Chapter 7

Generating Possibilities

You can’t use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have. It is our shame and our loss when we discourage people from being creative. Too often creativity is smothered rather than nurtured. There has to be a climate in which new ways of thinking, perceiving, questioning are encouraged.

—MAYA ANGELOU

It’s hard to find many individuals who have had a greater impact on the way the world invests than Jack Bogle. Founder and former CEO of The Vanguard Group, an investment firm with more than $3.5 trillion in assets under management, Bogle dramatically changed his industry. He brought a new focus on costs to an industry obsessed with returns. He introduced the first index fund. He pioneered the no-load mutual fund. He was named by Fortune one of four investment giants of the twentieth century (along with Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch, and George Soros).

But before all that, Bogle was fired.

While still in his thirties, he had become the head of Wellington Management Company, which was then a leader in the business of managing and selling balanced mutual funds. These balanced funds, as their name suggests, had a broad portfolio of holdings, including largely conservative stocks and investment-grade bonds. When Bogle became CEO, Wellington Management was facing a crisis: with the emergence of more speculative (read: higher risk, higher return) equity funds, investors were losing their taste for stodgy, traditional balanced funds.

Bogle recalled this time in an essay marking his sixty-fifth anniversary in the mutual fund industry: “We could only watch helplessly as the balanced fund share of industry sales fell from a high of 40% in 1955 to 17% in 1965 to 5% by 1970.”1 Pressured to embrace the “go-go” philosophy of the era, Bogle arranged a merger with Thorndike, Doran, Paine and Lewis, a small Boston firm. Bogle agreed to give his new partners the largest share of Wellington’s voting control in exchange for an aggressive equity fund. The idea was to build a broader, stronger foundation for growth. Bogle was named CEO of the combined firm.

By 1974, the great bear market had taken its toll on the aggressive speculative funds. The go-go funds fell faster and further than the S&P 500, which itself was down almost 50 percent.2 Wellington Management was hit hard: assets fell from $2.6 billion to $1.4 billion, the stock price dropped from $50 per share in 1968 to less than $10 at the beginning of 1974. Finally, the aggressive money managers Bogle had brought into the firm had him fired as CEO of Wellington Management on January 23, 1974.

By chance, Bogle had a meeting the next morning with the board of the Wellington funds. A complex organizational structure meant that management and oversight of the funds were separate from management and oversight of the management company. Bogle had been CEO of both Wellington Management and the Wellington funds. He had been fired from the management company. He remained, at least overnight, the CEO of the funds. Exhausted and more than a little angry, Bogle made a last-ditch effort to stay on as CEO of the Wellington funds. His initial proposal—that the funds acquire all of the mutual fund activities from the management company—proved a touch too radical for that day. But he was kept on as CEO of the Wellington funds and was able to convince the board to create a new subsidiary, owned by the funds and solely responsible for their administration.

The subsidiary was directed not to engage in investment management, marketing, and distribution; Wellington Management would continue to perform those tasks. It was an absurd arrangement. “I was very honest with myself; there’s no point in starting an administrative company that doesn’t control investment management or distribution. Yet we had an understanding that I would not do either. But I figured we could work around that,” he says with a chuckle.3

First, Bogle had to come to grips with his situation. He did not want to run a hamstrung, administration-only shell of a firm, and he knew he could not simply ignore the terms of the agreement to engage in traditional fund management. He needed a new solution, and part of reaching it was to address a fundamental tension he saw at the heart of the investment industry: a choice between operating on behalf of the management company’s shareholders (as most firms did, charging high fees regardless of return) and operating on behalf of the fund’s customers (which Peter Drucker had noted was the only appropriate reason for a company to exist). This tension is not unique to Bogle’s context; it is a tension that pervades the modern corporate world and that Roger wrote about at length in his 2011 book Fixing the Game.4

Bogle had long loved the notion that the mutual fund customer should be the driving force of the industry. In his senior thesis as a Princeton undergraduate, he wrote that mutual funds should “serve their [customers] in the most efficient, honest and economical way possible.”5 But he recognized that in the prevailing construct, the mutual fund customer was often a pawn. The management company’s shareholders held all the power. Through the investment management and distribution fees it charged the fund, the management company earned a sizable portion of a fund’s investment return. The returns went to shareholders of the management company rather than to customers of the funds.

In his new subsidiary, Bogle decided to double down on the customer model, making the customer more central than ever before. He did so by changing the structure of ownership. Rather than accept the prevailing structure of shareholders and customers, he used mutualization to turn his fund customers into the ultimate owners of his firm. (For those not familiar with the term, mutualization is a process by which a company previously owned by shareholders changes its legal form to become a mutual company or cooperative in which the majority of the stock is owned by customers.)

Bogle mutualized his subsidiary and then stripped down the management apparatus and fees to ensure that he could maximize the total benefit to customers. He did so, he says, because “I’d been concerned about the industry structure for a long, long time . . . No man can serve two masters.” Bogle picked the master he wanted to serve—the fund customer—and created a structure that would allow him to do so.

THE BIRTH OF THE INDEX FUND

The key leverage point in Bogle’s solution, it turned out, was the index fund. Remember, Bogle’s new entity was prohibited from actually managing funds. Luckily, as he happily notes, “[An index] fund isn’t managed!” As you may know, an index fund holds stocks in the exact proportion of a major stock market index, most typically the broad-based S&P 500. If constructed properly, the index fund simply mimics how that part of the market performs, with no active management required. An index fund, Bogle says, would maximize value to the fund’s customers, because it could be run at a very low cost. It was, he says, “a problem of simple arithmetic: gross return minus cost equals net return.” An index fund could deliver great net returns.

An index fund also had an important second advantage. Bogle explains: “I could see that the Achilles heel of the fund industry was having funds whose performance went way up and way down. And performance that varies a lot from the market wreaks havoc . . . Investors put money in when the fund is performing well, and they take it out when it’s performing ill. That’s the reason fund investors are so far behind even the inadequate investment returns earned by nearly all funds.” By trying to predict and time their investments to future fund outcomes, investors put themselves behind in terms of real returns. What an index fund provides, Bogle argues, is a focus on the long term, complete diversification, rock-bottom costs, and relative predictability, in a way that can enable significant risk mitigation and accumulation of wealth by investors.

Index fund investors don’t have to fret about whether they’ve made the right choice of funds; all broad-market index funds track the market index. If the index fund is up, it is because the market is up, and not because the investor chose the right fund. If the index fund is down, it is because the market is down, and not because the investor chose the wrong fund. The prescription is to buy, hold, and wait, rather than shift from one managed fund to the next managed fund in search of the hottest manager and the greatest return.

Bogle’s first index fund was greeted with shrugs in some quarters and loud protests in others. Some even called it un-American. Yet it has proven to be remarkably successful. By 2016, it was estimated that as much as 20 percent of total US investment dollars were in index funds of some form, and Bogle’s little subsidiary, which he called Vanguard, is now the world’s largest mutual fund company—all this, thanks to Bogle’s willingness to take a leap on a creative new solution to a particular challenge in his industry (and some fast thinking on the night he was fired). To Bogle, looking back, the integrative answer was obvious. “I’m not talking about anything but common sense,” he demurs. That may well be true, but as Voltaire pointed out, “Common sense is not so common.”

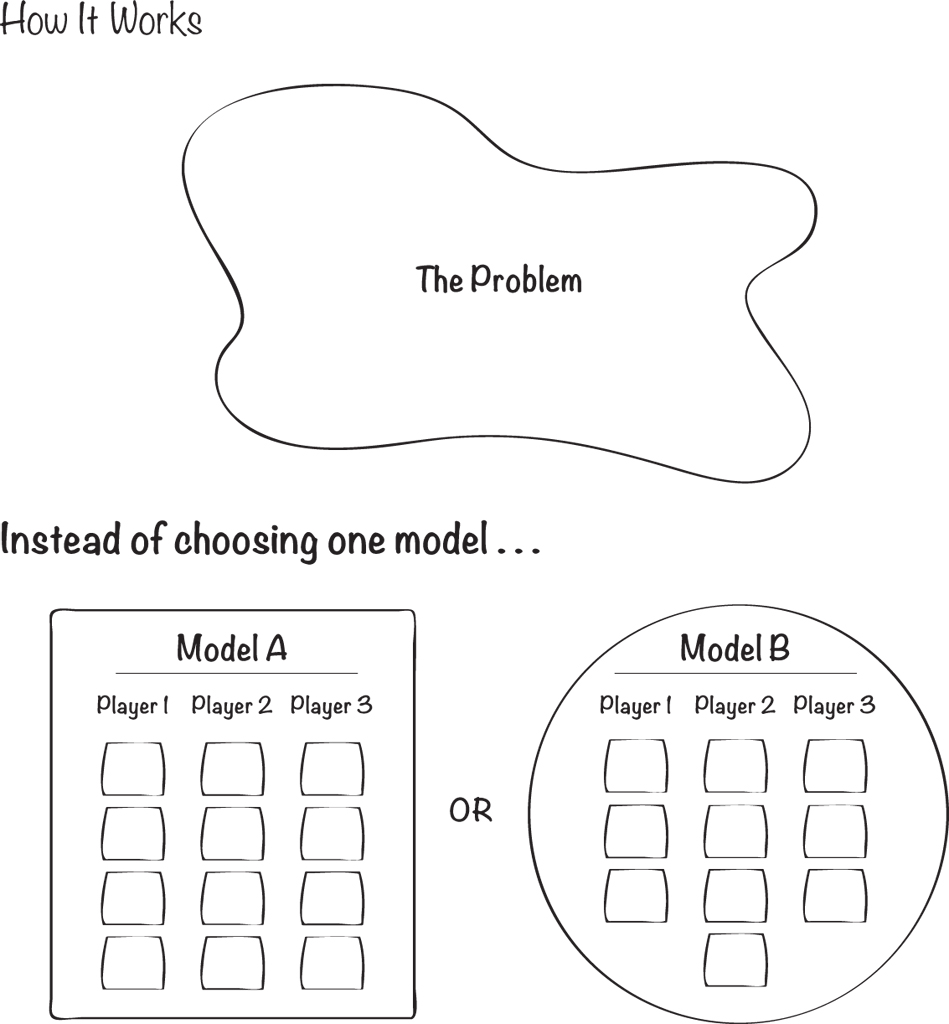

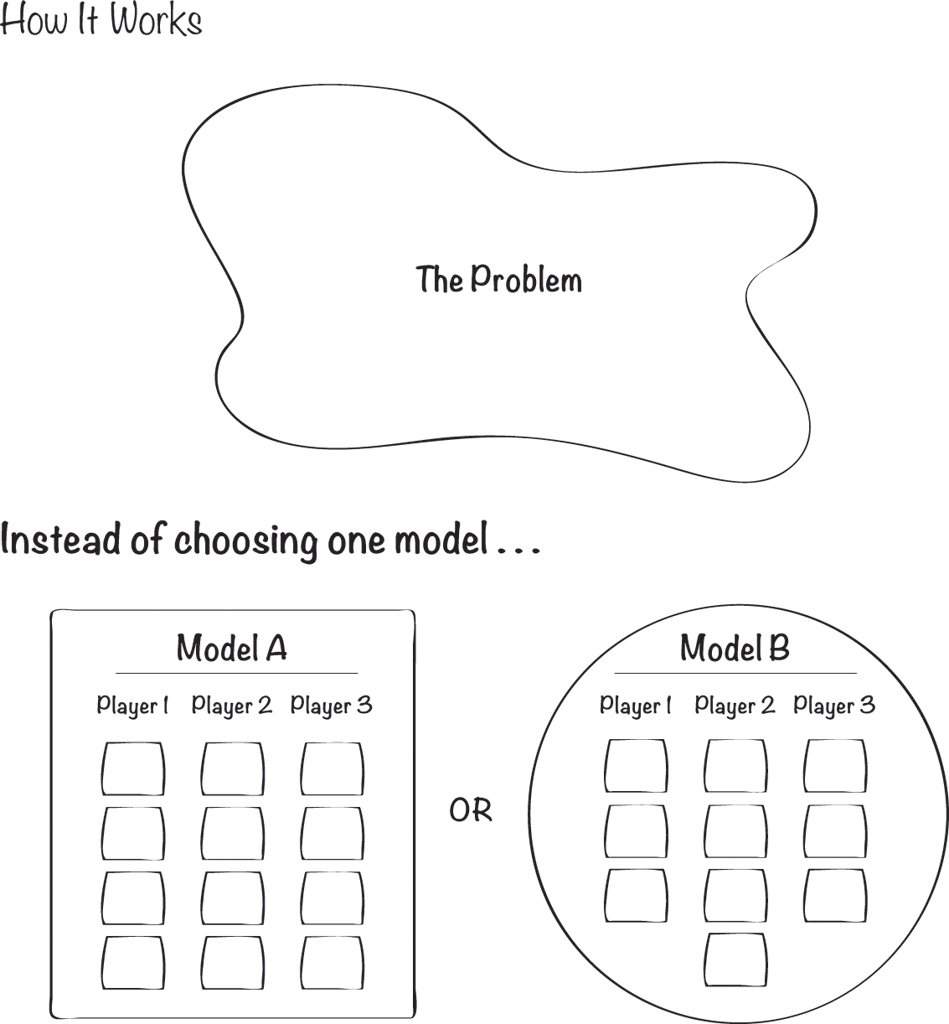

THREE PATHWAYS TO RESOLVE TENSION

Bogle’s approach to resolving the tension between prevailing models has much in common with the approach taken by Piers Handling at the Festival of Festivals. Each man used his rich understanding of the causal forces at play in his industry to think through a better answer, to integrate the model he loved with a key benefit of the opposing model. This, it turns out, is one of three pathways to integration that can help resolve the tension of opposing models.

We worked out these three pathways in response to our own frustration. In the early days of teaching integrative thinking, after encouraging practitioners to articulate opposing models and then deeply examine them, we had little in the way of advice for the next stage. Although we had lots of general tips about brainstorming and setting up the conditions for creativity, when it came to the process of actually creating a superior answer, we didn’t have much to say. Mainly we told practitioners to think hard until they found an integrative answer. If this was unsatisfying to us, you can imagine how our students felt about it.

So we set out to understand how the folks who had come to integrative answers had done it. Was there a particular way they went about resolving the tension? Was there a pattern to be found in the answer they created? We looked back over all the examples of integrative thinking from Roger’s initial interviews and from our students.

As we did, we found three types of integrations that roughly map to the three conditions and the three critical questions we laid out in chapter 6. These types of integrations may not be the only paths to creative resolution. In fact, we hope that others may be found going forward. But these three pathways represent our best current advice for this stage of the process. They are three directions in which you can start looking for an integrative answer.

To make the pathways easier to remember, we gave each pathway its own name: the hidden gem, the double down, and the decomposition. Here we explain each in turn, using an example to illustrate what each pathway looks like in practice. We begin with the hidden gem and with a spot of tennis.

PATHWAY 1: THE HIDDEN GEM

Tennis isn’t traditionally the sport people think of when they think of Canada. Canadian kids grow up at the hockey rink rather than on the tennis court. Or so it was in 2005. At the time, Canada was all but irrelevant on the global tennis scene. In men’s singles, Canada hadn’t had a top-fifty player for more than twenty years; it had never had a top-ten player. The women’s side wasn’t much better, with only three players in the top fifty since 1985, and only one in the top ten. Compare that record with that of US tennis, which in 2005 alone had two men in the top ten in the world, and three women in the top eleven, including the world number 1.

Moreover, Canadian players had never made the singles final of a Grand Slam tournament, and only one Canadian had even made a semifinal—Carling Bassett in 1984. There has been only one sustained bright spot for Canadian tennis: Daniel Nestor, who won more than ninety doubles titles, including eight Grand Slams. But Nestor’s success had proven to be more aberration than building block.

From a business point of view, Tennis Canada, the sport’s national federation, was in a similar state of defeat. The organization had taken on an $18 million debt to upgrade its stadium in Toronto, but only after the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) insisted it do so or risk losing the right to host a Masters-level tournament. The debt load, coupled with its relatively modest revenue sources, meant that Tennis Canada had only $3 million per year to spend on developing its players. In stark contrast, the US, French, Australian, and British tennis federations routinely garnered many times that amount from their Grand Slam events (the US Open, the French Open, the Australian Open, and the Wimbledon Championship—the four most important and profitable tennis tournaments in the world). The Grand Slams gave these four nations far more to spend on tennis development than Tennis Canada could ever hope to have at its disposal.

Two Opposing Systems

Against this bleak backdrop, the board of Tennis Canada decided that it was time for Canada to stop accepting stultifying mediocrity and instead become a consistently leading tennis nation. The push began with new board chair Jack Graham, new CEO Michael Downey, and two new board members who would go on to succeed Graham as chair: Tony Eames and Roger Martin (yes, the Roger Martin who coauthored this book). This group explicitly set out to find a new answer and turned its attention to two countries that, along with Russia and Switzerland, had been most successful in producing leading players over the previous twenty-five years: France and the United States. The tennis development models in those two nations represented thoughtfully constructed, broadly influential, and highly opposing approaches. France, on the one hand, had a strictly defined, highly standardized, centralized high-performance development program. Junior players who demonstrated an ability and a desire to win were funneled into the French Federation of Tennis system at a very young age. From that point onward, the French system controlled their tennis lives, including the location and nature of training.

The United States Tennis Association (USTA), in contrast, operated in a customizable, decentralized, and characteristically American way. It let many flowers bloom, leaving early-stage development to dedicated individuals, and especially to large-scale, for-profit tennis development academies such as the Bollettieri and Saddlebrook academies. At the time, the USTA simply waited for the talented, self-funded, and academy-trained players to rise to the top of the junior heap. When they did, the players would get money, training, and other resources to continue their development in whatever model and location worked best for them.

Both systems had produced a stream of winning players, but neither could easily be replicated in Canada. Tennis Canada had a fraction of the players, courts, and financial resources of its two competitors. Nonetheless, the board saw that there was something essential to love about each of the opposing systems. They came to deeply value the control of the French system. Centralizing the development of players created a constancy of purpose and strong adherence to a plan for success. In the American system, the most valued benefit was customization. Each US player followed a path to greatness that was specific to what that player needed. Some were nurtured by a driven parent, others grew up at a world-famous academy, and still others worked one-on-one with star coaches. To a great extent, each player charted her own course, creating a strong sense of personal ownership and accountability for success.

The Best of the Two Models

The French and American systems had between them many inherent tensions related to structure and mindset. It is hard to imagine being highly centralized and highly decentralized at the same time. But the key benefits of each model—control that drives consistency of purpose, and customization that drives a sense of personal ownership—are not so incommensurable. Might it be possible to build a new tennis development model that started from these twin notions and threw away the rest of the opposing models? That is what Tennis Canada did, building a new model that leveraged the idea of opportunity to get the best of control and customization in very different ways.

Under the new model, talented youngsters are identified and invited to be part of a staged development program, as they are in France. But Tennis Canada’s program is structured in a much more fluid, customizable, and decentralized way. Identified players younger than fourteen are given access to one of three national training programs, depending on where they live. Periodic weekend training programs are designed to supplement a child’s local club programs and personal coaching. These national training weekends offer elite competition and information on nutrition, fitness, strategy, and so on.

The weekends enable Tennis Canada to identify and nurture promising athletes without taking full control (and paying the full cost) of their development, in the way the French federation would do. The aim is to locally identify Canadian kids who have the potential for greatness and to help them on that path by giving them access to high-caliber competition and truly world-class coaches, hired from around the world. All the while, control of a child’s development rests largely in his own hands.

As players begin to compete on the junior circuit, they can transition to the National Tennis Center in Montreal. There, players between the ages of fourteen and seventeen participate in a full-time program under Louis Borfiga, former head of the French federation’s junior national training center. Borfiga’s program is aimed at honing technical, physical, and tactical fundamentals and providing top-level international competitive experiences at the stage when it is most impactful—just before a player turns pro.

But even as players reach the National Tennis Center stage, the model is not one-size-fits-all, control-at-any-cost. The Tennis Canada Performance Standard Fund enables elite athletes to opt out of the National Tennis Center to work with the coach and program best suited to the athlete, anywhere in the world—and still retain their funding and support.

Canada’s new model is unique in the world. It begins from two core principles: control and customization. Rather than simply say it would do both, Tennis Canada designed a purpose-built model that embeds the two principles in every development stage, while throwing away the rest of the existing models for high-performance development.

And the results? On ESPN’s 2016 Wimbledon broadcast, John McEnroe wondered aloud, “Who would have thought Canada would become a tennis superpower?” Canada’s Milos Raonic, then ranked number 7 in the world, was about to play in the men’s final. Eugenie Bouchard, another beneficiary of Tennis Canada’s new integrative strategy, had made the Wimbledon women’s final two years earlier, ranking as high as number 5 in the world. Behind Raonic and Bouchard, a roster of Canadian youngsters stand ready to move on to the world stage. Even though Tennis Canada still has only a fraction of the resources of other federations, it has figured out how to invest those resources in a way that has turned Canada into a truly competitive tennis nation.

Making Two Elements Work Together

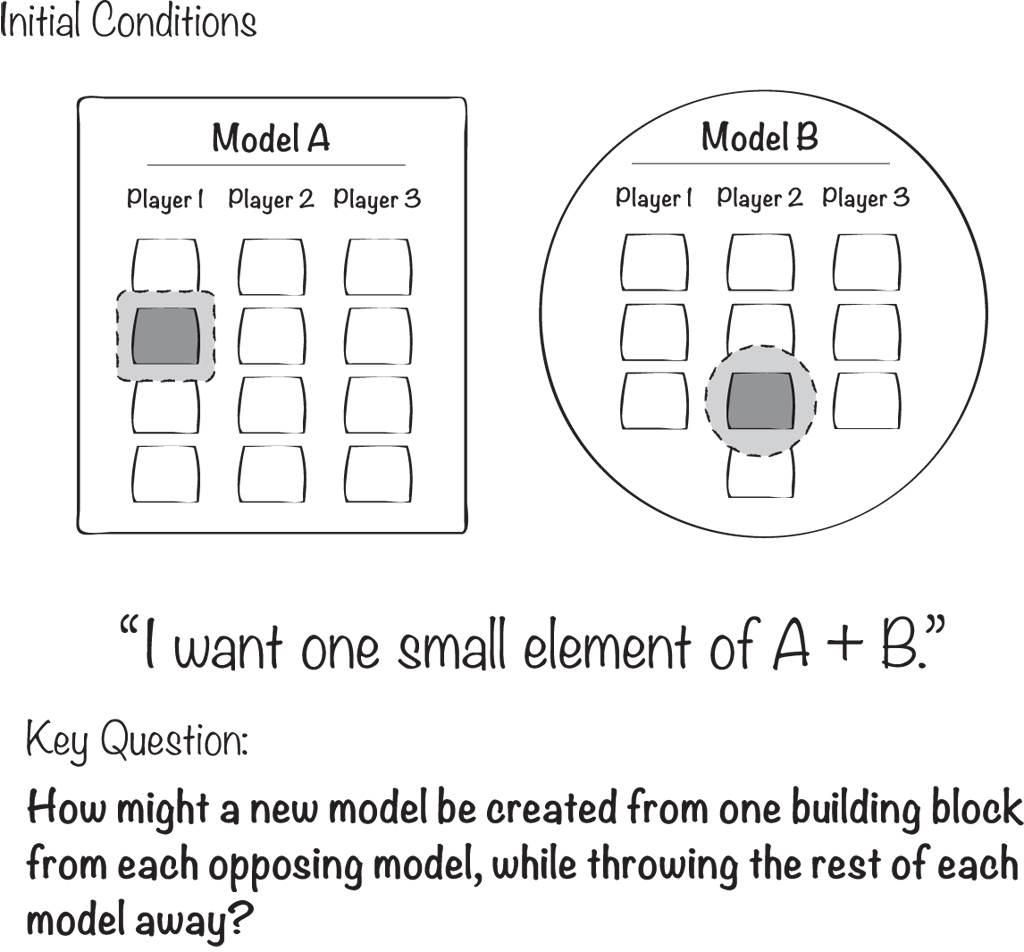

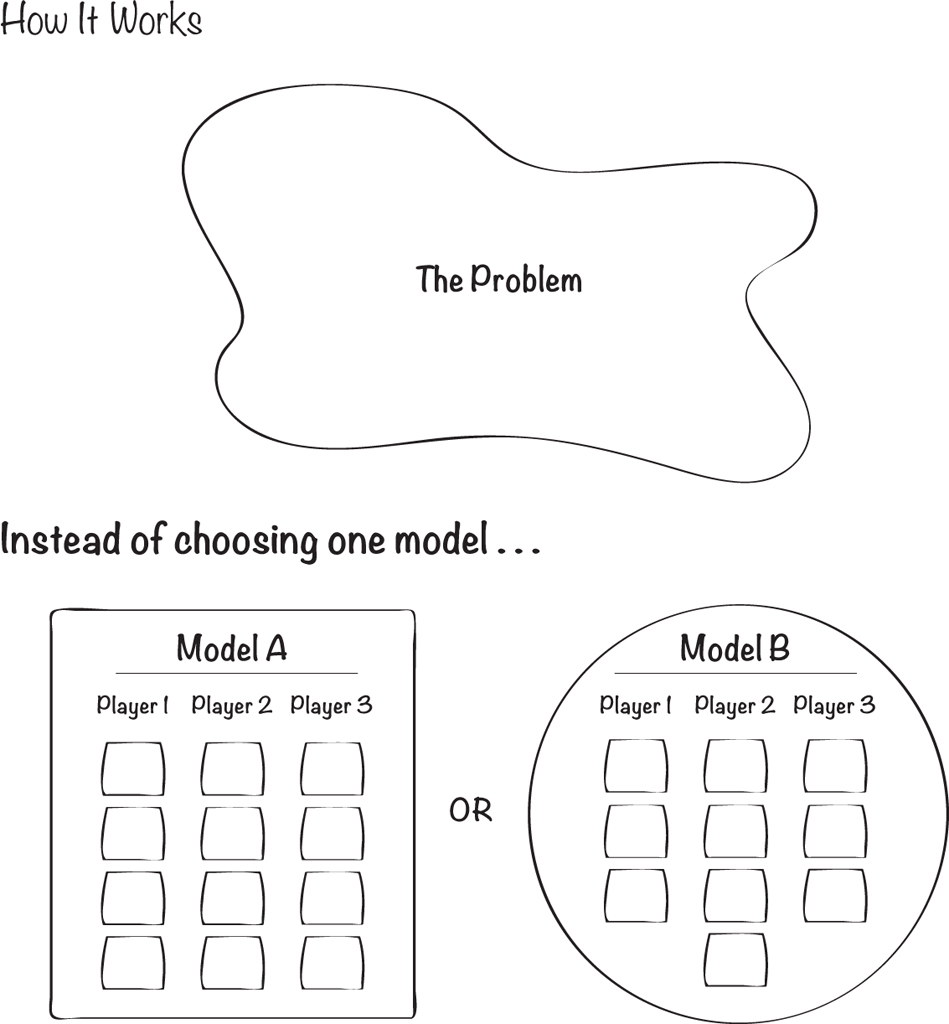

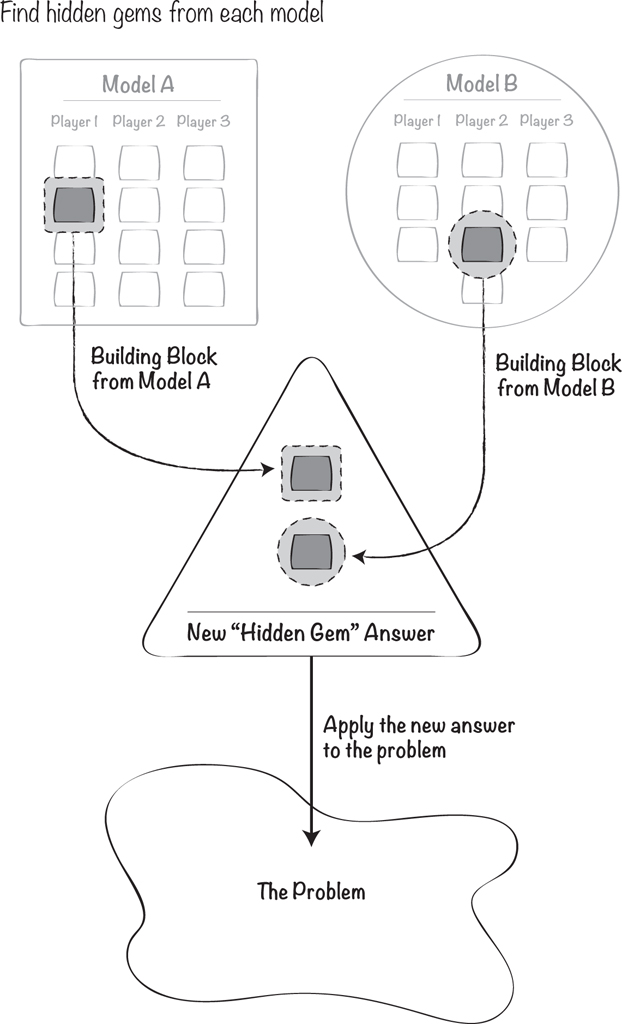

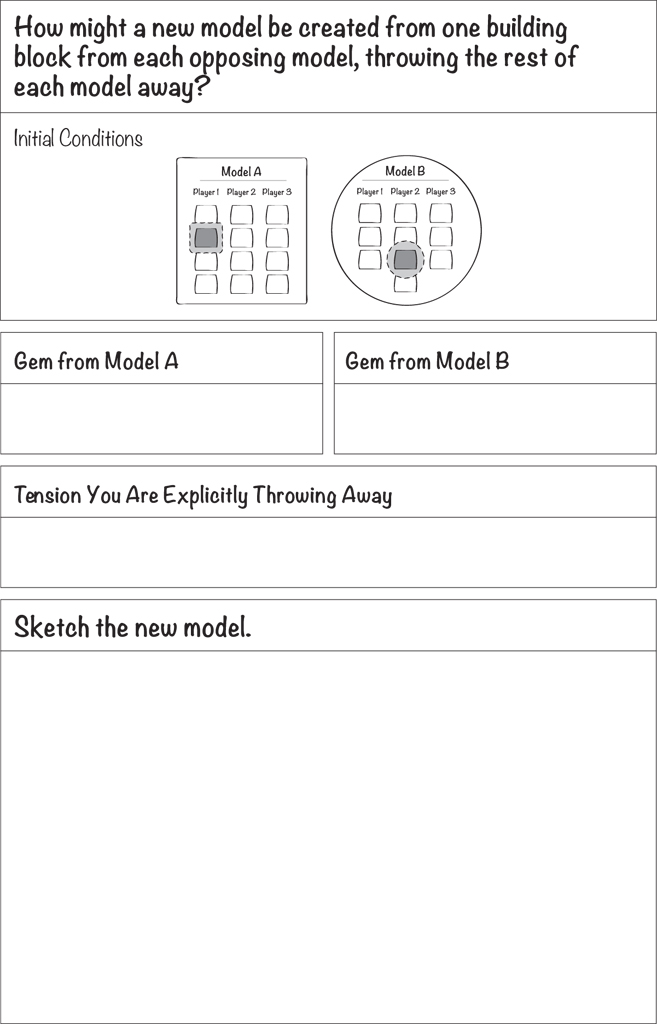

At the heart of Tennis Canada’s approach are two gems, one plucked from each of the dominant opposing models. The challenge for Tennis Canada was to make these two elements work together in a new and inspired way. This is the hidden gem approach. In this pathway, you take one nugget—one deeply valued benefit—from each of the opposing models and throw away the rest of the existing models. Using the two benefits as the core components of a new model, you imagine a new approach designed around the two gems.

In the hidden gem pathway, typically the key is to consider the inherent tensions of the model. To find a leverage point and integrate between the two models, you need to understand what points of tension make it untenable to integrate the models in the current context. When you understand that, you can explore how you might create a great integrated choice if you were to throw away those points of tension. For Tennis Canada, this meant building a system around control and customization but eliminating most of the structures that produce those outcomes in France and the United States.

The Tennis Canada example illustrates one successful implementation of a hidden gem integration. And, as is the case with each of the pathways, the starting point for the integration is a question. The question you ask to search for a hidden gem integration is this: How could we create a new model from our most valued building block from each opposing model, while discarding the rest of each model? To see how to visualize a hidden gem integration, have a look at figures 7-1 and 7-2.

Try This

There are many possible hidden gem integrations for any given choice, depending on which benefits you most value from the models, what you do with those core elements, and what new elements you introduce in your creative resolution. The key to creating a hidden gem integration is to ensure that the two benefits you choose are not in direct tension with one another. In this approach, you’re seeking benefits that are not incommensurable and that allow you to throw away the elements that are in tension. This means that your new model will by necessity have many new components; you’ll need to replace all the elements you’re throwing away with something new. A lot of creativity—imagining new ways to create the benefits you seek—will be required. You’ll need to try a few different combinations and prototype them, rather than settle on any one solution too early.

PATHWAY 2: THE DOUBLE DOWN

In the card game blackjack (or twenty-one), a player who doubles her bet on a favorable hand is said to be doubling down. Here’s how it works: after two cards have been dealt, a player has the option to double her initial bet, and in exchange the player receives only one additional card. In the simplest terms, this bet makes sense when the player has been dealt cards whose values add up to 9, 10, or 11. In that situation, she is well positioned to get close to (but not greater than) the desired count of 21 with one additional face card. In doubling down, the player is placing an extra bet on a potentially good hand, hoping that the one additional card she gets in return will turn it into a great one.

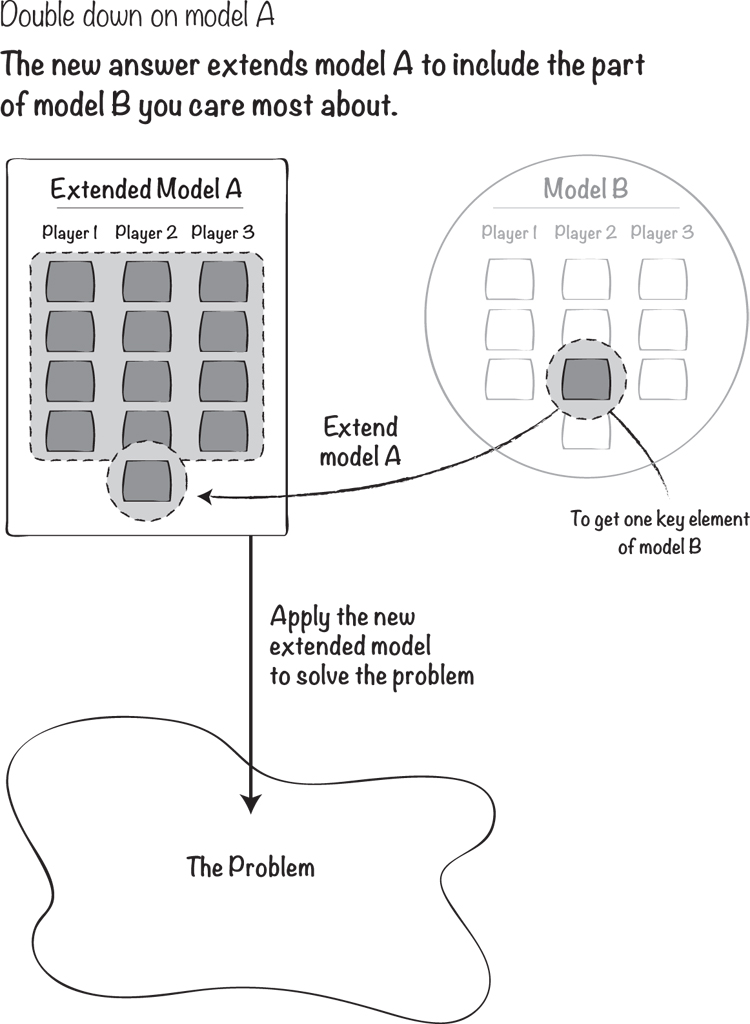

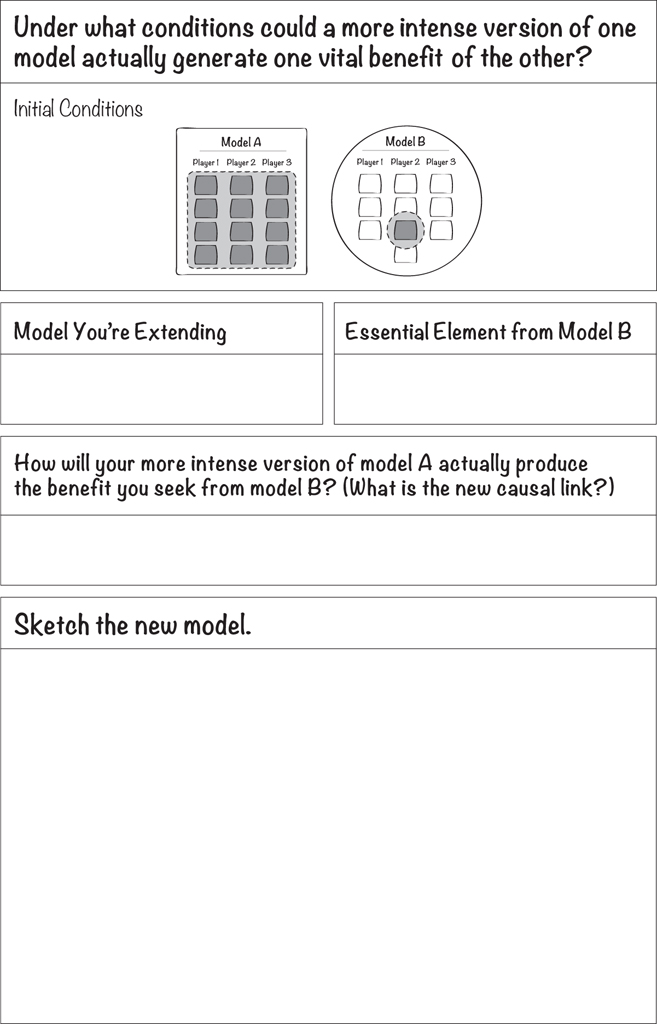

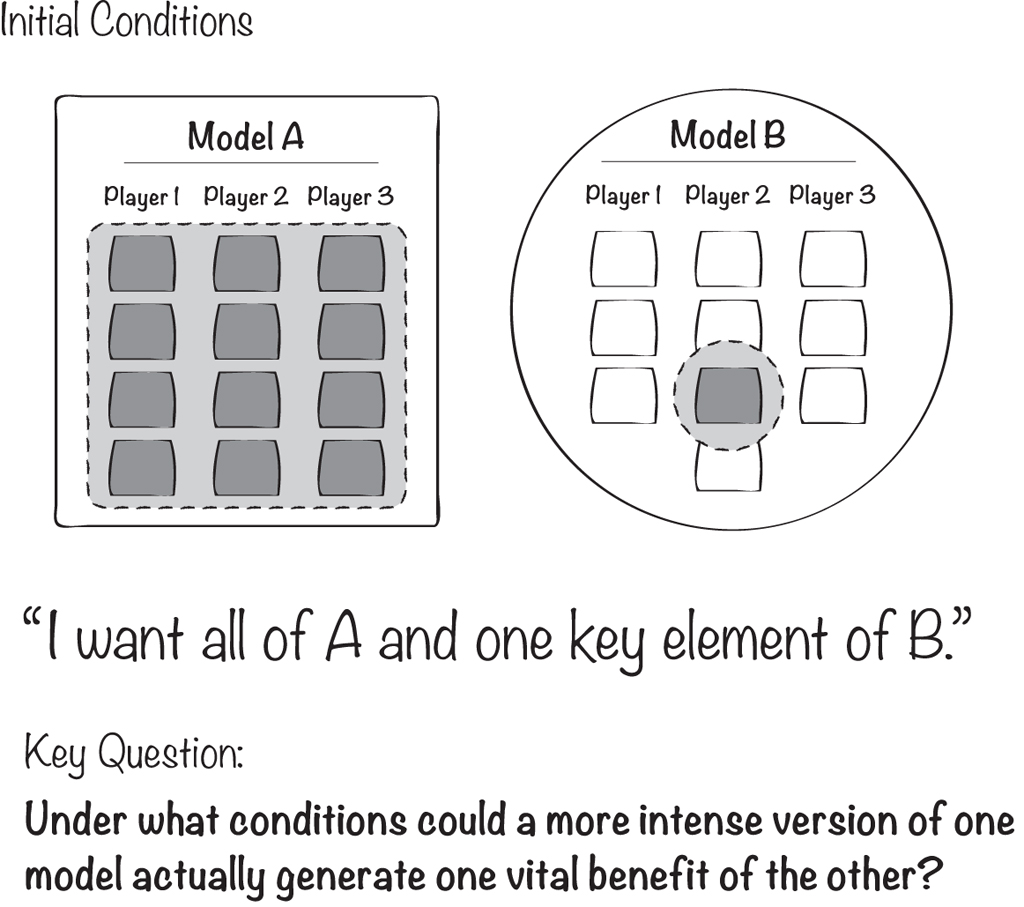

In our context, the favorable hand you’re betting on is one of the two opposing models you’ve created: the model that has many benefits you value. For Piers Handling at the Festival of Festivals, this was the inclusive community festival model; for Jack Bogle, it was the customer-driven firm model. In each case, the extra card that comes along with the bet is the one benefit you value most from the opposing model. To double down, you increase your bet on your favored model, actually extending or intensifying the model you like most, in such a way that you get one important benefit from the opposing model.

At the Festival of Festivals, this meant betting on inclusivity in order to get buzz. Handling added a people’s prize to make his festival more inclusive and, in doing so, generated a tremendous amount of media attention and word of mouth. At Vanguard, doubling down meant betting on customer-centricity in order to increase net returns. Bogle used a low-cost index fund to make his company even more customer-centered and, at the same time, to deliver even greater long-term returns. Both Handling and Bogle dumped overboard almost all features of the nonfavored model in a clever move to get the one thing they wanted from that opposing model.

In a double down, causality is key. To find a leverage point and integrate between the two models, you need to identify a model you truly love but that is missing one critical element. It is missing something important, and this missing element is what prevents you from simply choosing this model outright (remember, without buzz, the Festival of Festivals was unsustainable). Once you understand your favored model and have identified the one important missing benefit from the opposing model, you need to understand how that single benefit is produced in its current context. You need also to imagine how that single benefit might be produced in a new way, under different conditions, in an extended version of your favored model (a more inclusive festival or a more customer-centered investment fund). Causal modeling is often a key tool to help generate answers in this approach.

As with a hidden gem, the search for a double down begins with a question. The question you ask here is, Under what conditions could a more intense version of one model actually generate one vital benefit of the other? See a visualization of this approach in figures 7-3 and 7-4.

Figure 7-3. Starting Point for a Double Down

Try This

The double down integration is best used when you have initial conditions that favor it—when you truly love one model and value one vital benefit of the other. But as a search mechanism, you can use this approach whether or not these initial conditions exist. To push your thinking, ask how you might extend one model to get a core benefit of the other, no matter how you feel about the two models. Think carefully about what could cause your extended model to produce that desired benefit; what would you have to leverage in a new way? Explore what you would have to do differently to make this new integrated double down model work.

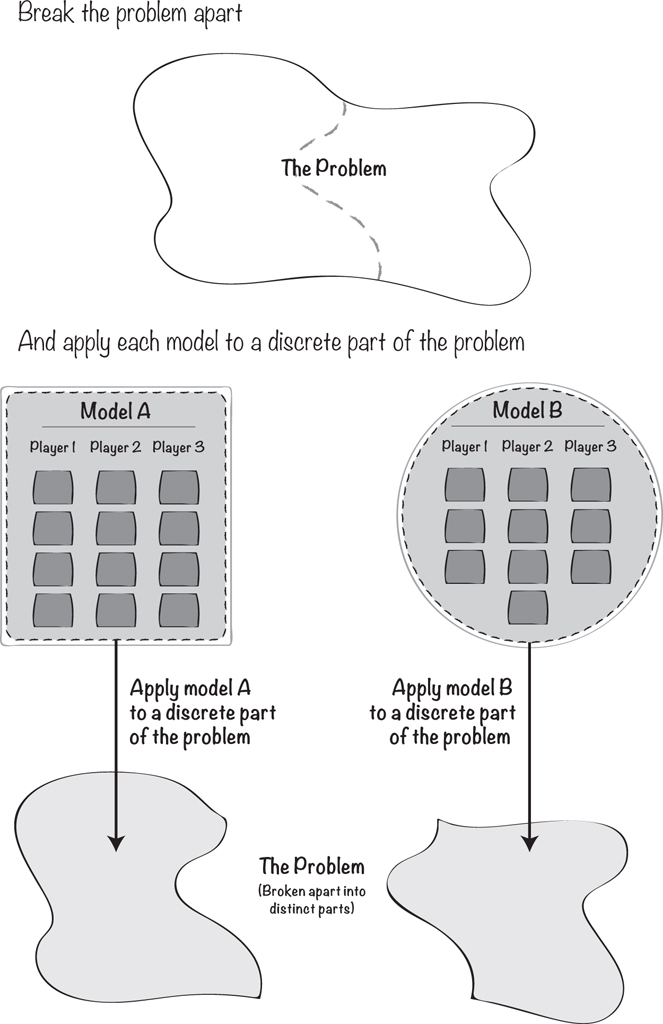

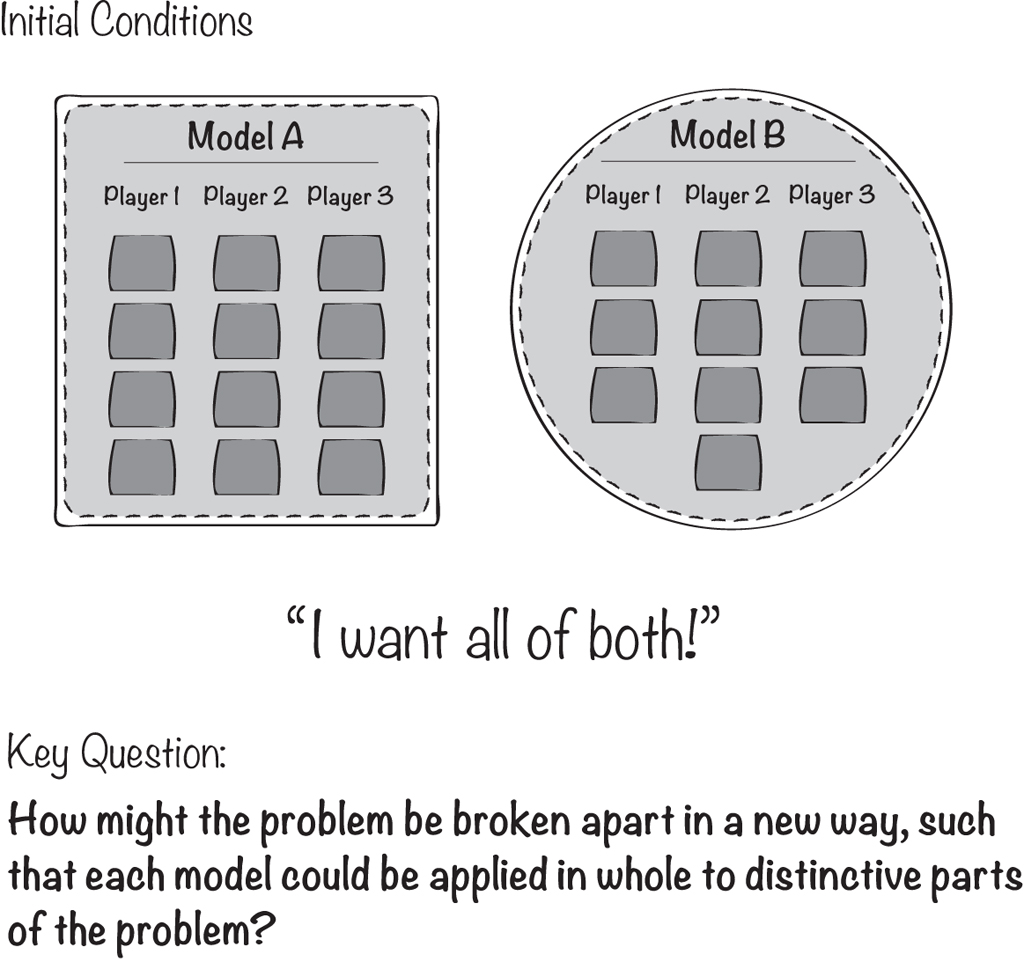

PATHWAY 3: DECOMPOSITION

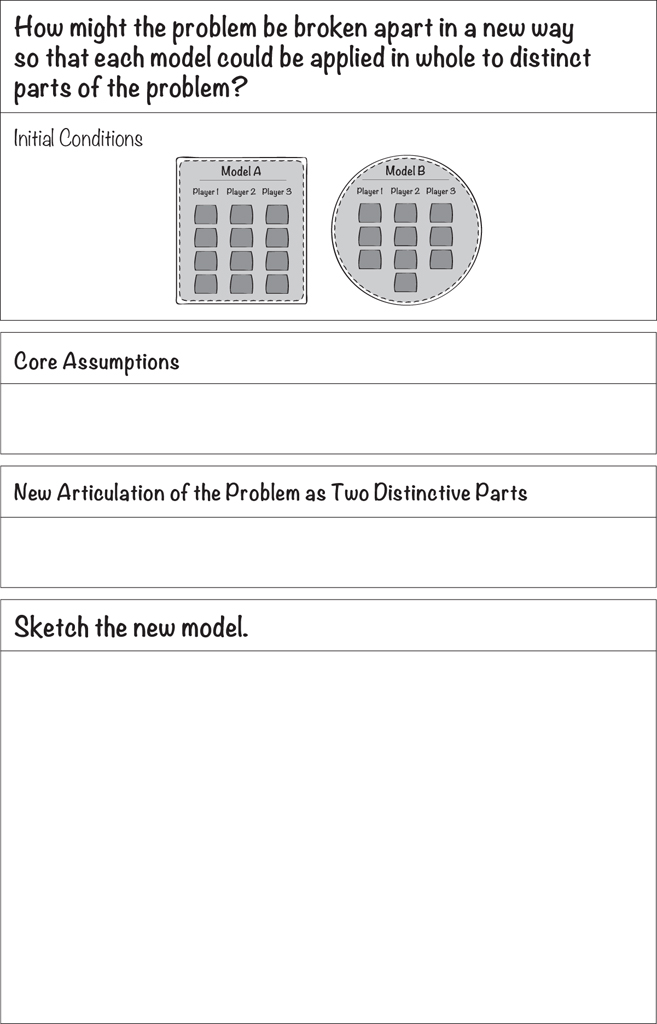

The third pathway to integration is conceptually different from the first two approaches. In both the hidden gem and the double down, you’re working to find new ways to combine the opposing models into a single new model that effectively solves the problem you’ve identified. In both cases, you mix and match elements of the models and also throw a good deal away. In the third approach, decomposition, you actually keep all or most of the existing models. The key to doing so productively is to reach a different understanding of the problem you’re trying to solve.

Sometimes you’re faced with two models that are both attractive, or two models you wish could be implemented at the same time, but you can’t see how it is possible. In this context, the challenge is to do two contradictory things at once. The strong temptation is to shrug, put your head down, and hope for the best when you tell the organization to do both.

Jennifer saw this in spades in a project she conducted with our colleague Darren Karn. The client was a police force interested in bringing integrative thinking into its training programs. At the outset, we conducted a series of interviews with current and former leaders, not only to better understand the organization but also to identify potential stories and challenges we could use in the training modules. We found that a key question for the organization was one that vexes all police forces to some degree: Should officers define their job as serving the community, or should the focus be on enforcing the law? In this case, everyone agreed that the organization should do both—but its leaders struggled repeatedly with the fundamental conflicts that emerged when officers tried to strike the balance day to day, case by case. The opportunity for the organization was to push past the premise that it needed to simply “do both” to understanding how it could do both more effectively than choosing either one. Without answering that question, the organization was asking officers to find a balance on their own. The whole added up to less than a sum of its parts.

To achieve a creative resolution of the tension in cases like these, it’s important to think deeply about the problem itself, working to parse it so that each model can be applied in full to discrete and distinct parts of the problem. The process is still an integration and not a compromise, so it’s critical that this new model create more value than comes from simply saying, “Let’s do both” and hoping for the best.

We call this third pathway a decomposition, because you seek to decompose, or break apart, the problem space in a new way that lets you apply the existing opposing models separately, to discrete parts of the problem, without diminishing their impact or compromising between them.

Decomposing a Wicked Problem

Decomposition is the way architect Bruce Kuwabara, together with his colleagues at KPMB Architects and a larger integrated design team, tackled a wicked problem presented by Manitoba Hydro.

Manitoba Hydro is a power utility in the central Canadian province of Manitoba. The company provides electricity and natural gas to nearly a million customers. In 2002, Manitoba Hydro purchased Winnipeg Hydro (the utility that provided electric power to the province’s capital city) and, as a part of the deal, agreed to build a new head office in downtown Winnipeg. The plan was to consolidate nine suburban offices into a single headquarters for more than two thousand employees.

Rather than stick to standard operating procedures for designing a new building, the folks at Manitoba Hydro took a huge leap: inspired by a fact-finding trip to Europe, they began a formal integrated design process to explore how to create a building that would set a new standard for energy efficiency in North America. The goal was to reduce energy consumption by more than 60 percent while also achieving architectural excellence in design.

Normally, in any given design process, the architect is the lead. In this case, a multifunctional team was formed: the design architects (KPMB), the architects of record (Smith Carter Architects and Engineers, now known as Architecture49), energy engineers (Transsolar KlimaEngineering), building system engineers, cost estimators, and project construction manager (PCL Constructors Inc.). The group spent a year framing and reframing the problem through a formal, facilitated integrated design process.

The challenge was considerable. Kuwabara acknowledges that he was daunted when pitching for the project. He even admitted to the selection committee that he knew how to achieve a 50 percent energy reduction but had no idea how to reach the 60 percent target. “We went for the interviews and, frankly, we were outgunned by a lot of the European firms,” the architect says. “They just have deeper experience in sustainability, in high-performance, low-energy buildings.”6

Kuwabara needed to change the game if he hoped to win it. His idea? “I kind of shifted the terms of the discussion to a healthy workplace.” In shifting the discussion, Kuwabara (with his associate Luigi LaRocca) won his firm the job but created a complex integrative challenge. The project now had multiple goals, including these two:

To be a super-energy-efficient building

To be a healthy and supportive workplace

Unfortunately, as those of us who have worked in typical urban office buildings know, these two goals are often traded off against each other. Kuwabara explains the typical tension between energy efficiency and livability in urban office environments: “Class A office buildings, as we know them—like the buildings in downtown Toronto—are the dinosaurs of the future. Why are we designing buildings we know aren’t that responsive to climate? The North American standard is that you go into a Class A office building, it’s 72 degrees, no matter what’s happening outside. Meanwhile, people wear sweaters in the summer, and they wear t-shirts in the winter. Buildings are either overheated or too cold.” He goes on to highlight an office dweller’s central complaint: “Why is it that in high-rise buildings, if they’re residential, you can have a window that opens, but in an office building you can’t? It has to do with controlling that set point of 72-degree temperature.”

In the traditional paradigm, every step toward greater energy efficiency represents a trade-off against livability, and that can lead architects to create hermetically sealed, utilitarian environments that prioritize energy goals over the comfort of human beings. And if the integrated Manitoba Hydro building design team accepted that paradigm, no better answer was possible. But the team was resolute; it wanted a building that was at once brilliantly efficient and remarkably livable. To create such a building, the team had to question core assumptions about how buildings relate to their environment.

Efficiency and Livability

In many cases, we think of a building as providing shelter from the environment, as fighting against the outside when it is too hot or too cold. This is a particularly strong impulse in a place like Winnipeg. Temperatures in the prairie city range broadly between 10 degrees Fahrenheit in the winter months and 79 degrees Fahrenheit in the summertime.7 Of course, those are averages, and it wouldn’t be strange for the city to see days colder than minus 20 degrees Fahrenheit in winter and hotter than 85 degrees Fahrenheit in summer. In such conditions, the obvious impulse is to aggressively control a building’s climate through sophisticated heating and air-conditioning systems that seal it off from the outside environment. The underlying assumption? You need to shut out the outside world in order to make the inside world energy efficient.

Kuwabara wondered whether there was another way. Working closely with climate engineers Transsolar and the rest of the integrated design team, he found one. The leverage point was the city’s own climate. Winnipeg’s northern prairie location means that the city has an abundance of two things: sun and wind. In total, Winnipeg gets 2,300 hours of sunlight annually, and as much as 16 hours of sunlight each day during the summer. The winds sweep in, sometimes from the Arctic but also often from the south. Instead of thinking about how to control the climate of the building, the integrated design team asked how it might make the city’s climate work for the building, in turn producing both efficiency and liveability.

The integrative insight was to decompose elements of the building’s environment normally considered to be part of a single “building climate control” problem: HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning). Kuwabara and the team asked themselves, What if we separated the heating/cooling systems and the ventilation systems, driving efficiency hard in the heating and cooling, and liveability aggressively through ventilation?

Go with the Flow

Typically, 45 percent of the energy load in a building in this climate is tied to heating and air-conditioning (and another 25 percent to lighting). So it makes sense to focus on these dimensions when you’re seeking energy efficiency. Accordingly, the Manitoba Hydro building features a massive geothermic field: hundreds of holes drilled to a depth of four hundred feet below the building. Radiant water-based heating and cooling reside in the concrete slabs that support the building. The building has double walls and an outer envelope, a thermal-glazed glass exterior that produces a greenhouse effect to warm the building with the sun’s rays.

All these measures drive down the energy demands. But they could create a stifling environment without a new approach to ventilation—one that leverages the windiness of downtown Winnipeg (Kuwabara muses, “This is like a coastal city where the wind is always coming in from the ocean”). Rather than build traditional systems that would recycle forced air through a closed building, the team created a building that could breathe: “The tower has got three stacks of six floors, and each stack has a south-facing atrium,” Kuwabara says. “The atriums are very large and very wide; they take all the prevailing winds that come [through each base] . . . and they effectively become the lungs of the building. All the fresh air comes from outside to inside. It gets drawn naturally into the underfloor system and then rises as fresh air into the workplace, into every loft. It is drawn slowly, almost unnoticeably, to the north, where we have smaller atriums that pick up all this air and exhaust it into what we call a solar chimney.”

The flow works naturally, as the warm air (heated by the glass atriums) rises up and through the building. As Kuwabara explains, “It’s a natural passive system. Everything that we were doing in the workshops with the integrated design team was about how to maximize passive energy systems to create the best air quality. Unlike conventional buildings, we don’t recirculate any air. Our air comes in and goes out.” The aim was always to create a supportive, healthy platform for the people working in the building, while simultaneously reducing energy loads.

The building has a temperature range (rather than a firm set point) around 65 degrees Fahrenheit. It is designed to respond to the weather outside and to the people inside. “We said, ‘Listen, people aren’t stupid,’” Kuwabara explains. “‘They know how to control their own environment’ . . . [so] we created this living organism that individuals actually control on a daily basis.” The building allows users to open windows and control lighting.

The result? “Every system that we have is quite unconventional, so it ended up that we surpassed the sixty percent [goal]. Our total energy consumption is in the vicinity of ninety kilowatt hours per square meter per year. By comparison, many buildings are four hundred kilowatt hours per square meter per year, and even so-called energy-efficient buildings are two-eighty or two-seventy.”

And livability? The design of the spaces helped Manitoba Hydro build a more collaborative culture and a happier, healthier workforce than it had in its former quarters. “We reduced sick days 1.2 days per person, per year, over two thousand people,” Kuwabara says. “It’s not just productivity, but health.” Moreover, the building has won major international awards, has been called the most important building in Canada, and was even dubbed the “best office tower in North America.”8

This was a decomposition integration. Instead of accepting the existing problem frame—climate control—Kuwabara and the integrated design team questioned a fundamental assumption: the natural pairing of heating/cooling with ventilation. In doing so, the team broke the problem apart in a new way. This decomposition let the team create a new answer, producing a building that was at once more efficient and more livable than other buildings. The team was able to artfully combine two models that once seemed to be in strict conflict with one another.

Distinct Model Elements

A decomposition integration rests on your knowing when and how to apply each model to its best advantage. Rather than choose model A or model B to apply to the entire situation or at all times, you base a decomposition on applying the models together by carefully distinguishing when and how each can be applied to distinct elements of the problem space (see figure 7-5). Typically, this means seeing the problem space in a new way—breaking apart elements that are traditionally considered to be part of a whole (see figure 7-6).

Try This

Figure 7-5. Starting Point for a Decomposition

Coming to a decomposition integration demands a deep understanding of the context at hand. For a decomposition to work, there must be a meaningful dividing line in the problem—a way of breaking the problem space into two distinct parts, each of which responds well to one of the opposing models. Changing the understanding of the problem requires the team to delve into assumptions to identify the meaningful dividing line. Without a new understanding of the problem, if you try to simply “do both,” you are likely to find yourself struggling, constantly trying (and often failing) to balance opposing models in real time. You want to set a higher aspiration to create a new, great answer.

THINK CREATIVELY

The three types of integrations we have described (the hidden gem, the double down, and the decomposition) represent proven pathways to creative resolution. When you’re faced with an integrative challenge, instead of hoping for inspiration while staring at a blank piece of paper, start to generate ideas and envision prototypes by asking the three questions: How might a new model be created from one building block from each opposing model, throwing away the rest of each model? Under what conditions could a more intense version of one model actually generate one vital benefit of the other? How might the problem be broken apart in a new way so that each model could be applied in whole to distinct parts of the problem? These three questions can be applied, in turn, to any integrative challenge, helping you expand the set of possible solutions to be considered.

In the end, integrative thinking isn’t a one-size-fits-all proposition. Contexts differ greatly, and so do the answers appropriate to those contexts. The aim is to make sense of the opposing models in front of you and to apply the kind of integration best suited to those models, along with a dash of imagination. Our three pathways to integration represent a place to start; they are search mechanisms that can help you frame a discussion of possible creative resolutions to a given problem.

But any creative process also demands some ground rules. Otherwise, it is easy to get bogged down in minutia or spin off in unhelpful, random directions. To have a productive session around these three pathways, remember these core principles.

Use all three pathways as thought starters. Regardless of your initial conditions, don’t get too focused on one vector or one idea; keep going until you have generated multiple possibilities that could resolve the tension between the models and solve your problem. By all means, start with the pathway that is most closely aligned to your initial conditions. If you really do love one model more than the other, try finding a double down solution first. But then try out the others as well. If one of the pathways doesn’t yield an answer, that’s fine. The point is to ask the question and see what comes of it.

Defer judgment. At this stage, all ideas are good ideas. You can’t know where an idea might lead. And in integrative thinking, the creative solution is a productive combination of multiple ideas, each of which would be inadequate on its own. So turn off your natural instinct to judge ideas. Instead, capture all the ideas that are generated, and encourage individuals to share all the ideas that occur to them, even those that seem silly or off the point. You never know where those ideas might lead.

Build on the ideas of others. Simply put, more and better ideas will come out if the participants actually listen to one another. Often, group members have different levels of enthusiasm for the existing models, and different benefits they value from each. Listening to one another can help bridge these gaps. Our advice is to leverage individual, paired, and group brainstorming approaches to ensure you get a diverse set of ideas, and make clear that building on the ideas of others is an explicit goal of the process.

Following these basic principles can help individuals collaborate and make connections—two activities that are crucial to generating creative ideas in any context but especially in the integrative thinking process. Because you’re beginning with opposing models, some groups wind up with different factions in love with different models. The danger is that these factions will shut down the ideas that come from the other side. Using the pathways, deferring judgment, and building on the ideas of others can help teams avoid this trap.

Once you have potential integrative solutions on the table, the next stage is to think about how the ideas might be built out, explored, and tested. You are not yet ready to choose a single possibility and move on. Instead, you’ll take several possibilities to the next stage and assess these prototypes via testing and experimentation. Only after that will you feel confident enough to move ahead with an integrative answer.

TEMPLATES

We have created templates to help you organize your work as you follow the three pathways discussed in this chapter. Figure 7-7 guides you along the hidden gem pathway; figure 7-8, the double down pathway; and figure 7-9, the decomposition pathway.