Chapter 9

A Way of Being in the World

In 1887 Lever Brothers bought land in Cheshire, England, to build an expansion to its soap works. But CEO William Lever was interested in something more than a factory; he wanted to build a community. Over the next twenty years, he oversaw the construction of a custom-designed village featuring more than seven hundred homes spread across 120 acres, along with an art gallery, a hospital, schools, a concert hall, a swimming pool, and a church. Lever’s vision—dubbed Port Sunlight, after his top brand—was to create a model town for his workers, one where they could expand their minds through education, religion, and the arts.

The idea, he wrote, was to “to socialise and Christianise business relations and get back to that close family brotherhood that existed in the good old days of hand labor.”1 It would be good for his workers, he said, and it would be good for his business. Lever felt that healthy, happy employees would be productive, especially if they saw that their environment was tied to their own hard work. So he funded the village with company profits.

In 1903 some 10 percent of the company’s capital was invested in Port Sunlight. To Lever’s mind, it was the most effective form of profit sharing.

If I were to follow the usual mode of profit sharing, I would send my workmen and work girls to the cash office at the end of the year and say to them “You are going to receive £8 each; you have earned this money; it belongs to you. Take it and make whatever use you would like of it. Spend it in the public house; have a good spree at Christmas; do as you like with your money.” Instead of that I told them: “£8 is an amount which is soon spent, and it will not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets or fat geese for Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant, viz. nice houses, comfortable homes and healthy recreation.”2

If this sounds a tad paternalistic to the modern ear, keep in mind that many of Lever’s contemporaries felt no such impulse to better the lives of their workers—or if they did, they failed to act on it. Most industrial workers at the turn of the twentieth century lived in congested tenements, with poor sanitation and increasingly strained infrastructure. Disease and poverty were rampant. Port Sunlight must have seemed, to those willing to forgo their whisky and sweets, something of a utopia. And so, Port Sunlight sustained; until as late as the 1980s, all its residents were employees of Unilever, the global multinational created in a merger of Lever Brothers and a Dutch margarine manufacturer.

Lever’s legacy remains in the form of his model village but also in Unilever itself, now one of largest consumer goods companies in the world. The company has a stable of more than four hundred brands, including Dove, Becel, and Lipton, and earns revenues of €53 billion per year. CEO Paul Polman, a soft-spoken Dutchman who came to Unilever after a long career at P&G and a shorter stint at Nestlé, reflects fondly on Lever’s “own form of enlightened capitalism.”3

Polman has thought a great deal about enlightened capitalism. He joined Unilever in 2009 as its first-ever outside CEO, just as the global economy was entering the darkest days of the financial crisis. In that disruption, he saw an opportunity. “I’ve always been a little bit concerned about that dominance of the financial industry,” Polman explains. “It was very clear, to me at least, that the system that we were operating under had run its course—had done well for many people, there’s no question about it—but it had run its course. We needed a different business model.” Polman set out to create that new model.

He asked his team to think hard about what Lever had called “shared prosperity.” Before long, the company created the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan, a vision to decouple the company’s environmental footprint from its growth, meaning that the company would aim to grow its brands while simultaneously reducing its environmental impact. The goal was to move toward “a world in which everyone can live well and within the natural limits of the planet.”4 Importantly, under the plan, Unilever would assume responsibility for the whole of its supply chain “from farm to fork,” rather than outsource that responsibility.

TAKING A LONGER-TERM VIEW

At first blush, this might seem like a typical corporate social responsibility initiative. But Polman’s ambition extended far beyond traditional CSR, which he equates to “having a less negative footprint or doing some activities to make you feel good.” Instead, he says, “you really have to show that business activity has absolutely contributed to solving some of these issues.” The Sustainable Living Plan was only one of Unilever’s forays into solving, rather than paying lip service to, our toughest global challenges.

Another component of Polman’s new business model is a very different approach to investors. He had long been worried about the negative effect of short-term investing on the long-term health of companies. It is hard to overstate how short-term the capital markets have become over the past decade. As of 2015, the annual turnover rate for US stocks was slightly more than 300 percent. That amounts to an average holding period of only seventeen weeks. Exchange-traded funds—baskets of securities that trade like common stocks on an exchange—go even faster, with an estimated holding period of only twenty-nine days.5 It wasn’t always thus. According to Polman, “the average holding of a Unilever share in 1960 was 12 years; 15 years ago, it was about five years.”6

This shift to the short term means, by and large, that we aren’t so much investing as speculating. Jack Bogle has pointed out that this practice is bad for investors. Polman saw that it was also bad for business. Now, rather than grow the fundamentals of a business, CEOs are incentivized to boost the company’s stock price over the short run. This is a matter of increasing expectations rather than real returns, talking up the stock rather than improving the company.

Polman was determined to change the short-term focus at Unilever: “One of the things I had to do was to move the business to a longer-term plan,” he says. “We had become victims of chasing our own tail, cutting our internal spending in capital, R&D, or IT to reach the market expectations. We were developing our brand spends on a quarterly basis and not doing the right things, simply because the business was not performing. We were catering to the shorter-term shareholders. So I said, ‘We will stop quarterly reporting, and we will stop giving guidance.’”

When Polman announced Unilever’s new policies in 2009, the company’s shares dropped 8 percent. Yet he remained steadfast in his message to shareholders. “I explained to them we were going to run the business for the longer term. We were going to invest in capital spending. We were going to invest in training and development. We were going to invest in new IT systems. And we were going to invest back in our brand spending.” These investments would take time to pay off, and they had the potential to skew quarterly numbers dramatically. So Polman asked his shareholders to take a longer-term view, too.

Some shareholders were willing to take the leap with Polman; those who weren’t, sold their shares, an action that was fine with Polman. As he sees it, CEOs spend too much time trying to cater to current shareholders, a group almost impossible to fully satisfy. Because stocks are broadly held, shareholders tend to be a mixed lot, and, Polman muses, “they have totally different opinions. If you would run your business based on the input from all of your shareholders, you’d go berserk and you’d probably run your business into the ground.”

Instead of catering to the whims of an established base of short-term shareholders, Polman focused on getting the shareholder base he wanted—attracting the long-termers who valued growing real returns over inflating expectations. And the policy has worked: Unilever’s top fifty shareholders now have an average holding period of seven or more years.

The Double Down

Back when he was working out the plan, Polman was torn between wanting to take a long-term perspective and needing to adapt to the short-term focus on the capital markets. He saw that, by and large, a long-term focus is great for the business and the world; it provides room to invest, incorporates externalities, and spurs innovation. But a short-term focus is what the capital markets demand, including mandated quarterly reporting, in the name of discipline and accountability. A short-term focus has the potential to produce happier shareholders, too, because satisfying shareholders becomes the primary objective of the company.

Polman wanted the deliriously happy shareholders from the short-term model as well as the real, sustainable growth from the long-term model. But he couldn’t get both by acting as most CEOs do and simply accepting the trade-offs. Instead, he doubled down on the long-term model, using total transparency as the leverage point to produce happy shareholders. His new solution wasn’t about making his current shareholders happy; it was about attracting new shareholders who would be happy with a long-term orientation and sustainable growth.

As he explains, his solution depended on being very clear and unapologetic about the game plan: “Transparency builds trust . . . We spent a disproportionate amount of time explaining why a more socially responsible business model is actually also a better model for the shareholders longer term—if you are a long-term shareholder. We made it very clear to shareholders that this model would give them consistency of delivery, where every year we would grow faster than the market, where we would improve stability.” Polman was open about the fact that Unilever’s approach might not deliver the highest profitability every year, but he promised it would deliver consistently, year after year. And so it has.

His Job in the World

Polman, like many of the integrative thinkers we’ve met, tends to speak of his resolution of trade-offs matter-of-factly. Just as Jack Bogle described the notion of an index fund as “obvious,” Polman argues that his new business model was a relatively simple matter: “I’ve never actually believed in that trade-off [between the short term and the long term],” he says. He knew a better answer—better for Unilever and for the world—was required, and he set out to create it. Pressed on how he was able to overcome the trade-off while many of his peers have not, Polman is charmingly blunt: “I think it is a cop-out. Any CEO can decide that he shouldn’t get paid too much. Any CEO can decide to think long term, if you need to change things and you value change . . . I think it is courageous leadership that is missing. The excuse is that the market won’t let you. There are things the market obviously will not understand, and there are limitations. But we have a license that is much broader than any of the CEOs claim.”

In other words, Polman sees it as his job to create a great choice. And he argues that the task is well within his capabilities. This is Polman’s way of being in the world, his stance about how the world works. Stance, it turns out, is a crucial piece of the integrative thinking puzzle.

EXPLORING STANCE

In The Opposable Mind, Roger defined a stance as “how you see the world around you, but . . . also how you see yourself in that world.”7 Your stance is the sum total of your mental models about the world, an overarching frame of the world and your role in it. Our colleague Hilary Austen, in her study of artistry, uses the term directional knowledge to capture the same idea as stance, explaining that it contains both identity and motivation: who you are and what you are trying to do. She writes that directional knowledge “provides the orientation for practice . . . [It] is in large part tacit and deeply embedded. It rarely bears scrutiny except in times of transformational change within a personal practice.” Your stance, she argues, “is quietly developed and often taken for granted.”8

Your stance plays an important if little-examined role in your life. The stance you have about the world, and your role in the world, drives you to act in specific ways (and not in others). These actions then help determine your outcomes.

Two Chefs

How does stance affect actions? Consider two chefs. Both chefs have the same number of years of training and experience. They both have access to the same professional kitchen, the same ingredients, and the same tools. They also have the same notional intention: to make, say, a dish of braised veal. The only thing that separates them is their stance about what it means to be a chef.

One believes that food is love: the chef’s job, he believes, is to take the best ingredients available and prepare them with genuine affection for the ingredients and for his diners. The dish he produces is simple and delicious—a steaming, fragrant bowl presented without undue fuss.

The second chef has a different stance. She believes that food is art and that we feast first with our eyes. Her job, then, is to make her dish not only taste wonderful but also look beautiful. Her dish is presented with precision and flair, carefully constructed and delicately placed just so.

These chefs’ dishes could not look more different. The diners’ experience of them is different as well, despite the same ingredients, tools, and intention. It is the stance of each chef that drives these very different outcomes.

Stanford education professor Carol Dweck has done a great deal to demonstrate the significant impact of stance on our outcomes in life. Dweck’s work—captured in her 2006 book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success—focuses on one specific aspect of stance: whether you believe that intelligence is fixed. She strikes a contrast between two possible mindsets (her word for stance): a person with a fixed mindset sees personal characteristics (intelligence, creativity, humor) as being set for life, as “carved in stone”; a person with a growth mindset, in contrast, believes that basic qualities can be cultivated over time, through effort and attention.9

These mindsets translate to actions, as Dweck demonstrated with a group of fifth graders. Dweck and her team began by giving the kids a set of intriguing but doable puzzles. The kids had fun with them. But as subsequent puzzles got harder, kids with a fixed mindset enjoyed the puzzles much less and spurned the opportunity to take the hard puzzles home for practice. The kids with a growth mindset “couldn’t tear themselves away from the hard problems” and asked for ways to practice with more such puzzles.10 If your stance is that smartness is innate, Dweck found, you will behave in ways that fit with that view. Moreover, by cutting yourself off from learning, you will ensure that you do not, in fact, get smarter over time.

Modes of Learning

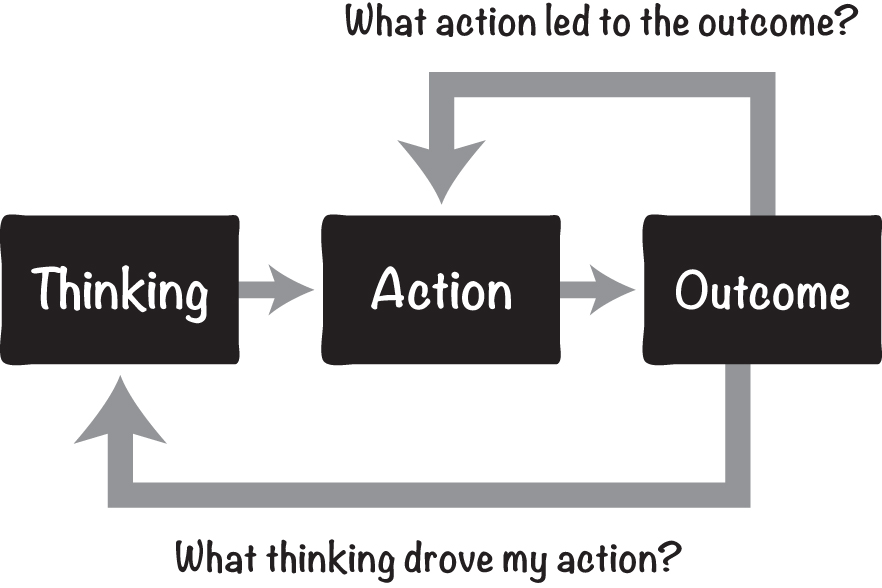

The good news is that, like intelligence, your stance isn’t fixed. It can change. But merely wishing for a more productive stance isn’t enough, because we are fighting against a natural inclination toward single-loop learning, another useful concept from Roger’s mentor Chris Argyris.11 In this default mode of being, when we get an outcome we dislike, we go back and question the actions that produced the outcome, tweaking and adjusting our actions in hopes of getting a better outcome next time (see figure 9-1).

This mode of learning seems like a good thing. After all, shouldn’t we all seek to learn from feedback? Yes, but single-loop learning is myopic. It narrowly focuses on the proximate antecedent—the action we took—while ignoring a more potent causal force: our thinking, including the reasons, rational and emotional, that we did what we did. In the face of a negative experience (or a positive one, for that matter), we rarely go back to examine our thinking, let alone to probe the stance that informed our thoughts, to see how they may have contributed to the outcome. If our reasoning is often implicit, stance is even more so, which makes it challenging to understand whether our stance makes sense, to see how it helps or hinders us, and to explore how it contributes to our outcomes.

But it does. Imagine a young man, Jason, who is looking to meet a romantic partner. Unaware of Tinder, Jason goes to a bar and tries his best pick-up line on the first attractive potential mate he encounters. If he succeeds in striking up a conversation, Jason’s view will be reinforced that hitting on people in bars is a great way to hook up. But if the person shoots him down, Jason will typically explain away the failure as one of execution: it was the wrong line, he didn’t deliver it very well, it was the wrong person, bad timing, or bad luck. It is unlikely that Jason will question his underlying thinking about the best way to find a date and his stance about relationships and romantic connections. Jason is most likely to stay in a single-loop learning mode. Single-loop learning is suboptimal in situations that produce success—but is disastrous in the face of failure. The single-loop mode tends to leave us stuck, confused, and floundering.

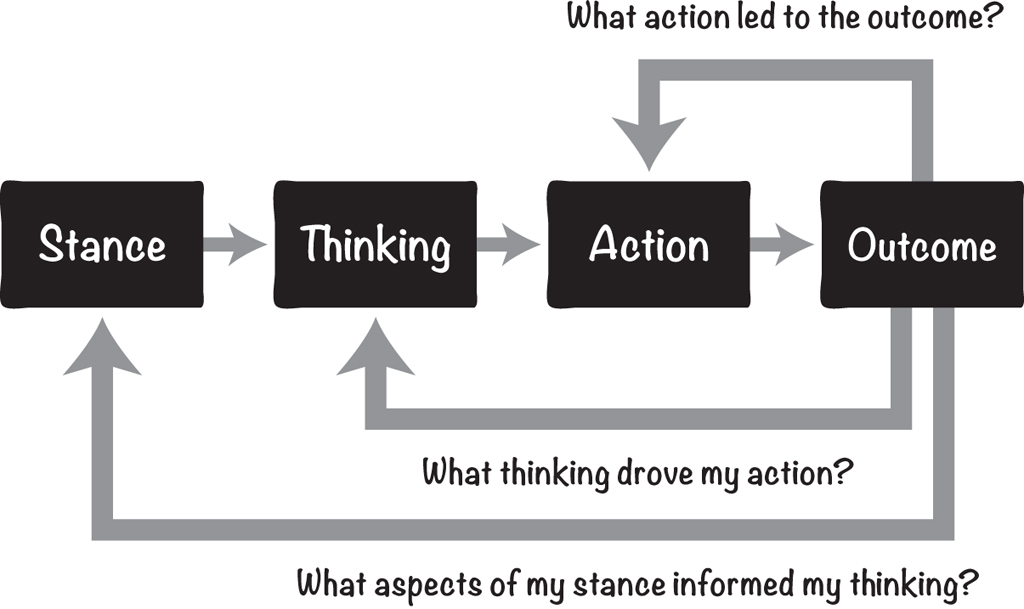

Double-loop learning, in contrast, requires that we take a step back to reflect on the reasoning that produced our action, exploring the thinking that helped produce the outcome. Argyris likened the questioning process to a journalist asking follow-up questions. Sure, the journalist can gather the facts of the story—what happened and the actions that led to those outcomes—but getting to why those actions were taken in the first place is what’s important. And once you get to the why, the real learning can take place (see figure 9-2).

The why is composed of the particular thinking and reasoning related to this situation and these specific actions, but it is underpinned by a more general stance about life. In short, it’s important to consider both the thinking and the stance when you seek to understand your outcomes, especially if you hope for different outcomes in the future (see figure 9-3).

What does all this mean in practical terms? It means we need to be willing to take the metacognitive step, not only as we work through particular business challenges but also as we more generally operate in the world. We need to think about our own thinking and explicitly link our stance to our outcomes. It means that we need to ask, What did I think that led me to take this action? And what stance would produce that thinking? To what extent is my stance helpful to me in producing the outcomes I desire? If it is unhelpful, how might I go about shifting my stance?

These aren’t easy questions. And the task of changing your stance can be daunting. How do you change something you may not fully understand? That’s why it’s important to first increase your understanding of your stance—and to do so proactively rather than right in the middle of a crisis. This is a slow and reflective process of bringing your stance to your conscious awareness, asking what you think and why you think it.

Try This

There is no right stance about the world. There is no single, most successful way to be. But for students and leaders who have gone on to be successful in their use of integrative thinking, our observation suggests that they see integrative thinking both as a process and as a way of being. They use their experiences with integrative thinking—the journey to solve wicked problems in new ways and create great choices where none previously existed—to build a productive stance about decision making. This stance has elements that are about the world and elements that are about their role in it. We share it here not as a prescription (i.e., you should hold this stance) but rather as a spur to reflection (i.e., what might happen if you experimented with holding this stance). For a summary of this stance, see figure 9-4.

A STANCE ABOUT YOUR WORLD

For integrative thinking to become a way of being, it is important to believe three things about the nature of the world.

The world is complex, so we understand it through simplified models. These models are constructions and are (at least a little bit) wrong.

Humans have a natural desire for closure. Without a feeling of being finished, we would be suspended in cognitive limbo all the time. We get physical rewards from reaching closure—a jolt of pleasure in our brains that drives those of us with a high need for cognitive closure (as psychologists call it) to struggle mightily in the face of ambiguity, desperate to get to the end. Getting to the feeling of certainty that we derive from coming to closure isn’t a purely rational process. Rather, it is deeply emotional—a “feeling of knowing” that is pleasurable, reassuring, and relatively immune to attempts to shift it.12

Integrative thinking becomes a way of being only when we reframe the idea of closure. In integrative thinking, we are never truly finished with our models. Every model we hold, no matter how much we value it, is still only a model. And that model is flawed. As Paul Polman says of the models that dominate the corporate world, “Many things the CEOs have been taught . . . [are] contrary to what you actually need in today’s world. But because we’ve been taught that, we are self-reinforcing and make . . . the situation worse.”

Rather than blindly accept orthodoxy, in integrative thinking we question the premises of that orthodoxy and push to understand the ways in which it’s imperfect. This is possible only if we accept that all models are simply constructions, and that they are incomplete. And if that is true, opposing models become helpful.

The world is understood in different ways by different people. These opposing ways of seeing the world represent an opportunity for us to improve our models.

Our own models are limited. But it can be hard to see and understand how they are limited, and to improve them, without seeking to understand opposing views of the world. As we detailed earlier, we tend to default to thinking of opposing models as wrong, and we define those who hold them as either stupid or evil. Our first instinct when we hear something at odds with our own view is to dismiss that alternative view and to distance ourselves from it. In integrative thinking, we take a different stance. Faced with a view at odds with our own, the response is, “That’s different from how I have been thinking about it. Say more.”

Haley, who studied integrative thinking in grade 12, highlights the power of this perspective: “In the past, I probably would have talked more and not listened as much, if I’m being honest. Something that is really important, I think, is realizing it’s not all about you. You can’t value your opinion over others, just because it’s yours. Realizing that everyone is equally valuable to the conversation, even the people who don’t talk as much, was the biggest thing . . . They really do have valuable things to say!”

Former General Electric CEO Jack Welch shared a similar take when he spoke with Roger in 2005: “I want someone who will argue with their teammates over a direction,” he said. “You don’t want to sit around with consensus and all agree. That’s the biggest waste of time in the world.” Shutting down opposing views may be our natural instinct, but it gives us little chance to make our models better.

Practically, openness to opposing models is about curiosity. One of our favorite examples of a corporate group expanding its own capability for curiosity comes from Canada Post, the national postal operator. Over the past five years, Canada Post has committed to training all of its leaders in integrative thinking through its LEAD 2.0 executive training program. In one of the earliest cohorts, as one group was working on a daunting action learning project, it created a new team norm: whenever individuals had opposing views—whether on the content of the project or on the process of working together—the team would go straight to quickly building pro/pro charts for the two perspectives. It became the way the team members communicated, and it helped build a team practice of diving into opposing models. It helped shift the organization’s way of being when it comes to opposing models.

The world is full of opportunity to improve our models over time, as long as we are open to the idea that a new answer is possible.

Integrative thinkers see the world as a place of possibility, understanding that the arc of human history has been one of refining and changing our models of the world over time. In science, for instance, we taught Sir Isaac Newton’s fundamental laws of physics as the right answer. It was the way we understood the physical world for hundreds of years. It was the best model we could hope for—until Albert Einstein came along and said, essentially, that it was a very good model, but it left out some important things. Einstein went on to create a new model that advanced our understanding considerably.

Integrative thinking is fostered by a belief that better answers are possible, even if they are not immediately evident. A new, superior answer is out there lurking somewhere—waiting to be discovered. This stance is tricky, in some ways, because not all attempts to solve a problem will result in an integrative solution. You won’t always find what you seek. But if you don’t go looking at all, if you settle for what we know and believe now, your chances of advancing your models are slim indeed.

This doesn’t mean that you can avoid taking action forever, because you are constantly seeking better models. Rather, it is important to balance a search for better answers with the practicalities of getting things done. Often, this means provisionally accepting an imperfect solution, knowing that the model can be improved over time in application. And it means occasionally taking the time to question models that are working just fine, to see whether there is room to improve them. This was a trademark behavior of A.G. Lafley when he was CEO of P&G; he would every so often throw a topic on the table for discussion, just to see whether there might be a better way to think about it.

A STANCE ABOUT YOUR ROLE IN THE WORLD

A person’s stance also includes an understanding of self and identity. When it comes to the integrative thinker’s stance about his role in the world, there are also three elements here.

My job is to get clearer about my own thinking, opening it to inquiry so that I can better understand my own model of the world.

Integrative thinking doesn’t mean entirely giving up on your existing models or losing all confidence in your own thinking about the world. It is a more nuanced stance that says, “I feel pretty good about my model. I like it a lot. But I know it is limited. So I will question it and open it up to others in hopes that they can help me understand those limitations more clearly.”

This balanced view requires confidence in yourself and your ability to think through models with others without being triggered by the need to be correct or to show that you are the smartest one in the room. When we first began teaching integrative thinking to children, we worried that the kids would be paralyzed by the notion that there are no right answers. What surprised us was that knowing their models are wrong was freeing for kids—because it means that everyone else’s models are wrong, too. Lauren, age twelve, explains: “In the past, I would not raise my hand when a teacher asked a question, because I was afraid of getting it wrong. [But] I’m more confident [now] because we were taught that nothing is necessarily a really bad idea. You can always put some good into it. Because in good there’s always some bad, but in bad there’s always some good. But you have to dig deep down to find the good sometimes.”

This aspect of a person’s stance requires an appreciation of the value of thinking about thinking—not for its own sake, not in an endless loop of navel gazing, but for the purpose of finding integrative solutions.

My job is to genuinely inquire into opposing views of the world to understand and leverage those opposing models.

The process of engaging with opposing models is challenging, in part, because those who hold opposing models often are not our favorite people. We tend to like people who agree with us. Unfortunately, people who agree with us are far less helpful in advancing our thinking than are those who disagree. Those with opposing views are the ones best positioned to help us question our models and advance them.

To productively engage with opposing views, we need not abandon our own. Instead, we need to strike a balance best summed up, again, by Chris Argyris, who introduced us to a mantra that can help: “I have a view worth hearing, but I might be missing something.” My view is worthwhile, in other words, but it is probably incomplete.

Considering opposing models adds to the complexity of your life. It is simpler by far to consider only one model—your own. Engaging with other models means diving into complexity, not to wallow in it or get consumed by it but to use other models, via the integrative thinking process, to get past the complexity to a simple, elegant new model. Integrative thinkers do not shy away from complexity, because they understand that it’s their job to engage with complexity in order to create a great choice.

My job is to patiently search for answers that resolve the tension between opposing ideas and create new value for the world.

Successful integrative thinkers have faith that they, together with their teams, can generate great choices. Maybe not right away, and maybe not every time, but eventually they can do it. And it is clear that the task falls to them and not to someone else. It is the integrative thinker’s job to solve the problems she sees in the world. Here is how Polman puts it:

How do you deal with these trade-offs, all these tension fields? I actually have moved myself to a different mindset: How do you move these tension fields? Most people act as they do because of boundaries that are placed upon them. But they react to the symptoms, not to the boundaries. So most CEOs would react to the symptoms: “Are the shareholders short term? I have to run my business on the short term.” They don’t say, “How can I change the boundaries? Why do the shareholders react short term?” If you change boundaries, you actually change behaviors. It’s much more motivating to spend my energy on trying to move these boundaries.

It is this motivation, and faith in one’s abilities to shift boundaries, that makes integrative thinking possible.

Integrative thinking is a task that also requires patience. As Victoria Hale, one of the integrative thinkers we interviewed early on, eloquently put it, “I stay with it, sit with it, spin it around.”13 She knew that coming to an integrative solution was worth the work, and she didn’t attempt to rush her thinking. Rushing, she knew, would make it less likely that she would actually solve the problem she’d set out to solve. This doesn’t mean she was willing to think forever—but she was willing to patiently use the time she had to think hard and seek insights toward a great new choice.

These six elements of stance can shift the way you are in the world, and they can have a dramatic impact on your outcomes over time. If you see little similarity between this stance and your own, don’t fret. It turns out that you do not need to have this stance in order to practice integrative thinking. In fact, practicing integrative thinking may be the most effective way to cultivate this stance over time. Even a small shift in what you do each day can be a catalyst for a substantial change in mindset, like the one we saw in Jabril.

JABRIL’S STORY

Jabril was a student in a grade-12 integrative thinking class taught by our colleague Nogah Kornberg and a teacher named Rahim Essabhai. Jabril was an outstanding basketball player, but perhaps not always the most attentive student. After the course was finished, we asked him what he felt had changed about himself. Here is what he had to say.

Before, I was one of those guys who, when I came up with one idea, one conclusion, I’d just stick with it. Like, I was just too stubborn to change it. “That’s the answer, I’m sticking with it.” Like how you do multiple choice: the first question you circle, you think, “Is it wrong? Should I circle something else?” I’d just stick with it. [That’s] just how I was before I joined the class. I used to write everything with pen before, but I started writing in pencil right after I finished the class. It just became like a habit . . . When I do my short answers, I write with pencil. I just write something that first comes to mind, and then I read it over again, and it just continues flowing: I expand, and I erase, and my answers just keep getting better and better throughout.

Jabril used to write in pen. And now he writes in pencil. On one level, using a pencil is a tiny shift. On another, it signals a profound change. Because now every answer can be improved, and it can just keep getting better and better.

This is the stance that helps us create great choices. It spurs us to metacognition, empathy, and creativity. It helps mitigate some of our most sticky cognitive biases. And it provides a powerful platform for a different way of thinking about the world—one that leverages the tension of opposing ideas to create new choices and new value.

That said, integrative thinking is not a silver bullet. It is not the single thinking tool for all circumstances. But when you find that your conventional thinking tools are not helping you to truly solve a problem, integrative thinking can be the tool that shifts the conversation, defuses interpersonal conflicts, and helps you move forward. So in those situations when the choices in front of you are not good enough, work through the integrative thinking process: articulate the tension, examine the two models, generate possibilities to resolve the tension, and then test those prototypes.

The process may not provide brilliant answers every time, but it will always help make your thinking clearer, boost your curiosity about other people’s models, and give you room to create. And that, after all, is the goal: not to choose between mediocre options, but to create great choices.