CHAPTER 8

Developing Cultural Intelligence in an Interconnected World

THE BULL IN THE CHINA SHOP

Barbara Bull, the American public relations officer of a Beijing hotel, was annoyed with Weixing Li, a Chinese staff member who had repeatedly turned up late.

“Do you know what you did wrong?”

His response was a blank stare.

“Do you know what you did wrong? Do you know why I am upset?”

Another blank look.

“Do you know what you did wrong?”

“Whatever you say I did wrong, I did wrong,” he replied.

Barbara was taken aback. What did he mean? “I want you to tell me what you did wrong!” she said.

“Whatever you say I did wrong, I did wrong. You are the boss. Whatever you say is correct. So whatever you say I did wrong, I admit to.”

This made her even angrier. So she told him exactly what he had done wrong, describing his irresponsibility, immaturity, and failure. He apologized and said no more. He looked downcast. Did he understand the problem? Would he change?

Later, Barbara had a conversation with her fellow manager Chrissie, who has been in China for several years. When Barbara described what had happened, Chrissie nodded. What Barbara had experienced, she explained, was a common problem. Barbara simply did not understand the importance of mianzi to Chinese people.

“Mianzi is what Westerners would call ‘face,’ as in ‘saving face’ or ‘losing face.’ In Chinese culture it is the motivating force behind many actions. Chinese employees tend to see things from a hierarchical viewpoint. Weixing probably knew he had done something wrong, but he would have handled it by letting his boss point out what he should have done. Instead, you made him lose face, which was bad for his commitment to the company, though fortunately you didn’t reprimand him in front of others. But he would see the loss of face as applying not just to himself but to you. Instead, you might have explained how his actions had caused both you and the company to lose face. That would have caused him shame, and he might have learned.”

“Wow! I’ll try to remember that next time I want to blow my top. But being in a foreign country is like walking on eggshells. People’s egos are so easily crushed. How am I supposed to know these things? How can I practice?”

This case presents a paradox of cultural intelligence. The paradox is this:

In order to acquire cultural intelligence you must practice, by living and working in culturally different environments, or by working with culturally different people.

But

In order to live and work effectively in culturally different environments, or to work successfully with culturally different people, you first need to acquire cultural intelligence.

This is a difficult problem. It means that Barbara and Weixing and others like them must do two things at once: continuously observe and learn cultural intelligence at the same time as they practice it. Barbara was too intent on getting Weixing to diagnose his own error, and Weixing held on to his Chinese beliefs about hierarchical relationships. Perhaps both will learn enough from their encounter for it to transfer to the next intercultural situation. And by sharing the problem with an experienced colleague, Barbara has been able to add to the knowledge component of her cultural intelligence. This aspect of the case reminds us that cultural intelligence is not developed through mere exposure to other cultures but requires conscious effort.

Characteristics Supportive of Cultural Intelligence

Some characteristics that individuals already possess or can develop make them more willing and better able to increase their cultural intelligence. For example, personality traits such as openness to new experience, extroversion, and agreeableness, improve the capacity to acquire the necessary skills. Again, mindfulness is key because, combined with the active pursuit of opportunities for cross-cultural interaction, it lays a foundation for developing greater cultural intelligence.

Developmental Stages of CQ

The development of cultural intelligence occurs in several stages.

Stage 1: Reactivity to external stimuli. The starting point is a mindless adherence to one’s own cultural norms, typical of people with little exposure to, or interest in, other cultures. These people may not even recognize that cultural differences exist, or may consider them inconsequential. They may say things like “I don’t see differences. I treat everyone the same.”

Stage 2: Recognition of other cultural norms and motivation to learn more about them. Experience and mindfulness produce a new awareness of the multicultural mosaic around us. The individual is curious and wants to learn more but may struggle with the complexity of the cultural environment and search for simple rules to guide behavior.

Stage 3: Accommodation of other cultural norms in one’s own mind. Reliance on absolutes disappears. A deeper understanding of cultural variation begins to develop. Different cultural norms and rules become comprehensible and even reasonable in their context. The individual knows what to say and do in different cultural situations but finds it difficult to adapt and often feels awkward.

Stage 4: Assimilation of diverse cultural norms into alternative behaviors. At this stage, adjusting to different situations no longer requires much effort. Individuals develop a repertoire of behaviors from which they can choose depending on the situation. They function in different cultures effortlessly, almost as if they were in their home cultures. Members of other cultures accept them and feel comfortable interacting with them. They feel at home almost anywhere.

Stage 5: Proactivity in cultural behavior based on recognition of changes in cues that others do not notice and changes in cultural context, sometimes even before members of the other culture recognize them. Individuals at this stage are so attuned to the nuances of intercultural interactions that they automatically adjust their behavior in anticipation and know how to execute it effectively. Such individuals may be rare, but they demonstrate a level of cultural intelligence to which we might all aspire.

Culturally intelligent people have a cognitively complex perception of their environment. They can make connections between seemingly disparate pieces of information. They describe people and events in terms of many different characteristics and can see the many links among these characteristics and the coherent pattern in a cultural situation. They see past the stereotypes that a superficial understanding of cultural dimensions—such as collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, and power distance (Chapter 2)—provides. Knowledge of these dimensions is only a first step in developing cultural intelligence.1 Culturally intelligent people see the connections between a culture and its context, history, and values.

The Process of Developing Cultural Intelligence

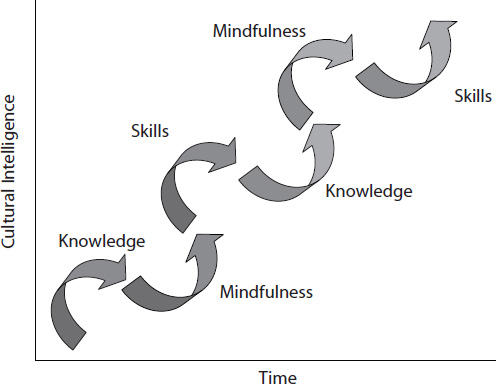

Raising your CQ requires experience-based learning that can take considerable time. You need a base level of knowledge, the acquisition of new knowledge and alternative perspectives through mindfulness, and the development of this knowledge into behavioral skills. The process is iterative and can be thought of as a series of S curves, as shown in Figure 8.1.2

The acquisition of cultural intelligence involves learning from social interactions. Such social learning is a very powerful way of transferring experiences into knowledge and skills.3 Social learning involves attention to the situation, retention of the knowledge gained from the situation, reproduction of the behavioral skills observed, and finally reinforcement (receiving feedback) about the effectiveness of the adapted behavior.

Improving CQ by learning from social experience means paying attention to, and appreciating, critical cultural differences between oneself and others. This requires knowledge about how cultures differ and how culture affects behavior, awareness of contextual cues, and openness to the legitimacy and importance of different behavior. To retain this knowledge, we must transfer our learning from the specific experience to later interactions in other settings. To reproduce the skills, we need to practice them in future interactions. To reinforce the skills, we need to try out behaviors frequently and mindfully.

As implied by Figure 8.1, improving your CQ takes time, and you must be motivated to do it. The iterative and long-term nature of gaining cultural intelligence is illustrated in the following example.

FIGURE 8.1. The development of cultural intelligence

UNDERSTANDING THE FRENCH

Jenny Stephens, a U.S. national, is an executive for the French subsidiary of an American multinational. After meeting and marrying a Frenchman in New York, she moved to Paris, where she has lived for seven years. She speaks French fluently and regularly interacts with French relatives and friends and colleagues. When asked if she feels she understands French culture, she says

I have been here for seven years. I have found that whenever I would begin to get a sense that I really understand the French, something strange would happen that would throw me off completely. As I would reflect on the event and discuss it with my husband and friends, I would develop a more complex view of the French. Then, things would go fine for several months until the whole process would repeat itself.

For example, I felt I was making progress when I learned how to buy cheese. Putting together a proper cheese plate in France is as complicated as choosing wine correctly. A perfect cheese presentation must contain five cheeses—a ripe (but not too ripe) light, soft cheese; a hard, sharp cheese; a goat cheese; a semisoft cheese; and a blue cheese. However, just knowing this is insufficient to be viewed as anything but a novice in a French cheese shop. To be truly expert, one must know what cheeses from what regions are particularly good at the moment. When I learned that by simply using my basic knowledge and asking appropriate questions such as what brie is particularly good this week, I was treated with much more respect.4

In this case Jenny is practicing mindfulness by recognizing unusual things that she observes as being related to culture and talking them over with others. She also uses mindfulness when she recognizes that her limited knowledge can be used effectively by planning how to adapt her behavior. In this way, each instance of idiosyncratic French behavior builds on her previous knowledge and contributes to her development of cultural intelligence.

Activities That Support the Development of Cultural Intelligence

Perhaps the most important means of increasing cultural intelligence is spending time in foreign countries, in which cross-cultural experiences will be frequent and CQ will increase through necessity. While foreign experiences are ideal, there are numerous other situations and activities you can draw upon, ranging from formal education to informal interactions, including developing relationships with others who are culturally different.

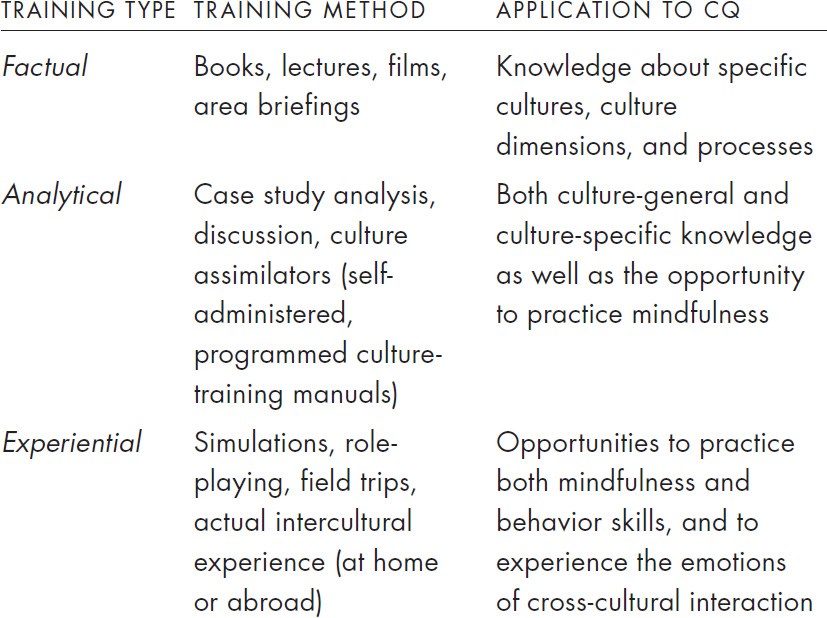

FORMAL EDUCATION/TRAINING

The types of formal training available on cultural intelligence can be classified in terms of being experience-based (as opposed to purely “classroom”) and being culture-specific or applicable across cultures. All these types are valuable, but cultural intelligence requires learning from experience and building skills that can be applied across cultures. The following chart shows the types of formal training available and how they apply to our model of developing a high CQ.

Of the three types of methods, formal experiential training is the most rigorous and effective but is rare and often expensive. Most of us therefore rely on our day-to-day interactions with culturally different others, in different contexts: multicultural teams, interactions with culturally different individuals at home, and foreign assignments.

MULTICULTURAL GROUPS AND TEAMS

Because of globalization, our work groups are increasingly multicultural, offering rich opportunities to gain cultural intelligence by observing the behavior of individuals from different cultures responding to the same situations. Examples include the assignment of group roles, the establishment of a leader, and the imposition of deadlines. If we are mindful, we will note the wide variety of reactions from culturally different members to the group’s behavior. The interactions of culturally different people in groups are complex, but this complexity generates great learning opportunities to develop greater cultural intelligence.

CROSS-CULTURAL INTERACTIONS AT HOME

The numerous learning opportunities that multicultural societies present us with often lack the depth and intensity that is required for us to learn from them. For a Westerner, having dinner at a Cantonese restaurant and interacting with the Chinese service people is indeed an intercultural experience, but it is a very mild one (although it might become a bit more intense with an order of chicken feet!) and lacks significant engagement. Just as leadership skills are often taught by testing the leaders of groups engaged in challenging outdoor activities such as ropes courses, significant CQ development requires us to move outside our comfort zone and to challenge ourselves in deeper ways.

In our international management courses we, the authors, routinely require our students to practice the skills they have learned in class by engaging in a non-trivial cross-cultural experience in their local area. “Culture” in this case is not confined to national or ethnic culture but, consistent with our definition in Chapter 2, can be applied to any social group. Subcultures within a culture provide excellent learning experiences. We tell students that if they are to learn, they should feel culturally uncomfortable in the situation, at least at first. Some ways to engage in cross-cultural experiences are to

• Locate an ethnic organization in your community and attend (and participate in, if possible) a cultural celebration. Ask members to explain the significance of the event and the symbolism of the activities.

• Find an interest group that represents a set of beliefs to which you do not subscribe and attend one of its meetings. For example, some of our heterosexual university students have attended meetings of gay and lesbian associations.

• Attend a religious service or wedding ceremony of someone from another culture. Ask a member of the culture to explain the significance of the rituals involved. One of our mature MBA students, a Japanese-Canadian, visited the home and attended the temple of a Sikh co-worker. The following is an excerpt from her report.5

MY CROSS -CULTURAL DAY WITH ANANYA

For my cross-cultural experience I was fortunate to spend the day with Ananya, who is an IT specialist at my organization. I was invited to her home and to accompany her to the Sikh Gurdwara (temple) in East Vancouver. I wanted to embrace this opportunity not only for the experience but also because I looked forward to getting to know her. The objective of the experience was to practice mindfulness in order to increase my cultural intelligence and be more effective in a variety of cross-cultural situations. Over the weeks following my visit with Ananya, I re-examined some of my past and present experiences as well as my thoughts and opinions. I realized that despite being different, I had become desensitized and had oversimplified the influence of culture around me. I had always believed that I instinctively knew more than others because of my history of being simultaneously Canadian and Japanese but never fitting into either world. However I realized that just because I am bicultural, it does not make me an expert in operating cross-culturally.

In preparation for my day with Ananya I read to gain some basic knowledge about her culture. It was helpful to read about Indian facts and culture on the Country Insights page of the Government of Canada website and the information on the Internet about Sikhism. This information allowed me to learn appropriate behavior at the temple and to develop expectations about her home.

Some aspects of Ananya’s home were a surprise, such as how her children, who were born in Canada, respected and lived the family value system in a deep way. The family had custom-designed their current home to a duplex and laneway house so that the parents and their two adult children are able to live multigenerationally together. This is a cultural norm. We drank the chai tea that she prepared for us and talked. I learned about how she practices her beliefs through the twice-daily prayer and washing. This helps her overcome the frustrations of a bad work day. The scriptures teach to remove negative thoughts before going to bed.

At the temple my head was appropriately covered. I followed her to the women’s side of the entrance hall where we removed our shoes and washed our hands. We walked into the main hall, and I bowed when she bowed. We then accepted the Karah-parshad pudding. I became overwhelmed in the moment and did not cup both hands. I was embarrassed, but the woman dishing out the pudding gave me the slightest of smiles and demonstrated without speaking. Could this have been a smile of disapproval? I was not sure. I immediately corrected my behavior. We found a place to sit with the women, and I listened to the singing of the Gurbani while I read the English translation upon the large screen. It spoke of human frailty, and the beautiful music was both enchanting and sad.

We left upon Ananya’s signal and joined in the sharing of a meal in the Langar halls at communal tables. Did I feel uncomfortable that day? I know I attracted some attention, but (as a Japanese-Canadian) my normal is to be different in a crowd. Consistent with Sikh beliefs, I felt welcome to be there. Being immersed in this situation and operating with heightened awareness was a good reminder of what it feels like to be different. I realized that over time I had dialed down my sensitivity and have been on “cultural cruise control.” During my day with Ananya, I did work hard to observe, and it took constant attention. However I found that questioning why did not come automatically. Too many times I subconsciously answered my own questions with assumptions, which typically were based upon stereotypes. These were lost opportunities to gain a deeper understanding. When I returned home I did some more reading and was better able to appreciate my experience in the Gurdwara. I found that my retention for cultural details improved, this second time being able to put the knowledge into an experiential context. Continuous learning is important to increasing cultural intelligence.

A key takeaway from my experience is to be more mindful of the needs of my co-workers when we converse about an issue. Often if a person was frustrated at work, I had, over time, developed a script. I listened to identify the problem and honed in on the impact to the individual whom I assumed was looking for a resolution. This is the approach that is common in individualistic cultures. However on my day with Ananya, I learned I need to be mindful that some people have great concern or greater concern about the group than others. In order to satisfy their need for resolution, I must remember to address issues at multiple levels, particularly for those with a collectivist orientation.

This bicultural student’s experience with her colleague is a good example of mindfulness in action and the development of cultural intelligence. Her immersion into a culturally different situation showed her how often she had operated on cultural cruise control, and her description of the situation shows acute attention to the behavior of those who are culturally different from her, as well as to the context. As this case shows, you can find cross-cultural interactions in your own backyard as well as abroad. These learning experiences can translate very directly to participants’ daily lives at home or in the workplace.

FOREIGN EXPERIENCE AND EXPATRIATE ASSIGNMENTS

One of the most challenging ways of confronting cultural differences is living and working in a foreign country for a temporary period.

BUT I AM CHINESE!

Changying, a Chinese American with a master’s degree in international business who is fluent in Chinese, had taken an assignment in China with a multinational firm. She felt she would be a bridge between the firm’s Chinese and American managers, but she was surprised to find that she had misunderstood the environment. After a year she noted: “My understanding of managing effectively came primarily from trial and error. I learned the hard way, falling on my face. But each time I fell, I’d assess what the critical learning of each incident was. When accepting an overseas assignment one must have an open mind. China has one of the highest expatriate assignment failure rates in the world, and inability to manage across cultures is the most important reason, because expatriates fail to understand the thought processes and motivation of local employees.”6

As this case demonstrates, cultural intelligence is often gained by trying out new behaviors and observing their effect, even when they don’t work out as planned. Also, the observation that understanding how local employees think is important to expatriate success cannot be overemphasized. Foreign visits and assignments require, perhaps more than any other situation, that you try to understand the behavior of others in terms of their own cultural background. They offer opportunities for intense experiential learning. If, like most people, you have had very little cross-cultural training before going overseas, you will have to adjust on the fly.

In foreign experience, unlike work in multicultural teams, we are typically focused on the single culture in which we are immersed, and the experience consequently tends to be intense and emotionally charged, causing high stress levels until we adjust. When everything seems to be working against us, it is difficult to see the situation as a meaningful learning experience.

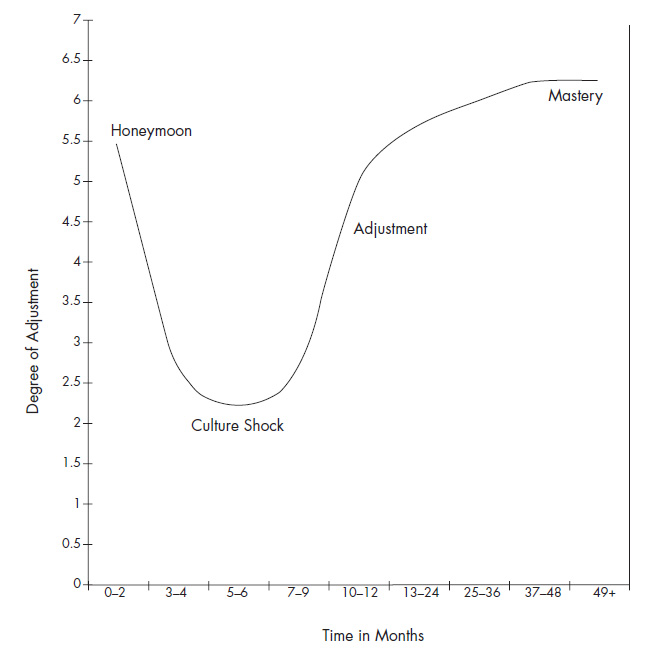

Figure 8.2 shows a model of the phases that some experts believe people go through as they adjust to a foreign environment.7 The process follows a U-shaped curve through a honeymoon period, culture shock, attempted adjustment, and then mastery. In the honeymoon stage everything is new and exciting, as it would be to a short-term tourist. In fact, most fast-moving tourists never get beyond this stage, making tourism often too shallow an experience for the development of cultural intelligence. In the culture-shock stage, the differences between what the expatriate is used to and what the new culture provides become apparent, as the individual either learns—including developing his or her CQ—or fails to learn, how to adapt. Those with high CQ get into the routines and rhythms of daily life in the new country and move eventually to mastery, while others never properly adjust.

FIGURE 8.2. The U-curve of cross-cultural adjustment

A real possibility for some people is that the adjustment is so successful and their view of the new country so positive that they lose all desire to return home. Others meet romantic partners in the new environment, and the couple must make the tough decision about which of them will make the other’s country home.

BREAKUP IN BEIJING

For Dublin natives Jonathan and Julie Henderson, Jonathan’s move from his corporate position in Amsterdam to Regional Vice President for Asia seemed like a wonderful opportunity: a big promotion and salary raise, the chance for the couple and their children to experience Asian culture, a home in a luxurious expatriate development with good schools for their two children, a minimum three-year contract with a guaranteed subsequent job in South America, and a part-time job for Julie in Beijing with the HR consultancy she had worked for in Europe. It was a chance the adventurous Hendersons were up for. They traveled to China with high hopes.

But two years later it seemed that everything that could go wrong had gone wrong. First of all there were minor problems: the move had not been handled well by HR at Jonathan’s company, there were unexpected expenses due to Chinese bureaucracy, and communication was either too indirect or was hampered by poor English skills among some of the locals in Jonathan’s organization. Then there were contextual discomforts: high air pollution, poor sanitation, difficulties in sourcing food secure from contamination, living in a compound cut off from proper cultural experience and having the children gawked at by locals whenever they went out. In addition, Jonathan’s job required much more travel than he had expected. Julie, left at home with an ayi (maid) to look after the family, felt under increasing stress. This was compounded when their two sons each suffered major medical problems and she realized the frightening inadequacy of local medical resources. She even had to travel with one child to Hong Kong to ensure adequate treatment. And the children said they didn’t like China; they couldn’t relate to the locals, and they missed their Irish relations, who they had seen a lot when they were in Amsterdam. Their unhappiness upset Julie further. When did I sign up for this? she thought.

Two years into the assignment, Julie went to her hometown, Dublin, for a work-related conference, where she also met up with her Irish family. In Dublin, the children enjoyed a happy reunion with their grandparents and other relations, and Julie was unexpectedly offered the job of her dreams, with a global consulting firm. And in her own home town! Time for the family to repatriate, surely? But Jonathan was contractually obligated to continue in his job in Beijing for another year and did not want to break his link with the company and perhaps jeopardize his entire career. Reluctantly, the family agreed to split up for at least the next year, Jonathan remaining in Beijing while Julie re-settled in Dublin with the children.8

This case shows that cross-cultural issues may be only one of many factors affecting expatriate assignments that may cause problems for assignees, their organizations, and their families. As a result, many organizations operating internationally are re-thinking their whole approach to such assignments, with alternatives including shorter stays, flying visits, and more employment of locals. On the other hand, some expatriates find living overseas a very positive, sometimes life-changing experience.

As the case also shows, cultural intelligence may be important for the whole family. If you want your children to grow up with a high CQ in a world that will increasingly value it, why not give them a taste of international experience while they are still young and flexible enough to make the most of it? They will need support and guidance, but gaining cultural intelligence as a family will be a great experience.

For those in international organizations, employers can assist adjustment to overseas postings by providing appropriate training. There is evidence that cross-cultural training assists with overseas adjustment, relationships with host nationals, and employee performance. However, some organizations believe cross-cultural training is not effective and do not provide it. If you have been given this book by your company as part of an education program, it is a sign that the company is giving some thought to these important issues. If your staff has cross-cultural issues, consider giving copies to them.

DOING IT HER WAY

Margaret is English. She has always enjoyed travel. At nineteen, she traveled for two years in Europe. She funded her travel mainly by working in Greece as a bartender and even gained supervisory experience in a restaurant. Her European experience sparked an interest in both history and in business. So on her return to the UK, she went to university to study history and economics.

When she finished the degree, Margaret decided on a career in teaching. But she first wanted to travel again, so she gained a place with JET (Japanese Exchange Teaching)—teaching English to adults in Japan, an opportunity she thought would be culturally, linguistically, educationally, and financially valuable to her. Her assignment carried a two-year contract.

Margaret settled well into the JET work in Osaka, where she was soon approached by a local government organization wanting to hire her to set up an English-language program for its employees—an opportunity for further personal and professional development. Her students were well motivated, and this six months of additional part-time work helped Margaret to add to her savings and gave her a friendly social circle. She took trips around Japan with her adult student friends.

Margaret also had enough money and time away from teaching to do about three months’ touring per year in Asia. She traveled with an American friend, a colleague in the JET program. Meantime Mama-san and Papa-san—a café-owner couple with whom she boarded, adopted her almost as if she were their own daughter. They showed her around, taught her about Japanese ways, communicated with her only in Japanese, and gave her part-time work in the café. Margaret’s cultural learning was dramatic.

After two years, Margaret became aware that she wanted to return to Britain. She wanted to see her parents and brothers again, and she wanted to own her own home. As to her teaching career, she thought about the rudeness and poor self-discipline of British school students and compared them unfavorably to those of her polite and motivated adult Japanese students. She realized how poorly paid teachers were. She returned to the UK with some money but no real plan. She bought a small house in her home city.

She got a job as a sales rep for a company selling database solutions and soon realized that she had found her forte—selling. Then, two years ago, she was approached by a software company and took a sales job with it. The job is good but doesn’t utilize all her energy or fulfill all her interests. She aspires to start her own business. She learned a lot from Mama-san and Papa-san and the way they had turned their little Osaka café into a gold mine! But she feels she lacks skills and knowledge relating to the wider business world, so she has enrolled for an MBA. She has a business plan—to start an export-based Internet company selling British products overseas. She sees Japan as a key market and believes her understanding of the language and culture will assist her greatly.

Among the things Margaret learned overseas were the Japanese language (and a smattering of other Asian languages), patience, and what she calls “cultural sensitivity”—particularly how to interact with Asians, an ability she uses a lot with Indian and Chinese staff in her current employment. Overseas, she gained self-knowledge, self-confidence, and a broader perspective. She enhanced her cooking skills, her ability to speak in public, even her abilities in her sport, judo. And of course she now has a special interest in, and affinity for, Asia, especially Japan and its people, and good contacts there. She knows Japan will continue to be important in her life.9

Margaret’s self-initiated expatriation has not only dramatically increased her cultural intelligence, it has transformed her entire life, including her employment, her long-term ambitions, and her identity. She is now much more of a citizen of the world. In her determined internationalism, she is typical of many of today’s young people. They want to see the world. Because employment in other cultures forces us to come to grips with those cultures, young people increasingly work as they travel, and the acquisition of cultural intelligence is integrated with their career development. As one returnee from extended foreign travel put it

I have learned to look at the world around me with a childlike wonder and to drop any preconceived notions…. I have learned that just because I have grown up indoctrinated by a certain set of rules regarding how relationships and society in general work, that does not make them universally true or right.

If you are a middle-aged reader and are thinking, “Gee, I wish I had thought like that when I was young,” it’s never too late. Talk to your children about it!

ACQUIRING CQ THROUGH OVERSEAS EXPERIENCE

As shown previously, spending time living and working abroad is an important way of developing cultural intelligence. But it does not happen automatically. It requires a significant interaction with the new culture, providing the opportunity to practice mindfulness and develop cross-cultural skills. Some leading companies use global experiential programs in which high-potential employees work in multicultural groups to solve problems in developing countries. An example is Project Ulysses at PricewaterhouseCoopers.10

PROJECT ULYSSES

PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) consists of legally independent firms in 150 countries and employs more than 160,000 people (5 percent of whom are partners). Project Ulysses is an integrated service-learning program initiated by PwC in 2001. Participants are sent in multicultural teams of three or four to developing countries to work with NGOs, social entrepreneurs, or international organizations. These teams work on a pro bono basis in eight-week field assignments helping communities deal with the effects of poverty, conflict, and environmental degradation. As of 2008, 120 PwC partners from thirty-five different countries participated in the program. The overall goal of the project was to develop global leaders in PwC’s worldwide network of firms. In reporting on the leadership needs of PwC, Ralf Schneider, a PwC partner based in Frankfurt and head of global talent development said, “It was clear it was not going to be a standard business model with a standard leader. We needed to take people outside of that box.” Knowledge gained by individuals is transferred back to the organization not only by participants resuming their jobs but also through formal debriefing sessions that permit PwC to continuously refine the Ulysses model.

Examples of the project teams are the following:

Brian McCann, a PwC client service partner from Boston who specializes in mergers and acquisitions was the only U.S. member of the 2003 Belize team that included colleagues from Malaysia, Sweden, and Germany. Their mission was to work with Ya’axché Conservation Trust to evaluate the growth and income-generating potential of the eco-tourism market in southern Belize where 50 percent of the population is unemployed and 75 percent earn less than U.S.$200 a month. Brian reported that the learning experience from both a personal and a professional perspective was profound.

Dinu Bumbacea, a PwC partner from Romania, and his teammates from Thailand, Australia, and the UK worked with the Elias Mutale Training Centre in Kasama, Zambia, along with the United Nations Development Program and Africare on a strategy for economic diversification in the region. Dinu said that the experience gave him new insight into operating in a multicultural environment and team, and in dealing with the public sector.

Programs such as Project Ulysses provide cultural intelligence development opportunities combined from both multicultural teams and overseas experience. However, not everyone is fortunate enough to work for organizations with such extensive programs.

You can of course develop cultural intelligence from oversseas experience without such formal programs. However, you will need to prepare, focus, and be mindful. Every cross-cultural incident—at your work, in social life, even when shopping—will be an opportunity to reflect, to learn, and to experiment. You will need to be in the right frame of mind to acquire CQ. Why are you going overseas? What do you want from the experience? Escaping a bad situation at home or hoping for career advancement on return may not be the best motivation. Self-development, a desire for adventure, a wish to broaden your horizons and meet new kinds of people, or a sense of mission are better. They will help you to live in the here and now and to take a genuine interest in your new environment and its people.

You will need to prepare. Read all you can about the new country you are to visit and find out about its cultural background. Study the cultural dimensions we introduced in Chapter 2, and try to figure out where your new home fits in. Seek out people who have been there, and ask them about their experiences. Consider also the various personal issues involved (such as those experienced by the Hendersons in the earlier case), including potential effects on compensation, family life, social networks, lifestyle, health, career, and stress.11

In many foreign locations there are opportunities for newcomers to feel at home—restaurants and communities set up by expatriates, international hotels modeled on Western norms and standards, and even, for example in Saudi Arabia and China, compounds or housing developments designed for specific groups of foreigners. To develop cultural intelligence, you should avoid the temptation of spending all your time in these environments, which are essentially just extensions of home. Remember our advice to get out of your comfort zone, and seek genuinely local experiences.

As in the cases of the Hendersons and Margaret, the most common reason that people return early from overseas is family issues. Make sure your relationships with family members you are leaving behind are considered. Involve family members who are going overseas with you in the preparation, and support them in the adventure. It is their opportunity to acquire cultural intelligence too, and their adjustment is just as important as your own.

You will have to be self-forgiving and patient. Even with plenty of preparation, you will doubtless make mistakes. Your performance in the first year abroad is unlikely to be your best. You may sometimes need to laugh at your own inadequacies and to remember that you can learn from even negative experiences.

The future for many is not just intercultural but international. We, and our children and grandchildren, will more and more have to be able to feel at home wherever we are and to function with the ease and familiarity that is habitual to us at home. The opportunity to travel to foreign countries is precious. The investment is our time and aspirations and the energy we give to the process. Part of the dividend we receive is enhanced cultural intelligence. As we hope this book has shown, the reward will be well worth the effort.

Rules of Cross-Cultural Engagement

Last, regardless of the specific cultural context, there are several rules of engagement for interactions with others who are culturally different. Become knowledgeable about your own culture and background, its biases and idiosyncrasies, and how these are unconsciously reflected in your own perceptions and actions.

• Deliberately avoid mindlessness: expect differences in others. See different behavior as novel, and suspend evaluation of it.

• Switch into a mindful mode, becoming attentive to behavioral cues, what they may mean, and the likely effect of your behavior on others.

• Adapt your behavior in ways that you are comfortable with and believe are appropriate for the situation.

• Be mindful of responses to your behavioral adaptation.

• Experiment with adapting intuitively to new situations, and use these experiments to help you acquire a repertoire of new behaviors.

• Practice new behaviors that work until they become automatic.

Summary

Developing cultural intelligence requires experiences that involve both acquiring knowledge and applying mindfulness. Such development involves a series of stages, from simply reacting to external stimuli to proactively adjusting behavior in anticipation of changes in the cultural context. Some underlying individual characteristics support this development. Ways of developing cultural intelligence can include formal education and training, but experiential learning, for which our multicultural environment provides many opportunities, is critical. Time spent living and working overseas is an excellent way to improve cultural intelligence, but one should first know a good deal about oneself, and one should understand the phenomenon of culture shock and the process of adjustment. Practicing mindfulness enhances this ability. Following a few simple guidelines for intercultural interactions can assist in developing the ability to act competently across cultures, adding a valuable skill to your repertoire.