It is the greatest shot of adrenaline to be doing what you have wanted to do so badly. You almost feel like you could fly without the plane.

—CHARLES LINDBERGH

5

Time-Release Motivators

Dreamcrafting isn’t exactly rocket science, as we’ll be the first to admit. Ironically, though, when it comes to sustaining motivation, a little understanding of rocket science can actually help a great deal.

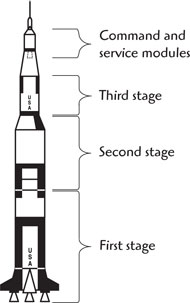

The Saturn 5 rocket (used to launch the Apollo lunar missions) stood 360 feet tall and weighed 3,000 tons when loaded with fuel. This forty-five-story cylindrical object was not one single hollow fuel tank, however. The rocket was divided into three separate “stages,” each with its own entirely separate propulsion system.

The first stage (the lowest part of the rocket assembly as it stood on the launch pad) contained 2,200 tons of fuel—nearly 75 percent of the total. Does this mean the first stage propelled the astronauts nearly 75 percent of the distance to the moon? Not quite; in fact, the first stage fell away from the assembly, its fuel supply entirely spent, at an altitude of no more than forty miles above the earth. This was the amount of fuel required to overcome the earth’s gravitational pull from ground level.

96The second stage carried some 460 tons of fuel—about 21 percent of stage one’s fuel load—yet was able to almost triple the astronauts’ altitude to well over a hundred miles above the earth, before separating and drifting away.

Stage three carried “only” 115 tons of fuel—less than 6 percent of the first stage—but this was enough to propel the astronauts out of earth orbit entirely and into a lunar trajectory before it too was jettisoned.

The service module that housed the astronauts for the rest of their voyage to and from the moon carried one-tenth the fuel of the Saturn 5’s third stage, and approximately one two-hundredth the fuel of the first stage. This vehicle, the service module, was really the rocket that transported men to the moon and back—yet it seemed downright puny in comparison with the monster required to lift it free of the earth’s pull.

97Or, to restate much the same thing in the more down-to-earth terms of the basic law of conservation of momentum: it takes a lot more energy to get something going from a dead start than it does to keep it going once it’s moving.

Success in Stages

This is a useful principle for dreamcrafters to bear in mind because it also applies in a variety of less mechanical, more abstract human contexts. In hypnotherapy, for example, the therapist may need to make a concerted effort over quite a long while to get a first-time patient sufficiently relaxed to be open to hypnotic suggestion; but once the hypnotic state has been achieved, deepening the trancelike state requires ever-decreasing effort on the part of the therapist. Eventually a single word, or even a snap of the fingers, may be enough to induce a deep hypnotic state in this patient, or bring it to an abrupt end.

This principle is the key to the riddle of sustaining motivation. Those who cling to the no-willpower myth are almost invariably interpreting their loss of motivational momentum as some sort of personal character flaw. In most cases, however, their motivational “launch vehicle” consists of only a single stage. Their “moon rocket” is one solitary fuel tank, like the Saturn 5’s first stage all by itself. Ignite the fuel, and for a time it burns impressively hot and bright—until the fuel supply is exhausted, and it falls back into the sea. In the absence of a motivational second or third stage to propel them the rest of the way, they too fall figuratively back to earth, overcome by the gravitational pull of the status quo, mission unaccomplished, their failure pattern reinforced. And as a rule, if they failed to develop such a second- and third-stage strategy at the outset, it is only for the very simple reason that they did not know they were supposed to.

98Multistage rockets like the Saturn 5 operated on a “time-release” basis—that is, the power of the second and third stages was not activated until well after the initial liftoff, not in fact until certain very carefully predetermined points in the flight trajectory had been reached. When Apollo missions were covered on live television, the on-air commentators would routinely count down to these critical points in the flight: “We’re now one minute and fifteen seconds from staging…” It was always exciting to observe (even if only in animated simulation) when one stage shut off and the next one kicked in, thrusting the astronauts forward at even greater speed toward their lunar destination.

Dreamcrafters must design similar time-release stages into their own motivational strategy. Thinking of their entire “flight path,” from initial declaration of the mission to the moment of triumph when the vision of success becomes a reality, they must identify one or more critical “flight milestones,” and designate these as the “staging points” where a new and untapped source of motivational energy will kick in to propel them further forward.

Note that even though the Apollo service module carried only a tiny fraction of the Saturn 5’s total fuel load, this still represented over ten tons of fuel! This little engine had a lot to do to make the mission a success. A breakdown in any part of the “puny” service module had life-and-death implications, as was skillfully dramatized in Ron Howard’s movie Apollo 13. Similarly, though it may take less effort to keep the dreamcrafter’s motivational engine moving once it’s set in motion, failure to do so—and to do so correctly—places the mission, the Big Dream, in deadly peril.

It means the “staging points” must be defined with precision. If the Saturn 5’s stages had cut in too soon or too late, the astronauts would have undershot or overshot their trajectory window, with catastrophic results. The dreamcrafter must similarly know the best points along the path to success for the motivational booster rockets to kick in, or risk not reaching the destination at all.

99This in turn means defining the means by which the flight path will be monitored, the means by which movement toward success will be measured on a continuous basis. In other words, an appropriate tracking system must be devised.

Road Map for a Dream

Name any city separated from your door by many hundreds of miles of roadway. If your mission was to get there by car, would you wait until you’d driven the requisite number of miles and only then confirm that you’d been driving in the right direction? (“Gosh, each day seemed to be getting a little warmer than the one before—I could have sworn I was heading toward the equator!”)

The dreamcrafter has defined a mission with great precision. To sustain motivation, the tracking system that’s called for is one that answers, with equal precision, the question, “How will you know you’re getting closer to success?” (Or, how will you measure your progress, day by day, so that you can make any appropriate midcourse corrections as the need arises? Or, what will tell you you’re moving in the right direction?)

Obviously, any serious dieter will own a reliable bathroom scale. So when we refer to a tracking system to monitor progress, does this translate—in the dieter’s case—into a good bathroom scale? Emphatically not. A scale measures weight, not progress.

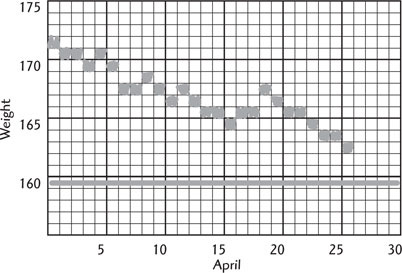

For a dieting dreamcrafter, an appropriate tracking system might involve sheets of graph paper, each representing a calendar month, with the target weight for one of the stages indicated by a bold line, as illustrated on the next page. At the same time each day, the dieter steps on a scale and then inscribes weight against date by filling in the square that lines up with both axes. (As part of the staging strategy, once milestones have been reached, the dieter may choose to create new charts in which the vertical weight axis is broken into half-pound increments, just to keep progress highly visible on the charts.)

100

The hallmark of an effective tracking system is its ability to reveal not only successions of numbers (raw numerical data) but also trends and patterns at a glance. (An observant dieter may detect regular spikes every Monday, following lavish Sunday dinners, and a huge upswing right after Thanksgiving, for example.) If our dieter were instead to inscribe each day’s weight into a notebook, say, all he or she would end up with would be one or more columns of look-alike numbers; very difficult to extract any trends or patterns from that. Yet most dieters don’t even do that much; they record no data at all, and are content to rely on their memories for information on their progress.

If a dieter’s mission is to improve health as well as lose weight, then the tracking system may monitor progress in other dimensions as well: blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and so on. The objective, again, is to be able to readily assess progress toward successful achievement of the mission, whatever that mission may be. As with a road map, the tracking system clarifies the location of “destination” relative to “current position,” and makes it easier to monitor movement between the two.

101The charts or graphs or toteboard or “thermometer” or whatever you’ll use to track your progress should then be posted where it can easily be seen and interpreted—and not just by you. As part of the declaration strategy discussed in the previous chapter, you want those around you to discover from these measures just how determined you are to succeed, and you want any cynics or naysayers in the crowd to see firsthand how your positive results are already threatening to disprove their predictions of failure. This, too, translates into a source of motivational energy, since you’ll feel a strong compulsion to avoid posting results that seem to support their negative expectations.

Of course, from time to time your results may genuinely appear to be heading in the wrong direction. When this happens, your tracking system becomes an early warning system that immediately alerts you to the fact. As part of your never-ending declaration process, you can then share with those around you your concern about the trend, and your strategies for making appropriate midcourse corrections.

Once the right tracking system has been devised, a dreamcrafter can determine where the staging points should occur along the path between the current position and destination. That is, where are the key milestones along the journey? Where would an extra boost of determination come in particularly handy? Where are the appropriate opportunities to pause and celebrate the progress made thus far?

This is the time-release strategy in a nutshell. We devise a tracking system that will accurately monitor our progress, we determine the staging points where motivational boosters would be most beneficial, and we celebrate our achievements at each staging point.

The key to sustaining motivation: track progress and celebrate key milestones.

The locations of these staging points may be arrived at purely arithmetically—the halfway point, the two-thirds point, and so on—or through some other rationale (such as, “I know the very final stretch will be hardest, so I’d better schedule a motivational booster right before it begins.”). The number of staging points depends on the time frame of the mission itself; in most cases, though, one or two should be enough to do the trick.

102It is the celebration aspect at these key milestones that will generate the motivational fuel required to power the booster engines in remaining stages. The more skillfully these achievements are celebrated, the greater their motivational effect.

Rites of Passage

Graduations, weddings, funerals, anniversaries—these are the stuff of our photo albums, and of our album of memories. For events like these we somehow find ways to alter our normal schedules and make time to be present, even if considerable travel and other logistical complications are involved. We do not dress for such events in the same kinds of clothing we wear every day; these are special occasions, and must be treated as such. And for those whose rite of passage we are marking, the clothing is often even more special; most wearers of graduation robes or bridal gowns assume these will be worn only once in an entire lifetime.

Each of these occasions has certain ceremonial or ritualistic traditions associated with it. The participants will feel slightly cheated somehow if these rituals are not honored. Ceremony, after all, is the whole point of the exercise. It is a basic function of what we describe as “society”— someone within a social group makes a passage from one stage of life (student, single person) to another, and others from within the same group mark the passage with appropriate ceremony and celebration. And note, in many cases it is those making the passage who determine how it will be marked, and by whom. The bride herself, for example, typically dictates how big the wedding is to be, recognizing that bigger usually means not only more guests, but more formality—that is, more emphasis on ceremony.

103Of course, some graduation ceremonies, or weddings, or other rites of passage “come off” better than others—which is to say, in some way they seem more satisfying for all involved. The way applause is handled is an example of a skill-related issue that can affect the success of such a celebration.

Anthropologist Desmond Morris suggests that applause represents collective back patting from a distance, a way by which each member of an audience can convey, “This is what I would be doing on your back if I could be holding you in an embrace right now.” At a wedding reception, the master of ceremonies formally introduces the newly married couple as they enter, and they are greeted with enthusiastic applause—the affection and congratulations of all present delivered at the same moment.

Show business professionals are obviously the most skillful receivers of applause. They can “feel the love,” and live their whole lives in pursuit of this elixir. Circus performers, such as trapeze artists, conclude every move with the same flourish—one or both arms extended upward to receive a huge embrace from all—and the audience dutifully responds with a renewed wave of applause. At the conclusion of a play or concert, the performers will continue taking deep bows for as long as the applause holds out. In show-biz, the more the audience loves ‘em, the more performers are inspired to give; and the more they give, the more the audience is inspired to love ‘em.

We “more modest” folk, however, can feel somewhat embarrassed to find ourselves receiving the applause of others. When compliments come our way, we tend to deflect or dismiss them as if they were somehow inappropriate; when applause breaks out, we put up our hands in a blocking gesture to bring it to a quick end, or scoot out of the spotlight in a hurry. Thinking at that moment that we are being nobly humble in some way, we may in fact be depriving those who are applauding us the opportunity to express the full extent of their appreciation for our achievement. It can make them feel cheated, which contributes to a sense that the event didn’t really “come off” quite as well as it might have.

104From a dreamcrafting point of view, applause (and the support it symbolizes) plays an important role in sustaining motivation. Each staging point should be treated as a special occasion, a ceremonial rite of passage marked with celebration and support. The splashier the ceremony, the greater the motivational return. Even if there is to be only one other person in attendance, the return can be significant—and if it feels comfortable to involve a larger number of participants, so much the better. Ideal attendees are, first, anyone who has “been there,” who has successfully traveled a similar path in his or her own life, and is thus equipped to appreciate the significance of your achievement; and second, any and all who wish you well on your journey.

The “public event” itself may be as informal as a casual get-together at home, or as lavish as a fancy dinner and evening in some fashionable venue. (Though if the event is specifically to celebrate weight loss, a big fattening meal may not be the ideal forum; similarly, let’s not mark our success at breaking an addiction to nicotine by handing out cigars.) Whatever the nature of the event, a number of steps can be taken to make it feel more special for all concerned. Invitations, for example, should be produced on paper and mailed, even if recipients have already agreed to attend in prior conversation. Provision must also be made for someone (even if only a waiter) to take photos of this historic occasion. (Such photos should be put on display right alongside your tracking mechanism, one more element in your unending process of declaration, one more visible reminder of your determination to succeed.)

Any number of creative elements can be brought into play to make this celebratory event more memorable. You may want to encourage attendees, for example, to bring along inexpensive gag gifts that in some way relate to your achievement. (For the dieter, for example, perhaps some laughably unattractive underwear with a preposterously narrow waist to “continue to aspire to.”) Participants should also be encouraged to make toasts—and even, if anyone feels so inclined, to deliver a little speech. (“I’ll admit it, at first I didn’t think Chris had a chance of making it this far …”) For your own part, try to think of some icon that represents the previous stage, which you can ceremoniously destroy to symbolize your transition to the next stage. (For the dieter, perhaps a favorite well-worn old shirt that is now far too large gets shredded into dust rags.) Be sure this symbolic moment is captured in photos. You might even place a personal ad in that day’s edition of your local newspaper, worded as if it were a news story reporting your achievement, which you could have someone read aloud to the group; or (fake) messages of good will might arrive from various celebrities or public officials. If your tracking system relied on some sort of toteboard or graph, you may want to make a ceremony of retiring it and unveiling its next-stage successor in a bold new “stage two” color scheme.

105Bring your celebration to a formal close by continuing your process of declaration and outlining what stage two holds in store for you. Treat attendees as your personal support group, and invite them to propose ideas for the next celebration, once the next milestone has been reached. And when the group applauds, let them! Savor the moment. Draw energy from it. That wonderful feeling you’re feeling is your motivational engine becoming recharged.

Quiet Time

The recharging process can continue privately as well, after the public celebration is concluded. If, for example, you’re looking for a place on the calendar to slot a vacation anyway, you may enjoy rediscovering why the wedding ceremony is traditionally followed immediately by a honeymoon getaway.

Ever notice how some vacations, like some ceremonial celebrations, just somehow seem to come off better than others? Even when all the external factors—weather, accommodations, attractions—seem about the same, sometimes vacations are deeply rewarding times of renewal, and at other times we seem to return to our regular lives as weary and frazzled as before we left.

106Perhaps there are occasions when the calendar says it’s time for a vacation, but the heart feels differently. A sense of “unfinished business” may in some subtle way make the timing of a scheduled vacation seem somehow inappropriate. Maybe those rare, sublime getaways that leave us renewed and refreshed typically coincide with a feeling of having completed something important in life, a feeling that “I deserve this, I earned it.” As former chairman of the department of psychology at the University of Chicago Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi explains in his book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, some of the most profound forms of human satisfaction derive from having successfully achieved a challenging goal—any challenging goal, as long as it holds meaning for the person who achieved it. There is no better time for reflection and renewal.

Even if it’s not possible to get away from it all immediately after the staging-point celebration, it’s worth trying to get away from some of it— for a long weekend, for a day, for a few peaceful hours at the very least. However much time can be commandeered, it’s important that it follow as close on the heels of the celebration as possible; a “belated honeymoon” never has anywhere near the same effect.

This is the blissful quiet time, free of all agitations and preoccupations, during which a dreamcrafter says to himself or herself, “Holy [expletive of choice], I actually did it! I really do have enough willpower! I really am going to make this dream of mine come true!” While public declaration is for the purpose of reprogramming prospective naysayers, this quiet internal declaration serves as further personal reprogramming.Any residual shreds of pessimism and self-doubt are put to rest for good. Where the motivational effect of the public celebration increases energy and power, this private meditation serves to simultaneously remove lingering internal obstacles and blockages. This is a time of “recreation” in a very literal sense. Rather than allow these rare, sublime moments of peace and clarity to happen by happy accident, the dreamcrafter plans for such times in advance, to coincide with the staging points at key milestones—and resolves to linger in the blissful moment deliberately and purposefully when it arrives.

107This time of recreation—even if it should happen to fall during a well-scheduled vacation—should not be mistaken as a reward for achieving one stage of the mission. To the contrary, this period of rest and renewal is itself an important part of the overall mission, key to sustaining motivation.

A little separate self-reward, if skillfully administered, can add even more fuel to the motivational booster engines.

The Reward Trap

If you finish all your green beans, I’ll let you have some ice cream.” This is the reward model we have all grown up with. Do something unpleasant and your reward will be something pleasant—bribery, pure and simple.

The problem with this approach is that it can alter perceptions on both sides of the equation. In the example above, it can reinforce a child’s perception that green beans truly are nasty things, since a reward is necessary for their consumption, and ice cream truly is the most perfect form of nutrition for the human animal, since it is so often offered as the supreme reward for eating nasty stuff. An experiment conducted at Stanford University and reported in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in 1973 illustrates the phenomenon. Preschoolers in one group were told that if they consented to draw using felt-tip markers for a while, their reward would be unlimited use of pastel crayons thereafter; those in a second group were told the opposite—pastel crayons for a while, felt-tip markers as a reward thereafter. Weeks later the researchers observed which kind of drawing tool the children favored when the choice was entirely their own. In almost every case, the kids preferred whichever type had been designated their respective “reward.” The conclusion these and many other researchers have come to is that “extrinsic rewards tend to reduce intrinsic motivation,” as Alfie Kohn puts it in his book Punished By Rewards. In other words, anything held up as a reward for something else tends to devalue that “something else.” One way to avoid this is to offer rewards that make the “something else” itself easier, or more fulfilling, or more satisfying in its own right—that is, an intrinsic reward.

108It’s an important lesson for dreamcrafters seeking to sustain motivation. It means, for example, that the best way to reward progress in a weight-loss initiative is not to buy some extravagant new item of clothing in a smaller size. For most people, properly fitting clothes are a virtual necessity, likely to be purchased sooner or later in any event. The more effective intrinsic reward for having met a weight-loss objective is one that makes the process of losing weight a more satisfying activity in and of itself. If the pounds were shed through dieting alone, this could mean some fancy new kitchen appliance that will make the preparation of special foods more enjoyable, or perhaps a lavish coffee-table cookbook with recipes that support the diet in question. If exercise played a part in the weight loss, this might mean an elaborate piece of exercise equipment is in order, or perhaps a music system that can be used while exercising.

For a writer who makes an important sale for publication, an appropriate self-reward might involve a more comfortable workstation at which to write, perhaps, or an upgrade to his or her word-processing program. For a musician with a dream, it might be a better instrument, or perhaps instruction from an acknowledged master.

The object of self-reward during this rite of passage, remember, is to sustain and even amplify the motivational drive to complete the next stage. Anything that helps make that next goal easier or more pleasant to achieve qualifies as another time-release motivator.

As part of the declaration strategy, the reward should always and forever be linked to the achievement it honors. Not, “This is my new food processor,” but rather, “This is the food processor I gave myself after I lost my first ten pounds.” It becomes one more way to remind those around you that your dream is in the process of becoming a reality right before their eyes.

109Time-release motivators are those boosters-of-determination that dreamcrafters plan for at key staging points in their overall flight plan toward the vision of success. This kind of planning for the future becomes easier when we cultivate the ability to live with one foot in tomorrow, as we’ll see next.

GALLERY OF DREAMCRAFTERS

CHARLES LINDBERGH (1902-1974)

The Big Dream

While still in grade school, Charles A. Lindbergh displayed unusual mechanical aptitude. He was able to take apart and reassemble a shotgun almost before he could read. At age nine he astonished a hardware merchant with his understanding of the workings of pumps and gasoline motors. He loved excitement and adventure and relished the heroic stories of wartime fighter pilots. The notion that he might become an aviator began to take hold of his imagination.

Bored with school, Charles dropped out of the University of Wisconsin just before his twentieth birthday. He signed on with the Nebraska Aircraft Corporation, where he hoped to learn all aspects of airplane construction, maintenance, and operation. By 1923 he was an airmail pilot, barnstorming his way around the Midwest.

Lindbergh soon tired of mail flying, and dreamed of capturing the $25,000 prize (offered by the Frenchman Raymond Orteig) to the first aviator to fly nonstop between New York and Paris. Charles began searching for financial backers to sponsor his flight. Time was short; several other teams of pilots in the United States and France, including U.S. Navy Commander Richard Byrd, were preparing transatlantic flights of their own.

110On May 20, 1927, despite little sleep in the previous twenty-four hours, Lindbergh took off from Long Island’s Roosevelt Field in his plane Spirit of St. Louis. In an audacious gesture of declaration that left little doubt about his determination to succeed, his entire store of provisions for the voyage consisted of nothing more than a few sandwiches. He flew the 3,600-mile distance between New York and Paris alone in thirty-three and one-half hours. Crowds surged toward his plane as it touched down in Paris.

Overnight, twenty-five-year-old “Lucky Lindy” became the most famous man on Earth, and thanks to radio the first “instant celebrity” in the new age of mass communication. More than four million people participated in events honoring the flier upon his return to New York. Novelty manufacturers turned out millions of Lindbergh dolls, buttons, flags, and other items to exploit America’s enthusiasm for its new hero. The “lindy” became the dance craze of the era.

Unprecedented triumph was followed just a few years later by unimaginable tragedy. In 1932, Lindbergh’s infant son Charles Jr. was kidnapped from the family home. A ransom of $50,000 was paid, but the child was never returned. The baby’s body was later found in the woods less than two miles from the Lindbergh home. Police arrested the kidnapper, Bruno Hauptmann, in 1933; three years later he was executed for his crime.

Shy by nature, Lindbergh found the glare of public attention uncomfortable, and moved his family to Europe to escape the constant harassment by the press. He devoted much of the remainder of his life to ecological and environmental issues. He also wrote a number of books; his autobiography became a phenomenal best-seller.

Charles Lindbergh died of cancer on August 26, 1974.

Basic Values

- Piloting combined his great loves of the outdoors, of adventure, and of mechanics

- Passionately anti-war; his efforts to influence his country to stay out of World War II provoked criticism

- A lover of nature and the environment; he served on the Citizen’s Advisory Committee on Environmental Quality under President Nixon

- Created a self-improvement chart on which he daily graded his own behavior in terms of “character factors” such as “altruism,” “tact,” and “unselfishness”

111

What the Naysayers Were Saying

- (From Harry Guggenheim, president of the Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics): This fellow Charles Lindbergh will never make it. He’s doomed.

- (From the editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, a paper considered a sponsor of the flight): To fly across the Atlantic Ocean with one pilot and a single-engine plane! We have our reputation to consider. We couldn’t possibly be associated with such a venture.

- (From the owner of a plane Lindbergh hoped to purchase): You understand that we cannot let just anybody pilot our airplane across the ocean.

The Darkest Hour

Though the murder of his infant son must represent the greatest ordeal Charles Lindbergh would ever have to endure, this tragedy took place after he had realized his dream as an aviator. But there were dark moments immediately prior to his historic flight as well. The press described pursuit of the Orteig prize as a “suicidal venture.” Lloyd’s of London was giving odds of ten to one against any successful transatlantic flights in 1927. Even more troubling were the fates of his rivals for the prize. Navy Commander Byrd’s monoplane crashed on its first test flight, injuring three crew members. Days later part of the landing gear on pilot Clarence Chamberlin’s plane tore loose during takeoff. Commander Noel Davis’s plane lost control during a trial flight, and both he and his copilot were killed.

Lindbergh retained confidence in his ability as a mechanic and a flier, and refused to allow the mishaps of others to diminish his determination to win the prize.

Validation and Vindication

- “No greater deed of personal prowess and adventure appears on the pages of man’s conquest of nature than this lonely and heroic flight.” —Dean Howard Chandler Robbins, Cathedral of St. John the Divine (New York City)

- Awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor

- Became the first recipient of Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” award in 1927

- Won the Pulitzer Prize in 1954 for his autobiography, The Spirit of St. Louis

112

Memorable Sayings

- “What kind of man would seek a life without daring?”

- “Whether outwardly or inwardly, whether in space or time, the farther we penetrate the unknown, the vaster and more marvelous it becomes.”

- “Is he alone who has courage on his right hand and faith on his left hand?”

- “Life [is] a culmination of the past, an awareness of the present, an indication of a future beyond knowledge, the quality that gives a touch of divinity to matter.”