Chapter 5

Articulating Opposing Models

In early 2013, Jennifer was asked to teach in an advanced health-leadership program at the Rotman School. It was a last-minute request, and she was a touch nervous. For the first time, she was adapting our integrative thinking material to a health-care context, and she worried that typical business examples might not resonate with the doctors, nurses, and other health professionals in the class. So she sought advice from our friend Melanie Carr, a psychiatrist who had been an important early collaborator on the theory of integrative thinking. Carr had been ably teaching integrative thinking in similar health-care programs for a few years, and her advice was clear: definitely avoid corporate examples, and instead ground the exercises in the health-care context as much as possible. She even suggested an exercise topic: vaccines.

To most of us, vaccines represent one of the most important medical advances of the past century. Among Americans born between 1994 and 2013, vaccination will prevent an estimated 322 million illnesses, 21 million hospitalizations, and more than 700,000 early deaths.1 Once upon a time, as many as 4 million people contracted measles each year. Thanks to the introduction of an effective vaccine in 1963, along with decades of intensive work by health professionals, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared in 2000 that the disease had been eliminated.

But not so fast. Just before that declaration, Andrew Wakefield had published an article in the Lancet linking the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine with autism.2 Although the article later was thoroughly discredited and Wakefield barred from practicing medicine, it was enough to boost a nascent antivaccine movement. In the years since, the “antivax” movement has grown dramatically, with advocates such as Robert Kennedy Jr. and Jenny McCarthy publicly questioning the safety of vaccines in general and the MMR vaccine in particular.

The resulting effect—parents failing to have their children vaccinated—although small in absolute numbers, is worrisome. The United States as a whole maintains vaccination rates for MMR at more than 90 percent, but in seventeen states MMR vaccinations dip below the 90 percent hurdle rate required to achieve herd immunity (the rate at which enough people are vaccinated to protect the entire community from potential outbreaks, including among those too young or too ill to be vaccinated).3 Interestingly, low vaccination rates occur broadly, including in places of privilege; only 84 percent of students entering kindergarten in wealthy Marin County, California, are fully vaccinated.4 The oil-rich province of Alberta, Canada, has a measles immunization rate of slightly less than 86 percent.5 Both regions have seen measles outbreaks in recent years. In the face of the antivax movement, measles is making a comeback.

All of this context convinced Jennifer that the issue would make for an interesting exploration of opposing ideas, so she blithely announced to a roomful of health-care practitioners that their topic for the afternoon would the vaccine debate. There was a pause, and then a booming voice from the back of the room: “Excuse me, but there is no debate about vaccines!” Heads nodded, and voices murmured general agreement.

But then one participant bravely piped up: “Isn’t there, though? We act as if there is no debate, and, medically, that’s true. So then why are fewer people vaccinating their kids? Maybe we need to acknowledge that there really is a debate. And we are losing it.” For two decades, the medical community has presented fact after scientific fact in support of vaccines. It has, for all intents and purposes, demonized people who do not vaccinate their children. Yet the antivax movement has dug in its heels—and has even grown—in response. Perhaps, the class finally agreed, it might be time for a different approach. To influence those who oppose vaccinations, they determined, the medical community might need to truly understand the antivax model of the world.

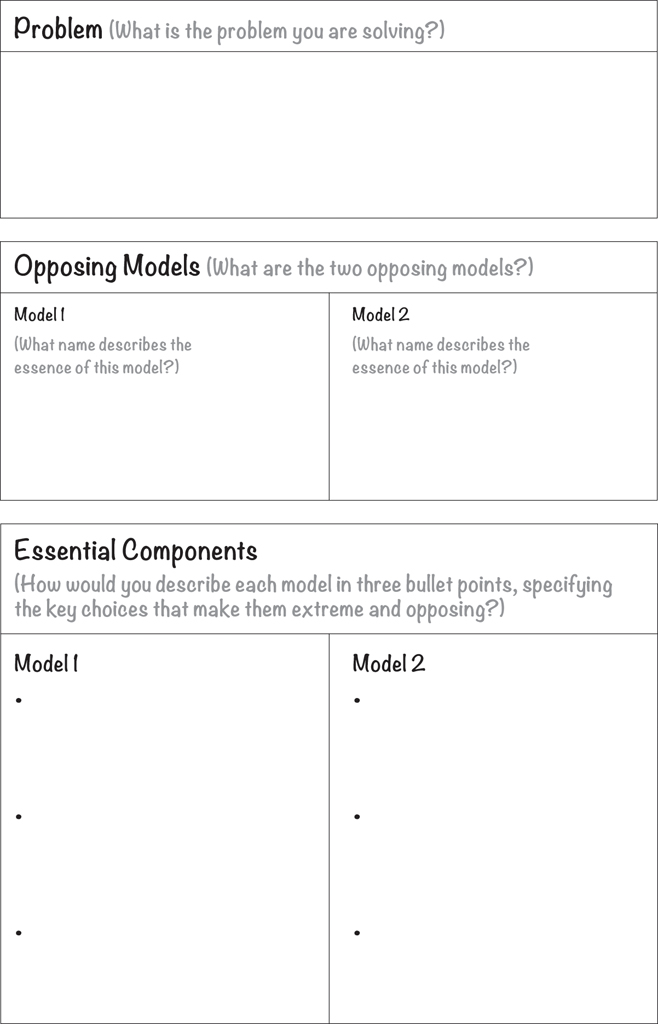

Understanding opposing models—even, or perhaps especially, those that make us deeply uncomfortable—is what the first stage of the integrative thinking process is all about. It begins with defining the problem, then identifying two opposing models that could solve that problem, and, finally, exploring how each of these opposing models works, with the aim of getting to an articulation of the core value that each model might provide. The intention is not to help you choose between these opposing models, but to help you use the opposing models to create a great, new choice.

This first stage can be tough, as the vaccine example illustrates. The problem with opposing models is that sometimes only one of the models feels like the right answer. Vaccines, to these health-care folks, are the right answer. Parents who advocate for the right to choose whether or not their child should be vaccinated (or to what extent or on what schedule) are treated as antiscientific, irresponsible, illogical, and even immoral. Given what you’ve learned about cognitive biases, it should come as no surprise that those in the antivax movement reject this assessment and refuse to listen to those who have characterized them in these ways.

Recall the study cited earlier that demonstrated the effect of introducing contradictory evidence to people with strongly held views: the contradictory evidence actually produces entrenchment in the original belief, rather than changed minds. Throwing science at parents worried about vaccines has had just that effect. That the medical establishment continues to do so—repeatedly, in the same ways—is a failure of empathy. As many of us might in a similar situation, they continue to enforce on other people their own views of what is valid evidence, and their own models, without considering what those other people believe and why they believe it. Such an approach is unlikely to produce outcomes that are different from the ones they are producing now.

GET BEYOND STUPID OR EVIL

Blindly berating those who hold opposing models happens in other contexts as well, such as politics and economics. In politics, conservatives tend to see liberals as hopelessly naive, building unaffordable entitlement schemes the country can ill afford. And liberals typically see conservatives as unfeeling and unkind, more interested in money than in people. These characterizations are not a million miles from stupid (liberals) and evil (conservatives).

Jonathan Haidt has captured a similar tension in his work on capitalism. He argues that a pitched battle is playing out between two opposing narratives in economics: one side of the spectrum sees capitalism as exploitation; the other sees it as liberation.6 One side says we need a strong hand to prevent the worst effects of free markets; the other says we will be better off if we let the markets run as they will. Haidt argues that we need a new narrative to replace these dueling ones. Because, without the creation of an integrated, alternative narrative, what is the natural result of the fundamental tensions embedded in the existing narratives? Political gridlock, an increasing gulf between the left and the right, and the end of meaningful dialogue across the political spectrum. We wind up talking only to those who already agree with us and disconnecting from the other side. It’s simple pragmatism. Why bother listening to someone who is wrong? What is to be gained?

As it turns out, we stand to gain a great deal. Listening only to those who agree with us reinforces our existing views, blinds us to the flaws in our reasoning, and limits the creativity of our thinking. And it can have real-world negative effects on individual and organizational performance. In one study, researchers found that CEOs overrely on advice from executives who share a common functional background, friendship ties, or employment in the same industry, especially when a company is performing poorly. The more such leaders seek advice from those like them, the less likely these leaders are to change the firm’s strategy, despite its poor performance. “It appears,” the authors wrote, “that poorly performing firms are ultimately less likely to improve and more likely to get worse as a result of CEOs’ seeking advice from executives at other firms.”7

It’s no surprise. Friends and peers from similar backgrounds tend to agree with us. It is a manifestation of groupthink, in which a group reaches a consensus decision without critical evaluation of alternative viewpoints, often having actively suppressed dissenting viewpoints. Studies indicate that groupthink happens most often when a group is homogenous and insulated from outside perspectives. Consider those conditions, and then think about most corporate boardrooms and senior leadership teams; how much diversity of context, experience, and perspective do they contain? And how much of their discussion processes are aimed at surfacing disagreement? Virtually none at all. In most boardrooms, in our experience, the drive for consensus means the board quickly converges around the majority opinion. A cynic might say that very little thinking happens in those rooms.

By contrast, as Charlan Nemeth has noted, exposure to minority views makes us think harder. “Those exposed to minority views are stimulated to attend to more aspects of the situation, they think in more divergent ways and they are more likely to detect novel solutions or come to new decisions,” she wrote.8 This is true even when, as in the case of vaccines, the minority view is “invalid” by most standards. As Adam Grant puts it in his book Originals, “Dissenting opinions are useful, even when they are wrong.”9

Going back to our health-care practitioners, Jennifer asked the group to carefully consider opposing models for the administration of vaccines. On one hand was a model in which vaccines are mandated entirely by the government (Canada is a publicly funded health-care system, so such an approach is not far from the current model in use). In this model, decision makers within the public system would mandate a series and schedule of vaccines for all children, and parents would have no choice but to comply (for instance, unvaccinated kids would not be allowed to attend public schools and parents could be subject to an array of punishments). On the other hand was a model in which no vaccines were mandated and all choices about vaccines were made by the parents.

This second model made the health-care workers extraordinarily uncomfortable. But, after struggling with it for a while, they came to see some important potential benefits from the parent-choice model. (For example, the parent-choice model recognizes that the parent is ultimately most responsible and accountable for a child’s well-being. Under such a model, health-care workers would be pushed to do a better job of engaging with skeptical parents and finding new modes of influence when a mandate was no longer on the table.) At the end of the discussion the group agreed that, at the very least, a deeper understanding of the parent-choice model could help shift the way we talk about vaccines to the public at large and help reverse the antivax trend.

Try This

To surface and explore dissenting opinions, we need ground rules that enable everyone in a group to discuss the problem, regardless of their own perspectives on the existing models. Simply telling people to have a productive dialogue on an issue isn’t enough. Without real tools, this admonition falls into the category of unactionable advice, like “Grow taller.” We would if we could! This is where the integrative thinking process comes in.

Here, at the outset of the process, you are setting yourself up to think differently about a problem you face. In this phase, you take the following steps.

Define the problem.

Identify two extreme and opposing answers to the problem.

Sketch out the two opposing ideas.

Lay out how each model works.

Each step is critical to the social process of problem solving and to leveraging diverse perspectives to create superior answers. It all begins with defining the problem.

DEFINE THE PROBLEM

Writing about a theory of inquiry in 1938, John Dewey noted that “it is a familiar and significant saying that a problem well put is half-solved . . . Without a problem, there is blind groping in the dark.”10 We agree. Without at least a provisional agreement as to the problem to be solved, groups tend to argue rather than make progress. They tend to obsess about symptoms and inputs, complain that the world is too complex, and then break the problem into small, manageable pieces. As A.G. Lafley likes to say, they fail to come to grips with reality.

In integrative thinking, we start by seeking a simple articulation, or framing, of a problem that is worth solving. A problem worth solving is one that matters. It is one that is meaningful to the individuals tasked with solving it. And it needn’t be a problem with world-shaking implications or one that’s faced only by Fortune 500 CEOs.

Here’s one example of problem framing from a group of students consulting to the manager of a community garden. The manager had noticed that some of the food was being picked improperly. This wasn’t a terribly big deal, but it bothered him because it suggested that community members were coming to the garden after hours and helping themselves to the produce. If true, this raised the tricky issue of how best to respond. Were he to crack down on access, he would reduce the community’s sense of ownership and responsibility for the garden. But if he did nothing, he would be rewarding freeloaders at the expense of those who dedicated their time and energy to the garden. Left unchecked, the current situation could lead to distrust and dysfunction, ultimately shutting down the whole project. So how should the manager think about ownership of, and access to, the garden, in order to increase the chances of long-term success for the project? This problem, for the students and the manager, was one worth solving.

Framing the problem is a matter of creating a short statement that captures the essence of the problem to be solved. Don’t obsess about finding the perfect words; you can refine the problem statement later if you feel the need. At this point, focus instead on ensuring that your team has a shared understanding of the provisional problem and a shared commitment to solving it. So don’t wordsmith, but do consider using a brilliantly helpful phase from design thinking: try beginning your problem statement with the words, “How might we . . .” Min Basadur, who helped popularize the phrase, says, “People may start out asking, ‘How can we do this,’ or ‘How should we do that?’. . . But as soon as you start using words like can and should, you’re implying judgment: ‘Can we really do it? And should we?’” By using the word might, instead of can or should, he says, “you’re able to defer judgment, which helps people to create options more freely, and opens up more possibilities.”11

Your problem, then, should be framed in a way that helps people imagine that an answer might be possible. How might we, for instance, create a model for governance of a community garden that could ensure the garden’s longevity? With such a question in mind, you can move on to engage with opposing models.

Try This

IDENTIFY TWO EXTREME AND OPPOSING MODELS

When we first started teaching integrative thinking, we framed it as a tool to be used in those moments when you face a difficult trade-off: a clear but unappealing either-or choice. We presented it in this way because when we had asked highly successful leaders to share their most difficult choices, they almost always did so by articulating an untenable either-or dilemma: When he became CEO, A.G. Lafley could either fix P&G’s financials in the short run or invest in innovation to win in the long run. When launching the Four Seasons, Isadore Sharp could either build small, friendly, but economically tenuous motels, or he could build large, luxurious convention hotels that would be financially sustainable but cold and impersonal for guests. At Red Hat, Bob Young could embrace either the free software model or the proprietary model. Based on interviews, for years, we taught integrative thinking as a tool to be used when life hands you one of those tough either-or situations.

But as we did so, we came to see that beginning with an abstract problem (How should I think about the right level of investment in innovation? What is the right business model for my hotels? What kind of a software company do I want to build?) and moving to a clear choice between two opposing choices is a powerful way to progress toward a solution, whether or not the final choice is clear from the outset. This insight led us to wonder, What if the world didn’t hand either-or choices to our integrative thinkers? What if the world instead gave them a wicked problem and they instinctively converted the problem into an either-or choice as a way to help them think about the problem more effectively? If this were the case, perhaps we could help those learning to solve tough problems to do the same thing.

What might this look like? Consider a sales director we met in an executive MBA class. She was working for a wire-mesh distributor. The organization had recently acquired a competitor and was struggling with the integration of the two firms. One particularly knotty issue was the question of how to structure the sales force. One of the companies had a large direct sales force, whereas the other had traditionally relied on wholesale dealers to sell to the end user. With the merger, the sales teams had to be integrated, but what was the best way to do that? The debate had raged for months, with little progress toward an answer. The sales director feared that the organization would spend even more time talking about the problem, studying best practices, surveying stakeholders, and crunching the numbers, and yet wind up no more certain of the best way to move ahead. To avoid that, she asked her team to move from a general consideration of the problem (we need to integrate these two sales forces) to a defined articulation of two opposing models that might solve the problem (we need to either go direct or go through dealers). As they proceeded, we encouraged the team members to focus on the two most extreme versions of the sales models: an entirely direct-sales model and a dealer-only model. The problem as it was provisionally framed, then, was this: How might we create an integrated sales model that captures the best parts of the all-direct-sales and dealer-only models? With the problem framed in this way, the team was able to analyze its choices productively and soon came to an answer in which a small, focused direct sales force would treat the dealers as its customers, upskilling and supporting this much broader dealer network, which would then be far better equipped to serve the end customers.

Why begin with two extreme and opposing models? We start with two models primarily because it is a lot better than one model. Translating a problem into a two-sided choice raises the emotional temperature and provides momentum to the group process. Factions on both sides start to grapple with the implications of the choice. You want, as Alfred Sloan did, to use disagreement to help you understand the real issue and the potential solutions. Exploring more than one model also provides a fail-safe defense against confirmation bias, groupthink, and a too-early commitment to any single answer.

So starting with two models is better than starting with one, but it is also better than starting with ten models. Seeking to deeply understand ten models would be an almost overwhelming task. Choosing two models instead provides a manageable starting place. It is a way to navigate the complexity of the situation that isn’t paralyzing right off the bat.

We use opposing models rather than any two models to produce helpful tension. We learned from Roger’s early interviews with integrative thinkers that the tension between ideas often helped spur creative thinking. It was only when engaged in the constraining consideration of opposites—each of which had value but could not be adopted at the same time as the other—that the highly successful leaders found helpful insights. So to keep you in a state of consideration rather than evaluation (considering what each model is all about rather than evaluating whether each model is good or bad), make the models as opposing as you can. This state of consideration can provide the time and space to challenge assumptions and provoke new thinking.

Try This

We make the opposing models extreme because we find that starting with extreme models helps depersonalize the models and separate people from ideas. Often, the models are even more extreme than those supported by individuals in the room. By pushing the models away from the “realistic” options already on the table, we make it easier for the group to consider the models as ideas rather than as a threat to the status quo.

Pushing the models to extremes means that, by definition, you eliminate consideration of compromises—answers that already contain elements of multiple models. In our sales force example, for instance, we wouldn’t start by considering a sales model that serves some customers directly and other customers via dealers, with individual leaders deciding which path to follow on a case-by-case basis. Such a compromise might be on the table for the organization, but it isn’t very helpful in creating an integrative answer. Integrative thinking isn’t about “doing both” but rather about finding an answer that takes the best of both to produce outcomes that are preferable to existing ones. Compromises are less helpful to the process of creating a better answer, because they are very hard to parse. The effects of different models are meshed together, and they become even more muddled as we seek to go deeper into how each model works. In practice, we’ve found there simply isn’t as much to learn from compromises; there isn’t enough tension between the ideas to give us room to create (see figure 5-2).

In some cases, there will be a third choice that is fundamentally different from the first two—an alternative extreme option. For instance, the third choice for the wire-mesh company might be to shift to an entirely online sales model. If you really have three opposing models, and if folks around the table are committed to exploring them, by all means consider all three models. But keep in mind that this approach will increase the complexity of the exercise and likely will increase the time it will take to think through the problem. Take care to ensure that the third extreme and opposing model isn’t a compromise in disguise.

As with framing the problem, don’t spend a lot of time obsessing about finding just the right opposing models. For your purposes, these are prototype models, just as your problem framing is a provisional one. Your opposing models are a starting place for the process of creating new answers. So rather than seek perfection, just check this: Are the opposing models an answer to the problem as framed? Sometimes, you can default to answers that are tangential to the problem or don’t really speak to the core of the issue.

Figure 5-2. Extremes Rather Than Compromises

What does this look like? For a number of years, the decline of the Canadian tech firm BlackBerry was so much in the news that we had a slew of student projects on how to save the company. The most successful homed in on a central strategic choice—such as whether to reinvest to win in hardware, or shift to become a software company, or whether to go after the enterprise market or target the consumer market. Less successful were the projects that defined the problem broadly (how to address declining sales in an intensely competitive market) and then sought to tackle it via opposing models that addressed a small sliver of that problem (such as whether to do app development internally or create a more open application platform).

To avoid this disconnect, you need to work to tie the choices directly to the problem to be solved; the opposing models should be extremely distinct ways to go about solving that particular problem. Once you have identified your extreme and opposing models, you can move to the next step and begin to sketch them.

Try This

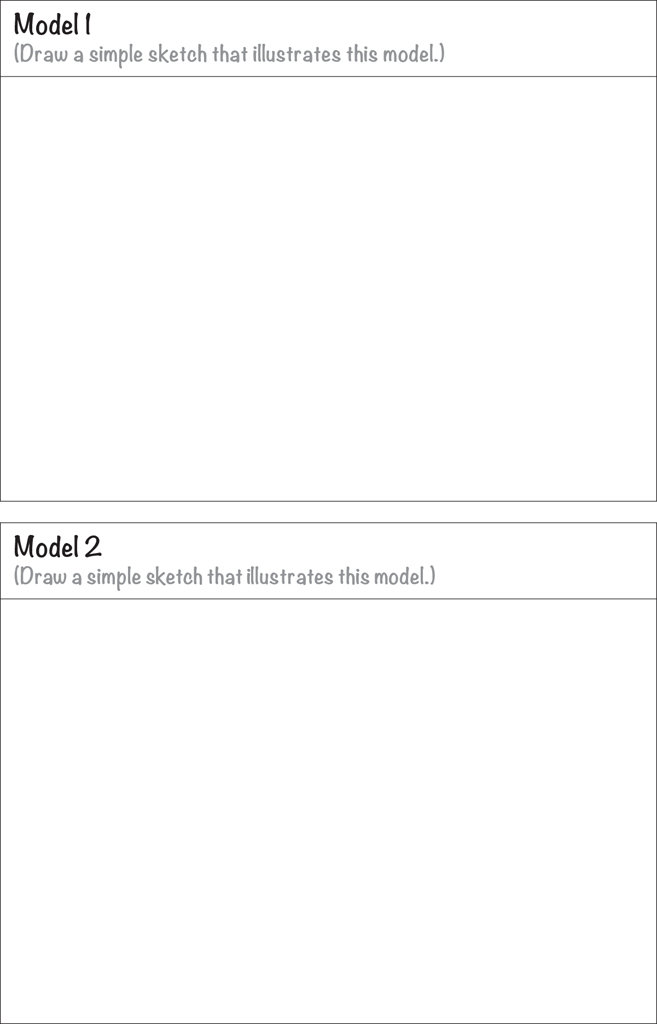

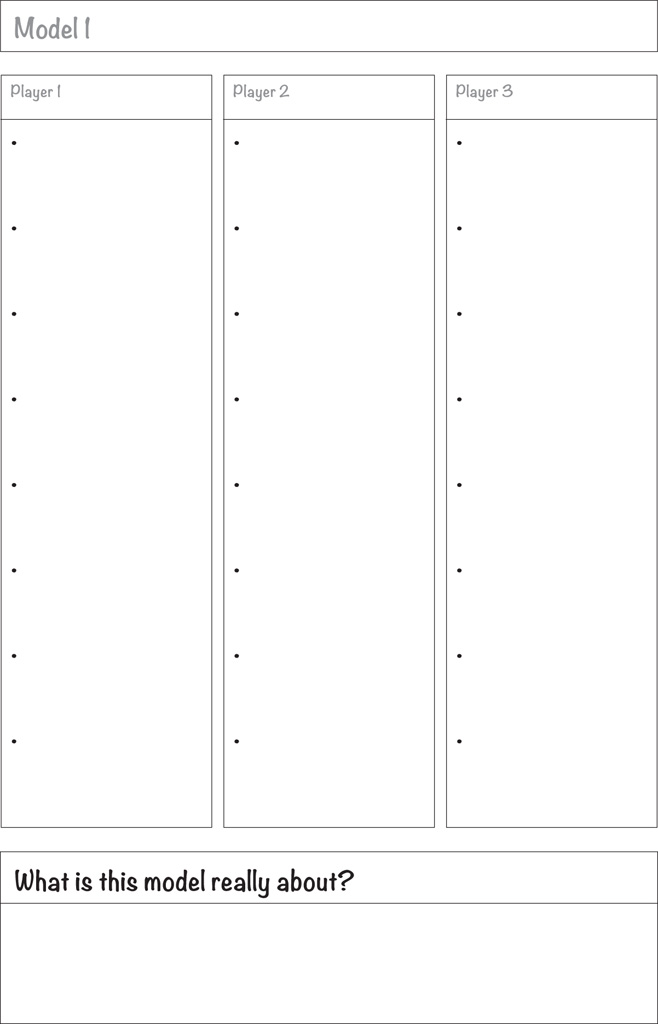

SKETCH THE MODELS

Have you ever had a discussion with a colleague, come to agreement, and subsequently discovered that you didn’t actually agree at all, because you were using the same word to mean different things? That’s why it is important to sketch the opposing models under consideration. Sketching the models means describing them in enough detail that an observer could quickly understand the essence of each one. It is taking the time to explain—in a few sentences, bullet points, or even pictures—what each model would look like in practice. Sketching the models helps a group ensure that all the participants are talking about the same thing; it teases out and articulates the tension between the ideas, and it helps make the choice concrete for the group.

How does that work? Let’s consider a challenge presented to our MBA students a few years ago by the CEO of one of Canada’s largest banks. The CEO was struggling to break through in a structurally attractive but largely undifferentiated financial services marketplace. The big push in the organization for the previous five years had been efficiency: simplification and digitization to drive down costs and remove unnecessary complexity. Now he worried that the effort had produced an organization that was blind to its customers’ other needs. “We want to be the bank that defines great customer experience,” he explained. “And I worry that my people are constantly trading off between customer experience and efficiency.”

A Problem Worth Solving

We offered the challenge to our students. They were unimpressed with the opposing models as described (great service versus efficiency), and they told us so. How is this a problem, they asked, let alone one worth solving? Great service is efficient service, they argued. How hard is that to see?

Given that the CEO had identified this as one of his most pressing issues and that we know him to be a very smart guy, we pushed the students to take another look at the problem and the models. We asked them to think harder by taking the time to articulate two opposing models for the bank: one based on efficiency as the governing principle, and the other one based on customer experience as the most important value.

We asked the students to play out how a bank that was all about efficiency might look and feel different from one that was all about great experiences for customers. As they did so, the students came to realize that a bank that prioritizes efficiency would be as standardized as possible. Leading with technology (because computers are much more efficient than human beings), it would offer as few products as it could, making those products as simple as possible. It would have highly centralized and controlled processes, with no room for inefficient exceptions. See figure 5-3 for a simple sketch of this model, in the form of a storyboard.

Figure 5-3. All About Efficiency

Credit: Josie Fung, used with permission.

On the other hand, what would a bank built entirely around customer experience look like? It would look, the students said, the way the customer wanted it to look. Most likely, it would be highly customized to each customer, with lots of personal interaction, or none, depending on what the customer desired. It would offer each customer the suite of products and services that would be just right for that customer, regardless of the complexity produced by such an approach for the bank’s back-end systems. Such a bank would offer lots of different kinds of service, different kinds of locations, and highly flexible hours (see figure 5-4).

The tension between the two banking models started to emerge as the sketches took shape. Beneath the efficiency and experience models the students found rich tensions between standardization and customization, between an internal focus and an external one, between reliability (getting the same answer every time) and validity (getting the right answer this time). The students who most impressed the CEO at the final presentations took direct aim at these tensions.

Figure 5-4. All About Customer Experience

Credit: Josie Fung, used with permission.

Important Implications

Sketching the models may seem like a small step, but this task can have implications for the way teams think long after the step is completed. After a particular training program, one of our participants wanted to apply the integrative thinking process with her team. She worked in regional government and was responsible for the provision of autism support services. Her community had seen a significant increase in the number of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders but had not seen an equivalent increase in funding. For years, the team had struggled to do more with less, to compromise within constraints, and to make do. Now she wanted to see whether a better answer was possible.

Her starting place was to create a new framing of the problem as a distinct choice. Would the region take a broad approach, providing a little bit of support to every child diagnosed (the “spread out the peanut butter” model)? Or would it be more focused, recognizing that some children were in far greater need of support either because of the nature of their condition or because of social factors such as poverty (the “go where we are most needed” model)?

Sketching the models proved to be transformative for the team members, as they grappled to determine the kinds of services they could provide to all the children in the system, on the one hand, and with what it would look like to tell some families that no support would be available to them, on the other. Sketching the two models helped the team members express assumptions that had previously gone unspoken, to dig more deeply than they ever had into their own beliefs about the children they served, and to articulate sometimes-conflicting models of their duties as public servants. The discussion set up the team to explore its reason for existing and to define shared success criteria for new approaches.

Sketching the models needn’t be time intensive. The goal isn’t to create an exhaustive description but rather to gain general agreement about the core elements of each model. With the agreed-on elements defined for each model in turn, the group can move on to understanding more deeply how the two models work.

Try This

DEFINE HOW THE MODELS WORK

After you have sketched the two opposing models, what is the best way to understand them? When we first started teaching integrative thinking, we defaulted to a tool we already knew well. As children, we were told what to do when facing a difficult either-or choice: get out a legal pad, draw a line down the middle of the page, and start to list the pros and cons. Unfortunately, again and again, we saw teams hit dead ends on their lists of pros and cons. They would struggle to engage with the models, get bogged down in the drawbacks, and dismiss one or both of the models early on. Looking at pros and cons didn’t seem to change the conversation, and it didn’t seem to set the stage for a productive generation of possibilities.

So we implemented a new rule. At this stage of the process, as groups are seeking to understand the two models, to truly consider them, all talk of the negatives of the models is banned. The pro/con list becomes a pro/pro list, a name created by some clever students. Now, rather than list pros and cons, groups are asked to lay out the positives of each of the models. We ask teams to explore the benefits each model confers, determining why someone would choose it and what it ultimately produces that is worth having.

This approach—focusing only on the positives and not at all on the negatives—goes against conventional wisdom. But focusing on the positive effects of the models turns out to be important for three reasons.

Citing negatives can easily shut down consideration of a given model; if a particular drawback seems insurmountable at the outset, it is hard to continue to take that model seriously and to understand what might be valuable were that drawback to be overcome.

You want to understand what you could take from these models to create a great new choice. To create that new answer, it’s essential to understand the virtues, or what’s best, of each model. In that way you can later explore how those valuable elements might be incorporated into a new integrative model.

Focusing on the positives enables a more productive group process. Imagine your team is in a brainstorming session and your colleague Valeria comes up with a possible solution. The idea garners some support around the room and some momentum, until Julia, who has been silently sitting, arms crossed, leans forward and says, “Could I just, for a minute, play devil’s advocate?” Then she proceeds to explain why the idea could never work. In our experience, when that kind of thing happens there is an immediate physical shift in the room. All hope of generating new ideas dissipates. Why bother coming up with new ideas if Julia is just going to kill them?

Some of you may well be sitting with your metaphorical arms crossed right now, because you love playing the devil’s advocate. And didn’t we say that minority views need to be heard? Yes, but not before you’ve had a chance to explore what might be valuable in the models in front of you, and not while you’re seeking to generate new ideas. So the rule is that you don’t consider the drawbacks of the models at this early stage.

But there is good news if you’re the realist in the room—if you can’t imagine not including a discussion of the drawbacks of the models. If the models you’re considering are truly opposing, the negatives of one model should naturally be the positives of the other. For instance, if we note that decentralization provides agility, it isn’t necessary to say that centralized models are often bureaucratic and slow. In this way, you do get to include the negatives of each model, as long as you’re able to flip them around to be stated as positives of the opposing model. Now uncross your arms, and we’ll plow ahead.

When exploring the benefits of the models, you work in sequence and attempt to fall in love with each model. You consider, as deeply and thoughtfully as you can, what makes each model work well. You forget for the moment that other models exist. In this step, you do all you can to avoid judging or evaluating. The task isn’t to determine which model is best; rather, it’s to capture what a model offers that is worth having and how those valuable outcomes are produced.

The Key Players

Another key element of the pro/pro chart emerged early in our articulation of the integrative thinking process during a session Roger held with a category team at P&G. As it turns out, if we only think about how the organization benefits from each model, we are leaving out a great deal. Instead, we ask teams to look at each model from a few different perspectives—exercising empathy for the most important other players in the situation. To choose the perspectives, we ask, “Who matters to the decision? Who has to support the new answer? And who is most affected by the choice?”

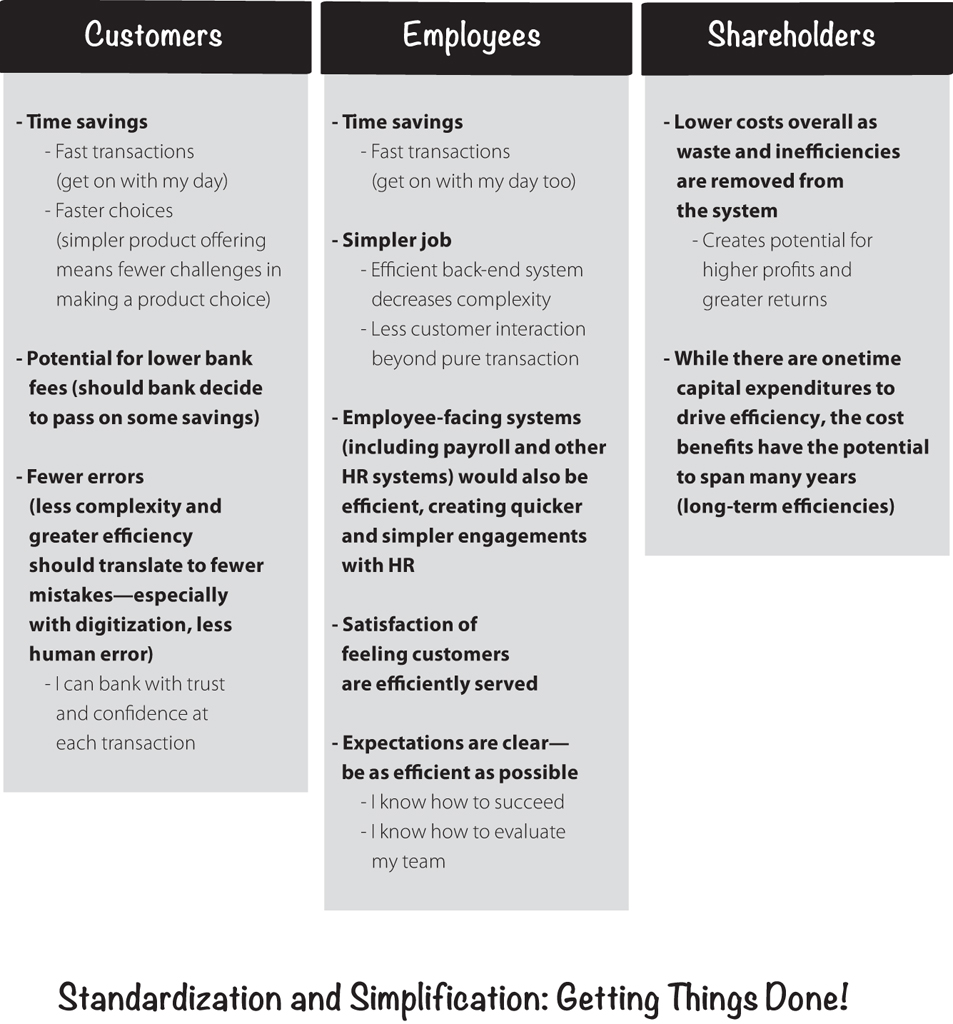

For the P&G category team, it was important to consider not just how they would benefit, but also to consider the retailer and the end consumer. For the bank’s challenge with efficiency and customer service, we might consider customers, employees, and shareholders. For the autism services provider, we might consider the families it serves to be one player, the support workers to be another, and the broader community of taxpayers to be the third player. If we believe that models might work in very different ways for the children with autism as opposed to their parents, we could break “families” into two different players. Or if we feel that it is vital to include the government, the direct funder of all the services, we might add it as well.

When it comes to identifying the players, three isn’t necessarily the magic number, but it does provide a good balance between getting enough diversity and avoiding too much complexity. The goal here is to get multiple perspectives and to build empathy for the players as you consider how the models work for them.

So, for each of the players, we ask how the model works for them—what benefits they get from it and how those benefits are produced. Often, the first benefits that come to mind will be more obvious or superficial, so it’s important to dig deeper, asking why each benefit matters and how it is produced, in order to build a robust picture of all the reasoning behind a model. Explore, as deeply as you can, what makes each model work and what is valuable about it.

The Pro/Pro Chart

One pro/pro chart (for the learning organization’s centralization versus decentralization dilemma) can be found in chapter 4 (figures 4-2 and 4-3). Here, figures 5-5 and 5-6 show what a pro/pro chart for the efficiency and customer experience banking dilemma might look like.

Here, you can see that in some cases, the initial benefit, such as the fact that customers will experience fewer errors under the efficiency model, is followed by a second point (in parentheses) that illustrates why that matters or how it works. In this case, fewer errors occur because the bank has reduced complexity and increased digitization, leading to fewer human errors. Ultimately, this could translate to greater confidence for the customer.

As you lay out the reasoning behind the models, give yourself time to reflect on them. If the answers don’t come quickly, try to see the models from the perspective of each player. Why might each one like this model? Remember the traps of your cognitive biases, and push yourself to acknowledge that not everyone values the same things that you value. You might like a job with greater scope to shape your own work; others might value and benefit from more direction from above. Consider, too, that even though some outcomes may not appeal to you, they might well appeal to others.

The key is to put yourself in the shoes of those players and identify what each model gives to them. If you feel stuck—and have reached the limits of your empathy—then stop what you’re doing and go talk to that player. Find real people from the stakeholder group, and ask them to help you articulate what they would get from each of the two models. In fact, this may well be a step worth doing, whether or not you feel stuck.

Try This

Working with a team, and including some helpful outsiders, can be useful in generating a robust list of the benefits for each player and the way the benefits work. Work on one model, player by player, pushing to get deeper into what is behind each model. Don’t stop working on that model until the team can genuinely muster enthusiasm for it. Even the health-care practitioners in Jennifer’s session on vaccines had to find a way to value what a model that does not mandate vaccinations might have to offer in terms of personal responsibility and informed choice. Once you feel the group has fallen in love, or at least in like, with the first model, move on to do the same task for the opposing model.

Remember, falling in love with the model doesn’t mean you will choose it. It just means you understand it deeply enough to see why someone would choose it. After you have reached that state for both of your opposing models, you can move on to the next stage (and the next chapter).

FOUR STEPS

To recap, this first phase of integrative thinking has four embedded steps.

Define the problem.

- – Articulate a problem worth solving.

- – Turn it into a “How might we?” question.

Identify two extreme and opposing answers to the problem.

- – Turn the problem into a two-sided choice.

- – Push the models to an extreme so that each represents a core idea.

Sketch the two opposing ideas.

- – Get clear about what each model is and is not.

Lay out the benefits of each model and the way it works.

- – Pick the most important players.

- – Create a pro/pro chart that captures your understanding of how each model works for the players.

Ultimately, integrative thinking is about leveraging the tension between models to create something new. So after you’ve articulated and considered the opposing models separately, the next step is to look at the models together, explicitly holding them in tension. The way you go about examining the models is the subject of the next chapter.

TEMPLATES

On the next few pages are templates you can use to document your work in defining the problem, selecting two opposing models, and describing the essential components of those models (figure 5-7); visualizing the models (figure 5-8); and crafting a pro/pro chart for the models (figures 5-9 and 5-10).