Chapter 15

Alex Gibney

Filmmaker Alex Gibney founded Jigsaw Productions in 1982, and in the years since has produced films with partners including Participant Productions, Magnolia Films, Sony Pictures Classics, ZDF-ARTE, BBC, and PBS. The company’s website notes that Gibney is “well known for crafting stories that take an unflinching look at the political landscape of America.” When we spoke in 2010, his film Casino Jack and the United States of Money had just premiered at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival. Other recent films included Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson; Taxi to the Dark Side, the 2008 Academy Award winner for Best Documentary Feature; and Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, nominated for the 2006 Academy Award. For both Enron and Gonzo, Gibney won the Writers Guild of America award for Best Documentary Screenplay.

The list of projects completed since 2010 is extensive, and includes We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wikileaks, The Armstrong Lie, Finding Fela, and Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief.

We spoke by phone in March 2010, as Gibney was en route to catch a plane from New York to Los Angeles.

I wanted to talk particularly about Gonzo, Taxi to the Dark Side, and Enron. At first glance, these are difficult subjects: a deceased writer, torture, accounting. How do you approach a subject, and how do you begin to find a story within it?

In the case of Taxi, I was approached to do a film about torture, and initially reluctant because it was a very difficult subject and I wasn’t sure the subject would be a film. And so I looked for a story, and Dilawar’s moved me very much, the way [ The New York Times reporters] Tim Golden and Carlotta Gaul had told it. It had a strong emotional heart, and in a peculiar way, connected up this man [in Afghanistan] with Iraq, Guantánamo, and indeed Washington, just by following the threads. The people who were in charge of Dilawar’s interrogation in Afghanistan are then sent to Iraq just before Abu Ghraib. Once Dilawar dies, they send the passengers in Dilawar’s taxi to Guantánamo, as if to suggest that they’d really stumbled on a conspiracy, when these guys were nothing but peanut farmers. And then you get some sense that the Dilawar story was actually heard in Washington, D.C. And so finding ways to have that central story feather throughout the film, even as we’re dealing with McCain and Bush and Cheney and all of that other stuff, was critical. It’s one of the reasons I picked that story.

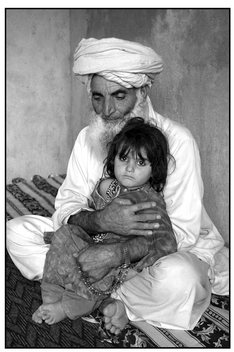

The father and daughter of Dilawar, in Taxi to the Dark Side. Photo credit Keith Bedford.

In the case of the other two, it was more about finding the themes inside the stories, and the characters are so rich. And even in the case of Taxi, to find the characters around the story of Dilawar, who was dead, that was hard. But that’s where the stories, I think, get good. It’s fleshing out great characters and seeing how they perform in action, just like a movie.

Are there strategies for how you do your research?

I have characters in my films who are journalists, so to some extent, I’m being introduced to subjects by people who have done a tremendous amount of research already. I want to honor that rather than pretend that I found it, when in fact they did. We also do a tremendous amount of research ourselves, so that at the end—and particularly if we’re taking somebody on—nobody can say that there’s anything that’s factually inaccurate.

Yet I also want to take that journalistic rigor and find a visual language, when telling a story, that will create what [filmmaker] Werner Herzog called the poet’s truth rather than the accountant’s truth. That’s why I have an argument sometimes with people in the audience who stand up and say, “Why don’t you just give it to us straight? Why don’t you take out all this junk?” I feel like what they’re really asking me to do is to show somebody at a blackboard with a pointer, going point by point by point through a story. I don’t find that very compelling. It doesn’t do what film does best, which is to engage people emotionally.

In other words, the subject itself is not a good movie—or a good book, for that matter. You have to put it together in a way that tells a compelling story if you want to reach an audience.

That’s right. What I do is similar to doing a nonfiction book. The best nonfiction books, in my view, are like good fiction in terms of their storytelling and their sense of narrative momentum. I lead the audience (hopefully) through some kind of unexpected emotional journey; this is where narrative issues come into play.

In the case of Taxi, a lot of viewers have told me that they came to identify greatly with the soldiers and liked them. And then at the end of the film, they found out they’re the killers, that they were convicted. And that was a blow to viewers, but they couldn’t go back to where they might have been if they had known that information to begin with, and say to themselves, “Oh, now I think they’re bad guys.” They couldn’t do that. “No, I like these kids.” That’s something more profound.

Knowing when to reveal information is part of the skill of good storytelling— too soon and it’s meaningless, too late and we don’t need it. How do you know when to fold in new information?

It’s a really hard thing. With Taxi, we had to discover some of that in the storytelling. The film wasn’t quite working for a long, long time. One of the things we realized was that we revealed the [prison] sentences of soldiers a bit too early in the film; it was toward the end, but not sufficiently close to the end. Once we revealed the sentences, the audience felt like the story was over and we’d better wrap it up. But we still had a lot of story, and that was just dead wrong. So we had to shorten the film and also move the section of the soldiers being sentenced further down, where it made sense in terms of expectations of narrative structure: Oh, we’ve concluded their story, so the film must be about to end.

Do you run test screenings periodically during the editing?

Yes, particularly when we get close. I’m doing that now on a couple of films. And it’s really important, because you learn a lot about what people don’t get, who they like, who they don’t like, obviously whether it’s too long.

Where do you find your test audiences? Who’s in them?

Usually it’s a combination of friends and a few acquaintances or friends of friends. It’s generally a reasonably friendly audience with a few strangers thrown in. But even in that audience, you can feel the room when you watch the film, and the reactions that are consistent among the viewers are the ones you most likely want to listen to.

There was a woman, Amanda Martin, who is the blonde executive [in Enron ], and in our original cut she ended the film with a kind of confession, in effect saying, “I was human,” meaning she was deeply tempted to become corrupt. But nobody wanted to accept her in that role. They’re thinking, “Human? Screw you. You profited from this company.” They weren’t prepared to hear that from her, because they saw her, very pretty, in this very opulent house, dressed in very expensive clothes. But they were prepared to hear it from that younger kid [former trader Colin Whitehead]. We thought the ending was beautiful, but they hadn’t seen in Amanda what we had seen in the cutting room. They could only reference what was in the film. So we took that bit out and put the kid in at the end, and people were much more comfortable with that.

Alternatively, you would have had to go back and restructure the film to get the audience to the point where they would have accepted her.

Yes, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. Also, peculiarly, what ends up happening—and this is the hardest part to accept as a filmmaker—is that the story you create has unexpected dimensions that you never imagined. And rather than extinguish them, you’re better off embracing them.

Can you give me an example?

Well, there were a lot of thematic issues I wanted to explore in Enron. And they were very meaningful in broader social context—for example, how the banks were complicit in Enron’s fraud. We have some of it in there, but we had to take a lot of it out because it was just stopping the narrative. None of that stuff would matter if people weren’t going to be riveted by the story. So it had to go by the wayside.

There is another example, in Taxi. There was a sequence which I love, which is now in the DVD extras. It was one of these weird side trips you take. [There was a] hunger strike at Guantánamo when we were there, and there was a desperate need to figure out how to break the strike. One of the things they were going to do was force-feed the prisoners who were on hunger strike, so they needed a way of restraining them. And lo and behold, some enterprising soldier at Guantánamo found this website called www.restraintchair.com. It turns out that there was a sheriff in Denison, Iowa, who was manufacturing restraint chairs to help calm people who were whacked out on crank, until they could reason with them, and to do so in a way that was not hurtful. So out of the blue, this sheriff gets a call from Operation Enduring Freedom saying, “We’d like to order 50 of your restraint chairs.” That was a big order for this guy. I found that sequence to be funny, and I went out and visited with him, and we had a great sequence about it. But ultimately, once we got to the death of Dilawar, there was very little interest by the audience in exploring that kind of dark humor in the film.

I had other Catch-22 moments in the film that, bit by bit, I had to excise because they couldn’t see—I had been immersed in this subject and had developed a kind of gallows humor that a doctor develops by being in an operating room all the time. But the audience couldn’t go there. They wanted to experience the anguish without irony, and I couldn’t rob them of that. So we had to eliminate a lot of that material that ultimately was distracting.

And just to clarify, that’s a different kind of omission than, say, leaving out the negative side of Hunter S. Thompson’s life, the pain he at times caused his family, just because you want to present a positive portrait of him.

Right. I’m not Hunter Thompson’s press agent. Interestingly enough, in the case of Hunter—and we talked about this a lot in the cutting room—I think his bipolar nature, the way he would vacillate between dark and light, the way he would be wonderfully generous and also very cruel, I think that allowed him to appreciate the essential contradictions of the American character in a way that somebody who’s more balanced probably couldn’t.

I wanted to return to the analogy between your films and nonfiction books, because you’ve also noted that in your films, as in books, you can hear the voice of the author. Yes, in terms of the style. Likewise, in a film, you have to find a visual language to carry the story. And that language should be different, in my view. There’re some people like Ken Burns, whose visual language is the same no matter what story they’re telling. The archival imagery may be different, but the style is exactly the same. To me, I think you find a style that fits the subject.

How do you decide upon a visual language for a particular film?

In Gonzo, we were wrestling with the fact that the guy’s a writer. And a lot of the visual style—that scene of the motorcycle at the beginning of the film, it’s overlaid with a kind of paper texture that’s meant to evoke, in an emotional way, that this is a kind of written story, even though we’re out there on a motorcycle with the surf. The other thing we were playing with was this blend that Hunter investigated between fact and fiction. He liked to rocket back and forth between them. He was a good reporter, at least early on. And then he would occasionally, for dramatic effect and also for thematic value, fly into fantasy. With something like the taco stand scene, we visualized it. That’s a passage that’s from the book [Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas], done in a way that felt true to their experience.

That’s an interesting example, because the visuals are created to look a bit like home movies, while the audio, as you note on screen, is an “Original audio recording by Hunter S. Thompson & Oscar Acosta, Las Vegas, 1971.”

Even though it’s fiction, it was much more realistically shot than some of the other material we used, which was nonfiction. We were playing with that mixture of fact and fiction that Hunter liked to investigate. [That] was one of the reasons we decided to shoot his wife Sandy against green screen. [Still and motion images of their history together play behind her as she’s interviewed.] She became the person that knew him the longest throughout his life. So rather than shoot her in a living room or a yoga studio—she’s now a yoga teacher—or something, there was something literary to me about seeing different backgrounds behind her, as if she were a character, literally, in a fiction or nonfiction narrative. So that she didn’t have her own space; she was inside this guy’s story. It wasn’t about, “Where are they now?” It was about, “Where were they then?”

That’s a kind of visual choice you have to plan for ahead of time.

Yes, you do. Sometimes you stumble into that stuff, but you do have to think about it beforehand. In Enron, we thought about it a lot beforehand, and certainly in Taxi, too. The way we shot the interviews of everybody who was at Bagram, the guards and some of the prisoners—they were shot against a painted backdrop and lit with high-contrast lighting, where you have one side of the face in light and one side of the face in dark. That was meant to do two things: to signal the moral ambiguity of the guards, but also, in a story that’s so complicated in terms of who’s military police, who’s military intelligence, who’s the prisoner, it was meant to convey one very simple idea, which is: anybody who’s photographed that way came from Bagram. And also that dark lighting had a kind of prison vibe, so that you create a sense of place. We had to think that out ahead of time, or else it never would have worked.

How much do you put on paper before you shoot? Do you have a basic narrative skeleton?

Yes, I think it’s fair to say that I have a narrative skeleton ahead of time. Not too detailed, but at least a sense of the story that is going to be told. And then I go out and try to talk to people, and occasionally shoot stuff on location, as in Taxi, because that was a story that in some ways was still unfolding. So I went down and shot a sequence in Guantánamo, for example. And then of course the story changes, and you have to reckon with that. But if you don’t at least give it some contour up front, then you don’t have enough focus, I think, to really dig in.

Do you write a treatment?

We usually have a treatment, but it’s not very long. It’s maybe three or four pages, like a general sense of structure. And with that in mind, I go out and get stuff. And sometimes I see an opportunity to get something that wasn’t in the plan, and I get it just because it seems like it might be great material.

There is a certain kind of filmmaking where you wade into an event and you just observe. But even there, it seems to me, you’re being influenced by your own preconceptions—what you know, what you’re hearing off camera—and you begin to focus on things that interest you. There was a lot about Enron that we could have gone into but didn’t, because I had a sense of what to tackle, what would be a good story. But, that having been said, you do improvise a lot, based on material.

Early on in my career, I had a much more rigid idea about what to look at and cover, and what I was interested in. I would tend to make the material fit my idea of the story. The problem with that is that sometimes you end up using a lot of rather weak material, instead of looking at what you’ve shot and realizing, “Man, this is strong,” and finding a way to include that material. If there’s not a kind of balance between those two things, then either the film is all great material but no narrative thrust, or it’s all story and theme and no heat, no passion. The key is finding the right balance.

In the case of Enron, we didn’t know exactly who was going to talk. If Rebecca Mark had talked to me—she was the woman who, among other things, had done the Bhopal initiative, which was a big power plant they tried to make happen in India—the narrative might have taken a slightly different direction. Also, halfway through the film [production], we discovered the California audiotapes. We spent much more time on the California story than the authors of the book did, and the reason is that those audiotapes told us something about the culture at Enron that was so powerful, and something that you couldn’t do on a printed page. Part of what makes them powerful is hearing the kind of “frat house” attitude of the people [Enron traders] laughing while the California grid goes down.

In Gonzo, the imagery is often quite unexpected. We see an actor as Thompson, for example, sitting at his desk in Woody Creek, Colorado and writing about the attacks on 9/11, as the attacks are seen—impossibly and very stylistically—through the windows in front of him. Or we’re looking at a still of Thompson holding a gun, and it suddenly becomes animated.

It’s looking at that in a playful way. Hunter really pushed the envelope of that kind of storytelling. As a filmmaker, I was trying to say right up front, “Beware.” So when you see that photograph of him shooting his typewriter in the snow and suddenly it becomes live, and you see the typewriter jump and then it snaps back into the photograph, that was a way of saying: “Watch out. Everything is not what it seems. There’s a kind of playful manipulation of reality going on here.”

When Hunter does his riff in the campaign trail book about Edmund Muskie being addicted to Ibogaine, I don’t think he really intended to fool his audience into thinking that “Oh my God, Ed Muskie is eating Ibogaine!” It was a playful, satirical way of saying to people, “This guy looks like and acts like he’s a drug addict. That’s how bad he is.” So again, it’s stretching the form, but in a way that, at its best, Hunter could do without violating larger notions of truth. I think later on it became sloppier in Hunter’s writing. But in his prime and in some of the best pieces later, he really used that to great effect, where there was great, real, factual material, but then there was a lot of playful stuff. And I think he laid out the rules so that you as the reader could get it. We tried to play with that a little bit in the visual storytelling.

You also lay out the rules. The dramatizations (or reenactments, or recreations) are styled in a way that distinguishes them from actual archival materials, for example, and when something is real—the taco stand audio, for example, or the Enron traders on the phone—you make that clear as well.

I think that’s pretty important. Sometimes I get criticized for recreations in my films. People say, “Why would you do such a cheap trick?” or something like that. Like the suicide of Cliff Baxter in Enron. I have a pretty careful explanation for why I did that. It may fool somebody at first, but then it’s very quickly revealed what’s happening, so there’s no attempt to deceive the viewer. I think that’s terribly important, because the idea of faking something and pretending it’s real is really a big, big problem. [Audiences] need to have a sense of trust that the filmmaker’s done their best to show you what they think the truth is.

There are different ways to the truth, and different kinds of truth. That’s why every filmmaker needs to have a different kind of an approach, a different set of rules. You let the audience in on those rules right off the bat; you signal people. If you do that and you follow those rules, then everything is fine, because then the audience gets comfortable with what you’re doing. The way Enron starts, both with the Tom Waits music at the beginning and also with that recreation, it lets people know this is not a Frontline, so you shouldn’t see it that way. The idea of creating a film that looks and feels like a Frontline but then mixes artificially recreated footage with regular archival footage and pretends they’re the same—that’s hugely problematic.

The actor Johnny Depp “narrates” Gonzo, but only in the sense that he is reading from Thompson’s work in voice-over—so he’s really a stand-in for Thompson, and we know that because you also filmed Depp reading with the book in his hand.

Right. That was a play on a lot of different things. Here’s the guy who played Hunter [in the dramatic feature Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas ], now reading Hunter. It also signaled to people in a very simple and clear way—because clarity is another thing that I’m kind of a nut about—that all the narration you hear from now on will be the undependable narrator of Hunter Thompson, as read by Johnny Depp.

What are your thoughts about current efforts to articulate some sort of formalized understanding about documentary film ethics?

That’s made me a little bit uncomfortable. If there’s some committee that decides what’s right, I could find myself on the wrong side of that committee. I think the thing to do is to make people think long and hard about why it’s important not to fool the viewer. But I would hate to go back to the old days where—I did a Frontline a long time ago. There was a prohibition against using music; music was considered a manipulation. And of course it is a manipulation. But it seems to me to be a pretty good storytelling device, and part of what you’re doing is telling a story. There are many fictional methods that I like to use. The key is creating a grammar so that viewers know you’re doing that, and don’t believe that you’re showing them a Frontline when you’re not.

The reason I put in the recreation of Cliff Baxter right at the top was because I felt that—First of all, you don’t know yet that it’s Cliff Baxter. It could be any executive. But you’re riding alongside somebody who’s listening to a Billie Holiday song [“God Bless the Child”], which happens to be very carefully chosen. It’s the kind of song he might have listened to late at night on the radio, but it’s also about how the rich and powerful screw the weak. You’re on the seat next to this person, smelling the cigarette, hearing the water going down his throat, and then he kills himself. And that’s very intimate—”Oh my God, somebody’s just killed himself!” That’s a very powerful human emotion. Then, when [the film cuts] to the archival footage, “Cliff Baxter was discovered dead today,” blah-blah-blah, you realize, “Okay, that was just a recreation. Now we’re in the real world.” What I tried to give to the viewer is a sense of identification with that executive, so we’re not there the whole time wagging our fingers at the Enron executives and creating too great a distance between them and us. We see the human dimension of this story in a way that’s very emotional and palpable. And to me, it’s perfectly legit.

That gets to a different aspect of your storytelling, which is that part of being fair as a filmmaker—not balanced in some phony way, but fair—is to allow for complexity, which includes seeing more than one side to a character or a point of view. In an interview you said, “I always take my cue from Marcel Ophüls (The Sorrow and the Pity) who said something like this: ‘I always have a point of view; the trick is showing how hard it was to come to that point of view.’” Can you explain?

There’s another quote that I like a lot, too. [George Bernard] Shaw once said, “Showing a conversation between a right and a wrong is melodrama. Showing a conversation between two rights is a drama.” A political science professor of mine would say, “Embrace the contradiction.” All those things to me mean that if you find somebody that you think is kind of a bad guy, and then you only show that stuff that fits your preconceptions of who that person is, or the role they’re playing, [that’s] a kind of melodrama. Much more powerful is a drama, in which that bad guy is actually, in person, kind of a nice guy. Or you’re surprised to learn, for example with the guards [at Bagram], these guys who beat a young kid to death, are young kids themselves who, in their own way, are nice guys that have been brutalized by the experience. That, I think, shows a kind of hidden dimension that connects us all together, which is part of what filmmaking and storytelling is all about. It doesn’t necessarily undermine the moral outrage, but it makes it tougher to point at people and say, “They should wear the black hat, and I wear the white hat.”

I try not just to preach to the choir. A lot of times people will come to seeing your point of view, or at least to appreciating your point of view, if they feel that you have respect for theirs. You may not agree with it, but at least you have respect for it and have tried to reckon with it. I think that’s important, because otherwise we’re just in some kind of endless loop of crossfire from the left, from the right. Ugh. What could be worse?

There are a couple of very pragmatic things I want to talk about. The first is the way that you visualize scenes, creating a strong sense of place.

I like the idea of creating visual beds, particularly in a complex story. An example would be the strip club which [Enron executive] Lou Pai used to inhabit. We shot it in a way that emphasized numbers, and we cut it to music by Philip Glass. We tried to shoot a sense of the place of the California trading floor too, and find music and a shooting style that would convey the frat house atmosphere, to portray it from their point of view. So those are two examples. [Someone else] could have done it very differently.

The other is sequences, which you sometimes name, such as “Shock of Capture” in Taxi to the Dark Side. Your films are built on sequences, each of which has a unique job to do in the overall film, and each—while different from the others—moves the film forward.

That’s right. I find that helpful, and then if you vary the manner of the sequences, too, it keeps the audience fresh. You keep moving from one place to another, like you’re on a journey. It’s like a bus tour: We’re leaving the Grand Canyon, and now we’re headed for the Rockies.

And you’ve arrived at the airport! Thank you so much.

Delighted. I rarely get to talk about form. When you’re a documentarian, the curse is, you almost always only talk about the subject, which is okay, but in terms of documentaries in the last 15 years, I think one of the great things that’s happened is that the form has just exploded, which I think is really exciting.

Sources and Notes

The website for Gibney’s company is www.jigsawprods.com. The official website for Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson is www.huntersthompsonmovie.com. Interview with Alex Gibney by Alex Leo, “The Gonzo World of Alex Gibney,” The Huffington Post, posted July 3, 2008, www.huffingtonpost.com/alex-leo/the-gonzo-world-ofalex-g_b_110695.html. The website for Taxi to the Dark Side is www.hbo.com/documentaries/taxi-to-the-dark-side. For more information on Taxi to the Dark Side, see also Tim Golden, “In U.S. Report, Brutal Details of 2 Afghan Inmates’ Deaths,” The New York Times, May 20, 2005, online at www.nytimes.com/2005/05/20/international/asia/20abuse.html. Information about Enron can be found at www.pbs.org/independentlens/enron/film.html.