“The Web is more a social creation than a technical one. I designed it for a social effect—to help people work together—and not as a technical toy. The ultimate goal of the Web is to support and improve our weblike existence in the world. We clump into families, associations, and companies. We develop trust across the miles and distrust around the corner. What we believe, endorse, agree with, and depend on is representable and, increasingly, represented on the Web. We all have to ensure that the society we build with the Web is of the sort we intend.” | ||

| --TIM BERNERS-LEE, WEAVING THE WEB[1] | ||

If you’ve ever watched someone shop at Amazon.com, you may have witnessed the Amazon Effect.

I first saw the Amazon Effect during a usability study several years ago. I was observing a person shopping for a digital camera recommended to her by a friend. As part of the testing procedure, I asked the shopper to go to CircuitCity.com and try to buy the camera. She started typing the URL, then stopped.

<dialog> <speaker>Shopper:</speaker>Can I go to Amazon first?

<speaker>Me:</speaker>No.

<speaker>Shopper (frowning):</speaker>Well, I always go to Amazon first. I love Amazon.

</dialog>Unfortunately, our testing methodology didn’t allow for that. We couldn’t let people shop just anywhere. We were testing very specific sites at the request of our client. Though we were testing Amazon in the study, we weren’t testing Amazon with this particular shopper.

Me: I’m sorry. I can’t let you go there just now. But let me ask: why do you want to go to Amazon?

Up to that point, we’d had a couple of people ask to visit Amazon in the test and had assumed they kept asking because they had accounts there. We figured they had previously shopped at Amazon and had a history with the company, had created wish lists and purchase histories there, and were generally more comfortable shopping in a familiar environment. We assumed the familiarity of Amazon was what kept them coming back.

But as with so many assumptions, it was wrong.

<dialog> <speaker>Shopper:</speaker>I go to Amazon to do research on a product I’m shopping for, even when I plan to buy it on another site.

<speaker>Me:</speaker>Even when you plan to buy it on another site?

<speaker>Shopper:</speaker>Yes, of course.

</dialog>Wow! This wasn’t what we had expected. People wanted to go to Amazon so badly to do product research, not because they had an account there. The magnetic pull of Amazon, what I like to call the Amazon Effect, was entirely different from what we had assumed.

So why the pull of Amazon versus, say, another online electronics retailer? Didn’t Amazon have the same information as other sites? Weren’t they basically all selling the same cameras? What does Amazon do that others don’t?

The answer becomes clear almost immediately when watching someone shopping: customer reviews.

At Amazon, customer reviews act like a magnet, pulling people down the page. That’s the content people want. The page loads, the viewer starts to scroll. They keep scrolling until they hit the reviews, which in some cases are up to 6000 pixels down from the top of the page! Nobody seems to mind. They simply scroll through screens and screens of content until they find what they’re looking for.

During a test a few days later, another shopper exhibited a distinctive behavior. He went to the reviews and immediately sorted them to bring the 1-star reviews to the top of the list. This meant they wanted to see the negative reviews first.

<dialog> <speaker>Me:</speaker>Why did you do that?

<speaker>Shopper:</speaker>Well, I want to make sure I’m not buying a lemon.

</dialog>Another shopper, who exhibited the same behavior of going directly for the reviews, told me why they rarely look at the other content on the page—the wealth of content like the manufacturer’s description and other product information.

Shopper: I already know what it’s going to say, it’s going to tell me how great their product is. Why would I need to read that? If I want to know the truth, I have to read what other people like me thought about it.

There it was: a crystallization of the value of customer reviews. Customer reviews allow people to learn about a product from the experience of others without any potentially biased seller information. No wonder everyone wanted to shop at Amazon. They had information that no other site had: they had the Truth.

And that truth, interestingly enough, arose from simply aggregating the conversation of normal people like you and me.

Let’s take a bird’s-eye view of what’s happening at Amazon. Consider these peculiarities:

Amazon doesn’t always provide the most valuable information on their site. Instead, the people writing reviews contribute valuable information others are looking for. Amazon simply provides the tool with which to write the reviews.

People write reviews without getting paid. There is no monetary reward for writing reviews. Yet dozens of reviewers have written over a thousand reviews each! These folks know they aren’t going to get paid, but do it anyway.

People are not being managed in any tangible way. This incredible outpouring of reviews is not being managed. Individuals are acting independently of one another and together provide an amazing resource.

People pay attention to strangers they’ll never meet. Yet, they still take the time to help out these strangers by describing their experience with a product.

People police each other. In addition to taking the time to write reviews, people also help judge whether they found a given review helpful, thereby weeding out the bad (by pushing them to the bottom).

People openly identify themselves. Even in this most public of places, where anybody could see what they’re doing, most people freely identify themselves.

Given our common conception of how to get people to do work, many of these points are counter-intuitive. We’ve been taught that hard work is rewarded by an honest wage, yet people at Amazon are working for free. People aren’t supposed to work for free. The value of customer reviews flies in the face of how economics is supposed to work!

The models that economists have created assume there must be an incentive for production, in plain terms money. So how could Amazon create such a large, stable, valuable system without paying any of their contributors even a penny for their efforts?

The conclusion we must reach is staring us in the face:

Amazon’s reviews are about much more than money.

Indeed, the overwhelming success of Amazon’s reviews is evidence of a way in which the web has produced a dramatic change in the world’s economy. In traditional economic terms the mere existence of reviews just doesn’t compute. Few existing economic models can accurately describe the value being given (or received) on Amazon.

Yochai Benkler, author of Wealth of Networks, a wonderful book describing these new economic changes in detail, notes:

A new model of production has taken root; one that should not be there, at least according to our most widely held beliefs about economic behavior.

It should not, the intuitions of the late-twentieth-century American would say, be the case that thousands of volunteers will come together to collaborate...

It certainly should not be that these volunteers will beat the largest and best-financed business enterprises in the world at their own game.

And yet, this is precisely what is happening...[2]

Of course Amazon isn’t the only one designing for and supporting the activity of its audience in this way: it is merely one of countless examples of social design on the web. For the purposes of this book, we define social design in the following way:

Definition

Social design is the conception, planning, and production of web sites and applications that support social interaction

We’ve barely seen the tip of the iceberg when it comes to designing social software. I’m confident we’ll be discussing social software (and how to design it) for decades to come. It is the future of the web. Here are several reasons why:

Humans are innately social. Since humans are social, it makes sense that our software will be social, too.

Social software is a forced move. The sheer amount of information and choice we’re faced with forces us toward authentic conversations (and tools to help us find and have them).

Social software is accelerating. Social software is trending upward: it is already the fastest growing and most widely used software on the web. The future suggests more of the same.

Let’s take a look at each of these reasons in depth to get a clearer picture of the rise of the social web.

Humans are innately social creatures. We exhibit social behavior. If we did not, if we weren’t social from the day we are born, then social software would be incongruous: it just wouldn’t make sense. Instead of garnering our attention and energy, Amazon, eBay, and MySpace would be worthless.

While most of us would agree that we are social by nature, what exactly does it mean to be social? Well, social is a fuzzy term, and most dictionaries define it as something to do with “group formation” or “living together.”[3] But those terms don’t illustrate the richness of our social lives. Being social is more than merely forming groups: it’s all the interactions, decisions, and conversations that happen in and around those groups!

It includes, but certainly isn’t limited to:

Sharing, caring, feeding, loving, fighting, conversing, friendship, sex, envy, shouting, arguing, betrayal, rumor mongering, gossiping, laughing, crying, providing support, whining, advocating for others, recommending, swearing off.

The mere fact that we as humans organize ourselves into groups isn’t all that special. After all, other animals form groups. But as this list shows, being in groups, and being around groups, and not being in groups really changes the way we behave.

We didn’t always think this way. In 1933, German behavioral psychologist Kurt Lewin, escaping Hitler’s rise to power, emigrated to America in order to continue his studies on group behavior. At that time, the commonly held notion about human behavior was that we act according to our personality. Sigmund Freud and his theories on the unconscious mind were in vogue. Most of the prevailing research assumed in one way or another that our inborn tendencies dictated our behavior.

But Lewin’s research said different. He challenged the prevailing wisdom by formulating a simple yet profound statement to describe human behavior. The statement, which was expressed as an equation, of all things, thrust Lewin to the forefront of an emerging field. Indeed, Lewin is often called “the father of social psychology.”

This is Lewin’s equation:

B = ƒ(P,E)

The equation says that an individual’s behavior is a function of both their personality and their environment. While the classic nature vs. nurture debate asks you to take sides, Lewin’s equation does not: it invitingly allows for both the person and their environment to affect what happens in a complex, yet profound, way.

Lewin’s equation highlights the tension between the individual and the environment. The environment, of course, is basically made up of everything that isn’t us. That’s an awfully big set of things to think about! However, we easily recognize several types of environments. One is the physical environment, which has a tremendous effect on what we do. When it’s cold outside, we must put clothes on or suffer the consequences.

Other people and groups make up our social environment. And, perhaps even as much as the weather dictates how we dress, the actions of others affect how we behave. Imagine how many of our decisions are strongly influenced by what other people say or do. Just as the friend who made a product recommendation to our shopper on Amazon influenced her behavior, so we are profoundly influenced by the people we know and the groups we join.

In the software world there is even another kind of environment: the software interface.

The interface is the environment in which people work and play on the web. It is the arbiter of all the communication and interaction that takes place there. If there is an action available in an interface, then you can perform the action. If an action is not available in an interface, then you’re out of luck. While we are intuitively aware of this, just as we are aware of the weather, we rarely reflect on how much our behavior is determined by the interfaces we use. Almost all of it!

This sounds like the designers of the interface are in control! Not so fast. Designing an interface that evokes the desired behavior is a huge challenge.

If the interface is too confining, people won’t use it.

If the interface is too flexible, people won’t know how to use it.

In the middle, the sweet spot, interface designers can create powerful social software that supports the person and their personality, as well as the social environment and the groups they are a part of.

Thus the challenge of social software is to design interfaces that support the current and desired social behavior of the people who use them.

Designing an effective interface has always been tough, even when we were merely designing interfaces for one person to interact with content we controlled. But when we add the social aspect, things get even more difficult. Though we can see glimpses, we have little understanding of the overall effect of social software going forward. In 1985, Howard Rheingold, writing about the nascent personal computer revolution, foresaw social software’s massive challenge and potential for change:

Nobody knows whether this will turn out to be the best or the worst thing the human race has done for itself, because the outcome of this empowerment will depend in large part on how we react to it and what we choose to do with it. The human mind is not going to be replaced by a machine, at least not in the foreseeable future, but there is little doubt that the worldwide availability of fantasy amplifiers, intellectual toolkits, and interactive electronic communities will change the way people think, learn, and communicate.[4]

Just as humans are social, so our software must be as well.

The person shopping at Amazon in the opening of this chapter was relying on social connections to help her make a shopping decision.

She did this in two ways:

First, she asked a friend to recommend a digital camera. That friend, knowing her and her lifestyle, would recommend a camera based on his knowledge of her. Maybe the friend recommended a camera he had experience with. Or, perhaps a different model based on some difference he recognized between them.

Second, the person relied on an informal social network of people at Amazon who wrote reviews. She didn’t know these people, yet she relied on them anyway, trusting them to deliver quality information. The trust in this case is present not because they are friends, as was true for the original recommendation, but because they represent the shared experience of shopping for a camera.

This study was merely the first time this phenomenon became clear to me. Since then, I have noted it in nearly all aspects of life. Voting, shopping, eating, reading, computing, driving... in these and all activities we ask others for help in making decisions. Relying on social networks is how the vast majority of decisions are made!

This reliance on our social network is increasingly a forced move. Living in the Information Age, for all its benefits and wonders, is like drinking from a fire-hose. We have more information than we know what to do with, more than we could ever digest, and probably more than we can even imagine.

And a previous age, the Industrial Age, still has a strong effect as well. The ease of manufacturing at a large scale has caused a situation where we simply have far too many things to choose from. So now we not only have too much information, we have too many products as well. Often we don’t have two or three options to choose from: we have dozens. And then there is a seemingly infinite amount of information about those products! There is simply not enough time to consider each option thoroughly.

To fight this deluge of information, we’re turning more and more to trusted sources, whether they be in our own household or in other social circles. Instead of trying to sort, filter, and weed through endless sources of information, we’re focusing our attention on those we already trust, or those we have reason to believe might be trusted. We don’t have much choice.

Barry Schwartz notes an interesting side effect of this problem: the Paradox of Choice.[5] He has found that when faced with such an overload we not only fail to make the right choice in many situations, but we often actually get paralyzed and make no choice at all! I remember a friend of mine was shopping for a digital camera several years ago, and decided to utilize several online price trackers to help him find the best model at the best price. He became paralyzed by the options. The paradox was realized: he ended up not getting a camera! He had to rationalize this by citing another reason (a change in financial situation) because on the surface, like any paradox, not choosing due to too much information seems irrational. It’s not. It’s human.

The problem with advertisements isn’t just that they’re distracting, it’s that they’re also biased: they don’t represent a truthful view of the world. They’re all about sell, sell, sell. When we see an advertisement, we’re seeing an idealistic vision of the world that simply doesn’t exist.

As the shopper on Amazon said in reference to the camera manufacturer: “I already know what they’re going to say.” This bias is simply unacceptable. To retain our sanity in a world of too many biased messages, we’re being forced to rely on our social circles to give us sorely needed unbiased perspective. We’ll go out of our way for an authentic conversation with someone we can trust. We don’t want to know how excited someone is to tell us about their great new thing, we want to hear what people like us have to say. Just like the Amazon shopper.

Combine the increased number of items to choose from, the blitz of advertising, and the explosive growth of the web, and it’s easy to see why we are swimming in information. Humans have never had to deal with such a situation.

In 1971, seeing the writing on the wall (and everywhere else), the insightful Herbert Simon described the inevitable outcome of this information onslaught:

In an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it[8]

Simon points to the real need here: we need to allocate our attention efficiently. In other words, we need to pay attention to what matters, and try to ignore what doesn’t.

The Attention Economy, as it has come to be called, is all about the exchange of attention in a world where it is increasingly scarce. Much of what we do on the web is about this exchange of attention. To circle back to the reviews at Amazon, it is definitely about more than money: it’s about attention.

At its very core, social software is about connecting people virtually who already have relationships in the physical world. That’s why MySpace and Facebook are so popular. What do most people do on those sites when they sign up? They immediately connect with friends they already have![9] Or, to put it another way, they maintain their current attention streams. These applications are helping people manage their attention in an economy where it is increasingly hard to do so.

When we join social network sites and focus our attention mostly on the people we know there or give our attention to people like us on Amazon, we’re filtering information and being parsimonious with our most precious asset. We’re effectively saying “No” to the vast majority of information out there, and we’re being forced to do this by the sheer amount of information we face.

Social software has always been successful. Email, which dates from the early 1960s and is arguably the most successful software ever, was actually used to help build the Internet.[10] Email is social, as it allows you to send messages to one or more people at a time. In the late 1970s, Ward Christensen invented the first public bulletin board system (BBS), which allowed people to post messages that others could read and respond to. One BBS, the WELL, gained tremendous popularity in the late 1980s and early 1990s as a well-known online community. Much of the early social psychology research done on online properties was focused on the WELL. Usenet, a system similar to BBSs, also found tremendous popularity in the 1980s as people posted articles and news to categories (called newsgroups). All of these social technologies predate the World Wide Web, which was invented by Sir Tim Berners-Lee in 1989.[11]

The web is incomparable. Now, nearly two decades after its invention, the world has completely and permanently changed. It’s hard to imagine what life must have been like before we had web sites and applications.

Starting with the social software precursors mentioned above, the web has evolved toward more mature social software. What follows is a very abridged history of the web from a social software point of view. This is important because our audiences, except the youngest ones, have lived through and experienced this history and it shapes their expectations.

In 1995, back when Amazon was just a fledgling start-up, the web was quite a different place than it is now. It had just turned five years old. By one estimate it contained 18,000 web sites, total.[12] (Now there are hundreds of millions.) Most of those 18,000 web sites shared a common property: they were read-only. In other words, all you could do was read them. It was a one-way conversation. The information flowed from the person/organization who ran the site to the person viewing it. Sure, you could click on a link and be shown another page, but that was the extent of the interaction. Click, read, click, read. If you were lucky, the site might have listed a phone number that you could call.

That’s not to say that people didn’t use it socially. One person would write something on their web page, and a while later another would respond on their own web page. This made the conversation difficult, but possible. It’s kind of like only being able to talk at your own house. When you want to say something, you and your friend go to your house. To get your friend’s reply, you go to theirs.

Amazon and other pioneers then made a big leap forward: they figured out how to attach a database to the web site so they could store information in addition to simply displaying it. This capability, combined with cookies to save state information, as well as forms for inputting information, turned web sites into web applications. They were no longer read-only. They were read/write. Thus two-way conversation emerged on the web, a conversation between the person using the site and the person/organization who ran it.

Next, as web applications became more sophisticated, designers tried new feature sets. As people got comfortable interacting with them, and as bandwidth increased and access became more pervasive, designers started to enable many-to-many conversations. Feature sets evolved based on which features survived in the new enviroment. Instead of just talking to the people who published a site, you could talk to all the other people who visited it as well.

As the power and reach of the web became evident in the last part of the 1990s, designers started to refashion bulletin board systems for the web, taking advantage of the knowledge gained from those earlier attempts. One casualty of this porting was that the original BBSs largely faded away.

These many-to-many conversations were a small step technologically but a huge step socially. When you go from talking to one party (the site owner) to talking to many parties (other visitors) you enable, for the first time, group interaction. Group interaction is what separates a web application from a social web application.

Another recent step that has brought this change into clearer focus is egocentric software. The rise of social network sites like Friendster, MySpace, and Facebook has put the person at the center of the software. While there has always been talk about community on the web, web software makes a much deeper set of social interactions available to us. You can friend people. You can follow them. You can even send people a kiss.

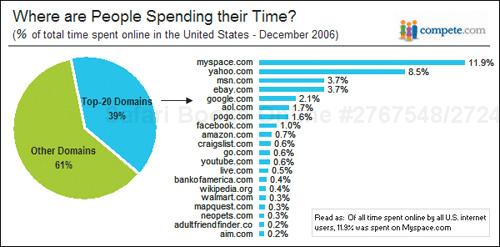

Social web applications are now everywhere. Consider the following list of names you know and love, all of which are in the top 30 most-trafficked web properties in the U.S.:[13]

YouTube grew faster than any web app in history as millions of people uploaded homemade videos

Wikipedia is a collaborative encyclopedia written by tens of thousands of contributors around the world

MySpace is by far the most visited social network property, with 65 million people a month visiting in December 2007[14]

eBay is an amazing ecosystem where perfect strangers exchange billions of dollars a year in auctions without meeting face-to-face

The photo sharing site Flickr allows millions of people to share photos with friends and loved ones

Craigslist provides a simple interface where people can interact easily and do things, such as post classifieds, that they used to do in newspapers

Facebook started on the Harvard campus by emulating an actual book handed out to freshmen (The Facebook) and grew into a behemoth of social networking

IMDb aggregates the movie ratings of thousands of people to provide a helpful answer to the question, should I see this movie?

Thousands of people on Digg, a social news site, submit and rate stories in an attempt to make it to the home page

Google Search works by placing relevance on the collective linking behavior of the entire population on the web

Yahoo’s web-based Mail application is used by hundreds of millions of people

But those are just the biggest ones. Lots and lots of smaller social web applications are sprouting up as people get more comfortable with the idea of interacting socially. Here are some interesting ones:

Sermo. A social network site that connects professional doctors in order to speed up information sharing and dissemination

PatientsLikeMe. A social network site that provides support for people living with HIV, ALS, and others

Kiva. A social network site that lets people in developed countries loan money to entrepreneurs in the developing world

Nike+. An app for runners who can upload their personal exercise information and share with others

LibraryThing. An app that allows you to upload and share your personal library and book ratings with others

RateMyProfessors. A hilarious site that allows students to rate professors in a public forum for all to see

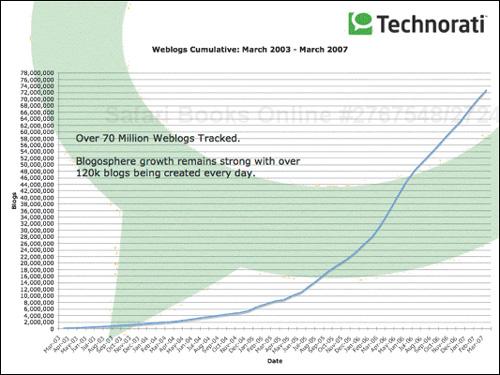

Social web applications are the fastest growing properties on the web. It’s no wonder. Good social sites have social features that enable them to be shared easily. Their entire purpose is to connect people, and when they do that efficiently, they grow very quickly as a result.

YouTube, for example, streams over 100 million videos per day. One of its co-founders, Jawed Karim, notes very few people dispute that YouTube is the fastest growing web site in Internet history.[15]

Here’s an amazing statistic:

In August 2007, over ten percent of the time Americans spent online was on a single social web app: MySpace.com.

With all the choices we have for where to spend our time, nearly twelve percent of all people’s time is spent on a single site! In addition, a mere twenty web domains account for thirty-nine percent of our time online. Many of them are social web applications.

These numbers are startling for several reasons.

We are deeply attached. The average time per visit on MySpace is the length of a sitcom: twenty-six minutes.[16] And, since many people visit MySpace, Facebook, and other social network sites at least once per day, this lengthy stay is habitual. In other words, the social web is becoming a way of life.

We follow our friends. One of the more egalitarian promises of the web is that “every web site is equal.” Any given site has just as much opportunity as the next one. But these numbers show that while this may be true in principle, in practice people strongly congregate where their social circles and their friends are.

In addition to the big name sites above, there are an estimated 100 million blogs on the web. According to the blog-tracking site Technorati, in March 2007 there were approximately 70 million blogs, with 120,000 blogs being added every day![17] By the time this book is published, the number of blogs on the web will be over 100 million.

The growth of the social web is mind-boggling. Even more remarkable, however, is that this growth is unlikely to slow down anytime soon. According to InternetWorldStats, which aggregates statistics from sources like Nielsen/NetRatings:

Only 1.2 of the 6.5 billion people on Earth use the Internet. That’s less than 20%.[18]

Despite the rich history of social software and the rich interactions happening already on sites like Amazon, we are still only at the beginning of the social web. As more and more people from around the world get access to the Internet and grow comfortable interacting socially online, we’ll see a continued growth and maturation of social web applications. The successes of the moment (the Amazons, MySpaces, and Facebooks) will grow and change, and new applications will come to join them or take their place. That kids tend to intuitively grasp and embrace the social nature of the experience is a strong predictor of this future.

[2] Yochai Benkler, The Wealth of Networks. Yale University Press, 2006.

[3] For example, the dictionary on my Mac says: “of or relating to the aggregate of people living together in a more or less ordered community” (this is not very helpful).

[4] Howard Rheingold’s books are wonderful: Tools for Thought (http://www.rheingold.com/texts/tft/) and Virtual Communities (http://www.rheingold.com/vc/book/). Though they were written in 1985 and 1993, respectively, they were at least a decade ahead of their time. Probably two.

[5] Barry Schwartz, The Paradox of Choice. Harper Perennial, 2005.

[6] There is considerable debate about how many ads people see per day, with the key issue being how many we notice vs. how many come into our peripheral vision. See more: http://answers.google.com/answers/threadview?id=56750

[9] For more insight into the reasons why people use MySpace, read Danah Boyd’s: Identity Production in a Networked Culture: Why Youth Heart MySpace http://www.danah.org/papers/AAAS2006.html

[11] Super cool link: Tim Berners-Lee announcing the World Wide Web on Usenet: http://groups.google.com/group/alt.hypertext/msg/395f282a67a1916c

[13] According to Alexa, a useful tool for finding trends (but like all traffic measurement sites, any specific numbers from the site should be taken with a grain of salt).