3. Transitions

From Valise to Expertise

My interviews in Europe and New York help me shift from the desire for a concrete career path to a more flexible, spontaneous mapping process.

Viewing Atlanta from the air, there is very little city to be seen. Its neighborhoods are covered by trees, with a very few buildings poking up every now and again. On the ground, the streets are a fairyland of dogwood and azalea blossoms. It’s enchanting and the people are friendly.

The town has been through a severe crash of real estate prices, I learn, and a number of real estate developers, banks, design firms, and advertising agencies have also suffered or closed. Agencies that have survived are very cautious. It’s against this backdrop of extreme caution and rebirth that I begin my contact process all over again. I carry a newly brushed up Valise Cruiser to design firms and corporate design departments, where I hear different variations of the same story: “We don’t have any staff positions, but could you design this for me by Monday?”

Thus I find my dialogues shifting. I still enjoy learning from creative legends, but increasingly find that entrepreneurs and business leaders also have a lot of wisdom to offer—as buyers of design, as stewards of their brands, and as people who must lead by inspiring.

Don Trousdell: Growing a Style and Outgrowing Style

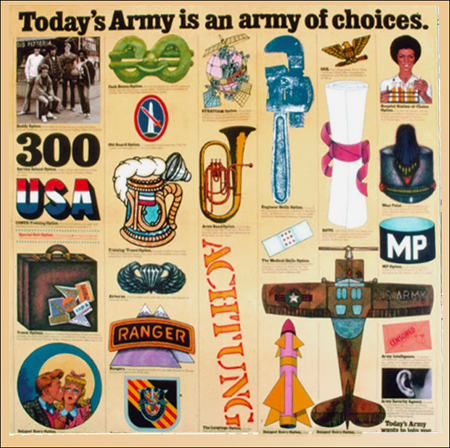

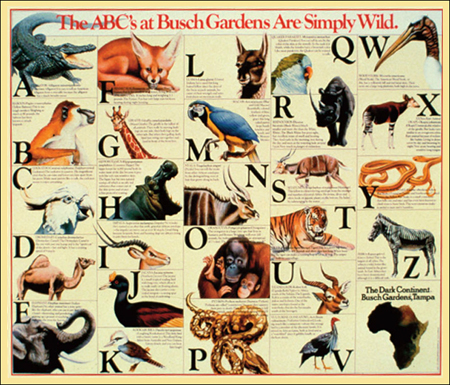

Don Trousdell (1937– ), born in Newark, New Jersey, attended Arts High School, majoring in graphic design. As a student at Pratt Institute he majored in advertising design. Trousdell left New York to work at Pitt Studios in Cleveland. There he started an in-house design studio and worked with many talented illustrators. There he also met his future partner, designer Ron Mabey. The Mabey Trousdell studio started in Atlanta in 1969, working for clients such as Playboy Magazine, the NFL, and the US Army. Over the span of his 40-year career, Trousdell won more than 500 design awards, and along the way helped establish nine different design groups serving clients including Coca-Cola, Turner Broadcasting, CNN Headline News, IBM, Marriott, Kimberly-Clark and World Carpets.

Trousdell taught at Syracuse University and the University of Kansas, and lectured widely; he also judged numerous design competitions. Trousdell retired but never stopped working, producing numerous paintings and mounting more than 35 solo shows. With characteristic dry humor, he remarks of his later work, “The art establishment has been quick to tell me often, ‘You’re not an artist, you’re a graphic designer.’ Known for my themed shows and exhibits, I guess in the end I am still a graphic designer—just with a different client base.”

October 1978

During my student and early professional years, the Mabey Trousdell design partnership was very much in the limelight, winning numerous awards. They were among the few American firms to be featured on the pages of Graphis. When I arrive in Atlanta, visiting them is one of my first priorities.

I find that Ron Mabey and Don Trousdell have parted ways and are working independently. Mabey has his own shop and Trousdell is working for an agency. I call both and start my call tracking, settling in for a long siege. Mabey’s gatekeeper calls back and says they aren’t hiring but I can show my work in September (some months ahead). McDonald and Little’s gatekeeper takes my information and promises to let me know if Trousdell starts seeing portfolios again. I mail a resume to both and go on to other calls. Imagine my surprise when Trousdell’s voice on my answering machine asks me to come in the following week.

“You’re the guy who worked in Pittsburgh.” He is walking fast, looking quickly at the resume I sent and leading me to his office. It has a great view and is crowded with bookshelves and a table on wheels, with orderly piles of projects in progress. After a few more questions we realize we both know Pat Budway, an illustrator with a great talent of his own as well as a fantastic ability to mimic classic illustration styles. I toss out a few other names, trying to think of other acquaintances we might share. Trousdell becomes more animated, eager to hear about his old friends in the Burgh.

“Budway does Leyendecker better than Leyendecker himself!” he exclaims. His demeanor changes again rapidly as he sits down. “I’m on deadline, so this is going to have to be pretty quick.”

The phone rings, and he answers before the first ring is complete. “Jeez, yeah, I thought I had till 4:00—OK, right now.” He returns to me. “Really quick!”

I know the feeling of too little time, so “I can come back later...”

“Nah, it will be the same drill no matter when you come.” I open my sample case and set it before him. I hand him the first piece and sit back. He speeds through most of the work, but looks at it with intensity. He stops at Sexual Secrets, a book I designed that surveys many of the ancient Eastern “pillow books” on sexuality.

“Wow, you did this? How many times in life do you get to do a book like that! Great subject matter! I mean, we hint around about it in advertising all the time, but you just got to air it all out!” Trous-dell jumps up. “Look, stay here and we will talk. I have to punch out this ad, but don’t leave.” His tone changes again, becoming apologetic, almost conflicted.

“Nobody realizes how much time it takes to design. At agencies, they fired all the people who could design and consequently the clients want to tinker with everything. Design it right the first time and don’t let them screw with it.” The old control issue. I guess it will be an issue with every design interview I ever have! He is cutting apart a copy of an illustration, cutting off the head and neck of a turkey. “Here I am cutting apart a Bill Mayer. Mayer is one of the great illustrators, and they don’t give me time to send it back to him to make it fit the layout. What am I supposed to tell Mayer? I tell you, the integrity is gone from the whole craft.”

He is saying this partly to me, partly to the turkey, working rapidly. It appears that the illustration is too tall for the space, so he has to take some sections out of the neck to fit it into the collar of a shirt.

I venture, “I don’t know Mayer’s style—is all his work like that?”

“Oh, Mayer, amazing kid. Your age, and he’s already done more than most of us hope for in a lifetime. He changes his medium and his approach constantly. Not like Budway, who is very controlled, and knows all the great illustration styles, but Mayer—he just has a way of capturing what you mean.”

I remember discussions with Pat Budway, thirty years my senior, talking very candidly about his work. “Budway didn’t really like imitating other people’s styles, he had to do what art directors wanted. He was really a good illustrator on his own,” I venture.

Trousdell looks up at me sharply, remembering I am there and quickening both the pace of both his work and his voice. “Yes, the whole notion of style, it gets in the way of real expression, makes it harder to make your work truly communicate, especially when clients have preconceived ideas.”

He is trimming, looking, trimming, looking again, getting closer and closer to the exact size he needs.

“There are so many styles out there I don’t like and would never use,” I say, trying to segue into a compliment of his work, but this sparks another change in his face.

“The only style I want to get rid of is my own,” he says.

I’m a bit puzzled—here is a guy whose work has dominated the trade pubs, always walking off with top honors in New York and Europe. The Mabey Trousdell style was so recognizable, yet so fluid. Apart from Push Pin, Mabey Trousdell’s style is probably the most decorated—certainly one of the most admired—within the American design scene. And Trousdell says he wants to avoid it!

Don Trousdell’s work varies widely, but is characterized by a love of illustration, and unusually tight integration of the visual concept and writing. His compositions are by turns simple and complex, orderly and chaotic. His work stood out against competing messages; its richness of illustration and painstaking layouts kept readers engaged long enough to appreciate the theme and intent of the client’s message.

Trousdell developed his famous style by trying to have no style; by being true to the needs of each project, his style grows richer and broader. What looks so effortless is really a struggle to keep exploring, to resist repeating past successes.

“You start getting work because people want what won an award for someone else three years ago.” He changes expression for the nth time, and now is talking to his illustration, which has become the embodiment of the customer he is describing. “Get over it, turkey—that was then, we are working on tomorrow, not yesterday!”

Suddenly, I remember the conversation with Heinz Edelmann and I get what he’s trying to say. I’m building a portfolio and trying to make a style, or something that people will recognize and buy. Trousdell has done that and succeeded with it, and at the same time found it constricting. It’s more about finding the right formal aspects for the immediate message than about building a style. I’m struck by this conundrum—trying to build a coherent style is self-defeating, like placing arbitrary limits on the imagination. As soon as your style gets hot, it becomes confining, and you start trying to outgrow it. Trousdell has developed his famous style by trying to have no style; by being true to the needs of each project, his style grows richer and broader. The style that looks effortless is really a continual struggle to explore, to resist repeating past successes.

Trousdell puts a black paper flap on the artwork, puts an agency sticker on the cover, and pulls out a burnisher, leaning hard on the illustration to make sure his paste job does not come loose before it can be photographed. A young account executive in impeccable agency dress strides in as if on cue, and Trousdell hands him the work. The AE flips up the flap, nods, looks at me without curiosity or acknowledgement, and strides out.

“Was it like this at Mabey Trousdell?” I ask.

“Nah, there we took the time—I’d go back to that way if I could, but I have alimony.” Trousdell exhales, sits astride a chair with the back against his chest, and flips through my work a second time. He pauses to admire a David Willardson illustration on one of my Avon covers. “We are blessed with so many great illustrators here, and I wish I could keep them all busy. Me, I can’t draw worth a hoot.” His walls are covered with his skillful concept sketches, so I take this more as an homage to his illustrators than as fact.

“How do you tell your illustrators what you want?”

“I’m like an illustrator’s therapist, sometimes. When I’m not getting what I need from them, I go to visit them, to see what they’re doing. Often the work is too tight, too rigid. I go through their wastepaper bins and pull out the stuff they have thrown out—little sketches, things torn apart in frustration, where the medium got away from them—and I say, ‘Hey, what about this? This is a lot fresher, more exciting. Start over and give me one that’s designed like the tighter version, but is fresh and fast.’ By then there is no time left, so they have to work fast and loose, and it comes out better than any of the previous tries. I think it comes from the pressure.

“Then sometimes the illustrators are my best therapists. If my concept is struggling, they help me figure out what really needs to be said. Things are due so fast, you have to start rendering immediately, which is too soon. Budway used to say, ‘Spend 80 percent of your time designing the illustration, and only 20 percent rendering it.’” Trousdell pauses, remembering some past conversation. “Of course, he was so good, so accomplished, he could pull that off. For me, it’s more like half and half!”

Someone walks by and shoots Trousdell a look, without breaking stride. Another change, and stress knits over his brow.

“Hey look, I want to get together with you and talk more. Can you find your way out?” I speak with Don again on other occasions, and he is helpful in getting me networked in Atlanta. I remark on the similarity of thought about style between Trousdell as designer-art director, and Edelmann as designer-illustrator. Both find that their success at expression creates expectations in the marketplace that add additional challenges to their creative process.

“Style gets in the way of real expression, makes it harder to do work that truly communicates, especially when clients have preconceived ideas. You want to tell them ‘Get over it, turkey—that was then! We are working on tomorrow, not yesterday!”

Dave Condrey and Bill Duncan: Welcome to The Greatest Marketing Organization on Earth

Any new arrival in the Atlanta business community, in any line of work, is quickly drenched in the Coca-Cola corporate mystique. It’s not a conspiracy, nor is it mass hypnosis. There are a few dissenters, of course, but virtually everyone in Atlanta loves Coca-Cola, the organization, if not the beverage. Usually it is both; Coca-Cola is Atlanta’s vin de pays—the vintage of the region. As a little boy, it was my duty to bring a cold Coca-Cola to my dad while he was working on his car. I heard his “Aaah!” of satisfaction after the first swig; I felt I understood the brand. Even so, within a few days of my arrival, I’m surprised by the reverence for the beloved brand. It’s not until the appearance of an unexpected mentor that I begin to drink deeply.

October 1978

I begin calling on Coke soon and often for design business. Newbie that I am, I dial the main number, get the operator, and ask for the person in charge of buying graphic design. On five different days, each operator gives me a different name. By the end of the week I reach each of them at least twice, and figure I must have the whole organization covered. They begin to respond; I get a few chances to show my samples, but not much work. I know from my time in Penn Station Booth 6 that this is just a matter of persistence.

Waiting in the lobby at Coca-Cola USA for an appointment, I strike up a conversation with a big-framed man in a tailored gray suit with an equally outsized sample case.

“You must be new to Coca-Cola,” he observes. He puts out his hand. “Dave Condrey. Let me welcome you to the greatest marketing organization on Earth!” His smile is genuine, yet not without a trace of mischief. I hear his elevator pitch, and give him mine. Condrey comes across as a sort of cowboy-poet turned salesman. The company he represents, Colad, manufactures custom-imprinted ring binders. His commanding size contrasts with his courtly manners and willingness to help.

“Who have you seen so far at Coke? Really. You haven’t spoken yet to Bill Duncan? Let me introduce you. First thing you have to know about Coca-Cola is, no matter how long you have been calling on the company, no matter how many people you know, there is always more opportunity. Bill Duncan is where you need to start. Let me give you some background.”

“Mr. Condrey, Fred says you can come on up.”

Condrey goes to the receptionist and says a few words, and returns to the waiting area.

“Duncan has been here a long time. He may not be at the top of the pay scale, but he has a dotted line to the CEO. Bill handled all of Coke’s internal advertising needs for a long time, but as fast as he and his department are, the volume has grown so much that it is now decentralized. But anything that comes from Mr. Woodruff goes to Duncan. Robert Woodruff, you need to understand, is a merchant prince masquerading as a good old boy. His daddy led the investment team that bought Coke from the Candler family, and Bob Woodruff built this thing”—here Condrey waves his arm casually to encompass the Coke campus—“from a little regional business to a global marketing powerhouse.”

I feel as though my fortunes are taking a turn for the better!

Condrey is getting warmed up, and continues: “You talk to a banker, a lawyer, an accountant in Atlanta. If they’re established in business here, the first thing they’re going to tell you is that they do work for Mr. Woodruff. They won’t say ‘Coke’—every hotdog stand does business with Coke. They will say ‘Mr. Woodruff.’ He is the genius, the leader, the fountain of profits, and The Boss.”

Condrey pauses to think what he might have missed. “At most companies, marketing is just a department. Here, look at this building. The five or six windows on the top floor, that’s where they count the money. Every other window, on every other floor, is marketing. Bottling, that is done at the bottlers. HR, legal, all that is there, but this is an organization built by the smartest marketer alive. David, I’m telling you to keep your ears open every time you step in an office here. You will get an education in marketing second to none.”

I meet many other Cokevangelists, though few are so eloquent.

True to his word, Condrey makes an introduction that rapidly results in an appointment. The Coca-Cola headquarters building is designed and appointed with understated extravagance. There is fine art and big-name designer furniture throughout the lobby and common areas. Yet Bill Duncan’s office is modest, without windows, and filled with projects in progress. It is orderly, but it is obvious that this is the engine room, not the guest hall. There are people coming in and out with constant questions, updates, and needs.

Duncan begins by saying, “So, I must thank Dave Condrey for sending you my way. I don’t often get a chance to see new talent. What have you got?”

I hand him the Valise. I keep my mouth shut except when he asks a question. Every sentence is punctuated with instructions to someone who comes in the open door.

“So, David, on this photographic book, tell me about your role—Shelley, this goes to Grizzard by rush courier—what part did you do on this book?”

I respond, “The publisher had no staff at all, so I took a shoebox full of prints. They gave me a handwritten manuscript in Lakota Sioux, and I trafficked the translation and gave it back to them, ready to print. There were a few bumps, but there always are.”

Duncan looks up from the portfolio as though I have said something profound.

“There sure are! Dana, do we have type back from Swift Tom? Get it to Shelley the moment it walks in. Always bumps!”

The conversation continues. Duncan is jovial and makes detailed observations. “Oh, you use Deepdene! Everyone knows Goudy Old Style—Susan take this to legal, and tell them you will wait there for immediate comment—everyone knows Goudy Old Style; hardly anyone knows Deepdene. You need me, Fred? Come on in. Deepdene, it’s the best thing Goudy ever did!”

Duncan closes the Valise. His desk is a haystack. I have my card out to hand to him, but it is too far to reach. He navigates around to take the chair beside me, and then thinks better of sitting.

“David, your work is very professional and Lord knows we need all the good talent we can get. Let me give you a few insights on howde-do at Coca-Cola.” He walks to the door.

“You are still holding your business card in your hand, and the interview is almost over. I am telling you that by the time you got to here”—he is one step inside his door—“you should already have smiled, handed me your business card, and said your name clearly and cheerfully.” He pauses. “Come over here and do that for me.” I comply, and he says, “Why do I ask you to do that?”

“Good Southern manners?” I venture.

Duncan laughs. “Good answer! But understand: Every executive and manager here gets a hundred vendors a week flooding through. No way to remember all those names. I want your business card in front of me where I can call you by name three times during the meeting, so I remember who the hell you are. Simple as that. If I have any use for you, I’ll want to make a note on your card about something I saw.”

It is great to work with someone who wants to see you succeed in their organization!

Duncan motors on. “Now, you got an appointment here. That gives you the right to ask me for my card. Don’t you ever leave any office at Coke without getting the occupant’s card. There are hundreds of us, and we don’t like having our names misspelled or our titles wrong. Titles matter here. If you don’t ask for my card, you must think I’m unimportant. Write my name in stone above your desk and get it right. Pronounce it right. Remember who reports to whom. You don’t want to ask me”—here he gestures to mean any of my potential clients at Coke—“who I report to. But it’s fine, once you are working for me, to ask me who else reports to whom. Get it?”

Duncan strides back around his desk for the next lesson.

“Your friend Dave Condrey, he is a master at this organizational stuff. You know how many competitors he has here? Selling pretty much the same products he sells? Must be two dozen. You know how many of them I give business to?” Duncan pauses for emphasis, but not long enough for me to hazard a guess. “All of them, David, all. You know why? Susan, have we got proof back from Swift Tom? They’re sweating bullets upstairs. We have enough programs needing that product here to swamp any factory, including Condrey’s. But you know who gets the best projects? You got it. Why? Condrey any faster? Nope. Lord knows he isn’t cheaper! It’s because he knows the people here, the structure, the unwritten rules. James, you need me? Sure, let me see it. Case-Hoyt printing it? OK, get going. Dave knows about relationships here that I wouldn’t have guessed, and I’ve been here for centuries! You got the courier here waiting for this? Go, Jamie, go! When your ‘bumps in the road’ come along, I want my work in the hands of someone who will know.”

Duncan is holding my card and he looks at me emphatically.

“David, understand I am not always around to give my vendors the answers they need. Even if there were five of me here 24/7 my vendors would still not get all the answers they need. So I want my work with Condrey, who knows not to call my boss to ask something basic. Hey, Will, tell the boss he will have his storyboard a day early. The work goes to the people we can trust to get it right. Your ‘bumps in the road’ aren’t just expensive in money. They entail risk for me. Mistakes made in haste can take a very long time to repair. I can get a hundred projects right, but I get one crucial one a little bit wrong or a little bit late, and things get ugly.” He shakes his head ruefully to finish the sentence.

Duncan’s pace escalates; he exhales and smiles. “You get the idea. Condrey watches my back. He will get the information from an assistant or, Lord knows how he gets it, but he never”—knocking on the only square inch of wood visible on his desktop—“lets us down. You learn what he knows and you will be invaluable to us, just like he is. I’m telling you to ask him to coach you.”

“You can have the best design in the world, but if you don’t storm in and sell it to me with enthusiasm and finesse, well, I won’t trust you with our best work.”

“Now I’m not telling you all this because I think you are an amateur designer. On the contrary, I think you’re a hell of a designer and you have a fresh perspective that we need. I do think you are a bit of an amateur salesman, and that is a sin people here won’t tolerate. We work for the greatest salesman that ever lived. You can have the best design in the world, but if you don’t storm in and sell it to me with enthusiasm and finesse”—here I flash on Condrey, welcoming me to the greatest marketing organization on Earth—“I won’t trust you with our best work.” A bell goes off in my head. For what seems like a hundred interviews, designers have been telling me how client trust is the key to doing great work, and agonizing over how hard it is to gain that trust. Here is a guy who buys hundreds of creative assignments a year, and he is telling me how to get his trust! Quality+Enthusiasm+Finesse=Trust. Could it really be this simple?

“I want you to do a project. We gave this project to someone new who used up all our time and didn’t understand the project. I want you to take this sketch”—without a bit of rummaging, he pulls a manila folder out of the haystack—“and read this creative work plan. Then get me something that proves to me that you really did all the great work in this portfolio. If you have questions, call Condrey and get him to explain. Call me and give me a price—someone will call you with a purchase order. You can’t bill me without the PO. I needed these designs yesterday.” He’s down the hall and gone.

I decide to park in the lobby and make notes. Dave Condrey appears from the elevator bay, a supersize man trailing an even more supersize sample case on wheels. I flash on a Jim Burke image—a switching engine pulling a loaded freight car.

The engineer wheels up and smiles, “So, how did your meeting go with Mile-a-Minute Duncan?”

“He gave me a project. And he sure thinks highly of Dave Condrey!”

Condrey feigns exasperation. “He had better! All the times I have dumped our factory upside down to meet his impossible deadlines!” Still smiling, “Duncan is a prince of a fellow. I have a crisis to quell now, but I want to hear about your project.”

Condrey meets me for coffee the next morning and gives me some of the unwritten rules. “Start with the obvious. To most of the world, Coke and Pepsi are like, you know, Laurel and Hardy; rivals who can’t live without one another. Their employees meet on a golf course, they are cordial. But inside the Coke organization, you never mention beverages that begin with P! You also never forget they are the elephant in the room. To them, it’s thermonuclear war. You never mention that organization by name. You always say ‘The Competition.’”

He moves on. “You’re a designer, so you know the Coke colors?”

“Pantone Warm Red and white.”

“What’s the one color that does not exist within Coca-Cola HQ?”

“Pantone Pepsi blue?”

“Pantone anything that even smells a little bit like anything close to blue! My factory makes swatch books of all the colors of binding materials we offer. But before I hand one out at Coke, I remove all the blue swatches.” He winks. “A word to the wise.”

Aha: An inherent contradiction: buyers are always looking for a fresh perspective, yet they want someone who knows their company like an insider. As creative providers, we must quickly develop an insider’s instincts—yet keep the wide-eyed wonder of a newcomer.

Condrey could dismiss his customer’s mania about “The Competition” as an amusing customer foible. Instead, he makes it an article of faith—even to the point of modifying swatchbooks so that the odious color blue does not exist! Condrey has grasped an essential truth: Competition is an important driver of brand excellence. He reels off other job-related details; my breakfast is cold but I have an outline for a Coca-Cola encyclopedia.

“Now, what’s your first objective?” he asks me.

I’m about to say something about the design process, but Condrey answers his own question, “Purchase order! You can’t get paid without a purchase order, and if you submit an invoice without one, you make Bill look bad. Duncan likes your work, and he is short of fresh talent just now. Show him you can deal with their paperwork, and you will get more work from him than you know what to do with.” Condrey continues, “By the way, Coke people are in such a hurry, they can give you the impression that the cost of things doesn’t matter, but it does, greatly. It’s OK to talk money early, often, and whenever they change the mandate you have outlined on your proposal. Which,” he winks, “has been known to happen! All this is doubly true when starting a relationship. Every person at Coke is a new relationship. The pricing expectations for Duncan may differ from those for the guy in the office next to him. Even if the project is so open-ended that you can’t price the whole thing, give them a price to get to the next step. Got it?”

“Talk money early, often, and whenever your client changes the mandate you have outlined on your proposal—which has been known to happen!”

I’m about to ask something else, but the waitress is clearing the table and Condrey the switching engine is revving up to move cargo. “What’s your next objective? Deliver fast! I have no idea how long it takes you to come up with an idea, but if I were you I’d try to get him something less than twenty-four hours after you phone in your PO.”

Condrey’s coaching proves to be the start of a variety of projects. There is an inherent contradiction to all this: Duncan—and many buyers of design like him—are always looking for a fresh perspective, yet they want someone who knows their way around the company like an insider. As creative providers, we must quickly develop an insider’s instincts to avoid blunders, yet keep the freshness and wide-eyed wonder of a total newcomer.

Robert Woodruff: Take Out Everything but The Enjoyment

Robert Woodruff (1889–1985) is known for the leadership that built Coca–Cola from a struggling regional enterprise to a global marketing powerhouse. Born in Columbus, Geogia, he moved to Atlanta. He was an indifferent scholar, but his exceptional skill as a salesman at White Motor Company quickly resulted in promotions and leadership roles. His father, Ernest, as president of Trust Company Bank, led the syndicate that took Coca-Cola public, and the fledgling company needed a dynamic leader. Both Woodruffs had invested in the stock offering, and it was underwater. At age 33, Robert Woodruff became CEO and began one of the most amazing growth stories in American business. He not only grew the business, he established a culture of competition, civic involvement, and marketing prowess that attracted top-flight talent. A philanthropist of almost unimaginable generosity, Woodruff and his wife, Nell, gave away hundreds of millions of dollars over their lifetime, benefiting Atlanta and many people worldwide. Woodruff was involved in shaping Coca-Cola’s brand image and often personally reviewed advertising campaigns for content and design.

1982

For my first few years in Atlanta, I make the rounds to the major ad agencies, design studios, and printing companies with the Valise. My portfolio consists mainly of book designs. There are few book publishers in Atlanta, but because so many companies have cut their staff, it’s a pretty good time to be an available freelance designer. My contacts result in a stream of freelance work that grows steadily.

The amazing thing about making direct calls is how long people remember you. I get a call from Case-Hoyt, a printing company I called on two years ago. Their art director remembered I had done books, and they have a book to design, about none other than the Coca-Cola magnate Robert Woodruff. Actually, it is a biography of his wife, Nell. The Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing wants to publish a biography about “Miss Nellie,” as she is affectionately known, and give it as a present to all the students at the school. Equally important, I learn, the book is to be a present to Robert Woodruff, who is 92.

Even though Dave Condrey has briefed me on the Coke organization, I have only a northerner’s understanding of Woodruff’s importance. Only later, after the book circulates with my name on it, do I understand the mythic quality of the man: a tough yet charismatic boss, an aggressive and opportunistic businessman, and a philanthropist of great generosity. There is a mythology surrounding his extravagant lifestyle, his hobnobbing with presidents, his devotion to his wife, and his vocal claim that he never read books. I decide not to remark to my client on the irony of creating a book for a man who claims not to read.

The art director gives me the name of his chosen biographer, Doris Lockerman Kennedy. “You’ll like her. She’s written half a dozen books. She is a contemporary of Mr. Woodruff, but don’t let her age fool you, she is sharp as a tack. She has outlived several husbands, including the man who shot John Dillinger.”

Ms. Kennedy is indeed delightful, and it turns out her manuscript is done as professionally as any by an OUP author—and more quickly. Ms. Kennedy has an amazing memory for historical subjects, and many of her insights find their way into the design of the book. She takes me on a guided tour of the School of Nursing.

“Nell was trained as a nurse before she married Bob and became the spouse of the richest man in Atlanta. It was her passion for nursing that lead the Woodruffs to donate so generously to the Emory School of Nursing. Here is her portrait, one of several Mr. Woodruff commissioned. It’s an Elizabeth Shoumatoff—you know the name? Of course not, you are too young. She was the high-society portraitist. After Nell died of an aneurysm, Mr. Woodruff purchased this wall-mounted vase and paid for a fresh pink rosebud to be placed in the vase next to her portrait—every day.”

This is the type of insight designers seek as a way to personalize design. So this story becomes a foundation for the book design, and a rosebud ornament to be used on the chapter titles and binding of the book. It turns out to be an important detail.

Some days later, I get a call. Case-Hoyt likes my design, and I am to show it to Joe Jones before it is presented to Emory. I’ve heard of the Jones brothers, Joe and Boisfeuillet, who have their names on buildings at Emory University.

Kennedy explains that Joe Jones is Mr. Woodruff’s man at Coca-Cola, now that Mr. W is retired.

Despite my coaching by Condrey and project experience with Duncan, I feel I am being admitted to the inner sanctum. I am shown into a calm, richly appointed office, greeted cordially and offered refreshment. Since I was hired by Case-Hoyt and Emory is the client, Mr. Jones does not know me; so I take time to do a little verbal resume, being careful to include Oxford and my work for Duncan along with recent projects. We review visuals for the design. I explain the choice of font and paper, but see that he is not interested in the technical details.

“The binding is navy and white, to match the uniforms worn by the undergraduate nurses.” Jones perks up. I realize I just have to talk about the emotional connections. I replay Doris Kennedy’s story about the rosebuds, then point them out on the binding design and pages.

Jones nods more vigorously. “Robert will like that. He is not really that much of a reader, but he will like the subject, the photographs, and the rosebuds. It’s too bad there’s no color in the book.”

“The Elizabeth Shoumatoff portrait of Nell that hangs in the lobby of the Nursing School is in color. We could use it as the book’s frontispiece,” I suggest. Jones nods.

“You have done well. Please proceed. Will we be able to have this before Mr. Woodruff’s birthday?”

Design approval, proofreading, and printing move ahead on schedule. I go on to other things.

“David, Joe Jones here. I have the first copies of Devotedly, Miss Nellie back from the bindery. Do you want to see them?”

Again I am in Jones’s office. “This looks great,” says Mr. Jones. “I want you to accompany me when I show the book to Mr. Woodruff. Ms. Kennedy and Dean Grexton want to be there, but they’re both tied up, and this should not wait.”

The Woodruff mansion holds a commanding position in Atlanta’s Buckhead neighborhood. The sight of it brings a bit of apprehension. Woodruff personally oversaw many of the ad campaigns that put Coca-Cola at the forefront of American business. What if he has strong opinions about typography? What if he rejects it?

Jones says, “This should be a cakewalk. Let me do the talking unless there are questions about the design.”

Woodruff is seated, a newspaper and a humidor on his desk. When we enter, Jones and Woodruff embrace cordially, like wartime heros at a peacetime reunion.

“We have brought you something special—a memory of Nell,” Jones tells him.

Woodruff’s eyes light up momentarily. Jones is holding the book in his hands. Woodruff has not reacted yet, but is paying attention. I have heard he attends board meetings even now. Is it true that he never reads books?

“And, look at this,” Jones continues. He opens the book to the color portrait of Mrs. Woodruff, and the title page with the decorative border of rosebuds. “It has your rosebuds! On all the pages!”

Woodruff takes the book in his hands, looking intently, finds the pages of photographs, and turns a few pages with a wistful air. He returns to the frontispiece, and browses a bit more.

Jones nods at me approvingly. This is why I love designing books. Books can contain a story, a person, an epic, a tragedy. They can transport us to our best places.

Woodruff speaks up; his voice is thin, but the air of command is unmistakable. “Be sure to tell Edna that Nell and I—how much this means to us.”

Jones, who is possibly the most diplomatic person I have ever witnessed, intones, “Of course, Bob, of course. Edna was to be here today but had to leave on urgent family business, and asked that we not delay giving you the book. And I want you to meet Mr. Laufer, who designed the book.”

I come forward, Jones’s hand on my shoulder. Woodruff shakes my hand, and for an instant, I am in the gaze of this man—full of years, commander of millions, and stuff of legends. In that instant, a voice inside whispers, This is your only chance, learn something important! Dave Condrey’s greeting comes to mind—“Welcome to the greatest marketing organization on Earth” and I wonder if he can tell me how he made it that way. Instead the sentence unfolds, “Mr. Woodruff, sir, Bill Duncan says you’re the greatest art director that ever lived. What’s your secret?”

Bill actually called Woodruff a salesman and marketer, but I don’t think he would have minded the attribution. Woodruff’s gaze deepens, and his posture relaxes ever so slightly. His words are a bit halting, but the man is still all there.

“Bill worked for me for so long, after a while he knew what I was going to say, before I did!” His eyes drift out the window, as though to see if the headquarters building is in view, and he recalls, “Bill, all of our top people, almost always had good ideas—great ideas—sometimes so many ideas it was hard to choose. But, you know, the message is really simple. Heck, Coca-Cola—it’s just something you enjoy drinking! But it’s so easy to get too many good ideas competing for attention. All I did was remind Bill how simple the message is. You know, half our ads just said, ‘Enjoy Coca-Cola.’ I just reminded him to take out everything but the enjoyment.” His eyes come back to me. “Just like your book—nothing gets in the way of Nell’s...” He is back in the book, for a moment. Woodruff looks me in the eye for the first time, as if to complete his sentence. “Yes, it’s her.”

I think that of all the client compliments I have received, this one is perhaps the most soul satisfying. To design a biography devoted to an extraordinary woman, and then have the book recall that woman to the love of her life, that is about as good as one can hope to be. Jones is a little surprised—he probably didn’t expect me to speak up. He does seem pleased that I have brought Woodruff some pleasant memories with the book and with my question.

“For Woodruff, talking was for entertaining and making friends. Mentorship is leading by example, and leadership is about doing.”

As we return to headquarters, Jones asks, “So, what did you think of Mr. Cigar? That’s what his executives used to call him.”

“Even at ninety-two, he’s a commanding personality. There were many things I would like to have asked him, you know, about how he inspired so much loyalty.”

Jones smiles. “Oh, you wouldn’t get much out of him; he mentored his people by example, and by making assignments and monitoring the results—not by talking. Talking, for Mr. Cigar, was for entertaining and making friends. Leadership was about doing. He would never let a compliment stick to him—he always conferred it on his team. I can’t count how many times I heard him say, ‘There is no limit to what can be accomplished if it doesn’t matter who gets the credit.’ By the way, he’s not one to give out compliments often. You found a way with your rosebuds to make the design very personal.”

From that day to this, whenever I prepare for a meeting with a client, I envision Bill Duncan spreading out a series of designs, and Mr. Cigar saying, “Take out everything but the enjoyment!” Woodruff is right: there is usually no shortage of good ideas. Great leaders know their mandate and lead by keeping the troops focused on the most fundamental message. The encounter gives me the courage to pare away inessential ideas, no matter how good they may be.

Advice from the greatest marketer on Earth: “Take out everything but the enjoyment.”

Lawrence Gellerstedt, Jr.: Leadership is Developing People

Lawrence Gellerstedt, Jr. (1924–2003) graduated from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1945 with a degree in chemical engineering. He served in the US Navy, and joined Beers Construction in 1946. He would stay there his whole life, becoming president in 1960 and owner in 1969. Gellerstedt and his son Lawrence III built strong management teams and presided over the construction of many landmarks in the southeastern US, including buildings by world-famous architects Philip Johnson, Richard Meier, and John Portman. A prodigious fundraiser, Gellerstedt led many successful capital campaigns for schools, hospitals, arts organizations, and charities; his work enriched many communities. He received numerous service awards, and endowed a professorship in bioengineering at Georgia Tech. During his tenure as president, Beers annual sales grew nearly a hundredfold to $1.2 billion.

April 1983

The Beers headquarters is a house in central Atlanta, surrounded by much larger commercial office towers. I enter and am shown to Lawrence Gellerstedt’s office. It is decidedly modest. Beers builds very sleek, international-style buildings, so this very nonarchitectural office is homey by comparison.

“They got you some coffee, I see. Good,” says Gellerstedt by way of a greeting. “Look, I’m expecting several calls on projects with crises, so we’ll just have to work our conversation around that.”

Gellerstedt is lean and decisive in his motions, as if everything is a move on a chessboard. He runs down the things he feels he wants to emphasize about his company: trustworthiness, strong leadership, good values, excellent craftsmanship, financial stability. This is what I expect, but I’m not learning the thing I most need to know: What makes this guy such a phenomenal success? How does he accomplish so much? How does he command the respect of so many Atlantans, both blue-collar and blue-blood? His phone rings in the middle of a sentence. He gets up from his desk to answer his phone, which he keeps on a credenza halfway between his desk and the door. There is no chair near the phone; he stands to talk.

He listens for a moment. “How did that pour go?” He is staring out the window, visualizing the progress of a partially finished structure. OK, you tell me how many extra men you need and you’ll have them.”

I need to figure out the real value proposition at Beers. Sometimes it is the hardest thing to isolate; even the customer does not always see it. “I have no problem telling the Beers story as you describe it. But what I’m hoping to get today is what sets Beers apart. Why is it growing, how do you finish such large projects on time and on budget? Why are Beers customers and employees so loyal?”

He takes another call to play hardball with a subcontractor who is holding up a project. He returns to my question as if there had been no gap. “You see that mud on my carpet? My cleaning staff knows they are not to vacuum that up. I need to know everything that happens, so I want my job captains to be able to walk in here without worrying whether they are messing up anything. Makes ’em feel they can tell me just about anything, no matter how bad.

“You see that Pontiac out there? Most of my competitors have Mercedes sedans. Some of ’em have their own aircraft. Our business is very cutthroat on price. Buildings are so expensive; I get a lot of price pressure. I drive up in that car and tell them this is the price to do the job right, they believe it. If I stand up in front of a civic group and tell them we urgently need to raise twenty million dollars for a clinic, and here’s my check to get the ball rolling, I want them to say to themselves, ‘He must really believe in this if he is willing to give money rather than buy himself a new car.’”

The pieces are beginning to fit together. I decide to ask about some of the other unexpected things I see.

“You see that mud on my carpet? My cleaning staff knows they are not to vacuum that up. I need to know everything that happens, so I want my job captains to be able to walk in here without worrying whether they are messing up anything.”

“I notice you don’t keep your phone within reach of your desk.”

“I get more done standing for a lot of short conversations than sitting for fewer longer ones.”

“I get more done standing for a lot of short conversations than sitting for fewer longer ones.” I am reminded of Edelmann saying “You get comfortable, you get lazy.” This man could not be more different from Heinz Edelmann, yet they are both ferociously productive, so on that point, they agree. I must look at discomfort as opportunity!

“Mr. Gellerstedt, my job is to make this campaign—all your graphics—say the right thing, but also look and feel and sound right. What insights can you give me about what you want to get across?”

“Look at my office. I don’t know anything about design or style or how to make things look good. Heck, that’s why we hired you! We get these drawings from architects and I can’t tell why they have designed their buildings certain ways, but I just follow their drawings and bam, the buildings look great.

“People will only hire you to do a big project when they trust you. It helps if they like you, but they absolutely have to have trust. Trust comes when what others say about you is better than what you say about yourself. When you make claims beyond your reputation, you are taking a big risk.”

Here is a client who probably knows more about projecting a personal image of trustworthiness than ten branding experts, turning over exactly the control I need to do good work for his company; telling me, in effect, “That’s your turf!” I realize this is his style of leadership, to pick good people and push the responsibility on them. It’s a great motivator, to know you are empowered to act.

Gellerstedt goes on: “What else. I don’t know that we really are all that much different. We treat our workers right. We want to keep the good ones for life. Let me give you an example. I had been calling on a big developer, John Wright, for four or five years, trying to get his business. They were happy with their relationship with Squire, and I couldn’t budge him. The fact that he was loyal to Squire made me want him as a client all the more.

“I don’t know anything about design or style or how to make things look good. Heck, that’s why we hired you!”

“So here we had an endorsement from a key man in a competitor’s organization bring us a relationship I couldn’t win with five years of sales pitches. The way you treat people does a lot of your selling for you.”

“Then one day I get a call from him asking if we have the capacity to take on an office building for him. Usually someone starts you out with a small project, but this isn’t a starter-type project. I said, ‘What made you decide to call us now?’ Wright says, ‘Jimmy Saronsen called to tell me he was leaving my project. Jimmy says he has always wanted to work for Beers, and finally got the chance. So I figured, if I have to hire Beers to get Jimmy, then Beers must be as good as you have been telling me all this time!’ So here we had an endorsement from a key man in a competitor’s organization bring us a relationship I couldn’t win, even with five years of sales pitches! If I can treat my employees and subs as well as I treat my best customers, then the word on the street does a lot of selling for us. So, to answer your question, I just you want to make us look on the outside the way we really are. An all-around good place to work with.”

Gellerstedt makes it sound so simple, but clearly if it were simple everyone would be doing it. I am still at a loss for how to translate these values into visual form.

“David, I may have time for one more short question.”

I have to get to the center of things, fast.

“When people talk about you and Larry and what Beers means to the community, they always seem to use the word ‘leadership.’ How do you define leadership? What makes your way of leading more effective than Squire’s, for instance?”

“Now, I didn’t say we were better than Squire, they’re a damn good firm ...” For the first time in our interview, Gellerstedt pauses. Then he picks up momentum:

“Leadership is developing people. Every day, I have to push responsibility at people, ask them to do something that they feel is over their heads. Some succeed, some require help, some drop the ball. I have to force the project managers who report to me to do the same with their staff. Somebody doesn’t show up for work, they have to plug in their next best person. I will tell them, ‘I don’t want you doing that job yourself. You reach down and pull up someone and give them the chance. I want to know who you pick.’ I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had that conversation, and that manager will say, ‘I don’t have anyone.’ But as a boss, I can’t let them push their leadership responsibility back on me. I’ll say, ‘You just give me a name!’ That forces them to look at the people reporting to them with new eyes. See some potential that isn’t being used. I’ve learned that a lot of times the person we promote does a much better job than the person who didn’t show up.”

“Leadership is developing people. Every day, I have to push responsibility at people, ask them to do something that they feel is over their heads.”

“All right, David, sure have enjoyed talking to you. Now you get out of here and make us look good without promising something we can’t deliver!”

“I think you’ve convinced me there is nothing you can’t deliver,” I tell him.

“Good lad, now go convince the rest of the world.”

Caroline Warner Hightower: Design as Magic

Caroline Warner Hightower (1935— )was born in Chicago. Her father, Lloyd Warner, was a prominent anthropologist. She began her career as the advertising manager and graphic designer for the University of California Press. In 1968, she became grant officer at the Carnegie Corporation. There she gained experience in fundraising that she then applied as a consultant to many cultural and philanthropic organizations.

Hightower was hired as the executive director of AIGA in 1977. For the better part of two decades she worked tirelessly to create a vital and dynamic organization that could effectively represent the needs of the design community. During her tenure the membership increased from 1,200 to 11,300 and chapters were established in 38 cities. Programming grew and flourished. In addition to initiating AIGA’s highly influential national biennial design conferences, the national business conference, the AIGA library, and the AIGA Education Committee, Hightower was the architect of some significant stand-alone programs and publications. These include a national symposium titled “Why Is Graphic Design 93% White?” and the publications United States Department of Transportation Symbol Signs, Graphic Design for NonProfit Organizations, and AIGA Standard Contracts for Graphic Designers. Since leaving AIGA, Hightower has continued to work as a program-development and fundraising consultant. Among the institutions she has worked with are the American Numismatic Society, American Society of Media Photographers, New York University Arts Administration Program, United Way, and the Clio Awards. She was honored as an AIGA Medalist in 2004.

1987

Nine years have passed since my my interviews with the New York designers. Ed Gottschall’s replacement as executive director of AIGA does not work out. The organization is in disarray—membership is down, finances are uncertain. AIGA’s board reaches out to a new executive director, Caroline Warner Hightower. Hightower wades in and gets AIGA back on its feet and growing. As a member at large in Atlanta, I am a bit removed from all this, until ...

Hightower makes a visit to Atlanta and a dozen other cities. She has announced a bold initiative to start a chapter system and grow the membership. I am one of ten members at large in Georgia, so she calls, and we have lunch.

Hightower begins with some observations about the changes in the profession, the declining role of New York as the capital of the profession, and the need to involve everyone.

I begin a bit skeptically: “Why chapters, why now? All of us look at what we get from AIGA for our membership fee, and many years it amounts to a listing in the membership roster and some invitations to spend more money entering shows.”

Hightower has startlingly good answers. “Let me tell you how this started. I got a letter from a member at large in Cleveland, Ohio, telling me that they had decided to form an AIGA chapter. On their own they just did it. They needed resources, a community network.

“Designers need a safe zone, a place where they can teach and learn from one another. Awards are nice, but we—any professional association worth its salt—are all about building a lifelong network. It’s both survival and growth.”

Having grown up in Cleveland, I can picture this perfectly. “Same town that started rock and roll, or at least we Clevelanders lay claim to having invented the term!”

Hightower says, “I hadn’t thought of that, but I like the spirit of it. You were enumerating the benefits of AIGA membership, but you forgot the most important one—the network.” I tell her the story of my first visit to Ed Gottschall, lost portfolio and all. “Exactly!” she says. “Now today I can’t see every young designer that comes through, but the idea is the same. Designers need a network, a safe zone, a place where they can teach and learn from one another. Awards are nice, but we—any professional association worth its salt—are all about the network. It’s both survival and growth. Designers change jobs, they have to! The business world is changing. Corporations add and cut design departments rather quickly relative to other job categories.

“Design matters more than it ever has before. We need to move beyond giving awards to each other that only designers understand, and start being about demonstrating why design matters to the world. And we need to help these wonderful creative people cope with the changes they face. AIGA has always been about the network, but the network needs to get bigger, fast. Design, for us, is a process. It can even be a fairly laborious process, when we get clients changing things by the hour. But for most of the world, who don’t ever see the process, design is magic with a capital M. We have to be about sharing that magic.”

“Design, for us, is a process. It can even be a fairly laborious process. But for most of the world, who don’t ever see the process, design is magic. We have to be about sharing the magic.”

This makes me think of George Nelson, talking about the benefits of design without saying anything to his prospects about process. “Magic” is the wrong word to use with my clients, but she is right.

Hightower goes on. “Design simplifies, transforms, makes things look better and work better—and many people will pay a premium for it. AIGA needs to be about promoting the electricity that design brings to business, to our broader culture. Not everyone has the ability to visualize, or grasp problems in the way designers do. But except for the visually impaired, everyone sees how a great design enhances its subject.”

“I love designers. I love how they reframe questions to make them more exciting. We give the same briefing to 100 designers, and get 100 posters that all deliver the message, yet are wildly diverse.”

I remember Victor Papanek designing for underserved populations and say, “Design can include the visually impared too.”

Hightower gets a boost from this observation and kicks it up a notch: “I took the job at AIGA, even with the organization in somewhat of a mess, because I love designers. I love how they think so differently from other business people. I love how they reframe questions to make them more exciting. I love how they convert abstract problems into concrete images, yet it is somehow filtered through their own personality. You can give the same poster assignment to a hundred different designers, and get a hundred good posters that are wildly diverse.” I find myself thinking that her conviction and confidence would make Bill Duncan proud.

I remember that Hightower worked for a short time as a designer but spent more time in other areas. I don’t want to be rude, but I am concerned about whether someone who is not a designer can pull this off. I try to say this obliquely. “I’m curious, what makes you so convinced this is what designers need? Does the board agree?”

Hightower must have heard this question in many ways from other people. She confides that her being a design aficionado—but not a designer—caused some uneasiness among board members when she was interviewing for the job.

“When I applied for the job,” she says, “the board asked how many years I had been in the profession. I told them I had only practiced graphic design for a few years, but that I been a singer in a bar for a few months. I’m not exactly sure why, but that put the designers in the room at ease. Singing in a bar seems to everyone much more difficult, fairly creative—and anyway, what difference does it make? as long as we like each other!”

“Here is the important thing: Designers are great at seeing the needs of others and making them visible, comprehensible, fun. Designers are much less good at seeing themselves. They get excited about details too small to be of any value. AIGA helps them be practical.” She is “selling” her specific organization, but the comment applies more broadly as well. I muse on her comment about small details. I think of how Dorfsman would disagree—how he stressed that getting the subliminal details right makes the visual pop. I think of James Craig’s discipline, keeping the powder dry until the right job comes along where you can chase perfection. Then, as always, I think of Fred Schneider’s poster: “To be right is the most terrific personal state that nobody is interested in.” I don’t go into it with Hightower, but clearly, there is no universal answer, there is only the most comfortable resolution for each individual designer.

Hightower announces that AIGA will hold its first national convention in January of 1985, in Boston, and that she is asking all cities to have chapter officers elected by then and have at least three delegates there. I am ready to step up, but my inner skeptic resurfaces. “How do you know anyone will see the value in attending a national convention?”

She lets slip the mysterious smile of a singer who knows how to work the audience. “Paul Rand and Milton Glaser will be there.” I book my tickets, and our Atlanta chapter gets off the ground.

Saul Bass Encore: When the Student is Ready, The Teacher will Appear

1987

For some years after hearing Saul Bass’s lecture, I keep looking for the film he described, Notes on Change, to appear in theaters or as part of a film festival, but it never does. Maybe the title changed? Then in 1989, at the second AIGA national convention in San Francisco, I see Bass again. We happen to be part of a group walking from one venue to another, and I am able to introduce myself.

“Mr. Bass, I was among the audience you addressed in Pittsburgh in 1970. I remember vividly how you read to us a script for Notes on Change, and I thought it was a world-beater. I have been hoping to see it and was just wondering if it ever got made?” Bass looks a bit startled, and says no, it is one of many pet projects from that period he had not been able to get funded.

“Now I have the money that I could make it myself, but I keep getting calls from the studios to do this title or that project, and I never tire of that thrill. I have come to be at peace with being a designer. I need the intensity of the relationship with a great team and a demanding director or client to bring out the best in myself. The personal projects—I don’t know, someday maybe.”

“I have come to be at peace with being a designer. I need the intensity of the relationship with a great team and a demanding director or client to bring out the best in myself.”

I thank him and tell him that I still hope he will find time to make Notes on Change. The old smile flashes: “If you remembered it this long, you have already seen it!”

In this short exchange, Bass resolves for me the crux of the design versus art definition that has eluded me for so long. The product—design or art—is not the locus of the distinction. Nor is the type of aesthetic experience—gallery contemplation vs. utilitarian satisfaction. Finally, the distinction has nothing to do with the remuneration, or lack thereof. What distinguishes design from art is the person doing the work. An artist is internally motivated, bringing work out of an inner reservoir.

Aha: What distinguishes design from art is the person doing the work. An artist is internally centered, bringing work out of an inner reservoir. The designer is other centered; finding a dynamic relationship with a client brings the work to its fullest potential. One can wear both hats, just not simultaneously!

The designer is other centered, and finds motivation and satisfaction in a relationship with a client or user to bring forth the work. That is not to say that artists cannot be designers, or that designers cannot rise to the level of fine artists. The results can be equally profound and far-reaching. This definition works for problem cases like the Diego Rivera mural—there was a client, but the mural was torn out because the work was ultimately Rivera’s own content, not a collaborative venture. It may be possible to categorically decide whether a given work is design or art; it may also be misleading.

Ultimately, if there needs to be a definition, placing a work somewhere on a continuum between art and design is rather more useful than a dichotomy. I remember Bucky Fuller saying “You can’t do everything, you have to decide where to invest your career time.” There are even lots of examples of people who were accomplished both as artists and designers—Le Corbusier, Leonardo, Bucky Fuller, Ray Eames, John Portman—it’s a long and interesting list. I decide that the conflict arises when I want to make design into art. One person can wear both hats, just not simultaneously! It is actually beneficial to do so, as each activity can enrich the creative approach of the other.

George Nelson’s 80-18-2 maxim: “You may have a hundred new ideas. Eighty have been done before. Eighteen are original but fall somewhere between mediocre and stupid. That leaves you with two good, original ideas! You have an obligation to use yourself up!”

Recognizing this fundamental difference, it then becomes crucial to apply George Nelson’s 80-18-2 maxim.

Aha. I have always felt that the language and tools of graphic design have vast untapped potential beyond what makes sense for client work. As a result of this brief encounter with Bass, my career focus sharpens. I resolve to apply Nelson’s Maxim to all my ideas, to be willing to wear two hats, and to always be conscious of which hat—my internally centered artist’s hat or my other-centered designer’s hat—is optimum for a given situation.

Sidney Topol: A Good Proposal on Time

Sidney Topol (1925– ) served in World War II, then received a BS in physics in 1947 from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He later attended the Harvard-MIT Radar School. Topol began his career with Raytheon Co., and went on to serve as president of Scientific Atlanta from 1971 to 1983, CEO from 1975 to 1987, and chairman of the board from 1978 to 1990. During his tenure, the company grew dramatically and developed the concept of cable/satellite connection, which established satellite-delivered television for the cable industry. He also played a key role in the development of international telecommunications trade policies.

He is the president of the Topol Group, a venture capital firm, and the founder of the Massachusetts Telecommunications Council. He is in the Cable Television Hall of Fame and the Georgia Technology Hall of Fame. He established the Sid and Libby Topol Scholarship and the Topol Distinguished Lecturer Series at UMass Amherst. He holds an honorary doctor of science degree from UMass.

1985–1991

I am asked to participate in a panel discussion about annual reports for the National Investor Relations Institute (NIRI). Each panelist is asked to look at several dozen annuals and give opinions about the relative merits of each, then discuss them in front of a NIRI audience and take questions. I try to be candid, and in doing so, I hit a few nerves. One of the annuals on which my candor falls particularly hard belongs to Scientific Atlanta, and the next day I get a call from their corporate secretary, Margaret Wilson Jones. To my surprise, she invites me to visit their office to discuss it further.

Aha: The goal of marketing, for the design professional, is to be hired for your expertise, in spite of your price, rather than the other way around!

Sidney Topol is a short, fit man with wavy hair and the aura of a superhero. His office is modest in size and furnishing, but there is a Kandinsky painting on the wall behind his desk. Introductions are brief and he notes the time on his watch.

“We are here to discuss?” he asks.

Jones starts, “This is the gentleman I told you about who...”

“Ripped up our annual report,” Topol says congenially.

She rejoins, “Well, I thought he would be a good choice because he had most of the same criticisms you did.”

Two of the criticisms on which we agree are a lack of continuity between the visuals and the narrative, and a lack of exciting imagery. Jones explains that there has never been a budget specifically for annual report photography, so they use what they can get from customers, which is uneven. I recommend that we take photographs of the most significant customer installations first, then build a narrative around that. Topol and Jones give me a quick list of a dozen such installations, and agree on a next meeting.

Driving back to the office, I realize that nobody at SA asked to see samples of our work, and we did not discuss budget, yet I had been hired. I flash back to my discovery of the Bertoli toggle, a decade before; I sense I have crossed another career boundary. For many years, I was selling from my portfolio and getting hired based on price, in spite of my expertise. Today, for the first time, I am hired for my expertise, without any portfolio. Pricing, though still important, comes later. The idea of the expertise-based sale comes alive.

We book an accomplished location photographer named Flip Chalfant and get him on the road. The team travels to several installations. I arrive in Topol’s office a month later with photographs representing six customers—no design or written content. I have brought contact sheets of a thousand photographs of SA customer equipment, and prints of fifty.

Jones says, “Don’t take the contact sheets to a CEO. He wants you to make the decisions. Just show him your best shots.”

“I get that from my engineers all the time—‘We can’t present yet, it isn’t finished.’ Over and over, I remind them: A good proposal on time is better than the perfect proposal too late!”

I take the photos to Topol, but I’m concerned—I tell him I would rather show them in the context of a design. Topol is studying the photographs intently, sorting them into groups. Without looking up, he says, “I get that type of comment from my engineers all the time—‘We can’t present yet, it isn’t finished.’ Over and over, I have to tell them: A good proposal on time is better than the perfect proposal too late!” Inside of a minute, he hands me back roughly a third of the photographs. “These ten pictures are brilliant. I want you to continue. Bring me twenty more images like these and we will make Scientific Atlanta a forty-dollar stock!”

“You have a sort of love-hate relationship with business details. Leaders have to be about big vision, shining a light far down the right path. You have to delegate the details or you never get out of the weeds. At the same time, you need details reported to you.”

The 1985 annual report for SA comes out, and looks great. Topol confides to me later, “When I handed this annual report out at the first analyst meeting of the year, I had them eating out of my hand!”

Almost immediately, we begin working on the next year’s annual. I’m with the photographer on location, documenting some large SA earth stations owned by one of the network affiliates. It’s cold, we are behind schedule, and we just need to take photographs and move on. The administrator of the installation is unhappy, and he decides to make an issue of it while we are there. He shows me several problems with his SA earth stations.

He says grimly, “I can’t get any response out of my field rep, and frankly, I will buy my next earth stations from another company.”

I’m about to say that this isn’t my area, and I’m just a contractor, but instinct speaks: “Here’s a major customer in a top-tier market, telling you the account is on the ropes. Do something!” It’s as though, standing there in the snow, a crevasse is opening before me; I must either fall in or jump. I have no authority to make promises—or do I? Jones said I had been “deputized.” As designers we make promises on behalf of our clients all the time. Making that relationship work in both directions feels risky, but it can be crucial to the success of the business. I look this distressed customer in the eye and promise to take his complaint to the top. A week later I relate this story to Topol. I hand him a few snapshots of the problem installation. Topol is silent, his jaw tense.

“I learned during our go-go growth years that my people would work tremendously hard and gladly let their leader have all the magazine covers and industry awards—as long as that leadership also takes the heat when things go wrong.”

I say, “I had no authority to promise him service, but the salesman in me wouldn’t let me sidestep such an obvious distress signal.”

“You did the right thing,” Topol reassures me. “I’m just concerned how I can get this fixed fast. The relationship—if we can save it—is worth many times your design fee.”

The next time I arrive at SA to sign in, the receptionist says, “Oh, Mr. Laufer, you are approved for an upper- level badge.” She hands me paperwork and sends me off to get security clearance and a mug shot. A simple act of salesmanship elevates my status within the organization. Design is valuable when designers do valuable things. Sometimes those valuable things are creative, but are not design.

Topol makes the transition to chairman and is getting ready to leave Atlanta and return to his beloved Boston. I have one lunch date open before he goes, so I ask him if he will give me some valedictory thoughts on leadership. He talks about the technical achievements that have propelled SA during his stewardship of the company, but I am interested in the how of his leadership.

He grasps this line of thinking instantly. “You have a sort of love-hate relationship with business details. Leaders have to be about big vision, overall direction. Shining a light far down the right path. You have to delegate the details or you never get out of the weeds. At the same time, you need details reported to you. You must have the confidence of and rapport with your direct reports, and foster a working chain of command. Where there is fear in the ranks, there’s a tendency to hide problems and failures from senior management—that can be catastrophic. I learned during our go-go growth years that my people would work tremendously hard and gladly let their leader have all the limelight—all the magazine covers and news clips and industry awards—as long as that leadership also takes the heat when things go wrong.”

We discuss the differences between leadership and management. Topol quotes the great management consultant and writer Peter Drucker: “Management is doing things right, leadership is doing the right things.”

“If you read the business magazines, it sounds as though entrepreneurship is all about boldly taking risk. The vision does indeed have to be bold, but to achieve it, your team has to work at minimizing risk, making small mistakes until you have all your systems working.”

Topol elaborates, “A lot of people can, with training and experience, do things right if you supply them with good objectives. Doing the right things, on the other hand, can be a lonely endeavor. If you read the business magazines, it sounds like entrepreneurship is all about boldly taking risk. I think it’s more about figuring out ways to minimize risk. The vision does indeed have to be bold, but to achieve it, your team has to make small, low-cost mistakes until you have your product working.”

Under the leadership of Topol, and later CEOs, SA does indeed return to profitable operation. Ten years after Topol’s retirement, the company is purchased by Cisco Systems for $43 a share—$3 per share more than Topol had promised himself at our first meeting!

Roberto Goizueta: Creative Friends

Roberto Goizueta (1931–1997) was born in Havana, Cuba. Goizueta was educated in a Jesuit college in Havana and graduated from Yale University in 1953 with a degree in chemical engineering. He responded to a want ad in Cuba seeking a bilingual chemical engineer, and in 1955 joined Coca-Cola, where he would remain for the rest of his career. He rose steadily, and emigrated to the US in 1960. Goizueta successfully managed many assignments during his career—he eventually became a protégé of Robert Woodruff—and held the offices of president, CFO, and vice chairman before becoming chairman in 1981. Goizueta’s leadership was characterized by bold moves. He spearheaded the development of Diet Coke, which succeeded spectacularly, but also introduced New Coke, which did not. He embraced Olympic sponsorship and opened new markets around the world. Under Goizueta’s leadership, Coca-Cola tripled in size and its stock price grew by 3,500 percent! Like his mentor, Goizueta was a generous benefactor to many causes, especially Emory University, which honored his contributions by adding his name to the Roberto C. Goizueta School of Business.

March 1993

Twenty years after I first stormed into Penn Station with The Great Midwest Mounted Valise, the dialogues continue. Giving and seeking mentoring becomes a pattern of life. Wearing two hats—fine art and graphic design—results in less income, but my design work benefits tremendously from my fine art exploration, and vice versa. My fine art projects, which allow the visual language of graphic design to take new directions, begin to find an audience in exhibitions and collections, but also result in design commissions that require more adventurous creative thought.

I take a page from Rand’s playbook, and use speaking and publishing as a way to stimulate the types of dialogues that result in business relations of trust and synergy. In early 1993, I put together an experimental lecture on spirituality in art. One such speaking engagement results in a call from the office of Roberto Goizueta, then the chairman of Coca-Cola. Mr. Goizueta, his assistant explains, has a special art need. Could I please come in to consult?

Goizueta’s friend, Don Keough, is about to retire as COO of Coca-Cola. Goizuetta wishes to give him a retirement gift. Keough is an art collector, so Goizueta wants to commission something to add to Keough’s collection to touch him personally—but, says the assistant, they need to know how to select it. The timing of my lecture and their need coincided, but just barely; the retirement party is in a few weeks! I’m traveling during much of that time, and Mr. G is available only seldom.

I suggest and get verbal approval for the idea of commissioning a painter to summarize Keough’s career in a lighthearted way. I make a few rough sketches in pencil for discussion.

Creative work isn’t made in a vacuum. It has to be about something. In a piece of fine art, the artist picks a subject, bringing the work forth from internally collected resources. In this case, the work is focused on a recipient, so the work is “other centered.” All my struggles with definitions are finally beginning to pay off! I request all the nonproprietary background on Mr. K’s career that can be had.

While that is being collected, I speak to a dozen artists’ representatives, scrambling to see who is available. We have a very tight time frame—and there is always a risk with commissioned work that the artwork may be rejected. I call my longtime ally Will Sumpter, who represents many artists. We settle on Drew Rose, a highly accomplished artist who meets our criteria and will have a lot of ideas.

Sumpter takes the box of Keough’s memorabilia with my idea sketches and goes off to brief Rose. Two days later, Sumpter calls to say he has sketches ready and is on his way to show them to me. Most top flight illustrators are fast, and Rose is exceptionally so, but this turnaround is very unexpected.

“Each step in the creative process involves a jump, like finding stepping stones across a stream. Those jumps that are familiar to us are unfamiliar to the C-suite, so a little forethought goes a long way.”

Sumpter explains, “Drew wants to be perfect for this, so he needs to save as much time for the finished art as possible.”

“Let me guess,” I say. “Drew worked on it for forty hours straight and he’s sleeping now.” Sumpter smiles. This goes against Don Trousdell’s 80/20 observation, but this is a rather unique situation!