To Market or Not…

Any business text will quickly identify the importance of marketing in a commercial project, and so will I. But here the issues are a bit more complex. It becomes exceedingly important to delineate not only the market opportunity but also the appropriate sales engines—including startups new divisions, franchising, licensing, joint ventures, and so on—as platforms to recognize its potential throughout the product lifecycle.

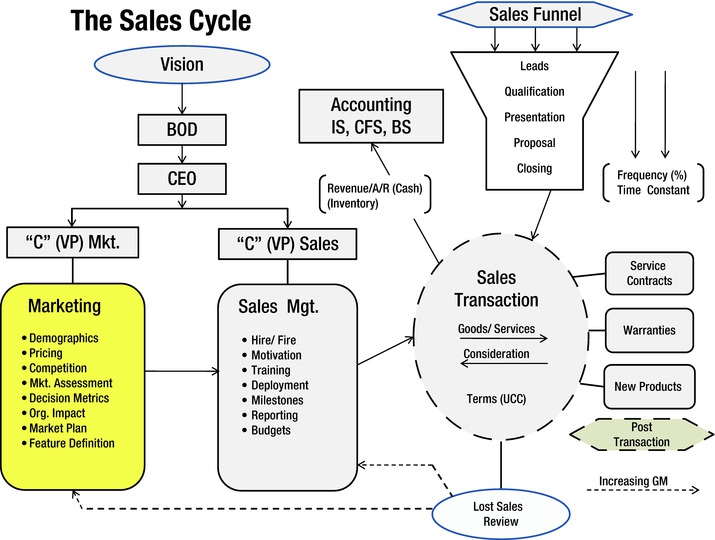

Marketing is a critical aspect of understanding (and acting upon) how a given product or service integrates into the customer’s perceived needs. It is not a singular function but rather a range of interactions both inside and outside of the organization. Marketing’s position may be best observed in Figure 7-1.

Figure 7-1. Sales/marketing interaction

In ocean sailboat racing, it is interesting to observe the role of the skipper, also known as the helmsman. Usually, it is the owner or a similar commanding figure exercising the helm, looking quite authoritative and sometimes shouting orders for sail changes or directional headings with great fanfare. It’s really quite a photo op, and the implication is that the winning strategy is derived from that behavior.

The unsung hero in this drama is the tactician, who sits below the skipper and is constantly calculating wind direction, sea forces, and relative boat positions. The tacticians are typically hunched over a laptop or other computing device and succinctly issuing alternatives for the captain and crew to follow. The race is usually won by this function.

So it is with a corporation, where the CEO and CMO (Chief Marketing Officer) play analogous roles of the skipper and tactician on the boat. Winning has something to do with the directions set by marketing.

In the period of 2005 to 2009, there were a series of devastating articles predicting the demise of traditional marketing. Fredrick Webster, Jr. and others published an article in the 2005 Sloan Management Review entitled the “The Decline and Dispersion of Marketing Competence.” In it, they reported corporate CMO tenures of less than two years. Marketing budgets fell to single digits and the percentage of revenue reported and staff turnover was rampant. In the McKinsey Quarterly of the same period, half of a group of European CEOs were “unimpressed by their CMO’s performance and felt they ‘lacked business acumen’.” In a similar article published in the Sloan Management Review (Summer 2008), Yoram Wind argued that the discipline of marketing “hasn’t kept up” with the rapid changes of the 21st Century. He cited Tom Freidman’s concept of the flat world, the rise of China, the Internet, and social awareness as the markers of this observation.

What really happened is that the concept of commercial business as we knew it was undergoing a major disruptive set of changes. The concept of marketing had to adapt. In a 2014 Gartner report, called “Key Findings from U.S. Digital Marketing Spending,” James Rivera and Rob van der Mullen found marketing budgets in 315 companies were predicted to rise 8% and that 14% of the respondents planned to spend over 15% of their revenue on marketing budgets and salaries. Laura McLellan, vice president of research at Gartner says, “The line between digital and traditional marketing continues to blur. For marketers in 2014 it is less about digital marketing than marketing in a digital world.” This is a significant increase and bears further consideration.

How could this happen? There seems to be multiple contributing elements. They include:

- Breathtaking extension of the Internet into every walk of life.

- Mind-numbing extension of smart phones, tablets, and computer usage.

- The movement to a global competition for customer, resources, and markets.

- The rapid extension of social media such as Facebook and Twitter.

- Kindle, Nook, and MP3 in the publishing arenas.

- Success of Amazon and other e-commerce.

- Trained specialists in web design, viral marketing, and enabling technologies.

- New market search engines, such as Google.

Eric Von Hipple, the MIT professor of Innovation, wrote a text entitled Democratizing Innovation ,1 in which he observed that we are rapidly coming to the place where all of us can create our own commercial solutions. He used the example of how we can create concepts on our personal computers using AutoCAD or SolidWorks and then immediately transfer those ideas into parts through the use of rapid prototyping devices. These machines can be purchased on the open market for less than $1,000. Although the output of these devices is limited in scale, materials, and accuracy, it doesn’t take too much imagination to see where this might lead.

But how does all this connect to the commercialization of ideas? It is clear that as we discern how to increase the probability of success, these new channels and marketing tools must be brought into focus. Relying on older marketing tools is no longer sufficient.

The New Marketing Model

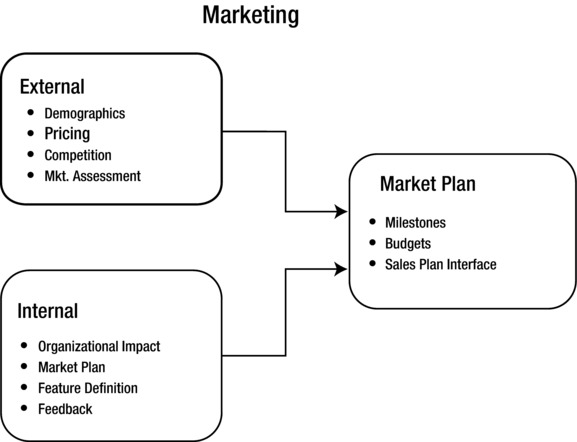

Within the context of a new model of the marketing paradigm created by the changes outlined previously, there is a need to look at commercial opportunities in a different context. A starting point is to look at the model from its organizational function, as shown in Figure 7-2.

Figure 7-2. Marketing function

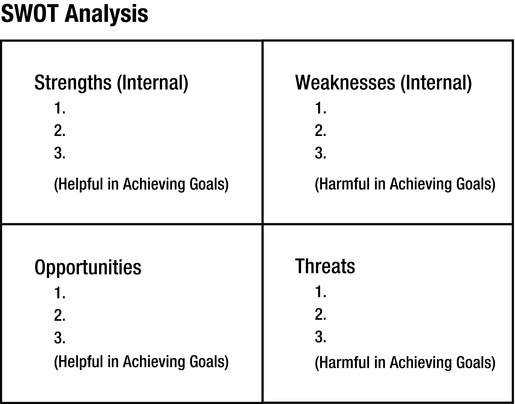

Of the many aspects of marketing that are of interest, two of them have particular focus. The first is a term similar to what pilots call situational awareness. It relates to a pilot’s ability to relate to the environment around her. It measures how well individuals respond to variable changes in that space. Markets rely on that ability. A tool that is employed is a matrix of the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT). It is graphically represented by models such as the one shown in Figure 7-3.

Figure 7-3. SWOT analysis format

The SWOT analysis is a mainstay of market assessments. In reading many business plans, I often find them presented but with static (one-time) information. In reality, a more accurate perspective would be a kaleidoscope of snapshots along a project’s journey to commercialization. Noting the dynamic changes (and how the project team reacted to them) becomes an important marker. It’s a sensitive indicator of the situational awareness confronting the projects. Tracking changes along the way becomes a powerful perspective about the project’s viability.

There is a potential that the marketing and sales groups operate in conflict. This derives from a lack of clarity about the two functions from upper management. It is the clear responsibility of upper management to define each function to offset these possible conflicts.

To clarify the potential issues between sales and marketing, it is useful to look at some of the critical components of each.

Demographics

In more traditional marketing models, demographics is the focus of what the first contribution the marketing function adds to the success. Demographics helps define:

- Who are the customers?

- Where do they live?

- What do they buy?

- How do they make purchases?

- What are they will to pay?

The list of defining attributes further includes age, gender, marital status, purchasing power, and so on. Included is the dynamic model of what changes or trends the project is undergoing. The information is creatively synthesized into a demographic model of a hypothetical aggregate customer. This information is then used as the basis of the marketing plan and formulation of a brand strategy. Like the SWOT analysis, this is not a one-time static vantage. It is a dynamic ever-changing landscape. The creative part is to utilizing this information by observing changes and trends and reacting to them.

Renee DiResta wrote an essay on O’Reilly’s RADAR entitled “Demographics Are Dead: The New Technical Face of Marketing.”2 In the article, she claims that marketing has been transformed from a primarily creative process to an increasingly data-driven discipline with strong technological underpinnings. Although marketing still has a primary mission of affording a connection to the customer, the pathways to the buying decision and the resulting buying patterns have seen a fundamental change. DiResta argues that the “Old Marketing used a ‘spray and pray’ model aimed at a relatively passive customer base.”

Advances in data mining have improved to the point where marketers can develop highly specific profiles of customers at the individual level using data drawn from actual costumer behaviors. Amazon is a good example. They maintain a living database of all transactions and inquiries made by the customers. When you log on to the system, Amazon suggests books and other products that are extensions of your personally indicated interests, as judged by your history of previous purchases.

Added to this new approach are the breathtaking deployments of laptops, tablets, and smart phones to consumers worldwide. They allow the consumers to become incredibly knowledgeable in product (and service) offerings as well as in pricing and supply chain availability. With this, traditional consumer loyalty has evaporated and a ferocious new competition occurs at the product/consumer interface. Coincident is the evolution of new marketing skills in data mining, web development, and “human-centric” applications awareness.

Pricing

In its fundamental terms, pricing is the process of determining what consideration a company will receive in exchange for its products or services. It is one of the four Ps of marketing. The others include Product, Promotion, and Place. The key influences on pricing include a bottom-up one driven by manufacturing and distribution costs, brand, product quality, and competition. The second consideration is one of “what the market will bear” and rewards the most efficient producer and distribution channels. The influence of off-shore manufacturing has influenced this equation significantly. Added to this is the presence of Walmart-type “big box” distribution and Internet-based Amazon-like services that allow products to be available to consumers in almost real time. The customer can certainly “vote with his or her feet” and influence the demographic profile in a ways that were simply not possible earlier.

Warren Buffett’s take on pricing is this, “Price is what you pay and value is what you get.”3 He further comments that “if you have the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve a very good business.”

To determine proper pricing requires a sound strategy that embraces the market and its competitive forces, as well as the corporate requirements for profits and returns on their investments. There are three dominant forces that help determine a strategic direction for pricing, discussed next.

This method is based on accounting data and focuses on a stated ROI corporate goal. It also embraces the concepts of breakeven (BE) and experience curve (EC) impact. Let’s look at both.

Breakeven accumulates the fixed and variable costs in manufacturing a product or service and projects future trends of each based on the units produced. It then overlays the revenue generated by sales and further defines the quantity (units) required to have the revenue line exceed the combined costs. Interestingly, the slope of the revenue line is based on the average selling price of the product. From that point, the process generates profits (and cash). Before that point, it absorbs loss. The relationship is expressed as follows:

![]()

Figure 7-4 shows this graphically.

Figure 7-4. Profitability and breakeven analysis

At a certain point, the fixed and variable costs per unit are matched by the revenue generated from the sale of the product (or services). From that point onward, the production yields a profit to be enjoyed by the organization.

The experience curve is based on an idea developed in the mid-1960s by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG). It developed the idea that the higher the volume of experience a firm has in producing a particular product (or service), the lower its costs should be. Bruce Henderson, the founder of BCG and the author of the text entitled “Management Ideas and Gurus” (Economist/ Profile Publishing, September 14, 2009), claims that with each cumulative doubling of experience, costs decline by 23–30%.4 In theory, this would imply a significant competitive advantage over time, as the company can control the pricing.

Time has altered the value of this model, as it does not incorporate the impact of innovation and change or off-shore competition. But as unit volume increases, automation and constant improvement can certainly sustain the value of experience.

In certain product areas, price becomes the dominant criteria for procurement decisions. Retail segments such as automobiles and airlines are examples. Significant attention is focused on sales (for example, President Day sales for automobiles), discounts, and bundled offerings (for example, “buy one get one free”). Although necessary, such marketing efforts tend to ignore demand cost functions and put corporate goals of profitably at risk. It also invites the creation of discount channels such as T.J.Maxx and Home Goods in the retail products market.

Competitive pricing is certainly one strategy to be considered. It has many alternatives, such as offering a family of products. General Motors manufactures (and sells) Chevrolet and Cadillac model cars. From a distance they are similar but can be sold at different price points to satisfy multiple markets. In reality, they are common in their ability to offer automotive transportation. Sometimes competitive pricing is used to move mature products in a way that extracts maximum value from declining profit margins.

Value–Based Pricing

Value-based pricing uses data based on the customer perception of value. A simple metric of cost-benefit analysis is used by many consumers.

A company located in the Boston suburbs called Phoenix Controls designed, sold, and manufactured a line of airflow controls used in harsh chemical environments. It worked on the principle of controlling regulated air flows in laboratories accurately and more linearly to demand. The basis for purchasing the equipment was manifold. It saved energy costs by precisely controlling the amount of flow needed in the workplace. It made the environment more energy efficient, quiet, and more temperature controlled. Each of these elements was factored into the proposal on a perceived cost- benefit basis as the buyer might perceive them. There were variations based on local conditions such as the local price of energy or labor. This method yielded a higher selling price than conventional cost-based models.

This value-based pricing has the highest impact on new or complex products where market or consumer procurement trends have not been identified. It also yields higher prices and gross margins. Those results help defer initial launch and development costs that are necessarily associated with new products. Because of this, it also invites competition earlier than a normal product cycle would.

One aspect of pricing that has changed remarkably is the influence of the Internet. An example is airline ticket pricing. Entrants like Travelocity and Expedia have entered the game and can produce a list of base flight costs between given cities for a large of array of airlines with the simple click of a button. The comparison is bit skewed by additional charges that can easily be added to the stated base number. Consumers have proven quite nimble in working around the limitations. This type of comparison can be done to almost any commodity that we all use. Pricing differences become invaluable and the strategic implications are enormous. Some of the tangible aspects include:

- Help the parent organization achieve its financial goals.

- Help position products (or service offerings) to attract customers.

- Help create a family of products (mix) to serve different customer requirements.

- Affects distribution channels that the products utilize to get to the customers.

- Can be used to infer product quality or level of utility.

- Can be used to support advertising and product discount strategies.

Pricing is possibly the most fluid parameter of the commercial cycle. It allows entry into a crowded market dominated by established players. It allows product (or service) offerings to be positioned in perceived value spaces in the market. It can significantly affect corporate profits. Given its importance, it is strange to see that pricing strategy is often far from the analytical or scientific disciplines. For anecdotal evidence of this, look at the Sunday flyer section of the newspapers. You’ll see seemingly endless sales and discounts designed to entice customers to the retail shops.

Pricing strategy can be categorized in the following ways. This not meant to be an inclusive list but rather a sample of the many directions available:

- Absorption pricing. A method of recovering fixed and variable costs.

- Contribution margin-based pricing. Where the factors driving gross margin contribution are used to determine the price. Responds best to high volume but is somewhat insensitive to market conditions.

- Skimming. With new products market share is sometimes compromised to yield early recovery of costs. This is risky in terms of branding and inviting competitors.

- Decoy pricing. Multiple offerings of similar products are offered at different prices.

- Freemium. Free or introductory offerings are made followed by a subscription. Used many times in the software market to entice new customers.

- Loss leader. A product (or service) is introduced at a lower price with the resulting sacrifice of profits. Its goal is to attract new customers early.

- Market-oriented pricing. This competitive strategy reaches for market share and is dependent on what others offer their products for. Although chasing the market might be positive, the risk to profitability is large and relies on good manufacturing and distribution controls.

- Value-based pricing. Used with some markets where actual material cost is a small part of the overall cost structure. A software CD is an example. Its value is in the content and requires constant understanding of the marketplace to implement.

Competition

The arenas of commercialization, pricing, and competition are intertwined. In the literature surrounding technology commercialization, the role of competition in the evolution of a commercial product is complete with supporters and detractors. Even the early economic commentators had their say. Karl Marx, in his classic tome entitled Capital,5 wrote that competition “impeded the free movement of capital” and allowed the “disruption of capital that had already been invested.” Considering his criticism of capitalism, this might have been a valid perspective.

Adam Smith, the economist and a social commentator, in his much-touted Wealth of Nations,6 spoke of the competing forces of self-interest and competition, while not acting with the intent of serving others, acted as an “invisible hand” that eventually served the benefit of mankind.

Joseph Schumpeter—a 20th Century economic and political thinker—takes a more positive view and argues that competition is not an efficient economic driver but does acknowledge that entrepreneurial innovation serves as an engine for growth. He points out that investment in R&D correlates to productive growth. Innovation, he argues, leads to “creative destruction” of old inventories, ideas, technologies, and skills. He outlines these theories in the classic book entitled Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy.7

Whatever import you place on competitive forces, it is clear that going forward, you need an applied strategy to learn from them and to deal with them.

Competition and Commercialization

A modern context for competition allows for disruptive forces to be acknowledged and mitigated. The forces become a relevant fact of life and must be accommodated in the business or project plan. From a societal point of view there are three vital functions that competition serves. They include:

- Discovery. The discovery of new knowledge is an inherent attribute of human nature. Instilling this into the commercialization process yields a distinct advantage. It is well within the realm of self-interest. Sometimes it can be motivated by societal initiatives, such as the technological improvement that resulted from our quest for a clean environment. An example is the use of catalytic mufflers in automotive applications. The catalysis of exhaust gas had been known in the laboratory but it wasn’t until the government standards for emissions were implemented that automotive muffler applications became standard.

- Selection and coordination. The actual procurement decision that transfers financial consideration for goods or services is a powerful form of “voting” for orderly innovative commercialization. Innovation ranges from ideas to breakthrough changes. It is the decision to buy that innovation that sets up an orderly progression of ideas.

- Control of power. The power to create wealth from innovation is controlled by how well the market presents and delivers the ideas to those that will eventually use them. It acts a force to distribute wealth. External control such as government regulations and societal rules also prevail. Antitrust is an example of such an artificial check and balance. Although those laws restrict the movement of ideas, they also even the potential abusive use of those forces toward commercial realty.

Competitors

Quantifying a project’s competitive forces comprises several steps. They include:

- Identifying who the competitors are. They can be a totally new business, a new product, or even a new technology. They can be identified well before business opportunities are lost. Simple observations like their advertising, presence at trade shows, Internet sightings, patent searches, and simple dialogue with existing customers.

- Identifying them is not enough. Knowing what products they offer, how they distribute them, their annual reports (if public) or their SEC filings, their pricing schedules, who they identify as customers, and possible their financial resources. Checking their literature is a great starting point.

- Dealing with them. Competitors offer an opportunity to learn and innovate. Observing how they go to market is a chance to improve that process. Sometimes the best strategy is to build on your own strength. Improving your customer service response function is an example. Continuous internal improvement is solid way to improve customer effectiveness and competiveness.

The Impact of Competition on Marketing

As economists debate the intersection of competition and innovation, it becomes important to focus on the impact of this debate on the marketing of new products and services in the commercialization cycle. Sometimes it is positively disruptive. Examples such as 3M’s Post-it Notes and Toyota’s Prius created new market segments. Other times, this power of innovation is disruptive in a negative sense.

In Clayton Christensen’s text titled The Innovator’s Dilemma,8 he explains how innovative changes in the size, form factor, and performance of disk drives occurred so quickly that the current offerings were obsolete before they had a chance to exploit their full product lifecycles. Subsequently, there was a fallout of disk drive producers from 35 to 14 companies in the industry. Innovative changes also tend to provide downward pressure on pricing.

Competitive forces exist in any viable commercial opportunity. Something will be challenged or face change when an innovative product or service is introduced. Whether perceived as a positive or negative force, they are an inevitable fact of life. It seems analogous to strategic selling (cited earlier in the book; see Chapter 5), where many influences surround the actual purchasing decision process. The influences could be financial (and cost), technology, market-driven items such as branding, quality, or exposition of features and benefits. Like the strategic selling analogy, any one (or combination of) force can compromise a project’s effectiveness, and have the power to negate a sale.

It is the CEO who must correctly identify the competitive risks, then act to offer mitigation alternatives to overcome them. Once identified, there are usually multiple options to neutralize the threats. In product design, for example, there are families of product design that can be populated to allow multiple technical personalities from a common platform. Anticipating them and providing options is where the successful projects thrive. In the marketing area, there are multiple branding, distribution, and pricing strategies for any one product or service offering. Within the marketing space there are still fundamental tools such as SWOT analyses, five-point strategy tools, and many more that help outline available alternatives.

Going to Market

One more time in our search for improved paths to commercialization the need for succinct planning arises. This time the issues are quite tactical. It starts with a situational analysis that describes the customer behavior and the market environment as it currently exists. It outlines the outside forces that can impact the success of the project. These include anything from competitive elements to regulatory ones. Clearly, they define a target customer audience and describe their purchasing patterns (and quirks). Most important they offer a strategy or approach as to how to overcome them.

New products and services have the potential to disrupt and alter the brand and image of the parent company. Most times this direction is positive but its impact needs to be studied. The nature of the marketing disciplines certainly differ with a company’s existence and the lifecycle of its operations. The planning disciplines are certainly more prevalent and formal as the organization matures. Finally, the budgets that control cost and the resulting impact on upside revenues need to be delineated.

Why bother to embrace the effort to create this plan? The answer lies in the fact that most new projects seem to stumble in market domain. The risk is that the company expends resources but does not benefit from the revenues and resulting profits it hopes to achieve. This can be avoided.

Why Marketing: A Summary

Of all functional disciplines, marketing probably has the most significant impact on the success of the outcome. The results of a successful marketing and sales campaign translate directly into financial performance and overall project satisfaction. Technological components, human resources, operational issues, and even financial support can usually be corrected. Marketing issues and their resolution are the litmus tests for the customer and their quirks. These issues can’t be solved in real time and thus must be thought through and planned.

All issues surrounding new products and services destined to commercialization must face the scrutiny of being quantified. It is the only hope of rationalizing those elements that they can be reduced to analysis. It turns out that there are many parts that can be quantified. Let’s look at some of the most important elements in the next chapter.

________________

1MIT Press. Creative Commons License, 2005.

2radar.oreilly.com/2013/09/demographics-are-dead-the-new-technical-face-of-marketing.html.

3Management Ideas and Gurus (Economist/Profile Publishing, 2008).

4University of Bergano Press, third edition, 1999.

5Oxford University Press, 1776.

6Harvard University Press, 1934.

7New York: Harper Collins, 2003.