You have to believe in yourself when no one else does. That’s what makes you a winner.

—VENUS WILLIAMS

9

Turning Support into Participation

We come now to the dreamcrafting macroskill supreme, the heavy artillery, the pièce de résistance that moves master dreamcrafters from the realm of the enthusiastic amateur into that of the polished professional at the top of his or her game. This is where a “darn good chance” of achieving the mission is transformed into a “can hardly miss” kind of proposition.

This, in short, is where inclusion comes to mean “participation.” It’s where others do more than support the dreamcrafter’s mission in principle—they invest time and energy of their own to help the dreamcrafter actually achieve the mission, because they have come to see it in some way as their own mission as well. Where once there might have been resisters blocking the way, there is now a cheering section prepared to help carry the dreamcrafter forward.

The fans in a sports stadium during season playoffs are doing more than “agreeing in principle” with their team’s attempt to win first place. They physically show up to shout their encouragement at the tops of their lungs; they wave their arms and dance and wear team-based colors and carry banners and placards of encouragement, and do whatever else they can think of to help spur their team on to victory. Does all this hullabaloo from the sidelines really make any kind of difference? Just ask the players why they believe the team playing before the hometown crowd always has the advantage. And for the fans, if their team wins, it’s very much their win; the dancing in the streets and whooping with joy might easily lead an intelligent observer from another world to assume it is the revelers themselves who have achieved something difficult and exhilarating.

What’s Leadership Got to Do with It?

During the entire sports season, prior to the playoffs, the fans follow their team’s progress daily in media sports coverage. If possible, they even follow the team in its travels to offer encouragement at out-of-town games. The team, in short, has a following.

171For there to be followership, there must be leadership. The team must do a great many conscious and deliberate things if it is to inspire in its followers loyalty and support at such a level.

It is this particular brand of inspirational leadership that master dreamcrafters learn to apply, albeit on a smaller scale, in the pursuit of their own mission. It is no accident that we feel inspired by fictional and real-life tales of heroism, by examples of individuals overcoming great obstacles to achieve their mission. Almost despite ourselves, we want them to succeed—because, among other things, it restores our belief that difficult objectives can be realized, that the individual can triumph, that perhaps an ambitious Big Dream of our own can similarly be achieved some day. It is this sense of connectedness that the expert dreamcrafter seeks to awaken in those around him or her, the sense that “at the very least, helping me achieve my dream will make you feel good about having contributed to something worthwhile, and at the most may inspire you to rekindle a sense of mission around your own Big Dream.”

John Scherer (at the Center For Work and Human Spirit, Spokane, Washington) describes all the visible interactions between society’s “roles” (between police officers and criminals, between teachers and students, between parents and children, and so on) as taking place “above the waterline,” in plain view of all. He suggests that beneath this role-based view that so dominates our interactions with others is the hidden dynamic of the police officer as the person behind the role, and how he or she relates to the criminal as the person behind the role, and so on. This is the less-visible exchange that takes place below the waterline, so to speak. It’s the element that connects with the “humanness of us all.”

This ability to operate below the waterline shows up, for example, in those adults who interact so effortlessly with younger children. Their success is primarily because they do not treat the youngsters as children (the “role” view) so much as simply “other people” with whom they quickly set about discovering all the things they have in common. This entirely natural, shared quest for common ground is an act of inclusion at the most basic level, and occurs spontaneously whenever strangers meet who are prepared to like each other. The more areas of common interest they uncover, the greater their affinity grows.

172Racism, sexism, ageism—all of the “isms” that connote bigotry or intolerance—are the product of interactions unfolding only above the waterline, a totally role-based view that excludes all those who are judged not to fit in or belong. When meeting strangers in roles different than their own, individuals limited to this view will typically be prepared to dislike each other. They will be inclined to make a negative prejudgment, the literal meaning of prejudice. Bigotry is just one more form of pessimism, even if it happens to be one of the ugliest. High society, cliques, the “in crowd,” the “popular set”—all of these are informal mechanisms of social exclusion. Those who cultivate a lifestyle of exclusion often don’t know when to stop. Even among the members of a clique, some seem to fit in less well than others. The inner core of the group continues to shrink, until it eventually reaches a nucleus of only two individuals. Even then, one of them just somehow doesn’t seem to be meeting the same high standard as the other, and the final act of exclusion leaves the self-appointed embodiment of perfection a virtual recluse, in near total isolation from all other people. No one else in existence quite measures up.

Leadership—the activity, not the role—is in its most fundamental sense an act of inclusion. It requires figuratively poking one’s head below the waterline in order to see beneath “roles,” and connect with “people.” Leadership in action conveys to one or more individuals, “I’m going someplace exciting and I’m inviting you to come along.” Inspirational leadership goes one better; its position becomes, “I need your help to get there.”

The leadership crisis in so many organizations stems in large part from a failure to distinguish between leadership as a role and as an activity. Many managers have assumed the role; few engage in the activity. The dominance of the role-based view is betrayed by the very language of organizational life: employees are not partners (which would connote inclusion), but rather subordinates (or worse, underlings) who report to superiors. And what could be more divisive than referring to other sections of the organization as divisions? The activity of leadership unfolds below the waterline, where people relate to other people as people.

173Effective leaders ignore roles, and connect

with the people beneath the roles.

Dreamcrafters begin exhibiting leadership the moment they engage in the process of declaration. Simply taking the time to articulate the mission, the vision, and the values represents a clear gesture of inclusion, an effort to let others in on the dream, and thus set the stage for them to begin painting themselves into the picture. Going beyond declaration to solicit support, as outlined in the previous chapter, raises the inclusion stakes by implying or stating outright, “It will be much more difficult for me to reach my destination unless you’re behind me on this thing.” The leadership component kicks in fully when the message becomes “Nothing would make me happier—and increase my chances of success more—than if you agreed to come along for the ride.”

A Formula for Taking the Lead

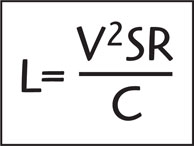

Inspirational leadership is not an impenetrably complex and abstract concept; in fact, the fundamentals can be boiled down to a reasonably simple bite-sized formula. The elements of this formula apply with equal relevance to political, social, and business leaders at all levels, and to individual dreamcrafters seeking to maximize the involvement of others in their mission.

174

In this formula, leadership (the “L factor”) increases as a function of our values times vision (V2) multiplied by our ability to signal these (S) and to respond appropriately (R) to challenge (C).

The formula brings together much of what this book has covered thus far, and brings it into focus as a mechanism for inspiring others to participate in making your dream a reality. It is, in other words, a way to summarize in shorthand the craft of turning support for any mission, big or small, personal or corporate, into active participation.

Thus, when you know where you’re going (that is, your mission and vision of success are clearly defined), and you know what you believe in (your values, too, are clearly defined), these powerful “ V factors” increase each other as through multiplication (rather than addition) to drive your L factor up. When, in addition, you signal your mission, vision, and values at every opportunity (in both word and deed, through the ongoing processes of declaration, measurement, celebration, and so on), a further multiplication occurs. And finally, when you respond to challenge in an appropriate manner (by taking care to avoid putting resisters on the defensive, for example, and by asking more than telling), the L factor increases once again.

Responding appropriately to challenge in this context means resisting the temptation to invoke the authority of roles (“Because I’m your parent, that’s why!”) and connecting instead to the person beneath the role. Instead of referring to titles or labels (that divide), or economic differences (that divide) or age differences (that divide), or educational differences (that divide), or any differences (that divide), the appropriate response is one that connects to the child-within-the-person at the basic human emotional level (that unites us all). Dreamcrafters who know and declare what they believe in must seek to understand what the resister believes in, and how these values translate into resistance to the dream. The dialogue can then bypass the divisive elements of role and label and build upon the common elements of deeply held values. By keeping personality out of the discussion, and by using an asking-rather-than-telling approach to find ways to resolve the apparent clash of values, it is often possible to turn even loud protestors into avid supporters.

175Indeed, in one of the great ironies that dreamcrafting brings to light, it is actually not at all uncommon for the most vocal resisters to wind up becoming among the most enthusiastic champions of a given mission. Strange but true. Every time a resister registers his or her total opposition to the dream, or engages in passionate debate about it or about something related to it, this individual is knowingly and deliberately keeping the dialogue alive, keeping the channels of communication open. It is as if he or she were saying, “I’m still not convinced, I doubt you’ll ever succeed in convincing me, but by all means give it another try.”

Virtually all the resistance and naysaying any dreamcrafter will ever encounter can be traced back to fear of one sort or another. Above the waterline is a noisy, boisterous protestor shouting resistance to the idea; submerged far below the waterline in many such exchanges is a frightened person very timidly calling out, “You know, I’d actually like to believe in this idea, but I’m afraid to, in case I’m later disappointed or it otherwise proves to have been a ghastly mistake. But let’s keep arguing about it, because maybe sooner or later you’ll succeed in putting some of my fears to rest—and even if you don’t, well, at least it makes for a lively discussion.”

Resistance can sap enough of a dreamcrafter’s time and energy to put the mission in jeopardy; but through skillful application of inclusion techniques, resistance can be turned into support and even participation. The high-energy resister, when converted, typically becomes a high-energy contributor. Time and energy invested in the macroskill of inclusion can pay huge dividends.

176In some situations, what passes for indifference can be a potentially greater threat to dreamcrafters than resistance. The individual who adopts a position of, “Oh, do whatever you like, just don’t bother me about it,” is formally closing off channels of communication. Techniques of inclusion are more difficult to apply to those who are working just as hard to keep themselves excluded. Truly impartial neutrality is rare in human affairs; those who profess indifference are sometimes (we stress, sometimes) individuals whose levels of fear extend to a fear of being persuaded that their fears are groundless. It’s not unheard of for the “indifferent” to later engage in subtle—and in extreme cases not-so-subtle—forms of sabotage to derail the dreamcrafter’s mission, all the while insisting they are totally indifferent to the whole matter. There comes a time in some dreamcrafters’ lives when it may become necessary to accept the fact that no amount of skill or effort is going to succeed in turning one or more individuals into supporters of the Big Dream, let alone participants in its realization. In such (fortunately rare) circumstances, the best course of action will sometimes be to rechannel these skills and efforts into other aspects of the mission, and hope that success itself will be enough to draw these individuals into a more supportive stance.

The ultimate object of inspirational leadership is to inspire others to voluntarily utter the magic question, “What can I do to help?” This magic question (or equivalent) represents one of the most powerful and visible manifestations of life coming into alignment that dreamcrafters can ever experience. It is as if the power of the magnetic field beneath the iron filings has increased; filings that at first resisted drifting into alignment suddenly snap into position, and the overall pattern becomes more unidirectional and pronounced than ever before.

But sometimes converted resisters won’t blurt out the magic question all at once; sometimes (perhaps as a face-saving mechanism) they will quietly progress through the entire range from resistance to support to participation in slow, barely perceptible increments (and even later imply that they’d been fully supportive and involved from the outset). Or sometimes they’ll say the magic question to themselves and quietly look for ways to help without drawing attention to the fact. In either case, from the dreamcrafter’s point of view, the skillful application of leadership principles has created a “following,” and has brought the aspirational field into significantly greater alignment.

177What remains is to get these eager-to-help supporters helping in one very special, particular way—one designed to expand the net of inclusion and turn other resisters into supporters as well.

Ambassadors at Large

Sports fans never seem to tire of the debate: which is the better team, and why? Movie buffs compare notes after a batch of new films appear at the local multiplex: which was the better film, and why? Which car dealer offers the best prices in town? Which television series had the best episode last night? Best pancakes around? Best vacation spot in the world? Best real estate agent? Best book on crafting your dreams?

In most such discussions, someone is making an effort to change someone else’s mind about something. In their enthusiasm for whatever it is they’re extolling, they have voluntarily appointed themselves a spokesperson for it. Without any financial compensation for their trouble, without even so much as the knowledge of whoever it is whose cause they’re defending, they’re prepared to make a personal effort to bring someone else into the fold—purely and solely because it’s something they like, something they believe in.

They do the work of professional goodwill ambassadors. They do it gladly, and they do it for free.

It’s one of the basic timeless truths of advertising: word of mouth is everything.You can invest millions to hype the latest Hollywood blockbuster prior to its opening weekend—but after that, it lives or dies by word-of-mouth. Whatever you’re selling, gotta get people saying good things about it.

178Master dreamcrafters recognize that in one way or another, they’re selling an idea to those around them. Maybe it’s, “This dream of mine is pretty interesting, and getting involved is going to make you feel good.” Or perhaps it’s, “If you help me get this going, that may be enough to inspire you to do something similar yourself.” Or maybe it’s nothing more than, “You know how difficult this will be for me, but I’d be very pleased if you simply followed my progress. I’m determined to make you proud of me.”

Whatever form it takes, if and when the dreamcrafter’s consistent use of the techniques of inclusion eventually inspires supporters to ask the magic question, an ideal answer to the question is one that meets these criteria:

- It would be easy (and preferably fun) for the supporter(s) to do

- It would create a genuine sense of contribution

- It would justify sharing some of the glory

Naturally it won’t always be a simple matter (or even possible) to involve others in ways that meet all of these criteria—but the closer the dreamcrafter can come to doing so, the greater the likelihood that these helpers will subsequently be inspired to voluntarily take on the role of goodwill-ambassador-at-large. Virtuosos of dreamcrafting apply the macroskill of Inclusion to create a situation in which others eventually come to be handling much of the battle against resistance, freeing the originator to focus his or her energies elsewhere.

Even the most private sorts of Big Dreams—losing weight, for example—still provide opportunities for others to get directly involved. One helper, for example, may be in charge of computing daily calorie counts, and making dietary recommendations to keep the totals within target limits; another may scour the Internet or the cookbook sections of libraries or bookstores in a constant search for new low-calorie recipes; yet another may enjoy actually preparing special desserts or other food items to support the diet. Naturally, in cases where the dream is more elaborate (build an extension to the house, launch a furniture business), the opportunities for involvement multiply. But in all cases, the dreamcrafter gives a gift to his or her future self by matching to each supporter a specific answer to the magic question that comes closest to meeting all three of the criteria listed above.

179Most powerful among these three criteria is the third. As harmful to the dreamcrafting cause as deflecting applause may be, hogging the applause can be even more so. Sharing the glory is the secret weapon that gives master dreamcrafters their greatest advantage.

The Sublime Paradox

People setting out to make a significant improvement in their lives (and sometimes in the lives of others as well) must learn to apply certain skills, which we have been referring to in these pages as macroskills. These skills have both practical and theoretical components; understanding the why is as important as the how. In some cases, however, the why element can be a little more difficult to grasp. At times, it can almost seem to defy common sense. In some cases, for some people, it can even require what amounts to nothing less than a blind leap of faith.

We touch, now, on what for some may prove to be such a case.

The expression “only in it for the money” is typically used to (derisively) refer to anyone who undertakes any sort of enterprise solely on the basis of what it will pay, in virtual disregard of all other factors (including even how personally distasteful it may be). The same society that sneers at those who do things purely for the money, however, tends to admire and respect those who have risen from humble beginnings to positions of wealth and privilege. This may be because our society is largely made up of individuals who at the instinctive level know something to be true that, when articulated at the level of logic and reason, seems to represent a paradox: those who are “only in it for the money” somehow tend to wind up with less money in the long run than those who are in it for the enjoyment, or sheer love of it. It is almost as if we have an unspoken understanding that many of those who became wealthy by their own doing may to some extent be worthy of admiration precisely because wealth was not their primary objective. They “followed their bliss,” as mythologist Joseph Campbell puts it, and the money ensued almost incidentally.

180This has long been one of life’s profound secrets, one that only a small portion of the population ever fully appreciates. Other secrets in a similar vein are no less paradoxical. Only a handful of leaders, for example, have come to understand that the most effective way to acquire power is to give power away. It’s those leaders who delegate authority along with responsibility who earn the deepest respect and loyalty of the people around them; it’s those who dare to demonstrate the highest levels of trust who are in turn most trusted.

And among dreamcrafters, those who amass the most glory for their achievements are typically those who, along the way, most readily passed the glory on to others around them.

A common thread running through all of these examples relates to our discussion (in chapter 7) of grabbers versus anticipators: the contrast between those in pursuit of instant gratification, who may often feel inclined to hoard, and those able to delay their gratification, who may be more inclined to share. The great lesson so few ever learn, the profound irony so few ever appreciate, the sublime paradox so few ever come to understand, is that those who share almost always wind up with much more than those who hoard. In describing Scrooge’s overnight transformation from hoarder to sharer in A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens paints a vivid picture of an individual who, from the very moment he learns to give, begins to receive—the sublime paradox illustrated in its purest form. It remains too great a leap of faith for many, of course; but stories and fables on this theme have endured through the centuries precisely because so many recognize (even if only unconsciously) that they remind us of a timeless truth.

181At the outset, the dreamcrafter’s objective is clear. But as early successes lead to recognition and celebration, the positive attention associated with these highly invigorating time-release motivators can become almost intoxicating, almost addictive. Unaccustomed dreamcrafters can sometimes be in danger of losing their focus. In a quiet and subtle way, the quest for more ego-enhancing recognition—more glory—can gradually begin to supersede the original mission objective. For the athletic runner, it’s that dangerous moment when the fame and fortune associated with winning a gold medal has come to seem a more appealing goal than perfecting the body’s ability to run with the greatest possible speed and efficiency. For the movie actor, it’s when the cheering fans at a film’s premiere provide a bigger kick than turning in an outstanding performance in front of the camera on a quiet soundstage.

This is dangerous because the sublime paradox still applies—only this time, it’s a question of those who are only in it for the glory potentially winding up with less glory than if they were instead still in it for the sheer love of it. The power of any aspirational field derives from its focus on a single clearly defined objective. If a second objective is brought into play, it creates interference; the concentration of energy is diffused, the alignment element weakened, the overall likelihood of success diminished. The new Mission B (to maximize the personal glory associated with achieving Mission A) reduces the chances of ever achieving Mission A, and thus of ever savoring the glory associated with it.

Mildred has an ambitious two-year dream—to transform her spacious front yard into a beautifully landscaped “enchanted garden” with flowers lining a winding stone walkway beneath the leafy trees, and even a little pond with a fountain next to an old-fashioned park bench. As she works on this ambitious project, neighbors begin to take note and offer encouragement. One of the neighbors works at the local newspaper, and arranges to interview Mildred and take photos of the progress being made. After the story appears in the newspaper, people from across town begin driving past, and even stop to ask Mildred questions or offer further encouragement. Her children, impressed with her sudden semicelebrity status, seem to look at her in a new and more favorable light—and Mildred herself finds all the attention extremely gratifying. She is astonished to receive a phone call from a producer at the Home Improvement Channel, who saw the newspaper story and would like to do a television feature on her project within a week or so.

182Mildred’s head is spinning with excitement. She immediately begins thinking at length about the kind of clothes she should buy for the interview segments of the show and the kind of hairstyle that would be most appropriate. For the first time since work on the garden was begun, the wheelbarrow and other tools sit idly in the storage shed and the garden remains untouched over several days as Mildred scurries from shoe stores to tanning salons to hair stylists.

Just days before the television crew is scheduled to arrive, Mildred receives a call from the producer advising that they have found a similar project closer to their production center, and for economic reasons will instead be featuring the alternate project on their program.

At first Mildred is deeply disappointed—but then she reminds herself that the Home Improvement Channel is not the only purveyor of such programming. She begins a months-long letter-writing campaign, sending copies of the newspaper clipping (along with additional photos taken by a local professional photographer) to producers of gardening and do-it-yourself shows across the country. But the results of her mailing campaign are disappointing. Even the local television stations express little interest.

The unfinished garden itself, meanwhile, is beginning to show signs of neglect. When Mildred looks at it through her window, she finds it more difficult to summon up the kind of enthusiasm for the project she once had.

A new, second mission became the focus of her attention, and this weakened her resolve to achieve the first. A single aspirational field creates alignment; introduce a second field along a conflicting axis and alignment is reduced, and potentially even negated. The conflicting fields can cancel each other out.

183

Protecting the Aspirational Field

Does all of the foregoing not create a contradiction with some of what came before? In our (chapter 5) examination of time-release motivators, did we not stress the beneficial effects of recognition and celebration as motivational reenergizers? There, personal glory was good, so why should it be bad here?

The distinction may seem extremely subtle, but it is also extremely important. (Remember, we’re now discussing a technique used by master dreamcrafters. As the sophistication of the techniques increases, so must the sophistication of the thinking behind them if they are to be used effectively.) In this context, “good” personal glory supports the Big Dream mission objective by intensifying resolve within the dreamcrafter or within others; the “bad” variety is any that makes the subtle shift from being a motivational tool to becoming a secondary mission objective in its own right.

Or, to put it another way, though personal recognition and celebration are always extremely rewarding, they must never be allowed to become actual rewards in the literal meaning of the word. Mildred fell victim to the “reward trap” described in chapter 5; she allowed her minicelebrity status to become in her mind an extrinsic reward for the work she had done in her garden. Such extrinsic rewards tend to devalue the very thing they are rewarding; the garden became less important to her than advancing the cause of her celebrity. With a deeper understanding of the Motivation macroskill, she might instead have put all of that personally rewarding recognition to work for her as a motivational tool, to intensify and sustain her determination to complete the garden— not to drum up more recognition for herself. (Who knows what kind of recognition might have come her way if she’d seen her garden through to completion?) With a better grasp of the Inclusion macroskill, she might have chosen to share the recognition with those around her, to inspire and motivate them to help her make her dream garden an even more magnificent reality.

184There is no “bad” personal glory for dreamcrafters; there is only personal glory put to bad use. Note that those who are not “only in it for the money” do not as a rule object when money materializes; indeed, their swelling bank accounts become a source of great personal satisfaction, of vindication, of motivation to keep the original Big Dream alive and in focus. Similarly, those dreamcrafters who resist allowing themselves to be “only in it for the glory” are not unhappy when personal glory comes their way; to the contrary, they recognize its power to help propel them closer to their dream.

This is a book about bringing life into alignment. The aspirational field is the primary mechanism for doing so. Powerful as they can be, aspirational fields do retain one critical vulnerability: they can easily be weakened or canceled out altogether by interference from a conflicting field—that is, by any secondary mission that might compete for attention, time, energy, and so on. It is up to the individual dreamcrafter to protect his or her aspirational field from such interference by keeping all potential secondary missions out of the equation. Precisely because of its great power as a time-release motivator, however, personal recognition becomes a double-edged sword, potentially seducing the dreamcrafter into its further pursuit as a new, secondary mission in its own right. This is the challenge that to one extent or another confronts virtually all dreamcrafters—how to retain the full motivational power of such recognition while at the same time protecting the aspirational field by eliminating the danger of a secondary mission evolving around the pursuit of more of the same for its own sake.

The most effective way—indeed, perhaps the only way—to overcome this challenge is to spread the glory around. Redirect every compliment (“Oh, thank you, although that was actually Gerry’s idea, and it’s a real beauty”). Reassign every commendation (“I must tell you, that part is something I could never have done without Lou’s help”). At celebrations of success, ensure that the entire support team is included in photos. Wherever and whenever possible, at every conceivable opportunity, make your successes look, sound, and feel less like a solo achievement and more like a dual or team or group effort. The hallmark of the master dreamcrafter is to always resist hoarding the glory, always favor sharing it.

185Not one, not two, but three important benefits derive from this one simple but powerful principle:

- It protects the aspirational field. While group recognition retains virtually all of its motivational power for the group leader, it nevertheless loses a great deal of its seductively personal quality, and thus becomes far less likely to take on a life of its own as a secondary mission.

- It motivates others to turn their support into participation. This is the crux of the matter; there can be no more persuasive way to make others feel your dream is their dream than to present it as their doing as much as your own, and to allow them to bask in the glory accordingly. One especially valuable by-product of such participation is its tendency to create goodwill ambassadors for the dream.

- It generates more glory in the long run. This is where the sublime paradox comes into play; motivate others (by sharing the glory) to help you achieve your dream, and a level of success that would not and could not have been achieved without their help leads to recognition and celebration far beyond anything you might have enjoyed on your own.

The dreamcrafter’s secret weapon: share the glory.

It is the ability to inspire others to participate in the Big Dream that sets master dreamcrafters apart, and helps bring even “impossible dreams” to life. Among all the advantages that derive from this particular macroskill, there remains one with especially profound implications, one we have touched on only lightly up to this point.

It is not uncommon for those who are allowed to observe firsthand (through direct involvement) how a dreamcrafter makes his or her dream a reality to feel inspired to emulate this example and set about making some cherished dream of their own come true as well. The dreamcrafter’s optimism is contagious, and the macroskills themselves can be learned as readily—if not more readily—through observing a good example of their application at close range as through reading a book about them.

186Success inspires others to strive for success. Part of what dreamcrafters leave behind them, even after they are no longer around to enjoy the fruits of their personal dream realized, is the ripple effect of their example on two, or twenty, or a thousand other people. It’s a gift all dreamcrafters give to everyone else—a restored belief that dreams really can come true.

Is this an important gift to pass on? We would not be here right now, living in a society where we can engage in a leisurely discussion of such questions, if those who built the society for us had not first been inspired to believe it could be done—inspired by the examples of others who had come before, and who in turn had shown that dreams can be made real.

Now it’s our turn to show the way. Now it’s our turn to lead the way. That’s what leadership’s got to do with it.

GALLERY OF DREAMCRAFTERS

THE WILLIAMS SISTERS:

VENUS (1980- )

AND SERENA (1981- )

The Big Dream

For the Williams sisters the dream of tennis stardom began even before they were born. In 1978, their father Richard watched on television as Virginia Ruzici won the French Open women’s singles championship. Impressed with the total amount of her winnings, he vowed that any future children of his would take up tennis. His daughter Venus was born two years later, and Serena followed just over a year after that.

Although Richard had never played tennis himself, he brought four-year-old Venus to public tennis courts in the Watts and Compton areas near Los Angeles, and appointed himself her coach and trainer. A year or so later, Serena became part of the outings.

At age nine, despite showing promise as a runner, Venus decided to make tennis the focus of her young life. She was the subject of a 1990 New York Times feature that bore the headline, Status: Undefeated. Future: Rosy. Age: 10. In 1991, Richard moved the family to Florida and enrolled the girls in a tennis academy with a practice schedule of six hours a day, six days a week. Richard predicted that one day both of his daughters would occupy the top two positions in the world.

By 1994 Venus had won her first professional match; four years later she teamed with her sister to win the pair’s first women’s doubles title. After defeating Anna Kournikova in the 1998 finals of the Lipton Championships, she reached the top ten (at age seventeen). In 1999, in the first contest between sisters in a professional women’s final since 1884, Venus beat Serena at the Lipton Championships, bringing Serena’s sixteen-match winning streak to an end. The sisters went on to beat Martina Hingis and Kournikova at the French Open, to become the first sisters to win a doubles title in the twentieth century.

188In July 2000, the sisters were named to represent the United States at the Summer Olympic Games in Sydney. Venus won the gold medal, and in so doing became only the second player (after Steffi Graf) to win Wimbledon, the U.S. Open, and the Olympics in the same year.

In a striking demonstration of positive expectations, Venus arrived at Wimbledon wearing a sleeveless gown in anticipation of the champion’s dinner. “I had to make myself a promise,” she later explained, “so I bought the dress.” She wore it at the dinner after winning, as planned.

Venus and Serena Williams fulfilled their dream of becoming ranked the number one and two females in professional tennis in June of 2002, and made a frequent point of sharing the glory with their father. “It wasn’t like I was self-motivated,” Venus told one interviewer. “My dad started me. It was his dream before it was mine.”

Basic Values

- Believe in yourself

- Learn from your mistakes

- Use your time wisely

- Take good care of your body

What the Naysayers Were Saying

- The media ridiculed their appearance (the braids and beads), their behavior, their attitude, their upbringing.

- Their father predetermines the outcome of their matches against each other.

- Their climb was made easier because Hingis and [Lindsey] Davenport were out with injuries.

- They are helped by being black. Endorsers seek them out for that reason.

The Darkest Hour

In March 2001, at the Tennis Masters Series in Indian Wells, California, Venus withdrew from a semifinal match against her sister when the ten-donitis in her right knee became too painful. The crowd began booing in what several commentators described as “lynch mob” fashion. Rumors of a conspiracy to “fix” matches in which the sisters play against each other were rife, despite being dismissed by tennis officials as unfounded. Even after Serena’s win, the hysterical racism of the crowd filled her ears. Richard later told the press that one man in the crowd threatened to “skin him alive.”

189“It could never, ever get worse,” Serena said, recalling the event.

Richard insists that the criticism he and his family have received has served to bring them closer together. “A person can pick at you so long,” he says, “enough that, instead of making you weak, it makes you strong.”

Validation and Vindication

- In 2000, Venus became the first women’s tennis player to win Olympic gold in singles and doubles since 1924.

- Venus was named Sportswoman Of The Year by Sports Illustrated in 2002.

- Venus earned her second gold medal in 2000 as the sisters defeated Miriam Oremans and Kristie Boogert 6-1, 6-1 in the most one-sided final in Olympic tennis history.

- The Williams sisters earned the number one and two rank in 2002.

Memorable Sayings

- (Venus): “You have to have goals for yourself.”

- (Serena): “Whatever my potential is, I want to reach it.”

- (Venus): “You try not to limit yourself on what you can do.”

- (Serena): “Just have fun. Whatever you do, have fun, enjoy it, and work really hard.”