Chapter 4. Objects and Classes

In this chapter

• 4.1 Introduction to Object-Oriented Programming

• 4.2 Using Predefined Classes

• 4.3 Defining Your Own Classes

• 4.4 Static Fields and Methods

In this chapter, we

• Introduce you to object-oriented programming;

• Show you how you can create objects that belong to classes from the standard Java library; and

• Show you how to write your own classes.

If you do not have a background in object-oriented programming, you will want to read this chapter carefully. Object-oriented programming requires a different way of thinking than procedural languages. The transition is not always easy, but you do need some familiarity with object concepts to go further with Java.

For experienced C++ programmers, this chapter, like the previous chapter, presents familiar information; however, there are enough differences between the two languages that you should read the later sections of this chapter carefully. You’ll find the C++ notes helpful for making the transition.

4.1 Introduction to Object-Oriented Programming

Object-oriented programming, or OOP for short, is the dominant programming paradigm these days, having replaced the “structured” or procedural programming techniques that were developed in the 1970s. Since Java is object oriented, you have to be familiar with OOP to become productive with Java.

An object-oriented program is made of objects. Each object has a specific functionality, exposed to its users, and a hidden implementation. Many objects in your programs will be taken “off-the-shelf” from a library; others will be custom designed. Whether you build an object or buy it might depend on your budget or on time. But, basically, as long as an object satisfies your specifications, you don’t care how the functionality is implemented.

Traditional structured programming consists of designing a set of procedures (or algorithms) to solve a problem. Once the procedures are determined, the traditional next step was to find appropriate ways to store the data. This is why the designer of the Pascal language, Niklaus Wirth, called his famous book on programming Algorithms + Data Structures = Programs (Prentice Hall, 1975). Notice that in Wirth’s title, algorithms come first, and data structures come second. This reflects the way programmers worked at that time. First, they decided on the procedures for manipulating the data; then, they decided what structure to impose on the data to make the manipulations easier. OOP reverses the order: puts the data first, then looks at the algorithms to operate on the data.

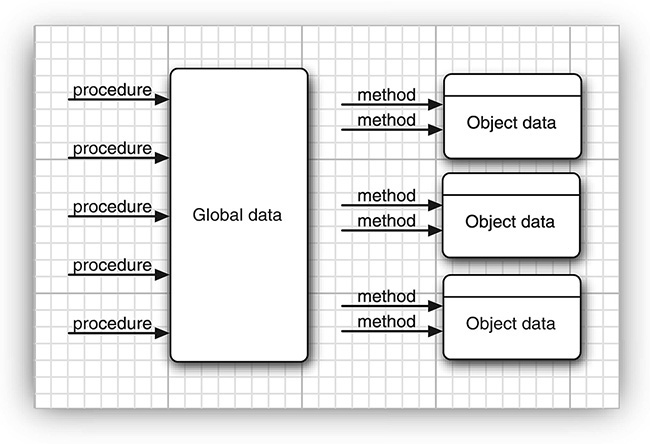

For small problems, the breakdown into procedures works very well. But objects are more appropriate for larger problems. Consider a simple web browser. It might require 2,000 procedures for its implementation, all of which manipulate a set of global data. In the object-oriented style, there might be 100 classes with an average of 20 methods per class (see Figure 4.1). This structure is much easier for a programmer to grasp. It is also much easier to find bugs in. Suppose the data of a particular object is in an incorrect state. It is far easier to search for the culprit among the 20 methods that had access to that data item than among 2,000 procedures.

4.1.1 Classes

A class is the template or blueprint from which objects are made. Think about classes as cookie cutters. Objects are the cookies themselves. When you construct an object from a class, you are said to have created an instance of the class.

As you have seen, all code that you write in Java is inside a class. The standard Java library supplies several thousand classes for such diverse purposes as user interface design, dates and calendars, and network programming. Nonetheless, in Java you still have to create your own classes to describe the objects of your application’s problem domain.

Encapsulation (sometimes called information hiding) is a key concept in working with objects. Formally, encapsulation is simply combining data and behavior in one package and hiding the implementation details from the users of the object. The bits of data in an object are called its instance fields, and the procedures that operate on the data are called its methods. A specific object that is an instance of a class will have specific values of its instance fields. The set of those values is the current state of the object. Whenever you invoke a method on an object, its state may change.

The key to making encapsulation work is to have methods never directly access instance fields in a class other than their own. Programs should interact with object data only through the object’s methods. Encapsulation is the way to give an object its “black box” behavior, which is the key to reuse and reliability. This means a class may totally change how it stores its data, but as long as it continues to use the same methods to manipulate the data, no other object will know or care.

When you start writing your own classes in Java, another tenet of OOP will make this easier: Classes can be built by extending other classes. Java, in fact, comes with a “cosmic superclass” called Object. All other classes extend this class. You will learn more about the Object class in the next chapter.

When you extend an existing class, the new class has all the properties and methods of the class that you extend. You then supply new methods and data fields that apply to your new class only. The concept of extending a class to obtain another class is called inheritance. See the next chapter for details on inheritance.

4.1.2 Objects

To work with OOP, you should be able to identify three key characteristics of objects:

• The object’s behavior—what can you do with this object, or what methods can you apply to it?

• The object’s state—how does the object react when you invoke those methods?

• The object’s identity—how is the object distinguished from others that may have the same behavior and state?

All objects that are instances of the same class share a family resemblance by supporting the same behavior. The behavior of an object is defined by the methods that you can call.

Next, each object stores information about what it currently looks like. This is the object’s state. An object’s state may change over time, but not spontaneously. A change in the state of an object must be a consequence of method calls. (If an object’s state changed without a method call on that object, someone broke encapsulation.)

However, the state of an object does not completely describe it, because each object has a distinct identity. For example, in an order processing system, two orders are distinct even if they request identical items. Notice that the individual objects that are instances of a class always differ in their identity and usually differ in their state.

These key characteristics can influence each other. For example, the state of an object can influence its behavior. (If an order is “shipped” or “paid,” it may reject a method call that asks it to add or remove items. Conversely, if an order is “empty”—that is, no items have yet been ordered—it should not allow itself to be shipped.)

4.1.3 Identifying Classes

In a traditional procedural program, you start the process at the top, with the main function. When designing an object-oriented system, there is no “top,” and newcomers to OOP often wonder where to begin. The answer is: Identify your classes and then add methods to each class.

A simple rule of thumb in identifying classes is to look for nouns in the problem analysis. Methods, on the other hand, correspond to verbs.

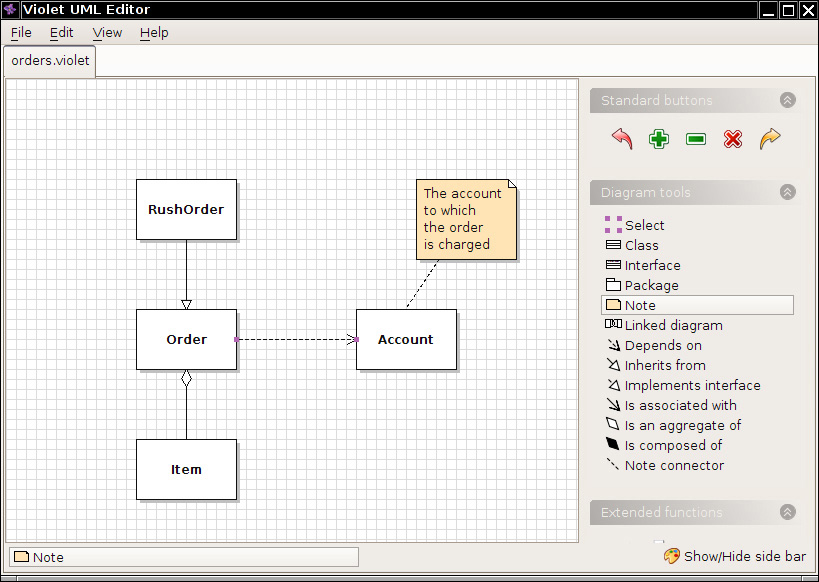

For example, in an order-processing system, some of the nouns are

• Item

• Order

• Shipping address

• Payment

• Account

These nouns may lead to the classes Item, Order, and so on.

Next, look for verbs. Items are added to orders. Orders are shipped or canceled. Payments are applied to orders. With each verb, such as “add,” “ship,” “cancel,” or “apply,” you identify the object that has the major responsibility for carrying it out. For example, when a new item is added to an order, the order object should be the one in charge because it knows how it stores and sorts items. That is, add should be a method of the Order class that takes an Item object as a parameter.

Of course, the “noun and verb” is but a rule of thumb; only experience can help you decide which nouns and verbs are the important ones when building your classes.

4.1.4 Relationships between Classes

The most common relationships between classes are

• Dependence (“uses–a”)

• Aggregation (“has–a”)

• Inheritance (“is–a”)

The dependence, or “uses–a” relationship, is the most obvious and also the most general. For example, the Order class uses the Account class because Order objects need to access Account objects to check for credit status. But the Item class does not depend on the Account class, because Item objects never need to worry about customer accounts. Thus, a class depends on another class if its methods use or manipulate objects of that class.

Try to minimize the number of classes that depend on each other. The point is, if a class A is unaware of the existence of a class B, it is also unconcerned about any changes to B. (And this means that changes to B do not introduce bugs into A.) In software engineering terminology, you want to minimize the coupling between classes.

The aggregation, or “has–a” relationship, is easy to understand because it is concrete; for example, an Order object contains Item objects. Containment means that objects of class A contain objects of class B.

![]() Note

Note

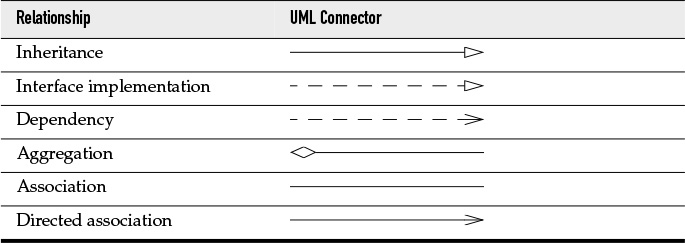

Some methodologists view the concept of aggregation with disdain and prefer to use a more general “association” relationship. From the point of view of modeling, that is understandable. But for programmers, the “has–a” relationship makes a lot of sense. We like to use aggregation for another reason as well: The standard notation for associations is less clear. See Table 4.1.

The inheritance, or “is–a” relationship, expresses a relationship between a more special and a more general class. For example, a RushOrder class inherits from an Order class. The specialized RushOrder class has special methods for priority handling and a different method for computing shipping charges, but its other methods, such as adding items and billing, are inherited from the Order class. In general, if class A extends class B, class A inherits methods from class B but has more capabilities. (We describe inheritance more fully in the next chapter, in which we discuss this important notion at some length.)

Many programmers use the UML (Unified Modeling Language) notation to draw class diagrams that describe the relationships between classes. You can see an example of such a diagram in Figure 4.2. You draw classes as rectangles, and relationships as arrows with various adornments. Table 4.1 shows the most common UML arrow styles.

4.2 Using Predefined Classes

You can’t do anything in Java without classes, and you have already seen several classes at work. However, not all of these show off the typical features of object orientation. Take, for example, the Math class. You have seen that you can use methods of the Math class, such as Math.random, without needing to know how they are implemented—all you need to know is the name and parameters (if any). That’s the point of encapsulation, and it will certainly be true of all classes. But the Math class only encapsulates functionality; it neither needs nor hides data. Since there is no data, you do not need to worry about making objects and initializing their instance fields—there aren’t any!

In the next section, we will look at a more typical class, the Date class. You will see how to construct objects and call methods of this class.

4.2.1 Objects and Object Variables

To work with objects, you first construct them and specify their initial state. Then you apply methods to the objects.

In the Java programming language, you use constructors to construct new instances. A constructor is a special method whose purpose is to construct and initialize objects. Let us look at an example. The standard Java library contains a Date class. Its objects describe points in time, such as “December 31, 1999, 23:59:59 GMT”.

![]() Note

Note

You may be wondering: Why use a class to represent dates rather than (as in some languages) a built-in type? For example, Visual Basic has a built-in date type, and programmers can specify dates in the format #6/1/1995#. On the surface, this sounds convenient—programmers can simply use the built-in date type without worrying about classes. But actually, how suitable is the Visual Basic design? In some locales, dates are specified as month/day/year, in others as day/month/year. Are the language designers really equipped to foresee these kinds of issues? If they do a poor job, the language becomes an unpleasant muddle, but unhappy programmers are powerless to do anything about it. With classes, the design task is offloaded to a library designer. If the class is not perfect, other programmers can easily write their own classes to enhance or replace the system classes. (To prove the point: The Java date library started out a bit muddled, and it has been redesigned twice.)

Constructors always have the same name as the class name. Thus, the constructor for the Date class is called Date. To construct a Date object, combine the constructor with the new operator, as follows:

new Date()

This expression constructs a new object. The object is initialized to the current date and time.

If you like, you can pass the object to a method:

System.out.println(new Date());

Alternatively, you can apply a method to the object that you just constructed. One of the methods of the Date class is the toString method. That method yields a string representation of the date. Here is how you would apply the toString method to a newly constructed Date object:

String s = new Date().toString();

In these two examples, the constructed object is used only once. Usually, you will want to hang on to the objects that you construct so that you can keep using them. Simply store the object in a variable:

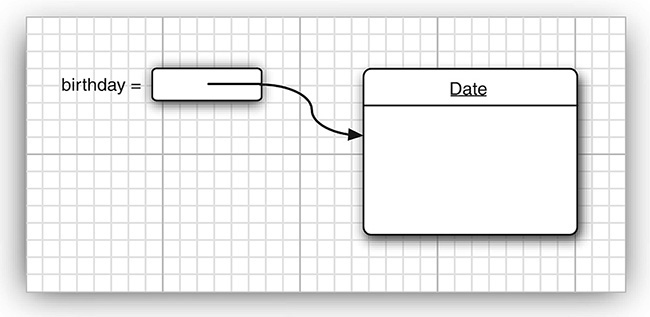

Date birthday = new Date();

Figure 4.3 shows the object variable birthday that refers to the newly constructed object.

There is an important difference between objects and object variables. For example, the statement

Date deadline; // deadline doesn't refer to any object

defines an object variable, deadline, that can refer to objects of type Date. It is important to realize that the variable deadline is not an object and, in fact, does not even refer to an object yet. You cannot use any Date methods on this variable at this time. The statement

s = deadline.toString(); // not yet

would cause a compile-time error.

You must first initialize the deadline variable. You have two choices. Of course, you can initialize the variable with a newly constructed object:

deadline = new Date();

Or you can set the variable to refer to an existing object:

deadline = birthday;

Now both variables refer to the same object (see Figure 4.4).

It is important to realize that an object variable doesn’t actually contain an object. It only refers to an object.

In Java, the value of any object variable is a reference to an object that is stored elsewhere. The return value of the new operator is also a reference. A statement such as

Date deadline = new Date();

has two parts. The expression new Date() makes an object of type Date, and its value is a reference to that newly created object. That reference is then stored in the deadline variable.

You can explicitly set an object variable to null to indicate that it currently refers to no object.

deadline = null;

...

if (deadline != null)

System.out.println(deadline);

If you apply a method to a variable that holds null, a runtime error occurs.

birthday = null;

String s = birthday.toString(); // runtime error!

Local variables are not automatically initialized to null. You must initialize them, either by calling new or by setting them to null.

Many people mistakenly believe that Java object variables behave like C++ references. But in C++ there are no null references, and references cannot be assigned. You should think of Java object variables as analogous to object pointers in C++. For example,

Date birthday; // Java

is really the same as

Date* birthday; // C++

Once you make this association, everything falls into place. Of course, a Date* pointer isn’t initialized until you initialize it with a call to new. The syntax is almost the same in C++ and Java.

Date* birthday = new Date(); // C++

If you copy one variable to another, then both variables refer to the same date—they are pointers to the same object. The equivalent of the Java null reference is the C++ NULL pointer.

All Java objects live on the heap. When an object contains another object variable, it contains just a pointer to yet another heap object.

In C++, pointers make you nervous because they are so error-prone. It is easy to create bad pointers or to mess up memory management. In Java, these problems simply go away. If you use an uninitialized pointer, the runtime system will reliably generate a runtime error instead of producing random results. You don’t have to worry about memory management, because the garbage collector takes care of it.

C++ makes quite an effort, with its support for copy constructors and assignment operators, to allow the implementation of objects that copy themselves automatically. For example, a copy of a linked list is a new linked list with the same contents but with an independent set of links. This makes it possible to design classes with the same copy behavior as the built-in types. In Java, you must use the clone method to get a complete copy of an object.

4.2.2 The LocalDate Class of the Java Library

In the preceding examples, we used the Date class that is a part of the standard Java library. An instance of the Date class has a state, namely a particular point in time.

Although you don’t need to know this when you use the Date class, the time is represented by the number of milliseconds (positive or negative) from a fixed point, the so-called epoch, which is 00:00:00 UTC, January 1, 1970. UTC is the Coordinated Universal Time, the scientific time standard which is, for practical purposes, the same as the more familiar GMT, or Greenwich Mean Time.

But as it turns out, the Date class is not very useful for manipulating the kind of calendar information that humans use for dates, such as “December 31, 1999”. This particular description of a day follows the Gregorian calendar, which is the calendar used in most countries of the world. The same point in time would be described quite differently in the Chinese or Hebrew lunar calendars, not to mention the calendar used by your customers from Mars.

![]() Note

Note

Throughout human history, civilizations grappled with the design of calendars to attach names to dates and bring order to the solar and lunar cycles. For a fascinating explanation of calendars around the world, from the French Revolutionary calendar to the Mayan long count, see Calendrical Calculations by Nachum Dershowitz and Edward M. Reingold (Cambridge University Press, 3rd ed., 2007).

The library designers decided to separate the concerns of keeping time and attaching names to points in time. Therefore, the standard Java library contains two separate classes: the Date class, which represents a point in time, and the LocalDate class, which expresses days in the familiar calendar notation. Java SE 8 introduced quite a few other classes for manipulating various aspects of date and time—see Chapter 6 of Volume II.

Separating time measurement from calendars is good object-oriented design. In general, it is a good idea to use separate classes to express different concepts.

You do not use a constructor to construct objects of the LocalDate class. Instead, use static factory methods that call constructors on your behalf. The expression

LocalDate.now()

constructs a new object that represents the date at which the object was constructed.

You can construct an object for a specific date by supplying year, month, and day:

LocalDate.of(1999, 12, 31)

Of course, you will usually want to store the constructed object in an object variable:

LocalDate newYearsEve = LocalDate.of(1999, 12, 31);

Once you have a LocalDate object, you can find out the year, month, and day with the methods getYear, getMonthValue, and getDayOfMonth:

int year = newYearsEve.getYear(); // 1999

int month = newYearsEve.getMonthValue(); // 12

int day = newYearsEve.getDayOfMonth(); // 31

This may seem pointless because they are the very same values that you just used to construct the object. But sometimes, you have a date that has been computed, and then you will want to invoke those methods to find out more about it. For example, the plusDays method yields a new LocalDate that is a given number of days away from the object to which you apply it:

LocalDate aThousandDaysLater = newYearsEve.plusDays(1000);

year = aThousandDaysLater.getYear(); // 2002

month = aThousandDaysLater.getMonthValue(); // 09

day = aThousandDaysLater.getDayOfMonth(); // 26

The LocalDate class has encapsulated instance fields to maintain the date to which it is set. Without looking at the source code, it is impossible to know the representation that the class uses internally. But, of course, the point of encapsulation is that this doesn’t matter. What matters are the methods that a class exposes.

![]() Note

Note

Actually, the Date class also has methods to get the day, month, and year, called getDay, getMonth, and getYear, but these methods are deprecated. A method is deprecated when a library designer realizes that the method should have never been introduced in the first place.

These methods were a part of the Date class before the library designers realized that it makes more sense to supply separate classes to deal with calendars. When an earlier set of calendar classes was introduced in Java 1.1, the Date methods were tagged as deprecated. You can still use them in your programs, but you will get unsightly compiler warnings if you do. It is a good idea to stay away from using deprecated methods because they may be removed in a future version of the library.

4.2.3 Mutator and Accessor Methods

Have another look at the plusDays method call that you saw in the preceding section:

LocalDate aThousandDaysLater = newYearsEve.plusDays(1000);

What happens to newYearsEve after the call? Has it been changed to be a thousand days later? As it turns out, it has not. The plusDays method yields a new LocalDate object, which is then assigned to the aThousandDaysLater variable. The original object remains unchanged. We say that the plusDays method does not mutate the object on which it is invoked. (This is similar to the toUpperCase method of the String class that you saw in Chapter 3. When you call toUpperCase on a string, that string stays the same, and a new string with uppercase characters is returned.)

An earlier version of the Java library had a different class for dealing with calendars, called GregorianCalendar. Here is how you add a thousand days to a date represented by that class:

GregorianCalendar someDay = new GregorianCalendar(1999, 11, 31);

// Odd feature of that class: month numbers go from 0 to 11

someDay.add(Calendar.DAY_OF_MONTH, 1000);

Unlike the LocalDate.plusDays method, the GregorianCalendar.add method is a mutator method. After invoking it, the state of the someDay object has changed. Here is how you can find out the new state:

year = someDay.get(Calendar.YEAR); // 2002

month = someDay.get(Calendar.MONTH) + 1; // 09

day = someDay.get(Calendar.DAY_OF_MONTH); // 26

That’s why we called the variable someDay and not newYearsEve—it no longer is new year’s eve after calling the mutator method.

In contrast, methods that only access objects without modifying them are sometimes called accessor methods. For example, LocalDate.getYear and GregorianCalendar.get are accessor methods.

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

In C++, the const suffix denotes accessor methods. A method that is not declared as const is assumed to be a mutator. However, in the Java programming language, no special syntax distinguishes accessors from mutators.

We finish this section with a program that puts the LocalDate class to work. The program displays a calendar for the current month, like this:

Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun

1

2 3 4 5 6 7 8

9 10 11 12 13 14 15

16 17 18 19 20 21 22

23 24 25 26* 27 28 29

30

The current day is marked with an asterisk (*). As you can see, the program needs to know how to compute the length of a month and the weekday of a given day.

Let us go through the key steps of the program. First, we construct an object that is initialized with the current date.

LocalDate date = LocalDate.now();

We capture the current month and day.

int month = date.getMonthValue();

int today = date.getDayOfMonth();

Then we set date to the first of the month and get the weekday of that date.

date = date.minusDays(today - 1); // Set to start of month

DayOfWeek weekday = date.getDayOfWeek();

int value = weekday.getValue(); // 1 = Monday, ... 7 = Sunday

The variable weekday is set to an object of type DayOfWeek. We call the getValue method of that object to get a numerical value for the weekday. This yields an integer that follows the international convention where the weekend comes at the end of the week, returning 11 for Monday, 2 for Tuesday, and so on. Sunday has value 7.

Note that the first line of the calendar is indented, so that the first day of the month falls on the appropriate weekday. Here is the code to print the header and the indentation for the first line:

System.out.println("Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun");

for (int i = 1; i < value; i++)

System.out.print(" ");

Now, we are ready to print the body of the calendar. We enter a loop in which date traverses the days of the month.

In each iteration, we print the date value. If date is today, the date is marked with an *. Then, we advance date to the next day. If we reach the beginning of each new week, we print a new line:

while (date.getMonthValue() == month)

{

System.out.printf("%3d", date.getDayOfMonth());

if (date.getDayOfMonth() == today)

System.out.print("*");

else

System.out.print(" ");

date = date.plusDays(1);

if (date.getDayOfWeek().getValue() == 1) System.out.println();

}

When do we stop? We don’t know whether the month has 31, 30, 29, or 28 days. Instead, we keep iterating while date is still in the current month.

Listing 4.1 shows the complete program.

As you can see, the LocalDate class makes it possible to write a calendar program that takes care of complexities such as weekdays and the varying month lengths. You don’t need to know how the LocalDate class computes months and weekdays. You just use the interface of the class—the methods such as plusDays and getDayOfWeek.

The point of this example program is to show you how you can use the interface of a class to carry out fairly sophisticated tasks without having to know the implementation details.

Listing 4.1 CalendarTest/CalendarTest.java

- 1 import java.time.*;

- 2

- 3 /**

- 4 * @version 1.5 2015-05-08

- 5 * @author Cay Horstmann

- 6 */

- 7

- 8 public class CalendarTest

- 9 {

- 10 public static void main(String[] args)

- 11 {

- 12 LocalDate date = LocalDate.now();

- 13 int month = date.getMonthValue();

- 14 int today = date.getDayOfMonth();

- 15

- 16 date = date.minusDays(today - 1); // Set to start of month

- 17 DayOfWeek weekday = date.getDayOfWeek();

- 18 int value = weekday.getValue(); // 1 = Monday, ... 7 = Sunday

- 19

- 20 System.out.println("Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun");

- 21 for (int i = 1; i < value; i++)

- 22 System.out.print(" ");

- 23 while (date.getMonthValue() == month)

- 24 {

- 25 System.out.printf("%3d", date.getDayOfMonth());

- 26 if (date.getDayOfMonth() == today)

- 27 System.out.print("*");

- 28 else

- 29 System.out.print(" ");

- 30 date = date.plusDays(1);

- 31 if (date.getDayOfWeek().getValue() == 1) System.out.println();

- 32 }

- 33 if (date.getDayOfWeek().getValue() != 1) System.out.println();

- 34 }

- 35 }

4.3 Defining Your Own Classes

In Chapter 3, you started writing simple classes. However, all those classes had just a single main method. Now the time has come to show you how to write the kind of “workhorse classes” that are needed for more sophisticated applications. These classes typically do not have a main method. Instead, they have their own instance fields and methods. To build a complete program, you combine several classes, one of which has a main method.

4.3.1 An Employee Class

The simplest form for a class definition in Java is

class ClassName

{

field1

field2

...

constructor1

constructor2

...

method1

method2

...

}

Consider the following, very simplified, version of an Employee class that might be used by a business in writing a payroll system.

class Employee

{

// instance fields

private String name;

private double salary;

private LocalDate hireDay;

// constructor

public Employee(String n, double s, int year, int month, int day)

{

name = n;

salary = s;

hireDay = LocalDate.of(year, month, day);

}

// a method

public String getName()

{

return name;

}

// more methods

...

}

We break down the implementation of this class, in some detail, in the sections that follow. First, though, Listing 4.2 is a program that shows the Employee class in action.

In the program, we construct an Employee array and fill it with three employee objects:

Employee[] staff = new Employee[3];

staff[0] = new Employee("Carl Cracker", . . .);

staff[1] = new Employee("Harry Hacker", . . .);

staff[2] = new Employee("Tony Tester", . . .);

Next, we use the raiseSalary method of the Employee class to raise each employee’s salary by 5%:

for (Employee e : staff)

e.raiseSalary(5);

Finally, we print out information about each employee, by calling the getName, getSalary, and getHireDay methods:

for (Employee e : staff)

System.out.println("name=" + e.getName()

+ ",salary=" + e.getSalary()

+ ",hireDay=" + e.getHireDay());

Note that the example program consists of two classes: the Employee class and a class EmployeeTest with the public access specifier. The main method with the instructions that we just described is contained in the EmployeeTest class.

The name of the source file is EmployeeTest.java because the name of the file must match the name of the public class. You can only have one public class in a source file, but you can have any number of nonpublic classes.

Next, when you compile this source code, the compiler creates two class files in the directory: EmployeeTest.class and Employee.class.

You then start the program by giving the bytecode interpreter the name of the class that contains the main method of your program:

java EmployeeTest

The bytecode interpreter starts running the code in the main method in the EmployeeTest class. This code in turn constructs three new Employee objects and shows you their state.

Listing 4.2 EmployeeTest/EmployeeTest.java

1 import java.time.*;

2

3 /**

4 * This program tests the Employee class.

5 * @version 1.12 2015-05-08

6 * @author Cay Horstmann

7 */

8 public class EmployeeTest

9 {

10 public static void main(String[] args)

11 {

12 // fill the staff array with three Employee objects

13 Employee[] staff = new Employee[3];

14

15 staff[0] = new Employee("Carl Cracker", 75000, 1987, 12, 15);

16 staff[1] = new Employee("Harry Hacker", 50000, 1989, 10, 1);

17 staff[2] = new Employee("Tony Tester", 40000, 1990, 3, 15);

18

19 // raise everyone's salary by 5%

20 for (Employee e : staff)

21 e.raiseSalary(5);

22

23 // print out information about all Employee objects

24 for (Employee e : staff)

25 System.out.println("name=" + e.getName() + ",salary=" + e.getSalary() + ",hireDay="

26 + e.getHireDay());

27 }

28 }

29

30 class Employee

31 {

32 private String name;

33 private double salary;

34 private LocalDate hireDay;

35

36 public Employee(String n, double s, int year, int month, int day)

37 {

38 name = n;

39 salary = s;

40 hireDay = LocalDate.of(year, month, day);

41 }

42

43 public String getName()

44 {

45 return name;

46 }

47

48 public double getSalary()

49 {

50 return salary;

51 }

52

53 public LocalDate getHireDay()

54 {

55 return hireDay;

56 }

57

58 public void raiseSalary(double byPercent)

59 {

60 double raise = salary * byPercent / 100;

61 salary += raise;

62 }

63 }

4.3.2 Use of Multiple Source Files

The program in Listing 4.2 has two classes in a single source file. Many programmers prefer to put each class into its own source file. For example, you can place the Employee class into a file Employee.java and the EmployeeTest class into EmployeeTest.java.

If you like this arrangement, you have two choices for compiling the program. You can invoke the Java compiler with a wildcard:

javac Employee*.java

Then, all source files matching the wildcard will be compiled into class files. Or, you can simply type

javac EmployeeTest.java

You may find it surprising that the second choice works even though the Employee.java file is never explicitly compiled. However, when the Java compiler sees the Employee class being used inside EmployeeTest.java, it will look for a file named Employee.class. If it does not find that file, it automatically searches for Employee.java and compiles it. Moreover, if the timestamp of the version of Employee.java that it finds is newer than that of the existing Employee.class file, the Java compiler will automatically recompile the file.

![]() Note

Note

If you are familiar with the make facility of UNIX (or one of its Windows cousins, such as nmake), then you can think of the Java compiler as having the make functionality already built in.

4.3.3 Dissecting the Employee Class

In the sections that follow, we will dissect the Employee class. Let’s start with the methods in this class. As you can see by examining the source code, this class has one constructor and four methods:

public Employee(String n, double s, int year, int month, int day)

public String getName()

public double getSalary()

public LocalDate getHireDay()

public void raiseSalary(double byPercent)

All methods of this class are tagged as public. The keyword public means that any method in any class can call the method. (The four possible access levels are covered in this and the next chapter.)

Next, notice the three instance fields that will hold the data manipulated inside an instance of the Employee class.

private String name;

private double salary;

private LocalDate hireDay;

The private keyword makes sure that the only methods that can access these instance fields are the methods of the Employee class itself. No outside method can read or write to these fields.

![]() Note

Note

You could use the public keyword with your instance fields, but it would be a very bad idea. Having public data fields would allow any part of the program to read and modify the instance fields, completely ruining encapsulation. Any method of any class can modify public fields—and, in our experience, some code will take advantage of that access privilege when you least expect it. We strongly recommend to make all your instance fields private.

Finally, notice that two of the instance fields are themselves objects: The name and hireDay fields are references to String and LocalDate objects. This is quite usual: Classes will often contain instance fields of class type.

4.3.4 First Steps with Constructors

Let’s look at the constructor listed in our Employee class.

public Employee(String n, double s, int year, int month, int day)

{

name = n;

salary = s;

hireDay = LocalDate.of(year, month, day);

}

As you can see, the name of the constructor is the same as the name of the class. This constructor runs when you construct objects of the Employee class—giving the instance fields the initial state you want them to have.

For example, when you create an instance of the Employee class with code like this:

new Employee("James Bond", 100000, 1950, 1, 1)

you have set the instance fields as follows:

name = "James Bond";

salary = 100000;

hireDay = LocalDate.of(1950, 1, 1); // January 1, 1950

There is an important difference between constructors and other methods. A constructor can only be called in conjunction with the new operator. You can’t apply a constructor to an existing object to reset the instance fields. For example,

james.Employee("James Bond", 250000, 1950, 1, 1) // ERROR

is a compile-time error.

We will have more to say about constructors later in this chapter. For now, keep the following in mind:

• A constructor has the same name as the class.

• A class can have more than one constructor.

• A constructor can take zero, one, or more parameters.

• A constructor has no return value.

• A constructor is always called with the new operator.

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

Constructors work the same way in Java as they do in C++. Keep in mind, however, that all Java objects are constructed on the heap and that a constructor must be combined with new. It is a common error of C++ programmers to forget the new operator:

Employee number007("James Bond", 100000, 1950, 1, 1);

// C++, not Java

That works in C++ but not in Java.

![]() Caution

Caution

Be careful not to introduce local variables with the same names as the instance fields. For example, the following constructor will not set the salary:

public Employee(String n, double s, . . .)

{

String name = n; // Error

double salary = s; // Error

...

}

The constructor declares local variables name and salary. These variables are only accessible inside the constructor. They shadow the instance fields with the same name. Some programmers accidentally write this kind of code when they type faster than they think, because their fingers are used to adding the data type. This is a nasty error that can be hard to track down. You just have to be careful in all of your methods to not use variable names that equal the names of instance fields.

4.3.5 Implicit and Explicit Parameters

Methods operate on objects and access their instance fields. For example, the method

public void raiseSalary(double byPercent)

{

double raise = salary * byPercent / 100;

salary += raise;

}

sets a new value for the salary instance field in the object on which this method is invoked. Consider the call

number007.raiseSalary(5);

The effect is to increase the value of the number007.salary field by 5%. More specifically, the call executes the following instructions:

double raise = number007.salary * 5 / 100;

number007.salary += raise;

The raiseSalary method has two parameters. The first parameter, called the implicit parameter, is the object of type Employee that appears before the method name. The second parameter, the number inside the parentheses after the method name, is an explicit parameter. (Some people call the implicit parameter the target or receiver of the method call.)

As you can see, the explicit parameters are explicitly listed in the method declaration, for example, double byPercent. The implicit parameter does not appear in the method declaration.

In every method, the keyword this refers to the implicit parameter. If you like, you can write the raiseSalary method as follows:

public void raiseSalary(double byPercent)

{

double raise = this.salary * byPercent / 100;

this.salary += raise;

}

Some programmers prefer that style because it clearly distinguishes between instance fields and local variables.

In C++, you generally define methods outside the class:

void Employee::raiseSalary(double byPercent) // C++, not Java

{

...

}

If you define a method inside a class, then it is, automatically, an inline method.

class Employee

{

...

int getName() { return name; } // inline in C++

}

In Java, all methods are defined inside the class itself. This does not make them inline. Finding opportunities for inline replacement is the job of the Java virtual machine. The just-in-time compiler watches for calls to methods that are short, commonly called, and not overridden, and optimizes them away.

4.3.6 Benefits of Encapsulation

Finally, let’s look more closely at the rather simple getName, getSalary, and getHireDay methods.

public String getName()

{

return name;

}

public double getSalary()

{

return salary;

}

public LocalDate getHireDay()

{

return hireDay;

}

These are obvious examples of accessor methods. As they simply return the values of instance fields, they are sometimes called field accessors.

Wouldn’t it be easier to make the name, salary, and hireDay fields public, instead of having separate accessor methods?

However, the name field is a read-only field. Once you set it in the constructor, there is no method to change it. Thus, we have a guarantee that the name field will never be corrupted.

The salary field is not read-only, but it can only be changed by the raiseSalary method. In particular, should the value ever turn out wrong, only that method needs to be debugged. Had the salary field been public, the culprit for messing up the value could have been anywhere.

Sometimes, it happens that you want to get and set the value of an instance field. Then you need to supply three items:

• A private data field;

• A public field accessor method; and

• A public field mutator method.

This is a lot more tedious than supplying a single public data field, but there are considerable benefits.

First, you can change the internal implementation without affecting any code other than the methods of the class. For example, if the storage of the name is changed to

String firstName;

String lastName;

then the getName method can be changed to return

firstName + " " + lastName

This change is completely invisible to the remainder of the program.

Of course, the accessor and mutator methods may need to do a lot of work and convert between the old and the new data representation. That leads us to our second benefit: Mutator methods can perform error checking, whereas code that simply assigns to a field may not go into the trouble. For example, a setSalary method might check that the salary is never less than 0.

![]() Caution

Caution

Be careful not to write accessor methods that return references to mutable objects. In a previous edition of this book, we violated that rule in our Employee class in which the getHireDay method returned an object of class Date:

class Employee

{

private Date hireDay;

...

public Date getHireDay()

{

return hireDay; // Bad

}

...

}

Unlike the LocalDate class, which has no mutator methods, the Date class has a mutator method, setTime, where you can set the number of milliseconds.

The fact that Date objects are mutable breaks encapsulation! Consider the following rogue code:

Employee harry = . . .;

Date d = harry.getHireDay();

double tenYearsInMilliSeconds = 10 * 365.25 * 24 * 60 * 60 * 1000;

d.setTime(d.getTime() - (long) tenYearsInMilliSeconds);

// let's give Harry ten years of added seniority

The reason is subtle. Both d and harry.hireDay refer to the same object (see Figure 4.5). Applying mutator methods to d automatically changes the private state of the employee object!

If you need to return a reference to a mutable object, you should clone it first. A clone is an exact copy of an object stored in a new location. We discuss cloning in detail in Chapter 6. Here is the corrected code:

class Employee

{

...

public Date getHireDay()

{

return (Date) hireDay.clone(); // Ok

}

...

}

As a rule of thumb, always use clone whenever you need to return a copy of a mutable field.

4.3.7 Class-Based Access Privileges

You know that a method can access the private data of the object on which it is invoked. What many people find surprising is that a method can access the private data of all objects of its class. For example, consider a method equals that compares two employees.

class Employee

{

...

public boolean equals(Employee other)

{

return name.equals(other.name);

}

}

A typical call is

if (harry.equals(boss)) . . .

This method accesses the private fields of harry, which is not surprising. It also accesses the private fields of boss. This is legal because boss is an object of type Employee, and a method of the Employee class is permitted to access the private fields of any object of type Employee.

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

C++ has the same rule. A method can access the private features of any object of its class, not just of the implicit parameter.

4.3.8 Private Methods

When implementing a class, we make all data fields private because public data are dangerous. But what about the methods? While most methods are public, private methods are useful in certain circumstances. Sometimes, you may wish to break up the code for a computation into separate helper methods. Typically, these helper methods should not be part of the public interface—they may be too close to the current implementation or require a special protocol or calling order. Such methods are best implemented as private.

To implement a private method in Java, simply change the public keyword to private.

By making a method private, you are under no obligation to keep it available if you change your implementation. The method may well be harder to implement or unnecessary if the data representation changes; this is irrelevant. The point is that as long as the method is private, the designers of the class can be assured that it is never used outside the other class, so they can simply drop it. If a method is public, you cannot simply drop it because other code might rely on it.

4.3.9 Final Instance Fields

You can define an instance field as final. Such a field must be initialized when the object is constructed. That is, you must guarantee that the field value has been set after the end of every constructor. Afterwards, the field may not be modified again. For example, the name field of the Employee class may be declared as final because it never changes after the object is constructed—there is no setName method.

class Employee

{

private final String name;

...

}

The final modifier is particularly useful for fields whose type is primitive or an immutable class. (A class is immutable if none of its methods ever mutate its objects. For example, the String class is immutable.)

For mutable classes, the final modifier can be confusing. For example, consider a field

private final StringBuilder evaluations;

that is initialized in the Employee constructor as

evaluations = new StringBuilder();

The final keyword merely means that the object reference stored in the evaluations variable will never again refer to a different StringBuilder object. But the object can be mutated:

public void giveGoldStar()

{

evaluations.append(LocalDate.now() + ": Gold star!

");

}

4.4 Static Fields and Methods

In all sample programs that you have seen, the main method is tagged with the static modifier. We are now ready to discuss the meaning of this modifier.

4.4.1 Static Fields

If you define a field as static, then there is only one such field per class. In contrast, each object has its own copy of all instance fields. For example, let’s suppose we want to assign a unique identification number to each employee. We add an instance field id and a static field nextId to the Employee class:

class Employee

{

private static int nextId = 1;

private int id;

...

}

Every employee object now has its own id field, but there is only one nextId field that is shared among all instances of the class. Let’s put it another way. If there are 1,000 objects of the Employee class, then there are 1,000 instance fields id, one for each object. But there is a single static field nextId. Even if there are no employee objects, the static field nextId is present. It belongs to the class, not to any individual object.

![]() Note

Note

In some object-oriented programming languages, static fields are called class fields. The term “static” is a meaningless holdover from C++.

Let’s implement a simple method:

public void setId()

{

id = nextId;

nextId++;

}

Suppose you set the employee identification number for harry:

harry.setId();

Then, the id field of harry is set to the current value of the static field nextId, and the value of the static field is incremented:

harry.id = Employee.nextId;

Employee.nextId++;

4.4.2 Static Constants

Static variables are quite rare. However, static constants are more common. For example, the Math class defines a static constant:

public class Math

{

...

public static final double PI = 3.14159265358979323846;

...

}

You can access this constant in your programs as Math.PI.

If the keyword static had been omitted, then PI would have been an instance field of the Math class. That is, you would need an object of this class to access PI, and every Math object would have its own copy of PI.

Another static constant that you have used many times is System.out. It is declared in the System class as follows:

public class System

{

...

public static final PrintStream out = . . .;

...

}

As we mentioned several times, it is never a good idea to have public fields, because everyone can modify them. However, public constants (that is, final fields) are fine. Since out has been declared as final, you cannot reassign another print stream to it:

System.out = new PrintStream(. . .); // Error--out is final

![]() Note

Note

If you look at the System class, you will notice a method setOut that sets System.out to a different stream. You may wonder how that method can change the value of a final variable. However, the setOut method is a native method, not implemented in the Java programming language. Native methods can bypass the access control mechanisms of the Java language. This is a very unusual workaround that you should not emulate in your programs.

4.4.3 Static Methods

Static methods are methods that do not operate on objects. For example, the pow method of the Math class is a static method. The expression

Math.pow(x, a)

computes the power xa. It does not use any Math object to carry out its task. In other words, it has no implicit parameter.

You can think of static methods as methods that don’t have a this parameter. (In a nonstatic method, the this parameter refers to the implicit parameter of the method—see Section 4.3.5, “Implicit and Explicit Parameters,” on p. 152.)

A static method of the Employee class cannot access the id instance field because it does not operate on an object. However, a static method can access a static field. Here is an example of such a static method:

public static int getNextId()

{

return nextId; // returns static field

}

To call this method, you supply the name of the class:

int n = Employee.getNextId();

Could you have omitted the keyword static for this method? Yes, but then you would need to have an object reference of type Employee to invoke the method.

![]() Note

Note

It is legal to use an object to call a static method. For example, if harry is an Employee object, then you can call harry.getNextId() instead of Employee.getNextId(). However, we find that notation confusing. The getNextId method doesn’t look at harry at all to compute the result. We recommend that you use class names, not objects, to invoke static methods.

Use static methods in two situations:

• When a method doesn’t need to access the object state because all needed parameters are supplied as explicit parameters (example: Math.pow).

• When a method only needs to access static fields of the class (example: Employee.getNextId).

Static fields and methods have the same functionality in Java and C++. However, the syntax is slightly different. In C++, you use the :: operator to access a static field or method outside its scope, such as Math::PI.

The term “static” has a curious history. At first, the keyword static was introduced in C to denote local variables that don’t go away when a block is exited. In that context, the term “static” makes sense: The variable stays around and is still there when the block is entered again. Then static got a second meaning in C, to denote global variables and functions that cannot be accessed from other files. The keyword static was simply reused, to avoid introducing a new keyword. Finally, C++ reused the keyword for a third, unrelated, interpretation—to denote variables and functions that belong to a class but not to any particular object of the class. That is the same meaning the keyword has in Java.

4.4.4 Factory Methods

Here is another common use for static methods. Classes such as LocalDate and NumberFormat use static factory methods that construct objects. You have already seen the factory methods LocalDate.now and LocalDate.of. Here is how the NumberFormat class yields formatter objects for various styles:

NumberFormat currencyFormatter = NumberFormat.getCurrencyInstance();

NumberFormat percentFormatter = NumberFormat.getPercentInstance();

double x = 0.1;

System.out.println(currencyFormatter.format(x)); // prints $0.10

System.out.println(percentFormatter.format(x)); // prints 10%

Why doesn’t the NumberFormat class use a constructor instead? There are two reasons:

• You can’t give names to constructors. The constructor name is always the same as the class name. But we want two different names to get the currency instance and the percent instance.

• When you use a constructor, you can’t vary the type of the constructed object. But the factory methods actually return objects of the class DecimalFormat, a subclass that inherits from NumberFormat. (See Chapter 5 for more on inheritance.)

4.4.5 The main Method

Note that you can call static methods without having any objects. For example, you never construct any objects of the Math class to call Math.pow.

For the same reason, the main method is a static method.

public class Application

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

// construct objects here

...

}

}

The main method does not operate on any objects. In fact, when a program starts, there aren’t any objects yet. The static main method executes, and constructs the objects that the program needs.

![]() Tip

Tip

Every class can have a main method. That is a handy trick for unit testing of classes. For example, you can add a main method to the Employee class:

class Employee

{

public Employee(String n, double s, int year, int month, int day)

{

name = n;

salary = s;

LocalDate hireDay = LocalDate.now(year, month, day);

}

...

public static void main(String[] args) // unit test

{

Employee e = new Employee("Romeo", 50000, 2003, 3, 31);

e.raiseSalary(10);

System.out.println(e.getName() + " " + e.getSalary());

}

...

}

If you want to test the Employee class in isolation, simply execute

java Employee

If the Employee class is a part of a larger application, you start the application with

java Application

and the main method of the Employee class is never executed.

The program in Listing 4.3 contains a simple version of the Employee class with a static field nextId and a static method getNextId. We fill an array with three Employee objects and then print the employee information. Finally, we print the next available identification number, to demonstrate the static method.

Note that the Employee class also has a static main method for unit testing. Try running both

java Employee

and

java StaticTest

to execute both main methods.

Listing 4.3 StaticTest/StaticTest.java

1 /**

2 * This program demonstrates static methods.

3 * @version 1.01 2004-02-19

4 * @author Cay Horstmann

5 */

6 public class StaticTest

7 {

8 public static void main(String[] args)

9 {

10 // fill the staff array with three Employee objects

11 Employee[] staff = new Employee[3];

12

13 staff[0] = new Employee("Tom", 40000);

14 staff[1] = new Employee("Dick", 60000);

15 staff[2] = new Employee("Harry", 65000);

16

17 // print out information about all Employee objects

18 for (Employee e : staff)

19 {

20 e.setId();

21 System.out.println("name=" + e.getName() + ",id=" + e.getId() + ",salary="

22 + e.getSalary());

23 }

24

25 int n = Employee.getNextId(); // calls static method

26 System.out.println("Next available id=" + n);

27 }

28 }

29

30 class Employee

31 {

32 private static int nextId = 1;

33

34 private String name;

35 private double salary;

36 private int id;

37

38 public Employee(String n, double s)

39 {

40 name = n;

41 salary = s;

42 id = 0;

43 }

44

45 public String getName()

46 {

47 return name;

48 }

49

50 public double getSalary()

51 {

52 return salary;

53 }

54

55 public int getId()

56 {

57 return id;

58 }

59

60 public void setId()

61 {

62 id = nextId; // set id to next available id

63 nextId++;

64 }

65

66 public static int getNextId()

67 {

68 return nextId; // returns static field

69 }

70

71 public static void main(String[] args) // unit test

72 {

73 Employee e = new Employee("Harry", 50000);

74 System.out.println(e.getName() + " " + e.getSalary());

75 }

76 }

4.5 Method Parameters

Let us review the computer science terms that describe how parameters can be passed to a method (or a function) in a programming language. The term call by value means that the method gets just the value that the caller provides. In contrast, call by reference means that the method gets the location of the variable that the caller provides. Thus, a method can modify the value stored in a variable passed by reference but not in one passed by value. These “call by . . .” terms are standard computer science terminology describing the behavior of method parameters in various programming languages, not just Java. (There is also a call by name that is mainly of historical interest, being employed in the Algol programming language, one of the oldest high-level languages.)

The Java programming language always uses call by value. That means that the method gets a copy of all parameter values. In particular, the method cannot modify the contents of any parameter variables passed to it.

For example, consider the following call:

double percent = 10;

harry.raiseSalary(percent);

No matter how the method is implemented, we know that after the method call, the value of percent is still 10.

Let us look a little more closely at this situation. Suppose a method tried to triple the value of a method parameter:

public static void tripleValue(double x) // doesn't work

{

x = 3 * x;

}

Let’s call this method:

double percent = 10;

tripleValue(percent);

However, this does not work. After the method call, the value of percent is still 10. Here is what happens:

1. x is initialized with a copy of the value of percent (that is, 10).

2. x is tripled—it is now 30. But percent is still 10 (see Figure 4.6).

3. The method ends, and the parameter variable x is no longer in use.

There are, however, two kinds of method parameters:

• Primitive types (numbers, boolean values)

• Object references

You have seen that it is impossible for a method to change a primitive type parameter. The situation is different for object parameters. You can easily implement a method that triples the salary of an employee:

public static void tripleSalary(Employee x) // works

{

x.raiseSalary(200);

}

When you call

harry = new Employee(. . .);

tripleSalary(harry);

then the following happens:

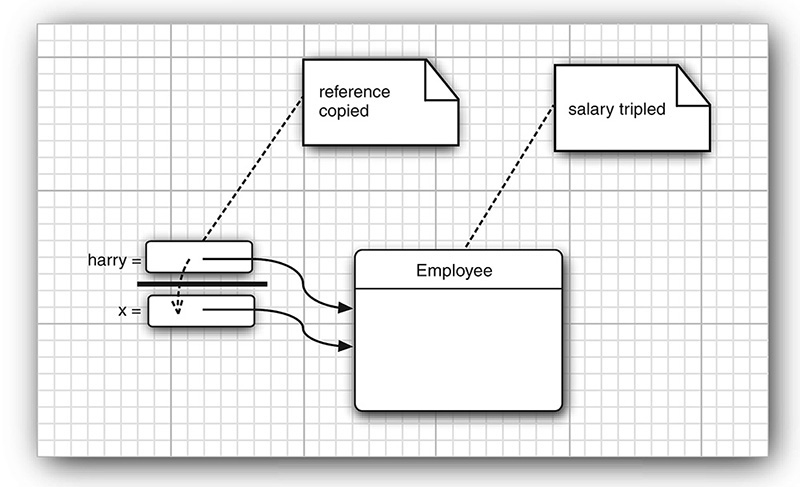

1. x is initialized with a copy of the value of harry, that is, an object reference.

2. The raiseSalary method is applied to that object reference. The Employee object to which both x and harry refer gets its salary raised by 200 percent.

3. The method ends, and the parameter variable x is no longer in use. Of course, the object variable harry continues to refer to the object whose salary was tripled (see Figure 4.7).

As you have seen, it is easily possible—and in fact very common—to implement methods that change the state of an object parameter. The reason is simple. The method gets a copy of the object reference, and both the original and the copy refer to the same object.

Many programming languages (in particular, C++ and Pascal) have two mechanisms for parameter passing: call by value and call by reference. Some programmers (and unfortunately even some book authors) claim that Java uses call by reference for objects. That is false. As this is such a common misunderstanding, it is worth examining a counterexample in detail.

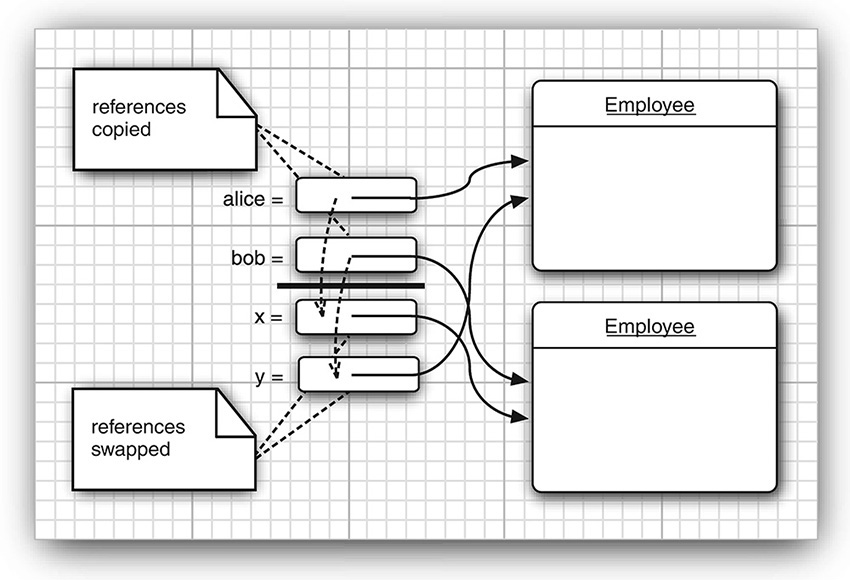

Let’s try to write a method that swaps two employee objects:

public static void swap(Employee x, Employee y) // doesn't work

{

Employee temp = x;

x = y;

y = temp;

}

If Java used call by reference for objects, this method would work:

Employee a = new Employee("Alice", . . .);

Employee b = new Employee("Bob", . . .);

swap(a, b);

// does a now refer to Bob, b to Alice?

However, the method does not actually change the object references that are stored in the variables a and b. The x and y parameters of the swap method are initialized with copies of these references. The method then proceeds to swap these copies.

// x refers to Alice, y to Bob

Employee temp = x;

x = y;

y = temp;

// now x refers to Bob, y to Alice

But ultimately, this is a wasted effort. When the method ends, the parameter variables x and y are abandoned. The original variables a and b still refer to the same objects as they did before the method call (see Figure 4.8).

This demonstrates that the Java programming language does not use call by reference for objects. Instead, object references are passed by value.

Here is a summary of what you can and cannot do with method parameters in Java:

• A method cannot modify a parameter of a primitive type (that is, numbers or boolean values).

• A method can change the state of an object parameter.

• A method cannot make an object parameter refer to a new object.

The program in Listing 4.4 demonstrates these facts. The program first tries to triple the value of a number parameter and does not succeed:

Testing tripleValue:

Before: percent=10.0

End of method: x=30.0

After: percent=10.0

It then successfully triples the salary of an employee:

Testing tripleSalary:

Before: salary=50000.0

End of method: salary=150000.0

After: salary=150000.0

After the method, the state of the object to which harry refers has changed. This is possible because the method modified the state through a copy of the object reference.

Finally, the program demonstrates the failure of the swap method:

Testing swap:

Before: a=Alice

Before: b=Bob

End of method: x=Bob

End of method: y=Alice

After: a=Alice

After: b=Bob

As you can see, the parameter variables x and y are swapped, but the variables a and b are not affected.

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

C++ has both call by value and call by reference. You tag reference parameters with &. For example, you can easily implement methods void tripleValue(double& x) or void swap(Employee& x, Employee& y) that modify their reference parameters.

Listing 4.4 ParamTest/ParamTest.java

1 /**

2 * This program demonstrates parameter passing in Java.

3 * @version 1.00 2000-01-27

4 * @author Cay Horstmann

5 */

6 public class ParamTest

7 {

8 public static void main(String[] args)

9 {

10 /*

11 * Test 1: Methods can't modify numeric parameters

12 */

13 System.out.println("Testing tripleValue:");

14 double percent = 10;

15 System.out.println("Before: percent=" + percent);

16 tripleValue(percent);

17 System.out.println("After: percent=" + percent);

18

19 /*

20 * Test 2: Methods can change the state of object parameters

21 */

22 System.out.println("

Testing tripleSalary:");

23 Employee harry = new Employee("Harry", 50000);

24 System.out.println("Before: salary=" + harry.getSalary());

25 tripleSalary(harry);

26 System.out.println("After: salary=" + harry.getSalary());

27

28 /*

29 * Test 3: Methods can't attach new objects to object parameters

30 */

31 System.out.println("

Testing swap:");

32 Employee a = new Employee("Alice", 70000);

33 Employee b = new Employee("Bob", 60000);

34 System.out.println("Before: a=" + a.getName());

35 System.out.println("Before: b=" + b.getName());

36 swap(a, b);

37 System.out.println("After: a=" + a.getName());

38 System.out.println("After: b=" + b.getName());

39 }

40

41 public static void tripleValue(double x) // doesn't work

42 {

43 x = 3 * x;

44 System.out.println("End of method: x=" + x);

45 }

46

47 public static void tripleSalary(Employee x) // works

48 {

49 x.raiseSalary(200);

50 System.out.println("End of method: salary=" + x.getSalary());

51 }

52

53 public static void swap(Employee x, Employee y)

54 {

55 Employee temp = x;

56 x = y;

57 y = temp;

58 System.out.println("End of method: x=" + x.getName());

59 System.out.println("End of method: y=" + y.getName());

60 }

61 }

62

63 class Employee // simplified Employee class

64 {

65 private String name;

66 private double salary;

67

68 public Employee(String n, double s)

69 {

70 name = n;

71 salary = s;

72 }

73

74 public String getName()

75 {

76 return name;

77 }

78

79 public double getSalary()

80 {

81 return salary;

82 }

83

84 public void raiseSalary(double byPercent)

85 {

86 double raise = salary * byPercent / 100;

87 salary += raise;

88 }

89 }

4.6 Object Construction

You have seen how to write simple constructors that define the initial state of your objects. However, since object construction is so important, Java offers quite a variety of mechanisms for writing constructors. We go over these mechanisms in the sections that follow.

4.6.1 Overloading

Some classes have more than one constructor. For example, you can construct an empty StringBuilder object as

StringBuilder messages = new StringBuilder();

Alternatively, you can specify an initial string:

StringBuilder todoList = new StringBuilder("To do: ");

This capability is called overloading. Overloading occurs if several methods have the same name (in this case, the StringBuilder constructor method) but different parameters. The compiler must sort out which method to call. It picks the correct method by matching the parameter types in the headers of the various methods with the types of the values used in the specific method call. A compile-time error occurs if the compiler cannot match the parameters, either because there is no match at all or because there there is not one that is better than all others. (The process of finding a match is called overloading resolution.)

![]() Note

Note

Java allows you to overload any method—not just constructor methods. Thus, to completely describe a method, you need to specify its name together with its parameter types. This is called the signature of the method. For example, the String class has four public methods called indexOf. They have signatures

indexOf(int)

indexOf(int, int)

indexOf(String)

indexOf(String, int)

The return type is not part of the method signature. That is, you cannot have two methods with the same names and parameter types but different return types.

4.6.2 Default Field Initialization

If you don’t set a field explicitly in a constructor, it is automatically set to a default value: numbers to 0, boolean values to false, and object references to null. Some people consider it poor programming practice to rely on the defaults. Certainly, it makes it harder for someone to understand your code if fields are being initialized invisibly.

![]() Note

Note

This is an important difference between fields and local variables. You must always explicitly initialize local variables in a method. But in a class, if you don’t initialize a field, it is automatically initialized to a default (0, false, or null).

For example, consider the Employee class. Suppose you don’t specify how to initialize some of the fields in a constructor. By default, the salary field would be initialized with 0 and the name and hireDay fields would be initialized with null.

However, that would not be a good idea. If anyone called the getName or getHireDay method, they would get a null reference that they probably don’t expect:

LocalDate h = harry.getHireDay();

int year = h.getYear(); // throws exception if h is null

4.6.3 The Constructor with No Arguments

Many classes contain a constructor with no arguments that creates an object whose state is set to an appropriate default. For example, here is a constructor with no arguments for the Employee class:

public Employee()

{

name = "";

salary = 0;

hireDay = LocalDate.now();

}

If you write a class with no constructors whatsoever, then a no-argument constructor is provided for you. This constructor sets all the instance fields to their default values. So, all numeric data contained in the instance fields would be 0, all boolean values would be false, and all object variables would be set to null.

If a class supplies at least one constructor but does not supply a no-argument constructor, it is illegal to construct objects without supplying arguments. For example, our original Employee class in Listing 4.2 provided a single constructor:

Employee(String name, double salary, int y, int m, int d)

With that class, it was not legal to construct default employees. That is, the call

e = new Employee();

would have been an error.

Please keep in mind that you get a free no-argument constructor only when your class has no other constructors. If you write your class with even a single constructor of your own and you want the users of your class to have the ability to create an instance by a call to

new ClassName()

then you must provide a no-argument constructor. Of course, if you are happy with the default values for all fields, you can simply supply

public ClassName()

{

}

4.6.4 Explicit Field Initialization

By overloading the constructor methods in a class, you can build many ways to set the initial state of the instance fields of your classes. It is always a good idea to make sure that, regardless of the constructor call, every instance field is set to something meaningful.

You can simply assign a value to any field in the class definition. For example:

class Employee

{

private String name = "";

...

}

This assignment is carried out before the constructor executes. This syntax is particularly useful if all constructors of a class need to set a particular instance field to the same value.

The initialization value doesn’t have to be a constant value. Here is an example in which a field is initialized with a method call. Consider an Employee class where each employee has an id field. You can initialize it as follows:

class Employee

{

private static int nextId;

private int id = assignId();

...

private static int assignId()

{

int r = nextId;

nextId++;

return r;

}

...

}

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

In C++, you cannot directly initialize instance fields of a class. All fields must be set in a constructor. However, C++ has a special initializer list syntax, such as

Employee::Employee(String n, double s, int y, int m, int d) // C++

: name(n),

salary(s),

hireDay(y, m, d)

{

}

C++ uses this special syntax to call field constructors. In Java, there is no need for that because objects have no subobjects, only pointers to other objects.

4.6.5 Parameter Names

When you write very trivial constructors (and you’ll write a lot of them), it can be somewhat frustrating to come up with parameter names.

We have generally opted for single-letter parameter names:

public Employee(String n, double s)

{

name = n;

salary = s;

}

However, the drawback is that you need to read the code to tell what the n and s parameters mean.

Some programmers prefix each parameter with an “a”:

public Employee(String aName, double aSalary)

{

name = aName;

salary = aSalary;

}

That is quite neat. Any reader can immediately figure out the meaning of the parameters.

Another commonly used trick relies on the fact that parameter variables shadow instance fields with the same name. For example, if you call a parameter salary, then salary refers to the parameter, not the instance field. But you can still access the instance field as this.salary. Recall that this denotes the implicit parameter, that is, the object being constructed. Here is an example:

public Employee(String name, double salary)

{

this.name = name;

this.salary = salary;

}

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

In C++, it is common to prefix instance fields with an underscore or a fixed letter. (The letters m and x are common choices.) For example, the salary field might be called _salary, mSalary, or xSalary. Java programmers don’t usually do that.

4.6.6 Calling Another Constructor

The keyword this refers to the implicit parameter of a method. However, this keyword has a second meaning.

If the first statement of a constructor has the form this(. . .), then the constructor calls another constructor of the same class. Here is a typical example:

public Employee(double s)

{

// calls Employee(String, double)

this("Employee #" + nextId, s);

nextId++;

}

When you call new Employee(60000), the Employee(double) constructor calls the Employee(String, double) constructor.

Using the this keyword in this manner is useful—you only need to write common construction code once.

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

The this reference in Java is identical to the this pointer in C++. However, in C++ it is not possible for one constructor to call another. If you want to factor out common initialization code in C++, you must write a separate method.

• By setting a value in a constructor

• By assigning a value in the declaration

There is a third mechanism in Java, called an initialization block. Class declarations can contain arbitrary blocks of code. These blocks are executed whenever an object of that class is constructed. For example:

class Employee

{

private static int nextId;

private int id;

private String name;

private double salary;

// object initialization block

{

id = nextId;

nextId++;

}

public Employee(String n, double s)

{

name = n;

salary = s;

}

public Employee()

{

name = "";

salary = 0;

}

...

}