8. Design for Motivation

(IN WHICH WE LEARN THAT WE DON’T ALWAYS LEARN THE RIGHT THING WHEN WE LEARN FROM EXPERIENCE, AND THAT THE ELEPHANT IS A CREATURE OF HABIT)

We’ve already spent a lot of time looking at motivation to learn (remember the elephant?), so this chapter concerns itself with what motivates learners to do. Sometimes learners will have the knowledge and skills they need but still won’t actually do the right things. You can’t necessarily fix that as a learning designer, but there are things you can do to help.

Motivation To Do

Numerous studies have come out in the last few years that say texting while driving is a very, very dangerous thing to do.

Shocking.

That texting while driving is dangerous probably isn’t a surprise to the vast majority of the population. So why do people continue to do it? I don’t know exactly, but I suspect it’s because people have one, or a mix, of the following thoughts and responses:

• “I know it’s a bad idea, and I never do it (except when I do, and then I feel guilty).”

• “I know it’s a bad idea, but I only do it once in a while, and I’m very careful.”

• “I know it’s a bad idea for other people, but I can do it because I’m really good at it.”

• “Huh? What’s the big deal?”

Most of the responses above indicate that this is not a knowledge problem, and that an intervention that focuses on knowledge isn’t going to change anything, because it’s not the “know” part but rather the “do” part of the sentence that’s the problem.

So why do people do things they know are a bad idea? It’s not because they aren’t smart people. If it’s not a knowledge problem, then more knowledge probably won’t help.

A big part of this goes back to our elephant and rider. Frequently, the rider knows, but the elephant still does.

We Learn from Experience

Part of the reason for “I know, but...” is that people learn from experience, which is a great thing (we wouldn’t want to live in a world where people didn’t), but it can cause some problems. The elephant in particular can be far more influenced by experience than by abstract knowledge.

Here’s an example. Let’s say that 1 in 10 instances of texting while driving results in an accident (this isn’t a real statistic; I don’t think that exact data is known—this is just for purposes of argument). Let’s take a look at the experience of two different drivers:

Both drivers are learning from experience, but the lesson Driver 2 is learning from experience is that texting while driving is fine—see, look at all the experience that confirms that! Until it isn’t fine, of course.

This is why people have a really hard time with activities where the action is now but the consequence is later. The elephant is a creature of immediacy. Take a look at these classic “I know, but...” activities.

Classic “I know, but...” activities

In these activities, the elephant is being asked to sacrifice in the present for some future gain, but the elephant is only really persuaded by what’s happening now and by the experience of the immediate consequences. The rider knows that there’s an association with the future consequence, but whatever that future consequence is, it’s too abstract to influence the elephant.

Remember, Change is Hard

You might not be trying to fix behaviors as difficult as smoking, but anything that involves extra effort will be a lot easier if the elephant is onboard with the program.

In particular, changing an existing pattern of behavior can require effort for the elephant. The elephant is a creature of habit, which means that if the elephant is used to going left, it’s going to require a fair bit of conscious effort to get it to go right instead.

Before we look at ways to influence learner behavior, let’s be clear about one thing: None of this is about controlling the learner. It’s not about tricking your learners into compliance. Instead, it’s about designing environments that make it easier for those learners to succeed.

The experience they have when they are learning about something can make a difference in the decisions they make later.

Designing for Behavior

So what are strategies we can use to help our learners be more motivated?

The Technology Acceptance Model

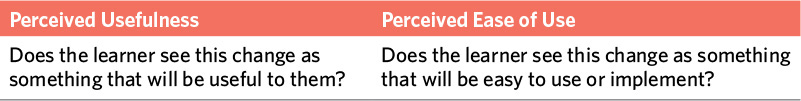

The technology acceptance model (TAM) (Davis 1989) is an information systems model that looks at what variables affect whether someone adopts a new technology. It’s been fairly well researched, and although it isn’t without its critics, I find it to be a useful frame. At the heart of the model are two variables:

It’s not a complicated idea—if you want someone to use something, they need to believe that it’s actually useful and that it won’t be a major pain in the butt to use.

TAM specifically addresses technology adoption, but those variables make sense in a lot of other areas as well.

I keep TAM in mind when I design anything that requires adopting a new technology, system, or practice (which is almost everything I do). Some of the questions I ask are:

• Is the new behavior genuinely useful?

• If it is useful, how will the learner know that?

• Is the new behavior easy to use?

• If it’s not easy to use, is there anything that can be done to help that?

Diffusions of Innovation

The other model I find really useful is from Everett Rogers’s classic book Diffusion of Innovations. If you haven’t read it, you might want to get a copy. It’s a really entertaining read, packed with intriguing case studies and loaded with useful stuff. The part I want to focus on here is his take on what perceived attributes affect whether a user adopts or rejects an innovation:

Relative advantage—The degree to which an innovation is perceived as being better than the idea it supersedes

Compatibility—The degree to which an innovation is perceived to be consistent with the existing values, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters

Complexity—The degree to which an innovation is perceived as difficult to use

Observability—The degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others

Trialability—The opportunity to experiment with the innovation on a limited basis (Rogers 2003)

There is obviously some crossover with TAM, but if I’m designing a learning experience for a new system, I use this as a mental checklist:

![]() Are the learners going to believe the new system is better?

Are the learners going to believe the new system is better?

![]() Are there compatibility issues that need to be addressed?

Are there compatibility issues that need to be addressed?

![]() Can we do anything to reduce complexity?

Can we do anything to reduce complexity?

![]() Do the learners have a chance to see it being used?

Do the learners have a chance to see it being used?

![]() Do the learners have a chance to try it out themselves?

Do the learners have a chance to try it out themselves?

![]() How can learners have the opportunity to have some success with the new system?

How can learners have the opportunity to have some success with the new system?

If somebody really, really doesn’t want to do something, designing instruction around these elements probably isn’t going to change their mind. And if a new system, process, or idea is really sucky or a pain in the ass to implement, then it’s going to fail no matter how many opportunities you give the learner to try it out.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy can be described as someone’s belief in their own ability to succeed. Basically, it’s the little engine that could (“I think I can...I think I can...”).

Earlier in the book, I mentioned a curriculum for drug and alcohol prevention for middle-school students (www.projectalert.com). One of the key elements of that curriculum is developing the students’ sense of resistance self-efficacy.

Which of these guys do you think is more likely to try a new method or procedure?

Dealing with peer pressure involving drugs, cigarettes, and alcohol is another classic “I know, but...” scenario, right? For example, kids don’t start smoking because they don’t know smoking is bad. They’ve all gotten that message, so there are other reasons. But the situations where students need to make the right decision are emotionally fraught, high-stress situations. Being able to act confidently can make a big difference in those situations.

Students participating in the prevention curriculum practice, and practice more, and practice more how they are going to handle the situation. They have statements ready, and they’ve tried them out in role-play scenarios. Additionally, they have the confidence of their peer group in the class, who have also talked about their strategies in the same circumstances.

In addition to feeling capable, it helps if learners also feel that the necessary task or skill is within their control.

Carol Dweck, a social and developmental psychologist and researcher, conducted an experiment with fifth graders (Mueller & Dweck 1998). She had the students solve a set of problems. When they were done, half the group was told “You must be smart at these problems” and the others were told “You must have worked hard at these problems.” She then had students attempt subsequent tasks.

Dweck describes the results:

We found that praise for intelligence tended to put students in a fixed mind-set (intelligence is fixed, and you have it), whereas praise for effort tended to put them in a growth mind-set (you’re developing these skills because you’re working hard). We then offered students a chance to work on either a challenging task that they could learn from or an easy one that ensured error-free performance. Most of those praised for intelligence wanted the easy task, whereas most of those praised for effort wanted the challenging task and the opportunity to learn.

When the students tackled subsequent tasks, the students who had been praised for intelligence (something not in their control) did worse than they had done initially, and the students who had been praised for working hard (something they did control) did better overall.

Well, that seems to have worked pretty effectively with kids, but are there ways to improve the self-efficacy of adult learners as well?

When fear, anxiety, or discomfort with the new behavior has been identified as one of the main issues, practice becomes particularly important.

In the handwashing example, we identified talking to another colleague about their lack of hand hygiene as a problematic behavior. Nobody really wants to have that awkward conversation with a colleague.

It’s likely that the only way a health care professional would get past the discomfort of that conversation is through practice. Just like the kids in the Project ALERT classes who had to practice how they were going handle an offer of cigarettes or alcohol, health care staff probably need to practice how they will gently remind a colleague that they might want to use some hand gel before examining a patient.

Modeling and Practice

In Marianna’s example, we looked at the value of observing someone else and of practicing to develop self-efficacy.

These practices have benefits besides developing self-efficacy. We know that the elephant is a creature of habit, and that it likes to learn from its direct experience (remember the second driver in the texting example?).

It takes effort to switch paths. By creating opportunities for the learner to see behaviors modeled and to practice them, you greatly increase the likelihood that those behaviors will continue later.

Another way to practice and to increase the likelihood of a behavior being used is to walk learners a few steps down the path as part of the learning design. By this I mean to have your learners prepare themselves to employ the knowledge or skill by actively figuring out how they will use it to address their own specific challenges or tasks—stick with them as they think through moving from the theoretical to the practical.

We’ve talked a lot about using scenarios to make learning more vivid and engaging, but the best scenarios are the learner’s actual problems or challenges.

Here are some examples:

This set of tactics does a few useful things. First, it gets the learners imagining how they can use the material in their own world. They start picturing the possibilities and figuring out how to deal with obstacles.

Second, it lets the learner get some practice with their own material when there is still support to iron out snags.

Third, the learners have now made an investment. Behavioral economists talk about sunk cost and loss aversion. People have a strong reluctance to discard something that they’ve already invested in.

Fourth, they are ready to go when they get back to the real world. There’s always a barrier to starting something new, and if the learner has already scaled part of that barrier, then there’s less effort required from them as they continue.

So whenever it’s feasible, have learners apply the subject matter to their own situations.

Social Proof

We’ve already talked about how a good way to attract an elephant’s attention is to tell it that all the other elephants are doing it.

But social proof (as discussed in Chapter 5—you remember, the tendency of people to base their own actions on the actions of others around them) is not only useful for attracting attention. It’s also really good for encouraging the behavior.

Additionally, we can’t be experts on everything, so a good tool—often an effective shortcut—is to turn to or cite people whose opinions we respect and whose advice we seek. If those people tell us that something is useful, we are much more likely to try it ourselves. I have folks who, if they tell me to go check something out, I’ll do it without much question because I trust their opinion.

I’ve worked on a number of client projects where, at the beginning of the course, there has been a “this is a really important initiative” message from the CEO or the relevant vice president, which is fine. It’s good to know that a project is known and supported at the top—it gives it a feeling of authority, I guess you’d say.

But really, who is, or should be, the actual authority figure when it comes to doing your job? Is it the CEO, or is it the person in the next cubicle who has five times as much experience as you? If you are shopping on Amazon, whose opinion are you going to really value—the publisher, whose blurb assures you this author is a GENIUS, or the 19 readers who said “meh”?

In the Project ALERT drug-prevention project, they use influential opinion leaders to talk to kids about reasons not to do drugs. Granted, the term “influential opinion leaders” means different things in different situations, but if you are a 13-year-old school kid, whose opinion would you most value?

Obviously, that depends on the 13-year-old, but as a general rule, for middle schoolers, high school kids are pretty much the arbiters of what is and is not cool. To that end, Project ALERT doesn’t spend a lot of time on lectures from adult authority figures, but they make good use of teenagers talking about their experiences and about how to make good choices.

So think about it—given your subject matter, who are the really influential people in your organization or in the eyes of your target audience? How can you make those opinions visible? Here are a few possibilities:

• Have people describe successes with the process, procedure, or skill. These descriptions can be presented on an intranet, on a discussion forum, in email blasts, or through any delivery methods already available in an organization. If possible, you could create mini feature stories about the person who is using the process to good effect—that person could be the star of the show.

• Engage opinion leaders first. Involve your opinion leaders in the planning of the endeavor and in the creation and design of the learning experience. Can you have them lend case studies, or agree to champion the undertaking? Can you have them mentor others?

• Make progress visible. Many games put up leaderboards to show who is really killing it. While shaming low-performing people publicly is counter-productive, having a way to acknowledge those who are succeeding can encourage others.

Visceral Matters

The elephant is not influenced only by outside forces like peer encouragement. The elephant is also swayed by direct experience and strong emotion. Direct visual choices and visceral experiences can sway the choices that learners make.

For example, in the cake-or-fruit-salad choice from Chapter 5, people were more likely to pick the cake if it was actually in front of them. When the choice was more abstract, they had more self-control about choosing fruit salad.

Thinking back to our texting-while-driving issue, how could we make the experience more visceral or direct for people?

Here are a couple of ways this has been done:

• The New York Times created an interactive game that tests how good you are at changing lanes while distracted by a text message. It measures how much your reaction time slows down when you are trying to deal with distractions. You get direct experience with your own limitations. Unfortunately, it’s not a very realistic simulation (you change lanes by pressing numbers on the keyboard).

• In 2009, the Gwent police force, in Wales, sponsored the creation of a video showing teenage girls in a car. The driver is texting, and while she does, the car drifts across the median line and strikes an oncoming car. A horrific accident ensues, and you see every graphic detail.

These are both visceral procedures—one involving direct experience and one an emotionally wrenching video. There’s no data I can find on the outcome of either solution, unfortunately. However, I can tell you from experience that I do flash on the memory of the video if I’m ever tempted to break my own rule against texting while driving.

While scare tactics often fail to change behavior, there does seem to be some benefit to strong visceral experiences, although more research is needed in this area.

You Need to Follow Up

All of the above suggestions and strategies can be useful, but possibly the most important idea to keep in mind is this:

Change is a Process, Not an Event

Any time you want learners to change their behavior, it’s a process and it needs to be reinforced.

The ways to reinforce the change are all the things we’ve already discussed, so this isn’t a new idea at this point, but it’s still an important point. Be patient! Even if all your learners start out with the best intentions and are making a conscious effort to implement the new solution or innovation, they are likely to trickle off if the change isn’t reinforced. Always consider how that change will be reinforced over the long term.

Summary

Summary

• There are two kinds of motivation that learning designers need to consider: motivation to learn and motivation to do.

• When you hear “I know, but...,” that’s a clue that you’ll probably need to design for motivation.

• “I know, but...” frequently comes up when there is a delayed reward or consequence.

• We learn from experience, but it can be a problem if we learn the wrong thing from experience.

• Lack of visible feedback or consequences is one of the most common attributes of a motivation challenge.

• We are creatures of habit—irritating for the short-term learning curve but potentially useful if we can help learners develop a new habit.

• You may be able to influence your learners, but you can’t control them.

• Learning designs should show the learners how something new is useful and easy to use.

• Try to ensure that your learners get the opportunity to observe and try new processes or procedures.

• Learners need to feel a sense of self-efficacy with the new challenge or skill.

• Learners may need to practice uncomfortable or difficult behaviors until they can overcome anxiety and feel confident.

• Use opinion leaders as examples.

• Visceral experiences may have more impact than abstract ones, although the research on this topic is ongoing.

• Change is a process, not an event.

References

Bandura, Albert. 1977. “Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84: 191–215.

Dance, Gabriel, Tom Jackson, and Aron Pilhofer. 2009. “Gauging Your Distraction.” New York Times. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2009/07/19/technology/20090719-driving-game.html.

Davis, F. D. 1989. “Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology.” MIS Quarterly 13(3): 319–340.

Dweck, Carol S. 2007. “The Perils and Promises of Praise.” Educational Leadership 65 (2): 34–39.

Fogg, BJ. 2011, 2010. Behavior Model (www.behaviormodel.org) and Behavior Grid (www.behaviorgrid.org).

Mueller, Claudia M. and Carol S. Dweck. 1998. “Intelligence Praise Can Undermine Motivation and Performance.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75: 33–52.

PSA Texting and Driving, U.K. 2009. www.youtube.com/watch?v=8I54mlK0kVw. Described at www.gwent.police.uk/leadnews.php?a=2172.

Rogers, Everett M. 2003. Diffusion of Innovations (5th edition). Glencoe: Free Press.