2. Titans

The Great Midwest Mounted Valise

July 1974

I arrive in New York’s Penn Station. It’s a steamy morning. I am filled with the energy from my European experience and armed with examples of design unlike anything New York has ever seen. I carry them in a large sample case made of black bonded leather, quite possibly the largest sample case that can be carried by a single human; nothing less could hold the voluminous ideas I have to offer. My friend Otter Hallstein finds it comic, and dubs it “The Great Midwest Mounted Valise.” Something about the name fits: a dominant aesthetic that rides east and arrests the attention of New York. Absurd, impractical, and hi-yo, Silver!

To begin my assault on New York, I have three telephone numbers on an index card. The first is for Dan Small, a fellow creative squid from Cleveland, who, according to his mother, has a great job in the fashion industry and can undoubtedly get me some gigs. The second is that of Walter Papillion, a creative director in advertising whom I met at a university lecture and who will surely get me some interviews at top agencies. The third is for Ed Gottschall, the executive director of the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA).

Penn Station becomes my office, my toehold in New York City. There is a telephone center: thirty telephone booths in two banks flanking a desk where one can obtain change and assistance with overseas calls. The booths have small, upholstered seats, and each booth has a bifold door with glass panels. Closing the door from the inside activates a light and a ventilation fan. The crucial amenity for a job seeker is a steel shelf, just big enough for taking notes.

In Pittsburgh finding my first job after graduation took two weeks, so with two years of professional experience under my belt, New York should be ... no big deal.

I enter Booth 6 confident that one of my three contacts will quickly lead to a great job with a slick office. Over the course of the next three minutes, I leave three messages. Not to worry, several things to do. First, find newspaper, review want ads. Next, examine the other phone booths. The portfolio that New York is breathlessly awaiting does not fit in Booth 6, and I wonder if perhaps one of the other booths might somehow accommodate it. I also need to explore Penn Station for food, a shoeshine stand, a street map, and some three-by-five cards.

Penn Station Booth 6

Booth 6, selected impulsively, is in fact about the best of the lot. Its upholstery is nearly new, the fan is quiet (other booths have fans that clatter), and the clock on the main departure board is visible. On my third visit, the phone center customer rep behind the desk asks if she can help me. She has observed my experimental efforts to fit The Valise into one of her phone booths. I explain the problem, probably distractedly, without thinking that countless other portfolios poured countless dimes into her phone center before me. Her name badge declares “SUSAN—MAY I HELP YOU?” in Micro-gramma Bold Extended. The Microgramma font—perfect for, say, a sumo wrestler or a bouncer in a biker bar—is incongruous with her soft voice and demure manners.

“May I?” she asks, and demonstrates how to fold the handles back, ease the top of The Valise into the back corner of the booth, curve the monstrosity just enough to rest a bottom corner on top of the phone, slip one’s person in, and carefully slide the bifold door closed; meanwhile pressing the bottom of The Valise into the hinge corner, so it stays diagonally in the top third of the booth, out of the way, adequately supported yet protected from the outside world. She steps out of the booth and hands me back my career in cowhide. I feel like an unsuspecting participant in a clown act.

“Try it,” she says with a glimmer of a smile, but not a trace of irony. She had listened to my explanation of the problem so patiently, even though she had seen it all before! I do try it, and amazingly, it works. With The Valise thus suspended above me, I settle into cold calling.

Dan Small is no longer at the number I have for him. I also learn that the number I have for Papillion is actually that of his traffic manager, whose job is to protect her boss and his department from a flood of wannabes like me. Gottschall, I am told with the great cordiality afforded card-carrying, unemployed AIGA members, sees portfolios on Tuesdays and Fridays, and can see me at 10:30 a.m., three Tuesdays hence.

Having transcribed some of the more promising want ads onto three-by-five cards, I begin calling. Susan Microgramma passes by while I am on the phone. She does not wave, but she does gesture ever so slightly with her nose at my suspended portfolio; her look seems to say, “Others made it through here, you can too.”

Somehow, I expected my arrival to have more impact. But the city sees ambitious kids wash up on its shores like so many pebbles and shells. Train ticket filling up with punches, pockets filled with index cards, I work the want ads, most of which turn out to be from employment agencies. I begin to place great hopes on my scheduled appointment with Ed Gottschall.

Answering help-wanted ads does not vary much. One is expected to wait a lot, fill out forms a lot, and smile through utterly impersonal treatment. None of the employment agencies even wants to look at The Great Midwest Mounted Valise!

The Valise Goes Awol

After three weeks of answering want ads and researching design firms I have wrangled an appointment—a real appointment—with an art director who is looking for design help and has agreed to review my portfolio. This may be my ticket out of the phone booth at Penn Station! I take the bus there, a bit euphoric.

Sixth Avenue, somewhere around 34th Street. I am frozen stock still, perhaps 12 inches from the brass door pull at the location of my appointment. Seeing my hand reach for the door brings about the realization that my other hand, which should be gripping my portfolio case, is empty. I have left my graphic design portfolio on the New York City bus that brought me here. My body is paralyzed because my mind is sprinting, darting from realization to conclusion.

If I were in Cleveland, I could go to the Transit Authority lost and found and probably get my portfolio back tomorrow. The New York Transit Authority may have a lost and found, but I know instinctively my portfolio will never get there. Without my portfolio I will never get a job.

After an eternal instant, I am able to move my eyes in the direction of traffic. There are several buses that might be the one I rode, now a few blocks away, merging with other buses into the immense river of Manhattan traffic.

The word “portfolio” means different things in different professions. For an investment manager, it is a selection of investment positions representing ideas about what will succeed at a particular price and time. For insurance companies, it may mean a pool of risks being underwritten. For people outside the creative arts, it is hard to understand the young designer’s attachment to his portfolio. In many professions, the newly educated practitioner passes tests and gains a license. The license means they are like their peers, having a certified professional status. Singers and actors must pass through the fiery furnace of auditions, but at least their talent resides within them. Graphic design is different. You may have a degree from Mount Olympus University, but if your portfolio sucks, your credentials don’t mean much. You may have no education at all, but if your portfolio is exceptional, well, come right on in! Of course, if your portfolio is exceptionally missing, you are really and truly naked.

My mind races to the inevitable conclusion: that Valise is my future. My body takes up the sprint. I cover the first block in a single step. The light at 35th Street is against me, but traffic is immaterial. Screech! Honk! Keep accelerating. 36th Street. I am wearing the Sunday-school clothing of a Presbyterian kid from Ohio: a blue worsted wool suit, black wingtip shoes with soles well worn but uppers buffed. The pain of sprinting in dress shoes is unable to make its way up my spine, drowned by the flood of adrenaline rushing downward. 37th Street melts behind me. If only my high school coach could see this performance! The street sign for 40th Street looms and disappears. I make the first quarter mile in what seems like 15 seconds. Twenty numbered streets to the mile in New York City. I am running after a group of identical buses. 41st Street. For an instant, my resolve weakens. I have, somewhere in my mother’s basement in Ohio, a set of slides of my portfolio. I could forget about it and reconstruct The Valise.

But the danger and the oxygen have me thinking clearly: C-prints from those slides would be of disappointing quality, and it would cost a lot! Find overdrive and catch that bus!

42nd Street is a torrent of traffic. I pick up a bruise on the bumper of some vehicle. I play chicken with a bicycle messenger breathing through the police whistle in his mouth. I have no idea how I am going to recognize the bus I was on, but I will only have to worry about that if I am not killed by a cabbie. Running full tilt, yet drifting back in time, I’m searching for an answer. How long have I been building up my dependence on this bundle of paper? When did it start? Surely I was not born with one? I look back to interviewing for my first job in Pittsburgh, to assembling my college portfolio, then to the portfolio I carried to get into college. Running, I think back further, to Avant Garde magazine and emulating the paintings of Dalí.

From somewhere in the cosmos, help arrives: there is road construction uptown, and a couple of lanes are blocked. I pull even with a half-dozen buses and slow to a trot. Bingo! I recognize the graffiti on the advertising placard on the side of my bus. It is at a slow roll. I bang on the side of the door. The driver does not stop, but opens the door; I catch the grab bar and swing on board. She clearly has not read the transit authority safety rules!

“I thought we would see you!” she says cheerfully. “Behind my seat. You run good!” I seize The Valise, thank her, and jump off; she never slows her pace.

I have to figure out what to do. Clearly, visiting the art director in the thirties is out of the question. I would be an hour late by the time I made it back there. I’ll dream up an excuse tomorrow in Booth 6. My next appointment is (Aha, I have not lost my prized three-by-five cards!) Ed Gottschall, at AIGA. I’m a twenty-minute walk from 63rd Street and Third Avenue, and I am due to see him in an hour. I sit on a bench, my pulse returning to normal. I am now the owner of The Great Midwest Mounted Dumpster. Its contents are scrambled; all the careful mounting and sequencing is askew. Whoever gave it to the bus driver must have pawed through it first—maybe looking for money? Worse, there are large gaps between the soles and the uppers of my wingtips, and they are scuffed and scraped. I am sweaty, and my suit is decidedly grotty. There is a rip in the pant leg where I grazed a bumper. I decide to push on. Maybe there’s a men’s room in the lobby of AIGA.

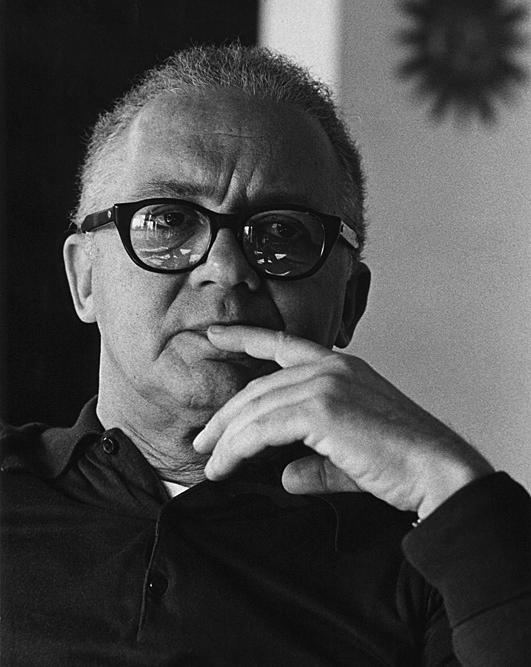

Ed Gottschall: Not Your Average Interview

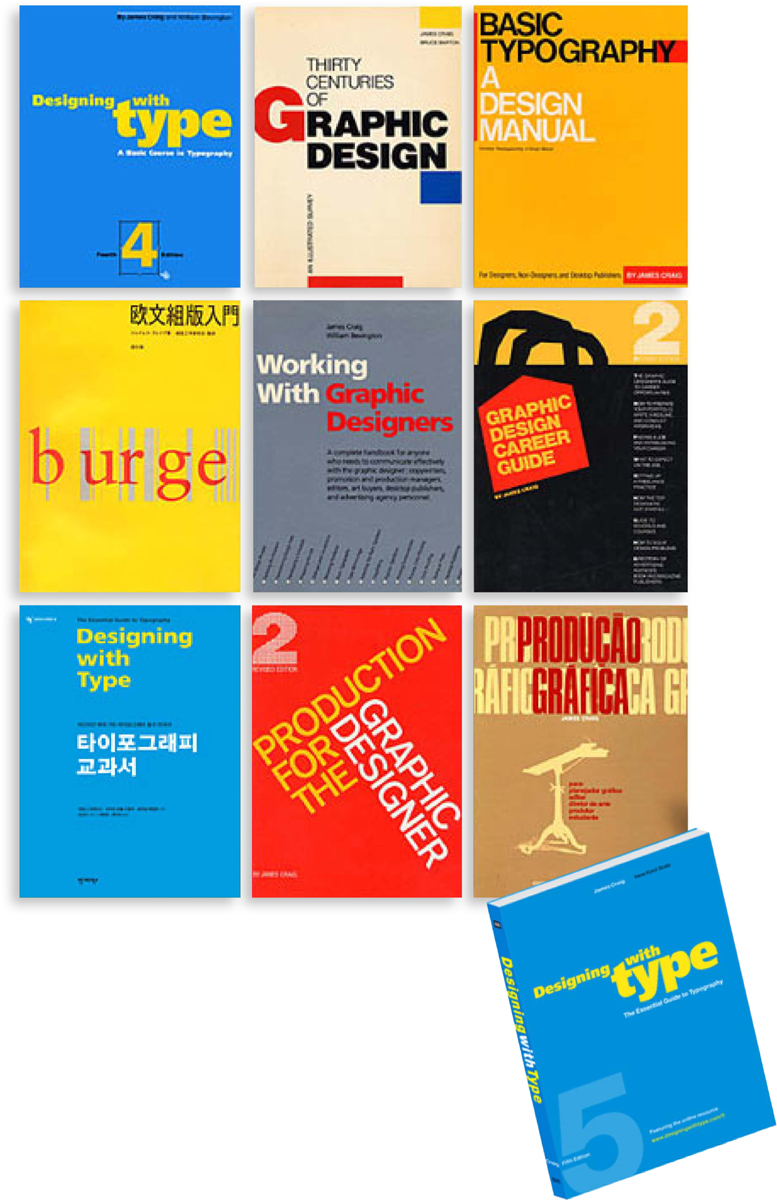

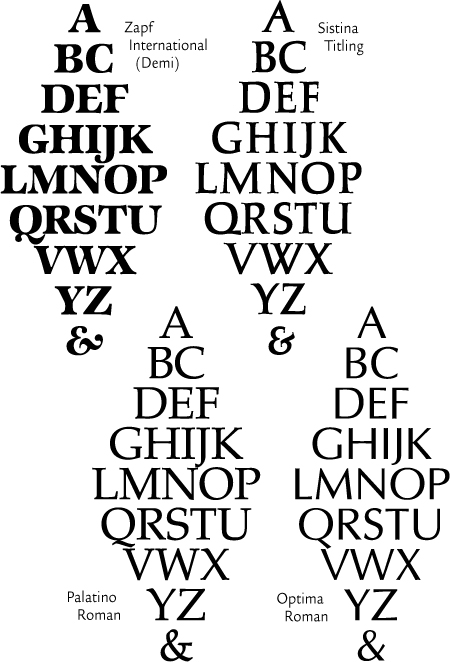

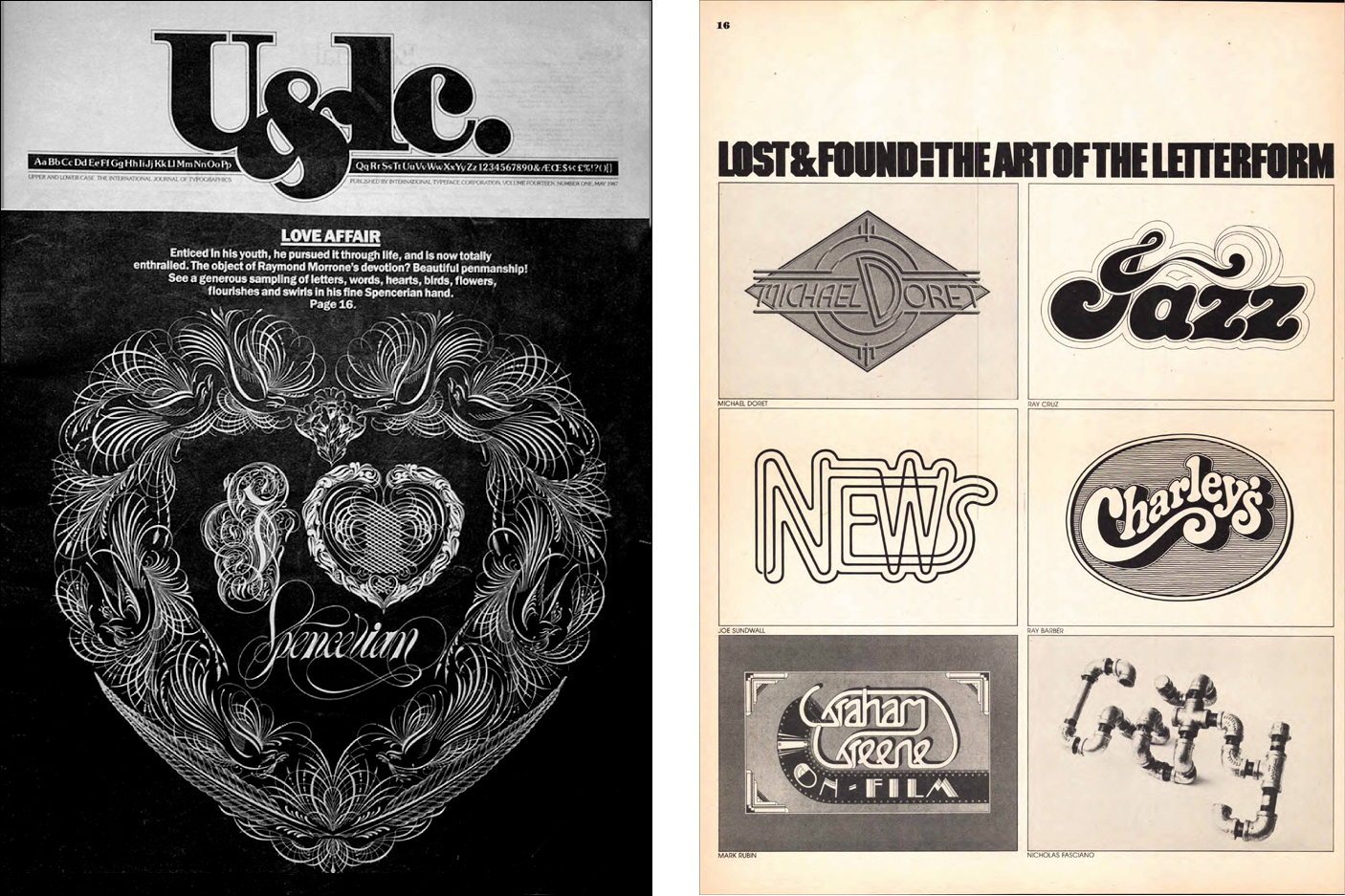

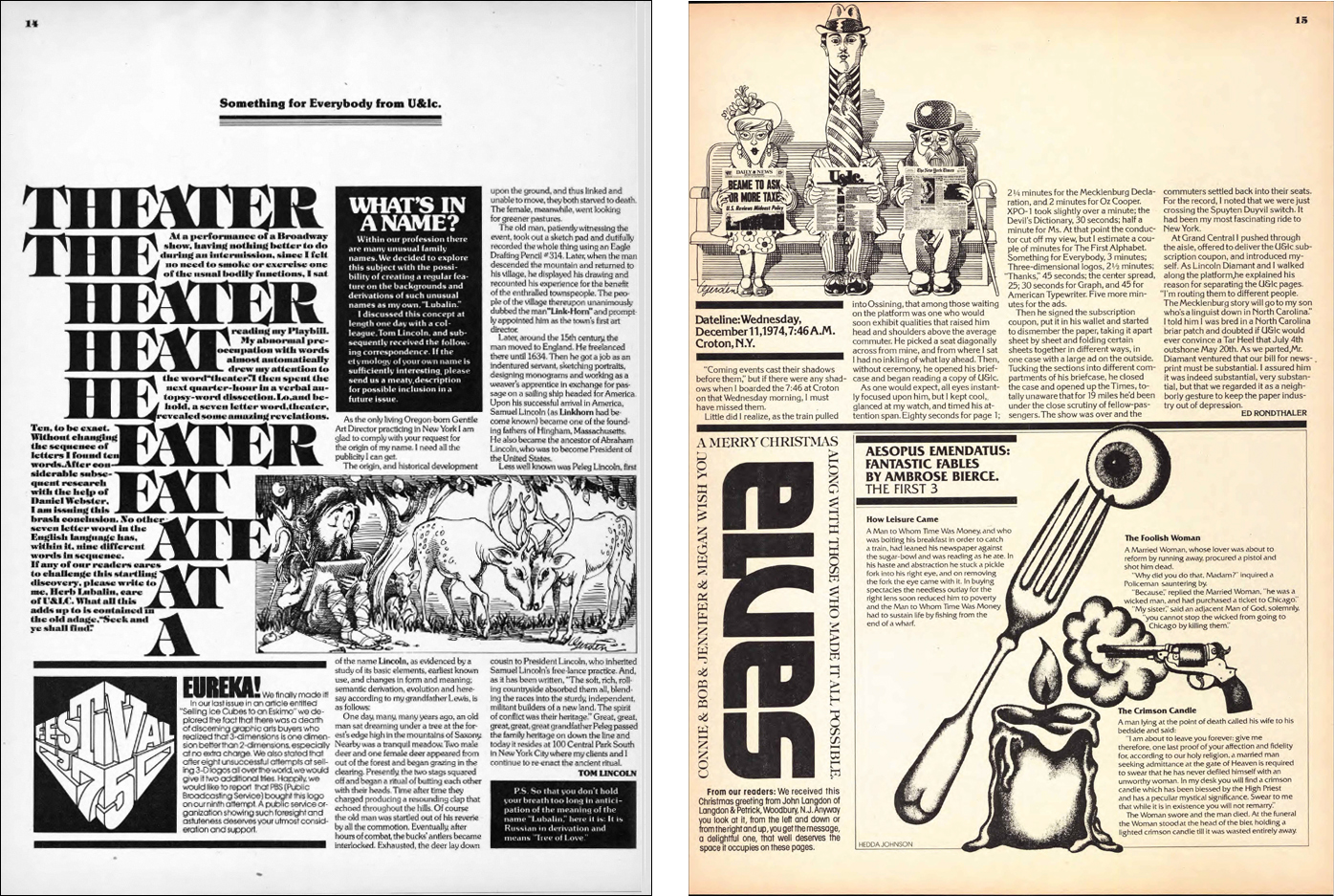

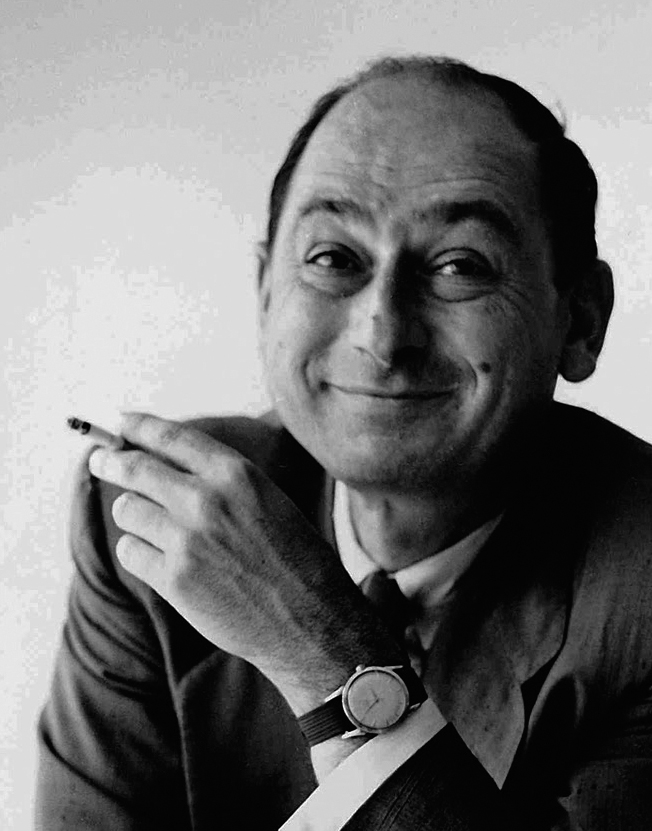

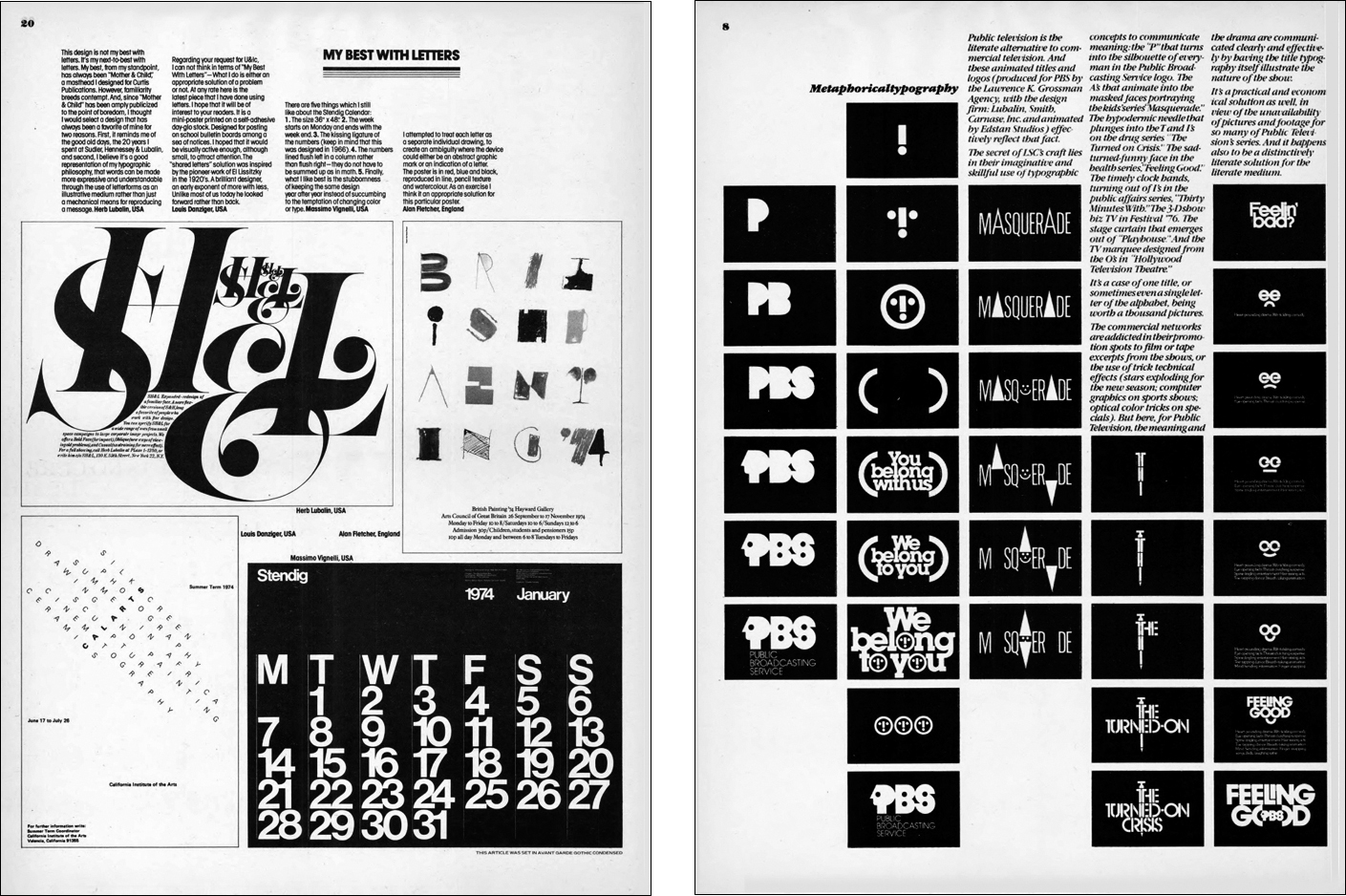

Edward Gottschall (1916– ) is a lifelong enthusiast in typography and design. He graduated from the City University of New York in 1937, and received a master’s degree from the Columbia School of Journalism in 1938. He served as editor of Art Direction magazine from 1969 to 1975 and executive director of AIGA from 1973 to 1976. Gottschall served for two years as president of the Type Directors Club, founding the TDC annual show, one of the longest-running exhibitions in the graphic design world. He was executive vice president of International Typeface Corporation for fifteen years, and served as senior editor of U&lc magazine, an experimental typography magazine founded by Herb Lubalin. Gottschall taught at New York University and Pratt Institute, retiring in 1990. He is the author of Typographic Communications Today, and coauthor of 18 other books.

June 1974

There is not, it turns out, a men’s room in the lobby of the AIGA offices. I arrive at the reception desk still sweaty, but cold. In the shiny door of the elevator, I see reflected a parody of a stereotype: a Midwestern stripling who got rolled in the Bowery. If they laugh out loud, it will be entirely understandable!

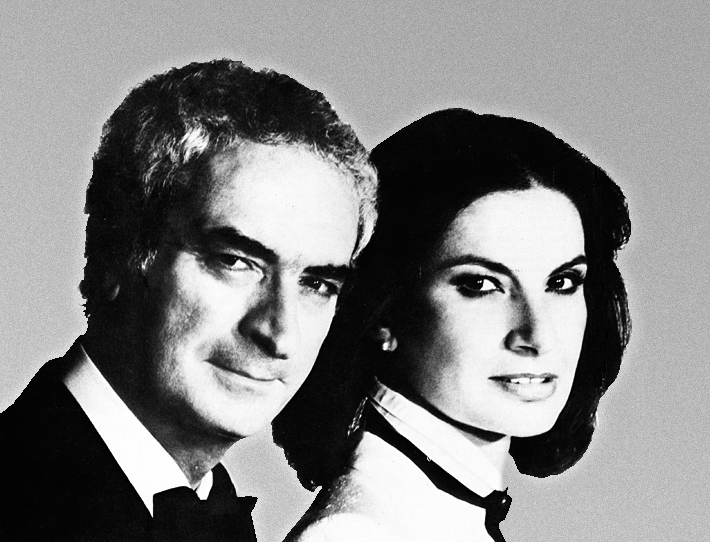

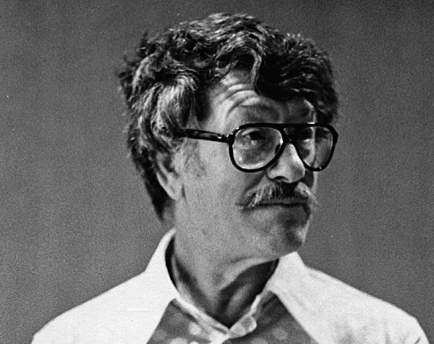

Ed Gottschall is a cordial, dark-haired man. He clearly loves people. I consider explaining my appearance and scrambled portfolio, but cannot begin. He does not bat an eye; in fact, he is incredibly gracious. He rotates each upside-down piece carefully and asks about it. He takes a full twenty minutes to go through The Valise, possibly a record.

“So, David, what are you in New York to do? Oh, book publishing, excellent. That I can help you with.” He reaches across his desk to one of four large rotary address files and starts browsing. “Anyone in particular you want to see?”

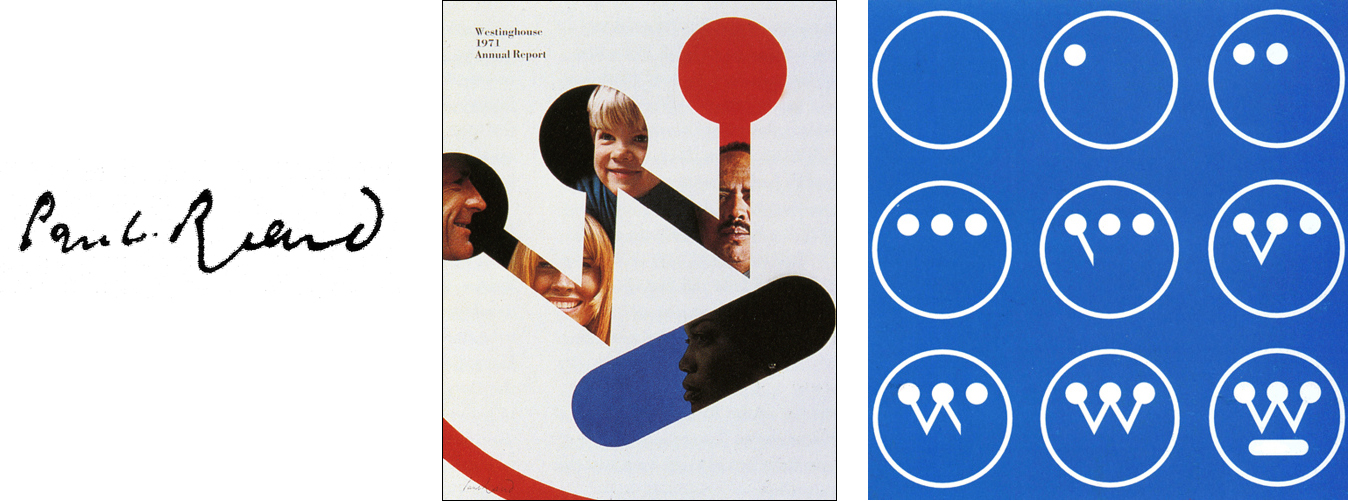

I name some names: Glaser, Chwast, Rand, Lubalin. Never mind that I am naming the most sought-after names in graphic design, Gottschall knows them and their dues pay his salary, so he figures out ways to be valuable to them all.

“Paul Rand’s phone is unlisted, and he says he doesn’t see portfolios anymore, but I know he does—just don’t tell him where you got his number. You may get lucky.”

I feel as though I’ve used up all the luck—bad and good—allocated to me for the decade. He is writing on a yellow pad, line after line, single-spaced. Name, company, phone, sometimes an asterisk.

He explains, “These are the publishers that care most about design—many don’t, you know. Whole art departments without a single AIGA member!” He rolls his eyes with a smile, without interrupting his writing. “Now mind, you can use my name with the ones with asterisks. You will get their gatekeepers, but you mention my name in the same breath as your own. If they don’t call you back, I want to hear about it. I send them business, I send them talent—they should know the score.”

Gottschall gets to the last line of the page, pauses to reread, adds another asterisk, and tears off the sheet. “Son, you have a ton of talent. You stick at it—you will have a great job. But mind, the town is crawling with talent. Where you are in your career right now, two years out of school, you have a lot of competition. Talent is a given; the jobs go to the persistent. Be charming, but by Jove don’t stop calling till they say yes!”

He continues, “You have a right to ask for referrals. Everyone will say they aren’t hiring—even if they’re desperate to fill a job. If they don’t ask how much money you want, don’t bring it up. But you should have your price in mind and say it without hesitating. Figure what you need to live and double it. They will beat you up on price, so have something to give up.” His advice is not exactly new, but there is sincerity and gnosis about him that makes him sound like the oracle at Delphi. He is about to hand me off to his receptionist, when I spot a page on his desk. It looks like an illustration made out of typography. I am unable to pass it by.

“You have talent, and you also have a lot of competition. Talent is a given; the good jobs go to the persistent. Be charming, but don’t stop calling till they see you.”

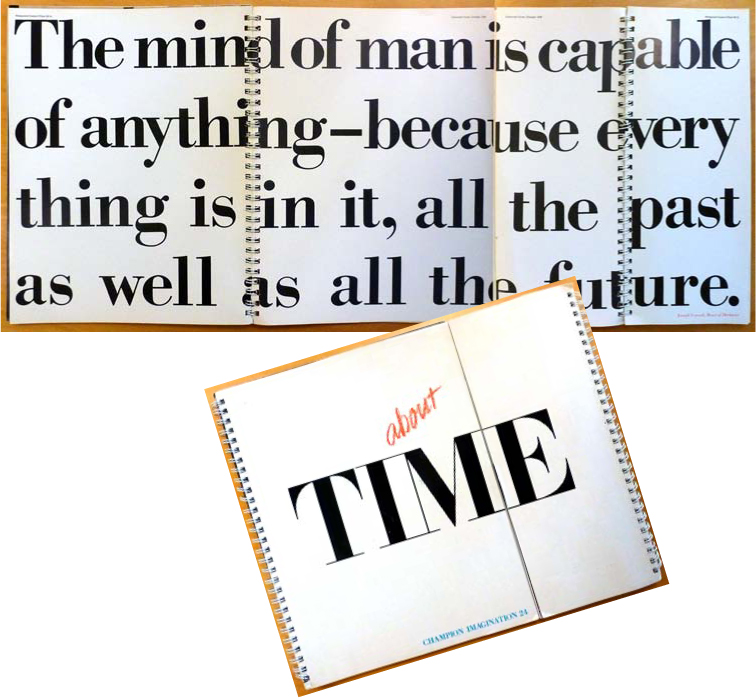

“Mr. Gottschall, what is this?” I have just hit the mother lode.

“Oh, Gottschall is working on a book about typography,” he says, as though he were talking about the inexplicable activities of a crazy uncle. His excitement for the project is impossible to contain. “Been working on it for some time.”

I am wowed, so I act wowed. “What’s the title? Where did you get all these fantastic examples? This wonderful old wood type? These old cigar box tops?” He’s delighted to talk about it; I am making his pet project come alive. A good 45 minutes later, he has given me a short course on typography, and in the process he has been reminded of all the people he knows who love books and typography. I now have a second sheet of names and asterisks, better than the first. My AIGA dues have delivered a jackpot payoff—just because I asked about something interesting on his desk!

A good interviewer will zero in on the faults of a portfolio and rank the talent by lowest common denominator. A really skilled interviewer sees past the faults, and looks at the potential.

I learn two things of great value: First, a good interviewer will zero in on the faults of a portfolio and rank the talent by lowest common denominator. A really skilled interviewer sees past the faults, and looks at the potential. If a kid shows up in tattered clothing with a ransacked portfolio, look at it carefully; you might see something really good that everyone else misses. I am fated to forget and relearn this valuable lesson numerous times. Second, when you finally get in someone’s door, you are getting a glimpse of their life and their interests. It is the mirror image of my first interview with Jim Burke—there he saw something in my portfolio that sparked the interest. Here, I found it on Gottschall’s desk.

Gottschall’s two pages of names become my treasure map and talisman. As I leave his office he says, “Now, don’t be a stranger. I want to know where you land!” What a great expression! It frames job hunting as a flight, as a trajectory. A newcomer to any profession can easily liken job hunting to being earthbound, stuck in the mud. Gottschall says, in effect, “You are a bird on the wing surveying the professional landscape—enjoy the view!” The value of this analogy comes back later, when I am employed and exploration is difficult.

Cold Calling 101

I hear from other designers that Herb Lubalin has a stable of talent with whom he works steadily, and though it’s well known that he never hires green talent, every art and design student who comes to New York wants to interview there.

Sitting in my office in Penn Station Booth 6, I make the first of many calls to Lubalin’s office. The secretary tells me—in what is really a very humane voice considering how many times she must have had to recite her speech—that he is not seeing portfolios or hiring. When I sat in Ed Gottschall’s office that first day at AIGA and he told me to be persistent, I imagined having to call back three or four times. I invest a call to Lubalin, Smith, and Carnase every few weeks. Lubalin’s receptionist learns my name, so I think I am making progress, but after a while she leaves and is replaced by someone new.

As the summer wears on, my book begins to feel tired. Really I am getting tired of showing it and getting praise and referrals but no job offers. I find odd freelance projects, which are not much use for demonstrating my value to the larger marketplace, but at least provide sustenance. I take the train into town and dutifully sit in my Penn Station office with a pack of notecards. I am now polished at hearing “no” and asking for ideas, names, and referrals, so that I always have new three-by-five cards and new names to call. Hope. Each card is scrap of hope. I am burnished by each indignity. Interviewers stand me up. At first I am angered, but no longer—next time I call they apologize and agree to see me. Rarely do they brush off the same person twice.

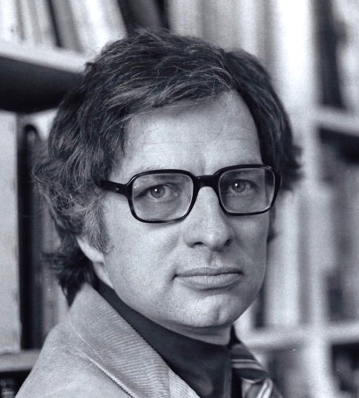

Herb Stern: The One Week Hence Test

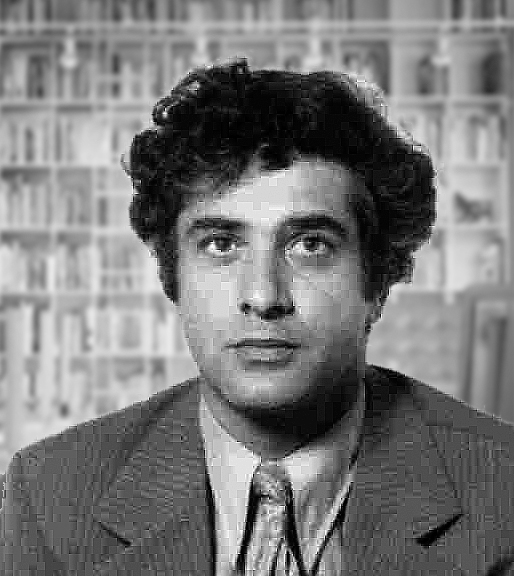

Herb Stern (1930– ) was born in Frankfurt am Main. His family left Nazi Germany in 1938, relocating to New York City. Despite a fascination for art, Stern attended Bronx Science High School, and later studied Advertising Art at the Insititute for Applied Arts and Sciences, New York. Stern began his professional career at J.D. Tarcher & Co., working for Harry Pritchett, a talented art director who had worked with Paul Rand and Lou Dorfsman. The Tarcher agency folded while Stern was in the Marine Corps during the Korean War. Upon returning to civilian life, he worked at the William Weintraub Agency under Paul Rand, and then at Mel Richman Studios. He also had his own studio, serving mainly magazine publishers, before joining Ziff-Davis, where he stayed for thirty years. During that time, he rose from art director to VP Creative, and played a pivotal role in the company’s transition from magazines to technology and media. He retired from Ziff-Davis in 1999, and continues his work as a fine artist.

September 1974

Two hours a day on the train gives me a lot of time to read. George, Be Careful is the autobiography of George Lois, a brash and highly successful advertising art director. Lois describes his process of interviewing new creative talent. Sure, they have a great portfolio, but which ones can think on their feet? Lois devises tricks to startle his job applicants. He will pick up a glass ashtray and toss it at his unsuspecting applicant. If the applicant catches it, that’s a good sign. “Good hands!” A missed catch usually means broken glass. How does the interviewee react? Poised and snappy, well, OK, maybe the candidate is still worthy of consideration. If the reaction is embarrassment or anger, game over.

I begin to think about the interview process from the other side. What are the tests likely to be? What do I need to do to pass them? Suddenly I realize that I’m already being tested. Several people have taken my call, heard my pitch, and responded, “Sure, I’ll look at your book. Call me one week from today, at this exact time, and I’ll set up an appointment.” Up until now, I had noted it on the prospect’s card, figuring that I’d call them later. Nothing magic about that exact time—unless this is a test. I put down the book and flip through my index cards. I realize I have failed the test several times already.

An art director named Herb Stern, I notice, asked me to call back at 10:30 a.m., and today is the day! I make it to Penn Station and call, just a minute or two early. He picks up the phone. I remind him of his interest in seeing me if I called back. He says, “Sure, come in next Tuesday at 4:00.”

Tuesday arrives, and so do I. Between George Lois and Herb Stern, I have learned a new trick, and I vow I will be on the lookout for ways to pass tests with every phone call.

Stern is visible in the design community as the promotions designer for the magazines published by Ziff-Davis. He is a dapper fellow, with hair that lays down straight across the top of his head then erupts in curls at the side. Ziff-Davis is a crisp, professional place and Stern’s office is spartan, almost unnaturally neat. Stern looks at me intently, but the effect is not uncomfortable.

The One Week Hence Test: “Sure, I’ll look at your book. Call me one week from today, at this exact time, and I’ll set up an appointment.”

By this time I’ve learned that, as much as I want to control the interview, things work better if I sit back and let the interviewer go through the portfolio. I hand it over. He flips through it without a word, giving each item about two seconds. Then he looks at the resume, again a fast scan. He reviews the book again at about half speed, putting clips on three or four pages. It’s not uncommon for art directors to keep copies of a few pages of each book they see, so I feel honored when he hands the pieces he wants copied to an assistant. I don’t remember seeing anyone scan the book once fast, then a second time slowly. He turns his attention to me. He asks a few questions about the production details on a few of my designs: what font here, who printed that, who is the photographer, and so on. Those hurdles cleared, he asks about my career goals. I tell him publishing is the reason I’m moving to New York.

Stern raises an eyebrow. “Really.”

I’ve already learned that publishing is not the best-paid field, nor necessarily the place to win the most awards. You go into publishing because you believe in it. He turns to me more directly in his seat and relaxes a bit.

“All right, then, I’ll make a few suggestions.” He goes through my book, removing half the work. “You need not show more than ten pieces.” He continues with barely a pause. “Next, let me comment on your presentation. You kept your mouth shut while I was looking at the work. That’s uncommon for a designer your age.” I flash back to how many times I motormouthed my way through a portfolio showing. I manage to say thank you.

He asks if I have any questions, and I ask whether he is hiring anyone at my level anytime soon. He acknowledges the question with a nod, but continues his advice.

He is not hurrying, but neither is there a wasted word. “You should be here to interview me, too, you know. You should ask what we do, what we look for in new hires. You made it in here, so you have earned the right to ask for names. You should not leave without having harvested at least three leads. Ask, ‘Would you mind suggesting some other shops where you think my work would be well received?’ That way, you’re asking your contact to call your work to mind, and match it with the work of other employers with whom they have personal connections. Always ask for permission to use the contact’s name when you call.”

Stern is paying me a high compliment, coaching me like a rookie coming to the show. His voice takes on a serious tone. “You know why I asked you about production details?” I decide not to wing it, and confess I don’t know. He continues, “There are always young designers who want to break into the business so much that they slide a few pieces of finished work by other designers into their own books. They don’t realize that an experienced art director picks it up right away; so the questions about things like fonts and production are a sanity check, a way to see if the portfolio you are seeing is for real.”

The One Week Hence Test: “It’s an employer’s survival skill. Ninety percent of the first calls can’t make that second call. I don’t want disorganized help, no matter how great a portfolio they may have!”

I like this guy—he’s got one trick after another—so I hazard a question. “You asked me to call you back exactly a week later. Was that some kind of a test?”

He replies, “Perhaps. Really, it’s an employer’s survival skill. Ninety percent of the first calls can’t make that second call. I don’t want disorganized help, no matter how great a portfolio they may have!”

“I can’t make time to train you, but I want you to keep in touch, and send me new samples.” He scribbles several names on the back of his card, shakes my hand, and with his left hand he gives me the card.

To show I have been listening, I say, “May I use your name?” He nods, and at the same instant his assistant appears to show me out. He is already turning away to review his phone messages, and in seconds I am back on the chaotic Manhattan pavement. I send Stern an occasional note or sample, but the opportunity to work for him does not materialize. Yet his coaching quickly becomes a permanent part of my self-presentation.

Seymour Chwast: Bad Luck, So Good Luck!

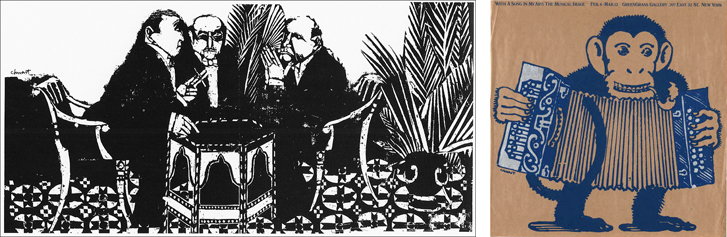

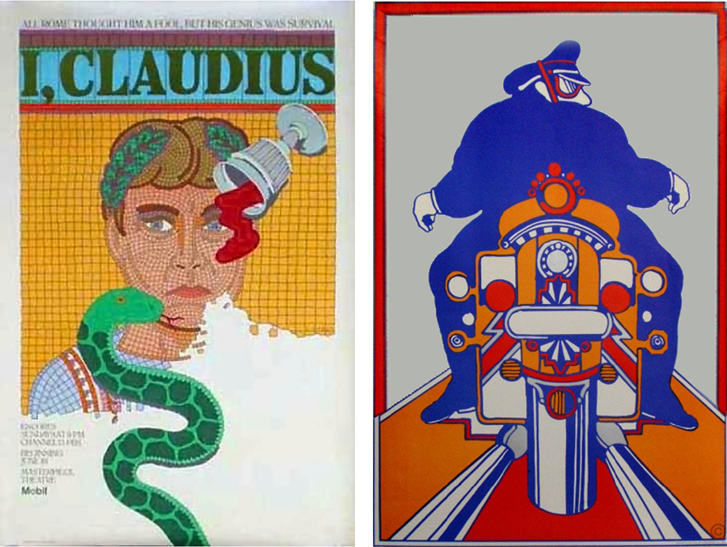

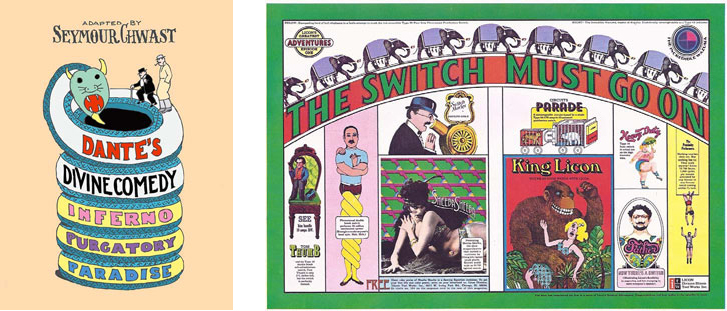

Seymour Chwast (1931– ) was born in the Bronx, New York, and educated at Cooper Union. After an early attempt at setting up a studio with his fellow students failed, Chwast worked at the New York Times promotion department, followed later by Esquire magazine and Condé Nast. He began soliciting freelance work with some fellow designers by publishing Push Pin Almanack, which showcased creative illustrations. (It was later renamed Push Pin Graphic.)

Push Pin Studios did for the graphic design what the electric guitar did for music. Their work seemed to proclaim “We are for pure, joyful expression: decorative, rich, inconsistent, polyglot, and exuberant! Design and illustration are inseparable, and by the way we can originate the font and write the headline if we feel like it. We can do anything for anybody; we can invent three new styles every day before breakfast!”

Chwast’s versatility in drawing, design, and typography, along with the fruits of his collaborative work with more than two dozen other Push Pin members, was honored with a retrospective exhibition at the Louvre. In 1984 Chwast was inducted into the Art Directors Club Hall of Fame; he was named an AIGA Medalist in 1985. He is the illustrator and originator of many books, including illustrated versions of Homer’s Odyssey, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, and Dante’s Divine Comedy.

October 1974

Twelve weeks and counting since I stormed Manhattan, and still no job. I train into Penn Station, check the want ads, make phone calls, and shuffle through my three-by-five cards to see whom to call when.

I try to schedule portfolio showings in the morning, pick up the odd freelance job, grab an early afternoon train out of the city to beat rush hour, then finish my freelance work in the wee hours. It has the regimentation of a job, but without the regular pay. The Presbyterian Sunday-school outfit gives way to a commuter’s shirt and tie. The intensity of work on new portfolio pieces tapers off. I am getting interviews, but no job appears. My new shoes—bought to replace the ones ruined chasing buses—look very worn. The Great Midwest Mounted Valise, purchased when my savings were ample and my optimism high, looks weary too. Discouragement is setting in, and I have to find ways to fight it.

What got me here was enthusiasm for big design, Push Pin, Chermayeff, Rand, and Lubalin, but none of them are interviewing. Sifting through my cards, I come across Push Pin Studios. I have calls logged weekly for the first ten weeks, then a gap. They have a receptionist, and she has a waiting list: you leave your name once and she confirms you are still on it, but they are not setting appointments. Someone is peering in the phone booth door at me, so I had better make a call. Push Pin it is.

“Push Pin Studios,” says a new voice, and hope stirs. Remember to smile before speaking.

“Hi, this is David Laufer. I’m on the waiting list to show my design portfolio.”

“I don’t see you, when did you call?” A nice voice.

“I called first in May, and have been calling on and off since . . .”

“Oh yes, I see you. You requested Mr. Glaser. He is still booked, but I just had a call canceling a morning meeting with Mr. Chwast. Can you be here in thirty minutes?”

What a combination of great luck and rotten luck. In my exhaustion from the previous night, I hadn’t rearranged or refreshed my portfolio, and I would have liked to refresh my memory on Chwast’s career and work. I have barely enough time to get there. An unhappy commuter mutters at me while I extricate The Valise from the phone booth and dash across Penn Station for the southbound subway. I stop in the men’s room. I look crummy! I splash my face with cold water. The paper towel dispenser is empty, so I dry off with toilet paper from a stall and scram.

The office is not glitzy, but it certainly is busy. There are several rows of cubicles, the surfaces of which are covered with reference material, clippings, sketches, and photos. There are a half-dozen large, black portfolios similar to mine, leaning up against the side of a cubicle. Are these other applicants’ work? I look closely, and see that the luggage tag has a Push Pin business card in it. Even the most published studio in the world has several portfolios ready to show to customers!

I announce myself to the receptionist, who appears to be marking up a large manuscript and monitoring a lot of packages coming and going. The workspace seems smaller than my expectation, but the atmospheric energy is immediate.

“Mr. Chwast says he will be with you in just a few minutes.

” The reception area is full of envelopes and boxes waiting to be picked up by couriers, and there is a table for inbound packages. I recognize the labels of several typesetters.

The receptionist motions me into a cubicle. After a few seconds I realize this is not a spare cubicle—this is Chwast’s workspace. It is crowded but orderly. There are project files laid out in envelopes, and a side table with markers, brushes, half a dozen swatch books for colored paper, film, and inks. These are the usual art supplies that I and everyone else have available, and yet what world-changing work has come from them.

“Hi. Seymour Chwast,” he introduces himself, extending his hand for a friendly shake. I’ve seen pictures of this man in magazines, smiling with his latest creation, holding this award or that. In person, he has a quiet demeanor. He has an air of mystery, which may be a result of my admiration for him, but I think it is real.

“Keep your seat. Give me just a minute,” he says, moving purposefully through the files on his desk. A young man with sandy hair dashes in with an illustration and pulls back the flap. Chwast locks his gaze on it. Without taking his eyes away, his fingers pop off a few strips of masking tape, and he attaches a piece of tracing paper on top of the illustration. I can’t see it well, but it’s a line illustration in gray, with the white areas filled in with flat areas of colored film, like pieces of stained glass shining around the metal frame. After lifting the tracing paper to view the work, he lays the paper back down and circles selected areas, then hands it back.

Chwast turns to me. Someone with that many projects in front of him should be stressed, but he seems quite relaxed. His manner is at once smiling and serious.

“Do we have a resume from you?”

I probably sent one a few months back, but I reach in the back pocket of The Valise for one. Nada. I have a stack of them sitting at home, but The Valise has none.

“I am really sorry, I appear to have given out my last one—I will have to send you one. This appointment came open just today...”

I am feeling worse by the second, but Chwast is cheerful and unfazed.

“Sure, send one on. Not important really.” He waves away the unimportant resume. “We use them to write notes on, is all,” he says as he finds a legal pad and pen. “So, let’s see your book!”

Here is a man who has probably seen thousands of portfolios, probably does not need to ever look at another one in his life, yet not only is he willing to see a drop-in, he still takes pleasure in the activity! He flips through the work quickly. My portfolio is loaded with watercolors and sketches as well as my finished work from Pittsburgh, and it is a bit of a hodgepodge. It does not look considered or organized, and I am cursing myself for not being better prepared. Note to self: Every day is your big chance!

In my mind I hear Herb Stern whisper, “Don’t apologize. Just let him see what interests him.”

Some interviewers engage their interviewee in small talk: where are you from, who have you been to see, how did you get my name. Chwast focuses intently on the work on his first pass through it, which takes perhaps 45 seconds. On his second pass, he makes a few comments without looking up.

“You draw well, but the mood of your work is very dark.” He is reacting to the watercolors I made of a series of urban scenes, influenced by my commuting. “There is a place in illustration for every mood, but sunshine sells better. Your industrial experience—where did you work?”

“Pittsburgh.” I give him a quick verbal resume. I am struggling to be cheerful and fighting the feeling that I have wasted the long-hoped-for opportunity of this meeting with this creative legend.

Chwast says, “When you draw for yourself, you can of course bring out your innermost feelings. When you draw for others, you must find expression for theirs.” He is looking intently at me now. He is addressing me not as a student or a street kid, but as a peer.

I see in an instant that the intensity and authenticity of his illustrations are a natural extension of his personality, his disposition.

“You can draw anything you perceive, you convince me of that. Now convince me you can draw someone else’s point of view.”

“There are a lot of times that we as hired guns have to feel an emotion or take a position that is not ours. I see here the work of a soul confronting raw truth with clear eyes. Not easy. You can draw anything you perceive, you convince me of that. Now convince me that you can draw someone else’s point of view.”

I don’t have a good response. He is right. I feel bleak, and my work shows it. I am not sure why I came; maybe I should go back to Ohio. I hope I am not looking like I feel.

Then Chwast’s voice dispels the cloud. “I want you to do something for me—well, for yourself really.”

“Sure!”

Chwast picks up the steam engine, drawn with a compass and ruling pen. It is the same one Jim Burke liked. I keep it in my portfolio even though it is student work. Superstition, I suppose. Chwast holds it in both hands with a bit of ceremony and puts it in my hands.

“Go to your studio, and make a dozen new works that are not steam engines, but that have the same joy and simplicity and wit that are lurking here.” He pauses to see my reaction. “I’m serious now—you have the skills to make this portfolio much more exciting, and the faster you prove it to yourself the more use you will be to the this community.”

The sandy-haired man ducks back in with the corrected illustration. Chwast looks at it quickly. He removes the tracing paper. He makes a circular motion with his index finger over one area and says, “This area needs another layer of yellow, then flap it and it can go back to Forbes.”

I have recovered my wits a bit and am able to remember some of the work of his that I especially admire. I ask him how he uses so many different media—most illustrators find a medium they like and beome expert at it. Chwast seems to be the master of a dozen.

“Oh, speed, you know, we have to produce so fast, we are always looking for ways to get the right emotion on the page quickly.” He talks about moving from wet media to flat, colored adhesive film, and then on to other media experiments, but it’s clear he is less interested in media and more in the emotional effects he can get across. A phone call breaks in. Cradling the phone in one hand and shaking my hand with the other, he summarizes, as if stating a homily, “The perceptions of the people who buy what we sell are more important than the truth. So—good luck!” There is an elfish animation in his face as he says it, but I know he is earnest about his encouragement.

“The perceptions of the people who buy what we sell are more important than the truth.”

I can’t help but wish I had I been better prepared for this meeting, but perhaps we get what we need. I make my rounds and head home to New Brunswick, New Jersey with the conviction that my portfolio needs a makeover, and Seymour Chwast has given me a powerful insight into how to do it. He has also added some clues to the art versus design dichotomy: something to do with expressing your feelings versus intuiting the feelings of others.

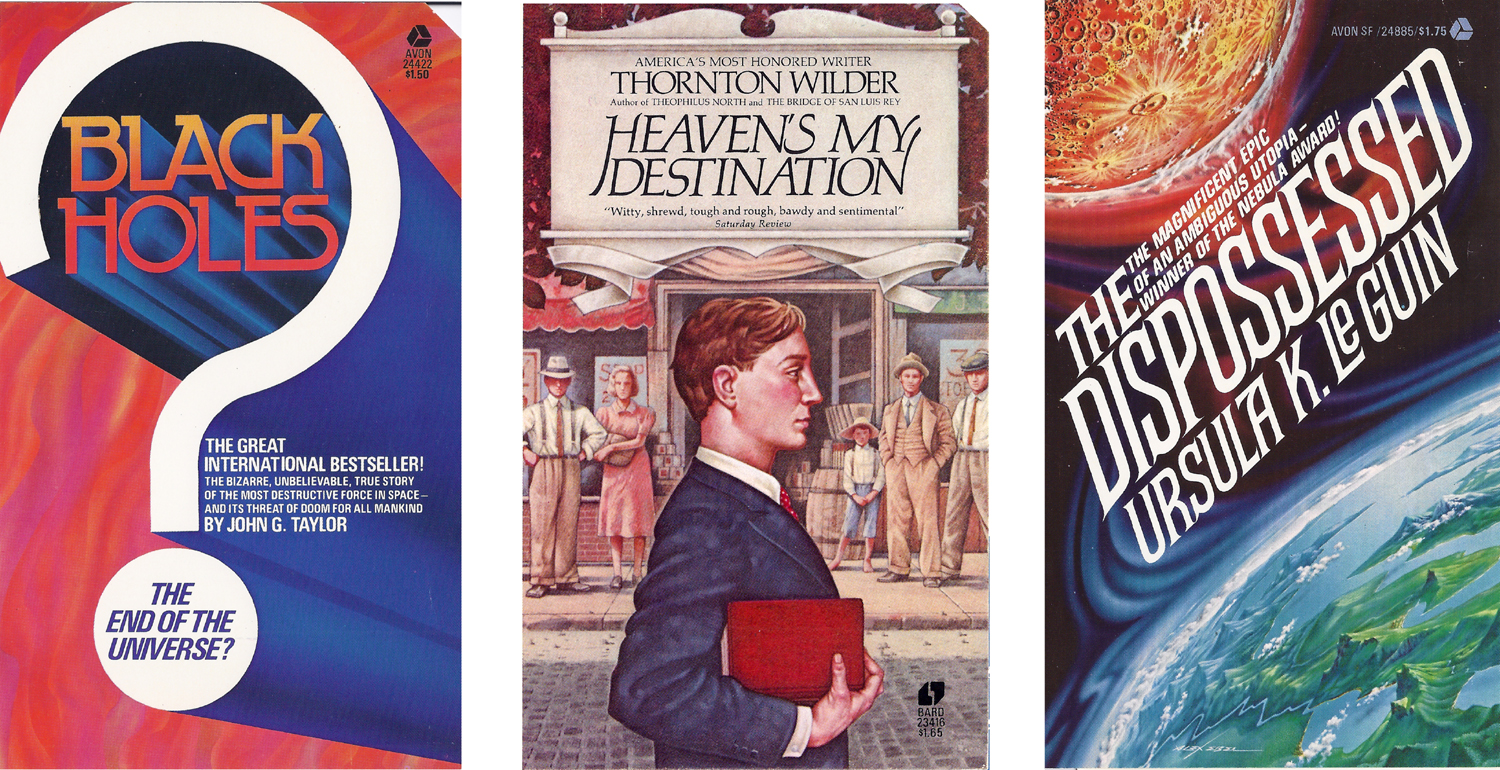

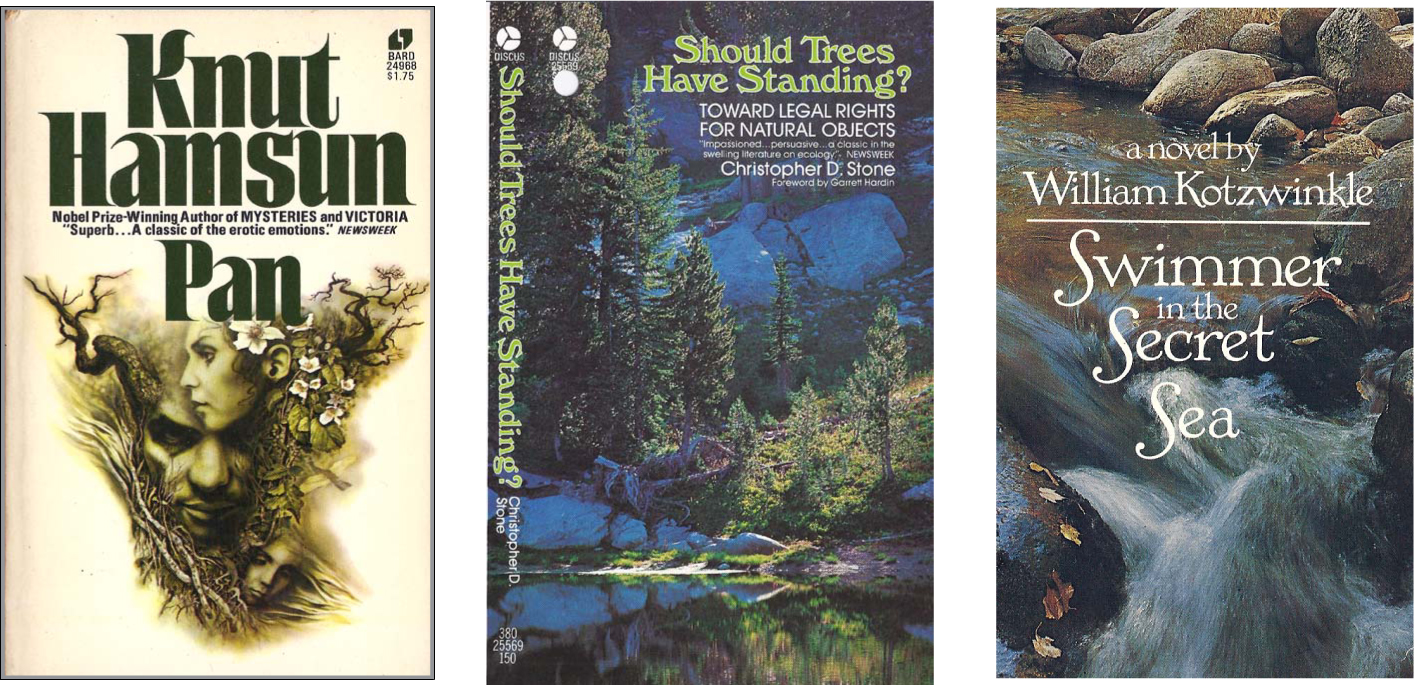

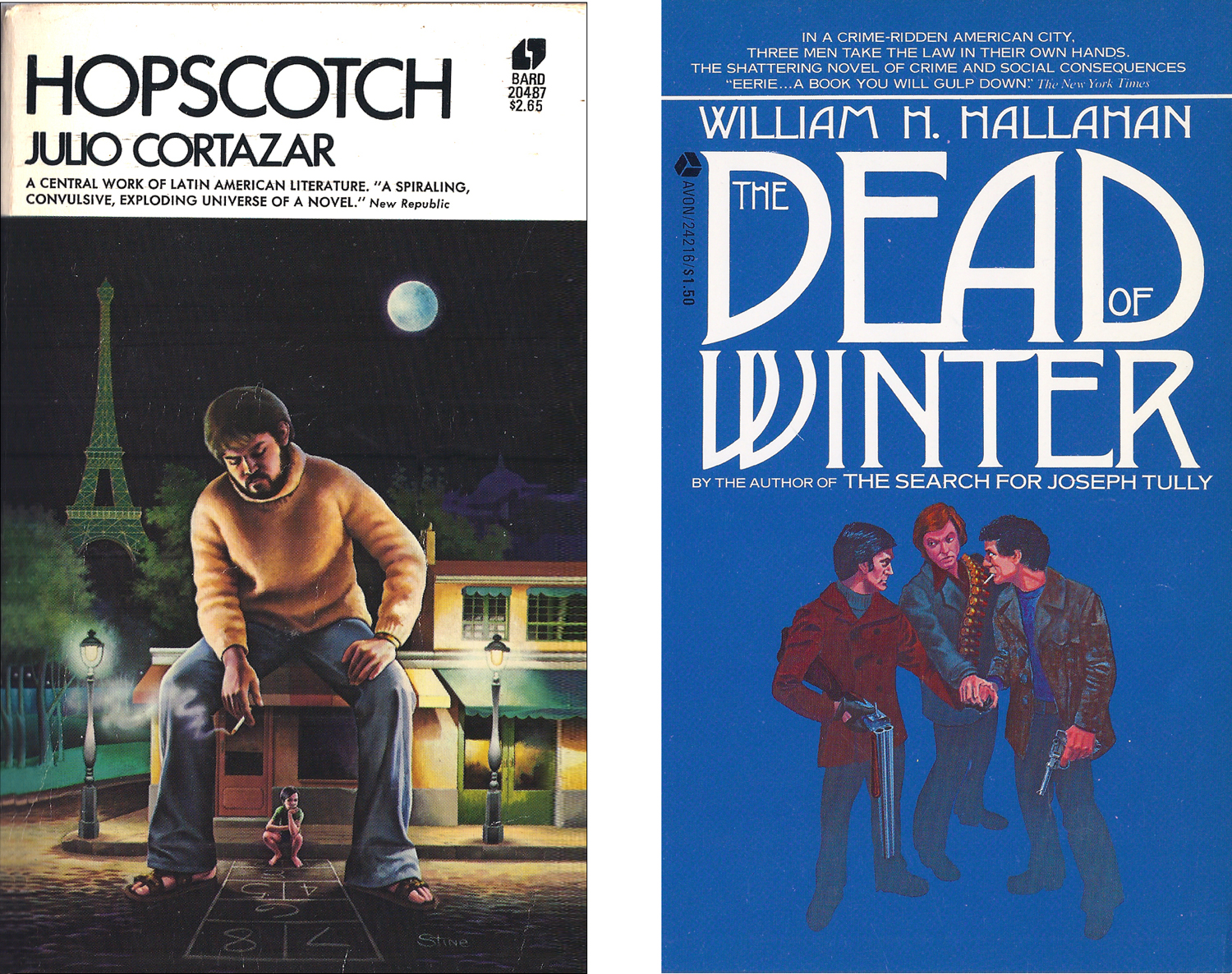

Ian Ballantine: A Short Course in Genre Publishing

Ian Ballantine (1916–1995) was active as a publisher for his entire career. He attended Columbia College and the London School of Economics. He wrote his thesis on paperback book publishing. He brought Penguin Books to the US. Ballantine and his wife, Betty, were part of a team that founded Bantam Books in 1945. In 1952 they established Ballantine Books, which they sold to Random House in 1973. The Ballantines continued as freelance editors and consultants to many publishers. They are most famous for their commitment to promoting science fiction as a literary genre. Their numerous awards include two World Fantasy Awards, in 1975 and 1984. Ballantine published the first authorized paperback edition of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, the H.P. Lovecraft series, and more than 160 titles on World War II. All told the Ballantine publication list is more than three thousand titiles.

October 1974

Interviewing involves a lot of waiting. Not infrequently I arrive for an interview only to be told that my interviewer is in a meeting, out for the day, has been called away, might be back in an hour. I note these things on my cards. I develop the habit of carrying a book with me to read while waiting. I happen to be reading Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy the day I am to interview with Ian Sommers, the art director for Ballantine Books.

“Let me see if I can find Mr. Sommers,” says the receptionist.

So, I open Asimov and, within a few sentences, am engrossed in a world far away.

“So, you are reading Asimov!”

The voice comes to me through a thick acoustical shield necessary for reading against a noisy environment. I have never met Ian Sommers, so I assume this must be him, coming to look at my work. I stand, and instinctively grasp for The Valise.

“You are young to be an Asimov reader. How did you get interested in him?”

“I—to be honest, I had heard of him, but didn’t know what to expect. I was intrigued by the illustration on the cover. I needed something to read for the train. I had no idea what I might be falling into.”

This answer pleases the gentleman and his smile broadens. “A lot of thought goes into those covers.” I am a bit confused, because he makes no move to lead me anywhere. I decide to relax a bit and put down The Valise. “He is one of our best authors—very fast, very deep.”

I have to hold up my end of this conversation. I sense that some sort of testing is going on, but different than that of Herb Stern, since I am already in the door. My interviewer knows about book jackets. I am interested in them too, so I go there. “The jacket of this edition did not prepare me for the seriousness of the subject. I thought it would be—”

“Oh, you are getting at the heart of the publisher’s problem! How to make a sale with very limited information, very little time. There is no way to give the reader a full description of the narrative. We seize upon style, color, writing, typography, symbolism—absolutely anything we can use to get to the right emotional place instantly. The jacket has to be a window into the author’s soul. So what made you decide to buy it?”

I consider. “It wasn’t so much the investment of money as the investment of time, for me.” I remember Heinz Edelmann talking about hooking the prospective buyer with curiosity.

“Yes, you are not alone there. We have to constantly look for a way to convince the reader that they will have a good read—that they will want to stick with it to the end.”

I look at the cover again. “I think it was the unusual color scheme—it piqued my curiosity.”

“Yes! Asimov is profound, but at bottom he is optimistic about humanity. We work to package him that way.”

I need more information about where this is going, but I am not sure how to steer it. I gesture toward The Valise. “As a graphic designer, I am especially interested in those types of cues. I hate to quit a book in the middle, and I hate to invest time finishing something that isn’t interesting. I feel an obligation to help people select what they will like and avoid what they won’t like.”

This apparently is a good thing to say. He begins walking, saying, “Let me show you.” We enter a smallish conference room with bookshelves across the long wall. All the books are paperbacks. Some of the books are turned spine out; others are displayed face out, in layers, the way they appear in racks in stores.

“The heart of the publisher’s problem: How to make a sale with limited information, very little time, and lots of distractions. We seize anything to get the reader to the right emotional place instantly. Design is like a window into the author’s soul.”

“Each cover is a little poster,” he says. He is animated, glad, perhaps, to have an audience for an evolving theory. “You have only the top three and a half inches to catch someone’s eye. Title, colors, maybe a bit of the illustration.

So your first job as a graphic designer is to get the browser interested enough to give it a little attention, to pick up the book out of the rack.”

This is a bit of a revelation. Even though I’ve lingered over paperbacks frequently, I have never thought to break down my decision-making process and apply it to my graphic design work.

I say, “So that is why titles are always at the top.”

He looks at me carefully. “We’re experimenting with that. With some genres we think we get more handling with only a picture visible at the top.”

“Genres,” I repeat, curious. “You mean like poetry, biography, reference?” I am parroting the categories of publishing from the Literary Market Place.

“Oh no, much more specific than that.” He hands me a book. “You know the book Jane Eyre?”

I read Jane Eyre in high school and have forgotten all but the flavor of it. “Of course,” I answer, a little confused because the book he hands me appears to be some sort of period romance, but the title is not Jane Eyre and the author is not Brontë.

“Hugely popular, so much so that publishers wish they had a dozen Jane Eyres every year.” I look at the cover more carefully. There is a woman in a white nightgown trimmed with lace, her long, dark hair somewhat disheveled, running toward the reader, away from a large mansion, English—maybe eighteenth century. It is night in the illustration; the sky is deep blue, mysterious with brooding clouds. The mansion has a tower with a window high up, glowing dimly yellow. Is there a figure in the window, or is it a ghost? A flame? The story of Jane Eyre comes back to me. I look up at him.

“So this is like a Jane Eyre sequel?”

“A Jane Eyre industry! The cover of a gothic novel is a formula. It tells a certain reader what type of story to expect. If I put no light in the window, nobody buys it. Yellow is hope. If I put a man with the woman, it means she finds tempestuous love. If the man is chasing her, that means one type of plot. If he is running with her, the story is more about their struggle to be together. If the man’s hands are touching her below the neck, then a handsome but mysterious stranger ravishes her. Of course, they both turn out to be royalty.”

I am astounded.

He is telling me that there is a very specific set of cues that publishers use and that regular readers understand. “We know—after a lot of false starts—how to satisfy the many types of readers who want romance.”

“The gothic novel.” I repeat seriously. “That’s what you mean by a genre?”

“This is how we solve the problem of helping the reader choose what they will like. Of course, it’s constantly evolving.” He hands me another book. “Western genre. You see? Indians in this one.”

He hands me more books. I hold half a dozen until I have to start putting them on the table to receive the next example.

“Here, weapons and a hangman’s noose in a tree. Western lovers know that this plot has struggle, killing, heroism, but no romance. Here, spaghetti western-type plot. Here, more romance, less gun fighting. Here, the townspeople struggle against landowners and East Coast bankers. Townspeople win, of course.”

He’s very serious, so I hazard a joke. “That’s why it’s called fiction?”

He makes a knowing gesture, something like a wink and nod.

“Now science fiction—completely new challenges here. So many types of writing, so many types of readers. Not as predictable as romance readers. That’s why I was interested in why you bought your Asimov. Some readers like formulaic science fiction with hordes of little green men invading, being beaten back by plucky human heroes. Some want to be whisked away to other planets with fantastic machines. Your Asimov there, much too deep to be reduced to a formula. He defines new genres; other people copy his successes. But we are finding some cover imagery to help the buyer find their way.”

The receptionist pokes her head in the door.

“Are you Mr. Laufer? Mr. Sommers says he has been held up at a photo shoot and can’t make it back to see you. He asked me to make an appointment for next week.”

I manage to reply, “Ah, OK, I will see you on my way out.” In confusion I turn to my companion. “Sorry, I thought you were Ian Sommers.” The spell has been broken, my lesson in the art of genre paperbacks ends abruptly.

“No, I should have introduced myself. I am Ian Ballantine. Pleasure to talk with you. I’ll tell Ian we spoke.” He is gone. The receptionist books me next week with Ian Sommers, and I am back on the street. I am never to see Ian Ballantine again, but he has given me a crucial scrap of publishing education at a crucial time, helping me think and speak like a publishing insider.

Good packaging transcends decoration and sets an expectation that is consistent with what the product can deliver. A package both explains what is for sale and is part of the value of the item being purchased. In the case of cultural products—books, music, motion pictures, games, and so forth—the design challenge is to convey a highly nuanced idea of the cultural experience on offer. This requires an ability to empathize with many types of audiences. Modern cultural packaging can be traced to theater and circus posters of the 19th century; it developed into highly differentiated graphic languages in the 20th century. While genre marketing risks confining the appeal of a product that might otherwise find a wider audience, it can also be highly effective in cultivating a loyal audience.

Aha: Only in an economy where the consumer faces a staggering range of choice is graphic design a crucial service. Design is not just making things look good, it is making things look like what they really are, so that choosing and using are in harmony.

In college, it was fashionable to be suspicious of the dominant paradigm. Capitalism seems manipulative, controlling. And there are some people—capitalist or no—who do try to manipulate markets, to limit the choices, or to keep prices in their favor. But there are also capitalists whose success rests on their ability to see what people want, to differentiate slight variations in customer preferences, and to experiment until there is a profitable relationship. Ballantine’s intense curiosity about the fiction reader adds a nuance to the design definition. Graphic design is rarely about selling people a product they don’t want. It’s about helping people avoid what they don’t want and clearly presenting what’s offered. This means developing a dialogue with the marketplace, so that buyers can distinguish, from among too many choices, the things they do want.

After talking with Ballantine, I tinker with my definitions. Design is the science of understanding how humans make choices. Art describes the consequences of our choices and perhaps lets us glimpse the choices we never made. I am not sure Ballantine would agree with this—we discussed nothing about art—but I find myself thinking that graphic design is largely unnecessary in an economy of scarcity. Only in an economy where the citizen/consumer faces staggering choice is graphic design a crucial service. Graphic design—all design really—is about making things look like what they are, so that choosing and using are in harmony.

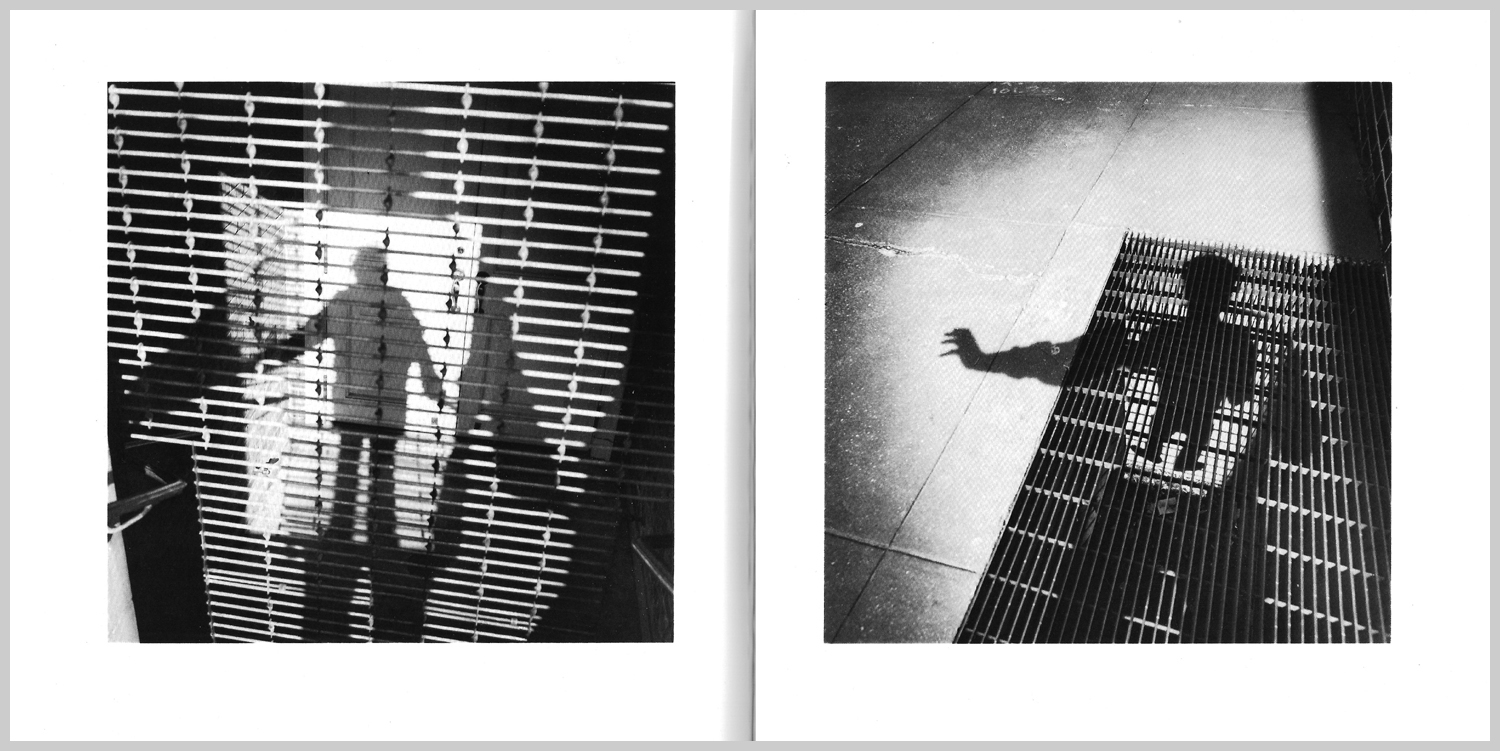

Singing to The Gatekeepers

October 1974

Eighteen weeks in, interviewing has bogged down to a slow grind. Working from Penn Station Booth 6, I can reach out to perhaps two dozen people a day. I get more interviews than I did in July, because I have more names to drop when I call, but things are still not working right. I take on some modest freelance projects that I execute in the evening so I can make calls and go to interviews during business hours.

After my chance meeting with Ian Ballantine, I have a new appreciation for paperbacks, and I begin to work my way through the Literary Market Place (LMP) list of art directors for paperback publishers. There are paperbacks on sale everywhere. I browse their covers in Penn Station. Bantam Books has the most consistently provocative covers. LMP lists Len Leone as the art director. I mail a few carefully chosen samples, and, of course, call his office and leave messages—trying a few days, skipping a few days, trying again. This goes on throughout September. I try various tactics so the receptionist remembers me.

She answers Leone’s line with his extension number. “3313,” she says. I decide she is probably a nice person, but saying that number a thousand times a week makes personalization impossible. I jot down my different lines each time I try one. They fill three cards, then four.

“Calling for Mr. Leone.”

“David Laufer for Mr. Leone.”

“David Laufer, graphic designer, freelance or staff.” On and on.

She usually says, “Thanks, Mr. Laufer, may I take your number for Len?” After a while it becomes, “Thanks, Mr. Laufer, I have your number from yesterday.”

Finally I try something new. She answers, “3313.”

“Hi, is this 3313?” I ask, grinning.

She chuckles in spite of herself and says, “No, this is 2698, can’t you hear?” Then I say my name. Variations of this game go on for a week. I try singing the number back to her using different tunes. Then, one day when I have dreamed up a clever new variation, I get:

“Leone here.”

Rarely have I been so unprepared for success. I have to stumble through a sentence about who I am and why he should see my portfolio. He is incredibly smooth, even cordial.

“Yes, David, I have the samples you sent. Very nice work. Forgive me for not calling you back. Since the Macmillan bloodbath I’ve had calls from more experienced talent than I can see. But I heard Barbara Bertoli is looking for someone; do you have her number?” This is the first time I have heard “Bertoli” pronounced by someone who knows her (BEAR-toll-ee), but I manage to remember that she is Leone’s counterpart at Avon Books.

The shock of getting through to Leone causes me to dump my address cards on the floor of Booth 6. Leone reads Bertoli’s number and I write it on the back of my hand. I will probably never get another shot, so I go for the throat.

“Mr. Leone, you’re the king of book jacket art directors, and you need to see my portfolio.”

He doesn’t disagree, but he doesn’t lower the drawbridge either. “Well, in normal times it would be a pleasure—call Barbara, and if that doesn’t work out, keep us on your list.”

“What’s the Macmillan bloodbath?” I venture.

“Oh, Macmillan laid off most of their art department. Rumor was they were trying to unionize—close to two hundred people I think.” His voice has a remarkable quality of caring, calm, assurance, and relaxed sincerity. “Early June. I knew some of them, and, you know, we try to help as many as we can.”

“Mr. Leone, I admire your work—I especially liked The Sleeping Murders—and I can’t thank you enough for your time.”

“Sure, David, good luck.”

Aha! His gatekeeper is away for just an instant, and I reach The Man himself—and I have two transcendent pieces of information. First, the reason it feels as though I’m swimming against a torrent is that I am swimming against a torrent! The week before I arrive in New York, two hundred competitors begin looking for the same job I want, and they all have experience on their side—not to mention contacts! Somehow I feel much better!

Second, I have a warm lead. There is not a moment to lose, yet I waver, superstitiously looking for just the right dime, a shiny one, to put in the slot.

A Trial Run

“Hi, Ms. BEAR-toll-ee, David Laufer here. Len Leone told me that you were looking for design—”

The effect is magical. I hear her voice smile. “Well, Joe Cool himself sent you! Let’s see,” Bertoli says briskly. “I have an 8:00 a.m. with my publisher. Can you be here at 7:40?”

The power of a name! No need to remind her what I do or that she has been receiving samples from me. Leone sent you, so come right on in.

The 6:02 is on time, and so am I. However, when I arrive at Hearst headquarters, it’s clogged with people. There are several camera crews, and the crowd is bristling with microphones. Randolph Hearst has been in the news for much of the past year since his daughter, Patricia, was taken hostage. Then, the young Ms. Hearst shows up on the news robbing banks with the Symbionese Liberation Army and now has been missing for months. Maybe they found her, or—I hesitate to think of the bad news that could be breaking. A voice reaches me from below the crowd.

“Are you David?”

My eyes travel across the crowd, until I look closer and down.

“Barbara Bertoli.” A tiny woman with dark hair and an exceptionally strong grip shakes my hand. “This way—we can go around the frenzy.” As we circle, I see a silver-haired man, hatless in the cold, speaking into a circle of microphones and lenses, calmly but resolutely giving a statement. “Our owner. Everyone in the company feels so badly for his family,” she says crisply. “His daughter gets kidnapped and they follow him around like he owes them a statement. And he owns newspapers! No professional courtesy.”

Up in the Avon offices, she sets aside her great coat and I see she is even smaller than my first impression, yet her personality fills the room with confidence and purpose. Her office appears quite cramped. Even though there is space for a table and chairs, the room is closed in on every wall with book jackets laid side to side. They are in wire racks, just like those in pharmacies. It’s a laboratory for comparing jackets. Even though my portfolio contains zero book experience, Ian Ballantine’s crash course, obtained by chance just a week before, helps me say the right things. Like the locomotive connection in my interview with Jim Burke, it is just enough of a hook to establish some dialogue. I develop a hunch now that design interviews require, in addition to the basics of being on time, not spilling the coffee, and having a reasonable command of language, a certain serendipity, an unpredictable detail that gives the interviewer a premonition of good chemistry. In neither case, so far, has it been factual—in both cases, it is an emotional bridge. I must work on systematizing and pre-arranging my serendipity!

The Serendipity Theory: successful design interviews require—in addition to being on time and other basics—some unpredictable detail that gives the interviewer a premonition of good chemistry.

Bertoli considers for a moment, then says, “I want you to come in tomorrow and work with us for a day. We’ll see how you apply your thinking.”

The next day, I’m shown to a drawing board that appears to have been salvaged from a Pacific island after an early nuclear test. It’s in a windowless cubicle piled with collapsed cardboard boxes stacked to the ceiling. But it is downright roomy compared with Booth 6, and I am so happy to be actually designing something that I crank out dozens of different jacket comps. One of the four staff designers gives me a clipboard with half a dozen single-page synopses on it. Each one describes a book that Avon has in process, with a modest summary of the plot, key features, genre, audience characteristics, price, sell copy, and awards won.

Across from me, in a slightly roomier cubicle with a window, sits a tall designer with jet-black hair, quite a luxurious black beard, and blazing white teeth smiling out from under a curled moustache. Richard Nebiolo joins Bertoli to look at the pencil tracings I am taping on the cubicle walls. He seems like a giant next to her, but there is no doubt who’s in charge.

Bertoli looks at my work and starts rearranging it. They discuss the merits of different ideas in a jargon I half understand. “This looks like a below-the-line title ...” “Not this, it sends warm and wonderful signals ...” “Too understated, too oriental ...” She stops to consider the first cut.

From under his moustache, Nebiolo smiles with a bit of mischief. “We got to get rid of this kid. He will put the rest of us out of work!” Bertoli spirits a few of my designs away to place on her racks.

Nebiolo says in a low voice, “I told her she is crazy if she doesn’t hire you.”

I am invited back for the rest of the week, but the following Monday I am back in Penn Station while Avon tries out some other designers. I tear into my remaining cards, determined not to sit around waiting for Avon to call.

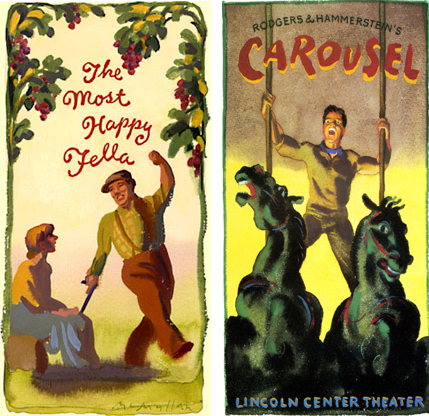

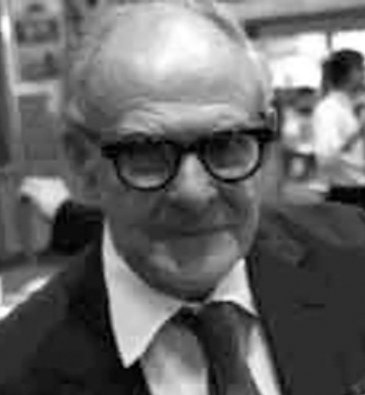

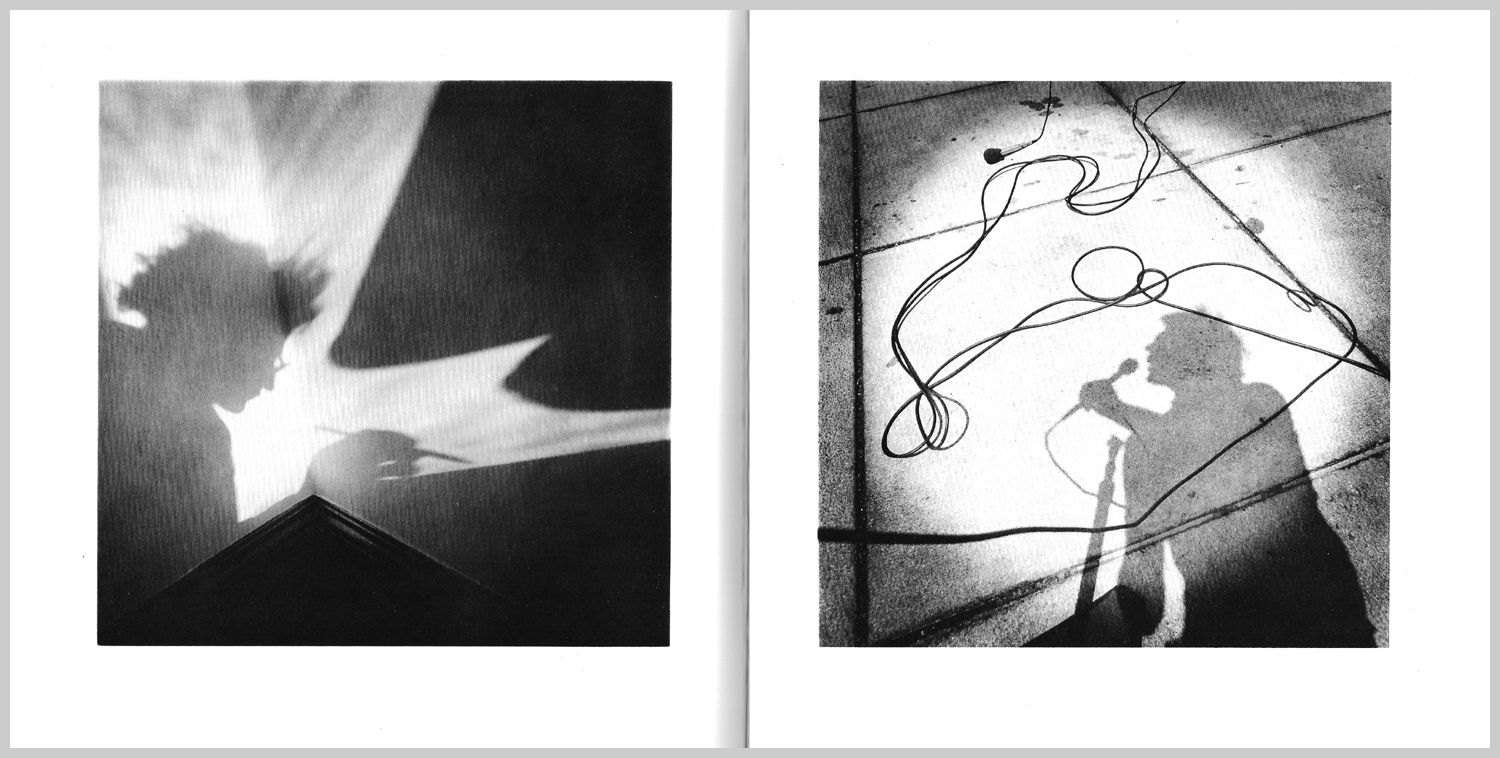

James McMullan: Watercolor Wizard

James McMullan was born in 1934 in Tsingtao, China. He studied at St. Paul’s School in Darjeeling, India, the Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle, and Pratt Institute in New York. McMullan is one of the most accomplished illustrators of his generation, combining a quick conceptual wit with an eye for color, pattern, facial expression, and gesture. His work is all the more remarkable because of his technical mastery of watercolor. He has produced more than fifty theater posters of exceptional quality, which are summarized in his book The Theater Posters of James McMullan. He has also contributed to magazines, books, and annual reports, and won numerous awards, including the Hamilton King Award from the Society of Illustrators.

October 1974

I notice James McMullan’s name among my cards and connect his name with an outpouring of exceptional illustrations I’ve been noticing in the media. I call his number and his assistant books a time for me that same week. I learn later that someone with whom I have interviewed recently sent him my name, though I never learn whom to thank. I’m torn whether to take my design portfolio or bring my paintings. I know I’m not in control of my wet media enough to sell illustration, but I want to paint and I want insight and encouragement. In the end I take two portfolios.

I gaze at the many examples of McMullan’s work in his lobby, and realize that I’ve seen much more of his work without realizing it was his. I remark on this and he pauses momentarily, considering a response.

“You have to respond to the market, of course. I realized early in my career I could do caricatures, and that magazine and newspaper editors always needed them. I like doing more thoughtful, painterly work, so that’s what I advertise—the work you have seen associated with my name.”

I show him some of my urban environment paintings, and we talk about watercolor as a medium. I tell him I find it hard to go from a drawing to watercolor paper because tracing paper leaves marks that show through the finished painting.

“You have to sketch in a medium that dissolves as you paint.” He shows me how he draws an outline of his subject with bright red watercolor in a crowquill pen and then paints right onto it. It explains the little flashes of bright red that appear and disappear like a thread sewn into the fabric of his work.

“Watercolor is a good illustrator’s medium,” McMullan tells me, “because it forces you to work at a furious pace. That suits the furious pace demanded by most clients!”

“What if it gets away from you?” I ask, referring to something that every watercolorist has experienced.

“Well, you do a sketch first. The sketch helps you get your composition, of course, and also helps you to decide in what order you’re going to lay down your washes, and what colors are going to work. Here’s a sketch.”

McMullan shows me an illustration for a caricature of the comedian Don Rickles and the finished work next to it, which was commissioned by New York magazine. It’s amazing how good the first one is; yet the second one, though not greatly different, has clearly benefited from the first.

“Sometimes the first one has more freshness. I’m taking more risk and working alla prima. Sometimes the second works better. I used to do a series, but now ...”

Seeing his sketches next to his finished work is worth a dozen lessons in watercolor. He takes in the two portfolios and nods.

“It’s tough to get started as an illustrator. There are very few places where you can earn a salary to illustrate. And when you find them, they want to control every aspect of your work.”

“I know your dilemma. It’s tough to get started as an illustrator. There are few places where you can earn a salary to illustrate. And when you find them, they want to control every aspect of your work. You have to figure out a way to get your style and your name paired in the minds of the media community. And once it gets popular, people ape your style immediately. You have to be prepared to move on to something new quickly to stay valuable. Now I go after more complex, thoughtful work that’s harder to copy.”

That’s the second time he’s used the word thoughtful to describe his work. I know from experience that interviews as rich and valuable as this one never last long enough, so I decide to be direct.

“Are you looking for an assistant?”

“Yes, always. I get a lot of requests for projects that pay reasonably well and that with some coaching could be done by someone less experienced. The trouble is, they don’t stay long enough to be profitable. Honestly, I think design is your most salable skill. You don’t have to be an illustrator to be creative and influential, you know. A lot of designers can’t draw. A lot of illustrators can’t design. You can be a bridge. Your drawing will serve you well, especially when you’re communicating with illustrators,” he says earnestly.

This short interview helps me tremendously. McMullan, an illustrator’s illustrator, uses a visual analogy—the bridge—to help me decide that I am probably a designer, not an illustrator. I keep drawing, but I begin to focus my portfolio toward design.

Barbara Bertoli: Strong, Yet Vulnerable

November 1974

Richard Nebiolo from Avon Books calls me to tell me how much they can offer me. I know I should negotiate, but it is November 1, five vertiginous months after I arrived in New York. The savings my wife and I brought to New York are all but gone, devoured by 115 round-trip train rides, several thousand pay phone calls, two pairs of Presbyterian dress shoes, and countless three-by-five cards.

I enter a new phase of my career. I am immersed in mass-market, rack-size books. I must see every event, every emotion, every sales pitch in a ![]() ×

× ![]() -inch frame. I quickly realize that my salary covers rent, commuting, tuition, and taxes, but I must do freelance work for food and clothing.

-inch frame. I quickly realize that my salary covers rent, commuting, tuition, and taxes, but I must do freelance work for food and clothing.

Bertoli is very demanding, and she works for editors and a publisher who expect us to perform. A title might cost the company millions of dollars, and a packaging mistake can cause mass marketers to drop it from their coveted rack space—reserved for what they are sure will sell.

When Ian Ballantine described the design of paperback covers, it seemed complex but predictable. Now I’m in the thick of it, evaluating dozens of cues—fonts, colors, illustrations—to communicate with a harried reader who has certain needs and understandings about how their reading material ought to be presented. The jacket designs that Bertoli requests and I sketch are made and remade; sell lines rewritten; many color combinations tried; illustrations bought, modified, repainted, restarted anew. The floors are often littered with scraps and rejects.

Even after the first proof comes back from the printers, modifications continue. Bertoli is self-taught as an art director and has a very open-ended way of working, which at first I find baffling. She often senses where she wants the cover to go, but cannot tell her staff specifically how to fix something.

She says, “This design needs more depth, more atmosphere. But is has an intimate quality I like. Don’t lose the intimacy.”

Or my favorite: “The gothic novel heroine is strong, yet vulnerable. Explain to the illustrator that he needs to discover that essential gothic dichotomy in our heroine.”

All this is to take place in the top half of the book jacket that is visible in the mass-market rack—a space less than 16 square inches!

Nebiolo, with probably ten more years experience than I have, becomes a valuable friend, teaching me shortcuts and introducing me to illustrators who come into the office. His best advice is about negotiating the creative process.

“When Barbara runs out of ideas, she yells. I find what she needs is dialogue. Give her the first wacky idea that comes to your head. She won’t like it, but she will react to it. As long as the finished design sells, the success sticks to you. Be careful about falling in love with your own work. I’m not saying you never get your own ideas approved, but if the team hasn’t seen it, I don’t trust it. Somehow when the group mauls an idea—it breaks the dialogue open and then we discover the essence, the meaning, the indefinable something that makes the product good.”

Nebiolo has a particular talent. He can take the title of a book, choose a font with a certain emotional resonance, and then exaggerate the letters to intensify the emotion. He works the letters in soft lead pencil on tracing paper, working back into the graphite characters with an eraser and a thin metal eraser shield until the grouping of letters has the right emotion. I watch in amazement as, with twenty minutes before a deadline, he lays a piece of treated acetate over his approved pencil drawing and draws the letters using India ink and a brush, then touches up with drafting curves and a technical pen. The result is typography with a special handcrafted quality. When I study the mass-market paperbacks on display in Penn Station, I see Nebiolo’s titles setting Avon apart from the competition in a subtle yet persuasive way.

“I’m not saying you shouldn’t defend your own ideas, but if the team hasn’t mauled it, I don’t trust it. Somehow it breaks the dialogue open and then we discover the indefinable something that makes the product good.”

From the standpoint of hours worked per employee, Avon could easily be categorized as a sweat-shop, but it is the opposite: the atmosphere is so exciting, everyone wants to be there. That excitement emanates from the office of our publisher, Peter Mayer, and flows to every department. In my first weeks at Avon I hear Mayer’s name breathed with the reverence with which the Lost Boys speak of their Peter Pan.

One morning, Bertoli hands me the briefing sheets, including a number of well-known Thornton Wilder books. Mayer likes to publish literature along with bestsellers. He has an eye for literature that can cross over and be big, and he picks up the paperback rights. And Bertoli has developed an eye for which of his pet projects he sees in this way.

I’m a bit intimidated by the assignment. Wilder is in print, so I stop into the public library on my way to Penn Station, pick up four of the Wilder titles in the series, and tear into them. I start to generate some designs and put them on my wall.

Bertoli scans them as she cruises by. “These Thornton Wilder sketches aren’t in below-the-line format.”

The meaning of what she is saying begins to sink in. The below-the-line formats are preapproved and therefore quick to design. I have screwed up, putting more time into them than was needed, and she won’t be able to show them at the meeting.

But then she says, “I like your treatment, though. It’s possible we could publish it outside our established formats.”

“Wilder has personality,” I venture. “I read the books before I started, then while they were fresh in my mind I started designing.”

Bertoli looks at me sharply. “I think you should sit in on the cover meeting and present this series yourself.”

Panic! I am going to have to present my ideas to Mayer, who chews up everything our department does and transmogrifies it. Even his failures work better than many publishers’ successes. The only fortunate thing is that the meeting starts in a few minutes, so my panic has no time to escalate.

Barbara opens the meeting briskly. “I asked David to join us so he could explain his approach to the Wilder titles.”

Mayer looks much different than I imagined. He has a boyish, casual stance and, underneath a head of unruly hair, a gaze so intense that it makes him seem closer to you than he is.

I put up my three series of Wilder titles. Out of terror, I say nothing, which is the perfect thing to do. Bertoli, four senior editors, and Mayer are looking at them carefully.

Paperback book art directors must be versatile, able to find the excitement in a subject and execute it within time, budget, and marketing parameters. Barbara Bertoli did not herself draw or make sketches, rather she used complex, emotional descriptions of the feeling she wanted, and called upon many exceptional illustrators and photographers to interpret her titles.

“David decided Wilder is too important to be lumped in under Bard format...,” she begins for me.

“He has such a unique voice,” I get from somewhere, “and we have four exceptional titles.”

“Six, now,” says Mayer. “Did you study Wilder?” I decide the folks in this room are too smart for me to bullshit.

“I read Our Town in high school, so I knew he was a writer of stature. When Barbara gave me this series, I got them out of the library and read these four. After a few chapters of Theophilus North, I became a fan; after The Eighth Day, a believer!”

Mayer has a dazzling smile, which I see for the first time now directed at Bertoli. “Where did you find a cover designer that likes to read?!” We all know this is unfair—everyone in the department loves reading—so he turns serious again; all eyes are back on the covers.

“So, David, you did three series, and they are different. Before I tell you what I am going to publish, tell me which one you like.” Mayer leads by putting people to the test, and it’s exhilarating.

I decide not to try to guess what he’s planning, so I say a few words about each series, then turn to face to the wall those designs I am not recommending. Bertoli looks on apprehensively. Either Mayer is going to throw them all out and insist on a Bard format, or we are on the verge of a breakthrough.

“Good,” says Mayer, studying them. “It’s a bit risky, but I like the chutzpah. If we play our cards right, it may migrate above the line.” I leave the meeting with a great feeling of accomplishment. In the past, I’ve had trouble explaining and defending my designs in group meetings—I thought I didn’t like being in the spotlight. Here, with the acute interest of our cultural commanding officer—and no chance to prepare my remarks ahead of time—I discover a more intense spotlight, and I am suddenly able to talk about the designs with conviction.

Aha: I didn’t like being in the spotlight. I had trouble defending my designs in group meetings. Here, under the intense spotlight of our cultural commanding officer, I discover that I am suddenly able to talk design with conviction.

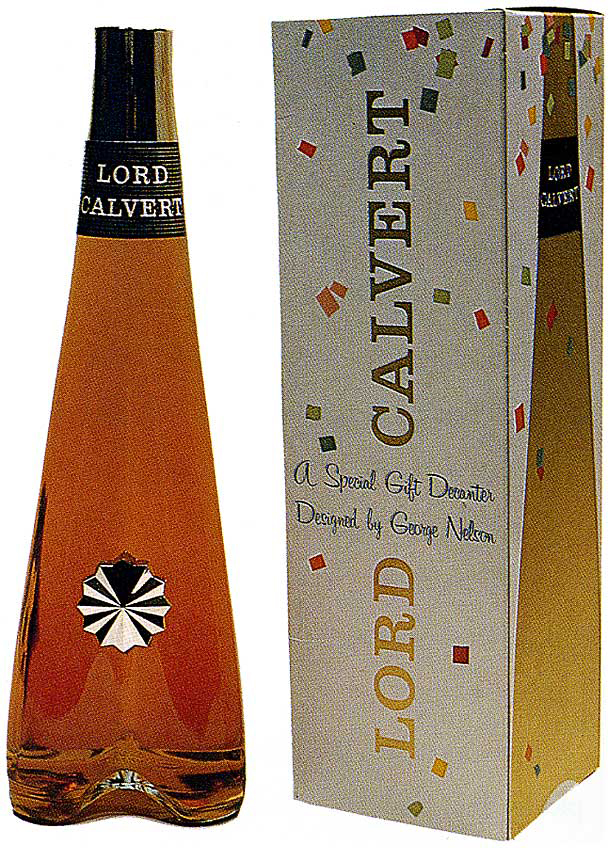

Max Miedinger: Getting Helvetica Right

Max Miedinger (1910–1980) was born in Zurich. He trained as a typesetter and attended evening classes in design and typography at the Kunstgewerbeschule, then went on to set type for the Globus department store in Zurich. His natural affinity for typography led to a position as a sales representative for the Haas’sche Schriftgiesserei, a renowned type foundry near Basel. In 1956, he began an independent consulting career. Miedinger is principally known for creating the Neue Haas Grotesk typeface in 1957; the font was redrawn (with Edouard Hoffmann) and released as Helvetica in 1960. Despite the presence of numerous other sans serif fonts, Helvetica achieved a balance between simplicity and emotional purity that made it a worldwide standard.

February 1975

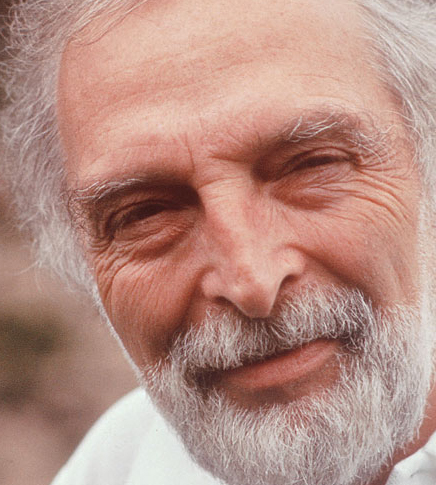

Photo-Lettering, Inc., is a high-end typesetting company. They are the premier repository for unusual fonts, including many exclusives, and their craft is excellent. Their type specimen book is a treasure; they don’t just give it out to anyone. Richard Nebiolo, who learned his craft working at Photo-Lettering, escorts me there on a lunch hour and introduces me to the owner, Ed Rondthaler, whom he describes as “a beautiful person.”

I visit Photo-Lettering several times a month to pick up, drop off, or review work in progress. On one occasion, Rondthaler is just passing the pickup desk. He doesn’t remember my name, but remembers we have met and associates me with Nebiolo.

Rondthaler says, with obvious satisfaction, “Guess who was just here?” and hands me a business card. The finely crafted card says “Max Miedinger.” Below, in Rondthaler’s handwriting, it says “Designer of Helvetica. Visited here,” and today’s date.

Just then, Miedinger himself comes back through the door. He asks Rondthaler if he might have an extra set of Photo-Lettering type books to take back with him. I am holding his business card. While Rondthaler gets the books, I introduce myself and strike up a conversation. Miedinger is a personable, intense little man whose eyes are constantly exploring; he is very taken with Photo-Lettering, and with all things American.

“We designers are sellers of subliminal details that the average viewer does not see, but they do feel. The message is somehow warmer, memorable. That is precisely what gives typography its power.”

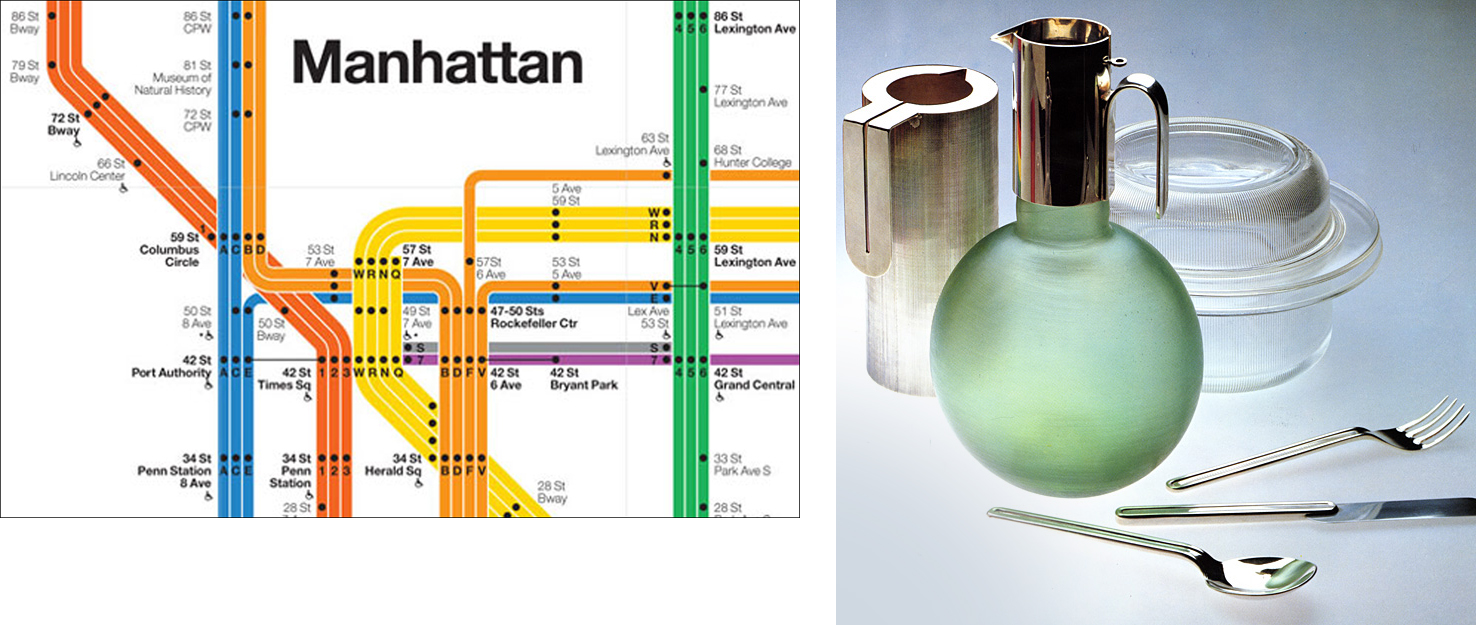

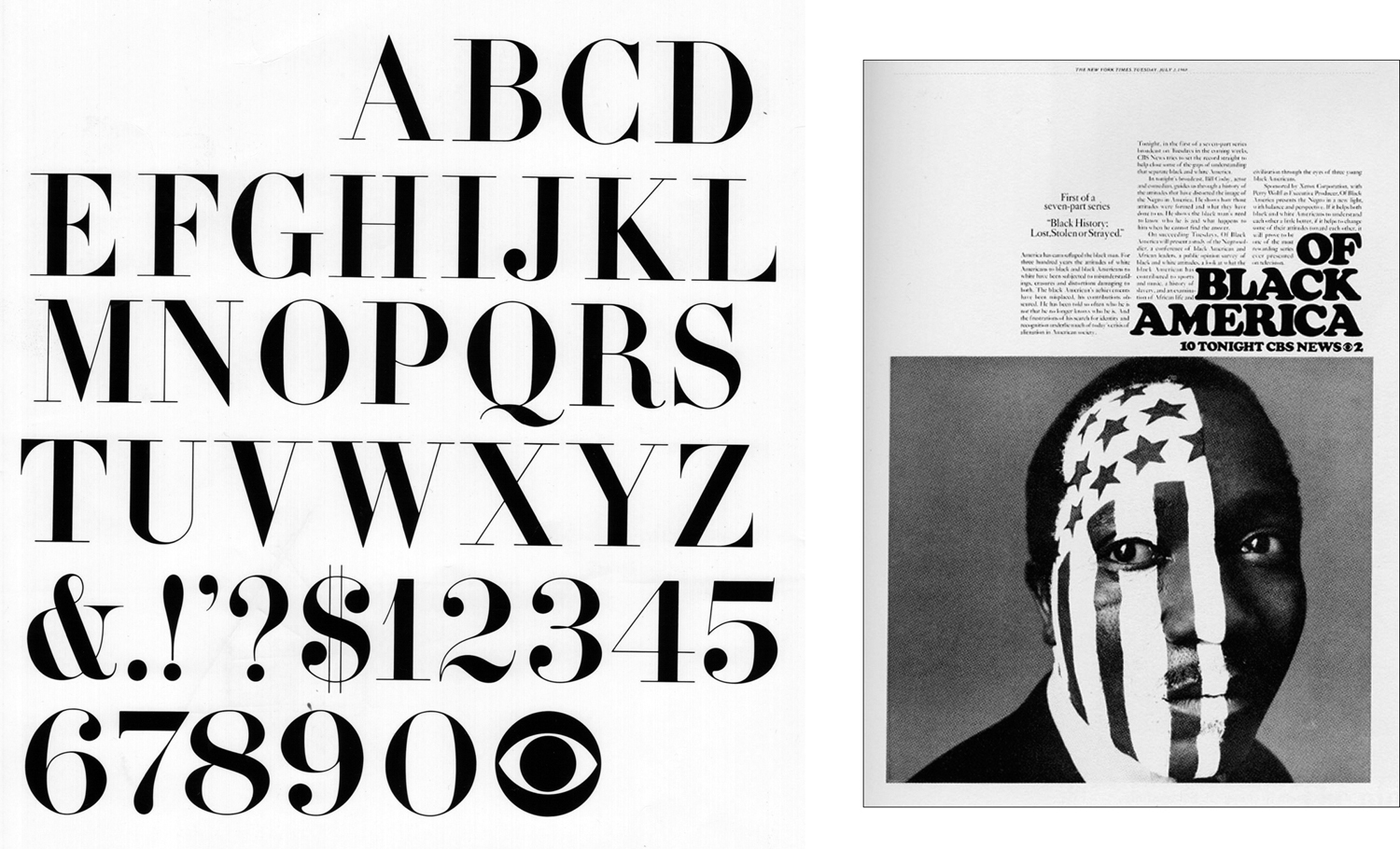

Display type is set photographically, a couple bucks per word in most places, and the spacing is all manual. Photo-Lettering’s work commands a premium, and Bertoli is so particular about type that I usually trace the book titles out in Helvetica on tracing paper to get the exact size and spacing. Then we send the tracing by messenger for them to follow. Bard format uses Helvetica; I use it so much that within a few months I can draw the entire font very precisely without tracing or looking at a specimen.

I show him some of my tracings for Avon titles, and Miedinger nods. “Americans like to set their headlines so very tight! I am used to the spacing of foundry type, where the letters cannot touch.”

He tells me—not quite apologetically—that the foundry had made a mess of Helvetica. “They could not wait for us to refine our drawings. It does not look wrong to anyone until we show them something better. We designers are sellers of details too small to be seen—and that is precisely what gives typography its power. The average viewer does not see it, but they do feel it. The last little refinements are what make it sing.”

I’m a bit shocked. “To most of the world, Helvetica looks like precision made visible. What could you possibly want to improve?”

He says in his clipped accent, “It takes so many tries to get it right. There was too much hurry to get to market when they expanded the offering to include many weights. The appearance of simplicity, you see, is a very complex thing to achieve.”