Chapter 2

Story Basics

A story is the narrative, or telling, of an event or series of events, crafted in a way to interest the audience members, whether they are readers, listeners, or viewers. At its most basic, a story has a beginning, middle, and end. It has compelling characters (or questions), rising tension, and conflict that reaches some sort of resolution. It engages the audience on an emotional and intellectual level, motivating viewers to want to know what happens next.

Don’t be confused by the fact that festivals and film schools commonly use the term narrative to describe only works of dramatic fiction. Most documentaries are also narrative, which simply means that they tell stories (whether or not those stories are also narrated is an entirely different issue). How they tell those stories, and which stories they tell, are part of what separates these films into subcategories of genre or style, from cinéma vérité to film noir.

Efforts to articulate the basics of good storytelling are not new. The Greek philosopher Aristotle first set out guidelines for what his analysis revealed as a “well-constructed plot” in 350 BCE, and these have been applied to storytelling—onstage, on the page, and on screen— ever since. Expectations about how storytelling works seem hardwired in audiences, and meeting, confounding, and challenging those expectations is no less important to the documentarian than it is to the dramatist.

Some Storytelling Terms

Exposition

Exposition is the information that grounds you in a story: who, what, where, when, and why. It gives audience members the tools they need to follow the story that’s unfolding and, more importantly, it allows them inside the story. But exposition should not be thought of as something to “get out of the way.” Too often, programs are front-loaded with information that audiences don’t yet need to know, including backstory. The problem is that when audiences do need this information, they won’t remember it, and in the meantime, the film seems dull and didactic.

Films may start with a bit of establishing information, conveyed through narration, interviews, or text on screen (look at the openings of Control Room and Jonestown, for example). But this information should offer the minimum necessary—just enough to get the story under way. After that, the trick is to reveal exposition when it best serves that story, whether by raising the stakes, advancing our understanding of character, or anticipating and addressing potential confusion.

Good exposition is a way to build suspense and motivate audiences to stay with you. Noted filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock once explained suspense in this way: Suppose audiences are watching a scene in which people are seated at a table, with a clock nearby, talking casually. Suddenly a bomb beneath the table explodes. The viewers are shocked, of course. But suppose that audiences had previously seen a character put a bomb into a briefcase, set it to go off at a specific time, and then place the briefcase under the table. The people sitting and chatting are unaware of the danger, but the audience is tense as it watches the clock, knowing what’s coming. In the first scenario, Hitchcock noted, there are several seconds of shock. In the second, there are several minutes of suspense.

Watch films that you enjoy and pay attention not only to what you know, but as importantly, when you learn it. This is true of present-day details and of backstory; if the backstory matters, you want to present it when it when the audience is motivated to hear it. Also pay attention to the many ways in which filmmakers convey information. Sometimes it’s revealed when the people you’re filming argue: “Yeah? Well, we wouldn’t even be in this mess if you hadn’t decided to take your paycheck to Vegas!” Sometimes it’s revealed through headlines or other printed material. Good narration can deftly weave exposition into a story, filling in gaps as needed; voice-over material drawn from interviews can sometimes do the same thing. Exposition can also be handled through visuals: an establishing shot of a place or sign; footage of a sheriff nailing an eviction notice on a door (Roger & Me); the opening moments of an auction (Troublesome Creek). Toys littered on a suburban lawn say “Children live here.” Black bunting and a homemade shrine of flowers and cards outside a fire station say “Tragedy has occurred.” A long shot of an elegantly-dressed woman in a large, spare office high up in a modern building says “This woman is powerful.” A man on a subway car reading an issue of The Boston Globe tells us where we are, as would a highway sign or a famous landmark— the Eiffel Tower, for example. Time-lapse photography, title cards, and animation can all be used to convey exposition, sometimes with the added element of humor or surprise—think of the cartoons in Super Size Me.

Offered at the right time, exposition enriches our understanding of characters and raises the stakes in their stories. Watch Daughter from Danang and pay attention to when we learn that Heidi Bub’s birth father was an American soldier, for example; that her birth mother’s husband was fighting for the Viet Cong; and that Heidi’s adoptive mother has stopped communicating with her. These details add to our understanding of who these characters are and why they do what they do, and the information is effective because of the careful way it’s seeded throughout the film.

Theme

In literary terms, theme is the general underlying subject of a specific story, a recurring idea that often illuminates an aspect of the human condition. Eyes on the Prize, in 14 hours, tells an overarching story of America’s civil rights struggle. The underlying themes include race, poverty, and the power of ordinary people to accomplish extraordinary change. Themes in The Day after Trinity, the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s development of the atomic bomb, include scientific ambition, the quest for power, and efforts to ensure peace and disarmament when it may be too late.

“Theme is the most basic lifeblood of a film,” says filmmaker Ric Burns. “Theme tells you the tenor of your story. This is what this thing is about.” Burns chose to tell the story of the ill-fated Donner Party and their attempt to take a shortcut to California in 1846 not because the cannibalism they resorted to would appeal to prurient viewers, but because their story illuminated themes and vulnerabilities in the American character. These themes are foreshadowed in the film’s opening quote from Alexis de Tocqueville, a French author who toured the United States in 1831. He wrote of the “feverish ardor” with which Americans pursue prosperity, the “shadowy suspicion that they may not have chosen the shortest route to get it,” and the way in which they “cleave to the things of this world,” even though death steps in, in the end. These words presage the fate of the Donner Party, whose ambitious pursuit of a new life in California will have tragic consequences.

Themes may emerge from the questions that initially drove the filmmaking. On one level, My Architect is about a middle-aged filmmaker’s quest to know the father he lost at the age of 11, some 30 years before. But among the film’s themes are impermanence and legacy. Kahn says in bonus material on the film’s DVD:

You sort of wonder, “After we’re gone, what’s left?” How much would I really find of my father out there? . . . I know there are buildings. But how much emotion, how much is really left? And I think what really kind of shocked me is how many people are still actively engaged in a relationship with him. They talk to him as if he’s still here. They think of him every day. In a way I find that very heartening.

Understanding your theme(s) can help you determine both what and how you shoot. Renowned cinematographer Jon Else explains his thinking as he planned to shoot workers building a trail at Yosemite National Park for his film Yosemite: The Fate of Heaven.

What is this shot or sequence telling us within the developing narrative of this film, and what is this shot or sequence telling us about the world? . . . Are we there with the trail crew and the dynamite because it’s dangerous? Are we there because all the dynamite in the world is not going to make a bit of difference in this giant range of mountains, where people are really insignificant? Are we there because these people are underpaid and they’re trying to unionize?

Else offers examples of how different answers might change the shooting:

If the scene was about the camaraderie between the members of the trail crew, all of whom had lived in these mountains together, in camp, for many months by that time, you try to do a lot of shots in which the physical relationship between people shows.

. . . They weren’t trying to unionize, but if, in fact, we had been doing a sequence about the labor conditions for trail workers in Yosemite, we probably would have made it a point to shoot over the course of a long day, to show how long the day was, show them eating three meals on the trail, walking home really bone-tired in the dark. Basically, the more you’re aware of what you want these images to convey, the richer the images are going to be.

Filmmaker Sam Pollard (August Wilson: The Ground on Which I Stand), a professor at New York University, says that for student filmmakers:

The biggest pitfall is understanding what their film’s about right from the beginning. Before they sit down to write a page of the narration or script, what’s the theme? And then on the theme, what’s the story that they’re going to convey to get across the theme?

Arc

The arc refers to the way or ways in which the events of the story transform your characters. An overworked executive learns that his family should come first; a mousy secretary stands up for himself and takes over the company; a rag-tag group of unlikely kids wins the national chess tournament. In pursuing a goal, protagonists learn something about themselves and their place in the world, and those lessons change them—and may, in fact, change their desire for the goal.

In documentary films, story arcs can be hard to find. Never, simply in the interest of a good story, presume to know what a character is thinking or feeling, or present a transformation that hasn’t occurred. If there is change, you will discover it through solid research and multiple strands of verifiable evidence. For example, in The Day after Trinity, physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, a left-leaning intellectual, successfully develops the world’s first nuclear weapons and is then horrified by the destructive powers he’s helped to unleash. He spends the rest of his life trying to stop the spread of nuclear weapons and in the process falls victim to the Cold War he helped to launch; once hailed as an American hero, he is accused of being a Soviet spy.

In The Thin Blue Line, we hear and see multiple versions of a story that begins when Randall Adams’s car breaks down on a Saturday night and a teenager named David Harris offers him a ride. Later that night, a police officer is shot and killed by someone driving Harris’s car, and Adams is charged with the murder. The deeper we become immersed in the case, the more clearly we see that Adams’s imprisonment and subsequent conviction are about politics, not justice. He is transformed from a free man to a convicted felon, and that transformation challenges the viewer’s assumptions about justice and the basic notion that individuals are innocent until proven guilty.

In Murderball, a documentary about quadriplegic athletes who compete internationally in wheelchair rugby, a few characters undergo transformations that together complement the overall film. There’s Joe Soares, a hard-driving American champion now coaching for Canada, whose relationship with his son changes noticeably after he suffers a heart attack. Player Mark Zupan comes to terms with the friend who was at the wheel during the accident in which he was injured. And Keith Cavill, recently injured, adjusts to his new life and even explores wheelchair rugby. All of these transformations occurred over the course of filming, and the filmmakers made sure they had the visual material they needed to show them in a way that felt organic and unforced.

Plot and Character

Films are often described as either plot- or character-driven. A character-driven film is one in which the action of the film emerges from the wants and needs of the characters. In a plot-driven film, the characters are secondary to the events that make up the plot. (Many thrillers and action movies are plot-driven.) In documentary, both types of films exist, and there is a lot of gray area between them. Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line imitates a plot-driven noir thriller in its exploration of the casual encounter that leaves Randall Adams facing the death penalty. Circumstances act upon Adams; he doesn’t set the plot in motion except inadvertently, when his car breaks down and he accepts a ride from David Harris. In fact, part of the film’s power comes from Adams’s inability to alter events, even as it becomes apparent that Harris, not Adams, is likely to be the killer.

From Waltz with Bashir. Photo courtesy Bridget Folman Film Gang.

Some films are clearly character-driven. Daughter from Danang, for example, is driven by the wants of its main character, Heidi Bub, who was born in Vietnam and given up for adoption. Raised in Tennessee and taught to deny her Asian heritage, Bub is now estranged from her adoptive mother. She sets the events of the film in motion when she decides to reunite with her birth mother. Similarly, in Waltz with Bashir, Israeli filmmaker Ari Folman sets events in motion when he decides to look back at a past he cannot remember.

As mentioned, the difference between plot- and character-driven films can be subtle, and one often has strong elements of the other. The characters in The Thin Blue Line are distinct and memorable; the plot in both Daughter from Danang and Waltz with Bashir is strong and takes unexpected turns. It’s also true that plenty of memorable documentaries are not “driven” at all in the Hollywood sense. When the Levees Broke, a four-hour documentary about New Orleans during and after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, generally follows the chronology of events that devastated a city and its people. As described by Sam Pollard, the film’s supervising editor and co-producer, there is a narrative arc to each hour and to the series. But the complexity of the four-hour film and its interweaving of dozens of individual stories, rather than a select few, differentiate it from a more traditional form of narrative.

Some shorter films present a “slice of life” portrait of people or places. With longer films, however, there generally needs to be some overarching structure. Frederick Wiseman’s documentaries are elegantly structured but not “plotted” in the sense that each sequence makes the next one inevitable, but there is usually an organizing principle behind his work, such as a “year in the life” of an institution. Still other films are driven not by characters or plot but by questions, following an essay-like structure; examples include Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 and Daniel Anker’s Imaginary Witness: Hollywood and the Holocaust, discussed by Susan Kim in Chapter 16. Many films merge styles: Super Size Me is built around the filmmaker’s 30-day McDonald’s diet, but to a large extent the film is actually driven by a series of questions, making it an essay. This combination of journey and essay can also be found in Nathaniel Kahn’s My Architect. Virunga combines several types of filmmaking, as discussed by Orlando von Einsiedel in Chapter 22.

Point of View

Point of view describes the perspective, or position, from which a story is told. This can be interpreted in a range of ways. For example, point of view may describe the character through whom you’re telling a story. Imagine telling the story of Goldilocks and the three bears from the point of view of Goldilocks, and then retelling it from the point of view of Papa Bear. Goldilocks might tell you the story of a perfectly innocent child who was wandering through the woods when she became hungry, ventured into an apparently abandoned house, and found herself under attack by bears. In contrast, Papa Bear might tell you the story of an unwanted intruder.

By offering an unexpected point of view, filmmakers can sometimes force viewers to take a new look at a familiar subject. For example, Jon Else’s Sing Faster: The Stagehands’ Ring Cycle documents a performance by the San Francisco Opera of Richard Wagner’s Ring cycle from the point of view of the union stagehands behind the scenes.

Point of view can also be used to describe the perspective of the camera, including who’s operating it and from what vantage point. Much of Deborah Scranton’s The War Tapes, for example, was filmed by the soldiers themselves, rather than by camera crews following the soldiers. Point of view can also refer to the perspective of time and the lens through which an event is viewed. As one example, The War Tapes looks at the aftermath of a car bombing outside Al Taji through footage of the event as it unfolds (from the camera operated by Sgt. Steve Pink, who was there); an interview with Pink conducted within 24 hours of the event by Spc. Mike Moriarty; audio from an interview Scranton conducted with Pink in the months after he returned to the United States; and Pink in voice-over, reading (after he had returned home) from a journal he kept while he was in Iraq. “So it’s all layered in there, this multi-faceted perception of that event,” Scranton explains in Chapter 20.

There is also, of course, “point of view” of the filmmaker and/or filmmaking team.

Detail

Detail encompasses a range of things that all have to do with specificity. First, there is what’s known as the “telling detail.” A full ashtray next to a bedridden man would indicate that either the man or a caregiver is a heavy smoker. The choice of what to smoke, what to drink, when to drink it (whisky for breakfast?), what to wear, how to decorate a home or an office or a car, all provide clues about people. They may be misleading clues: That African artwork may have been left behind by an old boyfriend, rather than chosen by the apartment renter; the expensive suit may have been borrowed for the purpose of the interview. But as storytellers, our ears and eyes should be open to details, the specifics that add layers of texture and meaning. We also need to focus on detail if we write narration. “The organization grew like wildfire” is clichéd and meaningless; better to provide evidence: “Within 10 years, an organization that began in Paris with 20 members had chapters in 12 nations, with more than 2,500 members worldwide.”

In Hollywood Terms: A "Good Story Well Told"

In their book, The Tools of Screenwriting, authors David Howard and Edward Mabley stress that a story is not simply about somebody experiencing difficulty meeting a goal; it’s also “the way in which the audience experiences the story.” The elements of a “good story well told,” they write, are:

- This story is about somebody with whom we have some empathy.

- This somebody wants something very badly.

- This something is difficult, but possible, to do, get, or achieve.

- The story is told for maximum emotional impact and audience participation in the proceedings.

- The story must come to a satisfactory ending (which does not necessarily mean a happy ending).

Although Howard and Mabley’s book is directed at dramatic screenwriters, who are free to invent not only characters but also the things that they want and the things that are getting in the way, this list is useful for documentary storytellers. Your particular film subject or situation might not fit neatly within these parameters, however, so further explanation follows.

Who (or What) the Story Is About

The somebody is your protagonist, your hero, the entity whose story is being told. Note that your hero can, in fact, be very “unheroic,” and the audience might struggle to empathize with him or her. But the character and/or character’s mission should be compelling enough that the audience cares about the outcome. In The Execution of Wanda Jean, for example, Liz Garbus offers a sympathetic but unsparing portrait of a woman on death row for murder. You also may have multiple protagonists, as was the case in Spellbound.

The central character doesn’t necessarily need to be a person. In Ric Burns’s New York, a seven-episode history, the city itself is the protagonist, whose fortunes rise and fall and rise over the course of the series. (Throughout that series, however, individual characters and stories come to the fore.) But often, finding a central person through whom to tell your story can make an otherwise complex topic more manageable and accessible to viewers. For I’ll Make Me a World, a six-hour history of African-American arts in the twentieth century, producer Denise Greene explored the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s by viewing it through the eyes and experience of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks, an established, middle-aged author whose life and work were transformed by her interactions with younger artists responding to the political call for Black Power.

What the Protagonist Wants

The something that somebody wants is also referred to as a goal or an objective. In Blue Vinyl, filmmaker Judith Helfand sets out, on camera, to convince her parents to remove the new siding from their home. Note that a filmmaker’s on-screen presence doesn’t necessarily make him or her the protagonist. In Steven Ascher and Jeanne Jordan’s Troublesome Creek: A Midwestern, the filmmakers travel to Iowa, where Jeanne’s family is working to save their farm from foreclosure. Jeanne is the film’s narrator and she can be seen in the footage, but the protagonists are her parents, Russel and Mary Jane Jordan. It’s their goal—to pay off their debt by auctioning off their belongings—that drives the film’s story.

Active versus Passive

Storytellers speak of active versus passive goals and active versus passive heroes. In general, you want a story’s goals and heroes to be active, which means that you want your story’s protagonist to be in charge of his or her own life: To set a goal and then to go about doing what needs to be done to achieve it. A passive goal is something like this: A secretary wants a raise in order to pay for a trip to Europe. She is passively waiting for the raise, hoping someone will notice that her work merits reward. To be active, she would have to do something to ensure that she gets that raise, or she would have to wage a campaign to raise the extra money she needs for the trip, such as taking a second job.

An exception is when the passivity is the story. In The Thin Blue Line, for example, Randall Adams, locked up on death row, is a passive protagonist because he can’t do anything to free himself, as no one believes him when he claims to be innocent. In general, though, you want your protagonist to be active, and you want him or her to have a goal that’s worthy. In the example of the secretary, will an audience really care whether or not she gets the trip? Probably not. If we had a reason to be sympathetic—she is visiting her estranged family, for example—maybe we would care, but it’s not a very strong goal. Worthy does not mean a goal has to be noble—it doesn’t all have to be about ending world hunger or ensuring world peace. It does have to matter enough to be worth committing significant time and resources to. If you only care a little about your protagonists and what they want, your financiers and audience are likely to care not at all.

Difficulty and Tangibility

The something that is wanted—the goal—must be difficult to do or achieve. If something is easy, there’s no tension, and without tension, there’s little incentive for an audience to keep watching. Tension is the feeling we get when issues or events are unresolved, especially when we want them to be resolved. It’s what motivates us to demand, “And then what happens? And what happens after that?” We need to know, because it makes us uncomfortable not to know. Think of a movie thriller in which you’re aware, but the heroine is not, that danger lurks in the cellar. As she heads toward the steps, you feel escalating tension because she is walking toward danger. If you didn’t know that the bad guy was in the basement, she would just be a girl heading down some stairs. Without tension, a story feels flat; you don’t care one way or the other about the outcome.

So where do you find the tension? Sometimes, it’s inescapable, as is the case with the National Guardsmen enduring a year-long tour of duty in Iraq, in Deborah Scranton’s The War Tapes. Sometimes, tension comes from conflict between your protagonist and an opposing force, whether another person (often referred to as the antagonist or opponent), a force of nature, society, or the individual (i.e., internal conflict). In Barbara Kopple’s Harlan County, U.S.A ., striking miners are in conflict with mine owners. In Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady’s The Boys of Baraka, the tension comes from knowing that the odds of an education, or even a future that doesn’t involve prison or death, are stacked against a group of African-American boys from inner-city Baltimore. When a small group of boys is given an opportunity to attend school in Kenya as a means of getting fast-tracked to better high schools in Baltimore, we want them to succeed and are devastated when things seem to fall apart. In Born into Brothels, similarly, efforts to save a handful of children are threatened by societal pressures (including not only economic hardship but also the wishes of family members who don’t share the filmmakers’ commitment to removing children from their unstable homes), and by the fact that the ultimate decision makers, in a few cases, are the children themselves. The audience experiences frustration—and perhaps recognition—as some of these children make choices that in the long run are likely to have significant consequences.

Note that conflict can mean a direct argument between two sides, pro and con (or “he said, she said”). But such an argument sometimes weakens tension, especially if each side is talking past the other or if individuals in conflict have not been properly established to viewers. If we don’t know who’s fighting or what’s at stake for the various sides, we won’t care about the outcome. On the other hand, if the audience goes into an argument caring about the individuals involved, especially if they care about all the individuals involved, it can lead to powerful emotional storytelling. Near the end of Daughter from Danang, for example, the joyful reunion between the American adoptee and her Vietnamese family gives way to feelings of anger and betrayal brought on by the family’s request for money. The palpable tension the audience feels stems not from taking one side or another in the argument, but from empathy for all sides.

Weather, illness, war, self-doubt, inexperience, hubris—all of these can pose obstacles as your protagonist strives to achieve his or her goal. And just as it can be useful to find an individual (or individuals) through whom to tell a complex story, it can be useful to personify the opposition. Television viewers in the 1960s, for example, at times seemed better able to understand the injustices of southern segregation when reporters focused on the actions of individuals like Birmingham (Alabama) Police Chief Bull Connor, who turned police dogs and fire hoses on young African Americans as they engaged in peaceful protest.

Worthy Opponent

Just as you want your protagonist to have a worthy goal, you want him or her to have a worthy opponent. A common problem for many filmmakers is that they portray opponents as one-dimensional; if their hero is good, the opponent must be bad. In fact, the most memorable opponent is often not the opposite of the hero, but a complement to him or her. In the film Sound and Fury, young Heather’s parents oppose her wishes for a cochlear implant not out of malice but out of their deep love for her and their strong commitment to the Deaf culture into which they and their daughter were born. Chicago Mayor Richard Daley was a challenging opponent for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in Eyes on the Prize specifically because he wasn’t Bull Connor; Daley was a savvy northern politician with close ties to the national Democratic Party and a supporter of the southern-based civil rights movement. The story of his efforts to impede Dr. King’s campaign for open housing in Chicago in 1966 proved effective at underscoring the significant differences between using nonviolence as a strategy against de jure segregation in the South and using it against de facto segregation in the North.

As stated earlier, it’s important to understand that you should not in any way be fictionalizing characters who are real human beings. (The rules for documentary are different than those for reality television, where content and characters may be manipulated for entertainment purposes, depending on the releases signed by participants.) With documentary work, you are evaluating a real situation from the perspective of a storyteller, and working with what is actual and defensible. If there is no opponent, you can’t manufacture one. Mayor Daley, historically speaking, was an effective opponent. Had he welcomed King with open arms and been little more than an inconvenience to the movement, it would have been dishonest to portray him as a significant obstacle.

Tangible Goal

Although difficult, the goal should be possible to do or achieve, which means that it’s best if it’s both concrete and realistic. “Fighting racism” or “curing cancer” or “saving the rainforest” may all be worthwhile, but none is specific enough to serve as a story objective. In exploring your ideas for a film, follow your interests, but then seek out a specific story to illuminate them. The Boys of Baraka is clearly an indictment of racism and inequality, but it is more specifically the story of a handful of boys and their enrollment in a two-year program at a tiny school in Kenya. Born into Brothels illuminates the difficult circumstances facing the children of impoverished sex workers in Kolkata, but the story’s goals are more tangible. Initially, we learn that filmmaker Zana Briski, in Kolkata to photograph sex workers, has been drawn to their children. “They wanted to learn how to use the camera,” she says in voiceover. “That’s when I thought it would be really great to teach them, and to see this world through their eyes.” Several minutes later, a larger but still tangible goal emerges: “They have absolutely no opportunity without education,” she says. “The question is, can I find a school— a good school—that will take kids that are children of prostitutes?” This, then, becomes the real goal of the film, one enriched by the children’s photography and exposure to broader horizons.

Note also that the goal is not necessarily the most “dramatic” or obvious one. In Kate Davis’s Southern Comfort, a film about a transgender male dying of ovarian cancer, Robert Eads’s goal is not to find a cure; it’s to survive long enough to attend the Southern Comfort Conference in Atlanta, a national gathering of transgender people, with his girlfriend, Lola, who is also transgender.

Emotional Impact and Audience Participation

The concept of telling a story for greatest emotional impact and audience participation is perhaps the most difficult. It’s often described as “show, don’t tell,” which means that you want to present the evidence or information that allows viewers to experience the story for themselves, anticipating twists and turns and following the story line in a way that’s active rather than passive. Too often, films tell us what we’re supposed to think through the use of heavy-handed narration, loaded graphics, or a stacked deck of interviews.

Think about the experience of being completely held by a good mystery. You aren’t watching characters on screen; you’re right there with them, bringing the clues you’ve seen so far to the story as it unfolds. You lose track of time as you try to anticipate what happens next, who will do what, and what will be learned. It’s human nature to try to make sense of the events we’re confronted with, and it’s human nature to enjoy being stumped or surprised. In Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, you think Enron’s hit bottom, that all the price manipulation has finally caught up with them and they’ll be buried in debt—until someone at Enron realizes that there’s gold in California’s power grid.

Telling a story for emotional impact means that the filmmaker is structuring the story so that the moments of conflict, climax, and resolution—moments of achievement, loss, reversal, etc.—adhere as well as possible to the internal rhythms of storytelling. Audiences expect that the tension in a story will escalate as the story moves toward its conclusion; scenes tend to get shorter, action tighter, the stakes higher. As we get to know the characters and understand their wants and needs, we care more about what happens to them; we become invested in their stories. Much of this structuring takes place in the editing room. But to some extent, it also takes place as you film, and planning for it can make a difference. Knowing that as Heidi Bub got off the airplane in Danang she’d be greeted by a birth mother she hadn’t seen in 20 years, what preparations did the filmmakers need to make to be sure they got that moment on film? What might they shoot if they wanted to build up to that moment, either before or after it actually occurred? (They shot an interview with Heidi and filmed her, a “fish out of water,” as she spent a bit of time in Vietnam before meeting with her mother.) In the edited film, by the time Heidi sees her mother, we realize (before she does) how fully Americanized she’s become and how foreign her family will seem. We also know that the expectations both she and her birth mother have for this meeting are very high.

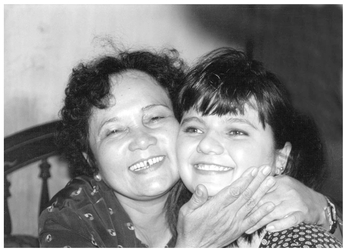

Mai Thi Kim and her daughter, Heidi Bub, in Daughter from Danang. Photo courtesy of the filmmakers.

You want to avoid creating unnecessary drama—turning a perfectly good story into a soap opera. There’s no reason to pull in additional details, however sad or frightening, when they aren’t relevant. If you’re telling the story of a scientist unlocking the genetic code to a certain mental illness, for example, it’s not necessarily relevant that she’s also engaged in a custody battle with her former husband, even if this detail seems to spice up the drama or, you hope, make the character more “sympathetic.” If the custody battle is influenced by her husband’s mental illness and her concerns that the children may have inherited the disease, there is a link that could serve the film well. Otherwise, you risk adding a layer of detail that detracts, rather than adds.

False emotion—hyped-up music and sound effects and narration that warns of danger around every corner—is a common problem, especially on television. As in the story of the boy who cried wolf, at some point it all washes over the viewer like so much noise. If the danger is real, it will have the greatest storytelling impact if it emerges organically from the material.

Raising the Stakes

Another tool of emotional storytelling is to have something at stake and to raise the stakes until the very end. Look at the beginning of Control Room. The film intercuts story cards (text on screen) with images of everyday life. The cards read: March 2003 / The United States and Iraq are on the brink of war. / Al Jazeera Satellite Channel will broadcast the war . . . / to forty million Arab viewers. / The Arab world watches . . . / and waits. / CONTROL ROOM. Clearly, these stakes are high.

In the hands of a good storyteller, even small or very personal stakes can be made large when their importance to those in the story is conveyed. For example, how many people in the United States—or beyond, for that matter—really care who wins or loses the National Spelling Bee, held each year in Washington, D.C.? But to the handful of children competing in Spellbound, and to their families and communities, the contest is all-important. Through skillful storytelling, the filmmakers make us care not only about these kids but about the competition, and as the field narrows, we can’t turn away.

Stakes may rise because (genuine) danger is increasing or time is running out. In Sound and Fury, for example, the stakes rise as time passes, because for a child born deaf, a cochlear implant is most effective if implanted while language skills are being developed. How do the filmmakers convey this? We see Heather’s much younger cousin get the implant and begin to acquire spoken-language skills; we also learn that Heather’s mother, born deaf, might now get little benefit from the device. As Heather enrolls in a school for the deaf without getting an implant, we understand that the decision has lifelong implications.

In terms of your role as the storyteller, stakes also rise because of the way you structure and organize your film: What people know, and when they know it, what the stakes of a story mean to your characters and how well you convey that—all of these play a role in how invested the audience becomes in wanting or even needing to know the outcome of your film.

A Satisfactory Ending

A satisfactory ending, or resolution, is often one that feels both unexpected and inevitable. It must resolve the one story you set out to tell. Say you start the film with a problem: A little girl has a life-threatening heart condition for which there is no known surgical treatment. Your film then goes into the world of experimental surgery, where you find a charismatic doctor whose efforts to solve a very different medical problem have led him to create a surgical solution that might work in the little girl’s situation. To end on this surgical breakthrough, however, won’t be satisfactory. Audiences were drawn into the story of the little girl, and this surgeon’s work must ultimately be related to that story. Can his work make a difference in her case? You need to complete the story with which the film began. With that said, there is never just one correct ending.

Suppose, for example, that your film is due to be aired months before the approval is granted that will allow doctors to try the experimental surgery on the girl. Make that your ending, and leave the audience with the knowledge that everyone is working to ensure that she will survive until then. Or perhaps the surgery is possible, but at the last minute the parents decide it’s too risky. Or they take that risk, and the outcome is positive. Or negative. Or perhaps the doctor’s breakthrough simply comes too late for this one child but may make a difference for hundreds of others. Any of these would be a satisfactory ending, provided it is factual. It would be unethical to manipulate the facts to imply a “stronger” or more emotional ending that misrepresents what you know the outcome to be. Suppose, for example, that the parents have already decided that no matter how much success the experimental work is having, they will not allow their daughter to undergo any further operations. You cannot imply that this remains an open question (e.g., with a teaser such as “Whether the operation will save the life of little Candy is yet to be seen.”).

Ending a film in a way that’s satisfying does not necessitate wrapping up all loose ends or resolving things in a way that’s upbeat. The end of Daughter from Danang is powerful precisely because things remain unsettled; Heidi Bub has achieved the goal of meeting her birth mother, but even two years after her visit, she remains deeply ambivalent about continued contact. At the end of The Thin Blue Line, Randall Adams remains a convicted murderer on death row, even as filmmaker Errol Morris erases any lingering doubts the audience might have as to his innocence.

Sources and Notes

There are various versions of this Alfred Hitchcock story distinguishing shock and suspense, including a discussion at the American Film Institute in 1972, http://the.hitchcock.zone/wiki/Alfred_Hitchcock_at_the_AFI_Seminar_roundtable(18/Aug/1972). Story elements from David Howard and Edward Mabley, The Tools of Screenwriting (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993). As described in a follow-up film, Sound and Fury: Six Years Later, Heather Artinian eventually received the cochlear device. Information about her work as an advocate for the hearing impaired can be found online. The Thin Blue Line’s Randall Adams was released in 1989, following the film’s release. Information about his case can be found online.