Chapter 3

Infiltrating the Crowd

In This Chapter

![]() Tracing the crowdworker’s process

Tracing the crowdworker’s process

![]() Applying insider knowledge to your crowdsourcing

Applying insider knowledge to your crowdsourcing

![]() Becoming a Wikipedia contributor

Becoming a Wikipedia contributor

![]() Getting to grips with the biggest platform: Mechanical Turk

Getting to grips with the biggest platform: Mechanical Turk

![]() Exploring the Zooniverse

Exploring the Zooniverse

Most of this book clues you in on crowdsourcing from the point of view of the crowdsourcer, the person who designs and manages the crowdsourcing activity. But just as bosses in organisations benefit from getting out on the shop floor, being part of the crowd yourself enables you to gain a good understanding of crowdsourcing.

From within the crowd, you see how the crowd works and how it deals with specific crowdsourced jobs. You notice how individuals interact with the crowdmarket, which tasks are difficult and which are easy, which instructions guide you to do the job well and which are confusing. And you develop a keen sense of which skills are actually needed for a task.

The most experienced crowdsourcers spend a few minutes each day in the crowd. Doing so lets them see whether their crowdsourced job is going well and lets them keep an eye on what their competitors are doing.

In this chapter, I help you take a walk in the crowdworker’s shoes, which can help you gain valuable knowledge to inform your crowdsourcing activities. First, I walk you through the crowdworker’s process, and then I pick out key lessons you can take from being in the crowdworker’s shoes. Finally, I suggest three major crowdsourcing activities for you to try out: Wikipedia, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and Zooniverse.

Following the Crowdworker’s Steps

To undertake crowdwork, you usually take these five steps:

1. Register at the crowdmarket.

The crowdmarket is the place where crowdsourcers and crowdworkers meet. Crowdsourcers bring tasks that they need to have done. Crowdworkers come to do those tasks (for more details, head over to Chapter 2). Sometimes, crowdmarkets don’t look much like a market. Wikipedia, for example, doesn’t look much like a market, but it is one. Other crowdmarkets, though, such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk or Elance or oDesk, look exactly like markets.

Because crowdmarkets don’t always look like marketplaces, people often refer to them as crowdsourcing sites or crowdsourcing platforms. Registering at a market is just like registering at any commercial website: you create an identifier and password for yourself and give the site a certain amount of personal information.

Because crowdmarkets don’t always look like marketplaces, people often refer to them as crowdsourcing sites or crowdsourcing platforms. Registering at a market is just like registering at any commercial website: you create an identifier and password for yourself and give the site a certain amount of personal information.

If the market pays its workers, the workers also have to give their tax information. In the USA, a worker has to give his social security number; in the UK, it’s the National Insurance number; and in Australia, it’s the tax file number. The worker may also have to give details of a bank account or PayPal account so that the market can transfer his earnings.

2. Verify your skills.

Crowdmarkets usually ask workers to demonstrate their skills. They verify your skills in different ways, depending on the kind of crowdsourcing that you’re doing. (For more on different types of crowdsourcing, check out Chapter 2.)

• Crowdcontest markets sometimes ask for your credentials, but they often ask only for your submission. Crowdcontests are more concerned with your submission than with the background of the workers.

• Macrotask markets usually ask for information about the background of workers, requesting academic credentials and examples of prior work.

• Microtask markets ask potential workers to do sample tasks to show that they can complete the work correctly. Often, these sample tasks are associated with specific collections of tasks. If you move from one group of tasks to another – from transcribing business cards to reviewing web pages, for example – you complete a new sample task to demonstrate your skills.

• Self-organised crowds generally avoid tests to check the skills of the individual workers. Instead, they rely on reputations. Self-organised crowds recruit members who are connected to existing members of the crowd, who have a portfolio of work, and who post their accomplishments on the crowdmarket. The crowd quickly finds out if a new worker has exaggerated his reputation or can’t do the work.

• Crowdfunding generally asks only for your credit card. If your money is good then the crowdsourcer is happy with you.

3. Choose a task.

If the market deals with crowdcontests, microtasks or macrotasks, it displays the tasks in lists or lets you search a database of tasks for specific kinds of jobs. In these types of tasks, you can generally read the full description of the job before you accept it.

Most markets let you return a job after you’ve started it. If you conclude that you’ve made a mistake, you can click a Return button and send the task back to the market. Returning a job you don’t want to do is always better than completing it badly. If you make errors in a task, those errors reflect on your reputation score.

Crowdfunding sites give you a list of projects that are seeking funds. They work much like microtasking or macrotasking sites.

Sites promoting self-organised crowds provide lists of groups that you may want to join.

4. Do the work.

As a crowdworker, you often complete the task at your computer. Some of the tasks take a lot of time, others very little. The better markets give you an estimate of the effort that you need to expend on a task.

Some tasks require you to do research on the web. Others ask that you use resources of your own. Many ask you to use a piece of software that they developed. Often this software is connected seamlessly into the market. When you use Zooniverse, for example, you use this kind of software to count craters on the moon or look for planets of distant stars.

5. Submit your work.

After you complete the task, you send your work to the market. When your work is at the market, it’s reviewed by the crowdsourcer to make sure you’ve done it properly. He checks to make sure that you’ve followed the instructions and that every part of the task is complete. In some circumstances, such as for microtasks, this review happens very quickly. At other times, notably in crowdcontests and macrotasks, the review takes several hours or even a couple of days.

While the completed task is under review, you can select another task and start work on it.

Taking Lessons from Your Time as a Crowdworker

As you live the life of a crowdworker, you begin to gain an understanding of the nature of these workers. You discover that crowdworkers aren’t invisible individuals, that they need training, that they need clear instructions. If you work long enough, you also discover that crowdworkers have the power of movement. If they don’t like a job, they can leave it and move on to another.

Lesson 1: Crowdworkers have names and reputations

When you work in crowdsourcing, you’re quickly reminded that it’s a human activity and that crowdworkers are real people with goals and reputations that shape the way they work. You can easily forget these facts when you’re planning or managing a large crowdsourcing job. It’s also easy to forget the value of a good reputation to a crowdworker.

The first thing you learn from working in a crowdmarket is that crowdworkers have names and reputations. Often, names are masked by identifiers applied by the market, but the reputations are not. Good reputations enable workers to get the best jobs or to demand the highest pay. Mediocre reputations force workers to take uninteresting work or low-paying tasks.

Crowdworkers often try to protect or improve their reputations. They try to gain qualifications for new skills or get crowdsourcers to give them a top review on a task. If a reputation is summarised in a numerical scale, as it is at many crowdmarkets or crowdsourcing sites, workers may protest a low score or a claim that they didn’t complete a job correctly.

At most crowdmarkets or crowdsourcing sites, crowdworkers can’t easily abandon their reputations and build a new one from scratch. When crowdworkers register at crowdmarkets, they’re required to give their real names and their real tax identifications. Only if you’re working for free can you can hide behind an invented handle.

Lesson 2: Crowds need training

When you spend some time as a crowdworker, you quickly learn that training’s important. Workers can’t just log on to a crowdmarket and become an expert crowdworker, just as you can’t expect to be a great writer simply by turning on a word processor, or a great game player by merely logging in to a game. You always need to find out what to do.

Even the simplest tasks require training. When you prepare a task for the crowdmarket, think about how you’ll prepare the workers for that task. You need to teach them how to get the information that they require, how to go through the steps of the task, how to check to see that the work’s properly done, and how to return the work to the market.

When training crowdworkers, you may have to spend a little time helping them to deal with ambiguity. Sometimes, the workers will start a task and conclude that the work they have to do doesn’t quite match the instructions they’re supposed to follow.

For example, suppose the crowdworkers are transcribing a short audio file, which is a common task on crowdmarkets. The instructions tell them to listen to the file, type the words that they hear into a field on the site, and then push a button marked Submit.

Those instructions sound complete enough, but think about what the workers should do if they don’t understand all the words, if they hear two people talking at the same time, if the words are in a language that they don’t understand, or if they hear something that the crowdsourcer never anticipated.

In this example, you’ll want to train your workers to take a specific action when they can’t complete the task. You might ask them to write ‘cannot transcribe words’ if they can’t transcribe even a part of the tape.

If you don’t tell your workers what to do, each worker will make a different judgement when they can’t understand the words. Some will make a valiant effort and guess the words. Some will do only part of the task. Some will return the task untouched. As a result, you, as the crowdsourcer, will have to review the work for each task and determine what each worker meant.

Lesson 3: Crowds want clear instructions

Nothing frustrates crowdworkers more than an instruction they don’t understand. And if they don’t understand what you want, they won’t take your job.

Good, clear instructions tell crowdworkers the:

![]() Actions to take

Actions to take

![]() Data to find

Data to find

![]() Judgements to make

Judgements to make

![]() Format for the work

Format for the work

The guidelines for writing clear crowd instructions are no different from the guidelines for writing any form of instructions:

![]() Keep sentences short.

Keep sentences short.

![]() Use a direct voice.

Use a direct voice.

![]() Use plain English.

Use plain English.

![]() Whenever possible, test the instructions on a friend.

Whenever possible, test the instructions on a friend.

Lesson 4: Crowds are free to move

‘Plenty more fish in the sea’ is the advice you may give a young person whose relationship has failed. For crowdworkers, the sea is filling up with more and more fish every day.

Crowdworkers aren’t bound to a single job. They’re free to move about. If they don’t like a task or become bored with it or get angry because their payments are delayed, they can go in search of other work. Just because you have a crowd today doesn’t mean that you’ll have a crowd tomorrow.

Yet crowdworkers do develop loyalties. They find certain kinds of work satisfying. They enjoy building skills on specific kinds of tasks. They like to identify with a specific institution, even if they occasionally disagree with the goals or ideals of that institution.

As a crowdsourcer, you want to keep the crowd interested in your work and your tasks. You develop a reputation just like a crowdworker, although most markets don’t yet keep a reputation score for those who provide jobs.

One of the ways to encourage workers to stay at your crowdmarket or crowdsite is to offer recognition for workers who have completed a certain number of tasks. You might call these recognitions bronze, silver and gold stars. When they’ve completed 50 tasks, for example, you give them a bronze star, you give a silver star for 100, and a gold star for 200. You can keep a leaderboard to show the names of everyone who’s received stars and, perhaps, each week you might also a small financial reward to the workers who’ve completed the most tasks that week. These techniques are often part of a process known as gamification.

Joining the Staff of Wikipedia

If you want a simple starting point to find out about crowdwork, head to Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org). Wikipedia is one of the most visible and accessible crowdsourced activities, and it illustrates the basic structure of crowdsourced work (see the earlier section, Following the Crowdworker’s Steps). You register as a worker, choose a task, complete the task, and submit the task for evaluation. The only step you don't do is demonstrate your ability to do the work before you take a task. Wikipedia judges all work by the quality of the submission, not by the qualifications of the contributor.

Registering as a worker

To register as a contributor to Wikipedia, simply go to http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page, click the 'Create account' link in the top-right corner of the screen, and type in a username, password and (optional) your email address.

That’s it! Because Wikipedia doesn’t pay its contributors, it doesn’t require you to give any information for tax identification. You also don’t have to give your real name. However, your user name is identified with your contributions. If you’re a reliable contributor, the editors recognise your ability. If you’re unreliable or regularly violate the Wikipedia guidelines, you acquire a poor reputation. Eventually, one of the senior volunteers will notice your reputation, especially if you make a lot of changes to a small group of entries. If that volunteer decides that you’re causing more trouble than you’re worth, he can ban you from participating in Wikipedia again.

Choosing a task

Most commonly, you will be editing an existing entry. Wikipedia is now a large and comprehensive encyclopaedia that already has articles on most common subjects and many uncommon ones. Still, you may find a topic that lacks an entry and be the first to create one.

Completing a task

In the article you want to modify, click the ‘Edit’ tab at the top of the page, which gives you access to the editor.

You can use the editor as you would any word processor to select words, delete text and write new sentences. However, you have to follow the guidelines for Wikipedia contributions as well as the mechanics of editing.

As one of its five pillars or principles, Wikipedia claims that it has no firm rules. However, it does have general guidelines for contributors, which you can find at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Wikipedia_in_brief. These guidelines ask you to:

![]() Write from a neutral point of view.

Write from a neutral point of view.

![]() Target an encyclopaedia audience.

Target an encyclopaedia audience.

![]() Avoid original research.

Avoid original research.

![]() Avoid plagiarised or copyrighted materials.

Avoid plagiarised or copyrighted materials.

![]() Keep to the facts.

Keep to the facts.

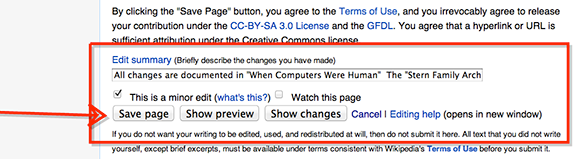

Submitting a task

As with many crowdsourcing markets, Wikipedia asks you to submit your complete work in a formal manner. After you complete your writing, you review your work for errors and then you scroll down to the bottom of the page to the ‘Edit Summary’. There, you fill in details of the nature of the changes you’ve made to an article and then click the Save Page button to send the material to an editor (see Figure 3-1). Wikipedia publishes the changes immediately, but editors can remove them if they believe that the modifications aren’t appropriate.

In the formal submission, Wikipedia also notifies you of all the legal requirements for contributors. As a contributor, you have certain rights and obligations that you acknowledge when you submit your work.

Reproduced with permission.

Figure 3-1: Wikipedia submission.

Leaping into the Market with Amazon’s Mechanical Turk

At the time of writing, Amazon's Mechanical Turk (www.mturk.com) is the largest and most heavily used crowdsourcing platform. The site is really a nothing more than a simple job market. On Mechanical Turk, you can find large jobs that offer large payments or small, quick tasks that pay pennies. Individuals, academic researchers and large crowdsourcing firms use the platform.

Mechanical Turk workers (they sometimes go by the name ‘Turkers’) go through the five steps for crowdworkers outlined in the first section in this chapter.

To learn how Mechanical Turk operates, go ahead and do a couple of the tasks that are common to the site. For example, a common task is to find the number of people who ‘like’ a certain product or artist on their Facebook page.

Registering as a worker

Go to www.mturk.com and click the link in the upper right-hand corner. Doing this enables you to log on to the crowdmarket as a worker. (Amazon's Mechanical Turk uses its own terms to describe crowdsourcing. They often call crowdsourcers by the name of requesters.)

Registration is much like that for any commercial site. You have to give your correct name and, when you reach the last page, you have to give your tax information. In the USA, you have to enter your social security number. If you live outside the USA, you can get a US social security number by filing a foreign worker form with the Internal Revenue Service. The Mechanical Turk software helps you do this. If you don’t have a US social security number, you have to take your earnings in the form of Amazon products.

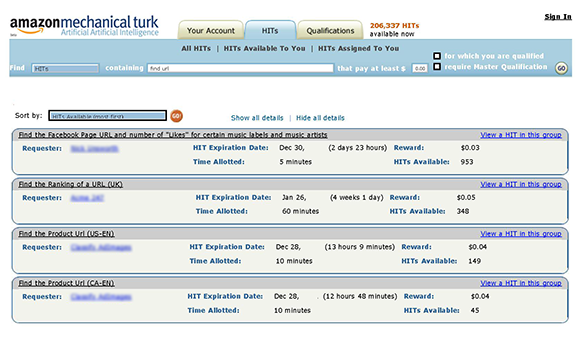

Selecting the task

Mechanical Turk calls the basic task the Human Intelligence Task, or HIT. It lists these tasks on a screen such as the one shown in Figure 3-2. Each of the rounded rectangles describes one set of similar tasks or HITS. The group with the largest number of available tasks is listed first.

The title of each task is given in the upper left-hand corner of the record. For example, the title of the top set of tasks is ‘Find the Facebook page URL and number of “Likes” for certain music labels and music artists’.

From the record, you can also see the payment or reward offered for each task and the number of tasks of this type that are available. In this case, the requestor’s offering $0.03 and has 953 individual tasks or HITs in its pool.

You find the two key pieces of information about the tasks in the middle of the record. The HIT Expiration Date tells you that these tasks can be found on Mechanical Turk until 30 December or until they’re done, whichever is first. Time Allotted tells you that Mechanical Turk will give you five minutes to complete the HIT after you start it. If you haven’t completed it in five minutes, the program withdraws the task.

Reproduced with permission from Amazon.com.

Figure 3-2: Tasks (HITS) on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk.

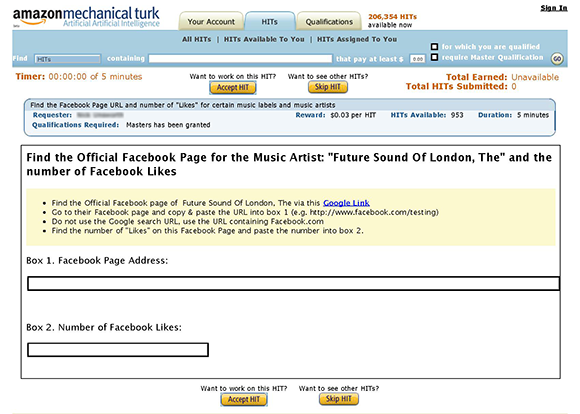

To see an actual task in this first group of HITS, click on the text that reads ‘View a HIT in this Group’ in the upper right-hand corner of the rectangle. Next, the screen shown in Figure 3-3 will appear. This screen describes the task in detail and shows the work that you’d have to do to complete it. This task is pretty easy. It asks you to find the Facebook page of a band called The Future Sound of London, and gives you instructions to find the number of people who like this band. It also has two fields. In the first, you put the address (or URL) of the band’s Facebook page; in the second, you put the number of people who ‘Like’ the band.

If you like the task, you can click the Accept HIT button at the bottom and go ahead and do the work. If you decide that it doesn’t interest you, you can click on the Skip HIT button and go on to another task.

Qualifying and completing the task

Now that you’ve accepted the task, you need to become qualified. Each requestor has its own way of qualifying crowd workers. Usually, the crowdsourcer asks you to do a special task. These tasks look like any other tasks but have an answer that the requestor knows. If you get the right answer, you can do more tasks; if you don’t, you have to correct your answer before you can proceed to the next step.

Reproduced with permission from Amazon.com.

Figure 3-3: A task to find who likes a band on Facebook.

After you’ve completed the example task, click the Submit HIT button. If you don’t like what you’ve done, click Return HIT and your answers won’t be recorded.

Some requestors require you to do only a single example task before you can start to work. Others require several test tasks. In all cases, the requestor can check your responses to these examples and reject you if you aren’t doing the work properly.

After you qualify to work on this specific pool of tasks, you can return to the starting screen (Figure 3-2) and request a new task. You complete this task and click the Submit HIT button, which sends the task for the requestor to review.

Donning the White Lab Coat: Zooniverse

Crowdsourcing isn’t always done for profit as it is with Mechanical Turk. For generations, scientists have used crowds to gather process data. After all, scientific research is a form of production. (One well-known scientist joked that research merely took the raw materials found in caffeinated beverages and turned them into important scientific results.)

One of the more prominent scientific crowdsourcing markets is Zooniverse (www.zooniverse.org). Scientists place projects on Zooniverse and ask the crowd to analyse photographs, gather data, look for patterns in data, and transcribe old documents. Zooniverse doesn't pay its crowd in money. Instead, the workers at Zooniverse gain satisfaction from doing this work, because they feel they're contributing to a cause that's bigger than themselves.

The Zooniverse marketplace is simple, because Zooniverse is a volunteer site. Potential workers have to register with the site, but they don’t have to provide much information. You have to create a logon name, which can be your real name or a name that you’ve invented. You also have to create a password, so that someone doesn’t try to use your identity, and give an email address so that Zooniverse can keep in touch with you. Zooniverse also asks for your full name, because sometimes scientists want to thank everyone who worked on the research. However, you don’t have to give your name if you don’t want to.

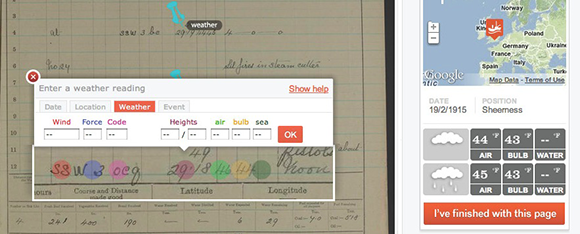

The homepage of Zooniverse gives a list of projects currently on offer. One of the projects you can get involved in is called Old Weather (see Figure 3-4).

As a rule, meteorologists are people who stick close to their desks and never go to sea. They get a better understanding of weather by processing data then by standing in the rain. Meteorologists have found great value in the log books of the British Royal Navy, which contain one of the most complete records of global weather data. Once the sun never set on the British empire, and it certainly never set on the British naval officer who had to record weather data six times a day.

The logs of the British Navy are handwritten, and no computer can scan them successfully. Examples include: ‘Pistols explode,’ ‘Seamen abscond with dinghy,’ and ‘Prayer services held.’ Even the best programs may not realise that these events had anything to do with the weather.

For each task, the crowd is shown a single page of a ship’s log. When they see something of interest on the page, they’re supposed to move the cursor to that point and click. The Zooniverse interface then opens a little window, which allows the worker to transcribe the information. The boxes for weather data have specific fields for wind, temperature and barometric data (see Figure 3-4).

Reproduced with permission from Zooniverse.

Figure 3-4: Old Weather project screen on Zooniverse.

Albert Einstein said, ‘Everything should be kept as simple as possible, but no simpler.’ This principle certainly applies to training crowdworkers.

Albert Einstein said, ‘Everything should be kept as simple as possible, but no simpler.’ This principle certainly applies to training crowdworkers.