MULAN

My Mulan story begins in September 1993. At that time, I was still working in London at Spielberg’s Amblimation studio. I was production designer/art director on Balto. Andreas Deja, a good friend and former student in Germany, now one of the top animators at Disney, had called me and talked about a future project they were planning: China Doll. He explained the showdown between the emperor, Mulan, and her army friend. I liked that ending actually way more than the ending in the final film. It was a mix-up story, where Mulan had to decide between the life of the emperor and her friend Shang. Anyway, that story sounded too good and it was set in China! What an opportunity for designs in a very new style, mysterious, poetic, and exotic. And I was stuck in London in that icy Alaska movie. Well, I bought some books about Chinese art, because I had no idea about that part of the world and their culture. The more I read and the more I saw, the more I got trapped!

I started to do some sketches, just for myself and without Disney knowing about it. Funny thing is, Barry Cook, the first Mulan director, saw these designs later and they made him decide that I was his first choice to design the entire film.

Well, in March 1994, I left London and the Amblimation crew. Mulan was not the reason. It was the very uncertain future of that studio. Nobody wanted to tell me any details of Spielberg’s plans. About a year later, I understood

why — he started DreamWorks together with Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen in Los Angeles. And most of the artists I had worked with in London moved to LA and worked “next door.”

I moved with my wife Hanne in June 1994 to LA and started to work at Disney, the first time in my life I was employed there. A new experience! My first projects as visual development artist were Hercules, Fantasia 2000, The Steadfast Tin Soldier, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, and Dinosaur. Mulan already had a development crew that had been working on it for nearly one year. Among them was Chen-Yi Chang, who later became the character designer of the movie and my good friend. I could not have designed Mulan without him. He very patiently explained everything about China, gave me the real books and background information — and he knew the best Chinese restaurants in town!

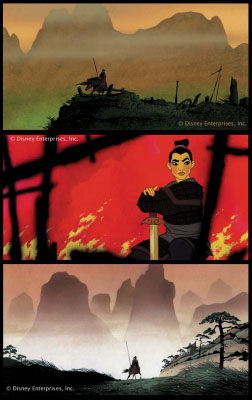

The Mulan visual development team had problems with the style. They tried to copy Chinese water-color paintings, but did it the Disney way, with tons of detail everywhere and were kind of lost. Barry Cook, the director, asked me in December, 1994 to take over as production designer. That was a challenge. I had no clear idea where to go, but I knew I didn’t want it to look like the recent Disney movies, for example, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and The Lion King. My dream was to create a look that was more similar to my favorite older masterpieces.

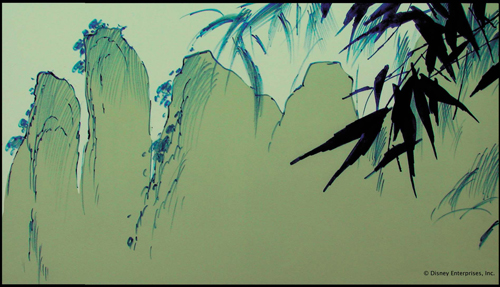

Chen-Yi had shown me some original Chinese comic books. Each about 300 pages thick, with very delicate black & white drawings in some styles I had never seen before. They showed a very unique way to draw trees, mountains and villages. Not to mention the human characters, animals and props.

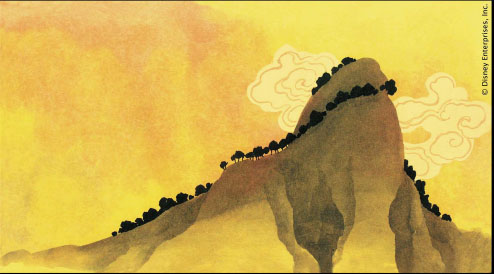

They were fascinating. In a way they completely changed my design thinking. Then I noticed that in most of the separate hundred-year-old watercolors, there was something that made them very typical. It took weeks until I finally understood. It was the lack of perspective and fine detail. It made them look very flat.

I immediately started to use that experience in my own designs. Their size was very small and that is what helped. The bigger you draw or paint the more detail you want to add. Because of the small thumb-nail size of my color sketches I did not even think about that. Later during the production, I asked the background painters to throw all brushes below size four away. Detail was not allowed.

These preproduction years 1994-1996 were incredible! When you are used to working in the advertising or TV-world you are not used to the luxury of having all that time, time to search for something, though you don’t quite know what it is. It’s a luxury only a few studios can afford. And it might only have worked in those years because it was the ‘Golden Nineties’ in animation after all those successful hits.

The studio gave me the chance to invite guest-artists’ from all over the world. We wanted to explore all different talents to add more ingredients for a unique look for our movie. Among these artists were — Alex Nino, a comic legend from the good Marvel days. Born in the Philippines, and living in LA -what an artist! I still don’t understand how he works. He starts in one corner of a large A2 paper and finishes it in the afternoon with the most incredible scenery showing action and mood and without one rough sketch line. It’s all in his head. Then, Regis Loisel, best known

for his comic adaptation of Peter Pan has a completely different style. What an artist, again! I felt so honored to have had a chance to work with them and to have fun together. Others were Vink, a Belgian/Vietnamese comic artist and Harald Siepermann, my comic strip partner of the A. J. Kwak series and former student. All those artists contributed their view to a growing huge package, a collection of Mulan ideas.

There must be thousands and thousands of sketches in the Disney archives from that time. Every single sketch was discussed together with the two directors: Barry Cook and Tony Bancroft. We decided together what we should use and what was going in a too different art direction.

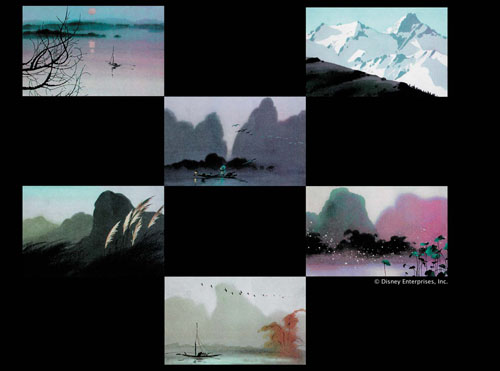

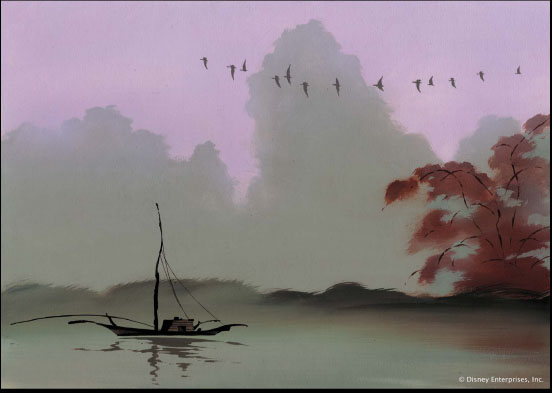

At the same time, I was diving into the world of art. I had never done that before, because there was never enough time. Job delivery next day! Now I found out about all these artists of the past, completely unknown to me, not through books, but through auction catalogs from Sotheby’s and Christie’s. I also found them used and inexpensive in the numerous LA flea markets on the weekends. After some years, I had collected 1,500 of them; I specialized in Chinese art of course, in Impressionists, nineteenth century and modern art. After a while, I selected a few from the thousands of art pieces that I thought I could use as inspiration for our movie.

There was Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, a French painter from the Barbizon school during the eighteenth century. Beautiful washes in oil, no detail at all — mood! mood!! — more like matte paintings for a movie. From a distance they made sense. There were some more, such as Franz Richard Unter-berger, who worked in Belgium during the Nineteenth century;

Eugene Galien-Laloue, who worked during the same period, with his precise architectural paintings of Paris; and, opposite Giovanni Boldini, an Italian painter with his rough expressive style. And of course all that Chinese art from the last four centuries. Including calligraphy -beautiful. I learned about the

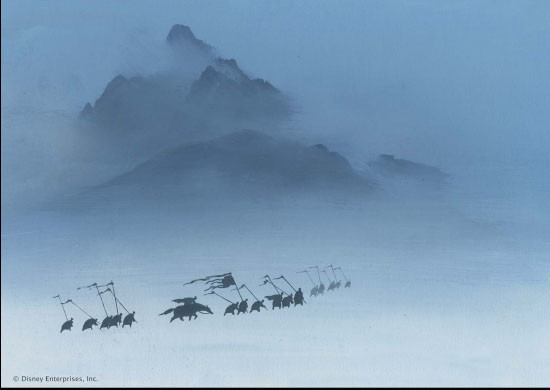

philosophy, the Yin and Yang, the balance everywhere that influenced all those amazing landscape washes with detail in some areas, but more like texture, and more and more detail toward the foreground in the very stylized blossoms, bamboo and grass. Exactly what I wanted to see in the movie.

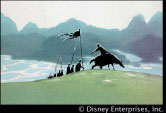

But I knew that too much art would destroy the acceptance by the audience. An audience wants to be entertained, not educated. So, what we had to come up with was the feel of China embedded in a commercial Disney movie.

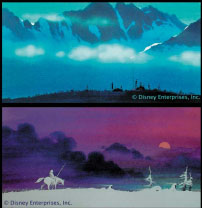

Somehow we had to find a way to make the movie look like a Disney movie. Not like The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast or Hercules. More like the masterpieces of the old days like Bambi and Pinocchio, even the Silly Symphonies. The Walt Disney Archives contains the “Animation Research Library,” and Lella Smith and her crew were especially a big help going through many original backgrounds and layouts of these milestones in animation.

Its hard to explain how you feel when you hold one original background from Pinocchio, painted such a long time ago, in your hands. We were nearly whispering like you would in a church. Those guys back in the Forties did not know what they had created: the water-color backgrounds of the Silly Symphonies, Pinocchio, Dumbo, Fantasia and a lot of the others, and the oil painted forest scenes of Bambi. There was no unnecessary detail. They were pure empty stages for the action to follow.

I still get goose bumps when I remember the beautiful layouts in Bambi, graphite paintings, masterpieces; everything was right, the composition, the mood, the translation of reality. That’s what we needed. But nobody was there to teach us. The only way was to analyze the old work on Bambi, Pinocchio and especially these golden rules for our movie. That’s how my Style Guide for Mulan started.

Ric Sluiter, who was assigned as art director, was working very closely with me. He is a master painter in all techniques: Watercolor, oil and gouache. And he explained to me how these guys had painted. The secrets! I was called during the London time “the magic marker

wizard.” That was the technique I had used for years. It was fast, dirty and dangerous. But the final artwork looked very close to a printed piece of art and the colors were vibrant. I was pretty good in all the different ways to fake a watercolor look. Thats how I had done all the hundreds of designs for Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and Hercules and now for Mulan. But I realized I needed to paint big, in the original painting style, in gouache. I needed to show what I thought the backgrounds should look like in a technique everybody could follow.

The little thumbnails I had done always looked a bit out of focus. That effect was very hard to copy when blown up to a bigger size. So Ric explained a very old technique to me, working with a badger brush. The dry brush softens the edges of the fresh applied color to the cardboard. I was fascinated by that technique. The same night at home I tested it and finished my first three backgrounds in a size twelve field. They became the first designs to define the final style of the movie.

In 2006, I had a chance to go to China for the first time. I was invited to give some lectures at two universities. It was amazing. All the students I met knew our movie and liked it. And I could see some of the beautiful treasures this country had to offer. I visited more than ten years after I started work on the film.