CHAPTER 1

Living and Working in the Global Village

I PROMISE TO TRY

Barbara Barnes, alone in her Minneapolis office, pounds her desk in frustration. She has just read an email from an irate customer, who complains that her department’s technical representative, who has been visiting the customer to correct a fault in software supplied by Barbara’s company, is not only unable to solve the problem but seems to have less knowledge of the software than the customer’s own staff. The customer’s business is being seriously disrupted. Can Barbara please send someone else, who knows what they are doing?

Worse, this is the third such incident reported to Barbara this week. It doesn’t seem to be just a single employee fouling up—the whole technical department seems unable to resolve such issues. True, the software is new and initial bugs are to be expected. But Barbara recalls that several weeks ahead of the first delivery to customers, she had a conversation with Vijay, the section manager, who is on a two-year temporary assignment from the Delhi office. She had wanted Vijay’s assurance that the technical staff would all be ready in time.

“Vijay,” she said, “we have four weeks to get everyone up to scratch. There is still time to delay the launch, but it would cost customer goodwill. Can you do it in time?”

Vijay hesitated. “It will be difficult,” he said. “Do you think it’s possible?”

“I know it’s tough,” she said. “But if anyone can do it, you can.”

Vijay smiled. “H’mmmm. In that case, we will do it.”

“Thank you, Vijay.”

He looked out of the window. “It’s snowing again,” he said. “I hate your winters. People get sick. Everything slows down.”

Now, Barbara calls Vijay to her office and explains the problem to him.

“I thought you said all the technicians would be trained.”

“Most of them have been. It is bad luck. There have been more technical issues and more staff sickness than we expected. But we can resolve this problem. I will reassign trained staff to the dissatisfied customers. And soon all the staff will be trained.”

But Barbara can’t stop the anger rising in her throat. “But Vijay,” she said. “You promised!”

Vijay doesn’t answer. He is too amazed to speak.

Did Vijay promise? Barbara is absolutely certain he did. Vijay is certain that he said only that he would try, and he pointed out the considerable difficulties. To understand the differences in perception, we have to understand cultural differences between home-grown Americans like Barbara and South Asians (Indians) like Vijay. The difference is about the context in which specific words—such as “we will do it”—are spoken. American culture stresses low-context communication; what matters is the precise meaning of the words spoken, regardless of context. In Vijay’s high-context Indian culture, communication is heavily influenced by contextual cues, which in this case included Vijay’s hesitation, his account of difficulties, and his reference to the weather. Another Indian overhearing the conversation would be clear that Vijay was promising to try but believed the task would be impossible.

Both Barbara and Vijay may have the best interests of their employer at heart, but the results of their miscommunication are potentially serious. The company has broken its trust with some of its customers. Just as Vijay is accountable to Barbara for the error, so will Barbara be accountable to her own boss for loss of customer goodwill. And, perhaps more seriously, both Barbara and Vijay may feel that they cannot trust the other again.

How did this happen? Barbara assumed too much from Vijay’s words, failed to double-check the real meaning of his communication, and therefore did not hear Vijay’s warning. Vijay likewise assumed he had made himself clear. These failures result from their lack of what we call cultural intelligence. If either of them had been able to understand and accommodate, at least in part, the other’s culturally based customs and norms, and if they had tried harder to help each other to understand their own customs, they might have been able to check out each other’s messages to ensure that they both understood the same thing.

The story of Barbara and Vijay is typical—it is a story that is enacted again and again, in different forms and in many situations around the world, as ordinary people grapple with the problem of relating to others who are from cultures where things are done differently.

Consider the following examples:

• A British company experiences inexplicable problems of morale and conflict with the workforce of its Japanese subsidiary. This seems out of character with the usual politeness and teamwork of the Japanese. Later it is found that the British manager of the operation in Japan is not taken seriously because she is a woman.

• Two American managers meet regularly with executives and engineers of a large Chinese electronics firm to present their idea for a joint venture. They notice that different engineers seem to be attending each meeting and that their questions are becoming more technical, making it difficult for the Americans to answer without giving away trade secrets. The Americans resent this attempt to gain technological information. Don’t the Chinese have any business ethics? Later they learn that that such questioning is common practice and considered to be good business among the Chinese, who often suspect that Westerners are interested only in exploiting a cheap labor market.

• In Malaysia, an old woman struggles to unload furniture from a cart and carry it into her house. Many people crowd the street, but no one offers help. Two young American tourists who are passing see the problem, rush up, and start to help the old lady. The locals on the street seem bemused by these Americans helping someone they don’t even know.

• A Canadian police superintendent’s four key subordinates are, respectively, French-Canadian, East Indian, Chinese, and Persian. How can he deal with them equitably? How can he find a managerial style that works with all of them? Should he recognize their differences or treat them all the same?

• A Dutch couple, volunteering in Sri Lanka assisting local economic development, visit a Sri Lankan couple to whom they have been introduced. Their hosts are gracious and hospitable but very reserved. The guests feel awkward and find it hard to make conversation. Later, they worry about the ineptitude they felt in dealing with the Sri Lankans.

These stories provide real-life examples of people from different parts of the world struggling with problems caused by intercultural differences. Have you been in situations like the ones above that have left you puzzled and frustrated because you simply haven’t felt tuned in to the people you have been dealing with? Do you wonder how to deal with people from other countries, cultures, or ethnic groups? If so, you are not alone; you are one of the many people attempting to operate in a new, multicultural world.

The Global Village

There are over seven billion people in the world, from many different cultures, yet we all live in a village where events taking place ten thousand miles away can seem as close as those on the next street. Whenever we read a newspaper or watch television or buy a product from the grocery store we find ourselves in this global village. We can watch a Middle East firefight as if we were there, eat tropical fruit with snow on the ground outside, and meet people from far-off places at the local mall. The following dramatic examples of globalization are familiar to almost everyone.

THE GLOBAL VILLAGE BECOMES APPARENT

In the new millennium, Westerners’ consciousness of the increasingly global society that they live in has been powerfully raised by various major crises.

On September 11, 2001, the world came to America in a new and horrifying way. The young men who flew their hijacked airliners into the great U.S. citadels of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon were citizens of the global village. They were operating in a world with a profoundly increased consciousness of difference—haves versus have-nots, Christians versus Muslims—as well as far fewer boundaries. To the terrorists, America was not a distant vision but an outrage beamed nightly into their homes through their televisions, yet only a plane-trip away. They slipped easily into the world’s most powerful nation, acquired its language, and took flying lessons from friendly, helpful locals.

The news of the attacks traveled, virtually instantaneously, to all corners of the world. Californians stared aghast at the strange horrors of the day’s breakfast show. Europeans crowded around television screens in appliance store windows. Australians phoned each other in the night and said, “Switch your telly on.” A billion viewers around the globe watched as the Twin Towers collapsed in front of their eyes.

In October 2008 people around the world again watched in horror as the morass labeled GFC (global financial crisis) spread quickly into their lives. Some of the biggest and apparently most impregnable financial institutions suddenly went out of business, crippled by multibillion-dollar debts. Flows of credit—the lifeblood of business—froze, and stock markets plunged. Firms closed down and staff was laid off. Political leaders struggled to resolve the issue by freeing up trillions of dollars for bailouts of stricken banks—a de facto reversal of their most cherished principles of free-market capitalism. Yet it was only when the world’s leaders all came together in meetings of the leading industrialized counties and developed integrated global solutions to a global problem, that the bleeding stopped and markets around the world began to stabilize. Even so, it is only now, in 2017, that many countries are beginning to put the global financial crisis behind them.

In September 2015 the photo of Aylan Kurdi, a three-year-old Syrian boy who had drowned and washed up on a beach in Turkey, shocked the world. He and his family were part of the most significant refugee crisis since the Second World War. His mother, Rehan, and five-year-old brother, Galip, also perished. Only his father Abdullah survived the perilous sea journey. The photo of Aylan brought the plight of Syria’s millions of refugees to world attention. Other refugees fled to Europe from conflicts in Libya, Afghanistan, and other countries. Despite the efforts of many governments and aid agencies, as 2015 drew to a close, the world had yet to come to grips with this massive migration. As the world’s great countries squabbled about how many each could absorb, four million refugees were registered and camped around Europe. The problems of integrating them will be massive, and they will not be only economic and political problems but also cultural.

After these events, people said, “The world will never be the same again.” They might rather have said: “The world has been changing rapidly for some time. These events have caused us to notice it.”

Such events are not just about America or Europe and the Middle East; they are global. Economic, political, legal, and cultural forces are at work that cross international boundaries, create international problems, and require international solutions. We are all involved, all of us citizens in a global world. None of us can escape that.

Forces of Globalization

As we increasingly live global lives, we are beginning to understand the importance of globalization, particularly its effects on our lives. Globalization increases the permeability of traditional boundaries, not just those around organizations but those around countries, economies, industries, and people.1

Globalization has been accelerated by many factors, including the following:

• Increased international interconnectedness, represented by the growth of international trade and trade agreements, multinational corporations, and the relocation of businesses wherever cost is lowest.

• The increased migration, both legal and illegal, particularly from less-developed to more-developed countries. In virtually every nation are many people who were born and brought up in other countries or are culturally influenced by their immigrant families.

• The ability of information and communication technology to transcend time and distance so that at the touch of a computer keyboard or a mobile phone, we can be somewhere else, thousands of kilometers away, participating in events and changing outcomes there.

Until recently, only a few very large multinational organizations were concerned with foreign operations. Now even very small organizations may be global; indeed, small and medium-sized organizations, which increasingly can survive only if they export their products, account for a growing share of global business.

Because of globalization, the environment of organizations is now more complex, more dynamic, more uncertain, and more competitive than ever before. These trends are unlikely to reverse or decrease. Tomorrow’s managers, even more than today’s, must learn to compete and work in a global world.

Globalization of People

Globalization affects managers, employees at all levels, customers, and indeed everyone! It brings about interactions and relationships between people who are culturally different. As organizational members, as tourists, and as members of networks and communities that have “gone international,” we travel overseas among people from other cultures, telephone or Skype them, correspond with them by e-mail, and befriend them on Facebook. Even in our home cities, more and more of our colleagues, clients, and even the people we pass in the street are from cultures that are different from our own.

This globalization of culturally different people creates a major challenge. Unlike legal, political, or economic aspects of the global environment, which are observable, culture is largely invisible and is therefore the aspect of the global context that is most often overlooked.

The potential problems are enormous. Even people from the same culture often lack interpersonal skills. When interpersonal interaction takes place across cultural boundaries, the potential for misunderstanding and failure is compounded.

The conclusion is clear. You are a member of the global community, even if you are not conscious of it and even if you have never done business abroad or even traveled abroad. You may never have gone around the globe, but the globe has come to you. Any organization you work for will most likely buy or sell in another country, or will be influenced by global events. You will increasingly have to interact with people from all parts of the globe.

Here is a story about two global people. One is an international migrant who is trying to find a new life in a very different place. The other is a manager who has never left her own country.

THE JOB APPLICANT

In California, a human-resources manager sits in her office. She is interviewing candidates for factory work. Suddenly a dark-skinned young man walks in without knocking. He does not look at the manager but walks to the nearest chair and, without waiting to be invited, sits down. He looks down at the floor. The manager is appalled at such graceless behavior. The interview has not even started, and even though the jobs being filled do not require social skills, the young man is already unlikely to be appointed.

Observing this scene, most Americans and Western Europeans would understand why the manager felt as she did. The man’s behavior certainly seems odd and disrespectful.

But suppose we tell the manager more about the young man. He was born and brought up in Samoa and only recently immigrated to the United States. Samoans have great respect for authority, and the young man sees the manager as an authority figure deserving of respect. In Samoa you do not speak to, or even make eye contact with, authority figures until they invite you to do so. You do not stand while they are sitting, because to do so would put you on a physically higher level than they are, implying serious disrespect. In other words, according to the norms of his own cultural background, the young man has behaved exactly as he should. The human resource manager, based on her own culture, expects him to greet her politely, make eye contact, offer a handshake, and wait to be invited to sit down. In doing so, she is being unfair not only to candidates who operate differently, she is also reducing her company’s opportunity to benefit from people with other cultural backgrounds. As an employer of Samoans and other ethnic and cultural minorities, she would benefit from exposure to Samoan customs and training in cross-cultural communication. Of course, if the company employs the man, he may have to learn appropriate ways of interacting with Westerners. Both would benefit from reading this book!

We are all different, yet we often expect everyone else to be like us. If they don’t do things the way we would do them, we assume there is something wrong with them. Why can’t we think outside our little cultural rulebooks, accept and enjoy the wonderful diversity of humankind, and learn to work in harmony with others’ ways?

The characters in the cases we have provided so far—Barbara, Vijay, the human-resources manager, and the young Samoan man—are all, perhaps inadvertently, playing a game called Be Like Me. Do it my way. Follow my rules. We all tend to play Be Like Me with the people we live and work with. And, when the other party can’t, or doesn’t want to be like us, we—as do the characters in these cases—withdraw into baffled incomprehension.

Intercultural Failures

Many of us fail in intercultural situations in all sorts of ways, such as the following:

• Being unaware of the key features and biases of our own culture. Just as other cultures may seem odd to us, ours may be odd to people from other cultures. For example, few Americans realize how noisy their natural extroversion and assertive conversation seem to those whose cultures value reticence and modesty. Similarly, people from Asian societies, where long silences in conversations are considered normal, do not realize how odd and intimidating silence may seem to Westerners.

• Feeling threatened or uneasy when interacting with people who are culturally different. We may try hard not to be prejudiced against them, but we notice, usually with tiny internal feelings of apprehension, the physical characteristics that differentiate them from us.

• Being unable to understand or explain the behavior of others who are culturally different. What motivates us is often very different from what motivates the behavior of people from other cultures. Trying to explain their behavior in terms of our own motives is often a mistake.

• Failing to apply knowledge about one culture to a different culture. Even people who travel internationally all the time are unable to use this experience to be more effective in subsequent intercultural encounters.

• Not recognizing the influence of our own cultural background. Culture programs our behavior at a very deep level of consciousness. Behavior that is normal to us may seem abnormal or even bizarre to people from other cultures.

• Being unable to adjust to living and working in another culture. Anyone who has lived in a foreign culture can attest to this difficulty. The severity of culture shock may vary, but it affects us all.

• Being unable to develop long-term interpersonal relationships with people from other cultures. Even if we learn how to understand them and communicate with them a little better, the effort of doing so puts us off trying to develop the relationship any further.

In all of these examples, stress and anxiety are increased for all parties, and the end result is often impaired performance, less satisfaction and personal growth, and lost opportunities for our organizations.

Ways of Overcoming Cultural Differences

If these are the symptoms, what is the cure? How can we ordinary people feel at home when dealing with those from other cultures? How can we know what to say and do? How can we pursue business and other relationships with the same relaxation and synergy that we experience in relationships with people from our own culture?

EXPECTING OTHERS TO ADAPT

One way of trying to deal with the problem is to stick to the Be Like Me policy and try to brazen it out. If we come from a dominant economy or culture such as the United States, we can reason that it is for us to set norms and for others to imitate us.

You may think there is something in this. First, a dominant culture may win in the end anyway.2 For example, the English language is becoming the lingua franca of global business and education, and it is increasingly spoken in business and professional interactions all over Europe and in large parts of Asia. Second, many people believe that different cultures are converging to a common norm, assisted by phenomena such as mass communication and the “McDonaldization” of consumption.3 Eventually, they argue, the whole world will become like the United States anyway, and its citizens will think, talk, and act like Americans. Many cities around the world already mimic New York, with the same organizations, brands, architectural and dress styles: why resist the process?

In fact, the evidence in favor of cultural convergence is not compelling. Convergence is probably taking place only in superficial matters such as business procedures and some consumer preferences.4 Also, such convergence robs us of the great gift of diversity and the novel ways of thinking and working that it brings.

UNDERSTANDING CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

Can we solve the problem of cultural differences and seize the opportunity they create simply by learning what other cultures are like? Do we even know, in any organized way, what they are like?

Information about other cultures is easily accessible. Cultural anthropologists have researched many of the cultures of the world and cultural differences affecting specific fields, such as education, health, and business, have also been explored.5 This information has been useful in establishing the behavior or cultural stereotypes of many national cultures, and provides a starting point for anticipating culturally based behavior. Understanding cultural differences between countries and how those differences affect behavior is a first step toward gaining cultural intelligence. This book provides some basic information on these matters.

However, this basic knowledge is only the beginning of the process of changing cultural differences from a handicap to an asset. Even at their best, experts on cultural difference, who say things such as “Japanese behave in this way and Americans in that” can provide only broad generalizations, which often conceal huge variances and considerable subtlety. A country may have, for example, religious or tribal or ethnic or regional differences, or forms of special protocol.

The laundry-list approach to cross-cultural understanding attempts to provide each individual with a list—“everything you need to know”—about a particular country. Such lists often attempt to detail not only a country’s key cultural characteristics but also regional variations, customs to be followed, speech inflections to use, expressions and actions that might be considered offensive, and functional information on matters such as living costs, health services, and education. Tourists and travelers can buy books of this type about most countries, and some companies take this approach to preparing employees and their families for foreign assignments.

Laundry lists have their place, but they are cumbersome. They have to document every conceivable cultural variation, along with drills and routines to cater for them. For an expatriate, this intensive preparation for a single destination may be appropriate, but for most of us, our engagement with other cultures involves a less intensive interaction with a variety of cultures. If we travel to half a dozen countries, entertain visitors from a variety of places abroad, or interact with a large range of immigrants, must we learn an elaborate laundry list for each culture? If we are introduced to culturally different people without warning and have no laundry list readily available, how can we cope? Even in our own country we may be introduced to a new co-worker whose culture we haven’t encountered before.

Furthermore, laundry lists tend to be dry and formal. The essence of culture is subtler, is expressed in combination with the unique personality of each individual, and is hard to state in print. Formal and abstract knowledge needs to be supplemented by, and integrated with, experience of the culture and interactions with its people. Learning facts is not enough.

BECOMING CULTURALLY INTELLIGENT

A third approach to the problem is to become culturally intelligent.6

Cultural intelligence means being skilled and flexible about understanding a culture, interacting with it to learn more about it, reshaping your thinking to have more empathy for it, and becoming more skilled when interacting with others from it. We must become flexible and able to adapt to each new cultural situation with knowledge and sensitivity.

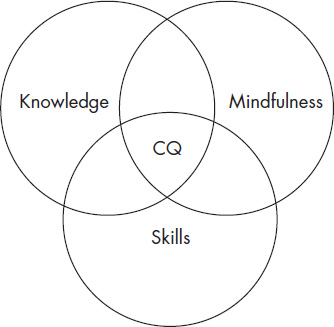

Cultural intelligence consists of three parts.

• First, the culturally intelligent person requires knowledge of what culture is, how cultures vary, and how culture affects behavior.

• Second, the culturally intelligent person needs to practice mindfulness, the ability to pay attention reflectively and creatively to cues in the situations encountered and to one’s own knowledge and feelings.

FIGURE 1.1. Components of cultural intelligence (CQ)

• Third, based on knowledge and mindfulness, the culturally intelligent person develops cross-cultural skills and becomes competent across a range of situations, choosing the appropriate behavior from a repertoire of behaviors that are correct for a range of intercultural situations.

The model in Figure 1.1 is a graphic representation of cultural intelligence.

Each element in Figure 1.1 is interrelated with the others. The process of becoming culturally intelligent involves a cycle or repetition in which each new challenge builds upon previous ones. This approach has the advantage over the laundry-list method that, as well as acquiring competence in a specific culture, you simultaneously acquire general cultural intelligence, making each new challenge easier to face.

You have probably heard of the psychologists’ concept of intelligence and its measure, the intelligence quotient (IQ). More recently has come recognition of emotional intelligence, the ability to handle our emotions, and its measure, the emotional intelligence quotient (EQ). Cultural intelligence (or CQ) describes and assesses the capability to interact effectively across cultures.7

In the chapters that follow, we present a road map for developing your cultural intelligence by addressing its three elements one by one.

In Chapter 2 we examine the necessary information base, which includes a secure knowledge of what culture is and is not; its depth, strength, and systematic nature; and some of the main types of cultural differences. This provides a good basic set of tools to give one confidence in any cross-cultural situation.

In Chapter 3 we consider how observation of the everyday behavior of people from different backgrounds can be useful in interpreting the knowledge introduced in Chapter 2. Most people operate interpersonally in “cruise control,” interpreting their experiences from the standpoint of their own culture. We develop the idea of mindfulness8—a process of observing and reflecting on cross-cultural knowledge. Developing mindfulness is a key means of improving cultural intelligence. We then outline how knowledge and mindfulness lead to new skilled behavior. By developing a new repertoire of behaviors, you can translate the understanding of culture into effective cross-cultural interactions.

Cultural intelligence is not difficult to understand but is hard to learn and to put into practice on an ongoing basis. It takes time and effort to develop a high CQ. Years of studying, observing, reflecting, and experimenting may lie ahead before one develops truly skilled performance. Because becoming culturally intelligent is substantially learning by doing, it has useful outcomes beyond the development of intercultural skills. In addition, new cultures are intriguing: learning how to live or work in them or to interact with their people can be fun, with possibilities of new insights, new relationships, and a new richness in your life. This book is the place to start on this journey.

Summary

This chapter describes the forces of globalization that are dramatically changing the environment not just for global managers but for everyone. We are all becoming global participants in our organizations; even those who stay in their own countries have to think in global terms. The essence of being global is interacting with people who are culturally different. Culture is more difficult to deal with than other aspects of the environment because much of how culture operates is invisible. Although we know much about cultures around the world, this knowledge is only the starting point to becoming culturally intelligent. Cultural intelligence involves understanding the fundamentals of intercultural interaction, developing a mindful approach to them, and building a repertoire of cross-cultural behaviors suited to different intercultural situations. For everyone living and working in today’s global environment, interacting effectively across cultures is now a fundamental requirement.