You may not recognize terms like “phishing” or “spam,” but we guarantee that you’ve been a victim of them a thousand times over. Throughout this book, we’ve covered many different forms of cyber crime, some of which have serious implications to your own personal safety. But there’s an entirely different category of cyber crime that can impact you on many other levels—by consuming your time and Internet bandwidth with what is virtually “junk mail”; by scamming innocent victims out of a lifetime of savings; by duping you into visiting misleading websites so your passwords can be stolen. We’ve become so accustomed to these daily intrusions that we sometimes forget that they are still crimes!

As a consumer, you need to recognize these crimes so you can prevent becoming a victim. These types of “daily nuisance” crimes continue to proliferate because there are still plenty of people who will, unwittingly, fall victim to them. The more you know, the better armed you are.

Phishing occurs when fraudulent emails that appear to be from a legitimate source are sent in an effort to obtain sensitive information from a user. Phishing is actually a form of online identity theft in which the recipient is “tricked” into providing personal information through a variety of means. Besides the fact that phishing bilks the victim out of money, many indirect losses are also associated with phishing, similar to identity theft—the cost to consumers to repair their credit and replace their accounts, the loss of trust in online financial transactions, and so on.

Phishing targets many kinds of confidential information, including usernames and passwords, bank and credit card account information and passwords, social security numbers, birth dates, as well as “secret question” information, such as your mother’s maiden name or a pass phrase.

The costs of phishing to consumers and businesses have been mounting. In the year ending in August 2007, 3.6 million adults in the U.S. were successfully defrauded by phishing emails at a total cost of $3.2 billion, according to Gartner Research. That’s a disturbing jump from the 2.3 million users who lost $2.9 billion in 2006.

Phishing attacks are most often perpetrated by organized crime. It is a misconception that these are amateur attacks. It is believed that most phishing attacks come out of Russia. These underground groups have the ability to “virtually” move their operation overnight, thereby thwarting law enforcement’s efforts to shut them down.

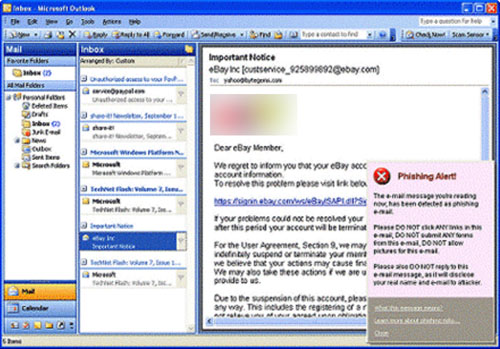

One of the most common forms of phishing is the “call to action” (see Figure 11.1). We’ve all received those doom emails with “Security Alert—Unauthorized Transaction” emblazoned on them. They advise us that our accounts have somehow been compromised and offer a link within the email itself to log into the account to verify our information.

Other types of “call to action” phishing attempts include the following:

• A claim that a new service is now available at a financial institution with a hyperlink in the message to check it out, but you must hurry because it is a limited-time offer.

• Notice of a fraudulent charge or change to your account with a link within the email.

• An invoice for merchandise not authorized by you with a link in the email to cancel or dispute the order.

• A statement that the account is somehow at risk—“Security Alert” or “Danger, Danger”—with a link to the account to correct the situation.

• A statement that there is some problem with your account and a request for you to visit the account. A link is provided within the email.

All “call to action” phishing attempts want you to do the same thing—click the link, or “hyperlink,” within the email message. However, the link actually goes to a fake website where the bad guys secretly capture your username and password for their own use.

The link may look legitimate, but you can’t go by that. The link itself could read “Children’s Fun Time” but really direct you to a porn site. In the case of a bank or credit card, the link could read “USABank” but go to a fake website that looks like the USABank site. The point is never click a link within an email even if it looks absolutely legitimate. If the email is from your bank, eBay, or PayPal, open up a separate Internet session and type the address in the address bar. Do not click the link in the email.

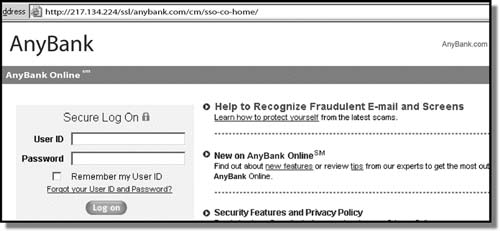

Look at the image in Figure 11.2. It looks like a legitimate link. It even has a “Secure Log On” message as well as a warning about recognizing fake emails. However, it is fake! How do you know? Because the correct Internet address (up on the top line) for AnyBank is www.anybank.com, not http://217.217…. Those numbers before “anybank.com” are a good indicator that this is a phishing attempt. Do not click hyperlinks within emails!

Here’s a new twist on phishing we’ve seen recently. Imagine getting an email from someone you know advising you that another mutual acquaintance is trapped in a foreign country and urgently needs cash to get back home. That’s exactly what happened in Fairbanks, Alaska recently when people began receiving email from the current director of a local council on aging stating that the former director had been in Africa and was in “desperate straits” because she had misplaced her bag with her money, passport, and valuable documents. When the current director tried to access her Yahoo! email account (which had previously been under the former director’s name), she realized her password had been changed. That’s when the phone began ringing from people asking about the former director’s plight and where they could send the money. Her email account had been taken over by the phishers, who used it to send out the fake warnings about the former director.

Someone finally faxed the director a copy of the email they had received, laden with typos and misspellings, along with instructions on where to send money via a MoneyGram or Western Union. The FBI is currently investigating this case, but it points to a much more personalized way of scamming people of their money.

Some of the most offensive versions of phishing scams are the ones that disguise themselves as charitable organizations seeking donations for victims of natural disasters. This was huge in the aftermath of 9/11, and we continue to see them crop up in the wake of every other disaster—earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis, floods, and so on. Ignore emails that purport to be from charitable organizations and go directly to reputable charity organizations such as the Red Cross (www.redcross.org).

A common misconception is that all phishers gain access to accounts in order to fraudulently run up credit cards and buy expensive merchandise with the account information. This is actually not typical. A phisher can garner access to thousands of credit card and bank account usernames and passwords in a relatively short span of time. They want this information to resell to others in the underworld of cyberspace. That is how they make their money.

We’re always fascinated with how quickly technology evolves. Unfortunately, so are the bad guys. It didn’t take them long to figure out if they couldn’t scam you online, they could scam you over the phone. Thus began the concept of vishing, or voice phishing. Vishing is very much like phishing except it uses phones as its medium for carrying messages.

Vishing is no different from phishing in that it is a cleverly disguised method of obtaining your PII (personally identifiable information). Common schemes are to notify you that your bank account was breached, suspended, deactivated, or terminated. You are given a number to call to correct the situation. When you call that number, a legitimate-sounding welcome message is played and then you are prompted to provide your account number and password or PIN.

Many times the vishers either infiltrate messaging services to obtain legitimate phone numbers, hack into financial institutions to obtain phone numbers, or as a last resort, use speed dialers that can dial combinations of numbers very rapidly.

Vishing messages can be sent either by voice or by text message, but they all have the same goal in mind—to get you to cough up your account information. Don’t be fooled! If you think your account may be compromised, use the 800-number on the back of your credit card or on your statement as the callback number. That number is legitimate. And as always, remember this: No legitimate business will ever ask you for your password or PIN over the phone!

A recent trend has been to combine both phishing and vishing attacks. We are aware of several recent cases whereby potential victims were sent what appeared to be a legitimate survey by a credit union with the promise of $20 to all those participating. As always, the phishing attempt required a credit card number to credit the $20. The next day, a new email was launched warning that the survey was fraudulent and that the user’s account had been temporarily suspended as a result. In order to reactivate their accounts, victims were instructed to call an 800-number. When they called, they were asked to provide their credit card number and PII (personal information such as mother’s maiden name, which thieves can use to answer security questions). Having the PII makes the credit card much more valuable because it authenticates the credit card number. It also gives the thieves the ability to open up additional accounts using the victim’s information.

We will never cease to be amazed at the creativity these criminals employ in trying to add a sense of legitimacy to their fraudulent schemes. Almost the reverse of the case just mentioned, the FBI recently warned of another scheme whereby text messages were sent to cell phones claiming that the recipient’s online bank account had expired. The message instructed recipients to renew their online bank account, and they were given a specific phone number to do that. Of course, when customers called, they were greeted with a welcome message so that everything would appear authentic. They were then asked for their account numbers and PII. The twist on this scheme is that customers also received an email with a stern warning advising them to be careful of fraudulent schemes and reminding them never to provide sensitive information when requested in an email!

There are many forms of vishing, just like there are many forms of phishing, but the one thing that remains consistent is that the perpetrators will always seek out your personal information and account information. Do not give it out!

Like any other situation, if you receive a notification from any bank that your account has been closed, suspended, or misused, use the 800-number on the back of your credit card or the number on your account statement to verify this information. Always remember that you are only safe if you are initiating the call using what you know is a legitimate number. If you receive a call, it could be from anyone, so act cautiously. We’ve already shown how easy it is to spoof or fake Caller ID. Any professional business will not mind if you ask to verify the legitimacy of a phone number.

In an ironic twist, on June 6, 2008, the IC3 (Internet Crimes Complaint Center), a collaborative program between the FBI and the White Collar Crimes Bureau, released a media alert advising consumers that their own names were being used in an email scheme containing fraudulent refund notifications. The players who thought up this doozey of a scheme sent out emails purporting to be from IC3, claiming that refunds were being made to victims of Internet fraud. They used the IC3 logo while promising thousands of dollars to be sent via the “Bank of England,” as long as the victim signs a “fund release order,” which of course would require bank account information. IC3 asks that victims of this email scam file a report at—you guessed it—www.ic3.gov.

Pharming occurs when a fake website is set up that appears identical to a real website, but carries a payload of malware (malicious software). The malware could be used to deliver a computer virus, capture every keystroke you type, or install software that will allow someone else to have remote access and control over your computer.

This type of attack used to appear only on the seamier side of the Internet—porn sites and the like—but recent studies show a proliferation of pharming attacks on even very legitimate websites, including government sites.

We have experienced this phenomenon ourselves when following legitimate web links through a browser to municipal and government websites.

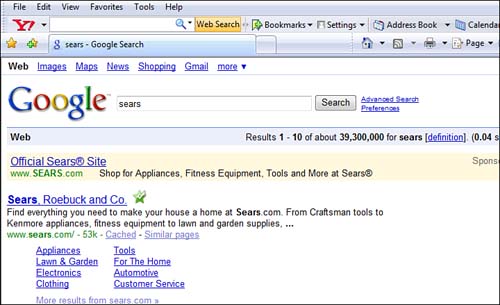

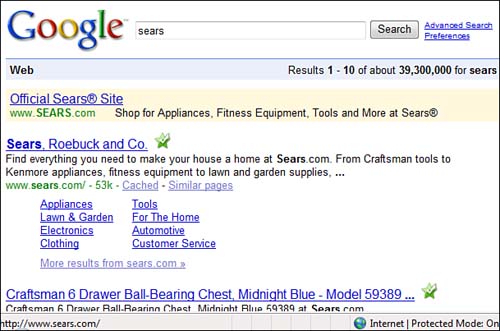

With as fast as everyone clicks the results of a search engine, it’s almost impossible to verify that every link is legitimate. However, one way to tell is to hover the mouse over the website link. If the link is to Sears, for example, the address that pops up should be www.sears.com.

When you hover your mouse over any search engine result (such as the result of a search for “Sears, Roebuck and Co.”), look down at the very bottom of your screen (see Figure 11.3). The Internet address, or URL (Universal Resource Locator), should go to http://www.sears.com (see Figure 11.4). It should not go to http://123.sears.com, for example. If it does, this may be a pharmed site!

Your best bet for avoiding pharmed sites is to type the address for the location to which you want to go (such as www.sears.com) directly in the browser address bar. Use the hover technique and verify that the link is actually legitimate. “AnyBank” should be www.anybank.com, not www.secure.anybank.com. Be suspicious of any link that begins with a prefix other than the actual name of the site you are visiting. It’s not unusual to have different things appear after the name, but the general naming convention should be www.companyorsitename.com.

Spam is that annoying email that clutters your inbox offering great deals at Canadian pharmacies, “enhancement” drugs, and access to porn sites, among many other variants. It’s more than just annoying—sometimes it’s a veiled phishing attempt, and other times it contains nasty malware that will infect your system. The technical term for spam is unsolicited commercial bulk email. The frequently used term is junk email.

The first known spam was actually sent back in the spring of 1978 by an energetic marketing specialist from a technology company when the Internet was still in its infancy. In his zest to tell everyone about a new computer system his company had developed, the marketing man, named Gary, turned to what was then known as ARPAnet, the Internet in its earliest stages. So small was the Internet then that only a few thousand people were active on it. All of their names were conveniently kept in a single directory, if you can imagine that. Gary selected about six hundred of those names and sent a message: “We invite you to come see our new system…”. The reaction was strong, immediate, and nearly all hostile. “This was a flagrant violation of the ARPAnet,” one recipient wrote. Gary was harshly reprimanded by the system administrator. Nevertheless, his company sold more than 20 of the million-dollar computer systems. Thus the first spam was launched.

Now fast-forward 30 years later: Current estimates are that a staggering 120 billion spam messages are sent out each and every day (source: The 2008 Internet Security Trends Report). From 600 annoying emails to 120 billion in 30 years—that’s how fast spam has grown.

People understand what spam is. They understand how annoying it is, but few understand how anyone could profit from spam. “I always delete spam,” everyone says. So how do they make money from it?

For every million people who delete spam, many open it and respond. Consider the sheer volume of 120 billion spam emails a day. It doesn’t take much to realize that given the enormity of that number, several thousand people could reply a day. When someone does respond, their email address and personal information is recorded and resold—for a very nice profit—to other companies. For example, someone who has expressed an interest in a mortgage is likely to have their information resold as a lead to other mortgage companies. The people who pass the information along are called “leads generators” or “affiliate marketers,” and they make a tidy profit from it. For each final lead that includes the interested party’s information as well as contact information, a leads generator can earn anywhere from $10 to $20.

Although many companies that use marketing information say they have a “zero-tolerance” policy for spam, they mean they don’t actively send spam. It does not mean they do not profit from spam, as long as they purchase your name and information from a leads generator whose source is spam. That is not to say that there aren’t legitimate leads generation companies, because there are, but many times the leads from spam travel through so many layers that it’s impossible to tell the legitimate ones from the not-so-legitimate ones. It is not uncommon for someone on the bottom of the leads generation food chain to receive less than a dollar to forward along someone’s email, but again, the sheer volume of spam means that even these bottom feeders are making a tidy profit.

Spam has moved beyond being a simple annoyance to being a potential threat, considering that in 2007, more than 83% of spam contained a URL or web address within the body of the spam message (source: 2008 Internet Security Trends Report). This means that more and more spam contains malware (malicious software) that can install keystroke loggers and spyware on your system.

Not only can spam carry a payload of malware, it wastes an enormous amount of network bandwidth that could go for much more valuable pursuits. It is not unusual for corporations to block 95%–99% of all incoming mail because it is identified as spam. That’s a lot of wasted network bandwidth.

Beyond those dangers, think about how much time is wasted just going through hundreds of email getting rid of the spam. Commercial products are available that can block spam, and many corporations employ them. However, spam-blocking lists literally change overnight, and it’s almost impossible to keep up on all the sources of spam. The end result is that thousands of hours are wasted every year by consumers and workers trying to wade through the list of junk mail that fills their inboxes.

Spam has also been linked with many dangerous scams, such as tainted prescription drugs sold on the black market.

Groups such as APEWS (Anonymous Postmaster Early Warning System; www.apews.org), Spamhaus (www.spamhaus.org), and SpamCop (www.spamcop.net) actively attempt to catalog known sources of spam and block them. These spam vigilantes work independently not only to reduce spam but identify sources of spam.

People often scratch their heads when trying to figure out how spammers got hold of their email address in the first place. Did you know that computer programs called “spiders” sweep the Internet and automatically cull through millions of web pages looking for email addresses? Because most email addresses use the format name@webprovider.com, it is easy for these spiders to know when they have a hit and to harvest that address.

Notice we said “reduce”. It is virtually impossible to rid yourself entirely of all spam, but you can certainly limit the amount you get by following these steps:

• Never reply to spam.Before you fire off that nasty email to the spammer to tell him to stuff it, stop before you press Send. All you will accomplish by doing this is to confirm that your email address is valid. That’s what he wanted in the first place. Just delete the email.

• Turn off your “preview” feature in your email account.Microsoft Outlook, by default, opens up all email in a preview pane. Shut off this feature so you don’t open any emails until you’ve had a chance to screen them. Just opening an email can deliver a payload of a virus onto your computer system. Instead, just delete the spam email.

• Never click any links contained within spam.It is very possible they contain malware. Just delete the spam.

• Disguise your email address on the Web.Those spam spiders will have a much harder time if your email address is written out as “user at anywhere dot com” rather than [email protected].

• Stop forwarding emails to your friends.“If you send this back and to eight other friends, something wonderful will happen within the next hour,” says the email from your best friend. If you reply and forward the email along, you’ve just managed to harvest eight more email addresses on behalf of spammers. We know, these emails are often entertaining, but by forwarded them you’re just giving up your friends’ email addresses to spammers. Just delete the spam instead.

It’s bad enough that your inbox is filled with spam and junk email, but in a recent twist, users are getting death threats delivered via spam. As you know, spam can be customized to include your last name, first name, even your address. These emails, which often have the subject line “BE MORE CAREFUL,” contain frightening language. Oftentimes, the sender claims that they have been solicited to kill the recipient. As we said, it’s not unusual for the recipient’s name and address to be included to add veracity to the claim.

Anyone would be frightened to receive this type of email. The sender may claim they have been watching the victim for some time or that they even have photos of him or her. The message “We have watched you go in and out of 123 Main Street” would be disturbing to anyone. The email usually goes on to say that the sender is willing to “spare” the recipient’s life for a price, or sell a recorded copy of the actual “murder for hire” solicitation to the recipient. Of course, the recipient is warned not to contact authorities. The entire scam is an attempt to extort not only your money, but your private bank and credit card account information.

It most certainly is. Ask Robert Alan Soloway, dubbed one of the “Top Ten Spammers”. He just recently plead guilty to charges of fraud, email fraud (under the CAN-SPAM Act), and failure to file an income tax return. Prosecutors claim that Soloway sent more than 90 million emails in 3 months from just two of the many servers he used around the world. Soloway is purported to have made over a million dollars by sending out millions of junk emails. He faces a maximum sentence of 20 years for fraud, 5 years for email fraud, and 1 year for not filing an income tax return.

The acronym CAN-SPAM stands for “Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing Act,” which belies its roots. The law became effective on January 1, 2004. It had several purposes, one of which was to prevent pornography from being disguised in email with the subject line “Family Photos” or “News from Tom”. The CAN-SPAM Act requires that any solicitations with adult content be clearly marked as such in the subject line.

The act has been controversial in that it does not seem to have done much to curtail the threat of spam. Although the CAN-SPAM Act has undergone periodic revisions as recently as July 2008, its effectiveness remains to be seen.

Ever get a text message on your cell phone telling you to apply for a job or that you’ve been selected for a special promotion? If so, then you’ve been “text spammed”. What makes these messages so bothersome is that they are lengthy and try to install downloads. What’s more, if you pay per text message, then you have to pay to be spammed! And by the way, phone spam is illegal as well.

Cell phone companies claim they are trying to combat this latest annoyance. Verizon Wireless says they block more than 200 million spam messages per month. In fact, the FCC voted to ban all unauthorized commercial text messages to cell phones and pagers, and the Telephone Consumer Protection Act prohibits autodialed and prerecorded calls to cell phones. This Act also applies to text messages—but good luck trying to report a text spam to the local police.

The best recourse you have when you do get text spam is to report the violation to your cell phone carrier. They may reverse the charge when you report it, but even more important, they’ll want to know about it in order to put in better blocks. Some cell phone providers also allow you to block text messages that are generated by computers—the source of most cell phone spam.

In May of 2008, the social networking site MySpace won a $234 million judgment against two prominent spammers in what may be the largest anti-spam award ever.

MySpace went up against Sanford Wallace and Walter Rines, two notorious spammers. Wallace has the nicknames “Spamford” and “SpamKing” for his role as the head of a company that has sent as many as 30 million junk emails per day. Walter Rines is a local resident of Seacoast, New Hampshire, and both have been in hot water in the past due to their spam activities. Back in 2006, 2 years prior to their 2008 judgment, Wallace and Rines settled with the FTC on charges of distributing spyware. They agreed to stop doing it and pay a slap-on-the-wrist $50,000 fine.

Under the 2003 Federal CAN-SPAM law, each violation entitles the victim to $100 in damages, which can be tripled if the act was conducted “willfully and knowingly”. According to court records, Wallace and Rines worked together to create MySpace accounts and then emailed other MySpace members, asking them to watch a video in which they attempted to sell items.

MySpace told LA District Court Judge Audrey B Collins that some of the spam distributed by Wallace and Rines—much of it sent to teenagers—included links to third-party websites containing pornographic material. They then attempted to take over other accounts by stealing passwords.

This ruling is important because it sets a tone that spam will not be tolerated and reminds people that spam is, in fact, illegal. However, it’s not likely to stop the deluge of junk email in our inboxes every day.

Report Spam to [email protected]

Most people delete spam as an annoyance, but you can actually report spam to the Federal Trade Commission at http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/conline/edcams/spam/report.html, or you can forward it to [email protected].

What will this do? It will not stop the deluge of spam into your inbox, but it might give investigators more power to stop spammers as well as give them a better understanding of how prevalent the problem is and what the source is. A quick tip: Add [email protected] to your email address book to make it easier to forward spam.

In May of 2008, Yahoo! filed a lawsuit against an unknown group of individuals for allegedly sending out email messages to Internet users claiming they had won a lottery from Yahoo!. The suit targets individuals who sent out emails that read “Yahoo! Lottery!” in the subject line.

The fake lottery scam is a well-established hoax designed to trick unsuspecting email users into revealing valuable personal data such as passwords, credit card information, and social security numbers, but in this case the thieves made the mistake of using a well-known company to try and dupe customers, and Yahoo! took notice.

Why would Yahoo! file a lawsuit against unknown people? First of all, these spam messages were genuine-looking enough to fool a lot of people, and that does not bode well for Yahoo!. With over 260 million users, Yahoo! cannot afford to have their corporate reputation tarnished by people thinking the company has duped them. Secondly, Yahoo! is hoping that the actual identity of the spam scammers will be revealed in the court discovery process. We will be watching this case with great interest.

People like to think they are above falling for fraudulent schemes, particularly from emails that are misspelled and have offers that are simply too good to be true. However, the reality is that many people do buy into these scams because they want to believe they are true or they don’t have the capacity or knowledge to question such offers. When people do get duped, their anger and embarrassment often prevents them from reporting the crime.

One such scam is the “Nigerian letter” or “419” scam. Although there are many different names for this scam, it’s basically an “advance fee” scam, which we’ll explain shortly. The name is derived from the fact that the bulk of these scams have been traced back to Nigeria. The number “419” is a reference to the Nigerian penal code, which designates the crime of fraud as “Section 4-1-9”.

The “advanced fee” part comes from the fact that the sender, who often purports to be a Nigerian government official, sends the letter or email looking for someone willing to accept a large sum of money (often in the millions) but requires an advanced fee to ensure the transaction as a “show of honesty” on the victim’s part. The intended victim is reassured of the authenticity of the arrangement by forged or false documents bearing apparently official Nigerian government letterhead, seals, as well as false letters of credit, payment schedules, and bank drafts. The scam artist may even establish the credibility of his contacts, and thereby his influence, by arranging a meeting between the victim and “government officials” in real or fake government offices.

These Nigerian cases are extremely difficult to prosecute because they often are generated from overseas, and whenever you cross international boundaries, another layer is added to the investigation. More importantly, the cooperation of government officials in that country is required to prosecute and assist the criminals.

There have been several arrests recently in Nigerian scams. In June of 2008, Edna Fielder of Washington State was sentenced to 2 years in prison and 5 years of supervised release for her role in a Nigerian scam.

Fiedler was working with Nigerian accomplices and agreed to send fake checks to people in the U.S. The victims, duped into thinking this was an official transaction, agreed to cash the fake checks with the promise that they could keep part of the money for themselves as a “transaction” fee. Fiedler was the go-between for the Nigerians. She would receive the fake check packages, including phony Wal-Mart money orders, Bank of America checks, U.S. Postal checks, and American Express traveler’s checks, and then forward the packages onto the potential victims, keeping a piece of the cut for herself. In total, Fiedler has sent out around $600,000 in fake checks to victims. When the FBI searched her house, they found another $1.1 million in fake checks she was prepared to send out.

What we find most interesting about this particular case is that the U.S. Postal Service recently sent 15 investigators to Lagos and Nigeria to follow the trail of these letters. That means the Nigerian government had to sanction the actions of these inspectors, which is a dramatic change from just a few years ago. We’re not venturing a guess as to whether the officials were cooperative, but even allowing U.S. inspectors into their country to work the case is significant.

Recently, the FBI, working with the Spanish police, arrested 87 Nigerians suspected of the Nigerian 419 advanced fee scam. In this particular case, the suspects were accused of defrauding at least 1,500 people in a postal and Internet lottery scam. The Spanish police said millions of dollars were taken from the victims, most of them in the United States and European Union.

The twist on this case is that the victims were told they had won a substantial amount of money in a lottery and then were asked to send a payment before the prize money could be sent. Thousands of letters and emails, most in ungrammatical English, were sent out to prospective victims every day. The faked documents asked them to make an initial payment of $1,400 in “taxes or administrative costs”. The scam is estimated to have netted around $24 million.

It is estimated that only one in 1,000 recipients of the letters needed to fall for the fraud for it to make a profit. One in 1,000, yet over 1,500 people were willing to come forward and admit to being victimized. There’s no telling how many did not come forward. Among those duped in this particular scheme was an Anglican bishop.

In April of 2008, police in Newport Beach, California sent out a press release indicating that an 80-year-old resident had fallen victim to an “advanced fee” (419) scam in which he received an email claiming he had won an overseas lottery and was required to pay a processing fee to have the funds released. This is the typical scenario, but in this case, the victim was defrauded over the course of 2 years and duped out of $700,000. That amount may seem astronomical, but bear in mind that many of these types of scams are specifically targeted toward senior citizens, who might not be as aware of them.

These scams embarrass people, bilk them out of their money, and wreak havoc on their financial accounts. Recently, we were saddened to hear of the suicide of one of the victims. A young university student, who had recently emigrated from China to Britain, was taken in by one of these scammers to the tune of around $11,000. She hung herself when she discovered she had been defrauded.

Here are some facts about the Nigerian 419 scam:

• The U.S. Postal Inspection Service estimates that U.S. consumers have been duped to the tune of $120 million a year.

• IC3, the Internet Crimes Complaint Center, estimates the average loss for victims of Nigerian scams to be $1,922 per victim.

• The Financial Crimes Division of the Secret Service receives approximately 100 telephone calls from victims and potential victims and receives 300 to 500 pieces of related correspondence about this scam per day!

Here’s an example of a typical Nigerian advance fee letter, which can be received via email, fax, or post office mail. Note that there are many varieties of this type of letter in existence:

Lagos, Nigeria.

Attention: The President/CEO

Dear Sir,

Confidential Business Proposal

Having consulted with my colleagues and based on the information gathered from the Nigerian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, I have the privilege to request your assistance to transfer the sum of $47,500,000.00 (forty seven million, five hundred thousand United States dollars) into your accounts. The above sum resulted from an over-invoiced contract, executed, commissioned, and paid for about five years (5) ago by a foreign contractor. This action was however intentional and since then the fund has been in a suspense account at The Central Bank Of Nigeria Apex Bank.

We are now ready to transfer the fund overseas and that is where you come in. It is important to inform you that as civil servants, we are forbidden to operate a foreign account; that is why we require your assistance. The total sum will be shared as follows: 70% for us, 25% for you, and 5% for local and international expenses incidental to the transfer.

The transfer is risk free on both sides. I am an accountant with the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC). If you find this proposal acceptable, we shall require the following documents:

(a) your banker’s name, telephone, account, and fax numbers.

(b) your private telephone and fax numbers—for confidentiality and easy communication.

(c) your letter-headed paper stamped and signed.

Alternatively we will furnish you with the text of what to type into your letter-headed paper, along with a breakdown explaining, comprehensively what we require of you. The business will take us thirty (30) working days to accomplish.

Please reply urgently.

Best regards,

Howgul Abul Arhu

This scam is one of the reasons we advocate for centralized reporting of cyber crime. Here’s what the FBI website (http://www.fbi.gov/majcases/fraud/fraudschemes.htm) says about reporting Nigerian 419 letters:

If you receive a letter from Nigeria asking you to send personal or banking information, do not reply in any manner. Send the letter to the U.S. Secret Service, your local FBI office, or the U.S. Postal Inspection Service. You can also register a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission’s Consumer Sentinel (http://www.consumer.gov/sentinel/).

Historically, one telltale sign of a potential scam has been the poor spelling and grammar present in many spam and phishing attempts. Messages that read, “You to can be of great luck please,” and other awkward grammatical formations quickly belie their roots. To overcome this hurdle, malware authors are quietly recruiting people fluent in foreign languages on underground bulletin boards and list servers.

Have you ever swiped your credit card at a store or filled out a detailed form outlining your personal medical history, only to wonder where that information goes? Imagine if your most private information—your medical history, your financial profile, your adoption records, your credit card numbers—were compromised. Unfortunately, this happens to millions of people every year, many of whom become victims of credit card fraud, identity theft, and sometimes even blackmail.

Data breaches have largely been a result of a combination of poor security policies, out-of-date programs, and inattention. Here’s a list of just a few data breaches that have been reported:

• In March of 2008, Harvard University apologized for allowing their computer files to be hacked, resulting in the potential exposure of about 10,000 graduate students and student applicants.

• In March of 2008, a Broward County, Florida high school senior broke into his school district’s computer system and stole personal information about district employees.

• In June of 2008, Stanford University acknowledged that a laptop containing confidential personnel data of many Stanford employees was stolen. The laptop contained employee’s names, dates of birth, social security numbers, addresses, and phone numbers.

• In June of 2008, AT&T reported that a laptop containing unencrypted employee names, social security numbers, salaries, and bonus information was stolen out of an employee’s car.

• In June of 2008, Walter Reed Army Hospital confirmed that “sensitive information” on their patients was exposed in a breach.

• In April of 2008, Helping Homeless Veterans and Families of Indianapolis, Indiana reported that hundreds of files containing sensitive medical information, medical histories, and social security numbers were found in the trash on the east side of Indianapolis. The records were those of homeless veterans.

In June of 2008, Verizon Business Security Solutions released a “Data Breach Investigation Report” that made 500 forensic examinations of data breaches involving 230 million records. The conclusion of the study was that 87% (nearly nine out of ten) data breaches could have been prevented by “taking reasonable security measures”. Whereas 59% of “deliberate” breaches were the result of hacking and intrusions, some 90% of known security vulnerabilities that were exploited had patches available that would have taken care of the security holes at least 6 months prior. In other words, the bucket was leaking and the plug that would have shored up the hole was available for at least 6 months, but nothing was done to stop it up. That’s just a bad security policy.

Unfortunately, it’s very hard to regulate that the hospital, university, government agency, or store where you swipe your credit card keep their systems up to date with the latest patches. There are mandates for industries regarding compliance and there are certainly plenty of lawsuits after the data is breached (as well as fingers pointed in every direction), but all this does not protect the consumers whose information is stolen and whose lives are often turned upside down as they attempt to recover from their data being breached.

Verizon Business also concluded that although three-fourths of all data breaches led to compromised data within days, 63% of businesses didn’t know the data was breached for months afterward. Even more significant is that 70% of data breaches are uncovered by third parties, such as consumers. The most popular method of breaching data? Good old-fashioned hacking (59%).

Data Breach Laws

It may surprise you to learn that as of February, 2008, only 38 states had enacted data breach laws. California led the way over 5 years ago by enacting the landmark SB 1386 Data Breach Law. Other states have followed suit, but it still concerns us that 10 states still have no mandates requiring companies to notify customers when their data is compromised. These states are South Dakota, New Mexico, Iowa, Missouri, Kentucky, Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia. (Oklahoma has a breach law, but it only requires notification when a governmental agency experiences a data breach.)

The data breach laws have several components, including how much time an organization has to notify their customers of a breach, what the penalties are for failure to notify, whether or not customers can take private action against a company, and what kinds of exemptions might apply. For example, data that is encrypted is not likely to be discernable, so often it is exempt from data breach laws.

As of this writing, no federal data breach law is on the books. Several have been proposed, but none has been passed yet. Federal law would trump any state law, and as we understand it, although there is bipartisan consensus that a federal data breach law is needed, one of the sticking points is whether or not notification to consumers should be required. Another issue is that the state laws keep changing. For example, California just amended its laws to include mandatory notification of patients when their health information is breached. Other state changes have addressed the length of time credit card information can be stored.

In June of 2008, Carnegie Mellon University released an interesting study based on U.S. Federal Trade Commission data that stated that the data breach disclosure laws—the same laws put in place that require organizations to reveal when personal information has been compromised—have been ineffective in reducing identity theft.

The problem with this study is that it addresses the wrong issue. The data breach laws were not put into place as a means of deterring identity theft. The laws were meant to minimize the damage once the theft occurred. Victims of identity theft are often unaware their identities have been stolen—sometimes for years. As in the Hannaford Brothers and TJ Maxx data breaches, as soon as customers were advised of the breach, they could be on guard to prevent any further fraud. That is where the data breach laws do their work. They were not meant to stop the crime, but to make sure the damage is as minimal as possible.

The Privacy Rights Clearinghouse (www.privacyrights.org) is a nonprofit consumer information and privacy advocacy website. One of the most interesting features of this site is its chronological listing of all reported data breaches. The numbers and volume are staggering, and it is constantly updated with the latest news about stolen data. Just click “A Chronology of Data Breaches” under the Consumer tab to read about the most recent breaches.

According to the FBI’s “2006 Internet Crime Report,” over 200,000 complaints of cyber crime were filed in 2006 (the highest yet), with a total loss of $198.4 million. The number-one cyber crime complaint was auction fraud, which accounted for nearly 45% of all complaints. Product misrepresentation was the primary reason stated, followed by nondelivery of an item. About 70% of the fraud victims were scammed through online auctions, and about 30% of the victims were scammed via email. The average median loss per auction fraud complaint was $602.50.

Auction fraud is particularly upsetting because it relies on trust. No one wants to think they’ve been duped.

Before you bid on that French Louis XV commode for $35,000 (yes, we saw one at the time of this writing), you might want to consider using an escrow service. An escrow service holds your payment to the seller until the item is authenticated. Obviously the seller has to agree to this, but it would seem fair to say that any legitimate seller dealing in high-end items such as antiques would be willing to participate in this process. Think of it like a “contingency clause” pending house inspection.

Oddly enough, there have been numerous cases of fraudulent escrow services that took the buyer’s money and never released it to the seller. As a result, eBay is very clear that the only escrow service they will endorse is Escrow.com (www.escrow.com).

Although some people are afraid to use their credit card for online transactions, we actually encourage it because most credit cards companies will work with you to get your money back in case you are a victim of fraud. A credit card also limits your liability for how much you are personally responsible for if you do not receive an item. Do not use your debit card because your personal bank account could get wiped out.

eBay and other auction sites almost always have a rating system. Heed it. Look at the rating and read the negative ones first. What percentage of feedback is positive? Even if there have been a few legitimate problems, such as a delay in shipping and goods arriving damaged, most sellers will still have a good rating. If they do not, this is a red flag that something could be wrong.

How long has the seller been online? If a seller has a brand-new account and is offering a deal that seems too good to be true, it probably is.

Is the seller located in the United States? If not, it could be more difficult to resolve any issues that arise.

Google the seller’s online name. If the seller does a lot of business, you might find him or her mentioned elsewhere. Be informed.

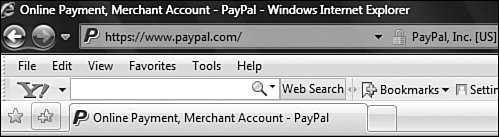

Figures 11.5 and 11.6 show a secure transaction. Instead of “http,” the URL or address reads “https” to designate a “secure” site that is encrypted. The padlock on the bottom also indicates a secure site. Whenever you are at a site that requires any kind of credit card or financial account information, make sure you see “https” and a padlock icon. If you don’t, you could be at a fraudulent website!

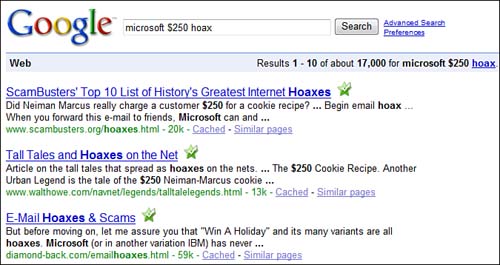

We’ve all received one—the email in your inbox that reads, “I don’t usually forward these things, but my friend, who is a real attorney, sent me this”. It goes on to say that Microsoft founder Bill Gates is “sharing his good fortune” and “if you forward the email, Microsoft will pay you $245”. Not really. This is one of a thousand different hoaxes that fill our inboxes and prey on our vulnerabilities. Some of these hoaxes have been circling the Internet for years, because it only takes one person to believe them and pass them along.

Trust your gut instinct. If it sounds too good to be true, it is. Remember that. Better yet, take the keywords in the email, add the word “hoax,” and Google the entire phrase, as shown in Figure 11.7.

Many people who apply for work-at-home positions are struggling to balance family care with trying to make ends meet. Some people who apply for positions are disabled. We find these types of scams, which prey on people who need the extra money the most, particularly reprehensible.

Staffcentrix, a work-at-home advocacy organization, did a study in 2006 that revealed that only one of every 42 work-at-home offers was legitimate (source: www.staffcentrix.com).

Here’s a list of some of the “typical” offers made by work-at-home scammers:

• “Work part time in your own home and make $500 to $1,500 your first month! It couldn’t be any easier!”

• “A genuine opportunity! Guaranteed income!”

• “Work minutes a day at home and earn enough to make your dreams come true”.

Remember that con artists pitching work-at-home schemes rake in $427 billion dollars a year. These scams are a favorite way for con artists to exploit people.

First, and most important, legitimate jobs that allow “telecommuting” rarely post their positions with a title of “Work at Home”. That, in and of itself, is a good tipoff that the job may not be legitimate. “Medical transcriptionist” is a legitimate job title. “Work at Home—Easy Typing” is not.

Second, be wary if the offer is too good to be true. We don’t mean to burst anyone’s dreams, but an offer of “$1,500 a week for just 15 hours a week” should make you think twice.

Third, if the offer arrives in your inbox and you didn’t ask for it, consider it spam. Delete it.

And finally, if the job offer does not have a legitimate job description and is deliberately vague, consider it a hoax.

Think about what a legitimate company would offer and expect nothing less. If a real company is behind the offer, they should have a legitimate company website, Human Resources department, phone numbers that can be authenticated, and so on. Remember that lots of money can be made from work-at-home scams, and sometimes they can be fronts for other scams that could land you in a world of trouble, so proceed cautiously whenever you consider any of these offers.

For every 42 offers, only one is legitimate. Keep that number in mind and act accordingly. We want to emphasize that there are some legitimate work-at-home offers, but you really need to do your research before you commit to one of these offers.

Earn $500 a week as a mystery shopper? Not likely. The only mystery about this scam is how they can keep coming up with more and more clever ways to bilk hard-working people out of their money.

Secret shopper or “mystery shopper” scams pretty much work the same way as other shop-at-home scams. A potential victim responds to an ad and receives information back from what appears to be a legitimate company. Often, this company even has a telephone number to call to verify its credentials. They may even send out an “employment packet” with training materials, training schedule, and so on. There’s nothing like the human touch to bilk someone out of thousands of dollars.

Once the victim is convinced the company is legitimate and she can make money simply by shopping—something she may already love to do—the company sends her their first package with instructions and a check, usually a cashier’s check, for several thousand dollars with the orders to cash the check right away. There’s usually a stipulation that the check-cashing task must be completed “within 48 hours” or she will be fired. The cashier’s check is really counterfeit, but it clears the bank because of the delay in notification that it is actually a counterfeit.

The victim is told that her “secret mission” is to test the effectiveness of a money-wiring service. Sometimes it’s Western Union. We’ve heard of several that work with MoneyGram, which is a money-wiring service in Wal-Mart stores. The victim is instructed to test the effectiveness of the money-wiring service or is actually given shopping tasks at local chain stores and then asked to wire the remaining money—which can be several thousand dollars—back to the company. The victim is told to carefully document and evaluate the entire process to give it authenticity. It takes only a matter of time before the victim is notified by her bank that the check she cashed was a fake and she is now responsible for making up that amount.

No legitimate company would ever ask someone to wire money to someone they didn’t know. Know that it can take up to a week or more to determine whether a check is good, especially if the check, even a cashier’s check (which is supposed to be more “legitimate”), is from a foreign country. If you are asked to front any money, told you must pay fees, or have any suspicions, don’t follow through with the task. There are legitimate mystery shopper programs, but read up about them first. Google the company name and see if anyone has written anything about them—good or bad. In other words, use common sense!

These types of scams, many of which masquerade as work-at-home jobs, rely on people to become “money mules”. Basically, victims are being asked to launder cyber crime money. Many of these scam artists comb employment sites such as Monster.com and Careerbuilder.com to find resumes of people seeking employment. The offer is often to make a few hundred dollars a week, and it almost always involves money transfer transactions either online via PayPal or directly in person. These scams almost always involve a payment with money being wired somewhere, but the results are almost always the same—the victim finds out that the transaction was fraudulent and is left holding the bag for the amount of the damage—which can often run in the thousands of dollars. In addition, the victim has often handed over his own personal account information to the scammers in the process of completing the transaction. Be smart and do your homework.

Whenever we are approached about a possible hoax, we turn to Google and run a search using the company’s name and the word hoax or scam as the keywords. If we’re lucky and the offer is indeed a scam, someone may very well have posted about it somewhere on the Internet. Use the power of the Internet to try and debunk these scammers! They can hide behind fake websites and legitimate-looking documents, but they can’t hide behind powerful search engines that reveal what they really are. Just be aware that many of these scam artists are incredibly good at mimicking legitimate companies, even building fake “virtual” store fronts by copying the websites of legitimate businesses and posting them.

One of the most interesting facets of cyber crime is the technique of social engineering, which means the cyber crime is perpetrated by playing on the vulnerabilities of people.

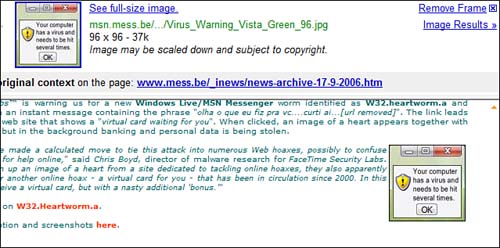

Social engineering can involve a big red box that suddenly pops up on your computer monitor announcing “Security Alert—Click here”. It might be an email that appears to come from your bank and states, “Critical Warning—Your Account Has Been Compromised. Click here to log in”. See Figure 11.8 for an example.

Ever had a warning pop up indicating your computer was infected? The thieves that develop these programs are very good at preying on our vulnerabilities, fears, and trust. For someone who is not computer savvy, these pop-ups appear to be legitimate warnings. They are designed to scare you into clicking them so more malware can be installed on your computer. Once installed, the malware could be used to log your keystrokes, send your personal data to another computer, or hijack your computer for use in perpetuating spam or phishing scams, or worse. The rule of thumb is to install a solid virus-protection program (see Chapter 16 for information on antivirus programs) and respond only when that program say there’s a problem.

400 People Click to Get a Computer Virus

In an interesting experiment on social engineering, an IT security professional, Didier Stevens, placed the Google ad you see in Figure 11.9 on a website he purchased called www.drive-by-download.com. The ad offered to infect the user’s computer by simply clicking it. Stevens ran the ad for 6 months. The results? Four hundred and nine people clicked the ad. Of course, Stevens did not actually infect anyone’s computer, but it points to the fact that even with the best protections in place, software companies cannot control what people will do.

We couldn’t resist citing some recent statistics just released in April of 2008 by the FBI based on data from the Internet Crime Complaint Center (www.ic3.gov). The statistics showed that “men lost more than women on average to Internet scams—$765 for men versus $552 for women”.

And to be fair, we’ll also cite another study conducted in the UK that asked 576 office workers in London to fill out a survey in return for a chocolate bar. The survey asked for a lot of personal information, including name, address, birthdate, and computer passwords. Only 10% percent of men gave up their passwords, whereas 45% of women gave up theirs (source: InfoSecurity Europe). It’s chocolate, for heaven’s sake!

We can’t say it enough—use common sense! Check everything out. Google all potential offers. You should always assume that email, job offer, or the promise of “riches beyond your wildest dreams” is not legitimate. On that note, we need to say that there are many legitimate mail order, direct marketing, and work-at-home businesses. Do your research and trust that inner voice that says, “This is too good to be true”. It’s usually right!