Chapter 1. An Introduction to Java

In this chapter

• 1.1 Java as a Programming Platform

• 1.2 The Java ‘White Paper’ Buzzwords

• 1.3 Java Applets and the Internet

• 1.5 Common Misconceptions about Java

The first release of Java in 1996 generated an incredible amount of excitement, not just in the computer press, but in mainstream media such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and BusinessWeek. Java has the distinction of being the first and only programming language that had a ten-minute story on National Public Radio. A $100,000,000 venture capital fund was set up solely for products using a specific computer language. I hope you will enjoy the brief history of Java that you will find in this chapter.

1.1 Java as a Programming Platform

In the first edition of this book, my coauthor Gary Cornell and I had this to write about Java:

“As a computer language, Java’s hype is overdone: Java is certainly a good programming language. There is no doubt that it is one of the better languages available to serious programmers. We think it could potentially have been a great programming language, but it is probably too late for that. Once a language is out in the field, the ugly reality of compatibility with existing code sets in.”

Our editor got a lot of flack for this paragraph from someone very high up at Sun Microsystems, the company that originally developed Java. The Java language has a lot of nice features that we will examine in detail later in this chapter. It has its share of warts, and some of the newer additions to the language are not as elegant as the original features because of the ugly reality of compatibility.

But, as we already said in the first edition, Java was never just a language. There are lots of programming languages out there, but few of them make much of a splash. Java is a whole platform, with a huge library, containing lots of reusable code, and an execution environment that provides services such as security, portability across operating systems, and automatic garbage collection.

As a programmer, you will want a language with a pleasant syntax and comprehensible semantics (i.e., not C++). Java fits the bill, as do dozens of other fine languages. Some languages give you portability, garbage collection, and the like, but they don’t have much of a library, forcing you to roll your own if you want fancy graphics or networking or database access. Well, Java has everything—a good language, a high-quality execution environment, and a vast library. That combination is what makes Java an irresistible proposition to so many programmers.

1.2 The Java “White Paper” Buzzwords

The authors of Java wrote an influential white paper that explains their design goals and accomplishments. They also published a shorter overview that is organized along the following 11 buzzwords:

1. Simple

2. Object-Oriented

3. Distributed

4. Robust

5. Secure

6. Architecture-Neutral

7. Portable

8. Interpreted

9. High-Performance

11. Dynamic

In this section, you will find a summary, with excerpts from the white paper, of what the Java designers say about each buzzword, together with a commentary based on my experiences with the current version of Java.

![]() Note

Note

The white paper can be found at www.oracle.com/technetwork/java/langenv-140151.html. You can retrieve the overview with the 11 buzzwords at http://horstmann.com/corejava/java-an-overview/7Gosling.pdf.

1.2.1 Simple

We wanted to build a system that could be programmed easily without a lot of esoteric training and which leveraged today’s standard practice. So even though we found that C++ was unsuitable, we designed Java as closely to C++ as possible in order to make the system more comprehensible. Java omits many rarely used, poorly understood, confusing features of C++ that, in our experience, bring more grief than benefit.

The syntax for Java is, indeed, a cleaned-up version of C++ syntax. There is no need for header files, pointer arithmetic (or even a pointer syntax), structures, unions, operator overloading, virtual base classes, and so on. (See the C++ notes interspersed throughout the text for more on the differences between Java and C++.) The designers did not, however, attempt to fix all of the clumsy features of C++. For example, the syntax of the switch statement is unchanged in Java. If you know C++, you will find the transition to the Java syntax easy.

At the time that Java was released, C++ was actually not the most commonly used programming language. Many developers used Visual Basic and its drag-and-drop programming environment. These developers did not find Java simple. It took several years for Java development environments to catch up. Nowadays, Java development environments are far ahead of those for most other programming languages.

Another aspect of being simple is being small. One of the goals of Java is to enable the construction of software that can run stand-alone on small machines. The size of the basic interpreter and class support is about 40K; the basic standard libraries and thread support (essentially a self-contained microkernel) add another 175K.

This was a great achievement at the time. Of course, the library has since grown to huge proportions. There is now a separate Java Micro Edition with a smaller library, suitable for embedded devices.

1.2.2 Object-Oriented

Simply stated, object-oriented design is a programming technique that focuses on the data (= objects) and on the interfaces to that object. To make an analogy with carpentry, an “object-oriented” carpenter would be mostly concerned with the chair he is building, and secondarily with the tools used to make it; a “non-object-oriented” carpenter would think primarily of his tools. The object-oriented facilities of Java are essentially those of C++.

Object orientation was pretty well established when Java was developed. The object-oriented features of Java are comparable to those of C++. The major difference between Java and C++ lies in multiple inheritance, which Java has replaced with the simpler concept of interfaces. Java has a richer capacity for runtime introspection than C++ (which is discussed in Chapter 5).

1.2.3 Distributed

Java has an extensive library of routines for coping with TCP/IP protocols like HTTP and FTP. Java applications can open and access objects across the Net via URLs with the same ease as when accessing a local file system.

Nowadays, one takes this for granted, but in 1995, connecting to a web server from a C++ or Visual Basic program was a major undertaking.

1.2.4 Robust

Java is intended for writing programs that must be reliable in a variety of ways. Java puts a lot of emphasis on early checking for possible problems, later dynamic (runtime) checking, and eliminating situations that are error-prone. . . The single biggest difference between Java and C/C++ is that Java has a pointer model that eliminates the possibility of overwriting memory and corrupting data.

The Java compiler detects many problems that in other languages would show up only at runtime. As for the second point, anyone who has spent hours chasing memory corruption caused by a pointer bug will be very happy with this aspect of Java.

1.2.5 Secure

Java is intended to be used in networked/distributed environments. Toward that end, a lot of emphasis has been placed on security. Java enables the construction of virus-free, tamper-free systems.

From the beginning, Java was designed to make certain kinds of attacks impossible, among them:

• Overrunning the runtime stack—a common attack of worms and viruses

• Corrupting memory outside its own process space

• Reading or writing files without permission

Originally, the Java attitude towards downloaded code was “Bring it on!” Untrusted code was executed in a sandbox environment where it could not impact the host system. Users were assured that nothing bad could happen because Java code, no matter where it came from, was incapable of escaping from the sandbox.

However, the security model of Java is complex. Not long after the first version of the Java Development Kit was shipped, a group of security experts at Princeton University found subtle bugs that allowed untrusted code to attack the host system.

Initially, security bugs were fixed quickly. Unfortunately, over time, hackers got quite good at spotting subtle flaws in the implementation of the security architecture. Sun, and then Oracle, had a tough time keeping up with bug fixes.

After a number of high-profile attacks, browser vendors and Oracle became increasingly cautious. Java browser plug-ins no longer trust remote code unless it is digitally signed and users have agreed to its execution.

![]() Note

Note

Even though in hindsight, the Java security model was not as successful as originally envisioned, Java was well ahead of its time. A competing code delivery mechanism from Microsoft relied on digital signatures alone for security. Clearly this was not sufficient—as any user of Microsoft’s own products can confirm, programs from well-known vendors do crash and create damage.

1.2.6 Architecture-Neutral

The compiler generates an architecture-neutral object file format—the compiled code is executable on many processors, given the presence of the Java runtime system. The Java compiler does this by generating bytecode instructions which have nothing to do with a particular computer architecture. Rather, they are designed to be both easy to interpret on any machine and easily translated into native machine code on the fly.

Generating code for a “virtual machine” was not a new idea at the time. Programming languages such as Lisp, Smalltalk, and Pascal had employed this technique for many years.

Of course, interpreting virtual machine instructions is slower than running machine instructions at full speed. However, virtual machines have the option of translating the most frequently executed bytecode sequences into machine code—a process called just-in-time compilation.

Java’s virtual machine has another advantage. It increases security because it can check the behavior of instruction sequences.

1.2.7 Portable

Unlike C and C++, there are no “implementation-dependent” aspects of the specification. The sizes of the primitive data types are specified, as is the behavior of arithmetic on them.

For example, an int in Java is always a 32-bit integer. In C/C++, int can mean a 16-bit integer, a 32-bit integer, or any other size that the compiler vendor likes. The only restriction is that the int type must have at least as many bytes as a short int and cannot have more bytes than a long int. Having a fixed size for number types eliminates a major porting headache. Binary data is stored and transmitted in a fixed format, eliminating confusion about byte ordering. Strings are saved in a standard Unicode format.

The libraries that are a part of the system define portable interfaces. For example, there is an abstract Window class and implementations of it for UNIX, Windows, and the Macintosh.

The example of a Window class was perhaps poorly chosen. As anyone who has ever tried knows, it is an effort of heroic proportions to implement a user interface that looks good on Windows, the Macintosh, and ten flavors of UNIX. Java 1.0 made the heroic effort, delivering a simple toolkit that provided common user interface elements on a number of platforms. Unfortunately, the result was a library that, with a lot of work, could give barely acceptable results on different systems. That initial user interface toolkit has since been replaced, and replaced again, and portability across platforms remains an issue.

However, for everything that isn’t related to user interfaces, the Java libraries do a great job of letting you work in a platform-independent manner. You can work with files, regular expressions, XML, dates and times, databases, network connections, threads, and so on, without worrying about the underlying operating system. Not only are your programs portable, but the Java APIs are often of higher quality than the native ones.

1.2.8 Interpreted

The Java interpreter can execute Java bytecodes directly on any machine to which the interpreter has been ported. Since linking is a more incremental and lightweight process, the development process can be much more rapid and exploratory.

This seems a real stretch. Anyone who has used Lisp, Smalltalk, Visual Basic, Python, R, or Scala knows what a “rapid and exploratory” development process is. You try out something, and you instantly see the result. Java development environments are not focused on that experience.

1.2.9 High-Performance

While the performance of interpreted bytecodes is usually more than adequate, there are situations where higher performance is required. The bytecodes can be translated on the fly (at runtime) into machine code for the particular CPU the application is running on.

In the early years of Java, many users disagreed with the statement that the performance was “more than adequate.” Today, however, the just-in-time compilers have become so good that they are competitive with traditional compilers and, in some cases, even outperform them because they have more information available. For example, a just-in-time compiler can monitor which code is executed frequently and optimize just that code for speed. A more sophisticated optimization is the elimination (or “inlining”) of function calls. The just-in-time compiler knows which classes have been loaded. It can use inlining when, based upon the currently loaded collection of classes, a particular function is never overridden, and it can undo that optimization later if necessary.

1.2.10 Multithreaded

[The] benefits of multithreading are better interactive responsiveness and real-time behavior.

Nowadays, we care about concurrency because Moore’s law is coming to an end. Instead of faster processors, we just get more of them, and we have to keep them busy. Yet when you look at most programming languages, they show a shocking disregard for this problem.

Java was well ahead of its time. It was the first mainstream language to support concurrent programming. As you can see from the white paper, its motivation was a little different. At the time, multicore processors were exotic, but web programming had just started, and processors spent a lot of time waiting for a response from the server. Concurrent programming was needed to make sure the user interface didn’t freeze.

Concurrent programming is never easy, but Java has done a very good job making it manageable.

1.2.11 Dynamic

In a number of ways, Java is a more dynamic language than C or C++. It was designed to adapt to an evolving environment. Libraries can freely add new methods and instance variables without any effect on their clients. In Java, finding out runtime type information is straightforward.

This is an important feature in the situations where code needs to be added to a running program. A prime example is code that is downloaded from the Internet to run in a browser. In C or C++, this is indeed a major challenge, but the Java designers were well aware of dynamic languages that made it easy to evolve a running program. Their achievement was to bring this feature to a mainstream programming language.

![]() Note

Note

Shortly after the initial success of Java, Microsoft released a product called J++ with a programming language and virtual machine that were almost identical to Java. At this point, Microsoft is no longer supporting J++ and has instead introduced another language called C# that also has many similarities with Java but runs on a different virtual machine. This book does not cover J++ or C#.

1.3 Java Applets and the Internet

The idea here is simple: Users will download Java bytecodes from the Internet and run them on their own machines. Java programs that work on web pages are called applets. To use an applet, you only need a Java-enabled web browser, which will execute the bytecodes for you. You need not install any software. You get the latest version of the program whenever you visit the web page containing the applet. Most importantly, thanks to the security of the virtual machine, you never need to worry about attacks from hostile code.

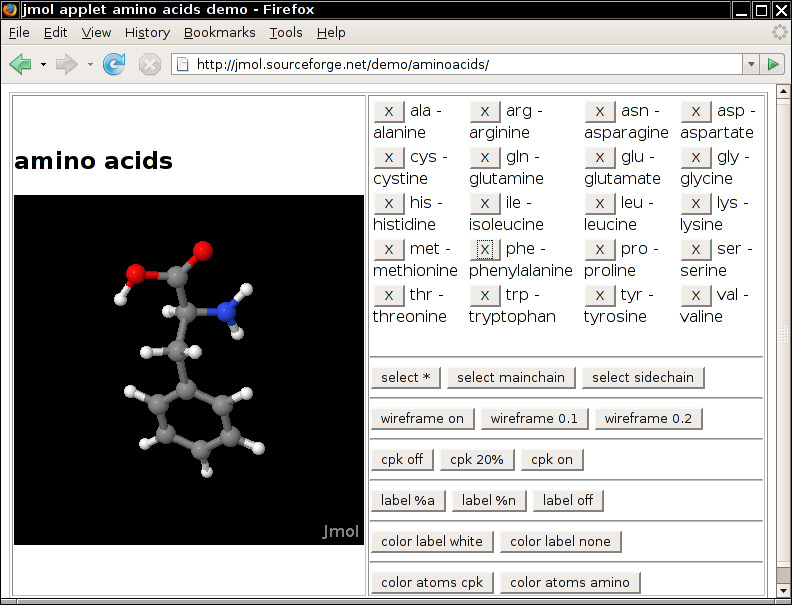

Inserting an applet into a web page works much like embedding an image. The applet becomes a part of the page, and the text flows around the space used for the applet. The point is, this image is alive. It reacts to user commands, changes its appearance, and exchanges data between the computer presenting the applet and the computer serving it.

Figure 1.1 shows a good example of a dynamic web page that carries out sophisticated calculations. The Jmol applet displays molecular structures. By using the mouse, you can rotate and zoom each molecule to better understand its structure. This kind of direct manipulation is not achievable with static web pages, but applets make it possible. (You can find this applet at http://jmol.sourceforge.net.)

When applets first appeared, they created a huge amount of excitement. Many people believe that the lure of applets was responsible for the astonishing popularity of Java. However, the initial excitement soon turned into frustration. Various versions of the Netscape and Internet Explorer browsers ran different versions of Java, some of which were seriously outdated. This sorry situation made it increasingly difficult to develop applets that took advantage of the most current Java version. Instead, Adobe’s Flash technology became popular for achieving dynamic effects in the browser. Later, when Java was dogged by serious security issues, browsers and the Java browser plug-in became increasingly restrictive. Nowadays, it requires skill and dedication to get applets to work in your browser. For example, if you visit the Jmol web site, you will likely encounter a message exhorting you to configure your browser for allowing applets to run.

1.4 A Short History of Java

This section gives a short history of Java’s evolution. It is based on various published sources (most importantly an interview with Java’s creators in the July 1995 issue of SunWorld’s online magazine).

Java goes back to 1991, when a group of Sun engineers, led by Patrick Naughton and James Gosling (a Sun Fellow and an all-around computer wizard), wanted to design a small computer language that could be used for consumer devices like cable TV switchboxes. Since these devices do not have a lot of power or memory, the language had to be small and generate very tight code. Also, as different manufacturers may choose different central processing units (CPUs), it was important that the language not be tied to any single architecture. The project was code-named “Green.”

The requirements for small, tight, and platform-neutral code led the team to design a portable language that generated intermediate code for a virtual machine.

The Sun people came from a UNIX background, so they based their language on C++ rather than Lisp, Smalltalk, or Pascal. But, as Gosling says in the interview, “All along, the language was a tool, not the end.” Gosling decided to call his language “Oak” (presumably because he liked the look of an oak tree that was right outside his window at Sun). The people at Sun later realized that Oak was the name of an existing computer language, so they changed the name to Java. This turned out to be an inspired choice.

In 1992, the Green project delivered its first product, called “*7.” It was an extremely intelligent remote control. Unfortunately, no one was interested in producing this at Sun, and the Green people had to find other ways to market their technology. However, none of the standard consumer electronics companies were interested either. The group then bid on a project to design a cable TV box that could deal with emerging cable services such as video-on-demand. They did not get the contract. (Amusingly, the company that did was led by the same Jim Clark who started Netscape—a company that did much to make Java successful.)

The Green project (with a new name of “First Person, Inc.”) spent all of 1993 and half of 1994 looking for people to buy its technology. No one was found. (Patrick Naughton, one of the founders of the group and the person who ended up doing most of the marketing, claims to have accumulated 300,000 air miles in trying to sell the technology.) First Person was dissolved in 1994.

While all of this was going on at Sun, the World Wide Web part of the Internet was growing bigger and bigger. The key to the World Wide Web was the browser translating hypertext pages to the screen. In 1994, most people were using Mosaic, a noncommercial web browser that came out of the supercomputing center at the University of Illinois in 1993. (Mosaic was partially written by Marc Andreessen as an undergraduate student on a work-study project, for $6.85 an hour. He moved on to fame and fortune as one of the cofounders and the chief of technology at Netscape.)

In the SunWorld interview, Gosling says that in mid-1994, the language developers realized that “We could build a real cool browser. It was one of the few things in the client/server mainstream that needed some of the weird things we’d done: architecture-neutral, real-time, reliable, secure—issues that weren’t terribly important in the workstation world. So we built a browser.”

The actual browser was built by Patrick Naughton and Jonathan Payne and evolved into the HotJava browser, which was designed to show off the power of Java. The builders made the browser capable of executing Java code inside web pages. This “proof of technology” was shown at SunWorld ‘95 on May 23, 1995, and inspired the Java craze that continues today.

Sun released the first version of Java in early 1996. People quickly realized that Java 1.0 was not going to cut it for serious application development. Sure, you could use Java 1.0 to make a nervous text applet that moved text randomly around in a canvas. But you couldn’t even print in Java 1.0. To be blunt, Java 1.0 was not ready for prime time. Its successor, version 1.1, filled in the most obvious gaps, greatly improved the reflection capability, and added a new event model for GUI programming. It was still rather limited, though.

The big news of the 1998 JavaOne conference was the upcoming release of Java 1.2, which replaced the early toylike GUI and graphics toolkits with sophisticated scalable versions and came a lot closer to the promise of “Write Once, Run Anywhere”™ than its predecessors. Three days after (!) its release in December 1998, Sun’s marketing department changed the name to the catchy Java 2 Standard Edition Software Development Kit Version 1.2.

Besides the Standard Edition, two other editions were introduced: the Micro Edition for embedded devices such as cell phones, and the Enterprise Edition for server-side processing. This book focuses on the Standard Edition.

Versions 1.3 and 1.4 of the Standard Edition were incremental improvements over the initial Java 2 release, with an ever-growing standard library, increased performance, and, of course, quite a few bug fixes. During this time, much of the initial hype about Java applets and client-side applications abated, but Java became the platform of choice for server-side applications.

Version 5.0 was the first release since version 1.1 that updated the Java language in significant ways. (This version was originally numbered 1.5, but the version number jumped to 5.0 at the 2004 JavaOne conference.) After many years of research, generic types (roughly comparable to C++ templates) have been added—the challenge was to add this feature without requiring changes in the virtual machine. Several other useful language features were inspired by C#: a “for each” loop, autoboxing, and annotations.

Version 6 (without the .0 suffix) was released at the end of 2006. Again, there were no language changes but additional performance improvements and library enhancements.

As datacenters increasingly relied on commodity hardware instead of specialized servers, Sun Microsystems fell on hard times and was purchased by Oracle in 2009. Development of Java stalled for a long time. In 2011, Oracle released a new version with simple enhancements as Java 7.

In 2014, the release of Java 8 followed, with the most significant changes to the Java language in almost two decades. Java 8 embraces a “functional” style of programming that makes it easy to express computations that can be executed concurrently. All programming languages must evolve to stay relevant, and Java has shown a remarkable capacity to do so.

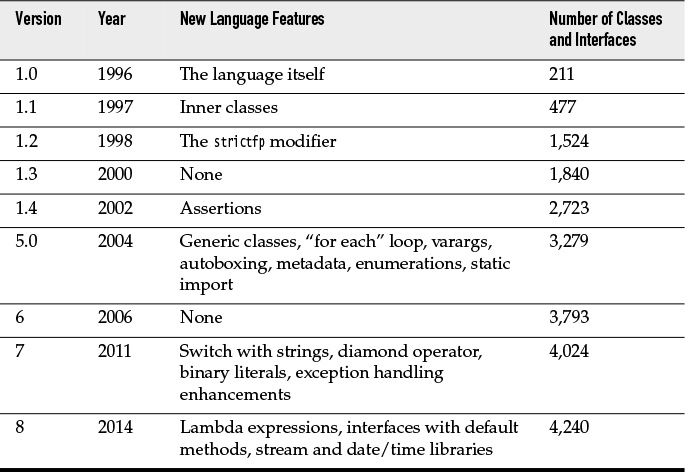

Table 1.1 shows the evolution of the Java language and library. As you can see, the size of the application programming interface (API) has grown tremendously.

1.5 Common Misconceptions about Java

This chapter closes with a commented list of some common misconceptions about Java.

Java is an extension of HTML.

Java is a programming language; HTML is a way to describe the structure of a web page. They have nothing in common except that there are HTML extensions for placing Java applets on a web page.

I use XML, so I don’t need Java.

Java is a programming language; XML is a way to describe data. You can process XML data with any programming language, but the Java API contains excellent support for XML processing. In addition, many important XML tools are implemented in Java. See Volume II for more information.

Java is an easy programming language to learn.

No programming language as powerful as Java is easy. You always have to distinguish between how easy it is to write toy programs and how hard it is to do serious work. Also, consider that only seven chapters in this book discuss the Java language. The remaining chapters of both volumes show how to put the language to work, using the Java libraries. The Java libraries contain thousands of classes and interfaces and tens of thousands of functions. Luckily, you do not need to know every one of them, but you do need to know surprisingly many to use Java for anything realistic.

Java will become a universal programming language for all platforms.

This is possible in theory. But in practice, there are domains where other languages are entrenched. Objective C and its successor, Swift, are not going to be replaced on iOS devices. Anything that happens in a browser is controlled by JavaScript. Windows programs are written in C++ or C#. Java has the edge in server-side programming and in cross-platform client applications.

Java is just another programming language.

Java is a nice programming language; most programmers prefer it to C, C++, or C#. But there have been hundreds of nice programming languages that never gained widespread popularity, whereas languages with obvious flaws, such as C++ and Visual Basic, have been wildly successful.

Why? The success of a programming language is determined far more by the utility of the support system surrounding it than by the elegance of its syntax. Are there useful, convenient, and standard libraries for the features that you need to implement? Are there tool vendors that build great programming and debugging environments? Do the language and the toolset integrate with the rest of the computing infrastructure? Java is successful because its libraries let you easily do things such as networking, web applications, and concurrency. The fact that Java reduces pointer errors is a bonus, so programmers seem to be more productive with Java—but these factors are not the source of its success.

Java is proprietary, and it should therefore be avoided.

When Java was first created, Sun gave free licenses to distributors and end users. Although Sun had ultimate control over Java, they involved many other companies in the development of language revisions and the design of new libraries. Source code for the virtual machine and the libraries has always been freely available, but only for inspection, not for modification and redistribution. Java was “closed source, but playing nice.”

This situation changed dramatically in 2007, when Sun announced that future versions of Java would be available under the General Public License (GPL), the same open source license that is used by Linux. Oracle has committed to keeping Java open source. There is only one fly in the ointment—patents. Everyone is given a patent grant to use and modify Java, subject to the GPL, but only on desktop and server platforms. If you want to use Java in embedded systems, you need a different license and will likely need to pay royalties. However, these patents will expire within the next decade, and at that point Java will be entirely free.

Java is interpreted, so it is too slow for serious applications.

In the early days of Java, the language was interpreted. Nowadays, the Java virtual machine uses a just-in-time compiler. The “hot spots” of your code will run just as fast in Java as they would in C++, and in some cases even faster.

People used to complain that Java desktop applications are slow. However, today’s computers are much faster than they were when these complaints started. A slow Java program will still run quite a bit better today than those blazingly fast C++ programs did a few years ago.

All Java programs run inside a web page.

All Java applets run inside a web browser. That is the definition of an applet—a Java program running inside a browser. But most Java programs are stand-alone applications that run outside of a web browser. In fact, many Java programs run on web servers and produce the code for web pages.

Java programs are a major security risk.

In the early days of Java, there were some well-publicized reports of failures in the Java security system. Researchers viewed it as a challenge to find chinks in the Java armor and to defy the strength and sophistication of the applet security model. The technical failures that they found have all been quickly corrected. Later, there were more serious exploits, to which Sun, and later Oracle, responded too slowly. Browser manufacturers reacted, and perhaps overreacted, by deactivating Java by default. To keep this in perspective, consider the literally millions of virus attacks in Windows executable files and Word macros that cause real grief but surprisingly little criticism of the weaknesses of the attacked platform.

Some system administrators have even deactivated Java in company browsers, while continuing to permit their users to download executable files and Word documents which pose a far greater risk. Even 20 years after its creation, Java is far safer than any other commonly available execution platform.

JavaScript is a simpler version of Java.

JavaScript, a scripting language that can be used inside web pages, was invented by Netscape and originally called LiveScript. JavaScript has a syntax that is reminiscent of Java, and the languages’ names sound similar, but otherwise they are unrelated. A subset of JavaScript is standardized as ECMA-262. JavaScript is more tightly integrated with browsers than Java applets are. In particular, a JavaScript program can modify the document that is being displayed, whereas an applet can only control the appearance of a limited area.

With Java, I can replace my desktop computer with a cheap “Internet appliance.”

When Java was first released, some people bet big that this was going to happen. Companies produced prototypes of Java-powered network computers, but users were not ready to give up a powerful and convenient desktop for a limited machine with no local storage. Nowadays, of course, the world has changed, and for a large majority of end users, the platform that matters is a mobile phone or tablet. The majority of these devices are controlled by the Android platform, which is a derivative of Java. Learning Java programming will help you with Android programming as well.