Big Brother and Global Competition

Invasive for sure, the government’s impact on commercialization is enormous. A long alphabet soup of interventions such as OSHA, EPA, FDA, IRS, SEC, PTO, UCC, CE, UL, Sarbanes-Oxley, tariffs, and other applicable laws and regulations affect all technological projects. Issues of control, reporting, and constraints hobble the very best commercial opportunities. Tomes have been written about the massive political and economic shifts taking place at a global level—in material resources, capital, human talent, manufacturing bases, government support, and more. While no one really understands the impact of the shift of manufacturing and services to Asia, for example, it’s clear that there are new metrics for success. This chapter shows how people and companies compete in a world racing into the future.

We live in a time of unprecedented government and legal involvement in the way we start and operate modern enterprises. If this weren’t complicated enough, in the United States, global pressures and competitive forces have increased the complexity of external involvement exponentially. Some argue it is better and some argue the other way. Whichever way the judgment call falls, we can agree that these trends can’t be ignored. The government (both local and federal) significantly impacts the operations and responsibilities of a modern project or company. Their combined influence severely impacts its potential financial performance.

The application of various laws and regulations is not comparable in other countries. This leaves projects developed in a strong regulatory environment less able to compete. Compare manufacturing in the United States and China and you see China’s imminent advantage of minimum environmental constraints, low wages, and nonexistent commercial rules that are so imbalanced that competitive manufacturing by U.S. entities is severely handicapped. This chapter examines those influences. By the end we will deduce whether they are good or not for improving the odds of commercial reality. In either case, we will see how they are integrated (intertwined?) into the total commercialization models.

A Perspective

A strange observation about governmental regulation processes is that governments and businesses have common goals of promoting prosperity and growth while protecting our environment and wellbeing. Yet, at the operating level the programs and regulations have become vehicles for creating working tensions between management and bureaucracy. To gain a perspective on this uneasy alliance, it is best to look back in history.

In 1835, Alexis de Tocqueville, the French Aristocrat, toured the United States. The authors, Jeffery Beatty and Susan Samuelson, in their defining text entitled Business Law and the Legal Environment, quoted him as observing “scarcely any political question that arises in the United States that is not resolved, sooner or later gets resolved in the courts.” We seem hooked on resolving large issues in the legal framework. Whimsically, our country was formed to protect us from our parent governments in England. Religious freedom and taxes (dumping tea in the Boston Harbor) are examples.

Our legal framework had its roots in the English Common Law system and even in our language. An example is the word sheriff. It is derived from the role of individuals called “shire reeves” (Beatty and Samuelson). Shires were the local English countryside communities and the shire reeves were the voice of the legal system. They collected taxes, mediated disputes, and even apprehended criminals. There was only a vague reporting to the central court system for their work.

When the French Normans invaded England in 1066, they instilled more discipline in real estate transactions 1) as a means of legitimizing land distribution by the Normans and 2) setting the precedent as a basis for common law. The earliest transactions were recorded as early as 1230.

Although the roots of the legal system were bound in history, the proliferation of laws and regulations as we know them today had a boost in the growth of our economy. The U.S. Constitution was written in 1787. It declared the right of the government to regulate commerce and provide for the safety and wellbeing to the country. A major example was seen in the legislation that arose from the early sweatshops that enabled the unions to seek organization and lobby for their membership. The legislation further grew when the Industrial Revolution occurred in the 19th Century. Similar boosts were seen in the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administrations of the 1940s as he drove for new agency development into economic crises the country faced following World War II.

Today we question whether the pendulum of government involvement has swung too far. Roger Trapp in an article published in Forbes entitled “Is It Time for Business and Government to Reconsider Relationship,”1 argues that a new construct for how government and business act must be developed. Relying on government alone is not the answer. This theme is further developed in a book authored by William Eggers and Paul Macmillan entitled the Solution Revolution.2 They cite examples like crowdfunding, ride-sharing, malaria in Africa, and traffic congestion in California. Trade solutions instead of just money grants may indeed fuel the solution revolution. Further, the report 15% annual growth of new ventures and even Fortune 500 companies in such a space. It is a hopeful scenario.

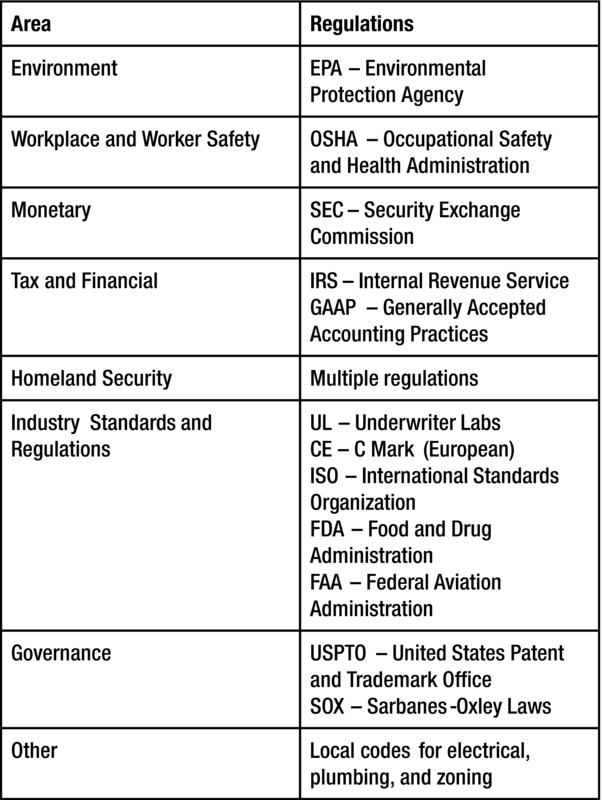

Specifically, we question whether the overall implication of the government intrusion in the business model has created a construct that compromises the probability of success of new projects and ventures. If enterprises around the world do not have these relationships, the balance is uneven and makes it harder to compete. A partial list of these relationships is shown in Figure 11-1.

Figure 11-1. Government and business

It becomes tempting to look at the history of this involvement and trace its connections to modern enterprise. Certainly most of the rules were motivated by intentions of social good, environmental concerns, worker safety, and wellbeing. Even for those that are less altruistic in intent, one must ponder what the sum of the involvement does to the ability of a given project or firm to compete locally and globally.

I’m reminded of a story in my company that might serve as an example of this. Our projects were typically large in scope. The details were captured in project books consisting of three ring binders typically four inches wide. One project was in the United Kingdom. It was at a new Glaxo Pharmaceutical company lab in Stevenege, England. It took three years to secure the project. The project book for that effort was comprised of three such binders. No other project book in the company could match its details and complexity of regulations. The UK seemed determined to add layers of complexity.

It would be tempting to extrapolate this and suggest that the UK is handicapped in its ability to innovate and develop new products. Hardly the case, but one must wonder what impact the myriad of regulations has on the equations that control the probability of success of these ventures. The UK is years ahead of the United States and most other Western countries in their maturity of government interaction and regulation. The project books were just a visual representation. Is this detail any better and more relevant to this text? More important, how does it impact the probability of success of new and innovative projects?

Within the UK the environment is hardly static. Evidence of pendulum-like thinking was realized with the passage of legislation that enabled the creation of a Department for Business, Innovation, and Skills (BIS) in June, 2009. BIS allowed the merger of the Department for Innovation, Universities, and Skill (DIUS) and the Department for Business, Enterprise, and Regulatory Reform (BERR). The combined agencies embraced business regulation, company law, consumer affairs, employment relations, export licensing, higher education, and innovation. Changes are rationalized on increased efficiency and productivity. Political motivations are diminished. In the UK and other governments in the world, these changes are referred to as modifications in the Machinery of Government (MoGs).

As the forces of government interaction shift around the world, opportunities to innovate and successfully implement change move. China has long been a source of low-wage manufacturing. As their population and economy shifts to the cities, environmental and regulatory issues now appear as part of the landscape. Lower-cost manufacturing is shifting to other places in the Far East. The Chinese economy now boasts the manufacturing of airplanes and ships as part to its capacity.

To focus on any one global force may not be as important as recognizing the need for modern companies and projects to be “nimble” and “adaptive.” These may be the next set of critical metrics of successful entities. What is intriguing is how early in the lifecycle these issues appear. Historically, they used to be issues of mature and later-stage entities. The timeline for adapting global alliances is long compared to the shortening lifecycles of new technological opportunities.

Global influences are tied directly to governmental interventions. There may be both positive and negative examples. There may be tax incentives, priority transfer options, and even direct subsidies for certain product and service areas. Equally, there may be restrictions and regulations that impact a given market sector. This is particularly true for technology-based products. An example of this comes from the automotive industries. For many areas certain safety specifications for items like the headlights, windshields, and bumpers were strictly applied to cars shipped to America. Most European and Far Eastern-produced cars could not meet these and relied on aftermarket organizations to provide them. The additional costs could result in the products being noncompetitive. There are stories of individuals visiting Stuttgart, Germany to pick up their Mercedes Benz cars only to be allowed to drive them in Europe (for tariff considerations) and then returning them to the plant for the cars to be remanufactured to the U.S. standards for an additional fee—amazing!

The Global Competition

Twenty-five years after the Russian Sputnik was launched, the United States convened a prestigious committee of academics and industry leaders under the stewardship of John Young, president of Hewlett-Packard. Its mission was to assess the state of America’s ability to compete in the arena of global competition. The report was entitled “Global Competition, The New Reality.” The date of publication was January 1985.

Briefly, the report concluded that America’s “ability to compete in world markets must be improved.” To “strengthen our competitive performance,” we must:

- “Create, apply, and protect technology-innovation that spurs new industries and revives mature ones.

- Reduce the cost of capital to American industry and increase the supply of capital for investment.

- Develop a more skilled, flexible, and motivated work force.

- Make trade (exports) a national priority.”

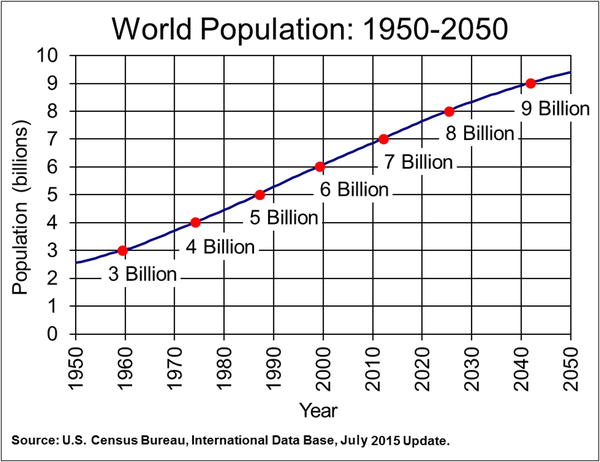

The report goes on to argue for incentives to create more public/private collaborations and to seek new models of commercialization. What is so amazing is that today’s literature argues for these same directions. It then becomes important to recognize what has changed since that report. The rate of change of communication (via the Internet) and the advances in enabling technologies that have been noted in this book have increased at breathtaking speeds. The global population has increased from 4.5 to 7 billion (see Figure 11-2), natural resources have dwindled, and the balance of trade has shifted from Europe and the United States to the Far East. All of these factors impact the probability of success in the projects and the new enterprises we might contemplate.

Figure 11-2. World population 1950–2050

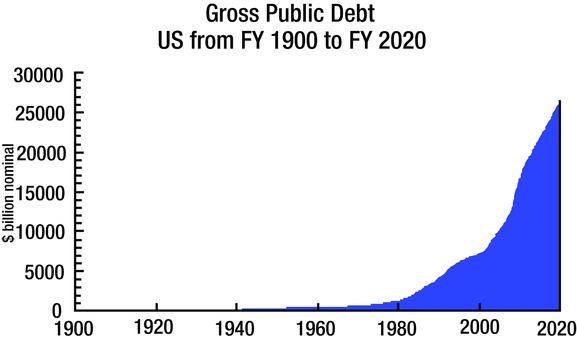

Perhaps the most troubling part of this dialogue is that the ability of the United States to fund new innovations and embark on new trade initiatives has diminished remarkably. At the time of the commission’s report (1985), the gross public debt was a nominal $2.5 billon; today it approaches $15 billion. Servicing the debt alone becomes monumental and compromises the ability to fund new directions (see Figure 11-3).

Figure 11-3. U.S gross public debt3

Each year, the Battelle organization and R&D Magazine publish a Global R&D Funding Forecast. In the 2014 edition, they reported that U.S. R&D funding rose by 1%. In the same time period, China’s increased spending by 6.3% and Europe by 4.6%. In combination, these three areas spent 87% of the world’s R&D for a level of $1.6 trillion. If the year-to-year trends continue, the Asian countries, including China, will outspend the United States by 2018. Within the U.S. category, 70% of the R&D spending comes from industry.

In the narrative of the report, it states that “R&D is a long-term investment in the future that serves as the cornerstone for innovation-driven growth.” It then elaborates about the importance of an ecosystem to utilize the benefits of R&D. The ecosystems allows the benefit to “stick” until commercially viable. Elements of the ecosystems include:

- Large investments in human capital to ensure a talent pipeline of the required skills. The importance of STEM programs was emphasized.

- Science is partnered with commercial visions and entrepreneurial efforts to allow advancements of the efforts.

- Capital is available for all stages of effort from R&D through proof-of-concept to the final product.

- Government support is established and responsive to industry collaborations with academia.

When the report investigators asked leading researchers about the concern in affecting future trends, there was a surprising finding in that global trends such as natural disasters and renewable energy sources were high on the list.

To extend the issue further, measures of productivity reveal the potential for global growth. In a report from the McKinsey Global Institute entitled “Global Growth: Can Productivity Save the Day in an Aging World?”,4 it was indicted that we have enjoyed a period of 50 years of growth as measured in GDP. The rate of growth changed from 2.8% per capita growth to 2.4%. Although this change seems small, it is further complicated by the number of emerging countries that help to drag down the overall performance. Nigeria, for example, would have to boost their productivity by 80% to catch up to the global numbers. The report focuses on agriculture, food processing, automotive, retail, and healthcare. It was relatively optimistic that we have not run out technology and innovation that could be utilized to improve our global productivity but question whether we have the governmental and industrial will to adapt to the best practices we will need.

At a macro level, trends appear that are buffeted by local economies, currency, and political changes and the dynamics of emerging economies. Through the openness of the Internet and global transport capacity, the forces impinge on new opportunities and can diminish the probability of their success. On the other side, global shifts can also present opportunities in terms of collaboration and business exchange.

An example of this was conveyed to me by a former executive of the Dennison Corporation of Framingham, MA. The company was involved in the manufacture of pricing tags for the retail industry. In the clothing goods sector, they observed that particularly high-end products were often designed in Paris or Milan, manufactured in the Far East, and finally sold in American distribution channels. Cataloging and displaying consumer tag information accurately and in a timely manner became daunting because of the many hands and disparate locations that the products and services utilized in the goods manufacture of the products. They developed a process where the stages of tag information could be generated in real time in the disparate locations. The overall productivity (and error losses) were quite positively impacted. Of course, there are many other examples of this type of global interaction. What is so intriguing is that they would have been unavailable just a few years ago, before the technologies used to accomplish them were available.

In Figure 11-1, we started to look at how regulatory constraints and compliance requirement can impact even the earliest of commercial projects. It is appropriate to look at some of these details more closely. A starting point might be just to look at the list of agencies and rules that impact any organization, including the startups. The agencies are broadly categorized as Federal and Local (state and municipality).

Perhaps an entry point into the world of governmental involvement might be the Small Business Administration (SBA). Started in 1953 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, it had two sweeping mandates. The first was to administer multiple levels of government-backed loans to small business for both the capital and growth projects. The second direction was to “aid, assist, counsel, and protect, insofar as possible, the interests of small business concerns.”5 It went through many iterations and was buffeted by both Republican and Democratic forces. The Democrats wanted to enlarge its scope, while the various Republican administrations went as far as trying to abolish it. Today, under the Obama administration, there is movement to bring the SBA to presidential cabinet visibility. In addition, in December 2010, President Obama created the Small Business Jobs Act to not only allow an additional $30 billon in lending programs but also to provide up to $12 billion in new tax cuts for smaller enterprises.

SBA is huge. It is comprised of 22 separate offices with interest ranging from entrepreneurial education to international trade to veterans’ business and women’s business ownership. Within its broad reach, it also helps administer SCORE, which is the Service Corp of Retired Executives. SCORE is a mentor group comprised of 350 chapters around the country. The SBA has at least one office in each state, approximately 900 Small Business Development Centers located in colleges and universities, and 110 Women’s Business Centers to assist in its outreach into the early stage community. Some of the specific outreach initiatives it sponsors include (not in order):

- Intellectual property. The issues surrounding patents, copyright, and the myriad of issues surrounding “the freedom to operate” in a litigious society.

- Environmental regulations. Deals with multiple regulations involved with not only working with material for manufacture but rules dealing with the full cycle of all materials.

- Foreign workers. The laws dealing with employment eligibility and the ever-changing immigration rule as the political winds surrounding them change. Included are the issues surrounding the search for the best international talent, which is rigidly controlled by Visa regulations.

- Employment and labor. The specific rules that surround the hiring of general workers.

- Business law. From the basic of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) that regulates contracts and business transactions to specifics such as those that regulate commerce on the Internet.

- Financial laws. Accounting transactions are subject to multiple laws, starting with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) for public equity transactions to full accounting transaction practices under the Generally Accepted Accounting Practices (GAAP).

- Regulations and permits. There are multiple codes and permits for operations that appear on the local level that embrace plumbing, electricity, and other municipal services.

Even if these interfaces are proper and help regulate the flow of commerce, each interaction, whether small or large, costs time and human resources. If projects are to realize their potential, the additional burdens must be borne by the enterprise. At minimum, a certain level of marginal or more fragile projects are declined. What would have happened if certain ideas, ranging from the cotton gin to the automobile to the television and the phone, had been subjected to the levels of scrutiny now employed? Some of these technological innovations helped define America in global markets.

If this is extended to a global perspective, the rules are not designed for parity. Certainly the environmental concerns and regulations in China are trivial compared to the United States and Europe and are grossly imbalanced. To offset this, there are multiple governmental and political initiatives that seek parity among the countries. Global carbon tax efforts that normalize global shifts in the environment are an example. Agreements such as these are certainly subject to political pressures. One example is the Kyoto protocols, which were essentially boycotted by the United States. Without America’s participation, the impact of these environment laws was nullified. Until the agreements are secured, each element of government intervention establishes commercial imbalance. These imbalances are registered directly on the potential profitability and capital requirements of doing business in each sector. One has to wonder how much consideration is given to the various trade imbalances that are created when these laws and regulations are crafted.

There are offsets and new opportunities created in this implosion of regulations and laws. One might be seen in the case where the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) promulgates new emission standards for heating plants. Older technologies such as coal-fired open stack heaters are being replaced with more efficient and cleaner technologies such as natural gas and exhaust stack scrubbers. Clearly these are better for the environment and maybe even more efficient in the delivery of heat to a given facility, and the conversion deflects the use of capital that might have been used to create new enterprises. That new commercial opportunities for natural gas heaters and scrubbers might be rationalized as the benefit. Even if this is so, the overall productivity is compromised.

Drilling Down

Governmental and regulatory influences on early stage projects seems to fall into three categories. They include environmental concerns, worker rights and safety, and regulation of commerce. Each category has its roots in promoting social or environmental concerns and certainly can be justified in this basis. Specific areas of the world such as Europe and Scandinavia are known for the presence of strong and invasive interactions. The Far East and China in particular are at the other side of the balance argument and currently have less stringent rules. Each of these areas is undergoing constant change. It is a moving target. There is a long list of global trade and environmental commissions and treaties seeking to normalize them. Clearly it is a fluid set of balances and interactions.

If the new world of opportunities ahead embraces a global competitions, the range of interactions is large and at any one time seems to be imbalanced. Given that, early stage projects seem increasingly vulnerable to a set of constraints that are well beyond their capacity to meet. Let’s look at the specifics of a startup manufacturing entity in the three dimensions of environmental regulation, worker rights, and safety and commerce regulation.

In each category, there is at least one dominant regulatory agency. In the American environmental space, for example, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is the dominant force. Created by executive order under President Richard Nixon in 1970 and later ratified by the House and Senate, it has broad regulatory and enforcement powers in the space of air and water quality. Its scope embraces the air, water, land, and endangered species and hazardous waste regimes. It has spawned endless regulations and governing laws that impact both small and larger entities.

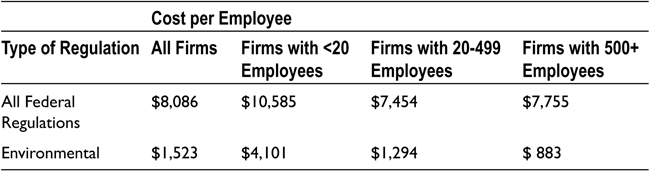

In a report entitled “The Impact of Regulatory Costs on Small Firms” by Nicole and W. Mark Crain6 a significantly larger share of compliance of the environmental regulations was borne by smaller companies. This is shown in Table 11-1, published in the report.

Table 11-1. Distribution of Environmental Compliance Costs by Firm Size in 2008

What seems so astonishing is how skewed these costs are with respect to the size of the companies. Those earlier stage organizations that we rely on to be innovative and become the basis for successful commercialization of technology are hit hardest. As Table 11-1 further suggests, this disproportionate burden is also borne by smaller companies in all governmental regulatory categories.

To look at anther slice of this disproportionate balance, we can look at an accumulation of economic forces such tariffs, fees, and taxes to see similar patterns in the category of all Federal regulations. Although beyond the scope of this report, there is another layer of local and state costs such as taxes and permit fees that must be added to the tally. Many of the costs are “fixed” expenses that must be borne independent of the number of employees. These costs tend to hide in the accounting models and are not listed as line items.

There is clearly a balance between public and private allocation of funds. If a corporation invests in a given environmental technology to improve its productivity technology, that is one category that may give it commercial advantage. If the investment is made to satisfy an EPA regulation, that is another. That decision is more that an accounting convenience, but rather is a major force that affects the company’s competitive position.

Not only does this burden fall on companies least capable of accepting the financial and cash flow burden, but it sets up an imbalance in the competitive global and foreign markets. Technology and innovative solutions alone cannot provide the balance needed for any one country to compete. The basis for many regulatory elements may indeed have altruistic and sustainable arguments. They certainly a based in political forces. Somehow there must be equilibrium of forces to compensate for these imbalances. If China or a third-world country can dump products into the U.S. economy that have minimal environmental effects, it does seem to be unfair economic element.

Putting It Together

In this chapter, we looked at the many ways the various federal, state, and local governmental organizations impinge on the modern corporation. The rate of involvement is unprecedented. Although the basis of many regulations seems altruistic, their purpose and scope are disproportionate in the way they impact smaller entities. This puts a burden on the early fundraising efforts and the resultant dilution of equity, and it also limits the use of capital that can be applied to the organization’s growth purposes. What is more compelling is how powerful the environmental and economic constraints are around the world. In addition, they also change. Combined with the disproportionate regulatory burden on the early stage company, one wonders what the ability of any one country to innovate and recognize the benefits of commercial activity will be going forward.

To be sure, not all regulations bring with them financial and human resource obligations. Some are actually additive in nature. Examples include reduction of certain tariffs or Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants that allow collaboration between academia and industry partners. There might be local and federal incentives to provide solar energy. There might be available job training or job creation incentives. These programs prevail in all aspects of an ongoing enterprise. Cleary those incentives must be incorporated into operating plans and utilized when possible. If they provide a global competitive edge, then they must be employed. Whether the incentives are driven by social, political, or altruistic motivations, they are in a state of constant change. The management of the new technological-based enterprise requires a level of nimbleness and adaptation that has never been required before to take advantage of them.

Looking Ahead

With the rapidly changing landscape of elements in the commercialization of technology, it becomes uncertain to forecast what parts will have the most significant impact. In the next chapter, however, we will look at new trends of investments and opportunities. In addition, we will look at the changing roles of incubation, patent law, market communication, and the Internet. We will also look at how teams are formed. In addition, we will examine these changes in a global context. For sure, it will be an exciting time ahead.

_____________________

1August 31, 2014.

2Harvard Business Press, September 2013.

3Source: www.usgovernmentspending.com.

4McKinsey and Company, 2015.

6Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy, September, 2010.