Chapter 11. User Testing

When we launched the first Jambox at Jawbone, we thought we were so smart in proactively telling people when the battery was low. That was all good, but when real people started using it, they didn’t turn it off at night and so we’d get reports of this booming, scary voice at 3 a.m., which some people thought was an intruder. Test your product. Test with real people. Test in real settings and contexts.

—KAREN KAUSHANSKY, JAWBONE

USER TESTING IS IMPORTANT.

It is helpful to inform your design by looking at actual user behavior instead of solely gathering decontextualized feedback. Proponents of the Lean Startup method, for example, are skeptical of the utility of asking people to predict their own behavior, and prefers to give people real options and see what they actually do. Some market research and survey responses can be unavoidable in development, but keep in mind that nothing quite replaces observation of real-world use.

The user testing process for sound design is a way to iteratively test soundscapes and design choices at various product stages. It’s faster and less expensive to test sounds before they’re put into the finished device to make sure the sound fits the interaction. Stakeholder listening sessions, web feedback sessions and small focus groups allow for initial decisions to be validated or tossed out. Giving stakeholders a condensed summary of feedback can help provide an external perspective and inform design direction from beyond the conference room. Once user feedback is collected, the most successful soundscapes can be integrated into prototypes that can be tested in context. The last stage of the user testing process is when the product is ready for production and the final sounds and interactions are tested. This stage, along with hardware testing (discussed in the previous chapter), completes the sound design process.

Researching the Domain

If you’re developing sounds for an unfamiliar product or experience, it is crucial to develop an understanding of the different uses and history of your product as well as the general sentiment for what’s currently available on the market.

Take whatever you know already, and gather viewpoints from varying perspectives and backgrounds. It’s important to recognize that you have an individualized bias no matter where you come from. Understand if there is an existing hypothesis about what makes for a good product in your category, and acknowledge that there might be more than one solution to the problem you are trying to solve.

Testing for Inclusivity

Considering universal design and addressing the needs of many versus the needs of the few promotes the development of widely used products that both make money and improve people’s lives.

Aiming for inclusivity genuinely does improve the world for everyone. For example, wheelchair ramps are equally useful for people with pushcarts, those pushing strollers, or those who use wheelchairs. Automatic doors are equally useful for the elderly and a new parent carrying a child in one arm and a bag of groceries in the other.

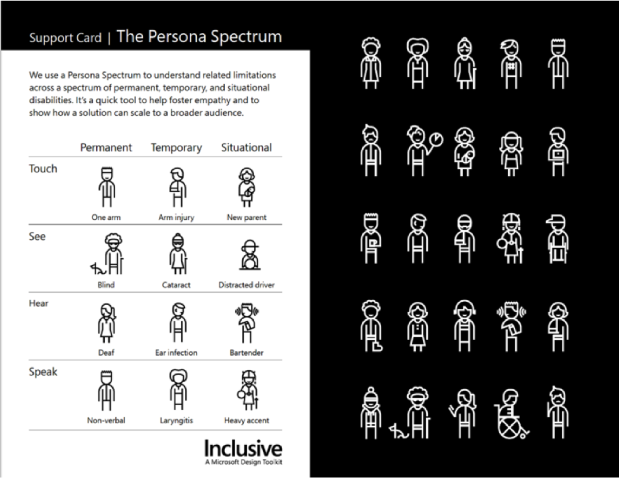

Universal design accounts for those of different abilities. Note that there may be not only permanent disabilities, but also situational disabilities (like the case of the new parent) or temporary limitations (such as a broken limb) that hinder a person’s capacity to perform certain functions for a limited period of time (see Figures 11-1 and 11-2):

- Permanent limitations

- Permanent limitations are those where the loss of ability is unrecoverable. When someone is born without or loses the use of a limb, sight, or hearing, these are fixed, unchangeable situations.

- Temporary limitations

- Some people experience hearing loss in one or both ears as they get older, or a very loud sound can cause hearing loss for a short period of time. These can be temporary limitations, and in these cases, products need to rely on different senses to get information across.

- Situational limitations

- As people move through different environments, their abilities can also change dramatically. A bartender might not be able to hear an order come across the counter because of ambient noise. A caller might not be able to hear a voice on the other end of the phone when a noisy truck drives by. These are situational limitations. We can design better sounds or better environments, and understand the role sound can play in addressing situational limitations.

Figure 11-1. Examples of permanent, temporary, and situational signal blockages and possible causes (© Microsoft 2016, used with permission).

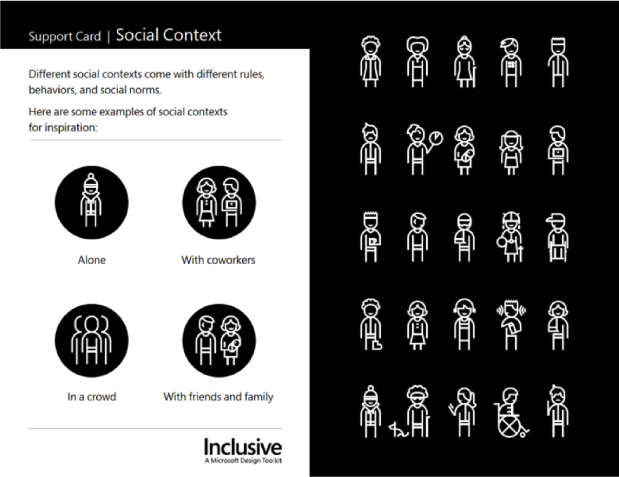

Figure 11-2. Activity card for temporary/situational limitations (© Microsoft 2016, used with permission).

When temporary limitations, situational challenges, and permanent disabilities are considered as a group including hearing loss, blindness, visual impairments, ADD, autism, mobility disabilities, and dyslexia, the number of people affected reaches 21 million in the US alone, and 1 billion worldwide.1

When the use of technology is tested among working age adults, the majority—79%—report experiencing some difficulty with technology. It is essential that your user testing is targeted to assess the ease of use of your product for those with limitations.

Contextual User Testing

We bring our technology with us into different contexts, family situations, and times of day. We need technology that works well in optimum situations as well as edge cases. Because sound is so intensely specific to context, it is crucial to test in the real world, or as close to it as you can reasonably get. Contextual user testing deals with interactions that happen because of time of day, location, noise levels, accessibility issues, or seasonal differences. Each context can influence how a sound affects someone—specifically, whether the sound is intrusive, ignored, or welcomed (see Figure 11-3).

Figure 11-3. Microsoft activity card with considerations for different conditions (© Microsoft 2016, used with permission).

Contextual testing works best when users can take the product home with them or use it on a daily basis. Unless you know the exact context and hardware for a given audio experience, design for ranges of context rather than ideals. Users often hear sounds in situations that are far from optimal, in terms of both environment and hardware: you may be testing in a quiet room over a pair of high-quality speakers, but your users might be listening over a smartphone loudspeaker in a noisy coffeehouse. Take your product out into the real world and test it. Test it with real people. Test it with friends of friends. Play with it on public transportation. Take it into an office, a (relatively quiet) bar, or a grocery store. The results may be surprising (see Figure 11-4).

Figure 11-4. Inclusions for different locations. How will a technology work off-grid in the wilderness? (© Microsoft 2016, used with permission.)

Testing in a purse or backpack

If you’re making a portable object that makes a sound, consider how placing it in a purse or backpack might alter the sound. Even a little bit of material or leather can dramatically reduce the high frequencies, making notifications more difficult to hear. One way to mitigate this is to add a haptic vibration to ensure that the notification will still be felt through the material.

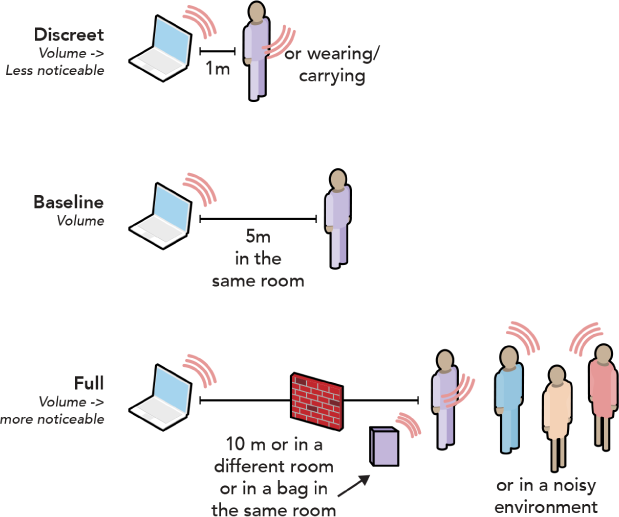

Testing at various distances

In this test, you’ll want to run through scenarios at various distances in order to understand how sounds work at close and far ranges, and how they might disturb people nearby. You might find out that the alarm clock you’ve designed carries very clearly through walls, annoying others in the apartment complex. Here are some possible scenarios:

- In-hand

- On a table

- Across the room

- In another room with the door open

- In another room, separated by a closed door made from cheap, hollow materials

- In another room, separated by a closed door made from solid materials

- In a large open space, like an office or train station

If you need something to be heard from another room and the product has the ability to either vibrate or create low frequencies, then bring these into your design.

Test sound designs close at hand, at medium distance, and through a wall or down the hallway (see Figure 11-5).

Figure 11-5. No matter what you’re designing, you should test your product at different distances to see how it performs. Depending on how close you expect the user to be when the product makes a sound, you will want to adjust the volume of the device to be discreet, baseline, or full volume. Test your sound in a purse, backpack, or back pocket to see how it sounds. Test your sound in the same room as you to see how the sound performs close by and at a distance. Test your sound in a different room to see if you can (or cannot) hear it.

Products that vibrate can vibrate against surfaces they’re resting on, making the vibration audible (think of a phone on a wooden table).

Testing on public transportation

This test is helpful for seeing how other people might hear your device in different public situations and how it might be bothersome. Go with a colleague and trigger a sound while you’re sitting next to each other, across from each other, when the bus or train is full and noisy, and when it is empty and quiet.

Testing on a flight

If you have a member of your team traveling for work, have them test the sounds on the flight. Planes add a particular low hum to the environment that can disrupt certain sounds from coming through clearly. Given how ubiquitous this experience is, it can be worth testing specifically.

Testing in international environments and contexts

If you are planning to release a product to international markets, it is reasonable to expect that different populations will have different preferences and different associations for sounds. For instance, if you’re developing a product that might be used in Seoul, you’ll want to review cultural considerations of politeness and expectations of quietness (or electronic friendliness—for example, some Korean rice cookers play adorable tunes when finished). On the other hand, Korean service sounds do not work well in Europe and North America because they are perceived as too long and annoying in tone color and character.

[ TIP ]

One study on ringtones—“Soundscape Vision” from Samsung Electronics Corporation in 2006—found that “regardless of cultural differences and different user situation, certain attributes were regarded as important by respondents”:

- Warm, subtle, deep tone colors and simple sounds

- Melodies that are progressive in loudness and structure

- Higher fidelity in playback

Test for Social Context

Consider how the product might be used alone, with coworkers, in a crowd, or with friends and family (see Figure 11-6). The social norms when someone is alone are different than when someone’s in a crowd, around close family or friends, and at the office. In the same way that people might adjust their behavior according to their environment, devices that go with us into these environments should be flexible to match our contextual interaction styles. A work alert for someone in a family context is a situational-technology mismatch.

Figure 11-6. Inclusive design support card for designing with different social contexts. Consider how the product might be used alone, with coworkers, in a crowd, or with friends and family (© Microsoft 2016, used with permission).

Giving users the option to adjust or change the alert style or to turn off the alerts completely from a top-level menu can help them adjust seamlessly to social contexts alongside their devices. Here are some aspects to consider in different contexts:

- Alone

- Does the alert interrupt restful time? Does it distract from leisure activities?

- With coworkers

- Does the sound of an incoming alert disrupt people nearby other than the intended recipient?

- In a crowd

- Can the sound of the alert be heard above a crowd? Can it be heard in a loud environment? Would it potentially disrupt a wedding, funeral, or cultural event?

- Friends and family

- Can the sound be turned off or changed? Does it intrude on personal time or romantic time?

- At school

- Does the sound or notification interfere with classroom activities?

Devices are entities that we carry around with us, and they have their own behaviors. Training them to match our behaviors, and to respect changes in our needs or contexts, can help smooth their interactions with us. Creating a filter for messages is one way to organize attention into a range of channels, so that some are intrusive and high level, and others are not. As of 2018, typical smartphone alerts consist of the same ping, no matter the content, sender, or context. This means that there is no hierarchical difference between an urgent alert from the vet about a sick dog and an automated update from a gaming app about a new feature.

Allowing people to set priorities and alert styles according to who is sending the message—friends and family, work, or other businesses—is one way to conserve attention. Messages sent by friends should sound or feel different than work-based or automated alerts. These kinds of audio differences can give an initial indication about the message received. Similar to the Gmail folders that sort “Primary” from “Social” and “Promotions,” diversification of alert styles can help users make better decisions about whether to check the alert based on the context.

Some applications have emoji and screen animations that appear, then grow, shake, and return to normal size. This is the emoji equivalent of making something “loud” and friendly. Another form of animation is message confetti, such as hearts or balloons that rise up from the bottom of the screen.

Haptics could take a cue from these friendly messages by providing options for combined events that include a kind of haptic animation, starting with a small tap and growing to a large swell, to signal that the message is friendly and human. These kinds of messages could be sent only by friends, with different forms used to signal joy, love, or an emergency.

Most users don’t know this, but you can actually set custom vibrations on the iPhone. The Sounds and Haptics menu allows users to “record” a custom haptic style by tapping the phone. This allows users to set very nonintrusive text-message buzzes, making for a distinctive style of alert that is recognizable to the phone owner and also less invasive to others. It can also be made subtle enough that it is unnoticeable when the phone is in the user’s pocket during other activities.

Segmentation and Applied Ethnography

Segmentation is a form of ethnography, or the study and description of the customs, tools, and rituals of people and groups across cultures. In applied ethnography you’re trying to understand and catalog features that define that population. And if there are different opinions or different strategies that you observe within that population, it’s useful to try to identify the relevant dimensions, or segments, that correlate with those differences.

Successful market research illuminates assumptions in the design of the product, or assumptions about its audience use cases that aren’t accurate. Many researchers divide populations in irrelevant, stereotypical ways, such as by race, gender, or social class. Segmentation of this kind can easily overlook what people actually need. Instead, consider focusing on segmentation based on purpose or idea. Having a specific purpose indicates how to best craft a product for people because it’s directed toward an end. These higher-level categories are more likely to span across cultures, backgrounds, and incomes, and the advantage of this approach is that it relates more to qualitative aspects of products.

Malcolm Gladwell’s 2004 TED Talk “Choice, Happiness and Spaghetti Sauce”2 highlights why both qualitative and quantitative research are necessary, and why the answer to a question might not be a single, perfect product, but a range of solutions. Good exploratory research will identify relevant segments with regard to the product or sound you are studying. Gladwell recounts the story of Howard Moskowitz, who was hired by the Campbell Soup Company to do market research for Prego back when all the food companies were trying to develop a single perfect pasta sauce (or single perfect mustard, etc.) for everyone. Moskowitz figured out that one segment of society preferred a chunky pasta sauce, while others preferred a plain pasta sauce. Yet another segment liked spicy sauce. The population divided roughly evenly, with about one-third preferring each category. At the time, no one was making a chunky pasta sauce, so the preferences of that segment of the population were going unmet. Once this was discovered, Campbell’s could tailor its products more specifically to those groups. Instead of segmenting along race, gender, age, or income lines, Moskowitz worked to determine the preferences that ranged across traditional segmentations, creating a set of products that gave everyone a choice based on purpose and intention.

It is challenging to successfully identify segments within your demographics that give you more information than your original hypothesis, but it is a crucial way of discovering how to build products that meet people’s needs.

Formats for User Testing

Testing potential sounds, soundscapes, and notifications before a product is built involves playing different sets of sounds to stakeholders or user testers in person or in a web survey format, gathering their feedback and recommendations, and condensing that information into excerpts and actionable steps. This can be done in different ways, either remotely or in person, using sounds alone or physical prototypes of the device.

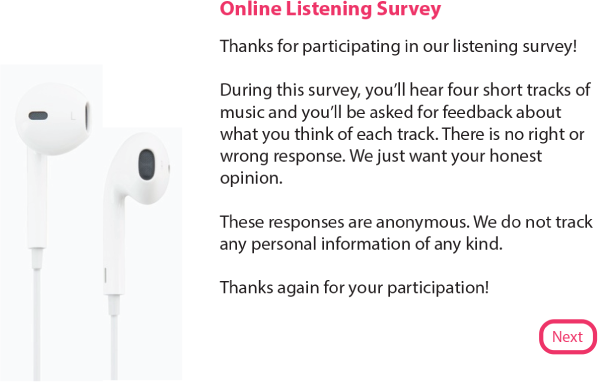

Online or In-Person Surveys

One of the great challenges of asking people to give feedback about creative efforts, such as graphic design or music, is that they generally want to be polite and not risk offense. Consider creating an online listening survey where your test group can “audition” the different brand-soundtracks, rate them from zero to four stars, and leave written feedback.

Whether you’re testing in person or over the web, it’s important to make sure your listeners experience the sounds in a similar context with similar playout technology (see Figure 11-7). This will avoid skewing the data with factors that can be prevented. For a web survey, you might tell people to set the volume to 40% of their device’s max output, and to listen on Apple Airpods. Listening on a specific set of headphones negates many of the effects of context, such as room acoustics and environmental noise, while unifying the listening experience. The survey could also ask what headphones or earbuds users are listening on, and this information could be associated with reviews of the experience. Likewise, when testing in person, standardize the interface, playout, and listening hardware. For instance, you might give everyone a set of headphones and an iPad demo, and request that testers not change the volume during the demos.

Figure 11-7. Landing page and instructions for an online test tool used to play branded soundtracks for review. Requesting specific playout hardware ensures that the sounds are being heard the same by all participants. Alternatively, a survey could request details about the hardware that the user is playing the sounds on to be identified, in order to understand how specific hardware might alter the favorability of a given sound set.

Well-presented feedback is useful for convincing stakeholders to remove negatively reviewed sounds. Internal stakeholders might be attached to specific melodies or choices, and reviewers can give you the power to convince them to let go.

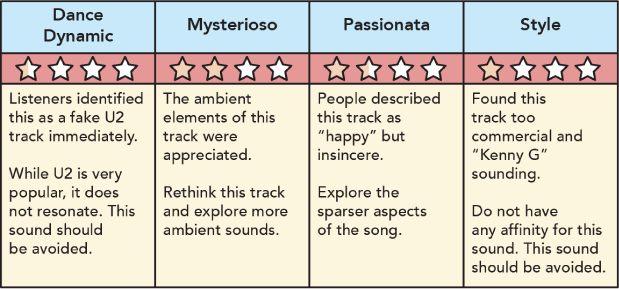

Remember that any presentation you deliver to a stakeholder will likely be shown again to someone else inside the company, without any accompanying description from you. Clear, simple presentations work better than complex ones that need elaborate explanation; see Figure 11-8 for a good example.

Figure 11-8. Presentation to client: summary of listener feedback from four different branded soundtracks. Reviewers were asked to rate the tracks from zero to four stars. The average of this was presented as an overall “grade” for each track.

One-on-One Sessions

In-person user testing with prototypes works best one-on-one, with a designer present to observe and manage the test process. This method of testing is good for when the product is still being developed and you want to try alternatives or determine if your initial design hypothesis is heading in the right direction.

One-on-one user testing also works best with realistic questions. For instance, if you want to test the search function, say, “Your friend told you about Introduction to Photography 101, and you want to look it up,” rather than, “Search for something that you find interesting.” Have participants complete the exercises with as little involvement or direction from you as possible. Then, using the guidelines described in the next section, make observations about what it is they’re doing.

Consider that small problems can cover up other problems

People might get stuck on initial problems and not even have an opportunity to get far in the user flow. People naturally gravitate toward the most prominent errors, those that are the most glaring and most central to the flows you’re testing. Fix the initial challenges to see if they’re covering up other issues.

Simulate busyness, stress, or distraction

People will often end up using a product when they are busy or stressed, but this can easily be missed during in-person testing. One way to simulate busyness is to give testers something difficult to do, like “Start with the number 17,000 and count backward by 13.” To add stress, ask them to go faster. When your product is playing a sound or the user is trying to get something done, you’ll be able to see very quickly whether the sound is annoying to them.

A word of caution here: although simulating stress might give you important feedback, your test subjects will not appreciate it, especially if you make them feel incompetent. Make sure you keep the well-being of your test subjects in mind as you design the stressor.

Determine user questions and executional components

If you’re testing a new voice user interface product like Alexa, you have to assume that people don’t know what to do with it. What voice commands are there? What are the product’s limitations? How can you turn it off and on? In this case, you can try different terms for actions and test how recognizable the terms are.

How a stakeholder labels an interaction might be completely different from how a user sees it. When you’re talking to users, they don’t care about that. Users can learn how to say, “Hey Alexa” without ever knowing that, on the stakeholder side, “Alexa” is a wake word. All they need to know is how to get the device to pay attention to them. It’s important to keep those labels clear among your stakeholders, though, and keep the terms aligned with how success is being measured for the project.

Focus Groups

Focus groups usually involve 8–10 people around a table or on couches being led through a discussion by a moderator. Sometimes the client will suggest focus groups, but they are often not as useful as one-on-one sessions. Remember that big personalities can sway opinion, whereas individual tests can make people more comfortable being honest about how they perceive your products. If you find that a single individual is dominating the conversation, consider not inviting them to future studies. Make sure to allow time for discussions with individual group members after the session. Consider spending more time with the quietest members of the group, as they may be the ones with the best listening skills, and produce solid perspectives and valuable ideas.

When using a group, 8–10 people is enough. Smaller groups are easier to track and communicate with, and they’re easier to meet with more frequently. More than 10 or 12 people, and you’ll see a lot of repeated observations. This doesn’t mean that you won’t learn anything new, but you will lose valuable development time and see diminishing results from the effort. It is more useful to iterate the product multiple times and gain new insights from small groups than perform fewer tests with large groups. Ensure that you have a diverse range of people in the group. Try to identify patterns and what drove certain decisions or actions. These are the areas to pay attention to.

When successful, open discussions can pave the way to new, unexpected results. If your stakeholders require focus groups, consider how general conversation might give people a vocabulary and shared experience with which they can make helpful assessments about the sounds devices make, or help direct a design focus for the overall project.

Research Your Personas

Personas are dangerous if you’re just making them up. They need to be informed by market research and interviews. You need to have empathy for human lives and the difficulties people face, not just account for the times when things go right. Part of this process is finding useful markers. More and more there are properties that cross traditional boundaries—like with video games, where the defining feature is not related to age, gender, socioeconomic status, or ethnicity, but a new cultural mode of being.

There can be big differences between individuals assigned to the same demographic group. For instance, some millennials might still live with their parents, but many are well off and live alone. Some have children, or married early. To place everyone of a certain age group into the same persona (“millennial”) misses the point. When developing products, functional definitions related to someone’s values, context, and goals are more important than abstract categories. Make a product that works for a range of situations instead of one that works only on a demographic assumption. Then you’ll have a product that can become a classic instead of a cloistered, brittle one.

Review the Final Checklist

The best product testing involves sending a device home with testers so it can live with them for a while. Contextual testing is about simulating the environments and situations a technology may encounter during its lifetime. There are many issues to consider. Whether or not you perform a home test, review the following list to ensure you have covered everything in your studies.

Sound

- Poor sound quality (distorted)

- Wrong pitch (too high- or low-pitched, or a pitch that conflicts with the surrounding environment)

- Wrong volume (too loud or too quiet)

- Can the sound be turned off or changed?

Time

- Ill-timed (wrong place or situation, wrong time of day)

- Mismatched with the user interface (aesthetic or timing)

- Wrong duration (too long or too short)

- Played too frequently or too infrequently (Microsoft Outlook notification, stock ticker or energy usage, a dangerous truck backing up)

Attention

- Wrong level of urgency (too alarming/forcing attention or too subtle)

- Played without reason (does it inform?)

- Interruptive to others (a sound meant for a single person is played for many, sound travels through apartment walls, or sound goes off in a quiet theater)

- Is speech necessary to the success of the product? Does the addition of speech increase cognitive burden? Do you have the resources necessary for speech translation?

Inclusion

- Does the device still work for those with temporary, situational, or permanent disabilities? Those who can’t see, speak, hear, or touch? Consider running the product test through Microsoft’s Inclusive Toolkit activity cards.3

- Can the notification be changed to haptic, visual, or light-based depending on the needs of the user?

Conditions

- Does the device take into account time of day? Does it have sounds that will go off in the middle of the night? Does it take into context the sleep/wake cycle?

- How does the device perform in loud or quiet environments?

- Have you tested how the device sounds in another room, on public transportation, in the user’s hand, or in a purse or backpack?

- Have you tested connected devices in areas with poor WiFi connectivity?

Presenting Your Findings to Stakeholders

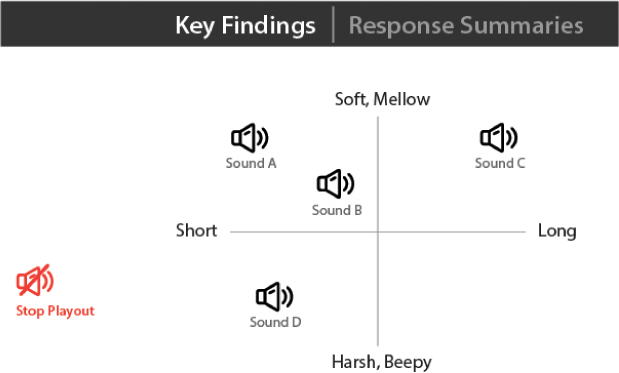

One of the most important reasons for user testing is to get actionable content, but often this content can fill dozens of pages. You don’t want to overwhelm your stakeholders, but you still want to be informative. Infographic presentations are useful for showing what you have learned clearly and concisely (Figure 11-9).

Figure 11-9. A client presentation. Focus group feedback was converted into a clickable interface so that the client could hear the sounds in context with the positioning assigned by the participants. Response summaries are organized in a different tab so that the client can see highlighted responses from participants.

Conclusion

User testing is an important way to test and reframe ideas or hypotheses you or your stakeholders have about a product. Preproduct testing is helpful when a range of solutions or scenarios has been developed and you need help deciding which one is best. With prototype testing, context is most important. Although one-on-one interviews are preferred, focus groups can have benefits as well. Be careful to consider how different sounds might need to be altered to fit different environments, ability levels, and cultural expectations.

User testing is also a valuable way to incorporate user feedback into the decision-making process. Don’t overwhelm your decision makers with too much information, however. You’ll want to give them direction and conclusions in a succinct, actionable way—such as with an infographic presentation—that helps move the product to production.

1 Anant Maheshwari, “AI for a billion people. And an accessible world,” Microsoft, http://bit.ly/2RBaHs4.

2 See http://bit.ly/2Q07z8Q.

3 Microsoft Inclusive Design Toolkit, http://bit.ly/2DqFRQ3.