A Data Modeling Story

It was another dreary, rainy day, and the bad news seemed to be coming in waves.

Yet another IT project had been cancelled. Now we were having the project postmortem to assign blame and begin the process of punishing the guilty. My boss was visibly sweating as he tried to defend our data model and database design. His peers were jointly attacking like hyenas swarming on a weakened gazelle.

Just as the walls of his last defense were beginning to be breached, I felt a buzzing in my pocket from a poorly timed cell phone call. I checked the caller Id to find it was my mom. She only calls during work hours when it is critically important, so I slipped out of the conference room to take the call in the hallway.

It was an emergency room doctor calling to tell me my mom was having severe chest pains and was undergoing a series of tests. I said I would be right there and returned to the conference room to excuse myself. As I opened the door, the corporate Vice President started asking me leading questions. As the focus of questioning migrated back to my boss, I was thinking about all the love and effort my mom invested in my upbringing. Suddenly, my life looked like an emergency room triage process where priorities are set and action is taken, immediately. I abruptly interrupted the Vice President, announced my mother’s condition, and then exited while the Vice President was trying to ask me “just one last question.”

As I arrived at the hospital, nurses were adding some pain medication to her IV solution. The tension in her face visibly relaxed as the drugs began to work. The doctor arrived just moments later to tell us that she had not had a heart attack. Her face relaxed another level, returning to her normal demeanor. While we were waiting to check out of the hospital, she asked me to turn on the TV. A documentary was on PBS about the Dust Bowl. Mom had lived through the Dust Bowl as a child in Kansas. When she sees things from the past, they trigger memories and storytelling. She told me this story:

Brian, when our ancestors first came to the plains of Kansas, the grass was eight feet tall. In order to see across the Great Plains, you had to sit on a large horse, and even then, the grass was still shoulder high. Our family had 250 acres of prime land acquired under the Homestead Act, but we could farm only a small section of it due to the prairie grass. When the tractor was invented, we bought one and started to plow up the entire acreage. In the first two years, we paid off all our debts and were positioned to be millionaires in about four more years.

The neighboring Native Americans would stop us on the road and warn us that if we kept plowing under the native grass, the Spirit of the Earth would become unbalanced. They said we would come to regret the tractor that seemed like such a good thing to us at the time.

Our family was mostly of German and Irish descent, and our cultural traditions did not recognize the Spirit of the Earth as an entity of significance. Grandpa Kappelman got the family together to discuss this environmental issue relative to the financial bonanza that our new tractors were uncovering. Of course the vote was a landslide for riches, with only a single vote cast for preservation of the environment. Aunt Ida, the lone dissenter, talked to animals and trees, and she insisted her talking was a dialog. Her lone irrational vote was considered typical for naive Ida.

The Kiowa tribe had warned the technologically advanced white tribe, but the warnings were almost universally ignored. All our neighbors got tractors, and for the next harvest season the riches flowed like a flooding Texas river in springtime.

That October, the Kiowa tribe was exiled to a reservation in Texas with no grass, no trees, and no wildlife. There was a brief article on page nine of the local paper, and people discussed the issue for a couple of days. We felt safer now that they were gone. We were also certain that we were superior to the primitive tribes who did not understand our technology and our advanced civilizations.

The true wisdom of the Kiowa began to germinate in our minds when, in the next year, there was no rain and the wind blew day and night for weeks at a time. We got no rain for six years, and of course the crops all died, as did the children of Kansas by the thousands. Breathing in dust becomes impossible to avoid when a cloud of it blows across the barren plains, 20,000 feet tall moving at 50 miles an hour. Children seemed to be particularly susceptible to death from dust pneumonia. So the Kiowa nation, who had the wisdom to understand the environment, was banished to obscurity. And we, the advanced civilization, stood starving and dying by the thousands.

Our family, with one exception, believed that our farming and plowing actions did not cause the Dust Bowl. They asserted that it was just a quirk of nature, soon to pass. Further, we believed—minus one vote—that the Spirit of the Earth was not out of balance, and we thought the rains and big profits would return any day now.

Well, after a decade of drought, the rains returned and a new crop was sprouting into a certain bumper crop. Ida was surprised that the Spirit of the Earth was back in balance so quickly. Half way through the growing season, a cloud of grasshoppers swarmed through the farm and ate every living plant in sight over the course of a week. The grasshoppers blocked out the sun to the point where you needed to turn on a light to read in the house at noon on a clear day. With Biblical catastrophes popping up repeatedly, the Kiowa leader returned to town and repeated his warning about the glossy shine of wealth and the subtle and hidden virtues of harmony with nature.

Grandpa Kappelman reconvened the family elders for a vote on moving to California. Ida insisted that we start with a vote on the issue of the Spirit of the Earth being out of balance. The German pride in the room blocked this vote, but the undercurrent of contrition was palpable a mile away. The vote was to stay in Kansas and accept responsibility for our role in inflicting environmental damage. The Federal farming practices to preserve the soil were adopted completely. In time, the Spirit of the Earth would be healed enough to support farming.

So the lesson here is that the web of environmental dependencies is easy to ignore, while the lure of wealth and power is hard to ignore.

This seemed to be my day to learn about setting priorities for broad, long-term objectives. We checked out of the hospital looking forward to returning home. When we got home, my son Luke was playing a computer game. He did not look up to greet us. Rather, he waved briefly and then returned to the slaughter. I am having difficulties understanding Luke and his enigmatic generation.

Luke is 9 years old, and I, his 62-year-old father, cannot keep up with all the games, gadgets, movies, and lingo. In some aspects, I see Luke’s generation surpassing mine, while in other ways I see the opposite to be true. My generation was shaped by non-electronic games and gadgets, where the electronic aspects of games and gadgets were generated by our neurons, no batteries required. We were required to use our imaginations in our play, and we were encouraged to construct our own gadgets.

Luke gets his games and gadgets in packages that say “batteries required.” He just follows the pathways available in the package. Granted, the graphics are great and the excitement is high, but there is still a loss of creativity. My generation was raised and shaped by a community of positive and constructive (non-zero sum) social bonds. These bonds came from social groups such as family, church, neighborhood, scouting, sports, band—institutions that model community.

Growing and learning from face-to-face social interactions in a positive social environment builds critical interpersonal strengths such as listening, humility, team behavior, compromise, and leadership. Luke’s social interactions are increasingly migrating from face to face and becoming gadget to gadget. The contents, integrity, and veracity of his social bonds decline as he migrates to non-face-to-face electronic social interactions. Too many action-oriented video games targeted at males portray our world today as being mostly a zero-sum affair in which, for every winner, there’s a loser. The reality is that we should be teaching young males to seek non-zero sum relationships; when presented with an adversary. Luke’s gadgets promote the opposite.

While recognizing that Luke’s generation outstrips mine in a dozen ways, I finally put my foot down and demanded that he spend some time operating back in my old-fashioned times. Luke will now earn his toy money with a job. Yes, that word actually was “J-O-B.” That word means you are working and getting paid by the customer—not by dad.

We have 17 acres containing several groves of lemon trees. My brother has been harvesting them for 47 years; he recently moved to a retirement home. Now Luke is getting to be the boss of his new lemon business. Luke will get to express his creativity in the lemon business (or get no toys), and he will do so with customers and partners who require constructive social interactions for all parties to be satisfied in the arrangement.

Luke was fairly stunned to realize that “good old dad” was actually going to stop buying toys and make his summer job the single source of money for his acquisition of new things. When the implications of this sudden and sweeping change were fully grasped, Luke asked me, “How do I run a lemon business?” I told him that he—himself, by himself—would have to answer this question for the first season. After that, I would assist him more and more each season by giving him business tips and a computing system to manage his business. For the first season, the only advice I would be giving Luke were the paradigms called value chain and data modeling. Value chain is the collection of processes that a business uses to convert raw materials into finished goods. Data modeling is the specification of the things of interest to a business.

I knew that this vision of how businesses (and the entire world) operate would fall on deaf ears, but planting this foundational seed in the back of his mind would bear fruit in his teen years, just as he was teetering between self-indulgent lethargy and self-sacrificing hard work. Luke’s business experiences would someday keep the teenage Luke on the path of progress. And sure enough, Luke half listened to and half responded to my lecture. Over the coming lemon seasons, my prediction of the benefits of these paradigms became increasingly true as his mental investment in “value chain” and “data modeling” rapidly became the key paradigms driving his business model evolution.

I chose to give Luke his introduction to value chain during a winter snow storm after the electricity went out. We were hovering near the fireplace when I said, “Lukas,” his formal name, which engendered fear and rapt attention, “it is time for your first business lesson. Put your cell phone game down and listen, please.” He pleaded again for clemency and a reprieve from his financial circumstance, but I denied his appeal and proceeded with his opening business lesson. “Luke, do you remember that year when dad took medical leave from work for a few months?” He, of course, easily recalled it, since it was the first time he fully bonded with his newly adopted dad.

I had had a stroke and cancer and spent months on leave with Luke, who was three at the time. We would get up early in the morning and walk the trails of our 17 acres to observe and revel in nature’s displays. Playing with a three-year-old boy surrounded by nature was a far cry from my adult urban corporate environment, where I suspect that my health condition had germinated. I had my triage priorities set on corporate success, and I forgot about the joy of a child playing in the forest. The good part about a stroke and cancer is that you get your triage meter adjusted big time. Taking the time to play with your three-year-old son in the forest all day, while feeling eternity’s hand on your shoulder, was both healing and scary.

Early one fall morning, we were walking the trails in deep fog when the sun suddenly poked her fingers of light out between the lifting veils of fog. As we rounded a corner in the trail, there were a dozen spider webs on one large tree, with fog-dew-drops on every strand. Each intersection of strands contained a glistening crystal. The light was hitting the drops in a way that made them seem to be self-luminous. This light show ebbed and flowed with the patterns of lifting fog. As we watched, a fly crashed into one web and struggled to escape. With each struggle, the web flexed and the light from the dew drops danced in tune with the undulating fly. Then, the branch holding the upper part of the web started to shake from the struggle below. This branch, in turn, shook its neighbor’s branch which, in turn, shook the web of the neighboring spider. Now both webs were dancing out of phase to the same struggle, and instantly the light show doubled in size and intensity. The neighboring spider ran out from his watch station and looked for the source of the ruckus. After a complete scan of his web, he—undoubtedly dejectedly—returned empty handed.

After reminiscing about that morning, I told Luke that value chains and spider webs are similar things. The spider web tells the spider about all of the action within his sphere of control. In a similar way, you will have a sphere of control in your summer lemon business. This sphere of control will be defined and managed by your value chain and your data model. These two ideas will be the keys to how you manage, evolve, and profit from your business. Additionally, you will need to interact with the value chains of your partners and customers. Your web will touch your neighbor’s webs. This interaction should produce a win-win relationship across all parties or else your business will fail. These win/win, or non-zero sum, relationships are critical to your lemon business’s success. There will be times when you are having problems with employees, customers, and partners in your business. You will either find a win/win solution or your business will suffer. Finding a win/win solution is more likely when value chain and data models are the paradigms that shape your thinking. Also, when you use the paradigms of value chain and data modeling to design your business, guide the execution of your business, and measure your business, you will be more likely to increase your profits. Upon hearing “increase your profits,” the gaze of glaze finally fully evaporated from Luke’s face and a look of rapt attention with ears wide open suddenly appeared.

So an analogy would be if my web is my value chain, and if your web is your value chain, and if the tree branches are the agents that tie our value chains together, then there is a higher value chain that is the union of our value chains.

Another analogy using the dust bowl example is if the Earth’s environmental ecosphere is a value chain, and if the world’s economy is a value chain, and if the environment impacts the economy, and if the economy impacts the environment, then there is a higher value chain that is the union of the two value chains.

Ultimately, the union of all interdependent value chains is the real world that we experience every day. This invisible set of cause-and-effect links must be clearly understood to be successful in business, environmental science, economics, and just about any endeavor. Information systems (such as brains and computers) view subsets of the real world value chains, since information systems are limited in their capacity and resources.

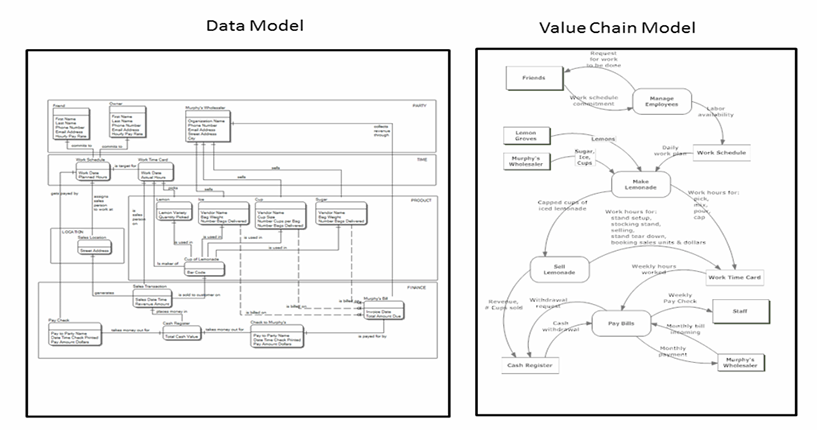

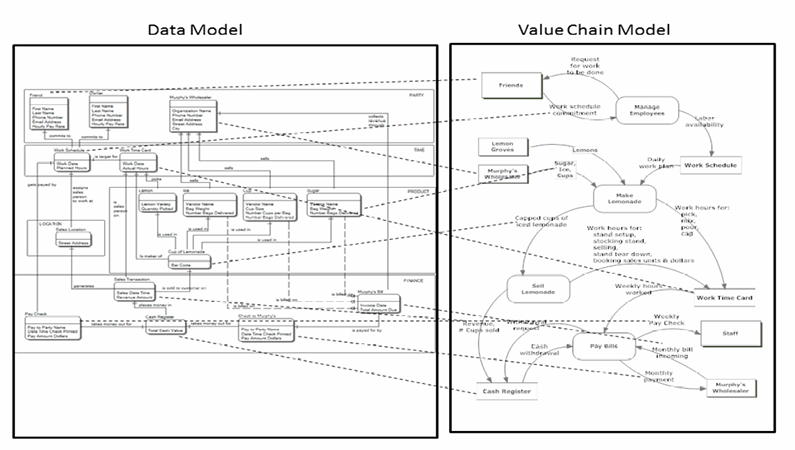

The models below from Luke’s lemonade business have some separate things (boxes) and have some interdependent things (lines between boxes). These models are purposely small so that the principle of separate things being interwoven can be seen. These diagrams are presented later in a more readable form as they are built through the chapters that follow.

To further demonstrate interdependence in this simple lemonade business, I will add some dependencies between the data model and the value chain model, shown on the next page with the dashed lines.

Businesses and computer systems consist of things all woven together into a web by a particular configuration of relationships.

Hopefully the things and relationships in our models match the real world things and relationships of our business. Also, we hope that the things and relationships of our models are faithfully built into our information systems. If so, the business will get maximum value from their investment in computing capability.

Key Points

- We tend to see the differences between things; only secondarily do we consider the interdependencies between things.

- We tend to overlook the degree to which things are highly interdependent.

- Value chain and data models clearly depict how our “separate things” are actually completely “interdependent things.”