Chapter 7

Close Viewing

Audiences often respond to documentary work primarily in terms of its content or issues raised. In some ways, this is a mark of success, in the same way that people binge-watching a television drama may not take the time to notice how carefully the various subplots were constructed over an entire season, or how readers of a terrific mystery novel race through the pages to find out who did it. Done well, craft should feel inevitable, seamless, and invisible. Characters are simply alive; the flow of ideas and plot feels organic; the argument seems well-built and earned.

But people who want to write novels or episodic television or documentaries need to figure out how that success was achieved. This chapter offers several ways to analyze documentary films as a way of letting those films’ creators—the team of people behind their production—teach you themselves.

Watching the Film

What follows are some exercises for watching the film closely. You can either watch the film all the way through without stopping and then go back and start to watch more closely from the beginning, or you can watch closely from the start. (You’ll need to view the film on a device that allows you to pause and to keep track of running time.) The benefit of starting and stopping on the first time through is that you have no preconceived notions as you pause at various points to ask questions such as: At this point in the film, what do I think it’s about? Who or what am I concerned for? What’s at stake? Where do I think the story is headed?

If instead you watch the film first without interruptions, be sure to take a moment before starting again to ask yourself some general questions such as: What was the film’s train? How did the film begin? Did parts of this film drag or seem particularly strong? What’s the film’s central argument? Then, when you watch the film again more slowly, you’ll have a sense of how your impressions align with or contradict what you’re discovering about the film’s story and structure.

The Opening Sequence

The opening sequence, beginning with the film’s first frame, may be as short as a minute or as long as 10 minutes; each film is different. But in general, this opening sequence contains the DNA of the entire film to come. It sets out the promise between filmmaker and audience, making clear at least some of the film’s rules of engagement, such as what the film is about, how the story will be told, with what elements the story will be told, and why it matters—why this film is worth an audience’s time and attention.

The opening sequence is the first full sequence in the film, starting from the first frame. After you’ve watched this sequence, ask yourself some questions, such as:

- What do I think this film is about?

- Where do I think this film is headed?

- What would I say are the top three to five “bullet points” that the filmmaker has used to grab my attention and immerse me in the film, making me want to watch?

Looking at a range of opening sequences can be very useful: first, because there are common storytelling strategies achieved in the way a film opens; and second, because despite this, they can still be very different from each other, each uniquely creative.

Virunga

At the first frame of action, we enter with a group of men in uniform; it’s revealed that they are part of a funeral procession. The scene is vérité; there is no text or voice-over to place us. At the graveside, a man speaks: “Protect us, and help us to account for each day of our lives.” In voice-over, we hear another man: “Oh, Congo. Our dear Ranger Kaserka died trying to rebuild this country.” As we leave the gravesite, the unaccompanied singing of the mourners gives way to recorded music and the film cuts (about 1:25) to aerial footage traveling low along a river. This image becomes black and white, giving way to carefully selected archival imagery, including footage, a map, and stills. Over these visuals, with the theme song continuing, the filmmakers add 13 blocks of text that gives the viewer historical and thematic context. These bring us from 1885 (“Africa carved into colonies ruled by European nations”) to 2003 (“First democratic elections in 40 years.”)

At about 3:40, over a shot of people lined up to vote, the film dissolves back to an aerial over water, then tilts up to reveal mountains. A new series of lower thirds begins, over present-day footage:

- 2010: Oil discovery claimed in eastern Congo under Lake Edward in Virunga National Park.

- A home to thousands of people and the last mountain gorillas.

- 2012: Instability returns.

At about 4:40, another aerial follows a small plane over a field in which we see rangers patrolling. (The film title comes up, and then the opening sequence, including the music, ends.) The film moves into a new, second sequence.

To summarize: In less than five minutes, the opening of Virunga has set forth where we are, why we’re there, what the problem is, and its deep historical precedent. We don’t know everything, and that’s as it should be. Virunga, like any good film, unfolds over time. It asks the audience to work as they watch, making connections, seeing irony, coming to realizations. We’ve seen a range of compelling, disturbing, and breathtaking footage.

In terms of film storytelling, it’s useful to note that the film did not start “the beginning,” with archival images and data about 1885—that would have been dull, because we’re not motivated to care. It started with vérité footage of a funeral, a decision director Orlando von Einsiedel discusses in Chapter 22. The scene lasts about a minute and a half, and raises questions: In Congo, a man has died “trying to rebuild this country.” Why does it need rebuilding? Why are people being killed for their efforts? Who are these men in their uniforms, carrying guns?

The aerial along the water breaks us out of the funeral scene and brings us into the historical montage, which as noted runs from 1885 to the elections in 2006. Another aerial breaks this up, which has the effect of drawing additional attention to a newer, current threat (which will turn out to be a focus of this film): the discovery of oil under Lake Edward. The montage continues, but it’s more localized now, and we move closer to the communities at risk, and learn that instability has returned. This is the film’s launching point.

Super Size Me

Like Virunga, Morgan Spurlock’s Super Size Me packs a lot of basic exposition into the film’s opening sequence, but the films are, of course, very different. In this film, at the first frame of action we see a group of children singing a song that invokes the names of fast-food restaurants, to humorous effect. For the purpose of analysis, I’ve broken what follows into a series of “idea” beats:

- Following a text-on-screen quote from McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc, a professional-sounding narrator (who turns out to be Morgan Spurlock) tells us that “everything’s bigger in America.”

- In a fast-paced, fact-filled setup, he defines the problem: “Nearly 100 million Americans are today either overweight or obese. That’s more than 60 percent of all U.S. adults.”

- He suggests a cause: When he was growing up, his mother cooked dinner every single day. Now, he says, families eat out all the time, and pay for it with their wallets and waistlines.

- He notes a cost: “Obesity is now second only to smoking as a major cause of preventable death in America.”

- About 2:00 in, Spurlock moves on to the lawsuit that inspired the film: “In 2002, a few Americans got fed up with being overweight, and did what we do best: They sued the bastards.” Using a magazine cover and animation, he lays out the basics of the case, which was filed on behalf of two teenaged girls: a 14-year-old, who was 4 feet 10 inches and weighed 170 pounds, and a 19-year-old, 5 feet 6 inches, who weighed 270 pounds. Sounding astounded, Spurlock says the “unthinkable” was happening: People were suing McDonald’s “for selling them food that most of us know isn’t good for you to begin with.”

- He then offers evidence to show that we eat it anyway, millions of us worldwide.

- Returning to the lawsuit, he highlights a statement by the judge, which he paraphrases: “If lawyers for the teens could show that McDonald’s intends for people to eat its food for every meal of every day, and that doing so would be unreasonably dangerous, they may be able to state a claim.”

- Spurlock seizes on this challenge but also notes a question, a theme that will inform the entire film: “Where does personal responsibility stop and corporate responsibility begin? Is fast food really that bad for you?”

At about 4:00, we see Spurlock for the first time on camera as he sets out the design of his experiment: “I mean, what would happen if I ate nothing but McDonald’s for 30 days straight? Would I suddenly be on the fast track to becoming an obese American? Would it be unreasonably dangerous? Let’s find out. I’m ready. Super size me.” With these words, the title sequence begins, with music. A minute later, as the music winds down, the film’s second sequence gets under way.

To summarize: The opening of Super Size Me has introduced the film’s train (eating only McDonald’s for 30 days), although Spurlock will lay out the specific rules as the film moves forward. It’s set a visual style that’s fast-paced, brightly colored, a combination of animation and live action, with Spurlock on camera as participant and voice-over as narrator. It’s set up the why of the film: an epidemic of obesity in the midst of a world increasingly filled with fast-food offerings. At the same time, it’s set up a thematic question about personal versus corporate responsibility. Is McDonald’s at fault for selling unhealthy food, or are people at fault for eating it? And it asks a basic consumer’s question: Is it really that bad for you, after all? The filmmaker has promised to take us on a journey and has made it clear that he doesn’t have all the answers: He wants to find out, and because of the skillful way he’s gotten this film going, the audience wants to find out, too.

Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple

The opening sequence of Stanley Nelson’s Jonestown lasts just under 2.5 minutes. The first frame we see is a fade up to a card, with white text appearing on a black background. All of the following appears on one card, but the phrases are added sequentially: On November 18, 1978/in Jonestown, Guyana,/909 members of Peoples Temple died in what has been called the largest mass suicide in modern history. The image fades, and the film dissolves to a small crowd, clustered together and smiling. A series of interviews are then intercut with archival footage. (The speakers are identified on screen later in the film, but not in the opening sequence, so I haven’t identified them here.)

- Woman: Nobody joins a cult. Nobody joins something they think is going to hurt them. You join a religious organization, you join a political movement, and you join with people that you really like.

- Man: I think in everything that I tell you about Jim Jones, there is going to be a paradox. Having this vision to change the world, but having this whole undercurrent of dysfunction that was underneath that vision.

- Jim Jones (archival): Some people see a great deal of God in my body. They see Christ in me, a hope of glory.

- Man 2: He said, “If you see me as your friend, I’ll be your friend. As you see me as your father, I’ll be your father.” He said, “If you see me as your God, I’ll be your God.”

- Woman 2: Jim Jones talked about going to the Promised Land and then, pretty soon, we were seeing film footage of Jonestown. [Jim Jones (archival): Rice, black-eyed peas, Kool-Aid.] We all wanted to go. I wanted to go.

- Woman 3: Peoples Temple truly had the potential to be something big and powerful and great, and yet for whatever reason, Jim took the other road.

- Woman 4: On the night of the 17th, it was still a vibrant community. I would never have imagined that 24 hours later, they would all be dead.

- Jim Jones (v/o archival, also subtitled): Die with a degree of dignity! Don’t lay down with tears and agony! It’s nothing to death. It’s just stepping over into another plane. Don’t, don’t be this way.” The film’s title comes up, and the opening sequence ends.

To summarize: This opening, like the others, sets out the promise, point of view, and style of the film to come. The opening title card is attention-grabbing, but it does something more: The film was released in 2007, which meant that for many viewers, the word “Jonestown” would immediately be a distraction as they tried to remember the details they knew about it. The text on screen helps to get that out of the way, putting a date to the event and reminding viewers of just how enormous it was. It also sets the event apart: it was the largest mass suicide in history; it’s an event to be understood.

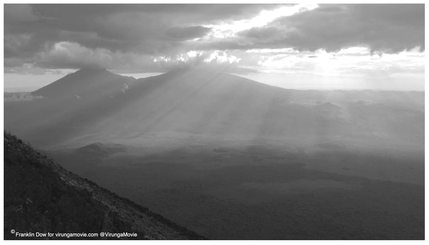

Virunga National Park, from Virunga. Photo © Franklin Dow, used by permission of the filmmakers.

In the first interview, a woman says, “Nobody joins a cult.” Other than the last speaker (an aide to Congressman Leo Ryan, who was in Guyana to rescue church members and was killed in the violence that ensued), all of the interviewees in the film’s opening sequence are former members; one is also a son of Jim Jones. Their words focus not on the mass suicide, but on the contradictions that Peoples Temple held for them, their belief in its promise and their regrets for what was lost. The opening is capped with archival audio from that last fateful day, but what lingers are questions in the audience’s mind about what happened and why.

Delivering on the Promise

Now you’re going to go through the entire film, slowly. The main things you’re looking out for are the elements discussed throughout this book:

- What is the central argument being made by the filmmaker(s)?

- What evidence do the filmmaker(s) offer in support of the argument? Does any of it seem more or less effective?

- How is this story told? Do you see a central narrative —a forward moving story, or train, that makes you want to keep watching? If so, what seems to be the goal or question that’s pulling you through the film, what is it you want to find out?

- Once you’ve identified the train, where and in what context does it return? Is it there at the film’s end? Does the film satisfactorily conclude the story it promised in the opening?

- Who are the people in the film, what role does each play in the overall story? Do some people seem more or less credible than others?

- What other elements stand out in this film? For example, does something stand out in terms of lighting, editing, music, cinematography, special effects, motifs, reenactments, etc.?

- Can you identify individual sequences (akin to chapters), that have a unique focus and a clear beginning, middle, and end?

- Do you see how the ordering of these sequences also advances the overall narrative?

- Does the film’s pacing feel slow to you? Does it feel dense with information? Just right?

Make some general notes, responding to the film in the way you’d respond to any movie. If it feels like it ends two or three times, note that. If it feels like it has two or three beginnings, note that. If a character feels superfluous, think about why. Do you find yourself engaged by the film, and if so, at what point(s) in particular, and why?

Identifying the Central Argument

This exercise is not unlike being asked to identify the central argument in a nonfiction article or book. This should be a sentence, rather than just a concept, and it’s helpful if it’s a bit specific. The central argument is akin to the theme; it’s the why of the film. (A film may have multiple themes and argue a few points, but there will likely be one central one.)

It’s possible that what you identify and articulate as the central argument may be different than what someone else sees; you just need to be able to offer specific reasons, from within the film, that you’ve made the choice you made. Even in the two examples below, my interpretation of the central argument may be different from that of the films’ directors.

Slavery by Another Name

This is a 90-minute film that I wrote, based on the Pulitzer Prizewinning book by Douglas A. Blackmon. Produced and directed by Sam Pollard, the film looks at various forms of forced labor (peonage, convict leasing, sharecropping) that were used in the U.S. South as a means of keeping newly freed blacks subjugated after the Civil War and the end of slavery. That’s the subject of the film. (The train was built around the presence, absence, inaction, and action of the federal government in response to this brutality.)

The film’s central argument is not sufficiently described as “racism” or even “racism is bad.” Better to be a bit more specific. The central argument might be articulated as: Legally sanctioned racial oppression and the coercion of black labor in the U.S. South in the decades after emancipation brutally curtailed black advancement while allowing white southerners to make unprecedented economic gains.

Taxi to the Dark Side

Here is an excerpt of the film description on Jigsaw Production’s website: “A documentary murder mystery that examines the death of an Afghan taxi driver at Bagram Air Base, the film exposes a worldwide policy of detention and interrogation that condones torture and the abrogation of human rights.” That’s what the film does.

But the central argument of the film, I think, moves beyond this statement. In film press materials, director Alex Gibney shares a lesson learned from his father,

that torture is like a virulent virus. . . that infects everything in its path. It haunts the psyche of the soldier who administers it; it corrupts the officials who look the other way; it discredits the information obtained from it; it weakens the evidence in a search for justice, and it strengthens a despotic strain that takes hold in men and women who run hot with a peculiar patriotic fever: believing that, because they are “pure of heart,” they are entitled to be above the law.

Building on this, one version of this film’s argument might be: A global policy that condones torture and the abrogation of human rights, as evidenced by events at Bagram and Abu Ghraib, gives lie to and threatens the values of freedom and individual rights that the policy is alleged to defend.

This isn’t an easy exercise. It’s worth trying to come up with the argument on your own, and then possibly comparing your argument with that of others who’ve seen the film, and then check out interviews or statements from the filmmakers, to see how your analysis lines up with theirs.

Identifying Sequences

In some ways, sequences are one of the most challenging aspects of documentary storytelling. The single best way to understand them is to try to identify them over the course of an entire film (or even better, several films). As discussed in Chapter 2, it might be useful to give the sequences you find a name that encompasses the unique job they do, as discrete chapters in the overall film. (Again, this is interpretive work; my description of what a sequence achieves may be different from someone else’s.) Also, it’s likely that the sequences will be easier to see and the breaks between them more clear-cut earlier in the film; once a story’s well under way, sequences may be interwoven as part of an overall speed-up in the film’s pacing.

As you look at sequences, consider also how the filmmaker transitions between them, whether it’s through a transitional line of narration, a music or sound sting, a fade into and out of black, or something else.

Examples of Sequences

Immediately after the opening sequence of Virunga, there is a sequence that we might think of as “Meeting Rodrigue Katembo.” The sequence follows him and others on what lower thirds describe as “routine ranger patrol, Virunga National Park, present day.” They encounter gunfire, discover an illegal settlement, arrest a poacher, and set fire to the hut the poacher’s been using. After a brief interlude—a shot of a gorilla, a shot of two hippos, a beautiful view of the park at dusk—the filmmakers talk with Katembo as he works on his rifle. (Watch how they intercut the footage of him with the archival imagery of child soldiers, giving us a sense that he is pointing a gun at what he is seeing, and later, as he talks about his older brother, that he is haunted by what he is seeing.) In sync and in voice-over, Katembo tells us about being recruited as a child solder; about his brother’s death; about his mother’s insistence that he escape to save his life. “So then I escaped the army to dedicate my life to the National Park,” he says. The sequence ends about eight minutes into the film; there is transitional nature footage, and then the next sequence begins, one that we might think of as “Meeting Andre Bauma and the orphaned gorillas.” And so on. In this one sequence, we’ve learned a bit more of the history, but we’ve also come to understand the backstory of a central character and to see what motivates him as he takes risks on behalf of this park.

The first sequence of Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple is the opening described above. Sequence 2 is very brief (2:20–3:10), and it’s just a story about Jim Jones which reveals, as the speaker says, “everything was plausible, except in retrospect, the whole thing seems absolutely bizarre.” The sequence is thematic; it establishes the idea that definitions of “normal” may be fluid. The next sequence (3:10–7:08) presents the Peoples Temple in its heyday; it is a church full of song and success, offering insight into the positive community that members initially joined. From there, the music takes a somber turn, and the film moves back in time. Sequence four (7:08–13:28) is titled onscreen “Indiana, 1931–1965.” The sequence moves Jim Jones from childhood to adulthood, revealing frightening character traits; it shows his discovery of the kind of religious workshop he comes to emulate; it launches a pattern of isolation, as we see his church moving to rural California to escape Indiana’s opposition to integrated membership, and as we see Jones beginning to pull family members away from families. The next sequence begins, with the title “Ukiah, 1965–1974.”

As noted, it’s useful to chart sequences throughout an entire film, giving them names if possible. Keep track of how long each sequence is, and how “complete” it feels—if there is some sort of beginning, middle, and end to it. What do you learn in the sequence that you didn’t previously know? What job does the sequence do? How does it change or advance your understanding of the film’s overall narrative— the sequences that came before, and those to follow?

Compare and Contrast

Another exercise that’s useful is a “compare and contrast” between two or more films on the same general subject. This exercise is about really seeing how these films are constructed, as opposed to just deciding if you prefer one to the other. Does one version talk at you and the other engage you, and if so, why? Does one leave the audience with more parts of the puzzle to solve, and is that process satisfying? Does one feel more or less honest or manipulative, and if so, why? In thinking about the answers, consider also the experience of the filmmakers, the purpose for which the film was made, and the audience the film eventually reached.

Write a Close Analysis of One Aspect of the Film

The MFA program I attended at Goddard College required us to write annotations of numerous creative works. These were short (just two to three pages, double-spaced) papers in which we were to make and support a focused argument about a specific element in whatever we were studying, such as a play or a novel. I found this exercise very useful, and now assign something similar to students of documentary. They provide a disciplined way to closely watch movies, and can be especially useful when it comes to documentary, where the temptation is often to respond to a film’s subject matter. (After viewing Blackfish, for examples, students may want to write about SeaWorld or its trainers. But a film analysis requires that they respond to something about the craft; how the filmmakers presented this content.)

A good film analysis asks the viewer to consider one aspect of the craft, studying the film closely in order to make and support an argument about that one aspect, with evidence. You might want to figure out how a filmmaker did something that you found particularly effective, or you might want to figure out why something confused or annoyed you. You might look at a particular idea or thread that runs through a film, teasing it apart to see where and how it appears and with what overall effect.

You want to avoid writing a plot synopsis, film review (avoid adjectives and judgment), opinion piece, or film “report” (like a book report), that merely observes. For example, a report on Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line might include observations such as: “Here, the film intercuts between the two main subjects before moving on to show a reenactment of the officer being shot. After this, the film brings viewers through the journey to discover which of the two subjects did the shooting. . . . Errol Morris presents evidence including court papers, photographs, and newspapers stories. Interviewees including police officers describe the events and the suspects.” That’s not analysis.

Similarly, a review tends to use adjectives (powerful, blistering, boring, heartbreaking) or make judgments. The trick is to turn the judgment into a question. For example, a review might state, “One minor blunder in the film, which detracts from its value, was that individuals interviewed by Morris (The Thin Blue Line) were not identified on screen.” An analysis might ask, “What was gained by the filmmaker’s decision not to identify on screen the individuals being interviewed?” Or, “Morris chose not to offer on-screen identification of his characters. By what other means do we know who these people are, in terms of their identities and connection to the story?”

It’s important that these analyses adhere to a single focus. Rather than spend a paragraph looking closely at the role of reenactments, and then a paragraph looking at the use of title cards, and then a paragraph about the filmmaker’s choice not to identify talking heads, it’s much more valuable to take one thread or idea and look closely at it as it’s demonstrated in a range of craft choices.

Watching For Act Structure

As will be clear from some of the interview chapters, many excellent filmmakers don’t consciously think about three-act structure when they make films. That doesn’t mean that you can’t utilize dramatic structure as one tool for looking closely at a completed film. You may do the math, look for structure, and discover that you can’t find it. Or you may find some unexpected organization behind the film that’s easily overlooked when the story is complex and interwoven. The bottom line is that you’re doing this to see the film more clearly. You’re looking for a pattern, for ideas, for insight.

So: Make note of how long the film is. To roughly see if you can find act breaks, generally divide the overall film by four. The first act is roughly a quarter of the way in, which means you look at what’s happening in terms of the train at around that point, and if you can see a definitive end to one act that might push us into the second act. You do the same at the midpoint of the film (which is also the midpoint of Act Two), and then again about three-fourths of the way through the film, as Act Two gives way to Act Three. The train should reach a climax very close to the film’s end, and then there is generally a short resolution. Remember: The act breaks relate to the film’s central spine, its narrative train.

What follows is a breakdown of Super Size Me, noting both act structure and the train. You’ll notice that once the train is under way, surprisingly little actual screen time is spent eating at McDonald’s. Instead, the train breaks up the rhythm of the overall film and makes it possible for the filmmaker to focus on a range of issues, from childhood obesity to the fast-food industry, resulting in a film that has been used in classrooms around the world.

Super Size Me

From first frame of action to closing credits, the film is about 96 minutes long. That means that I would expect the first act to end roughly around 24 minutes; the film’s midpoint (halfway through Act Two) is around 48 minutes; and the third act should begin around 72 minutes.

Act One

The first act begins with the opening sequence, described earlier. After the opening titles, Spurlock spends time establishing a baseline for his own physical condition. Three doctors, a nutritionist, and a physiologist confirm that his health is excellent. They aren’t thrilled by the experiment, but don’t expect anything too terrible to happen in just 30 days. Roughly 10.5 minutes into the show, Spurlock adds a further wrinkle: Because more than 60 percent of Americans get no form of exercise, neither will he, other than routine walking. (This prompts a sidetrack about walking in general, walking in Manhattan, and how many McDonald’s there are to walk by in Manhattan.)

At 12:03, we’re back to the train as we meet Spurlock’s girlfriend Alex, a vegan chef. She prepares “The Last Supper,” one of a handful of chapters named on screen over original artwork. A little over a minute later, the experiment gets under way, as “Day 1” is identified with text on screen. Spurlock orders an Egg McMuffin and eats. (Here, as in several places throughout the film, he breaks up blocks of narration with musical interludes. These breaks are important; they add humor and breathing room, giving the audience a chance to process information.) In a quick scene, we see Spurlock writing down what he’s eaten. We need to see this record-keeping at least once, because it’s part of the experiment: The log provides the data the nutritionist uses to calculate his food intake. We then see Spurlock on the street, asking people about fast food. Interspersed at various points throughout the film, these interviews also add humor and alter the rhythm of the film, while providing a range of what are presumably “typical” responses.

Around 15 minutes into the film, standing in line at McDonald’s, Spurlock expands on the experiment’s rules (he talks on camera to his film crew, and also in scripted voice-over). After getting this additional exposition out of the way, he bites happily into a Big Mac (gray area—he enjoys some fast food). At 15:47, another piece of artwork, another title: “Sue the Bastards.” We see Spurlock again on the street conducting interviews, this time about the lawsuit. All three of the people consulted think the lawsuit is ridiculous—which at this point in the film may also be the attitude of the audience. Spurlock interviews John F. Banzhaf, a law professor “spearheading the attacks against the food industry” and advising the suit’s lawyers. Spurlock gives Banzhaf’s work a bit of credibility (to counter the man-on-the-street responses) by noting that people thought Banzhaf was crazy when he was going after tobacco companies, too—“until he won.” Banzhaf adds an important detail about why McDonald’s is a particular target: The company markets to children.

Another man worried about the children, Spurlock says, is Samuel Hirsch, lawyer for the two girls in the lawsuit. But look at the gray area in this interview. Over a shot of Hirsch, we hear Spurlock ask, “Why are you suing the fast-food establishment?” The shot continues, unedited, as Hirsch considers, smiling. “You mean motives besides monetary re—, compensation? You mean you want to hear a noble cause? Is that it?” The lawyer seems to consider a bit longer, and then Spurlock cuts away from him, and that’s the end of Hirsch’s time on screen. It’s funny, but perhaps more importantly, this willingness to paint various sides of the argument in less-than-flattering light is part of what makes this film engaging. Audiences have to stay on their toes and be willing not only to see complexity, but figure out for themselves what they think.

David Satcher, former U.S. Surgeon General, introduces the problem of “super sizing,” which allows Spurlock (and other experts) to explore the issue of portion size. In other words, Spurlock is building an argument and letting one idea flow to the next. Finally, it’s just under 21 minutes into the film and we’ve been away from the “train” for about five minutes, so Spurlock drives up to a McDonald’s, and text on screen announces “Day 2.”

Act Two

In the second act, the experiment really gets under way. Fortunately for Spurlock, he was asked on Day 2 if he wanted to super size, and by the rules he’s established, he must say yes. (There might be a temptation, in a film like this, to let Day 4 stand in for Day 2, if it provided an opportunity like this. You can’t. You don’t need to give each day equal weight——some days are barely mentioned—and you don’t need to show all meals each day. But the timeline of these meals needs to be factual, as does the timeline of Spurlock’s health.) Watch how Spurlock condenses time in this scene: He starts out laughing, kissing his double quarter-pounder, calling it “a little bit of heaven.” The image fades to black, and white lettering comes up: “5 minutes later.” Fade up: He’s still eating. (The visual point, underscored by the card and by the screen time given to the scene, is that this is a lot of food, and for Spurlock, it’s an effort to eat it.) Fade to black again: “10 minutes later.” Spurlock says that a “Mcstomach ache” is kicking in. To black, then: “15 minutes later.” He’s leaning back in his seat. To black, then: “22 minutes later.” He’s still forcing the food down. A cut, and we see him leaning out the window and vomiting. A meal that lasted at least 45 minutes has been effectively compressed into a sequence that’s 2.5 minutes long.

At about 23:18, we see a new illustrated chapter title, “The Toxic Environment.” Experts and Spurlock introduce the problem of “constant access to cheap, fat-laden foods” and soda vending machines, compounded by a reliance on cars. After a brief health concern on Day 3, he cuts to Day 4 and takes a detour to further compare obesity and tobacco use, including marketing to children. This sequence is followed by another “meadow” (or musical interlude), in which we see Spurlock enjoying a McDonald’s play area.

At 28:21, a new chapter, “The Impact,” explores the lifelong health implications, including liver failure, of obesity in children. At 30:38, Spurlock cuts to a 16-year-old, Caitlin, cooking in a fast-food restaurant. Here again, his ambivalence seems to leave some of the work to the audience. In an interview, Caitlin talks about how hard it is for overweight teenagers like herself because they see the pictures of the “thin, pretty, popular girls” and think “aren’t I supposed to look like that?” As she’s talking, Spurlock fills the screen with images of thin young women, until he’s covered Caitlin’s face. Just before she disappears, she concludes: “It’s not realistic, it’s not a realistic way to live.”

Is Spurlock implying that Caitlin is letting herself off the hook too easily? This may be the case, because the scene is immediately followed (32:07) by a sequence in which motivational speaker Jared Fogle, who lost 245 pounds on a Subway diet, gives a talk at what appears to be a school. An overweight eighth grader argues, like Caitlin, that weight loss isn’t realistic: “I can’t afford to like, go there [to Subway] every single day and buy a sandwich like two times a day, and that’s what he’s talking about.”

As if to offer a contrast, the film then cuts to a sequence about a man who did take personal responsibility for his health: Baskin-Robbins heir John Robbins. According to headlines on screen, he walked away from a fortune because ice cream is so unhealthy.

Robbins, a health advocate, runs through a litany of health-related problems involving not only his own family but also one of the founders of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream. (This sequence, like the many shots in the film of fast-food companies other than McDonald’s, helps expand the argument beyond one company to look at larger issues of food choice and health.)

At 35:09, it’s Day 5 of the experiment. We see Spurlock ordering food but don’t see the meal; instead, we follow Spurlock into his nutritionist’s office, where we learn that he’s eating about 5,000 calories a day, twice what his body requires, and has already gained nine pounds. Hitting the streets again (about 37:00), he asks a range of people about fast food (they like it) and exercise (only some do it).

About a minute later, Day 6 finds him in Los Angeles, ordering chicken McNuggets. This meal motivates another look at the lawsuit and McDonald’s statements about processed foods; Spurlock augments this with a cartoon about the creation of McNuggets, which he says the judge in the case called “a McFrankenstein creation.”

Back to the experiment, Day 7, and Spurlock isn’t feeling well. Within 30 seconds, it’s Day 8, and he’s disgusted by the fish sandwich he’s unwrapping. Less than 30 seconds later, it’s Day 9, and he’s eating a double quarter-pounder with cheese and feeling “really depressed.” He’s begun to notice not only physical but also emotional changes. The following sequence, with an extreme “Big Mac” enthusiast, doesn’t add to the argument but is quirky and entertaining.

With that, we return (at 43:00) to an idea raised earlier, the notion of advertising to children. An expert offers data on the amount of advertising aimed at kids, and how ineffective parental messages are when countered with this. Another expert points out that most children know the word “McDonald’s,” so Spurlock—in a scene set up for the purposes of the film—tests this out, asking a group of first graders to identify pictures of George Washington, Jesus Christ, Wendy (from the restaurant), and Ronald McDonald. He also uses a cartoon to demonstrate how much money the biggest companies spend on direct media advertising worldwide.

At 46:34, we’re back to the experiment: “Day 10.” But once again, we leave the experiment quickly. By 47:02, a new illustrated chapter title appears, “Nutrition.” This sequence doesn’t actually look at nutrition, but at how difficult it is to get nutrition information in stores. As John Banzhaf argues, how can people exercise personal responsibility if they don’t have the information on which to base it? At 49:20 (roughly midway through the film), we’re back to the experiment, as Spurlock gets his first blood test. He now weighs 203 pounds, 17 more than when he started.

Around 50:30, a new chapter: “It’s for kids.” Spurlock takes the essay even wider, with narration: “The one place where the impact of our fast-food world has become more and more evident is in our nation’s schools.” This is a long sequence in which he visits three schools in three different states. In Illinois, the lunch staff and a representative for Sodexo School Services (a private company that services school districts nationwide) seem willing to believe that students make smart food choices, even though Spurlock shows evidence that they don’t. In West Virginia, Spurlock visits a school served by the U.S. federal school lunch program. Here, students eat reheated, reconstituted packaged foods, with a single meal sometimes exceeding 1,000 calories. Finally, Spurlock goes to a school in Wisconsin, where a company called Natural Ovens provides food for students with “truancy and behavioral problems.” The food here is not fried or canned, and the school has no candy or soda machines. (It’s almost a shock at this point to see fresh vegetables and fruit and realize how brightly colored they are.) The behavioral improvements in the students here, administrators tell us, are significant. And, Spurlock notes, the program “costs about the same as any other school lunch program. So my question is, why isn’t everyone doing this?” (56:02).

Over footage of the Wisconsin lunch line, we hear a phone interview in which the founder of the Natural Ovens Bakery is allowed to answer Spurlock’s question: “There’s an awful lot of resistance from the junk-food companies that make huge profits off of schools at the present time,” he says. To me, this is a misstep in an otherwise powerful sequence. Unlike several of the experts who’ve been interviewed, this man’s ability to speak for or about “the junk-food companies” hasn’t been established. (I’m not saying it doesn’t exist, just that it’s not set here.) The information he conveys may be fact checked and 100 percent accurate, but to me, a better way to convey it might be through facts, such as how much money per year the fast-food companies actually make in the nation’s public schools. (That companies resist being removed from schools is a point made, effectively, in the following scene, when the Honorable Marlene Canter talks about the Los Angeles Unified School District’s ban on soda machines.)

At about 57:08—roughly 60 percent of the way through the film— Spurlock returns to the experiment. It’s Day 13, and he’s in Texas, home to five of the top 15 “fattest” cities in America. Day 14 finds him in the #1 city, Houston, but he quickly goes into a new sidetrack: a visit with the Grocery Manufacturers of America, a lobbying firm based in Washington, D.C. The group’s vice president says the issue is education, teaching good nutrition, and teaching physical education. It’s a bit of a thin transition, but this leads Spurlock to explore the fact that only one state, Illinois, requires physical education for grades K–12. Returning to the Illinois school, he films an exceptional program, and then for contrast, shows an elementary school in Massachusetts where physical education involves running around a gym once a week for 45 minutes. At 61:00, Spurlock suggests a reason for the issue, the “No Child Left Behind” education reforms of President George W. Bush, which an expert says explains cuts to “phys ed, nutrition, health.” This, in turn, motivates Spurlock to ask students in a ninth-grade health class what a calorie is. They struggle to answer—but so do six out of six adults interviewed on the street.

At 63:02, it’s Day 16, “still in Texas,” but in about 20 seconds, it’s Day 17 and he’s back in New York. We learn that the experiment is getting to Spurlock; his girlfriend says he’s exhausted and their sex life is suffering. The following day, the doctor says his blood pressure and cholesterol are up and his liver “is sick.” He’s advised to stop. We see him talking on the phone to his mother; they’re both concerned. She’s afraid the damage he’s doing will be irreversible, but Spurlock reassures her that “they” think things should get back on track once it’s done. Act Two ends here.

Act Three

At 69:26, Act Three (and again, as with the other films, this is my analysis, not the filmmaker’s) begins with a look at the “drug effect” of food, with input from a new expert, a cartoon about McDonald’s use of the terms “heavy user” and “super heavy user,” and an informal phone survey. Spurlock learns that his nutritionist’s company is closing, and uses this as an opportunity to explore the amount spent on diet products and weight-loss programs compared with the amount spent on health and fitness. This motivates a transition to an extreme weight-loss option, gastric bypass surgery, filmed in Houston (74:03). Note that this sequence may have been filmed anywhere during this production; its placement here in the film makes sense, because things are reaching their extremes.

The stakes for Spurlock have also continued to rise, which helps to make this third act strong. At 77:33, in New York, Spurlock wakes at 2:00 a.m.; he’s having heart palpitations and difficulty breathing. “I want to finish,” he says, “but don’t want anything real bad to happen, either.” More visits to doctors result not only in specific warnings about what symptoms should send him immediately to an emergency room, but also the realization that these results are well beyond anything the doctors anticipated. But at 81:20, Spurlock is back at it: Day 22. In short order, he sets out to answer a new question that he’s posed: “How much influence on government legislators does the food industry have?” He visits again with the Grocery Manufacturers of America, before finally (at 83:26) attempting to contact McDonald’s directly.

These efforts, ultimately unsuccessful, will punctuate the rest of the film. Spurlock gets through Days 25, 26, and 27 quickly. At Day 29, he’s having a hard time getting up stairs. By Day 30, his girlfriend has a detox diet all planned out. First, there’s “The Last McSupper”—a party at McDonald’s with many of the people we’ve seen throughout the film. Then it’s off to a final medical weigh-in. Fifteen calls later, still no response from McDonald’s.

Resolution

At 89:34, Spurlock is nearing the end of his film, and essay. He returns again to the court case. “After six months of deliberation, Judge Robert Sweet dismissed the lawsuit against McDonald’s,” he says. “The big reason—the two girls failed to show that eating McDonald’s food was what caused their injuries.” Spurlock counters by tallying up the injuries he’s suffered in just 30 days. He challenges the fast-food companies: “Why not do away with your super-size options?” But he also challenges the audience to change, warning: “Over time you may find yourself getting as sick as I did. And you may wind up here [we see an emergency room] or here [a cemetery]. I guess the big question is, who do you want to see go first—you or them?”

Epilogue

Before the credits, the filmmakers do a quick wrap-up, including information about how long it took Spurlock to get back to his original weight and regain his health, and the fact that six weeks after the film screened at Sundance, McDonald’s eliminated its super-size option. At 96:23, the credits roll.

SOURCES AND NOTES

There are several resources for close reading, including Francine Prose’s Reading Like a Writer (New York: Harper Perennial, 2007). Information about Goddard College’s MFAW program is available at www.goddard.edu/academics/master-fine-arts-creative-writing-2/program-overview/. Information about documentary box office can be found at www.documentaryfilms.net/index.php/documentary-box-office/.