9. Design for Habits

(IN WHICH WE LEARN THE IMPORTANCE OF PROVIDING THE ELEPHANT WITH A PLAN AND A WELL-WORN PATH)

What Is a Habit?

A habit is defined as “an acquired behavior pattern regularly followed until it has become almost involuntary.”

We all have a general sense of what habits are, but let’s take a look at how habits can be part of proficiency.

The Story of Two Project Managers

Linda and An Mei are project managers for a software development company.

Both of them are certified Project Management Professionals (PMPs), and both have been project managers for several years. And both are having a challenging week. Take a look at how they responded to some of the daily challenges in being a project manager.

Challenge: A contractor is claiming he didn’t know the due date for a deliverable.

Challenge: Developers coming late to a meeting.

Challenge: A client needs an update to an old project.

The difference between An Mei and Linda isn’t necessarily knowledge. Both project managers have mastered the practice of project management well enough to pass the PMP exam, which is not an easy test.

The difference between them seems to be more about their habits of communication, organization, and vigilance. That’s certainly been my experience working with project managers.

So how does habit design intersect with learning design? If good habits are crucial for success, then how do we help support the development of those habits?

The Anatomy of a Habit

So we looked at the definition of a habit (“an acquired behavior pattern regularly followed until it has become almost involuntary”), but it may be useful to break that down a bit more.

• An acquired behavior pattern. We typically need to learn the behavior that we want to make a habit. We aren’t born with an instinctive desire to floss our teeth, for example; it’s something we need to learn. Like many habits, though, flossing isn’t a particularly complicated behavior to learn. It’s pretty simple, and there isn’t a lot of art to it. But it’s clear that teaching someone to floss isn’t going to magically transform them into a daily flosser. So learning the habit may be a necessary but not sufficient condition for acquiring the habit.

• Triggers. Most models of habit acquisition involve identifying the trigger that activates the habit. It could be a trigger that you are arbitrarily attaching to the new behavior (“When I get my first cup of coffee in the morning, I will take my vitamins”), or it could be a trigger that naturally occurs in in the course of daily life (“When one of my direct reports emails me a deliverable, I will take a few minutes to give them feedback”). An “almost involuntary” behavior needs to have something that activates it. BJ Fogg, of the Persuasive Technology Lab at Stanford, has triggers as a key part of his behavior model (behavior = motivation + ability + trigger).

• Motivation. All the motivation issues discussed in Chapter 8 apply here, autonomy in particular. No one can be told a habit. A habit may be a requirement of someone’s job, and a required action over time can become automatic, but many desirable workplace habits are only going to become routine if the person is actively motivated, which means that that person needs to have autonomy and control over the process. And motivation alone does not mean a habit will be formed, or everyone would still be using that gym membership they got after New Year’s.

• Feedback. The most difficult habits to acquire are frequently the ones that lack any visible feedback. In his book The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg talks about how the addition of substances like citric acid and mint oil to Pepsodent created a tingly clean feeling that reinforced the action of brushing (despite the fact that the tingly compounds don’t actually impact cleanliness). Habits for which the feedback is delayed or absent are frequently the hardest habits to acquire. For example, unless you are fortunate enough to get an immediate endorphin rush from the act of exercise, it may be weeks or months before you start to see the benefits of daily jogging. It’s difficult to persist in an activity with no visible benefit, so most people starting an exercise program will attempt to measure or quantify their progress in some way. Fitness trackers such as the Fitbit are a way to ensure that you can see progress much more quickly.

• Practice or Repetition. Using our definition, something can’t be classified as a habit until it’s “regularly followed until it has become almost involuntary.” We’ve probably all heard metrics for how long it takes to acquire a habit—seven times, or twenty-one days—but unfortunately the real answer is that it depends. It depends on the complexity and difficulty of the behavior, on the mechanisms set up to support it, on the presence of feedback, and on the motivation of the person forming the habit.

• Environment. One of the other determiners of habit formation is how well the environment supports the habit. We’ll discuss this further in Chapter 11, but if I’m trying to acquire the habit of flossing, I dramatically improve the likelihood that I’ll floss if I have a ready supply of dental floss at the necessary time and place. A supportive environment can also include creating social supports—for example, an exercise partner or someone you report back to who keeps you accountable. Breaking an undesirable habit can involve removing the triggers from the environment.

A friend wanted to break the habit of spending too much time on her smartphone before bed. She found herself staying up later and later because of the digital distraction. She could keep the phone out of the bedroom altogether (in the same way that some people trying to break the habit of distracted driving start putting their phones in the trunk when they drive somewhere), but she had family members who would sometimes need to reach her at night, so she wanted to be able to hear the phone ring. She settled on putting the phone in box on her bedside table—it was close enough to hear, but because she didn’t have the visual trigger of the phone, she was much less likely to idly pick it up and get distracted when she went to bed.

The Benefits of Automaticity

One factor that we’ve mentioned repeatedly is automaticity. Our definition uses the phrase “until it has become almost involuntary.”

Without automaticity—you can do it without really thinking about it—you don’t really have a habit. All those terms (automatic, unconscious, involuntary) are terms we associate with the elephant.

When you are first acquiring a habit, you are relying on willpower to make it happen. If it’s a particularly strenuous habit, you may need to use a lot of willpower, but if you can persist, it becomes easier as it becomes more automatic.

If it becomes automatic enough, it actually becomes easier to do it than to not do it. An example of this is seat belts.

Are you a regular seat belt wearer? If you aren’t you probably should be, right?

But if you are a regular seat belt wearer, what happens when you don’t wear one? For example, have you ever needed to move a car a small distance, maybe to a different parking space, and you don’t wear your seat belt? There’s no danger—you aren’t going to exceed five miles an hour, there are no other cars or obstacles of any kind—but it doesn’t feel right. It’s essentially impossible to be in jeopardy, but it still feels twitchy and uncomfortable to not put your seat belt on.

If you are not a driver, then there may be some other equivalent—say, when you need to get off the bus or train a stop later than usual, or when you deviate from your morning routine.

Whenever you are deciding to act or not act, you are balancing the effort of action against the potential benefit of that action. Putting on your seat belt clearly has benefit, but it’s an infrequent benefit; you might put your seat belt on a thousand times before anything happens that actually necessitates the seat belt. If you had to consciously exert willpower every time you put your seat belt on—if it were essentially the same amount of effort the thousandth time as it was the first time—it would be difficult to keep doing it in the absence of visible benefit, but making it a habit reduces the effort necessary to repeat the action. After putting on your seat belt becomes automatic, the effort to do it is very, very small.

Identifying Habit Gaps

So how do you know the difference between something that is a procedure or a skill and something that is a habit? The answer is that there is probably overlap between those categories, but conscious effort and automaticity are probably the main criteria to look at.

Many habits may not require much skill. My dental hygienist could explain the skill behind flossing, but the subtlety is lost on me. As far as I’m concerned, it’s a procedural task but not much of a skill. So if I’m not flossing regularly, the gap isn’t my ability to floss, but rather because I lack the habit. I need to figure out how make flossing an automatic behavior that doesn’t require a lot of conscious effort.

Identify the Habit

Does it need to be done automatically and without concious effort?

But what if the gap is not so clear-cut? Many behavior gaps could require an overlap of skill development and habit formation.

Overlap

A habit can be based on what was begun as a learned skill.

I had a job in college doing data entry for loan applications. Loan applications have a lot of numbers, and I got pretty used to using the 10-key pad on my keyboard:

Even today, if I need to enter numbers, it’s much more natural for me to use the 10-key pad, and if I’m on a laptop without one, I find it incredibly awkward.

I wouldn’t have acquired that habit without first learning to use a 10-key pad (a skill, requiring practice), but now that skill is also a habit. I automatically use a 10-key pad when it’s available, without really thinking about it or making a conscious decision.

These are both simple, self-contained examples. Let’s take a look at a more complex behavior, and what parts of it are habits. Let’s talk about time management.

Example: Time Management

Everyone agrees that time management is a crucial skill that we need in both our personal and professional lives, but let’s focus on time management for work. Is time management a habit?

In and of itself, time management is too big a set of behaviors to be a habit, but it contains several habits.

Francis Wade, in his book Perfect Time-Based Productivity, identified that time management, rather than being a few small behaviors, is a series of large behaviors (e.g., capturing, emptying, tossing, acting, storing, etc.) that are composed of several smaller behaviors.

He defines capturing as “the process of storing time demands (e.g., tasks or to-do items) in a safe place for later retrieval and processing.” Basically, how do you track all the things you need to do?

Time management is something I struggle with. Some of my to-do items are in my email inbox, some are scribbled on notes stuck to my computer monitor, some are in meeting notes in my notebook, some are in my actual to-do application, and some are (unfortunately) just in my memory.

Some of the habits Wade identified for a better method include:

• Carrying a manual capture point (other than memory) at all times. Basically, this is the habit of always having a way to write down the things you need to do. It could be a notebook, a smartphone app, a voice recorder, or whatever works for you, but the first habit is just making sure you always have it with you.

• Capturing manually. This second habit is actually using your capture device (not just remembering to take it with you). It’s actually writing things down in your notebook or adding things to your smartphone app.

• Consolidating things from automatic capture points. This involves pulling tasks or to-dos from other places (email, text messages, etc.) into your main capture device, rather than having tasks in several different places.

None of these items requires a high degree of skill or a steep learning curve. They are all simple behaviors. But getting them to be a regular part of your time management practice really does require making them automatic habits.

Context and Triggers

The context and triggers for each of these habits are a little different. For example, the context for the first behavior (carrying a manual capture point) is getting ready for work in the morning or getting ready to leave the office.

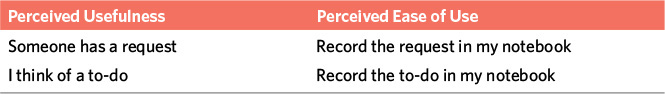

The context for the second behavior (capturing manually) is a little different. The triggers there might be someone asking you to do something, or you thinking of something you want or should do.

This makes the second habit a little more complicated, as the contexts are a little less predictable. To-do items could happen during a meeting, during a hallway conversation, on a phone call, or anywhere you just happen to think of something. Because the triggers can be so much more variable, the ability to recognize the trigger and the need to create an automatic association between the trigger and the behavior become all the more important.

Questions to Ask

Some of the questions you can ask to identify and understand habit gaps are:

• Is this something that people need to do consistently and automatically?

• If I break this behavior down to its smaller components, do habits become visible?

• What is the specific context or trigger that is involved?

• Do those triggers occur at variable or unpredictable times?

• Is this something that isn’t automatically part of a larger process?

• Is there an undesirable habit that needs to be undone first?

Designing for Habit

So what are some of the solutions that can be applied to habit formation? The science is still developing around this question, actually. The healthcare industry, in particular, is looking closely at habit design because dealing with many of the most expensive health conditions relies on consistent healthy (habitual) behaviors. Researchers at Stanford and MIT are trying to decode the behaviors and brain functions behind habit formation.

The software industry is paying attention as well. Habit formation is being studied by software designers who would love for their new app to become a regular part of your day. Apps are also being designed to help you develop your own habits, whether you are trying eat better, manage your inbox, or avoid distractions.

Although the science around habit formation is still forming, some strategies have been identified.

Implementation Intentions

The academic and researcher Peter Gollwitzer spends a lot of time on the idea of implementation intentions. He explains them as follows:

Implementation intentions are if-then plans that connect anticipated critical situations with responses that will be effective in accomplishing one’s goals. Whereas...goals specify what one wants to do/achieve (i.e., “I intend to perform behavior X!”...), implementation intentions specify the behavior that one will perform in the service of goal achievement if the anticipated critical situation is actually encountered (i.e., “If situation Y occurs, then I will initiate goal-directed behavior Z!”).

So if you are trying to quit smoking, you need more than the goal (“I’m going to stop smoking”)—you need the implementation intention of how to actually do it.

If I get a craving, I will distract myself.

You have situation Y (“If I get a craving”) and behavior Z (“I will distract myself”). This is more effective than just the goal (“I will quit smoking”). But you can make it much more effective by being specific:

If I crave a cigarette when I’m stressed out, I will call my sister.

If I crave a cigarette when I’m bored, I’ll play that candy game on my phone.

If I crave a cigarette because it’s after lunch, I will take a 5-minute walk outside.

If I crave a cigarette because I’m in a social situation, I’ll chew gum.

It turns out that deciding how to handle a fraught situation requires a lot of effort, and exerting willpower also requires a lot of effort, according to the psychologist and researcher Roy Baumeister. If you make the decision ahead of time (“If Y happens, I will do Z”), then the action is clear and you have more cognitive resources to apply to taking the action.

As part of a learning experience you can have people identify their own anticipated critical situations, and have a specific behavioral strategy for responding (“When I have problem X with my difficult employee, I will do Y”). Have people create their own implementation intentions and remember that specificity is crucial to success.

Shrink the Habit

If a habit seems overwhelming, make it smaller. Both Chip and Dan Heath (in their excellent book Switch) and BJ Fogg, in his Tiny Habits program, discuss the importance of identifying the smallest productive behavior and focusing on that.

We talked about how making a behavior habitual makes it easier to do, but if the behavior is too effortful to be established as a habit, is there a way you can make it smaller and more manageable?

For example, if you want to develop the habit of regularly getting up and stretching at your desk so that you don’t sit too long, it’s probably best not to start with a full set of yoga poses as you try to build your habit. Instead, could you stand up and reach your arms up once? Or even just stand up? Eventually, if that becomes a habit, you can add more behaviors to the established habit, which is easier than creating a whole new habit. If you are overwhelmed by the big behavior, what’s a small behavior you can do?

Practice and Feedback

The most obvious solutions are in some ways the most challenging: practice and feedback.

As we mentioned when discussing motivation in Chapter 8, the hardest behaviors to acquire are the ones in which there’s no visible feedback.

In Francis Wade’s time management example, he recognized that time management frequently feels intangible. Although you recognize the impact of poor time management overall, the specific behavior is often without immediate consequence. If you forget to write down a task, the impact of that isn’t felt for quite a while, long after the behavior has failed to occur.

To make things more visible, Wade created a level system (using the same belt colors as are used in martial arts) to make time management behaviors more visible. Each behavior has a self-diagnosis rubric to help people identify where they are with their time management habits:

From Francis Wade’s Perfect Time-Based Productivity. Used with permission.

This is the same logic that underlies many of the “quantified self” gadgets—the fitness trackers, food diaries, and habit reminder apps. How can we make behaviors more visible and reinforce practice?

Reduce the Barriers

A key question to ask when thinking about design for habits is, “Is there any way to make the behavior easier?” That is, is there anything you can do to reduce the barriers to performance?

I live in a place where winter goes on for a long time, and it’s hard to get enough sun exposure in the winter months. My doctor recommended a vitamin D supplement, which I was bad at remembering to take.

The way I was finally successful was by chaining the vitamin-taking behavior to an existing behavior that I had no problem with: my morning coffee habit.

I work from home, and one of my first actions most mornings is to make a cup of coffee. This usually involves a few minutes of lingering around the kitchen while the water boils. If I put the vitamin D container next to the coffee jar, it became much easier to remember to take the vitamin. In fact, the empty time waiting for the water to boil meant that taking the vitamin was as close to effortless as possible. This chains the new habit to an existing habit.

Applying To Learning Design

So how do you build any of this into a learning design? A few possibilities include:

• Have learners create implementation intentions. Give learners an opportunity, or even a template, that allows them to create their own implementation intentions (“If x happens, I will do y”).

• Introduce the habit, and allow learners to brainstorm solutions. Present learners with the goal, and allow them to work on how to accomplish it.

• Carve out time for specific habits. If you are trying to develop habits, it can be useful to spread them out over time and then reinforce that. For example, if a healthcare facility wants its staff to develop some new habits, they could introduce one very small habit at the beginning of each month, and have a fun campaign about working on that single habit for the first week of the month, with a few follow-ups later in the month. That way, there’s sufficient time for a habit to develop.

• Reduce the barriers. Identify ways you can reduce the barriers and, even more importantly, give learners the opportunity to think about how they can reduce the barriers for themselves.

• Create rubrics or tracking mechanisms. Figure out what you can do to make the habit more visible.

• Help tie the habit to an existing behavior. Help learners identify an existing behavior they can chain the new habit to.

• Hack the environment. Have learners survey their environment and figure out how they can modify it to support habit development.

• Identify the triggers. Give learners the assignment of observing and noting triggers in their own environment for a few days, and then have them report back. They can practice the activity of looking for triggers before they start adding in the behavior.

One Last Word on Autonomy and Control

In all learning activities, it’s important to give the learner control over their own learning whenever possible, but it’s particularly important for habit development.

It’s worth reiterating that you can’t tell someone a habit. As we all know, habits we want to develop are hard enough. Habits we are reluctantly being coerced into are almost certainly going to fail.

Some habits aren’t optional. Hand-washing for healthcare workers isn’t really optional, but how that habit is best developed can be.

Summary

Summary

• Habits are “an acquired behavior pattern regularly followed until it has become almost involuntary.”

• The difference between weak and strong performance can come down to habits, even when knowledge, skills, and motivation are already present.

• Habit formation requires being able to identify the triggers for that habit, and having a plan in place to respond to those triggers.

• No one can be told a habit. People need to participate in habit formation.

• Habit formation usually requires practice and feedback.

• Hacking the environment, shrinking the habit, and chaining a new habit to an existing behavior can increase the likelihood of the habit being formed.

References

Bandura, Albert. 1977. “Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84: 191-215.

Baumeister, Roy and John Tierney. 2012. Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength. Penguin Books.

Duhigg, Charles. 2014. The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. New York: Random House.

Fogg, BJ. “The Fogg Behavior Model.” Retrieved May 05, 2015, from www.behaviormodel.org.

Habit. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged. Retrieved May 05, 2015, from http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/habit.

Heath, Chip and Dan. 2010. Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard. Crown Business.

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

PSA Texting and Driving, U.K. 2009. www.youtube.com/watch?v=8I54mlK0kVw. Described at www.gwent.police.uk/leadnews.php?a=2172.

Rainforest Alliance, “Follow the Frogs.” www.rainforest-alliance.org.

Rubin, Gretchen. 2015. Better than Before: Mastering the Habits of Our Everyday Lives. New York: Crown Publishers.

Wade, Francis. 2014. “Perfect Time-Based Productivity: A Unique Way to Protect Your Peace of Mind as Time Demands Increase.” Framework Consulting Inc. / 2Time Labs.