CHAPTER 4

On the Set

A shoot is a massively complicated, expensive affair. Films vary in scope and budget, each crew has its own personality, and every scene has its own set of problems. But any shoot requires planning and understanding among the players. Yes, experience and skill and talent are vital, but shooting a movie is a team sport, and if you're not in sync with your team members, something bad will most certainly come about.

One of the sad truths of movie production is that the films that can least afford trouble are often those laden with grief throughout the entire production line. Big, expensive films have more … well, money. Alien XII will be in a position to hire the best grips and gaffers, an experienced (and large) sound crew, and a postproduction coordinator who can navigate the pitfalls of finishing the film. My Mother's Napkin, on the other hand, may have a crew of seven recent film school graduates who have to guess their way through the production. Which film is likely to walk into traps? And which film will have the resources to free itself from those jaws? It's unfair, but those who can least afford it usually find themselves with the most complicated postproduction messes. But many of these budget-busting problems can be avoided with a bit of preproduction face time.

Dialogue editors are parked right in the middle of the filmmaking post-production process. In order to do your job well, with confidence, you must know what happened before you got hired, and what will happen once you're finished. You don't need to become a location mixer to be a good dialogue editor, but understanding the issues facing the sound crew will help you to know what to ask for and to comprehend what you get. And knowing how the camera department does its job will tell you something about why things are the way they are. Visit the set—at least in your mind— and you will better grasp the job facing you.

Producers often don't understand how important it is for the location mixer to be part of the scouting process. If I know in advance what I'll need—whether sound treatment, extra mics or cables, or some sort of specialty gear—then I have time to organize myself, and there's a good chance that the production will approve the extra costs. But if I learn the realities of the set and the scene on the first shooting day, I'm forever reacting to one disaster after another.

Hire the location mixer to visit the shooting sites and everything goes better. I can better coordinate with the gaffer to put cables in sensible places and negotiate where to put lights as well as microphones. We all win.

Tully Chen, location mixer

Mon trésor; Sharon

The Picture Team

Let's face it: The shoot is about picture. It's not fair, but there is a bit of logic at work. Even though we, the sound people, want to capture clean, tight dialogue that contributes to the story and respects the space, we can, in a pinch, replace all the production sound with ADR and Foley. The picture people can't do that. Aside from the occasional digital sleight of hand, the camera really needs to get the shot. Not surprisingly, the picture team is pretty big.1

Camera Department

These are the Top Gun strutters of the set. It's all about picture, and they know it.

- Director of Photography (DP or DoP) Alpha male (or female). With the possible exception of the assistant director, this one runs the set. He's responsible for everything image: composition, lighting, motion. On giant shoots, there's someone else to operate the camera. Otherwise, he will manage it.

- Assistant Camera In charge of camera and its surroundings. Sits right next to DP. On smaller shoots, she's in charge of focus, and possibly the person with the clapperboard.

- Focus Puller Quite literally, the person responsible for getting and maintaining focus. It's harder than you think. As Digital Cinema replaces film, this job is becoming increasingly technical. On smaller jobs, this position is filled by the assistant camera person.

Electrical Department

There's a lot of electricity on a film set, and not just between actors. The electrical department is responsible for wiring lights, placing the lights, managing the generator, and maintaining a safe environment.

- Gaffer Head of the electrical guys. He oversees light placement and electrical needs, following the lead of the DP.

- Best Boy Electrical This odd title describes the main assistant to the gaffer. She sports almost all the skills of the gaffer, and will likely become one someday. One of her jobs is to dispense equipment from the truck and to manage the inventory. Otherwise, she's an on-set electrician.

- Electricians, as necessary Large, complex films need extra electricians.

The Grip Department

Grips move things. Walls, stands, dollies. They also build things. At first glance, this seems a trivial job, but only to those who consider holding a microphone boom an entry-level position.

- Key Grip Head of grip department.

- Dolly Grip Responsible for moving the camera dolly. He must understand the scene, know how to move a rather heavy camera/camera operator/assistant camera combo without making noise, and manage to do all this the same way on each take. On smaller films, the key grip assumes this role.

- Best Boy Grip As you'd assume, this is the assistant to the key grip. On particularly complex scenes, extra grips are used; they are called “extra hammers.”

The Sound Team

Most small films have a two-person crew: a location mixer and a boom operator. If a film is better endowed, there will be a third crewmember: the cable person. The roles are well defined, but the boundaries tend to blur.

Location Mixer (or Sound Mixer)

The head of the sound team, the sound mixer, is not to be confused with the ADR mixer or the rerecording mixer, both of which show up much further down the sound pipeline. He is responsible for assessing the sound needs for each scene; what must be done to capture the important narrative elements of the scene, and what equipment and logistics will be needed to pull it off. Whereas other members of the sound team are on the set, in the thick of things, the location mixer usually sits nearby with his sound cart. This portable sound control center boasts recorders, radio microphone receivers, preamps, a mixer, a computer, and a video monitor showing a feed from the camera (see Figure 4.1).

The sound mixer typically routes several tracks to the recorder, or recorders— each track separated from the others—so that you, the dialogue editor, will have access to individual microphones. Additionally, he will create a live mix that follows the action of the scene—fading this in, fading that out— creating a mix with a continuous flow. This mix will be used by the film editor during picture editing, since she rarely wants to edit with lots of separate tracks. Only later, in audio postproduction, will these individual, isolated tracks come into play. The job title, “sound mixer,” dates from the days before multitrack recording (that is, up until just a few years ago), when location sound had to be recorded onto one mono track (or later, two channels). Whether recording a single boom or two booms and two radio mics, the location mixer had to make live, irrevocable, decisions. Miss a cue and that's it; the line is not on tape. Multitrack recorders do provide a bit

|

Figure 4.1 |

|

of a safety net, since each input channel is isolated from the others, but the live mix is still crucial for capturing the energy of the set.

Production mixers have it tough because they don't have enough support on the set. And yet months later in an editing room, the director and editor wake up and ask, “What's that hum?” It's the generator that your production mixer kept telling you about. “What's that buzz?” It's the fluorescent lights that you didn't take the time to turn off. “What's that rattling sound?” It's a loose gel on a light that your mixer told you about but you wouldn't wait for it to be fixed.

It's sad that so much time is taken to make sure that each shot is lit properly, yet hardly any time is devoted to making sure it all sounds good. Film is not just 50 percent visual and 50 percent aural. I think that sound, since it is able to envelope us, creates much more of the visceral experience of a movie that just what our eyes see. After all, sound is the first sense we develop in utero, when we cannot see a thing!

Vickie Sampson, dialogue editor

Pirates of the Caribbean; Sex in the City 2

Boom Operator

The boom operator controls a microphone that's perched at the end of a pole. This enables the “boom microphone” to be where it needs to be. This much is obvious. But there's much more to this job than holding a very long pole with a rather heavy mic at its far end. She must know the script and action for each scene. If the mic's not in the right place at the right time, then the line will be recorded off-mic, a problem with no cure other than resorting to alternate takes or ADR, both of which are time-consuming; neither of which very satisfying. The boom operator must understand how lighting works, so as to avoid shadows cast by the boom or mics. She must understand where the camera is and where it will be. Since the object of the game is to get the microphone close to the action without letting it get into the shot, the boom operator has to study the shot and pay attention to the focal length of the lens.

Usually, but not always, it's the boom operator who places radio mics on the actors. This involves a decent knowledge of fabrics, glues, and tapes, an understanding of how clothes are constructed, and experience with microphone placement. And good people skills don't hurt when attaching a radio microphone to an actor.

Cable Person

Sometimes called the “sound utility,” the cable person keeps the sound department's cables in order so the set stays safe. He takes care of assorted chores, keeps an eye on the boom operator, and when a scene calls for two booms, he's on.

Other Departments at the Shoot

Along with the rather obvious camera and sound crews stand a rather impressive assortment of people:

- Direction: the director, assistant director(s), continuity person, and other support people

- Wardrobe, makeup, and props

- Production company people

- Wranglers and greensmen

- Drivers and security

- Craft service (someone has to feed all these bodies)

This list gets bigger or smaller, depending on the budget and makeup of the film. In short, there are lots of people on the set, each with a job to do. To get something done, you must fit in to this spectacle.

Sound Equipment

Unlike the camera people, the location sound department doesn't come to the shoot with trucks and trucks of equipment. Our challenges are huge, but our arsenal is rather modest.

Microphones

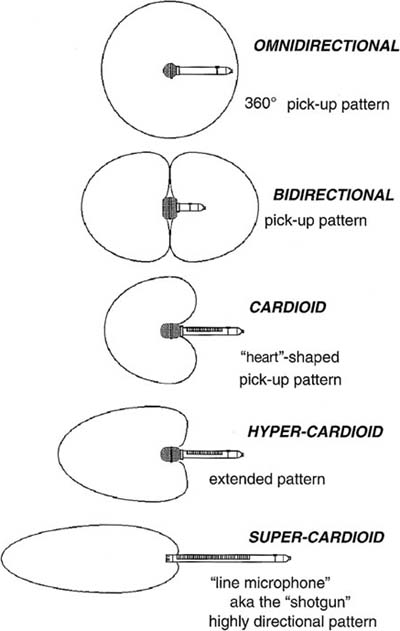

Rarely does “one size fits all” really fit all. This is certainly the case with micro phones. If you're planning to save up and buy a “field recording micro-phone” to set you up as a location mixer, you'll find yourself sadly under-equipped. Different circumstances require different mics: different pickup patterns, different manufacturers, different models. Each present different possibilities, as well as different traps. The most basic choice is pickup pattern (see Figure 4.2.) What focal length is to the cinematographer, so is pickup pattern to the location mixer. A short focal length reveals a wide image. Similarly, a wide-pattern microphone—omnidirectional or bidirectional—is sensitive over a very wide sound field. A long focal length lens is much

more selective, focusing on a narrow field of view. Such is the case with a hypercardiod or supercardiod microphone. These highly directional mics are very effective in ignoring much of the surrounding noise, but are completely unforgiving of a boom operator who misses a cue or an actor who steps off axis. Each pattern has its place. Clearly, you'll pick a different microphone for a relatively quiet scene inside an acoustically lush medieval church than for an exterior shot near a factory.

“One size doesn't fit all” extends to microphone manufacturers and models. We take it for granted that the sound and color of loudspeakers, amplifiers, and workstations that we use to edit dialogue vary by manufacturer.

Such, of course, is the case with location mics. Not only are there the matters of personal taste, but also the needs of the scene, and the idiosyncrasies of the location.

Despite your cache of boom mics, there are times you must resort to radio mics. Everyone hates radio mics, just as everyone hates ADR. But occasionally there's no other choice. As a sound mixer, radio mics pose several problems. First, you need lots of them. If you have five characters in a scene and you must cover all of them at the same time, well … that's five mics. Radio microphones are the Humvees of the set. They guzzle power, and they aren't shy to tell you when it's time to feed them more batteries. Whether clothing rustle, an over-excited actor's heartbeat, or some sort of radio interference, something always seems asunder with radio mics. And finally, there's an unfortunate link between sound quality and the cost of radio mics, so if you're going to get into the radio microphone game and you want to do it well, you're going to part with some cash.

Recorders

People still record with Nagras. People still record on DAT tape. But these are the exceptions to the rule. Record location sound these days and its all but certain that you'll use a multitrack recorder with a hard drive or some sort of solid state memory. Multitrack location recorders offer many advantages over recording on tape. Most notably, there's no tape and very few moving parts, so the machines are pretty robust. Figure 4.3 shows three commonly used hard disk location recorders. You can record four, eight, or more tracks, so you can easily have one or two boom mics and several radio mics, along with a field mix. For dialogue editors, these isolated channels can be a godsend. If the tracks contain the clean information you need, there's a good chance you can fix lines that would be out of reach from within a mix track.

The Location Mixer walks a fine line between making the best of his work and getting the producer to call again for another job. I can see a tendency to “send the problems to postproduction.”

Rubén Piputto, location mixer

Historias Mínimas; Retornos

Syncing Picture and Sound on the Set

Anyone reading this book knows that sound and image are initially synchronized with a clapperboard. That tells the assistant picture editor how to line up picture and audio. It provides a way for the dialogue editor to check sync, if needed. But it doesn't tell you anything other than “start here.”

To quickly find the same frame on both sound and image files, you need timecode. Video and things that resemble video, such as Digital Cinema, naturally have timecode, and this information can be shared with the sound recorder. Camera and hard disk recorder can synchronize timecode through a radio link or cable, but the most common solution is to equip each device with a very good timecode generator running time of day NDF timecode. Both will show the same time you see on your wristwatch. This may later prove useful, since knowing when a shot happened may give you a point of reference for wild sound or other treasures. To compensate for any drift between the two machines, it's normal to jam-sync the timecode generators to each other twice a day.

Despite all this technology, don't be complacent. Common timecode between camera and recorder is no guarantee against sync trouble; use the clapperboard for each take. Not only will the quaint sticks marker give you another sync reference, but scene, shot, and take will be announced each time the camera rolls.

A few new problems

Digital Cinema offers a world of new opportunities for filmmakers. But cherries for the director and camera people can be the pits for the sound department.

- Cameras like RED, Arri Alexa, and others can capture images with relatively low light levels, so a DP can paint a scene with far fewer lights. This means that setup is quicker. Great, right? Except that this may mean that the sound crew lacks the time necessary to assess the scene, work with the grips to determine microphone placement, and find a home for the sound cart.

- Using fewer lights means a greater dependence on practical lights.2 When using normal movie lighting, a lot can be done to prevent boom shadows. But there's not much you can do about the lights that are stuck in the ceiling of the room.

- The process of shooting Digital Cinema is much more postproduction oriented. In short, you can pull off miracles in the grading room—far more than you can do on a film-originated project. One more reason the rhythm of the set is much, much faster.

- After about 11 minutes of shooting, a traditional camera must stop. It's out of film. This provides a rhythm for the set. It doesn't take long to change a film magazine and slate the next take, but it's a moment nonetheless. This gives everyone on the set time to breathe. A Digital Cinema camera can record for more than 20 minutes, and that's bound to get longer. If a director chooses to go through a scene several times without a break, it's tough on everyone, especially the boom operator.

Sound Reports

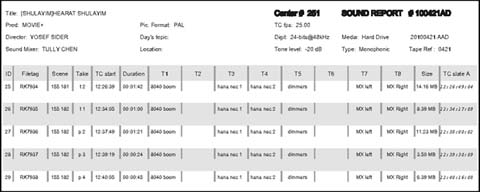

Regardless of how pristine your tracks, despite your sublime interpretation of the scene, no matter the finesse of your field mix, if the postproduction people can't figure out what you recorded, it might as well not exist. Even without your paperwork, an editor can likely figure out that 72B-tk3 follows 72B-tk2. How, though, is he to know that between those two takes you recorded a yak eating an iPhone? Without paperwork, there's no chance that he'll even look for that once-in-a-lifetime wild recording. You have to take notes. Whether it's wild dialogue, room tone, wild production effects (PFX), or sync sound, you've got to write it down. Before there were smart multitrack recorders, sound mixers took notes by hand (see Figure 4.4).

These days any hard disk recorder will create some sort of sound report, whether as PDF files or Excel spreadsheets or text files (see Figure 4.5). This is spectacularly useful for dialogue editors, since you can search, sort, merge, and customize a computer file, all of which are impossible with handwritten sound reports. And a bonus of these machine-generated sound reports is that you can always read them. You will run into many hurdles as you edit production sound, but bad handwriting is pretty well a problem of the past.

Metadata allows you to store information about scene, shot, take, time, recording details, and pretty well anything else you'd like to pass on to those downstream. The most vital information is stored automatically once the recorder is set up. We'll discuss using metadata in Chapter 7.

Getting What You Need

Jumping the technical, acoustic, artistic, and political hurdles facing the sound department seems a huge challenge. But with planning, good negotiation skills, and blind determination, you can usually get the sound the scene deserves.

Plan Ahead

If you're the location mixer, go on the scouting trips. Learn what you're up against and then begin to plan what you can do to make the location's acoustics a bit friendlier and its noise a bit less obscene. Meet with the director of photography to coordinate frame rates, sample rates, shot name conventions, timecode, and other such set-related matters. If possible—this one's a stretch—talk with the picture editor and dialogue editor. A very small

adjustment on your part could mean a huge quality-of-life difference in the cutting room, and a seemingly trivial decision in the field can wreck lives. Meet with the supervising sound editor, since she is the archangel of the post sound cosmos. And be on good terms with the assistant director, who serves as the traffic cop of the shoot. You want that extra moment to record room tone? You need an on-set diplomat? He's your man.

If preproduction meetings prove impossible, then at least put yourself in the place of all these players and ask yourself what you would need from the sound recording crew in order to do your job well—and what you need from them in order to get your job done.

Remember that the hordes at the premiere of My Mother's Napkin won't hear your raw recordings, but rather the combined efforts of everyone down the chain. Make the postproduction crew happy and people will think you a genius. Be a maverick and you'll compromise everything.

Grab wild lines when you suspect the shot is impossible. Plant spot mics in those places where a boom can't reach. Think of those into whose hands you're entrusting your reputation.

As a work philosophy—and this goes for more than dialogue editing— always try to make the next person look good. You will be thanked and rewarded by being hired again and again.

David Barber, MPSE, rerecording mixer,

supervising sound editor

The Killing Room; The Frozen Ground

Respect the Rest of the Crew

Unless you're on the smallest of student films, NEVER TOUCH A LIGHT. This is not your turf and even if a light seems utterly silly and it's right where you need to be; ask, don't touch. You don't want a guy toting a hammer to grab your $3000 Schoeps? Stay clear of his Redhead. Strictly by the book, gaffers hang lights, grips adjust the coverage of the lights using flags, and the camera folks tell them what to do. No one will let you get away with your boom casting a shadow, and no one will let you solve the problem on your own. Show up on set while grips and gaffers are setting up for a scene. Figure out what they are up to, and devise a way to get what you want. Act now and you'll likely get all the help you need. Wait until the last minute and you'll receive all the nasty looks you've earned.

Give the Post-Production Team What They Need

Each film has its own peculiarities, but, for the most part, the picture editor and the sound editors will want—at the very least—the following items:

- Clean, tight recordings that sound good and reflect the spirit of the scene (a lifetime of sound recording may qualify you for this one). Provide plenty of headroom in your recording and be certain that your program material makes sense with respect to the-20dB reference tone.

- Sensible use of the many tracks available on your recorder. Well-recorded tracks that don't make any sense don't help anyone.

- A good mono (or two-channel) field mix for the picture editor. If possible, talk to the editor to find out what kind of a mix she wants.

- Pre-fader (or at least stable) iso tracks! Do all the mixing you want on your mix, but don't touch those iso tracks.

- File names that reflect the slate and the shooting script. Be careful of non-alphanumeric characters such as “/” (slash), “–” (hyphen), “_” (underscore), and the like, and ensure that any non-alphanumeric characters are legal on all operating systems that the files will encounter. You and the picture department must use these characters in exactly the same way. Otherwise the region names and EDLs may not match the sound file names, thus making it cumbersome for the dialogue editor to find alternate takes.

- Room tone. Record it as often as you can (more on room tone in Chapter 11).

- Wild dialogue lines whenever your gut says you need them (more on wild lines in Chapters 11 and 14).

- Wild PFX and atmospheres.

- Good sound reports. If the editor can't find your wild sound, it doesn't exist. If you must write the sound reports by hand, make sure the average person can read them.

- Keep a copy of the recordings in case the editing studio burns down or the bicycle messenger with your disk has an untimely meeting with a bus.

What makes me happy in a dialogue predub? Clean, well-recorded dialogue tracks and an organized and logically laid out cut. Clean tracks, without distracting noise from the camera, set, or environment, with little to no clothing noise, and properly mic'd for full frequency response; that not only makes my job easier, but also that of the dialogue editor.

Tom Fleishman, rerecording mixer

Silence of the Lambs

Listen Before the Camera Rolls

Sets are noisy places. Wind blows, air conditioners roar, refrigerators rumble, transformers hum, traffic does whatever traffic does. You may walk onto a set and not notice these potential disasters, but when you record in this seemingly innocuous space, these background sounds leap to the front. Your brain is used to canceling out noise that an untrained ear may miss. But a microphone soaks it all up. You simply have to pay attention. The list of perils is endless, but here are some of the more obvious noise infiltrators:

- Air conditioners and other air handlers Heating, cooling, ventilation. They make a hissy broadband noise (the air), as well as a low-frequency rumble (the motors and compressors), and they spell doom for your tracks. Turning off the AC of the space where you're shooting may not be enough: if there are other blowers nearby or other compressor units on the roof, your problems won't go away. Walk around the site to find the sources of these noises, and then shut down what you can. This is a good time to be aggressive—apologize later.

- Refrigerators, freezers, and the like Turn off what you can, blanket what you can't turn off. These appliances make far more noise than you suspect, so act with determination to make them quiet. Plug things back in as soon as you can, lest you spoil Grandma's meat.

- Hum Lights are the most common cause of on-set buzz. Work out deals with the camera department to move ballasts to less obnoxious places. Improperly grounded devices will also create hum—think of the noise when you plug your guitar into an amp. (What to do? Talk to the gaffer.)

- Generators Lights consume enormous amounts of power, so a generator is often needed. These things really make noise, so professional shoots hire a specialized, isolated generator and park it as far from the set as is practical. My Mother's Napkin likely can't afford such indulgences, so borrowing Dad's Home Depot generator is the only choice. It will make noise, so rent as much power cable as you possibly can and put it around the block. Still, you're going to hear it.

- Outside noise A bad location is a bad location, but you can mitigate noise by putting up as many sound blankets as possible, any place off-camera— you can't use too many noise-absorbing blankets. They will also help reduce reflections in a space that's too hard, too empty, or too big. Close all windows that are not in the shot, despite the complaints of the crew.

- Set noises Back when films were actually shot on film, cameras made a clicked, purring sound. You could get rid of much of this camera noise with the classic UREI 565 “Little Dipper” notch filter. Now, Digital Cinema cameras sound like tiny vacuum cleaners. It's not that they're so loud, it's just hard to get rid of their broadband noise. Either way, noise is noise. Over-noisy cameras can be covered with blimps or barneys to tame the sound, but you need to coordinate this with the camera people. This is why you have preproduction meetings. Then there's the dolly. When a dolly moves, wheels turn, feet step, and rails can groan. There's not much you can do about wheels and the feet, but if you find the dolly track groaning and creaking as the dolly travels over it, ask the grip to put wedges under the track in places where it's not touching the floor. It's usually the flexing of the track that causes the most annoying sounds.

Do what you can to control these noises, and then try a brief test recording, under conditions very similar to those of the actual shoot. Make this test late enough so that most of the noisemaking demons are in place (lights, generator, AC switched off, etc.), but not so late that no time is left for fixes.

As editors we're used to trying again: combining takes and using wild lines, replacing recalcitrant lines, and processing what is ugly. We have many opportunities to get it right. In the field you have one shot at it. You have to get it right.

_______________

1. Thanks to director of photography Gideon Porath for his insight into life on the set.

2. Practical lighting, like practical music, originates on the set; it's not “artificial.”