Chapter 19

Stanley Nelson

Filmmaker Stanley Nelson has been awarded five prime-time Emmy Awards, two Peabody Awards, a 2002 Fellowship (often called the “genius” award) from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and a National Medal in the Humanities, bestowed in 2013 by President Barack Obama. Eight of his films have premiered at the Sundance Film Festival: The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution (2015); Freedom Summer (2014); Freedom Riders (2011); Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple (2007); A Place of Our Own (2004); The Murder of Emmett Till (Special Jury Award, 2003); Marcus Garvey: Look for Me in the Whirlwind (2000); and The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords (Freedom of Expression Award, 1999).

In 2000, Nelson and his wife, Marcia Smith, an award-winning writer and philanthropy executive, founded the independent production company Firelight Media. In 2008, they expanded the company’s mission, creating the Firelight Producers’ Lab, a mentorship program for emerging diverse filmmakers. In 2015, the Lab was one of nine nonprofit organizations worldwide to receive the MacArthur Foundation’s Award for Creative and Effective Institutions, a one-time grant of $500,000 to help ensure the Lab’s sustainability.

When we spoke in February 2015, The Black Panthers had just premiered at Sundance and Nelson was moving forward with two new films—The Slave Trade: Creating a New World and Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Historically Black College and Universities—that are part of America Revisited, a trilogy that includes The Black Panthers.

How you think about story as you approach your films?

Every film is different. I’m always looking for a beginning, middle, and end to stories. What’s the throughline? What’s the story about, aside from the obvious A to B to C? I’m looking at all those different pieces.

When making films about topics that are likely to be somewhat familiar to audiences, like the American civil rights movement, what is your process for finding new information or new insights?

Many times, the stories that I’ve worked on, for one reason or another, have not been fully told, or are not known to the general public. So a lot of times, just in the telling, it’s a fresh story. But when I look at the films I’ve done as a whole, I tend to try to find the people behind the scenes who were part of the story, who aren’t the famous people necessarily, and then to try to tell the story from as many different angles as I possibly can.

So in Freedom Riders [the story of a campaign, May to November 1961, in which black and white Americans rode together on buses throughout the U.S. South to protest racial discrimination], we interviewed the Freedom Riders, we’re interviewing the governor of Alabama, we’re trying to interview people that had the federal government’s point of view, and also people who can talk about the local people, to try to get as many different sides of the story as we can. Why would somebody burn a bus just because people are trying to sit together on that bus? By and large, people make decisions that are at least rational to them at that time. So what rationality would make somebody burn a bus, or attack people with lead pipes, just because they’re sitting together?

And then just visually, we’re trying to tell the story in a different way. People have seen footage of the civil rights movement before. So we’re trying to find new pictures and footage to tell the story in a different and new way.

How do you explain to students or new filmmakers why it’s important to seek out alternate points of view?

I think it only makes the story stronger if you show that there are other opinions. We can see through those opinions today. It doesn’t make it any more sensible, that they attacked these riders on the buses. It just illustrates, in a lot of ways, how wrong they were.

As I’m talking, I’m thinking about something like the Black Panther film, where you hear from the cops. They seem very rational, and it makes sense. I think it really helps the film, because you see it as a viewer, and part of you is saying, “What about the other side?” Even if you’re not consciously thinking that, I think unconsciously you are. And so by giving the other people a say, you head that off a bit.

It also seems to help if you’re not only telling a story but also building an argument and presenting evidence. By presenting multiple viewpoints, you’re letting the evidence speak for itself.

Yes. I think that’s partially what we try to do, is to build a case, build an argument, tell a story. And of course in practice that’s not as easy as it looks—good structure tends to feel inevitable, which is one of the reasons I ask students to closely watch multiple films on the same story.

Your hour-long film The Murder of Emmett Till, for example, has a very clear structure. [Till, a black teenager from Chicago, was murdered in 1955 by two white men in Money, Mississippi. They were acquitted by an all-white jury, but later admitted their crime to a reporter for Look magazine.] The film’s opening minutes include a newsreel story about the murder. Can you talk about deciding to launch the film that way?

The newsreel was great because it gives the whole story, but it didn’t really work to use it [later], to describe the actual kidnapping and murder, because it didn’t have the drama we wanted. And so we had cut it from the film. But then I thought of just using it—I call it the Citizen Kane moment—where we can have him tell the whole story, and then go back and retell the story in detail. That’s why the film starts as it does.

Structurally, the opening minutes are also critical to the film because you go beyond teasing the murder. Through quick interview excerpts, you set out the bigger themes and the “why” of the overall story: This was a final straw that helped to ignite real change.

We always felt that the story was in some ways about the clash of cultures between Mississippi and Chicago. If he hadn’t been from Chicago, his mother would have never left the coffin open. His mother would have never been able to marshal newspaper and magazine coverage of his murder. It would have just passed, one of those murders down south that are not even covered in the news. And also that he didn’t understand the culture of Mississippi; that he whistled to this white woman and thought it was kind of a joke. He didn’t really understand it. And there was this unwritten agreement between the North and the South, that the South would do what it wanted and the North would ignore it. That was at the heart of the whole Emmett Till case: Mamie Till made it so that the North couldn’t ignore the South.

From there, the forward moving story of the film gets under way, and you start with two distinct sequences. The first establishes the racial climate of rural Mississippi at the time. The second introduces Till and the very different world he’s from, urban Chicago. The result is that when he heads south to visit relatives, we know enough to be afraid for his safety, but he doesn’t. And we suspend our disbelief—we’re in that moment with him, hoping for the best. I think that that is really important, that you bring the audience on a journey with you in the film. One of the clearest examples is in Emmett Till, where we talk about Chicago, and the woman says, “We used to dance to rock ’n’ roll. The girls wore these pleated skirts. The boys wore these rubber shoes.” And then near the end of the film, as the murderers describe what they’ve done to Look magazine, they say, “We burned his clothes to the shoes, but the shoes wouldn’t burn because they were rubber.” And we don’t say anything more about it, but hopefully, as a viewer, you make the connection, so that there’s a moment of discovery. And so that it puts you into the story a little bit.

How do you decide what material to reenact?

In general, I’ve tried to keep the reenactments down to a minimum. One, that’s just my feeling; but two, I think it’s very hard to do reenactments. They’ve got to be perfect. They can’t seem like, “Oh, those are actors,” or “Where’d they lift that bus from?” It has to be organic in the film, so we try to keep it down. But sometimes there are just no visuals. In Emmett Till, there was nothing of the night he was kidnapped. In Freedom Riders, we really wanted you to [feel like you were] on that bus or on that journey, so we shot a lot of buses, and wheels on the road, to help put you there.

Part of good storytelling is making choices about what to include or not include. How do you make those choices while remaining truthful to your subject?

I think the first thing is that you have to draw limits on when the story begins and ends. Sometimes it happens on paper before we start. Sometimes it happens in the edit room, and those are sometimes the hardest decisions to make.

In Freedom Riders, we wanted to do a long piece about nonviolence and the legacy of nonviolence as it comes down from Gandhi and goes into the movement. When we did interviews, we talked to people about how they were influenced by Gandhi and the Indian struggle. Gandhi had said that the true test of nonviolent civil disobedience would be in the United States, because African Americans were the minority [rather than the majority, as in India]. So how do you change things if you’re a minority? But as we got into the film—and so many times this happens—as we got into the editing, a lot of the background stuff had to fall by the wayside because we’ve got to get into the story. You don’t want to start the story in India in 1947 or something. And it’s hard, once you get into the story, to get back and talk about those things. It’s much easier to do in a book. You can always write another chapter in a book.

So a lot of times, the first thing you have to do is say, “Okay, what are the parameters of the story?” And look, in some ways we’re making those up. The Black Panthers could have gone on to 1982 or so, when the Panthers actually disintegrate. They spent a long time disintegrating, so we could have gone on. We had thought about starting the film out with a guy named Robert Williams, an African American who advocated defending yourself with guns. Or we had a whole piece on the Watts riots, or Watts rebellion. Then once we got into cutting, we just couldn’t do it. So one of the first decisions is: Where does the story begin and where does it end? That’s really central to how these stories are told.

And then within the film, there are different sequences, obviously. We want a sequence, as much as possible, to lead to something else.

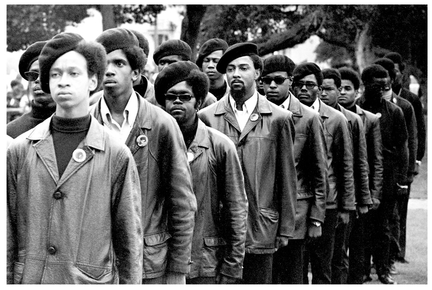

Panthers on parade at Free Huey rally in Defermery Park. Photo: Stephen Shames, used by permission of the filmmakers.

So you might choose between possible sequences on that basis.

An example of that is, in the Freedom Rides, they stopped somewhere in the northern part of the South, and they got [attacked], but then they get back on the bus and kept going. And finally we said, “This story doesn’t lead anywhere.” You know what I mean? There are other attacks that happen later that are much more important. You don’t want to have this series of attacks to where it wears you down.

I describe sequences as chapters. They’re unique in themselves, and then they advance the overall story.

Right. That’s what they do. You really want them to advance the story, or else it’s just kind of there. And I think as an audience you might not, in your mind, connect and say, “Wow, that was a nice story but it didn’t really go anywhere,” but part of you does feel that. You really want each sequence to push the whole forward.

In the Black Panther film, we look at the LA shootout [an early-morning police raid on Panther headquarters in Los Angeles, December 8, 1969]. There are a lot of different shootouts, but we picked the LA shootout to use because there’s a lot of video—it lasted for five hours, and the press had a chance to get there, and for whatever reason, the police let them get close enough to film it—and it’s a very important shootout. But we could have done others.

A clearer example is in Jonestown. Everybody had a story of some crazy sexual thing on Jim Jones. Just everybody. But we couldn’t have ten stories of Jim Jones’ craziness, and so we had to pick a couple of stories to illustrate that. You try to pick stories that stick in your mind, that illustrate it best. And who knows why that is, why some stories resonate and some don’t? And sometimes it’s a matter of visuals, that you have visuals to back it up.

Let’s talk a bit about Jonestown. [In November 1978, more than 900 member of the California-based Peoples Temple, founded and led by the Reverend Jim Jones, died in a mass murder/suicide in Guyana.] Some films about this event present Temple members as an undifferentiated group of crazy cultists. Your film brings the audience along with Temple members as they spiral downward, toward Guyana, and the line of “normal” keeps changing. Was that a goal, to put the members back into the historical narrative, as people?

Yes. The way we came to the Jonestown story is that my wife and I heard some former members of Peoples Temple on the radio. It was some kind of anniversary of the Jonestown murders, and we heard them talking about it, and they sounded so sane. They talked about how they joined this progressive church that did all of this great work, and it was about loving each other, and it was such a great thing, and it all turned bad. And it started us thinking about it in a different way. The way the story’s always told is that these 900-and-something crazy people commit suicide. But how do you get 900 crazy people? You couldn’t gather 900 crazy people if you tried. So these people were in some ways rational, up to a point. And so we really wanted to take you on this journey. How did a rational person join this thing and stick with it for years? What was that all about?

Do you consciously use three-act dramatic structure?

No. I do not. I do have to say that. I know what it is, and maybe it’s in the back of my head in some ways, but no, I don’t.

My theory is that it’s hard-wired. If you do an analysis with three-act structure of Jonestown, for example, the acts seem to shift on the theme of suicide. It’s really interesting.

Yes, I think that three-act structure is ingrained in us. I look at it as beginning, middle, and end. Any story has to have these pieces to it. So that’s what I’m looking at. I’m looking to try to tell this story. But I’m not consciously thinking of what’s the first act, what’s the second act, what’s the third act, in that way. Look, you have to begin. You have to have a beginning. Then something has to rise up in the middle. Something has to change. Something has to happen in the middle, and then there’s got to be some kind of resolution to it. So I think it’s natural, but it’s not something that I think about as I’m going forward.

What is your process? Do you write an outline or treatments before you film?

It really depends on the project and who the project is for, in some ways. American Experience [a PBS series that’s presented seven of Nelson’s films] wanted a written treatment and then a written script. So I think that that has really helped me, because at first it seemed like “Why are we writing this thing out?” But I think as a discipline, it really helps to have a script, even though you kind of throw it away as you go. We tend to have a first treatment, then kind of a written script that guides me in terms of interviews and interview subjects, and in some ways puts some limitations on how many interviews we do and what we’re asking and where we’re going. It’s kind of a roadmap. One way to look at it is like if you’re going on a summer trip and you say, “I’m going to drive from New York to California,” you have to have a map so you don’t end up in Canada somewhere.

How do you work in the editing room?

In the edit room what we do, nuts and bolts, is we take the interviews and lay out an assembly, which is basically to lay out the story of the film from beginning to end, with all the bites that we’ve got that we like. So I think one of the keys for me in the editing process is, I’m constantly cutting the film down. And I think what saves me is that once I cut something, I’m really pretty sure that that’s out. So it’s a constant whittling down. And we lay the film out in terms of all the bites that we like, in a very, very, very rough form, based on the script from beginning to end. And the first time through, we’re not making hard choices. We might have three people talk about the same exact thing, but we’re not making a choice of which one we use.

We’re trying to keep in any kind of humor, anything anybody says that is in any way humorous, because so many times these subjects are so serious. Or we just like it. So for whatever reason, “I just like this.” Because again, I’m trying not to go back, which is central. I’m trying not to go back and say, “Oh, what about when he said this? I really liked that.” You know what I mean? So everything is kind of in. And then we just keep cutting down, cutting down, cutting down.

The thing that we’ve done recently, because so many of the films that we’ve done in the last couple years have not had narration, is we’ll save maybe a third or fourth of the interviews to do after we’ve gotten some kind of cut to look at. And a lot of time they’re central interviews. So we didn’t interview Ray Arsenault, who wrote the book Freedom Riders, who was central to the film, until very late in the process, because he could fill in holes. I could talk about anything because he had written the book.

I try my best to save historians ’til later, because I’m trying as much as I can not to interview historians. You don’t want the story of the Freedom Riders or the Panthers to seem like it’s being told by historians; usually you [just] need a couple. Jonestown is probably the film that needed the least historians, because so many of the people in Jonestown had already written books, and they served as their own kind of historians. But we’re trying to hold back and do the interviews with the historians last.

So for the rest of the casting . . .?

We talk to a lot of people on the phone. A lot of times there’ll be a co-producer and they’ll do pre-interviews, and write up what was said and what they liked. And one thing that we’ll always do is, if somebody says something that we really like, word for word, we’ll write that down and put it in quotes, so that we can try to get it out of them again. In Emmett Till, Wheeler Parker—who’s Till’s cousin—describes the night they took Emmett Till: “It was as dark as a thousand midnights; you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face.” When he said that in the pre-interview, I put that in quotes; I want to try to get that.

So you’re not coaching them, but you’re asking questions in a way to elicit that?

Right. We’re trying our best to get them to repeat what they said. And it may get down to reminding them that they said it. I don’t feel bad about that, because it’s their words. It’s not like I’m saying, “Say this.” It’s like, “You said this before.”

Given a choice, you would prefer not to use narration?

Look, I love great narration. I think that narration is great. But given a choice, yes, because I think people connect in a slightly different way to a film with no narration. It does make the degree of difficulty that much more, to try not to have narration. There are things that you just can’t say, because the people never said it or they never said it clear enough or quickly enough. And there are films, I think, that are just much better with narration.

We’ve been very fortunate in the last few years to make films about the civil rights movement, and about Jonestown, where there are vibrant people who are around, who were part of it, who are alive and who can really talk about it. And so we’ve been able to say, “Let’s try this without narration.” I think it’s harder if you’re doing a film about Harriet Tubman. If there’s nobody alive, you never get that perspective.

To get back to the roadmap, have you ever had a situation where you started a film, thought you were pursuing one particular take on it (beginning, middle and end), and then along the way discovered something that shifted the film significantly?

Not that I can think of. Shifted the whole idea of the film? No. Because by the time we’re writing the script, we’ve already talked to a number of people. We’re pretty much there, especially with the historical docs. The personal film that I made, A Place of Our Own, that film totally shifted.

Can you talk about that?

The original idea was to do a film about black resorts—and there were different black resorts all over the country—and the idea of the history of these black resorts, and why black people would still go to these resorts. By and large, most of them started in the twenties, thirties, forties, whatever, during segregation, and these were safe places. But now people could go anywhere. “Why do people go to Oak Bluffs when they can go to the south of France?” was kind of the idea. And we couldn’t raise the money to get that done.

Then we found out about this program that ITVS had, an experiment, actually. They wanted to see if somebody could make a film, start to finish, for $125,000, every single penny. You weren’t supposed to raise any more money or anything like that. We couldn’t go to five or six different resorts for $125,000, so we shifted the film to be about Martha’s Vineyard. And that’s when A Place of Our Own became a film about Martha’s Vineyard, because that’s a place that I’ve gone to all my life. We realized that we could go there and put everybody up in my house, and do the film that way.

And then as we got the money, my mother passed away. And we kind of shifted a little bit to make a film about my mother and what happens when the matriarch of a family, who’s held the family together, passes, and what happens there. And then we shot that film and it just wasn’t working, wasn’t working, wasn’t working. We had to hire a new editor, and the new editor said, “Let me just look at all the footage that you shot.” And she said, “Well, I think there’s a film here, but it’s not really about your mother. It’s about your father.” And I said, “I think you’re out of your mind.” She said, “No, give me a week and let me just try to start putting some stuff together, and then let’s look at it.” And she did, and we said, “Wow. There is a story here.” Now, it took a long time to get this story to work and make this all make sense, but we did.

So that film went through a lot of different iterations, from being a film about black resorts in general, to being a film about Martha’s Vineyard, to being a film about my mother’s family in Martha’s Vineyard, to finally being a film that’s much more about my father and Martha’s Vineyard and family, all those things.

Your historical films are often very moving, because of the way they’re told and what they convey. A Place of Our Own was also very moving, but it’s a different kind of emotional storytelling. It’s obviously much more personal. What was that like for you as a filmmaker, to shift gears and do something so intimate?

First of all, it was an incredibly difficult film to make for me personally. This was the first and last personal film I ever made. There are a few documentary filmmakers who mine that territory; that’s what they do, and they’re good at it. But it was just totally a different process to make that film. And I can say that I had a lot of help. I needed a lot of help from the associate producer, from the editor, from Marcia (my wife), who wrote the film. It’s just really hard to judge. It’s very different to make that kind of film than it is to make, let’s say, Emmett Till, where Emmett Till gets on a train, goes down south, gets killed, they have a trial—all of those things have to be part of the film. Within A Place of Our Own, there was probably a time where every single theme that you see in that film was, at one point, out of the film. What has to be in the film and what doesn’t have to be in the film are very different.

You’ve worked with writers, co-producers, and editors. I’m curious about how you collaborate, and what the process is in terms of storytelling.

It really just depends. Usually the producers have certain tasks that are not so much the storytelling tasks, if that makes any sense. Their job is to find the people, put people in front of me, find footage, put footage in front of me, to know the story as well as I do, or even better than I do in some ways: to know the timeline, the dates, what comes first, what comes second, to know all those things. But usually it’s myself and the editor in the edit room. I just find that everything in the edit room is very, very, very fragile. Having someone else in the edit room changes the dynamic, changes the decisions that are made. But I try to be open to ideas from everybody who’s part of the process. So like in the Panthers, the assistant editor, who started as an intern, found footage of the Chi-Lites singing “Give More Power to the People” on Soul Train. And he said, “Hey, look at this.” That’s great; it’s actually how the film starts. So I try to be open to everybody kicking in ideas, but it’s my job to use them or not use them.

You’re the decider.

Yes. And your job is to not get offended and to keep coming up with more ideas. And that’s the hard part for people working on the film, is to be able to say, “I came up with ten ideas and none of them were used, but I’m going to come up with the eleventh idea.” That’s really important. That’s what we ask of people.

Let me ask you about the Producers’ Lab—and by the way, congratulations on the MacArthur!

Thank you.

Firelight Media, your company, created the Producers’ Lab in 2008. On the website it’s described as a “flagship mentorship program that seeks out and develops emerging diverse filmmakers.” How does it work?

The Producers’ Lab came out of the fact that I was getting calls and emails from random people, asking me to look at their project. Could they come in and talk about their project? And I have to say, part of it came from a film that I worked on years ago called Shattering the Silences, which is a film about minority college professors all over the country. And one of the things that minority college professors are asked to do, something extra that white professors aren’t, is to mentor people at random. We talked to one woman who said that the first day of class, she was in her office and she heard a knock on her door, and it’s like five black students who said, “We looked in the window and saw you here, and we want you to mentor us.” And it’s the same way, in some ways, for filmmakers of color. White filmmakers are asked to do this too, but I think there’s more of a feeling like, “I’m black, you’re black, I can call you up and ask you to help me out.”

So I was doing a fair amount of mentoring of filmmakers. Some of it came out of working with Byron Hurt on Beyond Beats and Rhymes, which was Byron’s first film and was very successful. Marcia and I helped him work on that film, and we just started thinking about how we could institutionalize the idea of working as mentors. It wasn’t only us. Sam Pollard, Marco Williams, a whole bunch of other people were doing this. How can we institutionalize this, and can this work? And so there were two main ideas that we had. One was that there are enough filmmakers of color out there with projects that are good, and with a little help they can get done and get on the air. And the other was that we could raise money independently to support this project. And I think both of those ideas have, at least at this point, proved to be true.

But the way it works, it’s really a mentoring piece. We work individually with the filmmakers and mentor them and try to provide other mentors. So we may look at their project and say, “Your sample is great. You need somebody to help you write the proposal. You may need a writer.” A lot of times people are working with editors who were their college roommate, who are competent editors but they’ve never really cut an hour-long film. So maybe they need to have an editing mentor, a supervising editor that we could pay for. We’re working with a filmmaker now who’s decided to make her film from a kind of historical film to a personal historical film. So [she] needs to talk to some people who have made personal films about: How do you do that? What are the tricks to make a film move into this kind of personal realm?

It really depends on the project, how we work with the filmmakers. Each project is very different.

And the Lab itself is very selective; filmmakers apply with treatments, a sample reel, production team bios and more.

It’s very rigorous. The projects that we accept in the Lab are films that can see the light of day. It may need a lot of work, but we can see this film getting done by this filmmaker.

There’s a conversation now in which filmmakers describe the boundaries between fiction and documentary as being increasingly fluid. I’m curious what you say when people talk about that.

I don’t know. I think in fact there’s a line somewhere, and films are coming closer and closer to that line. The stakes with documentaries have just gotten that much higher.

In terms of the marketplace?

In terms of the marketplace, yes. The marketplace, your career. . . You have people going from making a documentary to going to Hollywood. You have documentary filmmakers who have ambitions that I think traditionally documentary filmmakers have not had.

But at a certain point, once you cross the line, you’re actually making up stories.

Yes. Look, once the stakes get higher, it’s, “Can I do this? Can I do that?” And then the line starts moving. I think it’s a great thing that people are being more creative in documentaries. That’s a great thing. And that’s definitely happening. But there still have to be certain standards of: Is it documentary or is it fiction?

Sources and Notes

The website for Firelight Media is www.firelightmedia.tv/. The websites for films discussed include The Black Panthers, http://theblackpanthers.com/; A Place of Our Own, www.pbs.org/independentlens/placeofourown/; and Freedom Riders, Jonestown, and The Murder of Emmett Till can all be found at www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience.