Mastering Autofocus Options | 4 |

The autofocus system found in the Sony a7 IV is one of its most innovative features. The camera has the ability to lock in on subjects, including people and animals (birds, dogs, and cats—using face/eye detection), and track motion. Compared to the a7 IV’s predecessor model, this camera can seamlessly switch between eye, face, and body tracking, and use these modes when shooting video, as well. And if your subject isn’t a person or suitable animal, the camera can deploy pattern detection and use both subject color and brightness to find and lock focus.

The a7 IV is even able to focus in dimmer environments than before: down to –4 EV with a lens having an f/2 maximum aperture. For those who can’t calculate EV in their head, that’s equivalent to an ISO 100 exposure of 60 seconds at f/2. This camera can now automatically focus in what you might consider to be available darkness.

As capable as the a7 IV’s AF system may seem, there is still one logistical problem to overcome: the camera doesn’t really know, for certain, what subject you want to be in sharp focus. It may select an object and lock in focus with lightning speed. However, the focus plane isn’t guaranteed to be your intended center of interest in your photograph. Or, the camera may lock focus too soon, or too late. This chapter will help you understand the options available with your Sony a7 IV so you can help the camera understand what you want to focus on, when, and maybe even why.

Getting into Focus

Simply put, focus is the process of adjusting the camera so that parts of our subject that we want to be sharp and clear are, in fact, sharp and clear. We allow the camera to focus for us, automatically, or we can rotate the lens’s focus ring manually to achieve the desired focus. Manual focusing is especially problematic because our eyes and brains have poor memory for correct focus. That’s why your eye doctor conducting a refraction test must shift back and forth between pairs of lenses and ask, “Does that look sharper—or was it sharper before?” in determining your correct prescription. Too often, the slight differences are such that the lens pairs must be swapped multiple times.

Similarly, manual focusing involves jogging the focus ring back and forth as you go from almost in focus, to sharp focus, to almost focused again. The little clockwise and counterclockwise arcs decrease in size until you’ve zeroed in on the point of correct focus. What you’re looking for is the image with the most contrast between the edges of elements in the image.

The a7 IV’s autofocus mechanism, like all such systems found in modern cameras, also evaluates these increases and decreases in sharpness, but it is able to remember the progression perfectly, so that autofocus can lock in much more quickly and, with an image that has sufficient contrast, more precisely. Unfortunately, while the camera’s focus system finds it easy to measure degrees of apparent focus at each of the focus points in the viewfinder, it doesn’t really know with any certainty which object should be in sharpest focus. Is it the closest object? The subject in the center? Something lurking behind the closest subject? A person standing over at the side of the picture? Using autofocus effectively involves telling the a7 IV exactly what it should be focusing on.

Learning to use the a7 IV’s modern autofocus system is easy, but you do need to fully understand how the system works to get the most benefit from it. Once you’re comfortable with autofocus, you’ll know when it’s appropriate to use the manual focus option, too.

As the camera collects focus information from the sensors, it then evaluates it to determine whether the desired sharp focus has been achieved. The calculations may include whether the subject is moving, and whether the camera needs to “predict” where the subject will be when the shutter release button is fully depressed and the picture is taken.

The a7 IV has a hybrid autofocus system, using two technologies called contrast detection autofocus (CDAF) and phase detection autofocus (PDAF). I’m going to provide a quick overview of contrast detection first, and then devote much of the rest of this chapter to optimizing your camera’s use of its phase detection features.

Contrast Detection

This is a slower, but potentially more accurate mode, best suited for static subjects, and was originally the only kind of autofocus available for mirrorless cameras and for dSLRs when shooting in their live view and movie modes. The innovation of adding phase detection abilities to the sensor itself (as I’ll describe shortly) made contrast detection a fine-tuning option for hybrid autofocus systems that combined CDAF and PDAF.

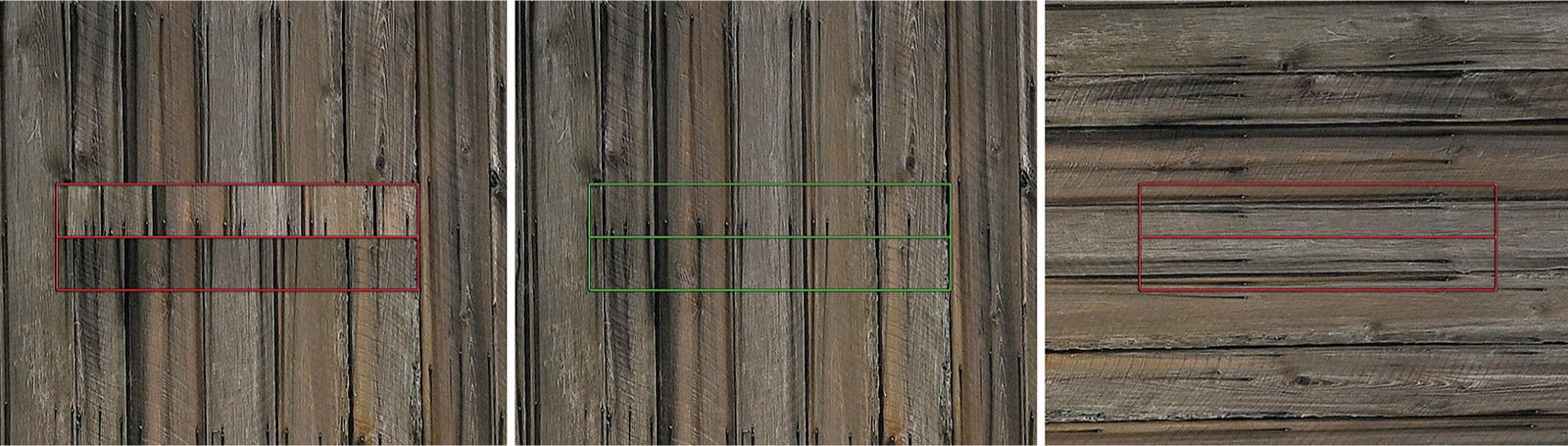

Contrast detection is very easy to understand, and is illustrated by Figure 4.1, a close-up of the side of an old barn. At top in the figure, the transitions between the edges found in the siding and foundation image are soft and blurred because of the low contrast between them. Whether the edges are horizontal, vertical (like the siding), or diagonal doesn’t matter in the least; the focus system looks only for contrast between edges, and those edges can run in any direction at all.

Figure 4.1 Focus in contrast detection mode evaluates the increase in contrast in the edges of subjects, starting with a blurry image (top) and producing a sharp, contrasty image (bottom).

At the bottom of Figure 4.1, the image has been brought into sharp focus, and the edges have much more contrast; the transitions are sharp and clear. Although this example is a bit exaggerated so you can see the results on the printed page, it’s easy to understand that when maximum contrast in a subject is achieved, it can be deemed to be in sharp focus. Although achieving focus with contrast detection is generally quite a bit slower, it can be used to fine-tune focus on a subject that has already been brought into general focus using phase detection (described next). There are several advantages—and disadvantages—to contrast detection, and I’ll summarize them shortly.

Phase Detection

Phase detection is easily much more rapid than contrast detection. The challenge is to make its operation as accurate as possible. Digital SLRs have always used PDAF, with an array of tiny autofocus sensors, located in the “floor” of the mirror box, and a small portion of the illumination directed downward to the autofocus sensor array. In the a7 IV, phase detection is built into pixels embedded in the sensor and combines with contrast detection to give us, potentially, the best of both worlds. I’ll show you the location of the PDAF and CDAF areas shortly.

Phase detection is also used in a different way when you use A-mount (rather than E-mount) lenses attached to the optional LA-EA2 or LA-EA4 A-mount lens adapters. Both adapters have their own built-in phase detection autofocus systems that bypass and replace the hybrid AF phase/contrast detection technology built into your camera.

The phase detection pixels in the a7 IV’s sensor split incoming photons arriving from opposite sides of the lens into two parts, forming a pair of images, exactly like the rangefinders used for surveying and in rangefinder-focusing cameras like the venerable Leica M series. The dual images are separated when out of focus, and then gradually brought together to achieve sharp focus, as shown from top to bottom in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 In phase detection, parts of an image are split in two and compared (top). When the image is in focus, the two halves of the image align, as with a rangefinder (bottom).

This process tells the camera when the image pair are “in phase” and aligned. The rangefinder approach of phase detection tells the a7 IV exactly how out of focus the image is, and in which direction (focus is too near, or too far) thanks to the amount and direction of the displacement of the split image. The camera can quickly and precisely snap the image into sharp focus and match the lines. If necessary, the a7 IV’s contrast detect feature can follow up to perfect the plane of focus.

The PDAF sensors in the a7 IV are all line sensors, which means they work best with features that transect the sensor either perpendicularly or at an angle, as visualized in Figure 4.3, left. It’s easy to detect when the two halves of the vertical lines of the weathered wood are aligned. (See Figure 4.3, center.) However, when the same sensor is asked to measure focus for, say, horizontal lines that don’t split up quite so conveniently, or, in the worst case, subjects such as the sky (which may have neither vertical nor horizontal lines), focus can slow down drastically. One such scenario is pictured in Figure 4.3, right. Fortunately, as I mentioned earlier, the a7 IV’s contrast detection AF will come to the rescue and take over where phase detection AF is stymied.

Figure 4.3 When an image is out of focus, the split lines don’t align precisely (left). Using phase detection, the a7 IV is able to align the features of the image and achieve sharp focus quickly (center). Horizontal lines aren’t ideal for horizontally oriented sensors and require vertical contrast detection to achieve final focus (right).

As with any rangefinder-like function, phase detection accuracy is better when the “base length” between the two images is larger. (Think back to your high school trigonometry; you could calculate a distance more accurately when the separation between the two points where the angles were measured was greater.) For that reason, phase detection autofocus is more accurate with larger (wider) lens openings—especially those with maximum f/stops of f/2.8 or better—than with smaller lens openings, and may not work at all when the f/stop is smaller than f/8. As I noted, the a7 IV is able to perform these comparisons very quickly.

Comparing the Two Hybrid Components

The Sony a7 IV autofocus system uses both phase detection autofocus (PDAF) and contrast detection autofocus (CDAF) to provide a combination of fast and accurate AF, together covering virtually all of the frame. Figure 4.4 shows the layout of the autofocus points and zones used. The figure shows the PDAF and CDAF areas overlaid on each other, but I’m illustrating them separately for easy reference. In real life, they work together in tandem.

- ■Phase detection points. The phase detect areas of the a7 IV, represented by the green rectangles at top in Figure 4.4, are spread over a wide area. The zone covered by contrast detection is shown as a dark blue rectangle.

- ■Contrast detection zones. The blue boxes at bottom in Figure 4.4 represent the 425 areas of the sensor used by the a7 IV when deploying contrast detection in full-frame mode. The surrounding area covered by the phase detection points is represented by the green rectangle.

- ■Crop mode coverage. One often-overlooked advantage of using the a7 IV APS-C/Super 35 crop mode is that both the CDAF and PDAF areas cover the entire frame, because the outside area of the sensor is cropped out. (See Figure 4.5.)

- This effective extended coverage can be useful for sports photographers, who may have subjects in all parts of the image. In general, however, crop mode may not be your best option for fast-moving subjects, especially birds-in-flight, because the a7 IV fills the display with the cropped image, and you lose the ability to “preview” where your subject is before it enters the APS-C “frame.”

Figure 4.4 Autofocus zones for phase detection (green boxes), top. Contrast detection areas (blue shaded area), bottom.

Figure 4.5 In APS-C/Super 35 mode, the entire cropped frame is filled with PDAF and CDAF areas.

The hybrid autofocus system uses both types of AF. The process begins by rapidly focusing using PDAF, because the rangefinder approach always tells the camera whether to move focus closer or farther, and by approximately how much. No hunting is required, which is often the case with contrast detection, which needs to tweak the focus point until it settles on the sharpest position.

Once the PDAF has done its stuff, contrast detection kicks in, using its finicky but more accurate focusing capabilities to fine-tune focus. So, you end up with speedy initial focus (PDAF) and slightly slower final adjustments (CDAF), providing a perfect hybrid compromise. That’s why Sony didn’t switch to phase detection completely. Here’s a quick rundown of the advantages of a hybrid system:

- ■Contrast detection works with more image types. Contrast detection doesn’t require subject matter to have lines that are at angles to the PDAF points to work optimally, as phase detection does. Any subject that has edges running in any direction can be used to achieve sharp focus.

- ■Contrast detection can focus on larger areas of the scene. Whereas phase detection focus can be achieved only at the points that fall on one of the special autofocus sensor pixels, with contrast detection much larger portions of the image can be used as focus zones. Focus is achieved with the actual sensor image, so focus point selection is simply a matter of choosing which part of the sensor image to use.

- ■Contrast detection can be more accurate with some types of scenes. Phase detection can fall prey to the vagaries of uncooperative subject matter: if suitable lines aren’t available, the system may achieve less than optimal focus. In addition, accuracy decreases as the maximum aperture baseline used for calculations becomes smaller. A lens with a maximum aperture of f/5.6 will focus with less accuracy than one with an f/1.8 maximum aperture. Contrast detection focus is more clear-cut. In most cases, the camera is able to determine clearly when sharp focus has been achieved.

- ■Phase detection “knows” which direction to focus. The split image seen by phase detection sensors reveal instantly whether focus is too close or too far. There is no need to “hunt” for the focus point, as the AF system can immediately adjust in the proper direction. That boosts focus speed considerably.

- ■Phase detection “knows” how far out of focus a subject is. The separation between the two halves of the image let the AF system know whether the subject is grossly out of focus, or whether only a slight adjustment is needed. That means faster autofocus, too.

- ■Phase detection isn’t as dependent on scene brightness. As long as the split images are illuminated well enough for the AF system to make an evaluation, greater or lesser amounts of light don’t have as much of an effect on speed and accuracy. Remember, the reason phase detection systems operate less well at smaller f/stops is because the baseline diameter of the aperture is smaller.

- ■Sony’s 4D high-density tracking can follow moving subjects. The a7 IV’s phase detection system can achieve focus quickly (even when shooting continuously at 10 frames per second), whether your subject is moving horizontally or vertically (what Sony calls area), toward you, or away from you (depth in Sony-speak). To those three dimensions, the system adds the fourth dimension of time (which the company labels as steadfast), so focus can be maintained as it changes position. The 4D AF also deploys high-density tracking to zero in on moving subjects, using focus areas that are smaller than the phase detection sensor areas shown in Figure 4.4.

Focus Modes and Options

Now that you understand the fundamental principles of how the a7 IV achieves focus, let’s discuss the practical application of these principles to your everyday picture-taking activities, by setting the various modes and options available for the autofocus system. We’ll also discuss the use of manual focus, and when that method might be preferable to autofocus.

As you’ve come to appreciate by now, the a7 IV offers many options for your photography. Focus is no exception. Of course, as with other aspects of this camera, you can set the shooting mode to Intelligent Auto or Program mode, and the camera will do just fine in most situations. But, if you want more creative control, the choices are there for you to make.

So, no matter what shooting mode you’re using, your first choice is whether to use autofocus or manual focus. Yes, there’s also a Direct Manual Focus (DMF) option, but that still provides autofocus, with the option of fine-tuning focus manually before taking the shot. Manual focus presents you with great flexibility along with the challenge of keeping the image in focus under what may be difficult conditions, such as rapid motion of the subject, darkness of the scene, and the like. Later in this chapter, I’ll cover manual focus as well as DMF. For now, I’ll assume you’re going to rely on the camera’s conventional AF mode.

The Sony a7 IV has three basic AF modes: AF-S (Single-shot autofocus) and AF-C (Continuous autofocus), as well as Automatic AF (AF-A), which switches between the two other modes as required. Once you have decided on which of these to use, you also need to tell the camera how to select the area used to measure AF. In other words, after you tell the camera how to autofocus, you also have to tell it where to direct its focusing attention.

Focus Pocus

Back in the pre-AF days, manual focusing was problematic because our eyes and brains have poor memory for correct focus, which you often note when you submit to that refractive test at your eye doctor that I mentioned earlier. Similarly, manual focusing involves jogging the focus ring back and forth as you go from almost in focus, to sharp focus, to almost focused again. The little clockwise and counterclockwise arcs decrease in size until you’ve zeroed in on the point of correct focus. What you’re looking for is the image with the most contrast between the edges of elements in the image.

Adding Circles of Confusion

But there are other factors in play, as well. You know that increased depth-of-field brings more of your subject into focus. But more depth-of-field also makes autofocusing (or manual focusing) more difficult because the contrast is lower between objects at different distances. So, autofocus with a 300mm lens (or zoom setting) may be easier than at a 16mm focal length (or zoom setting) because the longer lens has less apparent depth-of-field. By the same token, a lens with a maximum aperture of f/1.8 will be easier to autofocus (or manually focus) than one of the same focal length with an f/4 maximum aperture, because the f/4 lens has more depth-of-field and a dimmer view. It’s also important to note that lenses with a maximum aperture smaller than f/5.6 would give your Alpha’s autofocus system fits, because the smaller opening (aperture) would allow less light to enter or to reach the autofocus sensor.

Technically, there is just one plane within your picture area, parallel to the back of the camera (or sensor, in the case of a digital camera), that is in sharp focus. That’s the plane in which the points of the image are rendered as precise points. At every other plane in front of or behind the focus plane, the points show up as discs that range from slightly blurry to extremely blurry. In practice, the discs in many of these planes will still be so small that we see them as points, and that’s where we get depth-of-field. Depth-of-field is just the range of planes that include discs that we perceive as points rather than blurred splotches. The size of this range increases as the aperture is reduced in size and is allocated roughly one-third in front of the plane of sharpest focus, and two-thirds behind it. The range of sharp focus is always greater behind your subject than in front of it. (See Figure 4.6.)

Figure 4.6 The range of sharp focus is greater behind your subject than in front of it.

To make things even more complicated, many subjects aren’t polite enough to remain still. They move around in the frame, so that even if the camera’s lens is sharply focused on your main subject, the subject may change position and require refocusing. An intervening subject may pop into the frame and pass between you and the subject you meant to photograph. You (or the camera) have to decide whether to focus on this new subject, or to remain focused on the original subject. Finally, there are some kinds of subjects that are difficult to bring into sharp focus because they lack enough contrast to allow the camera’s AF system (or our eyes) to lock in. Blank walls, a clear blue sky, or other low-contrast subject matter may make focusing difficult even with the hybrid AF system.

If you find all these focus factors confusing, you’re on the right track. Focus is, in fact, measured using something called a circle of confusion. An ideal image consists of zillions of tiny little points, which, like all points, theoretically have no height or width. There is perfect contrast between the point and its surroundings. You can think of each point as a pinpoint of light in a darkened room. When a given point is out of focus, its edges decrease in contrast and it changes from a perfect point to a tiny disc with blurry edges (remember, blur is the lack of contrast between boundaries in an image). (See Figure 4.7.)

Figure 4.7 When a pinpoint of light (left) goes out of focus, its blurry edges form a circle of confusion (center and right).

If this blurry disc—the circle of confusion—is small enough, our eyes still perceive it as a point. It’s only when the disc grows large enough that we can see it as a blur rather than as a sharp point that a given point is viewed as being out of focus. You can see, then, that enlarging an image, either by displaying it larger on your computer monitor or by making a large print, also magnifies the size of each circle of confusion. Moving closer to the image does the same thing. So, parts of an image that may look perfectly sharp in a 5 × 7-inch print viewed at arm’s length, might appear blurry when blown up to 11 x 14 inches and examined at the same distance. Take a few steps back, however, and the image may look sharp again.

To a lesser extent, the viewer also affects the apparent size of these circles of confusion. Some people see details better at a given distance and may perceive smaller circles of confusion than someone standing next to them. For the most part, however, such differences are small. Truly blurry images will look blurry to just about everyone under the same conditions.

Your Focus Mode Options

Manual focus can come in handy, as I’ll explain later in this chapter, but autofocus is likely to be your choice in the great majority of shooting situations. Choosing the right AF mode and the way in which focus points are selected is your key to success. Using the wrong mode for a particular type of photography can lead to a series of pictures that are all sharply focused—on the wrong subject.

But autofocus isn’t some mindless beast out there snapping your pictures in and out of focus with no feedback from you. There are several settings you can modify to regain a fair amount of control. Your first decision should be which of the autofocus modes to select: Single-shot (AF-S), Continuous AF (AF-C), or Automatic AF (AF-A). DMF first uses autofocus, and then allows you to fine-tune focus manually. I recommend using the Function menu, where Focus Mode is located in the top row, second from the left.

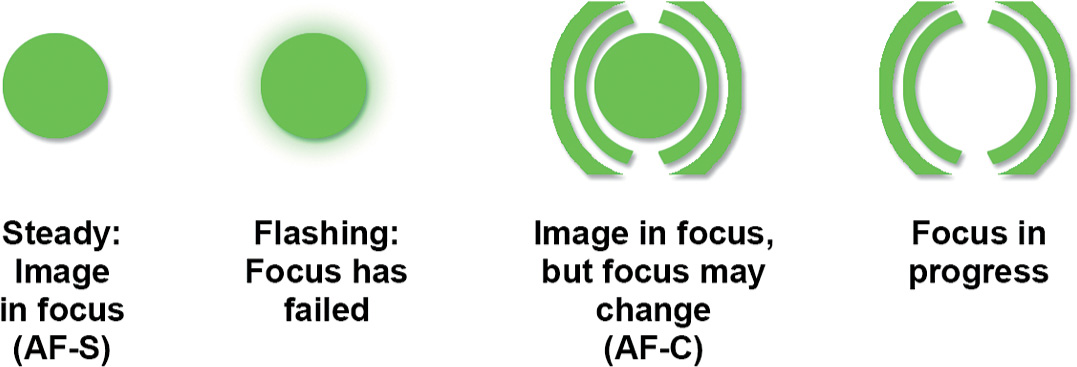

Figure 4.8 The focus indicator icon shows focus status.

In the next sections, I’m going to describe all five focus modes, so you’ll understand exactly what types of subjects each is intended for. However, as you’ll learn, the a7 IV’s AF system is so sophisticated that you can generally set up your camera as I’ll explain later in this chapter in a section called “Magic Autofocus—Set and Forget,” and then forget about twiddling with autofocus thereafter. I’ll list a few settings you can make that will let the a7 IV easily nail autofocus under most conditions more than 90 percent of the time.

Single-Shot AF (AF-S) Mode

With Single-shot AF (AF-S), the camera will lock in focus when you press the shutter release (or an alternate button you’ve assigned the AF start function to) and will not adjust focus if your subject moves or you change the distance between you and your subject, as long as you hold down the button.

In AF-S mode, focus is locked. By keeping the button depressed halfway, you’ll find you can reframe the image by moving the camera to aim at another angle; the focus (and exposure) will not change. Maintain pressure on the shutter release button and focus remains locked even if you recompose, or if the subject begins running toward the camera, for example.

| NOTE In this chapter, I’m assuming that you’re using P, A, S, or M mode where you have full control over the camera features. This is important because the camera will use only AF-S in Intelligent Auto mode. And it will set Continuous AF (AF-C) only in Movie mode, regardless of what focus mode you’ve selected for still images. |

When sharp focus is achieved in AF-S mode, the solid green focus indicator appears in the lower-left corner of the screen and you’ll hear a little beep. One or more green focus confirmation frames will also appear to indicate the area(s) of the scene that will be in sharpest focus.

For non-action photography, AF-S is usually your best choice, as it minimizes out-of-focus pictures (at the expense of spontaneity). Because of the small delay while the camera zeroes in on correct focus, you might experience slightly more shutter lag. This mode uses less battery power than Continuous AF.

If you have activated Pre-AF in Focus > AF/MF menu (it’s the last entry, and you must scroll down to see it), you may notice something that seems strange: the camera’s autofocus mechanism will begin seeking focus even before you touch the shutter release button. In this mode, no matter which AF method is selected, the camera will continually alter its focus as it is aimed at various subjects, until you press the shutter release button halfway. At that point, the camera locks focus, in Singleshot AF mode.

When using AF-S or AF-C (described next), you can specify focus priority, from AF (wait until the subject is in sharp focus), Release (take the picture now even if not in perfect focus), and Balanced Emphasis (compromise!). I will explain setting these options in the Focus > AF/MF menu in more detail in Chapter 8.

Continuous AF (AF-C) Mode

When Continuous AF is active, focus is constantly readjusted as your subject (or you) move. The difference between Single-shot AF and Continuous AF comes at the point the shutter release button (or defined focus start button) is pressed halfway. (See the discussion of back-button focus later in this chapter.)

Switch to this mode when photographing sports, young kids at play, and other fast-moving subjects. In this mode, the camera can lock focus on a subject if it is not moving toward the camera or away from your shooting position; when it does, you’ll see a green circle surrounded by brackets. (There will be no beep.) But if the camera-to-subject distance begins changing, the camera instantly begins to adjust focus to keep it in sharp focus, making this the more suitable AF mode with moving subjects.

Automatic AF (AF-A) Mode

The camera begins using AF-S, and switches to AF-C if the subject begins moving. Use this mode when you’re not certain that your subject will begin moving, and you’d like to take advantage of AF-S, as described earlier, until the subject does move. You might use AF-A to photograph a sleeping pet, which, if awakened by the activity, might respond with sudden movement.

Direct Manual Focus (DMF) Mode

The camera focuses using AF-S mode, then uncouples the focus motor so you can fine tune focus (if necessary) manually. For best results, use this mode with focus peaking enabled to provide you with visual feedback as you adjust.

Manual Focus

No autofocus at all. You’re on your own in deciding when the image is in sharp focus but provided with extra tools, such as the focus indicator in the lower-left corner of the screen (shown earlier in Figure 4.8), focus peaking, and the a7 IV’s focus magnification features.

Focus or Release Priority?

The current focus plane is fixed and cannot be changed at a certain point in the picture-taking process. With AF-S mode, that point is when you press the shutter release halfway. As long as you keep your finger on the button, the camera will not refocus until you press down all the way, or take your finger off the release. In AF-C mode, the camera will focus, but will continue to refocus as long as the shutter release is held down halfway. Focus is not locked until you press down all the way to take a picture.

In either mode, when you simply press the shutter release down all the way, focus activation, locking, and picture taking take place one after the other. That’s where focus/release priority come into play. When the shutter release is pressed down all the way in a continuous motion, do you want the camera to wait until sharp focus is achieved, even if that means missing the exact instant you wanted to capture? Or do you want to have the a7 IV go ahead and take the picture anyway, even if there is a possibility that the image isn’t perfectly focused? I’ll explain how to set the priority options in

Chapter 8, but here’s a preview to using the Priority Set in AF-S/AF-C entries in the Focus > AF/ MF > Priority Set in AF-S/AF-C entries:

- ■AF Priority. The shutter is not activated until sharp focus is achieved. You can choose the AF Priority option for both AF-S and AF-C modes individually. Use AF Priority for subjects that are not moving rapidly. The a7 IV’s AF system is fast enough that the slight delay should be negligible. However, if you’re using an A-mount lens that does not have a built-in AF motor with the EA-LA adapter, you can experience a significant delay. Sports shooters and others who depend on capturing the decisive moment and can countenance no delay at all generally use Release Priority, discussed next.

- ■Release Priority. When this option is selected, the shutter is activated when the release button is pushed down all the way in both AF-S and AF-C modes, even if sharp focus has not yet been achieved. I prefer this option for AF-C mode, as Continuous Focus focuses and refocuses constantly when autofocus is active, and even though an image may not quite be in sharpest focus, at least I am able to get my shot. Using Release Priority does not mean that your image won’t be sharply focused; it just means that the a7 IV hasn’t yet confirmed that focus is achieved. Keep in mind that the a7 IV’s AF system is very speedy, so your picture is likely to be in sharp focus even if the camera hasn’t had quite enough time to confirm that focus is locked in. If you’ve been poised with the shutter release pressed halfway, the camera probably has been tracking the focus of your image.

- ■Balanced Emphasis. In this mode, the shutter is released when the button is pressed, with a slight pause if autofocus has not yet been achieved. It can be selected for both AF-S and AF-C modes, and is probably your best choice if you want a good compromise between speed of activation and sharpest focus. However, you would not want to use this setting if the highest possible continuous shooting rates are important to you.

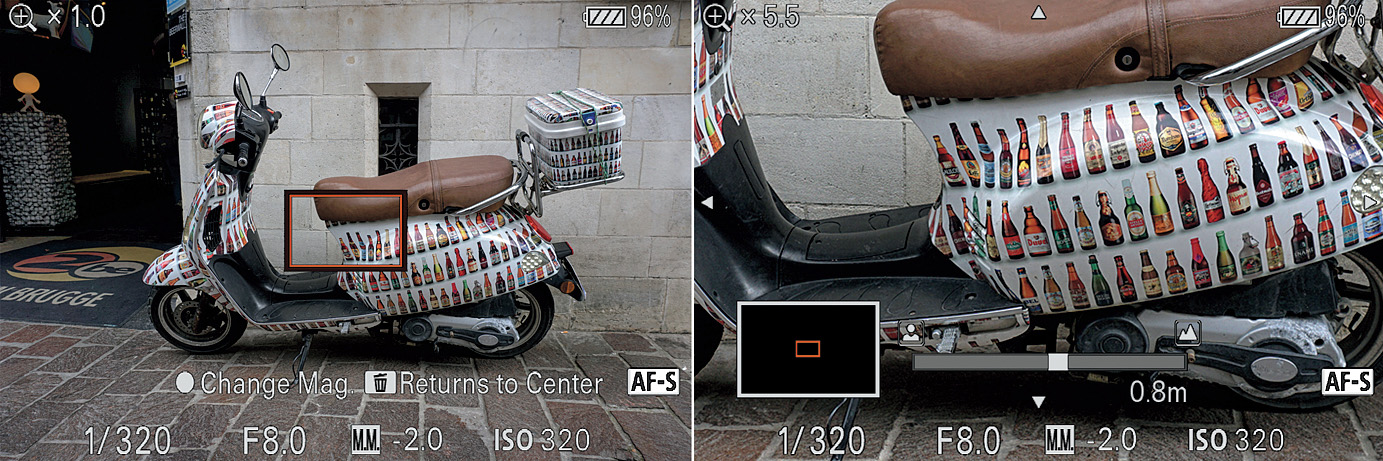

Autofocus Magnified

Your a7 IV has several focusing aids that are activated when you use Manual focus. One of them is a Focus Magnifier tool, which also happens to work perfectly well in autofocus mode. The magnifier can be invoked to enlarge your image so the AF system can more easily zero in on your subject. All you need to do is create a custom key that will produce the Focus Magnifier on demand. Just follow these steps:

- 1.Define a custom key, as the activating button for Focus Magnifier. You’ll find instructions for creating custom keys using the Setup > Operation Customize > Custom Key/Dial Settings entry in Chapter 9. I won’t repeat that information here. Select a button of your choice and choose Focus Magnifier as its custom operation.

- 2.Press the Focus Magnifier custom key. An orange box will appear on the screen. (See Figure 4.9, left.) Use the directional buttons to position the orange box over the area you want to bring into focus.

- 3.Press the center button. The Focus Magnifier will enlarge the image contained within the orange box by a factor of 5.5X. (See Figure 4.9, right.) Press the center button a second time to enlarge 11X, if needed.

Figure 4.9 Activate focus magnifier (left) and focus on zoomed-in area (right).

- 4.Activate AF. Press the shutter release halfway to activate autofocus (or use another key you may have defined to perform that function, say, if you’re using back-button focus as described later in this chapter).

- 5.AF focus commences. The a7 IV will use the current AF settings to focus on the area you’ve selected with the orange box.

Choosing the AF Area

So far, you have allowed the camera to choose which part of the scene will be in the sharpest focus using its focus detection points (called AF areas by Sony). However, you can also specify a single focus detection point that will be active. The Custom 2 (C2) button will summon Focus Area if you haven’t redefined it to another behavior. You can also specify focus area using the Function menu, using the third icon from the left in the top row. Here is how the AF Area options work:

- ■Wide. The camera chooses the appropriate focus area(s) in order to set focus on a certain subject in the scene. There are no focus indicators visible on the screen until you press the shutter release button halfway. At that point, in AF-S mode, the camera displays one or more green focus indicators to show what area(s) of the image it has used to set focus on. In AF-C mode, the indicators will continue to flicker around the frame while the camera refocuses as necessary. If Face Detection is active, the AF system will prioritize faces when making its decision as to where it should set focus. You’ll see multiple focus indicators when several parts of the scene are at the same distance from the camera. When most of the elements of a scene are at roughly the same distance, the camera displays a single, large green focus bracket around the entire edge of the screen.

- Even if you set one of the other options, Wide is automatically selected in Intelligent Auto mode. Use this mode to give the camera complete control over where to focus. You can activate AF/ MF > Focus Area > AF-C Area Display, as described in Chapter 8, if you want to see the focus area displayed as you use AF-C. Indeed, if you’re working with AF-C, you’ll see the high-density points “dance” as the a7 IV continually refocuses as your subject or camera moves.

Figure 4.10 With Wide AF Area, the camera either displays a large green bracket indicating that most of the scene is at the same distance to the camera (left) or it displays one or more smaller brackets to indicate the specific area(s) of the scene that will be in sharpest focus (center). If the camera decides that all areas of the frame should be considered, a bracket around the entire focusing area is shown (right).

- ■Zone. There are nine different focus zones available—three at the top left, center, and top right of the frame, three in the equivalent positions at the bottom, and three in the middle. Each of those zones is populated by a 9 × 9 array of focus points, as shown in Figure 4.11.

- You can move the focus array to one of the nine overlapping areas using the directional buttons while those brackets are displayed. To lock the brackets in their current position, press the center button (or other defined Focus Standard button). Press the center button again to resume moving the frames. You can also move the focusing frame quickly with the touch screen and return the zone to the center of the screen by pressing the Trash button.

- Press the AF-ON button or press the shutter release halfway to initiate focus. The display changes to one of the three modes described in the Vanishing Brackets sidebar above, and the camera chooses which sections within the zone to use to calculate sharp focus. The active focus points will be highlighted in green. Use this mode when you know your subject is going to reside in a largish area of the frame and want to allow the a7 IV to select the exact focus point within your designated zone.

Figure 4.11 In Zone mode, brackets represent a focus zone, and you can move the zone to nine different locations on the screen. The camera selects one or more focus points within that array.

Figure 4.12 In the Center Fix Area mode, the camera displays the focus brackets in the center of the screen; the brackets turn green after focus has been set.

- ■Center Fix. Activate this AF area and the camera will use only a single focus detection point in the center of the frame to set focus. Initially, a pair of black focus brackets appears on the screen. Touch the shutter release button and the camera sets and locks focus on the subject in the center of the image area; the brackets then turn green to confirm the area that will be in the sharpest focus in your image. Choose this option if you want the camera to always focus on the subject in the center of the frame. (See Figure 4.12.) Center the primary subject (like a friend’s face in a wide-angle landscape composition), allow the camera to focus on it, maintain slight pressure on the shutter release button to keep focus locked, and re-frame the scene for a more effective, off-center, composition. Take the photo at any time and your friend (who is now off-center) will be in the sharpest focus.

- ■Spot. This mode enables you to move the camera’s focus detection point (focus area) around the scene to any one of multiple locations, using the directional buttons. When opting for Spot, you can use the left/right buttons to choose Small, Medium, or Large spots, which changes the size of the focus brackets in the frame. This mode can be useful when the camera is mounted on a tripod and you’ll be taking photos of the same scene for a long time while the light is changing, for example. Move the focus area to cover the most important subject, and it will always focus on that point when you later take a photo.

- Use the multi-selector joystick to move the brackets around the screen, which allows great versatility in the placement of the active focus detection point. (See Figure 4.13.) Adjust the brackets until they cover the most important subject area and touch the shutter release button. The brackets will turn green and the camera will beep to confirm that focus has been set on the intended area.

- ■Expand Spot. If the camera is unable to lock in focus using the selected focus point, it will also use the eight adjacent points to try to achieve focus.

- ■Tracking AF. In this mode, the camera locks focus onto the subject area that is under the selected focus spot when the shutter button is depressed halfway. Then, if the subject moves (or you change the framing in the camera), the camera will continue to refocus on that subject. You can select this mode only when the focus mode is set to Continuous AF (AF-C).

Figure 4.13 When the Spot AF Area mode is initially selected, the active focus detection point is delineated with indicators that turn green when focus is confirmed and locked. Use the multiselector or touch screen to specify location of the spot.

Figure 4.14 Choose a subject to track.

This option is especially powerful, because you can activate it for any of the focus area options described above. That is, once you’ve highlighted Tracking on the selection screen, you can then press the left-right directional button and choose Wide, Zone, Center Fix, Spot, or Expand Spot. The camera will lock on a subject, using one of those area modes to follow it. (See Figure 4.14 and the explanation which follows in the next section.)

You cannot use this option if the Still/Movie/S&Q dial is set to Movies or S&Q quick-/slow-motion video shooting movies. I’ll describe Tracking AF, along with eye/face recognition in more detail in the section that follows this one.

Just as you’re limited in the use of the AF mode in certain operating modes, there’s a limitation with AF Area as well. For example, Spot is not available for selection in Intelligent Auto mode; the camera will always use Multi as the AF Area mode.

Tracking and Focusing on Subjects, Faces, and Eyes

The a7 IV’s tracking capabilities are awesome enough on their own. The camera’s upgraded face and eye detection augments the plain vanilla tracking capabilities enough that it can be considered one of the most significant improvements this camera boasts.

Tracking AF is not limited to following and focusing on faces or eyes, of course; it can track any moving subject. In general, you can turn it on and forget it. Conventional tracking does, however, only work in still photography mode; you can’t use it when shooting movies. When the Still/Movie/S&Q dial is set to the Movie position, the Tracking focus area mode is not available.

However, that doesn’t mean tracking is totally unavailable in Movie mode; you can still use the touch screen to specify a subject to be tracked. Navigate to the Setup > Touch Operation > Touch Function in Shooting and set to Touch Tracking. Then, you can simply tap a subject on the LCD screen and the a7 IV will track it. However, if you later want to use Touch Focus in stills mode, you’ll want to return to the Function of Touch Operation entry and revert to Touch Focus when you’re finished shooting video.

One thing to keep in mind is that it’s sometimes difficult to track subjects other than humans; if your chosen subject happens to be near a face (say, an active pet, when you have the Animal or Bird subject options turned off), the a7 IV’s AF system will sometimes jump to the face/eyes, and begin tracking it, instead. The desired subject needn’t be physically near the face; proximity in two-dimensions is sufficient to fool the AF system. Perhaps you want to photograph a close-up of a bride’s hand wearing her new wedding ring, with the groom smiling in the background. If the groom’s face is “close” enough to the ring in the frame, instead of a sharp photo of the bridge’s hand and a smiling groom (who you wanted to be out of focus for creative effect), you end up with a sharp husband and blurry wedding ring.

Tracking may not work if the subject is moving too quickly, is too small or too large to be isolated effectively, has only reduced contrast against its background, or if the ambient light is too dark or changes dramatically while you’re tracking. I’m going to show you how to use the basic tracking feature first, then go into detail about the new face/eye detection features.

However, to use the full range of options available with Tracking AF, you can follow these steps, which do require choosing AF-C as your focus method:

- 1.Choose AF-C. Tracking works only when you are using continuous autofocus because, well, it refocuses continually.

- 2.Activate Tracking AF. Use the Function menu and choose Focus Area. Scroll down to the bottom of the list of modes and highlight Tracking.

- 3.Choose Focus Area Mode. Using Tracking does not mean you lose access to the four AF area modes. With Tracking highlighted, use the left/right directional controls to select Wide, Zone, Center Fix, Spot (S, M, or L), or Expand Spot. That will give you both Tracking AF and the area mode you prefer. If you switch from AF-C to AF-S, you lose the lock-on capabilities, and the camera just reverts to whatever focus area mode you select here.

- 4.Select subject to track. Your subject will be within the selected autofocus area.

- •Tracking: Wide. The camera selects the focus area and subject to track.

- •Tracking: Center Fix. Frame the scene so the subject you want to track is under the center focus point.

- •Tracking: Spot. You can use the directional controls to position the Small, Medium, or Large Spot over the subject.

- •Tracking: Expand Spot. You can use the directional controls or touch screen to position the Small, Medium, or Large Spot over the subject. (See Figure 4.15, left.)

- 5.Start tracking. When you activate focus by pressing the shutter release halfway, the camera will use your selected focus area option to lock in focus, as always. However, now, once focus has been locked, the camera will track your subject as it roams around the screen. You’ll see the green focus area box moving as your subject moves (or you reframe the image with the camera). (See Figure 4.15, right.) If a face is detected, a tracking rectangle around the face will be shown. (You’ll learn more about face detection in an upcoming section.)

Figure 4.15 Left: Place the focus point on the object the camera should track and press the shutter release to activate tracking. Right: When Tracking is active, the camera maintains focus on your preferred target, tracking it as it moves around the scene.

Face Detection and Eye AF Overview

As hinted already, the a7 IV has a couple more tricks up its sleeve for setting the AF area. The camera can detect faces and eyes, lets you select which eye to track, and can differentiate between humans and animals—and it can do all that at high speed! You can turn Face Priority on or off and activate visible frames around the faces the a7 IV detects. This enables the camera to attempt to identify any human faces in the scene. If it finds one or more faces, the camera will surround each one (up to eight in all) with the highest priority face outlined in white, and the others in either gray (if an unregistered face) or purple (if you have previously registered that face). In AF-S mode, an additional frame will be placed on the eyes of your subject, if detected. Press the shutter release halfway and the camera focuses on the highest priority face.

You can also specify Face Priority in Multi Metering in the Exposure/Color > Metering group, and the a7 IV will not only try to focus on faces, it will base its exposure on them as well. (It’s locked to On when using Intelligent Auto.) This feature is disabled when Focus > Face/Eye Subject is set to Animal or Bird.

Face/Eye Detection is disabled when using digital zoom features, and the focus magnifier. It’s also unavailable when shooting movies with the 120p/100p Record Setting, S&Q slow-motion movies at 120/100 frames per second, or when capturing 4K movies at 30/25p 100M or 30/25p 60M.

Making Your Face/Eye Detection Settings

The key Face/Eye Detection settings are found in several different menus. This section will help you find and adjust all of them. I’ll show you how to tell the a7 IV to base its AF decisions on faces, give certain faces a higher priority, and explain how to switch back and forth between detecting human eyes and those of animals or birds. Your first stop should be the Focus > Face/Eye AF group, which has six menu entries (See Figure 4.16):

Figure 4.16 Focus > Face/Eye AF group.

- ■Face/Eye Priority in AF. The entry has two choices: On or Off. When set to Off, the camera gives no special priority to faces detected within the frame. Perhaps you’re shooting landscapes or other scenes and don’t want the camera to fixate on any faces it detects.

- Alternatively, choose On and the a7 IV will give a higher priority to detected faces. Up to eight faces, if present, may be detected. When autofocus is activated, the camera will attempt to focus on the eyes, if they are located within the active focus area. Note that when using Intelligent Auto, Face/Eye Priority is locked at On.

- They Eye AF portion of Face/Eye Priority AF may not function as expected with subjects which are rapidly moving, have long bangs, closed eyes, or are wearing sunglasses. Shady conditions, backlight, and low-light situations can also hinder eye detection. Keep in mind that if the a7 IV is unable to focus on human eyes in the frame for some reason, it will fall back to focusing on the human’s face instead. (This is useful with humans who have their eyes closed, are wearing some kinds of glasses, or who have hair that obscures their eyes. You can generally count on having to manually focus Saul “Slash” Hudson.)

- ■Face/Eye Subject. When set to Human, the camera looks for human faces and eyes. If you choose Animal or Bird instead, it looks for animal/bird eyes only; as, to date, the faces of other types of living creates vary too much for existing technology to detect with any reliability. It’s generally safe to leave this setting at Human, unless you happen to be at a zoo, photographing the Westminster Kennel Club show, or engaged in other animal-intensive activities. (Animal/Bird eye detection works great, by the way.)

- ■Subject Selection Setting. This setting allows you to disable one or more of the subject possibilities, Human, Animal, or Bird. For example, if you rarely shoot birds, you can disable that choice so the a7 IV will switch only between Human or Animal subjects using the Face/Eye Subject entry above.

- ■Right/Left Eye Select. Chooses whether to detect the left or right eye of the human subject (the option is not available when Animal is selected for Subject Detection). Note that this feature uses the subject’s eye, which may be on the opposite side from your perspective (that is, your subject’s right eye is on the left side of your frame). In general, it usually doesn’t matter which eye the camera scrutinizes. If you don’t care (which will usually be the case), select Auto instead of Right or Left, and the a7 IV will do a good job of finding the closest eye for you.

- One really cool thing to do (because you can!) is to assign Switch Right/Left Eye to a Custom Key in the Setup > Operation Customize > Custom Key Setting (Stills) entry, just to have the power to alternate eyes on the fly if you feel the need.

- ■Face/Eye Frame Display. When activated, the camera automatically shows a small white square around a human eye it is focusing on, and that frame will turn green when the subject is in focus. But you can also enable a frame around entire faces with this option. (If you want the frames to display, but disappear after a time, use AF Area Auto Clear, described later in this chapter.)

- Although the eye-focus box is helpful, I find the additional box around the face very useful and leave it on at all times so I know exactly what face(s) has been detected. When enabled, a gray selection box appears around detected faces. The box around the face used for autofocus turns white. If there are several faces in the frame and you’ve registered and prioritized some or all of them, the boxes around the other faces turn reddish-purple. (I’ll show you how to register faces later in this chapter.) If you find the boxes distracting, you can turn them off, and face detection, if enabled, as described earlier, will still be active.

- ■Face Memory. You can tell your a7 IV which faces are near and dear to your heart using this entry, which allows you to register up to eight different faces. I’ll show you how to capture and prioritize faces in Chapter 8. You can change the preferred order of importance at any time.

- ■Register Faces Priority. This entry lets you enable/disable use of face priority at will. If you’re photographing an event and don’t want to prioritize certain faces (say, you’re at a cousin’s wedding reception and would rather not highlight your immediate family who might be in some of the photos), you can disable registered face priority.

Other Important Face/Eye Settings

There are several other settings you need to keep in mind when using Face/Eye Detection:

- ■Exposure/Color > Metering > Face Priority in Multi Metering. Since the a7 IV does such a good job in finding faces, you might as well leverage that capability to improve your exposure metering, too, when you’re photographing people. This entry tells the a7 IV to adjust its Multi metering to prioritize exposure for any faces in the scene. It works especially well for street photography and some kinds of performances.

- ■Eye AF. You can assign Eye AF to a button using the Custom Key (Stills) entry in the Setup > Operation Customize group. After assigning the Eye AF function to a key, the a7 IV will detect and focus on the eye as long as you are holding down the custom key. The camera will search for human eyes within the entire frame, regardless of the Focus Area you’ve selected. Press the shutter release down all the way while holding the key to take the picture. It also allows you to use one Focus Area setting, and instantly bypass that selection by activating Eye AF. I also noted earlier that you can assign a key to Right/Left Eye select, bypassing the Auto setting for that feature if your subject tends to not face you consistently.

Magic Autofocus—Set and Forget

I gave this chapter the title “Mastering Autofocus Options” for a reason. Your Sony a7 IV has an incredible number of autofocus adjustments. My goal, to this point, has been to help you learn about all those options so you’ll understand exactly what you can do to fine-tune the a7 IV’s incredible AF features under a variety of situations.

The good news is that your camera’s AF system is so robust, you may not need to implement many features for about 90 percent of your shooting. This section will explain some basic adjustments you can set, and then forget, for most of your shooting. The a7 IV can do an excellent job of achieving focus under most conditions; my camera stumbles only under very low-light environments, insanely active sports, or with challenging subjects like birds in flight. Not that it can’t perform well in those situations, but you can still benefit from the AF options described earlier in this chapter.

Here’s the secret of “magic” autofocus, which I think you’ll find will work very well nearly all of the time, thanks to the a7 IV’s generous array of phase detect AF points embedded in the sensor, contrast detect zones, and the pure power of its Bionz XR microprocessor:

- ■Set your AF mode to AF-C. Leave it there. Advanced users don’t need the “automatic” AF-A mode, which is inconsistent. You might need AF-S if you want to lock focus on a particular subject. I’m going to show you how you can leave the camera set on AF-C and still temporarily switch from AF-C to AF-S when you hold down a Custom Key.

- ■Set AF Area mode to Tracking: Spot M. Thereafter, you can move the box representing the focus spot around the screen with the multi-selector joystick. Half-press the shutter release button and the a7 IV will begin tracking whatever is under the spot location as long as you continue to hold the shutter button.

- Here’s the cool part: If there is a human in the area you decide to track, the a7 IV will add Face/ Eye detection to improve its AF performance. If the area you track does not have a human, the camera will track that object instead. It will continue to detect faces and eyes, but won’t automatically focus on them. This is the “feature” I noted in the “A Useful Bug” sidebar earlier. Most other camera brands with face detection don’t give you this flexibility. It makes it possible to track objects that are not human without disabling face detection—as long as the human face isn’t too close to the tracked subject.

- ■Activate Face/Eye Priority in AF. I showed you how to do this in the previous section.

- ■Set Subject Detection to Human and Right/Left Eye Detect to Auto. Change these only if you have a reason to switch to Animal, Bird, or specific eye detection.

- ■Enable Face/Eye Frame Display. You’ll appreciate the extra feedback and reassurance.

- ■Begin to enjoy amazingly accurate AF. You may find you rarely have to make most of the adjustments described earlier in this chapter—although you’ll be able to once you’ve learned how and when to use each of them.

- ■If you need to lock focus. switch to manual focus, or temporarily switch to AF-S using the technique described next.

Your AF-C to AF-S Switch

Sony doesn’t offer a Custom Key definition to toggle between AF-C and AF-S, but you can do the next best thing—define a button so that the camera switches to AF-S while you hold down the button and then switches back to AF-C once you release it.

The procedure is fairly simple. Just follow these steps:

- 1.Access Register Custom Shoot Set. Navigate to Shooting > Shooting Mode > Register Custom Shooting Setting (described in more detail in Chapter 6 if you need some coaching).

- 2.Select a Custom Shoot Set to register. I selected Recall Custom Hold 1. Press the center button to enter the setup screen.

- 3.Unmark all but two settings. A wide variety of camera settings can be registered, but for this application we don’t want to mess with most of your camera’s settings. We only want to change the Focus Mode and Focus Area settings, and only while the defined Custom Key is pressed. Scroll through the list and unmark all of them except for Focus Mode and Focus Area.

- 4.Specify each of the two. Highlight Focus Mode and select Single-shot AF from the screen that appears. Then Highlight Focus Area, and choose Center.

- 5.Select Register. Scroll down to the bottom of the settings list and highlight Register. Press the center button to confirm your settings, and MENU to exit.

- 6.Navigate to Setup > Operation Customize and choose Custom Key (Stills).

- 7.Define the button you want to use to switch temporarily to AF-S. I chose the Multi-selector center button.

- 8.When your button is highlighted press the center button, and in the screen that appears navigate to the Recall Custom Hold 1 option.

- 9.Press enter to confirm. Then press MENU to exit.

That’s all there is to it. Henceforth, AF-C, Tracking, and Face/Eye Detection will by default be active and provide amazing AF performance under most circumstances. If you want to switch to AF-S to lock in focus on a specific subject, just press your defined Custom Key (in my case the multi-selector button) and hold it down. Then, press the shutter release halfway. The a7 IV will use Single-shot (AF-S) to focus and the Focus Area will be set to the center of the screen. The camera will lock focus as long as you keep the Custom Key and shutter release depressed. To return to AF-C and your other previous AF settings, just release the Custom Key.

Understanding Aperture Drive in AF

If you used digital SLRs prior to switching to mirrorless cameras, there may be a difference in the way your new camera’s aperture behaves when focusing. Single-lens reflex cameras have traditionally focused with the lens aperture set to its maximum (widest) position. That provides a big, bright image and the shallowest depth-of-field the lens is capable of at that focal length. At the moment of exposure, the lens stops down to the “taking” or shooting aperture (which is specified by you or the camera’s autoexposure system) and the mirror flips up so the shutter can open and take the photo.

The iris of your a7 IV behaves in a much more complicated way. That’s necessary because your image preview is produced from the actual sensor image, whether you are using the viewfinder or LCD monitor, and the image you see is affected by how large or how small the current aperture is. The camera’s designers made some trade-offs in how the aperture opens and closes before and during exposure. Here’s a quick description:

- ■AF-S mode. When using Single-shot AF, the camera has plenty of time to achieve focus, so in what Sony calls Standard mode, AF is achieved with the aperture set to wide open (but not wider than f/2, if you happen to be using, say, a lens with an f/1.4 maximum aperture).

- ■AF-C mode. When using Continuous AF, in Standard mode, the iris remains closed down during focus. The camera’s AF mechanism has a dimmer view (but can brighten the display for your benefit). However, by retaining the shooting aperture during the constant focusing and refocusing that happens during Continuous AF, your a7 IV avoids the rapid opening/closing of the iris, and its attendant noise. The downside is that under low-light conditions or when the shooting aperture is small, both the CDAF and PDAF systems are handicapped.

The Focus > AF/MF > Aperture Drive in AF entry provides a partial solution. Sony retains the Standard aperture drive system I just described, but adds new Focus Priority and Silent Priority modes you can select. Here are the differences:

- ■Standard. This default mode performs as I’ve described above. Most people will want to retain that setting under most circumstances.

- ■Focus Priority. At this setting AF-S functions as before, but AF-C mode is forced to focus nominally wide open (and never wider than f/2). In practice, the camera doesn’t necessarily dilate the iris all the way; it partially opens, depending on light levels. That means in bright daylight the aperture may not open much at all, because the camera has enough illumination to focus quickly without resorting to a wider f/stop. Under darker conditions, the iris tends to open much wider for focusing, which means AF can be significantly faster under low-light conditions.

- Unfortunately, while AF is faster, this Focus Priority setting introduces a certain amount of shutter lag—the time between when you press the shutter down all the way, and when the picture is actually taken. If you want to improve AF under low light and can accept some shutter lag, give this setting a try.

- ■Silent Priority. The a7 IV always focuses at the shooting aperture, in both AF-S and AF-C focus modes, avoiding the noise of the iris opening and closing repeatedly.

Using Manual Focus

Manual focus is not as straightforward as with an older manual focus 35mm SLR equipped with a focusing screen optimized for this purpose and a readily visible focusing aid. But Sony’s designers have done a good job of letting you exercise your initiative in the focusing realm, with features that make it easy to determine whether you have achieved precise focus. It’s worth becoming familiar with the techniques for those occasions when it makes sense to take control in this area.

Here are the basic steps for quick and convenient setting of focus:

- ■Select Manual Focus. After you do so using the Fn menu or Focus > AF/MF/Focus Mode entries, the letters MF will appear in the LCD display when you’re viewing the default display that includes a lot of data. (You can change display modes by pressing the DISP button.)

- ■Aim at your subject and turn the focusing ring on the lens. As soon as you start turning the focusing ring, the image on the LCD is enlarged (magnified) to help you assess whether the center of interest of your composition is in focus. (That is, unless you turned off this feature using the Focus > Focus Assistant > Auto Magnifier in Manual Focus entry.) Use the up/down/left/right directional controls to move around the magnified image area until you’re viewing the most important subject element, such as a person’s eyes. Turn the focusing ring until that appears to be in the sharpest possible focus.

- The enlargement lasts two seconds before the display returns to normal; you can increase that to five seconds or No Limit with the Focus Magnification Time entry in the same Focus Assistant group.

- ■If you have difficulty focusing, zoom in if possible and focus at the longest available focal length. If you’re using a zoom lens, you may find it easier to see the exact effect of slight changes in focus while zoomed in. Even if you plan to take a wide-angle photo, zoom to telephoto and rotate the ring to set precise focus on the most important subject element. When you zoom back out to take the picture, the center of interest will still be in sharp focus.

- ■Use Peaking of a suitable color. On by default in Shooting mode, focus peaking provides a colored overlay around edges that are sharply focused; this makes it easier to determine when your subject is precisely focused. The overlay is white, but you can change that to another color when necessary. The alternate hue may be needed to provide a strong contrast between the peaking highlights and the color of your subject. Access the Focus > Peaking Display Group to adjust the color. To make the overlay even more visible, select High in the Peaking Level item; you can also turn peaking Off with this item, if desired. You’ll find more on Peaking in Chapter 8.

- ■Consider using the DMF option. Another option is DMF, or Direct Manual Focus. Activate it and the camera will autofocus with Single-shot AF and lock focus when you press the shutter release button halfway. As soon as focus is confirmed, you can turn the focusing ring to make finetuning adjustments, as long as you maintain slight pressure on the shutter release button. The MF Assist magnification will be activated immediately.

- This method gives you the benefit of autofocus but gives you the chance to change the exact point of focus, to a person’s eyes instead of the tip of the nose, for example. This option is useful in particularly critical focusing situations, when the precise focus is essential, as in extremely close focusing on a three-dimensional subject. Because depth-of-field is very shallow in such work, you’ll definitely want to focus on the most important subject element, such as the pistil or stamen inside a large blossom. This will ensure that it will be the sharpest part of the image.

Back-Button Focus

Once you’ve been using your camera for a while, you’ll invariably encounter the terms back focus and back-button focus and wonder if they are good things or bad things. Actually, they are two different things, and are often confused with each other. Back focus is a bad thing and occurs when a particular lens consistently autofocuses on a plane that’s behind your desired subject. Fortunately, that’s a malady only cameras with outboard AF sensors have, so you won’t experience back or front focus unless you’re using an EA-LA2 or EA-LA4 A-mount adapter.

Back-button focus, on the other hand, is a tool you can use to separate two functions that are commonly locked together—exposure and autofocus—so that you can lock in exposure while allowing focus to be attained at a later point, or vice versa. It’s a good thing, although using back-button focus effectively may require you to unlearn some habits and acquire new ways of coordinating the action of your fingers.

As you have learned, the default behavior of your camera is to set both exposure and focus (when AF is active) when you press the shutter release down halfway. When using AF-S mode, that’s that: both exposure and focus are locked and will not change until you release the shutter button or press it all the way down to take a picture and then release it for the next shot. In AF-C mode, exposure is locked and focus is set when you press the shutter release halfway, but the a7 IV will continue to refocus if your subject moves for as long as you hold down the shutter button halfway. Focus isn’t locked until you press the button down all the way to take the picture. In AF-A mode, the camera will start out in AF-S mode but switch to AF-C if your subject begins moving.

What back-button focus does is decouple or separate the two actions. You can retain the exposure lock feature when the shutter is pressed halfway, but assign autofocus start and/or autofocus lock to a different button. So, in practice, you can press the shutter button halfway, locking exposure, and reframe the image if you like (perhaps you’re photographing a backlit subject and want to lock in exposure on the foreground, and then reframe to include a very bright background as well).

But, in this same scenario, you don’t want autofocus locked at the same time. Indeed, you may not want to start AF until you’re good and ready, say, at a sports venue as you wait for a ballplayer to streak into view in your viewfinder. With back-button focus, you can lock exposure on the spot where you expect the athlete to be and activate AF at the moment your subject appears. The a7 IV gives you a great deal of flexibility, both in the choice of which button to use for AF, and the behavior of that button. You can start autofocus, lock autofocus at a button press, or lock it while holding the button. That’s where the learning of new habits and mind-finger coordination comes in. You need to learn which back-button focus techniques work for you, and when to use them.

Back-button focus lets you avoid the need to switch from AF-S to AF-C when your subject begins moving unexpectedly. Nor do you need to use AF-A and hope the camera switches when appropriate. You retain complete control. It’s great for sports photography when you want to activate autofocus precisely based on the action in front of you. It also works for static shots. You can press and release your designated focus button, and then take a series of shots using the same focus point. Focus will not change until you once again press your defined back button.

Want to focus on a spot that doesn’t reside under one of the a7 IV’s focus areas? Use back-button focus to zero in focus on that location, then reframe. Focus will not change. Don’t want to miss an important shot at a wedding or a photojournalism assignment? If you’re set to focus priority, your camera may delay taking a picture until the focus is optimum; in release priority there may still be a slight delay. With back-button focus you can focus first and wait until the decisive moment to press the shutter release and take your picture. The a7 IV will respond immediately and not bother with focusing at all.

Activating Back-Button Focus

To enable back-button focus, just follow these steps:

- 1.Select an AF-ON button. The a7 IV’s built-in AF-ON button performs this function by default, but if you don’t care for its location next to the viewfinder, you can redefine the AEL button or another key. In the Setup > Operation Customize > Custom Key (Stills) entry, define the button of your choice.

- 2.Turn off shutter button AF activation. In the Focus > AF/MF > AF with Shutter entry, set AF/w Shutter to Off. When you want to disable back-button focus (temporarily or permanently), change it back to On.

That’s all there is to it. Henceforth, pressing the shutter release will not activate autofocus. Autoexposure metering will still be initiated by pressing the button halfway, as long as Exposure/Color > Metering > AEL/w Shutter is set to Auto or On (and not Off) and pressing it all the way takes a picture.