Chapter 5. Inheritance

In this chapter

• 5.1 Classes, Superclasses, and Subclasses

• 5.2 Object: The Cosmic Superclass

• 5.4 Object Wrappers and Autoboxing

• 5.5 Methods with a Variable Number of Parameters

• 5.8 Design Hints for Inheritance

Chapter 4 introduced you to classes and objects. In this chapter, you will learn about inheritance, another fundamental concept of object-oriented programming. The idea behind inheritance is that you can create new classes that are built on existing classes. When you inherit from an existing class, you reuse (or inherit) its methods, and you can add new methods and fields to adapt your new class to new situations. This technique is essential in Java programming.

This chapter also covers reflection, the ability to find out more about classes and their properties in a running program. Reflection is a powerful feature, but it is undeniably complex. Since reflection is of greater interest to tool builders than to application programmers, you can probably glance over that part of the chapter upon first reading and come back to it later.

5.1 Classes, Superclasses, and Subclasses

Let’s return to the Employee class that we discussed in the previous chapter. Suppose (alas) you work for a company where managers are treated differently from other employees. Managers are, of course, just like employees in many respects. Both employees and managers are paid a salary. However, while employees are expected to complete their assigned tasks in return for receiving their salary, managers get bonuses if they actually achieve what they are supposed to do. This is the kind of situation that cries out for inheritance. Why? Well, you need to define a new class, Manager, and add functionality. But you can retain some of what you have already programmed in the Employee class, and all the fields of the original class can be preserved. More abstractly, there is an obvious “is–a” relationship between Manager and Employee. Every manager is an employee: This “is–a” relationship is the hallmark of inheritance.

![]() Note

Note

In this chapter, we use the classic example of employees and managers, but we must ask you to take this example with a grain of salt. In the real world, an employee can become a manager, so you would want to model being a manager as a role of an employee, not a subclass. In our example, however, we assume the corporate world is populated by two kinds of people: those who are forever employees, and those who have always been managers.

5.1.1 Defining Subclasses

Here is how you define a Manager class that inherits from the Employee class. Use the Java keyword extends to denote inheritance.

public class Manager extends Employee

{

added methods and fields

}

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

Inheritance is similar in Java and C++. Java uses the extends keyword instead of the : token. All inheritance in Java is public inheritance; there is no analog to the C++ features of private and protected inheritance.

The keyword extends indicates that you are making a new class that derives from an existing class. The existing class is called the superclass, base class, or parent class. The new class is called the subclass, derived class, or child class. The terms superclass and subclass are those most commonly used by Java programmers, although some programmers prefer the parent/child analogy, which also ties in nicely with the “inheritance” theme.

The Employee class is a superclass, but not because it is superior to its subclass or contains more functionality. In fact, the opposite is true: Subclasses have more functionality than their superclasses. For example, as you will see when we go over the rest of the Manager class code, the Manager class encapsulates more data and has more functionality than its superclass Employee.

![]() Note

Note

The prefixes super and sub come from the language of sets used in theoretical computer science and mathematics. The set of all employees contains the set of all managers, and thus is said to be a superset of the set of managers. Or, to put it another way, the set of all managers is a subset of the set of all employees.

Our Manager class has a new field to store the bonus, and a new method to set it:

public class Manager extends Employee

{

private double bonus;

...

public void setBonus(double bonus)

{

this.bonus = bonus;

}

}

There is nothing special about these methods and fields. If you have a Manager object, you can simply apply the setBonus method.

Manager boss = . . .;

boss.setBonus(5000);

Of course, if you have an Employee object, you cannot apply the setBonus method—it is not among the methods defined in the Employee class.

However, you can use methods such as getName and getHireDay with Manager objects. Even though these methods are not explicitly defined in the Manager class, they are automatically inherited from the Employee superclass.

Similarly, the fields name, salary, and hireDay are taken from the superclass. Every Manager object has four fields: name, salary, hireDay, and bonus.

When defining a subclass by extending its superclass, you only need to indicate the differences between the subclass and the superclass. When designing classes, you place the most general methods in the superclass and more specialized methods in its subclasses. Factoring out common functionality by moving it to a superclass is common in object-oriented programming.

5.1.2 Overriding Methods

Some of the superclass methods are not appropriate for the Manager subclass. In particular, the getSalary method should return the sum of the base salary and the bonus. You need to supply a new method to override the superclass method:

public class Manager extends Employee

{

...

public double getSalary()

{

...

}

...

}

How can you implement this method? At first glance, it appears to be simple—just return the sum of the salary and bonus fields:

public double getSalary()

{

return salary + bonus; // won't work

}

However, that won’t work. Recall that only the Employee methods have direct access to the private fields of the Employee class. This means that the getSalary method of the Manager class cannot directly access the salary field. If the Manager methods want to access those private fields, they have to do what every other method does—use the public interface, in this case the public getSalary method of the Employee class.

So, let’s try again. You need to call getSalary instead of simply accessing the salary field:

public double getSalary()

{

double baseSalary = getSalary(); // still won't work

return baseSalary + bonus;

}

The problem is that the call to getSalary simply calls itself, because the Manager class has a getSalary method (namely, the method we are trying to implement). The consequence is an infinite chain of calls to the same method, leading to a program crash.

We need to indicate that we want to call the getSalary method of the Employee superclass, not the current class. You use the special keyword super for this purpose. The call

super.getSalary()

calls the getSalary method of the Employee class. Here is the correct version of the getSalary method for the Manager class:

public double getSalary()

{

double baseSalary = super.getSalary();

return baseSalary + bonus;

}

![]() Note

Note

Some people think of super as being analogous to the this reference. However, that analogy is not quite accurate: super is not a reference to an object. For example, you cannot assign the value super to another object variable. Instead, super is a special keyword that directs the compiler to invoke the superclass method.

As you saw, a subclass can add fields, and it can add methods or override the methods of the superclass. However, inheritance can never take away any fields or methods.

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

Java uses the keyword super to call a superclass method. In C++, you would use the name of the superclass with the :: operator instead. For example, the getSalary method of the Manager class would call Employee::getSalary instead of super.getSalary.

5.1.3 Subclass Constructors

To complete our example, let us supply a constructor.

public Manager(String name, double salary, int year, int month, int day)

{

super(name, salary, year, month, day);

bonus = 0;

}

Here, the keyword super has a different meaning. The instruction

super(n, s, year, month, day);

is shorthand for “call the constructor of the Employee superclass with n, s, year, month, and day as parameters.”

Since the Manager constructor cannot access the private fields of the Employee class, it must initialize them through a constructor. The constructor is invoked with the special super syntax. The call using super must be the first statement in the constructor for the subclass.

If the subclass constructor does not call a superclass constructor explicitly, the no-argument constructor of the superclass is invoked. If the superclass does not have a no-argument constructor and the subclass constructor does not call another superclass constructor explicitly, the Java compiler reports an error.

![]() Note

Note

Recall that the this keyword has two meanings: to denote a reference to the implicit parameter and to call another constructor of the same class. Likewise, the super keyword has two meanings: to invoke a superclass method and to invoke a superclass constructor. When used to invoke constructors, the this and super keywords are closely related. The constructor calls can only occur as the first statement in another constructor. The constructor parameters are either passed to another constructor of the same class (this) or a constructor of the superclass (super).

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

In a C++ constructor, you do not call super, but you use the initializer list syntax to construct the superclass. The Manager constructor looks like this in C++:

Manager::Manager(String name, double salary, int year, int month, int day) // C++

: Employee(name, salary, year, month, day)

{

bonus = 0;

}

After you redefine the getSalary method for Manager objects, managers will automatically have the bonus added to their salaries.

Here’s an example of this at work. We make a new manager and set the manager’s bonus:

Manager boss = new Manager("Carl Cracker", 80000, 1987, 12, 15);

boss.setBonus(5000);

We make an array of three employees:

Employee[] staff = new Employee[3];

We populate the array with a mix of managers and employees:

staff[0] = boss;

staff[1] = new Employee("Harry Hacker", 50000, 1989, 10, 1);

staff[2] = new Employee("Tony Tester", 40000, 1990, 3, 15);

We print out everyone’s salary:

for (Employee e : staff)

System.out.println(e.getName() + " " + e.getSalary());

This loop prints the following data:

Carl Cracker 85000.0

Harry Hacker 50000.0

Tommy Tester 40000.0

Now staff[1] and staff[2] each print their base salary because they are Employee objects. However, staff[0] is a Manager object whose getSalary method adds the bonus to the base salary.

What is remarkable is that the call

e.getSalary()

picks out the correct getSalary method. Note that the declared type of e is Employee, but the actual type of the object to which e refers can be either Employee or Manager.

When e refers to an Employee object, the call e.getSalary() calls the getSalary method of the Employee class. However, when e refers to a Manager object, then the getSalary method of the Manager class is called instead. The virtual machine knows about the actual type of the object to which e refers, and therefore can invoke the correct method.

The fact that an object variable (such as the variable e) can refer to multiple actual types is called polymorphism. Automatically selecting the appropriate method at runtime is called dynamic binding. We discuss both topics in more detail in this chapter.

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

In C++, you need to declare a member function as virtual if you want dynamic binding. In Java, dynamic binding is the default behavior; if you do not want a method to be virtual, you tag it as final. (We discuss the final keyword later in this chapter.)

Listing 5.1 contains a program that shows how the salary computation differs for Employee (Listing 5.2) and Manager (Listing 5.3) objects.

Listing 5.1 inheritance/ManagerTest.java

1 package inheritance;

2

3 /**

4 * This program demonstrates inheritance.

5 * @version 1.21 2004-02-21

6 * @author Cay Horstmann

7 */

8 public class ManagerTest

9 {

10 public static void main(String[] args)

11 {

12 // construct a Manager object

13 Manager boss = new Manager("Carl Cracker", 80000, 1987, 12, 15);

14 boss.setBonus(5000);

15

16 Employee[] staff = new Employee[3];

17

18 // fill the staff array with Manager and Employee objects

19

20 staff[0] = boss;

21 staff[1] = new Employee("Harry Hacker", 50000, 1989, 10, 1);

22 staff[2] = new Employee("Tommy Tester", 40000, 1990, 3, 15);

23

24 // print out information about all Employee objects

25 for (Employee e : staff)

26 System.out.println("name=" + e.getName() + ",salary=" + e.getSalary());

27 }

28 }

Listing 5.2 inheritance/Employee.java

1 package inheritance;

2

3 import java.time.*;

4

5 public class Employee

6 {

7 private String name;

8 private double salary;

9 private LocalDate hireDay;

10

11 public Employee(String name, double salary, int year, int month, int day)

12 {

13 this.name = name;

14 this.salary = salary;

15 hireDay = LocalDate.of(year, month, day);

16 }

17

18 public String getName()

19 {

20 return name;

21 }

22

23 public double getSalary()

24 {

25 return salary;

26 }

27

28 public LocalDate getHireDay()

29 {

30 return hireDay;

31 }

32

33 public void raiseSalary(double byPercent)

34 {

35 double raise = salary * byPercent / 100;

36 salary += raise;

37 }

38 }

Listing 5.3 inheritance/Manager.java

1 package inheritance;

2

3 public class Manager extends Employee

4 {

5 private double bonus;

6

7 /**

8 * @param name the employee's name

9 * @param salary the salary

10 * @param year the hire year

11 * @param month the hire month

12 * @param day the hire day

13 */

14 public Manager(String name, double salary, int year, int month, int day)

15 {

16 super(name, salary, year, month, day);

17 bonus = 0;

18 }

19

20 public double getSalary()

21 {

22 double baseSalary = super.getSalary();

23 return baseSalary + bonus;

24 }

25

26 public void setBonus(double b)

27 {

28 bonus = b;

29 }

30 }

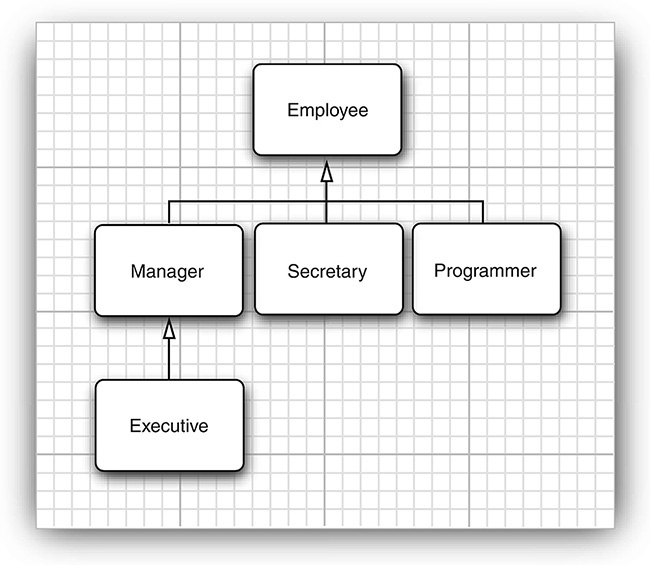

5.1.4 Inheritance Hierarchies

Inheritance need not stop at deriving one layer of classes. We could have an Executive class that extends Manager, for example. The collection of all classes extending a common superclass is called an inheritance hierarchy, as shown in Figure 5.1. The path from a particular class to its ancestors in the inheritance hierarchy is its inheritance chain.

There is usually more than one chain of descent from a distant ancestor class. You could form subclasses Programmer or Secretary that extend Employee, and they would have nothing to do with the Manager class (or with each other). This process can continue as long as is necessary.

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

In C++, a class can have multiple superclasses. Java does not support multiple inheritance. For ways to recover much of the functionality of multiple inheritance, see Section 6.1, “Interfaces,” on p. 288.

5.1.5 Polymorphism

A simple rule can help you decide whether or not inheritance is the right design for your data. The “is–a” rule states that every object of the subclass is an object of the superclass. For example, every manager is an employee. Thus, it makes sense for the Manager class to be a subclass of the Employee class. Naturally, the opposite is not true—not every employee is a manager.

Another way of formulating the “is–a” rule is the substitution principle. That principle states that you can use a subclass object whenever the program expects a superclass object.

For example, you can assign a subclass object to a superclass variable.

Employee e;

e = new Employee(. . .); // Employee object expected

e = new Manager(. . .); // OK, Manager can be used as well

In the Java programming language, object variables are polymorphic. A variable of type Employee can refer to an object of type Employee or to an object of any subclass of the Employee class (such as Manager, Executive, Secretary, and so on).

We took advantage of this principle in Listing 5.1:

Manager boss = new Manager(. . .);

Employee[] staff = new Employee[3];

staff[0] = boss;

In this case, the variables staff[0] and boss refer to the same object. However, staff[0] is considered to be only an Employee object by the compiler.

That means you can call

boss.setBonus(5000); // OK

but you can’t call

staff[0].setBonus(5000); // Error

The declared type of staff[0] is Employee, and the setBonus method is not a method of the Employee class.

However, you cannot assign a superclass reference to a subclass variable. For example, it is not legal to make the assignment

Manager m = staff[i]; // Error

The reason is clear: Not all employees are managers. If this assignment were to succeed and m were to refer to an Employee object that is not a manager, then it would later be possible to call m.setBonus(...) and a runtime error would occur.

![]() Caution

Caution

In Java, arrays of subclass references can be converted to arrays of superclass references without a cast. For example, consider this array of managers:

Manager[] managers = new Manager[10];

It is legal to convert this array to an Employee[] array:

Employee[] staff = managers; // OK

Sure, why not, you may think. After all, if managers[i] is a Manager, it is also an Employee. But actually, something surprising is going on. Keep in mind that managers and staff are references to the same array. Now consider the statement

staff[0] = new Employee("Harry Hacker", ...);

The compiler will cheerfully allow this assignment. But staff[0] and managers[0] are the same reference, so it looks as if we managed to smuggle a mere employee into the management ranks. That would be very bad—calling managers[0].setBonus(1000) would try to access a nonexistent instance field and would corrupt neighboring memory.

To make sure no such corruption can occur, all arrays remember the element type with which they were created, and they monitor that only compatible references are stored into them. For example, the array created as new Manager[10] remembers that it is an array of managers. Attempting to store an Employee reference causes an ArrayStoreException.

5.1.6 Understanding Method Calls

It is important to understand exactly how a method call is applied to an object. Let’s say we call x.f(args), and the implicit parameter x is declared to be an object of class C. Here is what happens:

1. The compiler looks at the declared type of the object and the method name. Note that there may be multiple methods, all with the same name, f, but with different parameter types. For example, there may be a method f(int) and a method f(String). The compiler enumerates all methods called f in the class C and all accessible methods called f in the superclasses of C. (Private methods of the superclass are not accessible.)

Now the compiler knows all possible candidates for the method to be called.

2. Next, the compiler determines the types of the arguments that are supplied in the method call. If among all the methods called f there is a unique method whose parameter types are a best match for the supplied arguments, that method is chosen to be called. This process is called overloading resolution. For example, in a call x.f("Hello"), the compiler picks f(String) and not f(int). The situation can get complex because of type conversions (int to double, Manager to Employee, and so on). If the compiler cannot find any method with matching parameter types or if multiple methods all match after applying conversions, the compiler reports an error.

Now the compiler knows the name and parameter types of the method that needs to be called.

![]() Note

Note

Recall that the name and parameter type list for a method is called the method’s signature. For example, f(int) and f(String) are two methods with the same name but different signatures. If you define a method in a subclass that has the same signature as a superclass method, you override the superclass method.

The return type is not part of the signature. However, when you override a method, you need to keep the return type compatible. A subclass may change the return type to a subtype of the original type. For example, suppose the Employee class has a method

public Employee getBuddy() { ... }

A manager would never want to have a lowly employee as a buddy. To reflect that fact, the Manager subclass can override this method as

public Manager getBuddy() { ... } // OK to change return type

We say that the two getBuddy methods have covariant return types.

3. If the method is private, static, final, or a constructor, then the compiler knows exactly which method to call. (The final modifier is explained in the next section.) This is called static binding. Otherwise, the method to be called depends on the actual type of the implicit parameter, and dynamic binding must be used at runtime. In our example, the compiler would generate an instruction to call f(String) with dynamic binding.

4. When the program runs and uses dynamic binding to call a method, the virtual machine must call the version of the method that is appropriate for the actual type of the object to which x refers. Let’s say the actual type is D, a subclass of C. If the class D defines a method f(String), that method is called. If not, D’s superclass is searched for a method f(String), and so on.

It would be time consuming to carry out this search every time a method is called. Therefore, the virtual machine precomputes for each class a method table that lists all method signatures and the actual methods to be called. When a method is actually called, the virtual machine simply makes a table lookup. In our example, the virtual machine consults the method table for the class D and looks up the method to call for f(String). That method may be D.f(String) or X.f(String), where X is some superclass of D. There is one twist to this scenario. If the call is super.f(param), then the compiler consults the method table of the superclass of the implicit parameter.

Let’s look at this process in detail in the call e.getSalary() in Listing 5.1. The declared type of e is Employee. The Employee class has a single method, called getSalary, with no method parameters. Therefore, in this case, we don’t worry about overloading resolution.

The getSalary method is not private, static, or final, so it is dynamically bound. The virtual machine produces method tables for the Employee and Manager classes. The Employee table shows that all methods are defined in the Employee class itself:

Employee:

getName() -> Employee.getName()

getSalary() -> Employee.getSalary()

getHireDay() -> Employee.getHireDay()

raiseSalary(double) -> Employee.raiseSalary(double)

Actually, that isn’t the whole story—as you will see later in this chapter, the Employee class has a superclass Object from which it inherits a number of methods. We ignore the Object methods for now.

The Manager method table is slightly different. Three methods are inherited, one method is redefined, and one method is added.

Manager:

getName() -> Employee.getName()

getSalary() -> Manager.getSalary()

getHireDay() -> Employee.getHireDay()

raiseSalary(double) -> Employee.raiseSalary(double)

setBonus(double) -> Manager.setBonus(double)

At runtime, the call e.getSalary() is resolved as follows:

1. First, the virtual machine fetches the method table for the actual type of e. That may be the table for Employee, Manager, or another subclass of Employee.

2. Then, the virtual machine looks up the defining class for the getSalary() signature. Now it knows which method to call.

3. Finally, the virtual machine calls the method.

Dynamic binding has a very important property: It makes programs extensible without the need for modifying existing code. Suppose a new class Executive is added and there is the possibility that the variable e refers to an object of that class. The code containing the call e.getSalary() need not be recompiled. The Executive.getSalary() method is called automatically if e happens to refer to an object of type Executive.

![]() Caution

Caution

When you override a method, the subclass method must be at least as visible as the superclass method. In particular, if the superclass method is public, the subclass method must also be declared public. It is a common error to accidentally omit the public specifier for the subclass method. The compiler then complains that you try to supply a more restrictive access privilege.

5.1.7 Preventing Inheritance: Final Classes and Methods

Occasionally, you want to prevent someone from forming a subclass from one of your classes. Classes that cannot be extended are called final classes, and you use the final modifier in the definition of the class to indicate this. For example, suppose we want to prevent others from subclassing the Executive class. Simply declare the class using the final modifier, as follows:

public final class Executive extends Manager

{

...

}

You can also make a specific method in a class final. If you do this, then no subclass can override that method. (All methods in a final class are automatically final.) For example:

public class Employee

{

...

public final String getName()

{

return name;

}

...

}

![]() Note

Note

Recall that fields can also be declared as final. A final field cannot be changed after the object has been constructed. However, if a class is declared final, only the methods, not the fields, are automatically final.

There is only one good reason to make a method or class final: to make sure its semantics cannot be changed in a subclass. For example, the getTime and setTime methods of the Calendar class are final. This indicates that the designers of the Calendar class have taken over responsibility for the conversion between the Date class and the calendar state. No subclass should be allowed to mess up this arrangement. Similarly, the String class is a final class. That means nobody can define a subclass of String. In other words, if you have a String reference, you know it refers to a String and nothing but a String.

Some programmers believe that you should declare all methods as final unless you have a good reason to want polymorphism. In fact, in C++ and C#, methods do not use polymorphism unless you specifically request it. That may be a bit extreme, but we agree that it is a good idea to think carefully about final methods and classes when you design a class hierarchy.

In the early days of Java, some programmers used the final keyword hoping to avoid the overhead of dynamic binding. If a method is not overridden, and it is short, then a compiler can optimize the method call away—a process called inlining. For example, inlining the call e.getName() replaces it with the field access e.name. This is a worthwhile improvement—CPUs hate branching because it interferes with their strategy of prefetching instructions while processing the current one. However, if getName can be overridden in another class, then the compiler cannot inline it because it has no way of knowing what the overriding code may do.

Fortunately, the just-in-time compiler in the virtual machine can do a better job than a traditional compiler. It knows exactly which classes extend a given class, and it can check whether any class actually overrides a given method. If a method is short, frequently called, and not actually overridden, the just-in-time compiler can inline the method. What happens if the virtual machine loads another subclass that overrides an inlined method? Then the optimizer must undo the inlining. That takes time, but it happens rarely.

5.1.8 Casting

Recall from Chapter 3 that the process of forcing a conversion from one type to another is called casting. The Java programming language has a special notation for casts. For example,

double x = 3.405;

int nx = (int) x;

converts the value of the expression x into an integer, discarding the fractional part.

Just as you occasionally need to convert a floating-point number to an integer, you may need to convert an object reference from one class to another. To actually make a cast of an object reference, use a syntax similar to what you use for casting a numeric expression. Surround the target class name with parentheses and place it before the object reference you want to cast. For example:

Manager boss = (Manager) staff[0];

There is only one reason why you would want to make a cast—to use an object in its full capacity after its actual type has been temporarily forgotten. For example, in the ManagerTest class, the staff array had to be an array of Employee objects because some of its elements were regular employees. We would need to cast the managerial elements of the array back to Manager to access any of its new variables. (Note that in the sample code for the first section, we made a special effort to avoid the cast. We initialized the boss variable with a Manager object before storing it in the array. We needed the correct type to set the bonus of the manager.)

As you know, in Java every variable has a type. The type describes the kind of object the variable refers to and what it can do. For example, staff[i] refers to an Employee object (so it can also refer to a Manager object).

The compiler checks that you do not promise too much when you store a value in a variable. If you assign a subclass reference to a superclass variable, you are promising less, and the compiler will simply let you do it. If you assign a superclass reference to a subclass variable, you are promising more. Then you must use a cast so that your promise can be checked at runtime.

What happens if you try to cast down an inheritance chain and are “lying” about what an object contains?

Manager boss = (Manager) staff[1]; // Error

When the program runs, the Java runtime system notices the broken promise and generates a ClassCastException. If you do not catch the exception, your program terminates. Thus, it is good programming practice to find out whether a cast will succeed before attempting it. Simply use the instanceof operator. For example:

if (staff[1] instanceof Manager)

{

boss = (Manager) staff[1];

...

}

Finally, the compiler will not let you make a cast if there is no chance for the cast to succeed. For example, the cast

String c = (String) staff[1];

is a compile-time error because String is not a subclass of Employee.

To sum up:

• You can cast only within an inheritance hierarchy.

• Use instanceof to check before casting from a superclass to a subclass.

![]() Note

Note

The test

x instanceof C

does not generate an exception if x is null. It simply returns false. That makes sense: null refers to no object, so it certainly doesn’t refer to an object of type C.

Actually, converting the type of an object by a cast is not usually a good idea. In our example, you do not need to cast an Employee object to a Manager object for most purposes. The getSalary method will work correctly on both objects of both classes. The dynamic binding that makes polymorphism work locates the correct method automatically.

The only reason to make the cast is to use a method that is unique to managers, such as setBonus. If for some reason you find yourself wanting to call setBonus on Employee objects, ask yourself whether this is an indication of a design flaw in the superclass. It may make sense to redesign the superclass and add a setBonus method. Remember, it takes only one uncaught ClassCastException to terminate your program. In general, it is best to minimize the use of casts and the instanceof operator.

Java uses the cast syntax from the “bad old days” of C, but it works like the safe dynamic_cast operation of C++. For example,

Manager boss = (Manager) staff[1]; // Java

is the same as

Manager* boss = dynamic_cast<Manager*>(staff[1]); // C++

with one important difference. If the cast fails, it does not yield a null object but throws an exception. In this sense, it is like a C++ cast of references. This is a pain in the neck. In C++, you can take care of the type test and type conversion in one operation.

Manager* boss = dynamic_cast<Manager*>(staff[1]); // C++

if (boss != NULL) . . .

In Java, you need to use a combination of the instanceof operator and a cast.

if (staff[1] instanceof Manager)

{

Manager boss = (Manager) staff[1];

...

}

5.1.9 Abstract Classes

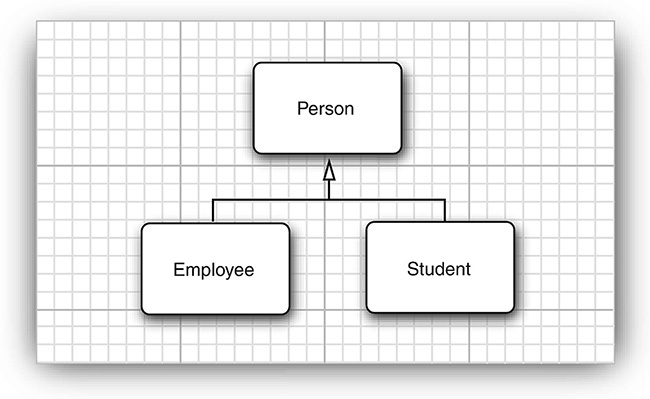

As you move up the inheritance hierarchy, classes become more general and probably more abstract. At some point, the ancestor class becomes so general that you think of it more as a basis for other classes than as a class with specific instances you want to use. Consider, for example, an extension of our Employee class hierarchy. An employee is a person, and so is a student. Let us extend our class hierarchy to include classes Person and Student. Figure 5.2 shows the inheritance relationships between these classes.

Why bother with so high a level of abstraction? There are some attributes that make sense for every person, such as name. Both students and employees have names, and introducing a common superclass lets us factor out the getName method to a higher level in the inheritance hierarchy.

Now let’s add another method, getDescription, whose purpose is to return a brief description of the person, such as

an employee with a salary of $50,000.00

a student majoring in computer science

It is easy to implement this method for the Employee and Student classes. But what information can you provide in the Person class? The Person class knows nothing about the person except the name. Of course, you could implement Person.getDescription() to return an empty string. But there is a better way. If you use the abstract keyword, you do not need to implement the method at all.

public abstract String getDescription();

// no implementation required

For added clarity, a class with one or more abstract methods must itself be declared abstract.

public abstract class Person

{ ...

public abstract String getDescription();

}

In addition to abstract methods, abstract classes can have fields and concrete methods. For example, the Person class stores the name of the person and has a concrete method that returns it.

public abstract class Person

{

private String name;

public Person(String name)

{

this.name = name;

}

public abstract String getDescription();

public String getName()

{

return name;

}

}

![]() Tip

Tip

Some programmers don’t realize that abstract classes can have concrete methods. You should always move common fields and methods (whether abstract or not) to the superclass (whether abstract or not).

Abstract methods act as placeholders for methods that are implemented in the subclasses. When you extend an abstract class, you have two choices. You can leave some or all of the abstract methods undefined; then you must tag the subclass as abstract as well. Or you can define all methods, and the subclass is no longer abstract.

For example, we will define a Student class that extends the abstract Person class and implements the getDescription method. None of the methods of the Student class are abstract, so it does not need to be declared as an abstract class.

A class can even be declared as abstract though it has no abstract methods.

Abstract classes cannot be instantiated. That is, if a class is declared as abstract, no objects of that class can be created. For example, the expression

new Person("Vince Vu")

is an error. However, you can create objects of concrete subclasses.

Note that you can still create object variables of an abstract class, but such a variable must refer to an object of a nonabstract subclass. For example:

Person p = new Student("Vince Vu", "Economics");

Here p is a variable of the abstract type Person that refers to an instance of the nonabstract subclass Student.

In C++, an abstract method is called a pure virtual function and is tagged with a trailing = 0, such as in

class Person // C++

{

public:

virtual string getDescription() = 0;

...

};

A C++ class is abstract if it has at least one pure virtual function. In C++, there is no special keyword to denote abstract classes.

Let us define a concrete subclass Student that extends the abstract class Person:

public class Student extends Person

{

private String major;

public Student(String name, String major)

{

super(name);

this.major = major;

}

public String getDescription()

{

return "a student majoring in " + major;

}

}

The Student class defines the getDescription method. Therefore, all methods in the Student class are concrete, and the class is no longer an abstract class.

The program shown in Listing 5.4 defines the abstract superclass Person (Listing 5.5) and two concrete subclasses, Employee (Listing 5.6) and Student (Listing 5.7). We fill an array of Person references with employee and student objects:

Person[] people = new Person[2];

people[0] = new Employee(. . .);

people[1] = new Student(. . .);

We then print the names and descriptions of these objects:

for (Person p : people)

System.out.println(p.getName() + ", " + p.getDescription());

Some people are baffled by the call

p.getDescription()

Isn’t this a call to an undefined method? Keep in mind that the variable p never refers to a Person object because it is impossible to construct an object of the abstract Person class. The variable p always refers to an object of a concrete subclass such as Employee or Student. For these objects, the getDescription method is defined.

Could you have omitted the abstract method altogether from the Person superclass, simply defining the getDescription methods in the Employee and Student subclasses? If you did that, you wouldn’t have been able to invoke the getDescription method on the variable p. The compiler ensures that you invoke only methods that are declared in the class.

Abstract methods are an important concept in the Java programming language. You will encounter them most commonly inside interfaces. For more information about interfaces, turn to Chapter 6.

Listing 5.4 abstractClasses/PersonTest.java

1 package abstractClasses;

2

3 /**

4 * This program demonstrates abstract classes.

5 * @version 1.01 2004-02-21

6 * @author Cay Horstmann

7 */

8 public class PersonTest

9 {

10 public static void main(String[] args)

11 {

12 Person[] people = new Person[2];

13

14 // fill the people array with Student and Employee objects

15 people[0] = new Employee("Harry Hacker", 50000, 1989, 10, 1);

16 people[1] = new Student("Maria Morris", "computer science");

17

18 // print out names and descriptions of all Person objects

19 for (Person p : people)

20 System.out.println(p.getName() + ", " + p.getDescription());

21 }

22 }

Listing 5.5 abstractClasses/Person.java

1 package abstractClasses;

2

3 public abstract class Person

4 {

5 public abstract String getDescription();

6 private String name;

7

8 public Person(String name)

9 {

10 this.name = name;

11 }

12

13 public String getName()

14 {

15 return name;

16 }

17 }

Listing 5.6 abstractClasses/Employee.java

1 package abstractClasses;

2

3 import java.time.*;

4

5 public class Employee extends Person

6 {

7 private double salary;

8 private LocalDate hireDay;

9

10 public Employee(String name, double salary, int year, int month, int day)

11 {

12 super(name);

13 this.salary = salary;

14 hireDay = LocalDate.of(year, month, day);

15 }

16

17 public double getSalary()

18 {

19 return salary;

20 }

21

22 public LocalDate getHireDay()

23 {

24 return hireDay;

25 }

26

27 public String getDescription()

28 {

29 return String.format("an employee with a salary of $%.2f", salary);

30 }

31

32 public void raiseSalary(double byPercent)

33 {

34 double raise = salary * byPercent / 100;

35 salary += raise;

36 }

37 }

Listing 5.7 abstractClasses/Student.java

1 package abstractClasses;

2

3 public class Student extends Person

4 {

5 private String major;

6

7 /**

8 * @param nama the student's name

9 * @param major the student's major

10 */

11 public Student(String name, String major)

12 {

13 // pass n to superclass constructor

14 super(name);

15 this.major = major;

16 }

17

18 public String getDescription()

19 {

20 return "a student majoring in " + major;

21 }

22 }

5.1.10 Protected Access

As you know, fields in a class are best tagged as private, and methods are usually tagged as public. Any features declared private won’t be visible to other classes. As we said at the beginning of this chapter, this is also true for subclasses: A subclass cannot access the private fields of its superclass.

There are times, however, when you want to restrict a method to subclasses only or, less commonly, to allow subclass methods to access a superclass field. In that case, you declare a class feature as protected. For example, if the superclass Employee declares the hireDay field as protected instead of private, then the Manager methods can access it directly.

However, the Manager class methods can peek inside the hireDay field of Manager objects only, not of other Employee objects. This restriction is made so that you can’t abuse the protected mechanism by forming subclasses just to gain access to the protected fields.

In practice, use protected fields with caution. Suppose your class is used by other programmers and you designed it with protected fields. Unknown to you, other programmers may inherit classes from your class and start accessing your protected fields. In this case, you can no longer change the implementation of your class without upsetting those programmers. That is against the spirit of OOP, which encourages data encapsulation.

Protected methods make more sense. A class may declare a method as protected if it is tricky to use. This indicates that the subclasses (which, presumably, know their ancestor well) can be trusted to use the method correctly, but other classes cannot.

A good example of this kind of method is the clone method of the Object class—see Chapter 6 for more details.

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

As it happens, protected features in Java are visible to all subclasses as well as to all other classes in the same package. This is slightly different from the C++ meaning of protected, and it makes the notion of protected in Java even less safe than in C++.

Here is a summary of the four access modifiers in Java that control visibility:

1. Visible to the class only (private).

2. Visible to the world (public).

3. Visible to the package and all subclasses (protected).

4. Visible to the package—the (unfortunate) default. No modifiers are needed.

5.2 Object: The Cosmic Superclass

The Object class is the ultimate ancestor—every class in Java extends Object. However, you never have to write

public class Employee extends Object

The ultimate superclass Object is taken for granted if no superclass is explicitly mentioned. Since every class in Java extends Object, it is important to be familiar with the services provided by the Object class. We go over the basic ones in this chapter; consult the later chapters or view the online documentation for what is not covered here. (Several methods of Object come up only when dealing with concurrency—see Chapter 14 for more on threads.)

You can use a variable of type Object to refer to objects of any type:

Object obj = new Employee("Harry Hacker", 35000);

Of course, a variable of type Object is only useful as a generic holder for arbitrary values. To do anything specific with the value, you need to have some knowledge about the original type and apply a cast:

Employee e = (Employee) obj;

In Java, only the values of primitive types (numbers, characters, and boolean values) are not objects.

All array types, no matter whether they are arrays of objects or arrays of primitive types, are class types that extend the Object class.

Employee[] staff = new Employee[10];

obj = staff; // OK

obj = new int[10]; // OK

![]() C++ Note

C++ Note

In C++, there is no cosmic root class. However, every pointer can be converted to a void* pointer.

5.2.1 The equals Method

The equals method in the Object class tests whether one object is considered equal to another. The equals method, as implemented in the Object class, determines whether two object references are identical. This is a pretty reasonable default—if two objects are identical, they should certainly be equal. For quite a few classes, nothing else is required. For example, it makes little sense to compare two PrintStream objects for equality. However, you will often want to implement state-based equality testing, in which two objects are considered equal when they have the same state.

For example, let us consider two employees equal if they have the same name, salary, and hire date. (In an actual employee database, it would be more sensible to compare IDs instead. We use this example to demonstrate the mechanics of implementing the equals method.)

public class Employee

{

...

public boolean equals(Object otherObject)

{

// a quick test to see if the objects are identical

if (this == otherObject) return true;

// must return false if the explicit parameter is null

if (otherObject == null) return false;

// if the classes don't match, they can't be equal

if (getClass() != otherObject.getClass())

return false;

// now we know otherObject is a non-null Employee

Employee other = (Employee) otherObject;

// test whether the fields have identical values

return name.equals(other.name)

&& salary == other.salary

&& hireDay.equals(other.hireDay);

}

}

The getClass method returns the class of an object—we discuss this method in detail later in this chapter. In our test, two objects can only be equal when they belong to the same class.

![]() Tip

Tip

To guard against the possibility that name or hireDay are null, use the Objects.equals method. The call Objects.equals(a, b) returns true if both arguments are null, false if only one is null, and calls a.equals(b) otherwise. With that method, the last statement of the Employee.equals method becomes

return Objects.equals(name, other.name)

&& salary == other.salary

&& Objects.equals(hireDay, other.hireDay);

When you define the equals method for a subclass, first call equals on the superclass. If that test doesn’t pass, then the objects can’t be equal. If the superclass fields are equal, you are ready to compare the instance fields of the subclass.

public class Manager extends Employee

{

...

public boolean equals(Object otherObject)

{

if (!super.equals(otherObject)) return false;

// super.equals checked that this and otherObject belong to the same class

Manager other = (Manager) otherObject;

return bonus == other.bonus;

}

}

5.2.2 Equality Testing and Inheritance

How should the equals method behave if the implicit and explicit parameters don’t belong to the same class? This has been an area of some controversy. In the preceding example, the equals method returns false if the classes don’t match exactly. But many programmers use an instanceof test instead:

if (!(otherObject instanceof Employee)) return false;

This leaves open the possibility that otherObject can belong to a subclass. However, this approach can get you into trouble. Here is why. The Java Language Specification requires that the equals method has the following properties:

1. It is reflexive: For any non-null reference x, x.equals(x) should return true.

2. It is symmetric: For any references x and y, x.equals(y) should return true if and only if y.equals(x) returns true.

3. It is transitive: For any references x, y, and z, if x.equals(y) returns true and y.equals(z) returns true, then x.equals(z) should return true.

4. It is consistent: If the objects to which x and y refer haven’t changed, then repeated calls to x.equals(y) return the same value.

5. For any non-null reference x, x.equals(null) should return false.

These rules are certainly reasonable. You wouldn’t want a library implementor to ponder whether to call x.equals(y) or y.equals(x) when locating an element in a data structure.

However, the symmetry rule has subtle consequences when the parameters belong to different classes. Consider a call

e.equals(m)

where e is an Employee object and m is a Manager object, both of which happen to have the same name, salary, and hire date. If Employee.equals uses an instanceof test, the call returns true. But that means that the reverse call

m.equals(e)

also needs to return true—the symmetry rule does not allow it to return false or to throw an exception.

That leaves the Manager class in a bind. Its equals method must be willing to compare itself to any Employee, without taking manager-specific information into account! All of a sudden, the instanceof test looks less attractive.

Some authors have gone on record that the getClass test is wrong because it violates the substitution principle. A commonly cited example is the equals method in the AbstractSet class that tests whether two sets have the same elements. The AbstractSet class has two concrete subclasses, TreeSet and HashSet, that use different algorithms for locating set elements. You really want to be able to compare any two sets, no matter how they are implemented.

However, the set example is rather specialized. It would make sense to declare AbstractSet.equals as final, because nobody should redefine the semantics of set equality. (The method is not actually final. This allows a subclass to implement a more efficient algorithm for the equality test.)

The way we see it, there are two distinct scenarios:

• If subclasses can have their own notion of equality, then the symmetry requirement forces you to use the getClass test.

• If the notion of equality is fixed in the superclass, then you can use the instanceof test and allow objects of different subclasses to be equal to one another.

In the example with employees and managers, we consider two objects to be equal when they have matching fields. If we have two Manager objects with the same name, salary, and hire date, but with different bonuses, we want them to be different. Therefore, we used the getClass test.

But suppose we used an employee ID for equality testing. This notion of equality makes sense for all subclasses. Then we could use the instanceof test, and we should have declared Employee.equals as final.

![]() Note

Note

The standard Java library contains over 150 implementations of equals methods, with a mishmash of using instanceof, calling getClass, catching a ClassCastException, or doing nothing at all. Check out the API documentation of the java.sql.Timestamp class, where the implementors note with some embarrassment that they have painted themselves in a corner. The Timestamp class inherits from java.util.Date, whose equals method uses an instanceof test, and it is impossible to override equals to be both symmetric and accurate.

Here is a recipe for writing the perfect equals method:

1. Name the explicit parameter otherObject—later, you will need to cast it to another variable that you should call other.

2. Test whether this happens to be identical to otherObject:

if (this == otherObject) return true;

This statement is just an optimization. In practice, this is a common case. It is much cheaper to check for identity than to compare the fields.

3. Test whether otherObject is null and return false if it is. This test is required.

if (otherObject == null) return false;

4. Compare the classes of this and otherObject. If the semantics of equals can change in subclasses, use the getClass test:

if (getClass() != otherObject.getClass()) return false;

If the same semantics holds for all subclasses, you can use an instanceof test:

if (!(otherObject instanceof ClassName)) return false;

5. Cast otherObject to a variable of your class type:

ClassName other = (ClassName) otherObject

6. Now compare the fields, as required by your notion of equality. Use == for primitive type fields, Objects.equals for object fields. Return true if all fields match, false otherwise.

return field1 == other.field1

&& Objects.equals(field2, other.field2)

&& . . .;

If you redefine equals in a subclass, include a call to super.equals(other).

![]() Tip

Tip

If you have fields of array type, you can use the static Arrays.equals method to check that the corresponding array elements are equal.

Here is a common mistake when implementing the equals method. Can you spot the problem?

public class Employee

{

public boolean equals(Employee other)

{

return other != null

&& getClass() == other.getClass()

&& Objects.equals(name, other.name)

&& salary == other.salary

&& Objects.equals(hireDay, other.hireDay);

}

...

}

This method declares the explicit parameter type as Employee. As a result, it does not override the equals method of the Object class but defines a completely unrelated method.

You can protect yourself against this type of error by tagging methods that are intended to override superclass methods with @Override:

@Override public boolean equals(Object other)

If you made a mistake and are defining a new method, the compiler reports an error. For example, suppose you add the following declaration to the Employee class:

@Override public boolean equals(Employee other)

An error is reported because this method doesn’t override any method from the Object superclass.

5.2.3 The hashCode Method

A hash code is an integer that is derived from an object. Hash codes should be scrambled—if x and y are two distinct objects, there should be a high probability that x.hashCode() and y.hashCode() are different. Table 5.1 lists a few examples of hash codes that result from the hashCode method of the String class.

The String class uses the following algorithm to compute the hash code:

int hash = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < length(); i++)

hash = 31 * hash + charAt(i);

The hashCode method is defined in the Object class. Therefore, every object has a default hash code. That hash code is derived from the object’s memory address. Consider this example:

String s = "Ok";

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder(s);

System.out.println(s.hashCode() + " " + sb.hashCode());

String t = new String("Ok");

StringBuilder tb = new StringBuilder(t);

System.out.println(t.hashCode() + " " + tb.hashCode());

Table 5.2 shows the result.

Note that the strings s and t have the same hash code because, for strings, the hash codes are derived from their contents. The string builders sb and tb have different hash codes because no hashCode method has been defined for the StringBuilder class and the default hashCode method in the Object class derives the hash code from the object’s memory address.

If you redefine the equals method, you will also need to redefine the hashCode method for objects that users might insert into a hash table. (We discuss hash tables in Chapter 9.)

The hashCode method should return an integer (which can be negative). Just combine the hash codes of the instance fields so that the hash codes for different objects are likely to be widely scattered.

For example, here is a hashCode method for the Employee class:

public class Employee

{

public int hashCode()

{

return 7 * name.hashCode()

+ 11 * new Double(salary).hashCode()

+ 13 * hireDay.hashCode();

}

...

}

However, you can do better. First, use the null-safe method Objects.hashCode. It returns 0 if its argument is null and the result of calling hashCode on the argument otherwise. Also, use the static Double.hashCode method to avoid creating a Double object:

public int hashCode()

{

return 7 * Objects.hashCode(name)

+ 11 * Double.hashCode(salary)

+ 13 * Objects.hashCode(hireDay);

}

Even better, when you need to combine multiple hash values, call Objects.hash with all of them. It will call Objects.hashCode for each argument and combine the values. Then the Employee.hashCode method is simply

public int hashCode()

{

return Objects.hash(name, salary, hireDay);

}

Your definitions of equals and hashCode must be compatible: If x.equals(y) is true, then x.hashCode() must return the same value as y.hashCode(). For example, if you define Employee.equals to compare employee IDs, then the hashCode method needs to hash the IDs, not employee names or memory addresses.

![]() Tip

Tip

If you have fields of an array type, you can use the static Arrays.hashCode method to compute a hash code composed of the hash codes of the array elements.

5.2.4 The toString Method

Another important method in Object is the toString method that returns a string representing the value of this object. Here is a typical example. The toString method of the Point class returns a string like this:

java.awt.Point[x=10,y=20]

Most (but not all) toString methods follow this format: the name of the class, then the field values enclosed in square brackets. Here is an implementation of the toString method for the Employee class:

public String toString()

{

return "Employee[name=" + name

+ ",salary=" + salary

+ ",hireDay=" + hireDay

+ "]";

}

Actually, you can do a little better. Instead of hardwiring the class name into the toString method, call getClass().getName() to obtain a string with the class name.

public String toString()

{

return getClass().getName()

+ "[name=" + name

+ ",salary=" + salary

+ ",hireDay=" + hireDay

+ "]";

}

Such toString method will also work for subclasses.

Of course, the subclass programmer should define its own toString method and add the subclass fields. If the superclass uses getClass().getName(), then the subclass can simply call super.toString(). For example, here is a toString method for the Manager class:

public class Manager extends Employee

{

...

public String toString()

{

return super.toString()

+ "[bonus=" + bonus

+ "]";

}

}

Now a Manager object is printed as

Manager[name=...,salary=...,hireDay=...][bonus=...]

The toString method is ubiquitous for an important reason: Whenever an object is concatenated with a string by the “+” operator, the Java compiler automatically invokes the toString method to obtain a string representation of the object. For example:

Point p = new Point(10, 20);

String message = "The current position is " + p;

// automatically invokes p.toString()

![]() Tip

Tip

Instead of writing x.toString(), you can write "" + x. This statement concatenates the empty string with the string representation of x that is exactly x.toString(). Unlike toString, this statement even works if x is of primitive type.

If x is any object and you call

System.out.println(x);

then the println method simply calls x.toString() and prints the resulting string.

The Object class defines the toString method to print the class name and the hash code of the object. For example, the call

System.out.println(System.out)

produces an output that looks like this:

java.io.PrintStream@2f6684

The reason is that the implementor of the PrintStream class didn’t bother to override the toString method.

Annoyingly, arrays inherit the toString method from Object, with the added twist that the array type is printed in an archaic format. For example,

int[] luckyNumbers = { 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13 };

String s = "" + luckyNumbers;

yields the string "[I@1a46e30". (The prefix [I denotes an array of integers.) The remedy is to call the static Arrays.toString method instead. The code

String s = Arrays.toString(luckyNumbers);

yields the string "[2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13]".

To correctly print multidimensional arrays (that is, arrays of arrays), use Arrays.deepToString.

The toString method is a great tool for logging. Many classes in the standard class library define the toString method so that you can get useful information about the state of an object. This is particularly useful in logging messages like this:

System.out.println("Current position = " + position);

As we explain in Chapter 7, an even better solution is to use an object of the Logger class and call

Logger.global.info("Current position = " + position);

![]() Tip

Tip

We strongly recommend that you add a toString method to each class that you write. You, as well as other programmers who use your classes, will be grateful for the logging support.

The program in Listing 5.8 implements the equals, hashCode, and toString methods for the classes Employee (Listing 5.9) and Manager (Listing 5.10).

Listing 5.8 equals/EqualsTest.java

1 package equals;

2

3 /**

4 * This program demonstrates the equals method.

5 * @version 1.12 2012-01-26

6 * @author Cay Horstmann

7 */

8 public class EqualsTest

9 {

10 public static void main(String[] args)

11 {

12 Employee alice1 = new Employee("Alice Adams", 75000, 1987, 12, 15);

13 Employee alice2 = alice1;

14 Employee alice3 = new Employee("Alice Adams", 75000, 1987, 12, 15);

15 Employee bob = new Employee("Bob Brandson", 50000, 1989, 10, 1);

16

17 System.out.println("alice1 == alice2: " + (alice1 == alice2));

18

19 System.out.println("alice1 == alice3: " + (alice1 == alice3));

20

21 System.out.println("alice1.equals(alice3): " + alice1.equals(alice3));

22

23 System.out.println("alice1.equals(bob): " + alice1.equals(bob));

24

25 System.out.println("bob.toString(): " + bob);

26

27 Manager carl = new Manager("Carl Cracker", 80000, 1987, 12, 15);

28 Manager boss = new Manager("Carl Cracker", 80000, 1987, 12, 15);

29 boss.setBonus(5000);

30 System.out.println("boss.toString(): " + boss);

31 System.out.println("carl.equals(boss): " + carl.equals(boss));

32 System.out.println("alice1.hashCode(): " + alice1.hashCode());

33 System.out.println("alice3.hashCode(): " + alice3.hashCode());

34 System.out.println("bob.hashCode(): " + bob.hashCode());

35 System.out.println("carl.hashCode(): " + carl.hashCode());

36 }

37 }

Listing 5.9 equals/Employee.java

1 package equals;

2

3 import java.time.*;

4 import java.util.Objects;

5

6 public class Employee

7 {

8 private String name;

9 private double salary;

10 private LocalDate hireDay;

11

12 public Employee(String name, double salary, int year, int month, int day)

13 {

14 this.name = name;

15 this.salary = salary;

16 hireDay = LocalDate.of(year, month, day);

17 }

18

19 public String getName()

20 {

21 return name;

22 }

23

24 public double getSalary()

25 {

26 return salary;

27 }

28

29 public LocalDate getHireDay()

30 {

31 return hireDay;

32 }

33

34 public void raiseSalary(double byPercent)

35 {

36 double raise = salary * byPercent / 100;

37 salary += raise;

38 }

39

40 public boolean equals(Object otherObject)

41 {

42 // a quick test to see if the objects are identical

43 if (this == otherObject) return true;

44

45 // must return false if the explicit parameter is null

46 if (otherObject == null) return false;

47

48 // if the classes don't match, they can't be equal

49 if (getClass() != otherObject.getClass()) return false;

50

51 // now we know otherObject is a non-null Employee

52 Employee other = (Employee) otherObject;

53

54 // test whether the fields have identical values

55 return Objects.equals(name, other.name) && salary == other.salary

56 && Objects.equals(hireDay, other.hireDay);

57 }

58

59 public int hashCode()

60 {

61 return Objects.hash(name, salary, hireDay);

62 }

63

64 public String toString()

65 {

66 return getClass().getName() + "[name=" + name + ",salary=" + salary + ",hireDay=" + hireDay

67 + "]";

68 }

69 }

Listing 5.10 equals/Manager.java

1 package equals;

2

3 public class Manager extends Employee

4 {

5 private double bonus;

6

7 public Manager(String name, double salary, int year, int month, int day)

8 {

9 super(name, salary, year, month, day);

10 bonus = 0;

11 }

12

13 public double getSalary()

14 {

15 double baseSalary = super.getSalary();

16 return baseSalary + bonus;

17 }

18

19 public void setBonus(double bonus)

20 {

21 this.bonus = bonus;

22 }

23

24 public boolean equals(Object otherObject)

25 {

26 if (!super.equals(otherObject)) return false;

27 Manager other = (Manager) otherObject;

28 // super.equals checked that this and other belong to the same class

29 return bonus == other.bonus;

30 }

31

32 public int hashCode()

33 {

34 return java.util.Objects.hash(super.hashCode(), bonus)

35 }

36

37 public String toString()

38 {

39 return super.toString() + "[bonus=" + bonus + "]";

40 }

41 }

5.3 Generic Array Lists

In many programming languages—in particular, in C++—you have to fix the sizes of all arrays at compile time. Programmers hate this because it forces them into uncomfortable trade-offs. How many employees will be in a department? Surely no more than 100. What if there is a humongous department with 150 employees? Do we want to waste 90 entries for every department with just 10 employees?

In Java, the situation is much better. You can set the size of an array at runtime.

int actualSize = . . .;

Employee[] staff = new Employee[actualSize];

Of course, this code does not completely solve the problem of dynamically modifying arrays at runtime. Once you set the array size, you cannot change it easily. Instead, in Java you can deal with this common situation by using another Java class, called ArrayList. The ArrayList class is similar to an array, but it automatically adjusts its capacity as you add and remove elements, without any additional code.

ArrayList is a generic class with a type parameter. To specify the type of the element objects that the array list holds, you append a class name enclosed in angle brackets, such as ArrayList<Employee>. You will see in Chapter 8 how to define your own generic class, but you don’t need to know any of those technicalities to use the ArrayList type.

Here we declare and construct an array list that holds Employee objects:

ArrayList<Employee> staff = new ArrayList<Employee>();

It is a bit tedious that the type parameter Employee is used on both sides. As of Java SE 7, you can omit the type parameter on the right-hand side:

ArrayList<Employee> staff = new ArrayList<>();

This is called the “diamond” syntax because the empty brackets <> resemble a diamond. Use the diamond syntax together with the new operator. The compiler checks what happens to the new value. If it is assigned to a variable, passed into a method, or returned from a method, then the compiler checks the generic type of the variable, parameter, or method. It then places that type into the <>. In our example, the new ArrayList<>() is assigned to a variable of type ArrayList<Employee>. Therefore, the generic type is Employee.

![]() Note

Note

Before Java SE 5.0, there were no generic classes. Instead, there was a single ArrayList class, a one-size-fits-all collection that holds elements of type Object. You can still use ArrayList without a <...> suffix. It is considered a “raw” type, with the type parameter erased.

![]() Note

Note

In even older versions of Java, programmers used the Vector class for dynamic arrays. However, the ArrayList class is more efficient, and there is no longer any good reason to use the Vector class.

Use the add method to add new elements to an array list. For example, here is how you populate an array list with employee objects:

staff.add(new Employee("Harry Hacker", . . .));

staff.add(new Employee("Tony Tester", . . .));

The array list manages an internal array of object references. Eventually, that array will run out of space. This is where array lists work their magic: If you call add and the internal array is full, the array list automatically creates a bigger array and copies all the objects from the smaller to the bigger array.

If you already know, or have a good guess, how many elements you want to store, call the ensureCapacity method before filling the array list:

staff.ensureCapacity(100);

That call allocates an internal array of 100 objects. Then, the first 100 calls to add will not involve any costly reallocation.

You can also pass an initial capacity to the ArrayList constructor:

ArrayList<Employee> staff = new ArrayList<>(100);

![]() Caution

Caution

Allocating an array list as

new ArrayList<>(100) // capacity is 100

is not the same as allocating a new array as

new Employee[100] // size is 100

There is an important distinction between the capacity of an array list and the size of an array. If you allocate an array with 100 entries, then the array has 100 slots, ready for use. An array list with a capacity of 100 elements has the potential of holding 100 elements (and, in fact, more than 100, at the cost of additional reallocations)—but at the beginning, even after its initial construction, an array list holds no elements at all.

The size method returns the actual number of elements in the array list. For example,

staff.size()

returns the current number of elements in the staff array list. This is the equivalent of

a.length

for an array a.

Once you are reasonably sure that the array list is at its permanent size, you can call the trimToSize method. This method adjusts the size of the memory block to use exactly as much storage space as is required to hold the current number of elements. The garbage collector will reclaim any excess memory.

Once you trim the size of an array list, adding new elements will move the block again, which takes time. You should only use trimToSize when you are sure you won’t add any more elements to the array list.

The ArrayList class is similar to the C++ vector template. Both ArrayList and vector are generic types. But the C++ vector template overloads the [] operator for convenient element access. Java does not have operator overloading, so it must use explicit method calls instead. Moreover, C++ vectors are copied by value. If a and b are two vectors, then the assignment a = b makes a into a new vector with the same length as b, and all elements are copied from b to a. The same assignment in Java makes both a and b refer to the same array list.

5.3.1 Accessing Array List Elements

Unfortunately, nothing comes for free. The automatic growth convenience that array lists give requires a more complicated syntax for accessing the elements. The reason is that the ArrayList class is not a part of the Java programming language; it is just a utility class programmed by someone and supplied in the standard library.

Instead of the pleasant [] syntax to access or change the element of an array, you use the get and set methods.

For example, to set the ith element, you use

staff.set(i, harry);

This is equivalent to

a[i] = harry;

for an array a. (As with arrays, the index values are zero based.)

![]() Caution

Caution

Do not call list.set(i, x) until the size of the array list is larger than i. For example, the following code is wrong:

ArrayList<Employee> list = new ArrayList<>(100); // capacity 100, size 0

list.set(0, x); // no element 0 yet

Use the add method instead of set to fill up an array, and use set only to replace a previously added element.

To get an array list element, use

Employee e = staff.get(i);

This is equivalent to

Employee e = a[i];

![]() Note

Note

When there were no generic classes, the get method of the raw ArrayList class had no choice but to return an Object. Consequently, callers of get had to cast the returned value to the desired type:

Employee e = (Employee) staff.get(i);

The raw ArrayList is also a bit dangerous. Its add and set methods accept objects of any type. A call

staff.set(i, "Harry Hacker");

compiles without so much as a warning, and you run into grief only when you retrieve the object and try to cast it. If you use an ArrayList<Employee> instead, the compiler will detect this error.

You can sometimes get the best of both worlds—flexible growth and convenient element access—with the following trick. First, make an array list and add all the elements:

ArrayList<X> list = new ArrayList<>();

while (. . .)

{

x = . . .;

list.add(x);

}

When you are done, use the toArray method to copy the elements into an array:

X[] a = new X[list.size()];

list.toArray(a);

Sometimes, you need to add elements in the middle of an array list. Use the add method with an index parameter:

int n = staff.size() / 2;

staff.add(n, e);

The elements at locations n and above are shifted up to make room for the new entry. If the new size of the array list after the insertion exceeds the capacity, the array list reallocates its storage array.

Similarly, you can remove an element from the middle of an array list:

Employee e = staff.remove(n);

The elements located above it are copied down, and the size of the array is reduced by one.

Inserting and removing elements is not terribly efficient. It is probably not worth worrying about for small array lists. But if you store many elements and frequently insert and remove in the middle of a collection, consider using a linked list instead. We explain how to program with linked lists in Chapter 9.

You can use the “for each” loop to traverse the contents of an array list:

for (Employee e : staff)

do something with e

This loop has the same effect as

for (int i = 0; i < staff.size(); i++)

{

Employee e = staff.get(i);

do something with e

}

Listing 5.11 is a modification of the EmployeeTest program of Chapter 4. The Employee[] array is replaced by an ArrayList<Employee>. Note the following changes:

• You don’t have to specify the array size.

• You use add to add as many elements as you like.

• You use size() instead of length to count the number of elements.

• You use a.get(i) instead of a[i] to access an element.

Listing 5.11 arrayList/ArrayListTest.java

1 package arrayList;

2

3 import java.util.*;

4

5 /**

6 * This program demonstrates the ArrayList class.

7 * @version 1.11 2012-01-26

8 * @author Cay Horstmann

9 */

10 public class ArrayListTest

11 {

12 public static void main(String[] args)

13 {

14 // fill the staff array list with three Employee objects

15 ArrayList<Employee> staff = new ArrayList<>();

16

17 staff.add(new Employee("Carl Cracker", 75000, 1987, 12, 15));

18 staff.add(new Employee("Harry Hacker", 50000, 1989, 10, 1));

19 staff.add(new Employee("Tony Tester", 40000, 1990, 3, 15));

20