Chapter 5. Sound and Brand

A SONIC TRADEMARK IS a relatively short piece of audio that does for your sound brand what a visual trademark does for your visual identity: it serves as a single, memorable reference point that gives customers something to grab onto when thinking about your product or brand. For dipping your foot into these audio logos, few places are better to start than by watching Wired’s video, “The Psychology Behind the World’s Most Recognizable Sounds.”1 Here, sound designers explain the effect of some of the most familiar digital sounds on us, including startup sounds, ringtones, and audio logos.

The boink-spoosh of Skype starting up is a good example. It is probably the first thing you think of when asked what Skype “sounds” like, but Skype also makes lots of other sounds that reflect a similarly playful mood. Further, part of Skype’s “sound” comes from the technical methods it uses to compress human voice.

But note that a sound trademark is a subset of the auditory brand experience, not its entirety. Take the Macintosh, for example: the rich, warm chord it plays upon startup might be the most memorable part of its sound experience, but there is also the fan sound, the sound of the mouse and keyboard, and the sound quality that is shaped by the particular speakers hardwired into the machine. All of these elements come together to create a unique soundscape that aligns with the visual and interactive components of the brand.

Whether or not you attempt to design the sound in your product to fit its brand, the sound will be there—even if your product contains no electronics whatsoever. Some brands have sounds that are based on the shape of their packaging or the product itself. The snap, crackle, pop of Kellogg’s Rice Krispies is so iconic that it has become part of the product’s branding. In Germany, a crucial part of the brand identity of Flensburger Pilsener beer is the characteristic plopp! sound that its unique bottles make when opened. Even an ordinary wooden cabinet makes a sound when struck or moved, and this becomes a part of its identity.

Think of an old piece of furniture in your house: their sonic signatures are part of the memories you form about them. As we’ve covered in previous chapters, environments also present many (usually overlooked) opportunities for sound to be added, shaped, or removed, and this can support a brand identity over longer periods of time.

When we get to products that actively produce sound, like apps and smart devices, the potential sources proliferate dramatically. So, it’s worth starting out by cataloging, in very broad terms, the sources of sound that ultimately influence a customer’s experience of whatever you’re designing.

For physical and digital products, this includes:

- Passive elements, such as product enclosures, which both shape the sounds within them and communicate many qualities about the product when touched, tapped, or knocked

- The electronics that make or modify sounds, such as voice chat applications

- Mechanical and electromechanical components such as cooling fans, doorbells, electronic locks, or anything with a motor, switch, or servo in it

For environments, this includes:

- The electronics that make or modify sounds, such as public address systems or background music

- Mechanical and electromechanical systems, such as heating and cooling systems, transformers, or keycard door locks

- Passive elements, such as wind chimes or floor surfaces (when walked upon), but especially architectural acoustics, which contribute tremendously to the identity of a space

Finally, does your product have an essence? Some things have a face, others a voice, and a lucky few have an essence: something that emerges when all the sensory information we gather about a product is coherent. When the experiential touchpoints—context, look, feel, sound, heft, scale, and so forth—fit together well, a product is more likely to have an identifiable individual character.

Every aspect of your brand should feel like it came from the same place, and this includes sound. Many audio branding efforts fail for the simple reason that too much emphasis is placed on the sound trademark or “logo,” and not enough on creating a balanced multisensory brand experience.

As competitors release products into the marketplace, the task of creating a distinctive identity becomes more difficult. Sound is a crucially overlooked tool in this task.

Anything that produces sound is part of your brand. That includes keystrokes on a computer keyboard, the acoustics of tapping on the device itself, the internal components in the motor, and what it sounds like to drop it, eat it, open it, unwrap it, or use it.

If your aim is to use sound to improve the experience of using the product in a way that reinforces existing brand characteristics, then your strategy should start with sensitivity and empathy toward your customers’ needs and expectations.

Types of Trademarks

A sound trademark will contain at least one or more of the following features:

- Rhythmic structure: a “beat” or identifiable rhythmic pattern

- Unique tone color (timbre)

- A melody or motif; this is by far the most popular implementation

- A chord or series of chords producing harmony

- A spoken voice or series of words

Rhythm-Based Trademarks

Example: Siemens

Bam-pa, bom! Taa-TAA troot! Ba-deedle-dee-paa-dooop! Some trademarks consist of a rhythmic structure, a “beat” or identifiable rhythmic pattern.

Advantages

If the rhythm is strong enough it can “carry” any kind of sound and still be recognizable. Put another way, rhythm degrades well. Even if the sounds that make up the rhythm are obscured or distorted, the rhythm will still be recognizable.

Rhythms are also sticky. For example, once you have heard the mnemonic “right-y tight-ee, left-y loose-y,” it is hard to forget.

Disadvantages

It can be difficult to design a rhythm that’s unique enough to be identifiable while also being discreet, especially in a short time frame. In other words, unless you play it loud or there are loud periodic components, it can get lost in environmental noise more easily than other trademarks.

Tone-Color Based Trademarks

Examples: Windows 95, Windows NT, Sony PlayStation, and Xbox startup sounds

Every sound is composed of spectra that contain harmonic and inharmonic sounds. Just like a fingerprint, each of these tone colors, or timbres, is unique.

It is the tone color that makes an oboe sound like an oboe, a violin sound like a violin, and a clarinet sound like a clarinet. It is what we are describing when we use words like glassy, reedy, or woody; it is the precise fingerprint of the harmonic and inharmonic overtones that an instrument produces with each note.

Advantages

It is easy to make a tone color–based trademark unique. There are a limited number of ways you can glue together a short melody, but an infinite number of possible colors of sound. Tone color audio logos would pair well with generative audio. Instead of playing back exactly the same, a set of rules could allow the sound to be played back in a recognizable, but subtly different way each time. This would be a unique approach to a sonic trademark.

Melody-Based Trademarks

Examples: T-Mobile/Deutsche Telekom, Intel, Nokia, NBC

Melody-based trademarks are the most memorable and most commonly thought of trademarks. Beyond familiarity, melody has a lot going for it. Melodies are extremely portable—they can be sung or whistled, for example—and this matters tremendously in the battle for attention.

Advantages

Melodies are also “tone–color–independent.” For the most part, it does not matter what kind of sound you use, as long as it has a periodic waveform, and more tonal content than noise. For example, whether it is a marching band or a melody-playing dot-matrix printer playing it, you can identify the T-Mobile/Deutsche Telekom da da da DEE da.

Disadvantages

It can get old fast. In musical terms, a great many logos use some version of the I, II, IV, and V intervals (this is worth looking up if you’re curious—it’s pervasive in Western music traditions) to try to sound either “perky-happy” or “majestic-comforting.” But what makes something familiar can also make it irritating. If it sounds annoying, it is annoying.

Chord- or Harmonic-Progression–Based Trademarks

Examples: Macintosh startup sound, THX audio logo

Advantages

Similar to melody, chord- and harmonic-based trademarks can function independently of specific tone colors.

Disadvantages

Also like melodies, repeated harmonies can become tiresome if overused. Many harmonies or progressions default to some combination of I, II, IV, and V intervals. It might make sense from the perspective of psychoacoustics, as these are positive progressions, but in the long run, if it sounds cheesy, it is.

Spoken-Word–Based Trademarks

Examples: General Mills’s “Ho! Ho! Ho! Green Giant,” Yahoo!

Advantages

There are relatively few spoken word trademarks out there, and if effective, they can increase the memorability of the name of your company, or your motto. Spoken-word trademarks, such as General Mills’s “Ho! Ho! Ho! Green Giant” or Yahoo!’s “yah-HOOOOO,” are just sounds of a particular shape, color, and duration.

Disadvantages

They can be cheesy or distracting. Because language takes more attention than sounds, spoken word audio logos may not be as calm or unintrusive.

Multi-Faceted Audio Trademarks

Many trademarks combine more than one element. The 20th Century Fox sound trademark, for example, starts with a recognizable marching snare (rhythm), followed by brass instruments and strings playing a chord progression.

The upward steel guitar bwwoooing of Looney Tunes cartoons is an excellent example, which is identifiable by its timbre but then switches to a melody. THX starts with a unique tone color and ends with a majestic chord. However, there will always be one feature that cannot be removed—this is what we might consider the spine of the trademark.

General Advice for Sound Trademarks

In this section, we’ll present some general advice to keep in mind when designing sound trademarks.

Make It Future-Proof

How long do you expect your product to be around? A well-built blender might last for 10–20 years, but software and digital hardware is often traded in every year or two.

To hit a moving target, you need to aim ahead of the current market. Will you be able to switch out sound for your product via a software update? If so, this isn’t a huge risk and allows for more experimentation. But if your sound is “locked in” to the hardware, know that using sounds associated with a particular music style or design aesthetic might sound dated rather quickly. Think it through before committing the latest sonic memes to your product.

Make it Interesting

Use tone color. A more harmonically complex sound is going to stand the test of time more successfully than a simple one.

Make it Short

Brevity wins. As a general rule of thumb, the length and intensity of a sound should be inversely proportional to the frequency of its occurrence.

Most sonic logos have a duration of one to five seconds, although there are exceptions. If a piece of software takes a little while to load, a calm, meandering, long ambient sound could be associated with it. The length of this sound can provide a distraction during the loading time. Other examples are the 20th Century Fox and THX trademarks, which take advantage of their more or less captive movie audiences.

Make it Polite

Make your audio logo recognizable at any reasonable volume, but don’t rely on forcing the user’s attention.

Consider the Sensitivity of Human Ears

Humans are more sensitive to some frequencies than others. Match the sound to the context, and don’t overwhelm the human ear with sounds in the same frequency range. Sounds in critical bands are often overused.

Map Out the Competitive Brandscape

Do some homework and examine what others are doing so you can position your audio logo accordingly. You might need to place your mark in the same emotional space as your competitor in order to leverage the power of association, or you might prefer to strike out into uncharted lands to find a place where none have gone before. You can use the dichotomies listed in Table 5-1 to inform your direction.

| Spacious | Closed |

| Resolution | Tension |

| Natural | Synthetic |

| Classic | Contemporary |

| Unique | Familiar |

| Simple | Complex |

| Woody | Plastic |

| Hollow | Dense |

| Consonance | Dissonance |

| Phrased (example: womple-di-domple-dy) | Exclaimed (peng!) |

| Thick | Thin |

| Longer | Shorter |

| Smooth | Sharp |

| Moving pitches | Static pitches |

| Literal | Abstract |

| One part | Many parts |

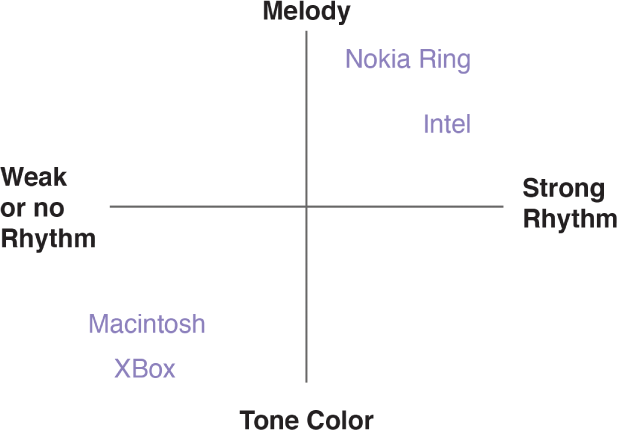

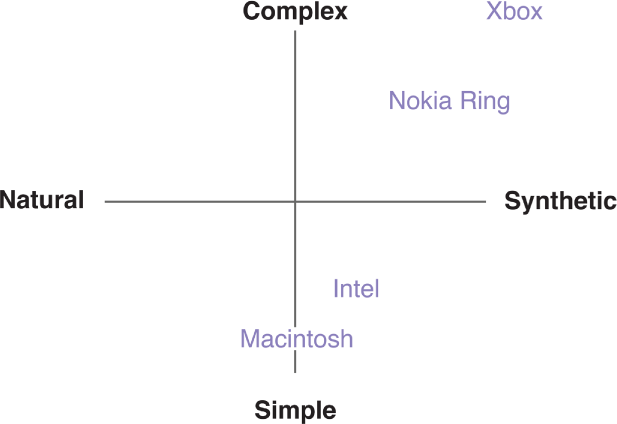

One approach is to start with an attribute matrix or two (see Figures 5-1 through 5-4). This is a fast, easy way to get a feel for the sonic “brandscape” and look for positioning opportunities. Furthermore, most companies’ brand departments will understand this tool.

Figure 5-2. The same sounds on an axis that contrasts rhythm with melody and tone color.

Figure 5-3. The same audio logos on a scale of natural to synthetic, simple to complex.

Figure 5-4. The same audio logos on a scale of complex to simple and short to long.

After laying out the attribute matrix and choosing the style of audio logo, you will use this information to create a design brief, described in Chapter 8, to complete the specification of what you want in your audio logo. Hopefully you will create an enduring and recognizable sonic identity for your brand.

Conclusion

Start with sensitivity and empathy toward your customers’ needs and expectations, and you will be far more likely to be successful with your sound branding efforts.

The more senses you get right, the better the overall experience your customers will have! Never lose sight of the fact that your customers, and the people they know and love, may have to hear that sound repeatedly, for years or even decades. This can be a source of praise or of frustration.

If, after spending months on a sound branding project, you’re able to declare that an upward swooshing sound symbolizes innovation and an F major chord from an expensive Steinway piano connotes experience—and it elicits a positive reaction from the customers who hear it—then your hard work was worth it.

1 Watch the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S_gBMJe9A6Q&t=5s.