comprehensive, could ever fully capture or display the full range of a person’s actions, feelings, thoughts, potential, and relationships. Nonetheless, whenever we’re lazy we start to use models for labeling people.

I’ve been in so many corporate meetings where people, when identifying themselves, immediately tell the group their Myers-Briggs type so that the audience can know what to expect from them and how to shape their communication to them. In my view, the person might as well stand up and say, “I am an IBM-compatible computer. Do not expect me to be able to connect up with an Apple computer or a washing machine.”

Of course, I’m familiar with the disclaimers that go with many assessment models which state that, in the best of circumstances, these models are only talking about tendencies or preferences. In real life, however, we often forget this and begin to exclusively expect the behavior from the person that the model predicts.

Our expectation does, in my view, influence the person’s behavior and of course frames our observation of the person. Both these aspects lead to a selffulfilling prophecy which, when coupled with laziness, leads us to endorse these models, promote these models, and believe in these models. If you think back to an earlier section of the book in which I talk about hindrances to coaching, you’ll remember that one of the main hindrances to coaching was understanding people as collections of fixed properties with desire attached. The use of assessment models as I’ve described it so far is understanding people in this way. In other words, by using assessment models this way we are reinforcing our understanding of people as things, and this way of understanding makes any effective coaching impossible or nearly so.

Why then am I talking about assessment models, since they seem to be mere flypaper for observations? I claim that it’s possible to use these models as a way of giving form and shape to our observations without limiting the person to the parameters of the model. This requires remembering at all times that an assessment model is a way of speaking about a person—it is not the person—and that our assessment is always up for reevaluation. In the light of subsequent observations or other insights we have about the person, we have to be unattached from our assessment model, and not argue for all the consequences of the model to be present all the time in the behavior, feelings, or outlook of the person assessed.

Even in the face of seemingly convincing statistical analysis verifying the validity of such models, I urge the coach to remember that human beings in every case will exist beyond the borders of whatever model is used to describe them; that a model is at best a well-focused snapshot; and that human beings are living, changing, adapting, and self-interpreting. A whole other way of keeping us awake is to imagine how it feels to be labeled by someone and then to have that person treat us as if that’s all we are.

I guess if we didn’t expect much from ourselves or didn’t want to be counted on for much, it’s possible that we would be comfortable with being labeled. But as soon as we get committed to accomplishing something big, or feel as if we have important ideas to express, or want to make a significant contribution, having been labeled will be an enormous obstacle. For example, you have probably heard about all of the studies that were done of elementary school children in which low-performance students were labeled as high-performance students. This label was given to the teachers who then took actions to bring about the validation of the label of high performance. So even though I understand that in business, for example, it’s important to understand people quickly, I still argue for staying awake in our use of assessment models. That’s because the Pygmalion effect is powerful and pervasive.

While reading this, some people will imagine that I’m saying that as long as we don’t use a negative label it’s okay. Permanently assessing someone as having positive qualities or attributes is just as denigrating to that person as the opposite, because it still assumes that the person is a thing which can be found out about, figured out, and predicted.

One example of this predilection in our behavior was permanently etched into my memory one day when I was waiting at a checkout line in a supermarket. I looked down and read the cover of Life magazine, which depicted a set of quintuplets at age one. Each child was labeled with a name that was meant to capture them, for example, the curious one, the charming one, the intelligent one, and so on. What happens to a child who grows up having been labeled at an early age?

Of course, it’s not only others who label us—we do the same thing to ourselves, as if we could figure ourselves out once and for all and could stop having to learn about ourselves as we went through life. How many relationships, opportunities, and adventures have you neglected or ignored because you labeled yourself as a person who would not begin that relationship, opportunity, or adventure? How much can you set yourself free by releasing yourself from the various ways you’ve labeled yourself? Perhaps worst of all, we determine our own possibilities by the expectations that inevitably flow from self-assessment. Any action that follows such a declaration of identity can at best be a palliative or coping response, regardless of how expensive, energydemanding, or emotionally stirring the activity may be.

What would happen if you became unattached to the labels you’ve given to the people around you, especially to those people you are coaching? In the following presentation of several assessment models, I urge you to keep all of this in mind and to remember at all times that I’m presenting a way of speaking about people that can lead to effectively coaching them.

None of these models captures a person; they only allow for a way of appreciating a person that facilitates a coaching intervention. As a coach, you’ll know that you have not become attached to any particular assessment model when you still find your client mysterious and you still observe unexpected behavior. Finding your client mysterious, then, is an indication that you are doing effective coaching, staying awake as a coach, and not making your client into a thing, and is not an indication that something is missing in your assessment.

For example, when we go to visit a favorite masterpiece in a museum and are able to appreciate it in a new way each time we view it, it means that we are becoming more competent as a viewer of art. This is distinct from figuring out a painting and having our conclusion reinforced each time we look at it.

Probably nothing leads to the resignation we so often find in adults more than the notion that after a certain age, say around 35, we have turned out, we are done, we are the way we are. As I said earlier, it’s probably the coach’s most important task to undo this resignation and this is only possible when the coach has not fallen into it himself.

With all this as essential background, here are three assessment models you can use in your coaching programs. It’s helpful to remind yourself at this point that as a coach you’re working toward building a competence and not toward “The Truth.” The validity of any assessment in coaching is based upon its usefulness—does it enable the client to take action, does the assessment synthesize and bring meaning to the coach’s observations, and so on?

Model one: Five Elements Model

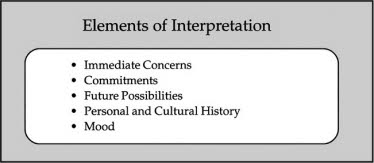

Immediate Concerns

This model (see Figure 6.1) draws strongly from the work of Fernando Flores as presented in his seminars, The Action Workshop and The Competitive Edge Sales Course. There are five areas of observation. The first area is immediate concerns. Immediate concerns are what the client has on his mind at the moment—what is the most pressing problem, either because of its current effects or its potential effects. None of us can listen very well when we have a huge immediate concern, and even when our concerns are small, they still shape how present we can be. Sometimes immediate concerns seem trivial to someone else. For example, a man’s whole day can be determined by the fact that he has a hole in the back of his pants that no one must discover; or a long, leisurely drive in the country can be affected because we hear a strange noise in our car. Once we hear the sound, we stop seeing the scenery.

FIGURE 6.1 Five Elements Model

We can only find out a person’s immediate concerns by asking. We can’t legislate what someone’s concerns ought to be. It’s easy for us to project our immediate concerns onto someone else. What we’re doing in this case is not being present for the other person because of our own immediate concerns. It will probably be a continual challenge for you as a coach to establish the borderline between you and your client. Are these your immediate concerns or your client’s immediate concerns? Is this your mood or your client’s mood? Is this going on with you or with your client? Part of the reason I’m presenting these models is so that you can begin to put some certainty on exactly where the border is.

Commitments

The second area is commitments. Anybody who we coach will be in the middle of dedicating his life to something or someone. Often, this something is not a specific goal or outcome, but rather a particular kind of experience or set of possibilities. It’s easy for nose-to-the-grindstone types to say that such a person isn’t really committed, but I say that it’s always a case of discovering to what or to whom the person is committed, and it’s never the case of whether or not he is committed.

Some of us try to figure out what a person is committed to by watching how he allocates his time, money, and other resources. But you’ll find when you speak to people that many times they will tell you that their commitment lies elsewhere, and that what you’ve been observing is merely the actions they’re taking in order to make something happen that you haven’t observed yet. This can be the case, for example, with a salesperson who is working very hard and making lots of money, but who is doing it so that he can retire at age 40 and sail around the world.

On the other hand, it’s often difficult for us to hear someone say she is committed to something for which she is taking no action, for example, a person who is very overweight saying she is committed to being thin. We may readily conclude that this person is committed to being fat given that the actions she has taken have led to this. I think that it’s a mistake to argue back from the outcomes to determine what the person must have been committed to. This is because a person may be committed to something but be incompetent in bringing about the outcome. Also, by not honoring what people claim to be committed to we are taking over the role of defining what they are committed to, a role that we are neither authorized to do nor capable of fulfilling.

I think of commitment as if it were the engine of a car. It doesn’t matter how powerful the engine is, or how well tuned up it is, or how much gasoline it is getting if it is not connected to the wheels by the transmission. The transmission is a metaphor for competence. This competence takes many forms: sometimes it is skill, as in learning how to fly a plane; sometimes it’s a capacity to observe ourselves and not become defeated by negative emotions or self-assessments. The overweight person, in other words, may be very committed to losing weight but incompetent in bringing it about. Understanding someone in this way will allow us to keep looking for what is missing in his ability to fulfill his intention rather than dismissing him as not being strong enough to fulfill it.

It is American utilitarianism that, in my view, keeps people in the United States concluding that the reason for failure is usually the lack of will. How often have we said to people, “If you want it bad enough it will happen”? We may have come to this conclusion from watching too many interviews with the winner of the Olympic marathon who says that he won because he really wanted it. We don’t interview the person who comes in at 112th place and ask if he really wanted it as well. The tautological argument that the person who wins wanted it the most gets us nowhere because we can only know at the end that people “really” wanted it, and this is too late for coaching. Instead of freeing people to take action, this way of explaining things often leads them into the insoluble dilemma of trying to figure out how to want something more, or into berating themselves for not wanting it enough. It’s like telling people whose cars lack transmissions to keep revving their engines if they really want to get somewhere.

Future Possibilities

Third is future possibilities; what is the person interested in bringing about in the future? As I said in an earlier chapter on language, because we are speakers of a language, we are always simultaneously existing in the past, the present, and the future. We are taking action now to fulfill something we initiated in the past in order to bring about a particular future outcome.

By discerning what future a person is attempting to generate, we can begin to make a different kind of sense of the actions she is taking presently, and perhaps we can even think backwards and begin to discern the origins of her actions.

Given that people are always projecting themselves into the future, any request or suggestion we make will be considered to be either a support or a detriment to bringing about this future. All this is done quickly and without conscious deliberation. A person would only be aware of liking a request or suggestion and being drawn to it or, on the other hand, finding it uncomfortable or distasteful in some way. That’s because in our day-to-day consciousness we are not making decisions based upon weighing future consequences. It’s more that we are coping with each situation, relationship, and conversation as it comes along in the light of what we set out to do in the past.

If you observe yourself for a few days you’ll see that this is in fact the way you move through life. Of course, this is both good news and bad news. The good news is that we don’t have to stop and weigh all the actions that we’re taking in the light of future consequences. The bad news is that it’s easy for us to become automatic in our responses and consequently to miss being present with what we are encountering.

This phenomenological way of describing our day-to-day life does away with the commonsense notions many of us have about motivation. The problem is that, in the middle of life, we forget what is supposed to be motivating us. How often have we remembered after we ate the chocolate cake that we are supposed to be, according to our doctor, on a diet? Or perhaps it’s according to our wish to fit into our summer clothes. Somehow this “motivation” fades into the background in our day-to-day coping. One solution is to threaten others with such a dire outcome that they would not dare forget the consequences of noncompliance. And I suppose this could work as long as you are able to keep finding fresh ways to threaten people, because threats certainly do become stale when they are repeated again and again. Even if this kind of motivation were positive, that is, providing a reward instead of a punishment, the person being motivated would still be reliant on the continuation of the reward to support him in accomplishing what he set out to do. Such a scheme never leaves the person more competent, but rather leaves him searching forever for a lasting motivation which cannot exist.

It may be obvious that the important role of a coach is to be someone who can remind us of what we set out to do and can work with us to keep building a way of observing and acting that is consistent with our projects. It is the job of the coach to leave the client able to fulfill the future that the client intends. One of the first steps in bringing this about, of course, is to find out what future possibilities our client has in mind—thus its placement in our first assessment model.

Personal and Cultural History

Fourth is personal and cultural history, which I suppose is self-explanatory. It simply means that each of us has had a different history of interactions with people and circumstances, which has influenced subsequent ways we respond. All of this takes place within influences that are particular to individual cultures. Regardless of how hard we try, none of us born and raised in the United States will ever really understand what it is to be Japanese. And a Japanese person couldn’t even tell us what it is to be Japanese in a way that would allow us to become Japanese ourselves. Perhaps it is through the artwork of a particular culture that we are most able to understand what it is like to be a member of that culture. Such a study will take us beyond clichés or stereotypes into the otherwise inexpressible core of a particular culture.

Mood

Fifth is mood, which we spoke about briefly in the section “What Is a Human Being?” In this model, which is based upon the work of Solomon (1983), I mean it in a slightly different way. I usually don’t make any attempt to have my models be consistent with one another. If they were, it probably would be possible to collapse the models down into one and a coach would lose the power of assessing the client from various perspectives simultaneously. It seems to me that it is the job of a coach to understand the client in more and more ways rather than in fewer ways, even if fewer ways would be simpler for the coach.

Mood is the semipermanent emotional tone within which a person exists. It gives meaning to present circumstances, defines our engagement in them, and colors our view of the future as well. In this discussion, I will speak about three aspects of mood: the judgment that is the basis for the mood, the actions that are consistent with the judgment, and finally, how the mood maintains our self-esteem. In some cases the maintenance of self-esteem may seem strange, but we human beings are always attempting to find ways of making sense of what we encounter, giving ourselves a sense of power when circumstantially we have none, and maintaining our sense of dignity even when, outside of the internal logic of the mood, none of it makes sense.

Understanding a mood, then, is similar to understanding a person. The task is to understand the mood on its own terms and not fall into dictating what it ought to be or must be. I’ll give some examples of moods that are quite prevalent in business and are difficult to deal with. Some readers may find these moods too negative. I’m not claiming that they are the only moods present in business, but they are present enough to be used as examples to illustrate how mood works.

I’ve divided this set of moods into two parts, the moods of people who feel as if they are superior to others and the moods of people who feel as if they are inferior to others. Of course, there is the paradox that people feel as if they are inferior because they are asserting their inferiority in order to feel superior. Some people have also told me in discussions about these moods that people who assume superior moods are really attempting to make up for an inner sense of inferiority. To keep things simple though, and to be able to present it in a book, I’m going to maintain the distinctions of superior and inferior in this discussion.

Superior Moods

Skepticism

The judgment is “I doubt.” In healthy cases it ends there. In more pathological cases it becomes insatiable doubt. There has been a strong movement in philosophy called skepticism. David Hume is perhaps the strongest proponent of this view. Philosophers following him have never been fully able to successfully refute his contentions, so nowadays, most philosophers don’t try. Perhaps nonphilosophical skeptics know in some way that there cannot be a final absolute answer to any question and that by continuing to ask they will keep their opponents off balance.

The behavior is to question. Skepticism maintains self-esteem by disguising itself as sophistication. I call it pseudosophistication. Skeptics take themselves as experienced, knowledgeable, or seasoned, and attempt to inform others of these qualities by the number of, and insightfulness of, their questions. Is there any reader who has not encountered a skeptic? If so, I would be surprised.

Here are some examples of professions, roles, historical figures, or famous people who stereotypically embody skepticism: newspaper reporters (at least starting out, later they move to cynicism), scientists, parents of teenage children, accountants reviewing expense reports, IRS auditors, purchasing agents, bartenders on Wall Street, police officers, and high school principals.

Cynicism

Cynicism is the judgment that no one and nothing is worthy of respect. Cynicism is harsher than skepticism in that cynics make judgments about the person, not just the information he is providing. The behavior of cynics is to insult, disparage, and put down everyone.

Cynics do not exclude themselves from their own judgment. You’ll recognize cynics because they say things like, “Well, yes, he does look good on the outside, but we all know that on the inside he is out to crush everyone who gets in his way, just like all of us.”

Cynics maintain self-esteem the same way skeptics do, that is, by taking their cynicism as sophistication. The capital of cynicism in the United States is Washington, D.C. Being close to the government and hearing the promises of administrations being made, Washingtonians see the promises unfulfilled time after time and conclude that none of these political types is worthy of respect.

Cynics are always looking for the secret motivation behind even the most laudable actions. No one is good enough for a cynic. Human foibles of any size are enough evidence for a cynic to convict anyone of being guilty of a crime, which necessitates the cynic’s withdrawing of respect.

Here are some examples of cynics: older newspaper reporters, Mark Twain, Sinclair Lewis, William Faulkner, many political consultants (e.g., Lee Atwater), people involved in organized crime, strident promoters of laissez-faire capitalism, the character portrayed by Michael Douglas in Wall Street, many of the movies of Scorcese (e.g., Goodfellows), the editors of many supermarket tabloids, and anyone who attempts to make a living by exploiting the weaknesses of others. This includes some people in management as well as some of the more obvious examples like drug dealers and bookies.

Resignation

This is the judgment that “nothing new is possible for me.” The behavior of resigned people is to withhold commitment and to stake out a small, controllable territory in which to become very comfortable. Many times resigned people can be initially deceiving, because their resignation is covered up by a thin veneer of optimism. The veneer falls away, though, when a resigned person is asked to take action that can result in an observable outcome measured by some degree of change. At this point the resigned person will find many ways to show why the change is not necessary and may, in fact, be harmful, or may find a more politically powerful ally to make sure the action won’t occur. Of course, no one in an organization can say that he or she is resigned, so the maneuvering and withholding of support is done underground, but the consequences are nonetheless real.

Resignation maintains self-esteem by posing as pseudowisdom, that is, wisdom that sees justification only for everything to continue as it has. Resigned people think of themselves as having profound understanding based upon firsthand, long-term experience. They forget that it’s often because of their own resignation that the change effort of others or even themselves is thwarted. Besides, changing is uncomfortable and uncertain. What has happened up until now is familiar, comfortable, predictable, and controllable. Any of you who has ever attempted to bring about change in an organization or a relationship probably has encountered some resignation. What to do about it, I don’t know. I’ve given up. Just kidding.

Here are some examples of resignation: Chekhov, Kafka, many people involved in large bureaucratic organizations, postal workers, factory workers, and people who work for the federal government.

Inferior Moods

Frustration

Frustration is the judgment that “I must make something happen and I cannot make it happen.” The commitment is one that I cannot walk away from and the circumstances make it impossible, as far as I can tell, to fulfill the commitment.

A physician working in an inner-city emergency room where people sometimes die while they’re waiting for treatment is a good example of frustration. The physician cannot just walk away from the seemingly endless parade of wounded and drug-ridden bodies and, at the same time, she doesn’t seem to have any power to provide quick and sufficient care for the hordes of people waiting, or any power to affect the system that keeps people cycling through the emergency room.

Dedicated workers in large corporations who are attempting to bring about major change often find themselves frustrated. In fact, I would say that much of the good work done in organizations is done by people who are frustrated. That’s because the behavior characterized by frustration is to work very hard, and to complain about the hard work and the circumstances that make success seemingly impossible, but, like Sisyphus, to never give up. Frustrated people are not going to let the circumstances of the system beat them. They keep going, sometimes to burnout and beyond.

Here are some examples of frustration: Wile E. Coyote, the Oliver Sachs character in the movie Awakenings, the mayors of major U.S. cities, teachers in public school systems, and the coach of the Chicago Cubs.

Resentment is the judgment that “something unfair has been done to me deliberately by someone else and I have no power to do anything about it.” The judgment of powerlessness is what gives resentment its unique character, because someone in the same circumstances who judged that he has power would instead be in a mood of anger.

The behavior of resentful people is to put distance between themselves and the object of their resentment and then to begin to plot covert revenge—also known as sabotage. Angry people, on the other hand, seek a confrontation with the object of their anger and plan to get justice in a face-to-face encounter.

The sabotage of resentful people can be shown in many different ways, including many of the passive-aggressive behavior patterns that show up in business, for example, forgetting meetings, slowing work to a near crawl, misplacing files, and spreading negative gossip.

The emotional distance that is part of resentment is also easy to observe; often it takes the form of a precise, brittle politeness or a coldness that is reminiscent of stepping into the Arctic Ocean. Given that the resentful person does not seek to bridge the distance, many times the person being resented is at a loss to explain or understand the emotional distance. Often, attempting to uncover it only increases the distance, which can be readily covered up by denial and by projecting the distance-making activity onto the person being resented. Resentful people are avengers for justice. This is how the mood maintains self-esteem. Even if it takes a thousand years, the resenter will make sure that justice wins out.

Here are some examples of resentment: the daughters in Shakespeare’s King Lear and Shylock in The Merchant of Venice.

Guilt

The all-American mood, guilt, is last in our listing. I call it the all-American mood because American culture is a particularly fertile environment for guilt. Guilt is the judgment that “I have done something to injure someone and I can never make up for it.”

The behavior of guilty people has three parts. First is apologizing a lot. Guilty people will apologize about the intemperance of the weather, traffic jams, and the high prices in stores. Second, guilty people work really hard to try to make up for what they did, saying things like, “I feel so terrible about making an addition mistake on page 312 of the budget. This year I will give up my vacation, send my children to childcare, and set up a cot in the accounting office to make sure that I don’t make any mistakes this time.” Last of the actions of guilty people is emotionally punishing themselves. How much? As much as is possible this side of death, because death would preclude the possibility of further punishment.

In the United States, guilt takes on at least three different forms that I know of. There is guilt that has to do with relationships—“I gave up all of my life to send you to college and this is how you treat me. You never call or visit. What kind of a son are you anyway?” There is guilt that has to do with sex—it’s a sin to think about it, it’s a sin to plan it, it’s a sin to do it, and it’s a sin to remember doing it. There is guilt that has to do with work—“I’m so sorry, dear, that I have to leave you while you’re giving birth to our first child, but there are some really important reports I have to get out of the office,” and “Sorry to leave Thanksgiving dinner, but I really must check up on my voice mail.”

Why would anyone take on this mood when it seems so painful? Well, first of all, guilt gives people a false sense of agency. Feeling bad about something that has happened gives a guilty person the sense that he or she could have done something about it. Thus, the secret service agent assigned to protect John Kennedy still feels guilty because he feels as if he could have been one second faster and saved the president’s life. The examples above of people apologizing for weather, traffic, and prices are another variation on this theme of false agency.

Guilty people are also the most self-righteous people. “I know I did it, but at least I feel bad about it. There are lots of other jerks doing it and not even feeling bad about it.” You can be assured then that the people who are acting the most self-righteous are simultaneously feeling the most guilty.

Here are some examples of guilt: Oedipus, Hawthorne’s Hester Prynn and the minister in The Scarlet Letter, and St. Augustine.

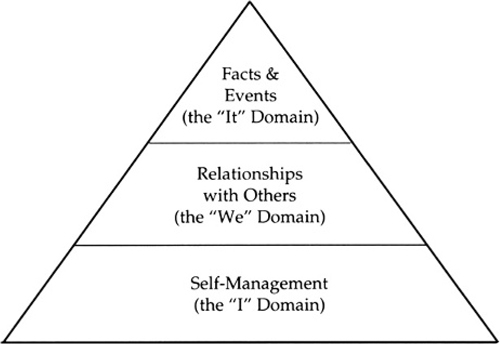

Model Two: Domains of Competence

This model (see Figure 6.2) is based upon the work of Habermas, although he might not recognize it. Its premise is that in order to accomplish anything of substance, we must be minimally competent in each of the three domains depicted in the pyramid. Each of the domains requires a different kind of thinking and, consequently, different people will gravitate toward different domains.

FIGURE 6.2 Domains of Competence

I’ll begin talking about these domains by first explaining the bottom one, Self-Management. Self-management occupies the foundation position for the pyramid because it is the basis for the others, but please do not think that because it is the most important it is the only domain in which we ought to become competent.

Self-management means that we follow through on what we said we would do, we arrive on time, we understand the standard practices of the organization for which we are working, we present ourselves and our ideas appropriately, and we don’t allow any personal issues or concerns to impinge on what we said we would do.

The skill of self-management is based upon our ability to observe ourselves and the effects of our actions on the outcomes we intend and on the people with whom we relate.

Although they are often confused, self-management is distinct from self-justification, which is the story we tell ourselves and others when we don’t accomplish what we said we would. In fact, people who are skillful in self-management can readily sense any iota of self-justification creeping into their thoughts or into their conversations and delete it forthwith.

Here’s a list of the qualities and skills of self-management:

- qualities: vision, passion, integrity, trust, curiosity, daring

- skills: self-observation, self-knowledge, self-management, self-remembering, self-consistency

The middle third of the pyramid is labeled Relationships with Others and refers to our capacity to develop and maintain long-term, mutually satisfying relationships. Most readers probably understand that it’s only through this capacity that we have any chance of being successful in any organization. It is not possible for any person, regardless of his capacity for work, to do everything, and it is always the case that any one person’s thinking is limited.

The essence of successful relationships is openness and appreciation. By openness, I mean allowing ourselves to be influenced by the ideas, emotions, and world of a person with whom we are relating.

For those of us who are saying to ourselves that this excludes most of our relationships, I wonder what these relationships are like. Are we positioning ourselves as heroes in the relationship, as the ones who have all the wisdom, as total givers and providers? If we are relating in this way, it’s very easy to slip into a mood of arrogance so that we are no longer really relating at all, but only proclaiming our own notions and building our own empire. You’ve probably noticed people around you doing this and, even if they are in positions of apparently irresistible power, they are generating an environment of resentment around themselves that makes their work more difficult than it has to be and less effective than it could be.

Appreciation means that we understand the validity of other people’s worldviews and take it on as our task to see to it that there is a forum for the expression of those worldviews, if only in our own relationship with those people. Appreciation means that we are not trying to bring the other person around to our way of seeing it, or letting him in on how it really is according to us, or trying to get him to do what we want him to do.

For example, those of you who have children can clearly see that children under age seven live in their own world which is only tangentially connected to the adult world in which most of the readers of this book live. When we attempt to take apart our child’s world with the norms, logic, and customs of the adult world, we are in fact damaging our relationship with that child. We don’t have to worry; life will soon enough present its constraints to our child. There’s no need to do it preemptively, even if that was done to us by our parents.

Dealing with the world of relationships means that in order to be successful we have to learn about emotions as well. Emotions are what bind us together. Attempting to have even the most professional relationships without emotion is like attempting to build a brick edifice without the use of any cement. It may stay for a while, but it will not hold up under pressure or when any significant force is applied to it.

Whenever we try to step out of the world of openness, appreciation, and emotion in our relationships with people, and attempt to speak with the language of one of the other domains of competence, we are ensuring the demise of the relationship. A sure sign that we are doing this is when we attempt to be right in an argument rather than trying to understand.

Here’s a list of qualities and skills of relationships with others:

- qualities: empathy, reliability, openness, optimism, faith

- skills: listening (teamwork, real concerns), speaking (possibilities, inspiration), setting standards (developing others), learning, innovating

The third layer of the pyramid is called Facts and Events and refers to our capacity to understand mechanisms, processes, statistics, systems, and models. This is the layer with both the most experts within it and the most fear attached to it. There are many of us who don’t want to enter this domain at all and wish the experts would just handle it all for us.

The problem is that if we don’t have a rudimentary understanding of the domain, we can’t understand the decisions being made on our behalf and we will have a difficult time in our attempts to improve the systems and organizations of which we are a part.

On the other hand, some people of high technical expertise attempt to ignore the other two domains of competence. Sometimes this works if the expertise is vital and present in only a few individuals. The expertise, however, may become less valued and, given that this expert has not developed relationships successfully or managed himself very well, there will be very little chance of him finding a place within the organization at that time.

Here’s a list of the qualities and skills of facts and events:

- qualities: rigor, objectivity, persistence, creativity, focus

- skills: analyzing (inhibiting factors, sources), predicting (long- and shortterm effects), simplifying (Occam’s razor), building models, organize/ prioritize/release

Sometimes strength in one domain is used to try to cover up a weakness in another domain. For example, some people try to have relationships or justify not having them by insisting that other people maintain the same values and standards as they themselves have. This is an attempt to have relationships work by using one’s capacity within the self-management domain.

We probably all have met people who are charming and politically sensitive who acquire positions of authority and prestige because of their ability to succeed in the relationship domain. Such people will try to avoid making specific promises because they are weak in self-management and will call on others to take care of any technical situation that arises in the domain of facts and events. But can these people deal with the sometimes harsh facts and events that present themselves? And can they sit down and do the long, tough, sometimes boring work required to really learn something of value?

By attempting to steer the world from within only one of the domains, we will minimize our chance of success and will make what was once our strength into a blindness that many times leads to dismal failure.

Model Three: Components of Satisfaction and Effectiveness

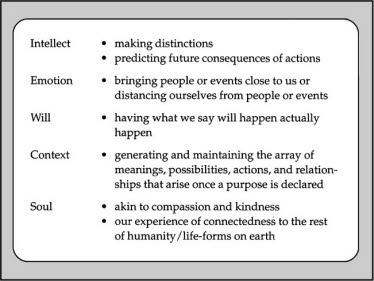

In a way, this is the simplest model (see Figure 6.3). It is a listing of the competencies necessary to be both satisfied and effective. They are specific to the area in which we are working so that intelligence, for example, in fixing a car engine is not the same as intelligence in playing the violin or baking a soufflé.

The so-called intelligence quotient test that many of us took as children measured very specific types of intelligence that have to do with, it seems to me, success in a very narrow band of activities. I wonder how someone whose intelligence was in choreographing beautiful ballets would do on a standard

I.Q. test?

You can use my definitions of these competencies when observing coaching clients, when assessing where breakdowns are occurring or are likely to occur for a specific person, or when determining what the subject of a coaching program could be.

FIGURE 6.3 Components of Satisfaction and Effectiveness

Intellect

By intellect, I mean the capacity to make distinctions and predict the future consequences of actions. That is to say, someone can see that if one course of action is taken today, six months from now such-and-such an outcome will occur. This description attempts to include both people who build logical step-by-step processes leading to conclusions and people who make intuitive leaps that can also turn out to be accurate. I’m also attempting to describe intellect in the most general way without trying to describe the various processes that go into the capacity. For example, knowing many distinctions is a product of learning, and predicting future consequences of action has a lot to do with understanding the interconnectedness of systems. In any case, regardless of the origin, someone who is strong in intellect will have the two capacities mentioned.

Emotion

Emotion here means something very different from our usual understanding of the term. In this model, emotion means the capacity to bring people and events close to us when appropriate and to distance ourselves from people and events when appropriate. It’s this telescoping ability that I’m referring to as competence in emotion. Some people have what I call fixed emotional distance. That is, they may hold everything very close to themselves, thus diminishing any sense of perspective, or they may view even the most intimate experiences of life from a great emotional distance and are not touched by birth, death, or love. In business, sometimes it seems as if the latter emotional distance is the one that is most fitting. It leads, however, to a draining of interest in any topic, the inability to inspire anyone else, and in the end, a weakening of resolve.

Will

By will, I mean the capacity to make what we intend to happen actually happen. People of extraordinary will, of course, can have their will seemingly exist in other people and sometimes even at a great distance. Founders of the world’s great religions are the epitome of this. None of them is on earth now and yet millions of people are still following through on what each one intended to have happen.

Context

Context is the ability to build and maintain context. Yes, I know this is tautological, but let me tell you what I mean by context. I mean the array of meanings, relationships, actions, and possibilities that arise once a purpose is declared. Purpose is our dedication to the fulfillment of people and causes beyond our own survival and comfort and the survival and comfort of our families.

For example, once I say that my purpose is to improve education for children in my city, I immediately have a different meaning for my own education—backward and forward in time—a different relationship with students, parents, teachers, administrators, and a whole long list of potential actions and new possibilities that I can address.

Our capacity to design a purpose and then bring our own life into alignment with it is what I mean by context. In my definition, context is never a given; it is generated by individual people. And because of that it is often a missing component in people’s lives. In fact, many of us never even speak about what our purpose could be and instead work only on coping with day-to-day situations. This lack of context, moreover, becomes readily apparent in moments of crisis when we don’t have any criteria by which to make decisions or when we are in an ethical dilemma and don’t know what to do. It becomes most inescapable as we near or face our own death.

Soul is the last competency listed in this model. First of all, I don’t presume to precisely define what I mean by soul, but it’s something like kindness, generosity, compassion, and connectedness to the rest of humanity. I’m trying to point to that quality in people who have what we call great souls.

This element is the one least likely to show up in performance reviews and, at the same time, it’s the one we find most inspiring, powerful, and admirable.

In business, it’s been the case up until now that people have been able to get by because they have had strong intellect and strong will—the same qualities, by the way, that have long been developed by the military. Living life stressing only these two elements has big consequences—one of them being that the game, which is all-consuming while being played, immediately becomes pointless as soon as we step away from it. Many workers experience this during long vacations or shortly after retiring. Also, stressing will and intellect presupposes a fixed emotional distance which leads to much separation between such a person and family, friends, and colleagues. See the movie The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit for a graphic example of this. Developing our capacity in all five of these elements will make us more able to do our work and will also give us a greater sense of fulfillment while doing it.

Using These Models

It seems common sense to me that we find something only when we are looking for it. For example, we don’t notice how many red Hondas we’ve passed on a particular day’s drive unless we are setting out to count them. It’s not that our intent to observe brings the cars into existence, it is rather experientially the case that the cars aren’t there for us until we intentionally direct our attention toward them.

The point of having presented these assessment models is to allow the reader to make observations with them in mind. When we begin to observe differently, new horizons of possibility begin to arise. In terms of coaching, this means that we discover new, powerful explanations for behavior and, more importantly, new openings for coaching interventions. I have often seen coaches dumbfounded because the models of observation they were using could not adequately account for the behavior they were observing, or made it seem impossible for any intervention to occur. For example, some coaches will say, “Well, there’s nothing I can do until he gets himself motivated,” or “Nothing can be done; she just doesn’t have it.” Almost always I have observed in these situations that the coach only understood the client as some kind of extension of the coach, which means that unless the client saw things and did things the same way the coach did, the client remained an impenetrable enigma. In such cases, I recommend that coaches employ another model, speak with a third party, or at least recognize the limitation of their own interpretation and not insist that their own understanding is complete, and consequently there must be something wrong with the client. You can imagine your own frustration if you visited a physician who could not adequately diagnose and prescribe for an ailment you suffered from and instead wrote you off as an insoluble case, a hypochondriac, or a malingerer. None of these conclusions would assist you in becoming healthy. I am sure we would hope that a physician who found himself in this situation would do additional research, call in someone with greater expertise, or interview us at greater length in order to find additional clues to the resolution of our ailment.

In a similar way, as coaches we must not let initial confusion or frustration prevent us from coming to a complete enough understanding of our client for coaching to begin. Here are some practical ways you can go about using the models presented to understand your clients.

Principles of Observation

- Observe your client in a variety of situations, if possible. This will give you the chance to begin to notice behavioral and speech patterns. If our observations are limited to a narrow band of activity or to a single event, we won’t be able to assess the degree of flexibility in our client’s response.

- Prepare yourself for observation by reviewing the assessment models and resist the temptation to make conclusions based on memory rather than on real-time observations.

- Ask questions of your client in order to reveal more of her structural interpretation but not to verify the assessments you’ve made. For example, if you’ve observed a negative mood in your client, I urge you not to ask a question such as, “Don’t you think your mood is cynical?” because that question will almost invariably lead to a defensive response from your client. Instead ask a question that could clarify whether or not the judgment you assume your client is making is the actual judgment she made. For example, with the client who you are assuming is cynical, you could ask, It seems to me that you are not going to let those folks we just met with pull the wool over your eyes. Is that right?” If the client answers yes, that gives you more data with which you can verify your preliminary assessment, that some degree of cynicism is likely present.

- Evaluate the validity of your assessment by using it to explain the behavior you’ve observed. Predict future actions, provide an opening for your coaching intervention, while simultaneously maintaining a dignified, respectful relationship with the client.

- Always keep your assessments open for reevaluation and keep reminding yourself that there’s much about your client that will continue to remain mysterious. The mysterious unknown and perhaps unknowable aspects of your client arewhat allow for change, improvement, and even transformation.

Applications of the Models to our Case

To further clarify my explanation of these models, I will apply them to the case study we have been following.

Model One: Five Elements Model

Immediate Concerns

Bob’s immediate concerns were different at each of our meetings. Sometimes he was experiencing the pressure of deadlines. Sometimes he was distracted by the preparation he needed to do for a big presentation. At other times, his immediate concern was whether he could get home in time to watch his son play Little League baseball. We ought never assume that we know what someone’s immediate concerns are, but rather we should ask.

Commitments

Bob was committed to his wife, his two children, and their safety and well-being. He was also committed to the success of his team at work and the overall success of the company. He also was committed to his exercise program and his participation in his church.

Future Possibilities

The possibility that Bob saw most clearly was that he be promoted to an executive level so that he could enjoy the security and financial rewards of that position. He also was dedicated to the possibility of his children having the opportunity to attend college, travel, and be launched into the adult world. He saw his life beyond his work career as retirement in a warm-weather environment where he would have access to many outdoor activities.

Personal and Cultural History

Bob grew up in southern California, went to UCLA, and got his degree in accounting. He had been married for 15 years and had an 11-year-old son and a 7-year-old daughter.

Mood

For the most part, Bob found himself in the mood of frustration. He really wanted to be promoted but he couldn’t figure out how to make that happen and he wasn’t willing to give up.

Model Two: Domains of Competence

Self-Management

This was a very strong suit for Bob. He was clear about where he wanted to go and was disciplined in his approach. He was reliable, did quality work, and could be counted on to be a steady influence during crisis. He was organized and prepared himself well for meetings.

Relationships with Others

From everything I have said so far you can probably tell that this is where Bob needed the most development. He had to expand his ability to understand the varying concerns of the people around him. He had to find ways to communicate in a convincing way to people above him in the organization and he had to learn to become more competent in dealing with the political forces at play within his organization.

Facts and Events

By any standard Bob was an expert in his field. He had graduated at the top of his class and kept current by reading appropriate journal articles, speaking with others in his field, and occasionally attending seminars. He could quickly read through financial statements and determine the soundness of what was presented and what additional research had to be done. In everything that I could find out, no one had ever complained about the accuracy of his final reports.

Model Three: Components of Satisfaction and Effectiveness

Intellect

Bob had a strong intellect in accounting but had weaker intellectual capacity in relationships. He was not very sensitive to nuances of meaning, subtle emotional cues, or to the unspoken threads of meaning lying just beneath what was being said.

Emotion

Bob was very good at keeping an objective distance when conducting his financial research and writing his financial reports. However, he did not show a similar objectivity in assessing his own performance in relationships at work. In this realm he was more easily offended, was often off balance, and sometimes had difficulty in recovering after a real or imagined insult.

Bob had a very strong will. He continuously demonstrated great determination in what was important to him. As I said earlier, he put himself through school and got his advanced degrees and certifications while maintaining a full-time job.

Context

Bob had never, previous to our coaching, had a serious conversation about context. The closest approximation was some unfocused ideas about his purpose in life which he had picked up from church and from reading some inspirational biographies.

Soul

Kindness and compassion were very important to Bob and on many occasions he wouldn’t take actions when he felt they violated these two values. Intellectually he understood his connection to everyone else but this was not real for him as a feeling or an experience.

Suggested Reading

The more profoundly and systematically we understand someone, the more effective and lasting our coaching can be. The listed texts propose many different models. All are helpful—none alone is the answer.

Brown, Daniel P., Jack Engler, and Ken Wilber. Transformations of Consciousness. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1986.

A compilation of essays in transpersonal psychology, a discipline dedicated to unifying Western and Eastern (hemispheres, not New York and San Francisco) traditions of human healing and transformation. Especially helpful are the three chapters by Wilber outlining his model for the stages of individual human transformation. His model includes the essential issues for each stage and helpful interventions for each. Provides a coach with many ways to understand the pain and possibilities of particular clients who may be quite different from him-or herself.

Dinnerstein, Dorothy. The Mermaid and the Minotaur. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

The author delves deeply into how the roles assigned to women and men in our culture lead to profound suffering. Challenging. Often irresistible in its argumentation.

Dreyfus, Hubert L., and Stuart E. Dreyfus. Mind over Machine. New York: Macmillan, Inc., 1986.

A book about the limits of computers that sheds light on how people learn. Especially useful distinctions regarding the stages of competence.

Durrell, Lawrence. Justine. Vol. 1 of The Alexandria Quartet. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1957.

A sensuous series of four books telling the same tale from four perspectives. An unforgettable experience of the seduction and pervasiveness of interpretation. Wonderfully written. A novel, not an explanation.

Durrell, Lawrence. Balthazar. Vol. 2 of The Alexandria Quartet. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1958.

Durrell, Lawrence. Mount Olive. Vol. 3 of The Alexandria Quartet. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1958.

Durrell, Lawrence. Clea. Vol. 4 of The Alexandria Quartet. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1960.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. New York: The New American Library, 1964.

The author shows her brilliant understanding of human life by creating many unforgettable characters. An incredibly moving story of loyalty and integrity.

Erikson, Erik H. Childhood and Society. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1950; reprint, 1985.

How does a culture ensure that children will be prepared to fill the roles of adults? Erikson addresses that question and presents many insights into the forces underlying behavior, including a well-known listing of stages of psychological growth. Fascinating and useful.

Erikson, Erik H. The Life Cycle Completed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1985.

A pithy summary of Erikson’s life work. Captures in two charts his decades of research and experience in how a human life unfolds, develops pathologies, evolves, and completes. Brilliant and elegant.

Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books/Doubleday, 1959.

The way you observe will be altered by reading this sociological tract, which studies signs and artifacts for the notions of self that underlie them.

Goleman, Daniel. Destructive Emotions: A Scientific Dialogue with the Dalai Lama. New York: Bantam Books, 2003.

Presentation of a comprehensive dialogue on the topic between important researchers and teachers from the Eastern and Western traditions. Cogent. Insightful. Worthy of thorough study.

Goleman, Daniel. Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam Books, 1995.

A book of colossal importance. Makes the case for bringing the study of emotions into the workplace and into our schools. Clearly written. Well grounded. Vital for all coaches to read.

Harré, Rom. Personal Being. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

A learned text that proposes understanding people as the intersection of many conversations, some public, some private. A starting place for appreciating the way language individually shapes human beings.

Heidegger, Martin. The Basic Problems of Phenomenology. Translated by Albert Hofstadter. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1982.

Probably the problems won’t seem basic to you, but Heidegger forms his text as a response to the founding issues of Western philosophy (he calls them the basic problems). A closer and more expansive presentation of the ideas in Being and Time.

Keen, Sam. The Passionate Life. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1983.

The author proposes understanding life as a series of roles/stages that form around our relationship to love and eros. Very accessible and liberating.

Keleman, Stanley. Emotional Anatomy. Berkeley, CA: Center Press, 1985.

The author proposes that with education, an observer can comprehend the emotional life of an individual by studying his body. Full of dramatic illustrations. Important competence for any coach. (See also Kurtz and Prestera, The Body Reveals.)

Kroeger, Otto, and Janet M. Thuesen. Type Talk. New York: Dell Publishing, 1988.

A popular introduction to the nearly ubiquitous (in business) Myers-Briggs method for understanding individual preferences and tendencies.

Kurtz, Ron, and Hector Prestera. The Body Reveals. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

A handbook full of examples and illustrations that argues that an observer can determine the core issues of someone by assessing his body with a particular set of distinctions. A vital text for any coach who doesn’t want to be fooled by what people say about themselves. (See also Keleman, Emotional Anatomy.)

Miller, Alice. The Drama of the Gifted Child. Translated by Hildegarde and Hunter Hannum. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1983. (Originally published as Prisoners of Childhood. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1979.)

The author, noted in the field of childhood development and trauma, explains the roots of narcissism and depression, perhaps the two most prevalent emotional disorders in U.S. culture today. A small gem.

Miller, Alice. For Your Own Good. Translated by Ruth Ward. New York: Basic Books, Inc./HarperCollins, 1992.

Violence is taught. Young children (and their bodies) are the students, misguided adults are the teachers. The subtitle says it all: “Hidden Cruelty in Child-Rearing and the Roots of Violence.” Disturbing and convincing.

Schutz, Alfred, and Thomas Luckmann. The Structures of the Life-World. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1973.

A rigorous, phenomenological examination of the origin and continuation of the structure of everyday experience. Closely argued. Written for a professional (philosophical) audience.

Solomon, Robert C. The Passions. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1983.

The author claims that emotions are judgments that we make, not mysterious forces that overtake us. Provides an extensive background for understanding his assertions and an encyclopedic listing of emotions from A to Z. The last section presents many common self-defense mechanisms. Belongs on (or near) the desk of every working coach.

Wilber, Ken. The Atman Project. Wheaton, IL: Quest, 1980.

A detailed survey of the stages of psychological and spiritual growth. Cross-references Western psychological and psychoanalytical models with Eastern spiritual traditions. Comprehensive and exhaustive. Huge bibliography.

Wilber, Ken. No Boundary. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1979.

A short, elegant text that quickly gets to the nub of human suffering and proposes many practical ways to deal with it. Lucid and friendly.