Chapter 28. Achieving Best Fit

Judith M. Bardwick, Ph.D.

At the dawn of the 21st century, we find a much broader range of organizational characteristics, a wider range of people's attributes, and a greater insistence on individuality than we have seen before. As a result, the tasks of management in the 21st century will be much more complicated and customized than they were in the 20th.

While many fundamental economic conditions are changing, they are changing at different rates in different places and in different industries. The result is a range of basic economic circumstances. Because of the diversity of fundamental conditions, there is also a broad range of basic practices, values, and expectations among different organizations. This broadened range of economic and institutional conditions increases the importance of another change: There is a far broader range in people's key motives and personal characteristics than we've seen in the past.

The people issues of the 21st century are more complicated than they were in the 20th century, when virtually every person and every organization were fundamentally alike. In the 21st century, management must pay far more attention to individuals. The core differences between individuals will require that organizations customize many practices in order to engage, satisfy, and motivate people. Management now needs great listening skills, because they must relate to and lead people whose views and priorities are different from their own.

Because of the widened range of attributes of organizations and of people, the key to success in the 21st century is achieving a best fit between the priorities and characteristics of the people who are invited to join an organization and those of the institution.

Stable and Borderless

The earth's tectonic plates are shifting; economies, governments, and social values are changing. Extraordinary advances in technology, especially, have created a worldwide economy, and that has created the conditions of permanent turbulence that I call borderless. Increasing numbers of organizations and people, everywhere, face ever-increasing competition and accelerating change.

There are, though, still some nations, industries, and organizations that remain largely on a stable path; in other words, they change slowly, they offer some level of job security, and they honor seniority. Universities, unionized organizations, many governments, civil service, and the core business of utilities come to mind.

A second group of organizations, which includes the majority of large and mature businesses, have found it necessary to transform themselves over roughly the past 15 years. They've had to change from the calm, slow-moving gait of stability to something significantly faster, flexible, and friskier. Those organizations have been striving for and achieving some fundamental changes in their culture, strategies, and practices. Total change is so difficult that a total transformation is exceedingly rare. That's why organizations that set out on the path of transformation generally continue on that path permanently.

The third and smallest group of organizations was founded in the past 20 years and especially in the 1990s. Since these companies were established in borderless conditions, they take ever-increasing requirements for innovation, adaptability, and speed for granted.

While it's always been true that different people have different priorities, today we have far greater differences in priorities between people than we ever had before. The e-conomy or borderless conditions have greatly broadened both the conditions of work and the possible payoffs of work. The largest differences are between stable and borderless organizations and the people who are attracted to one or the other of them.

There are three basic kinds of organizations: stable, transitional, and borderless. People can also be clustered into the same three groups.

Just a decade or two ago, virtually every employee in every organization was a stable employee: a person whose key goal was first to achieve security and then to achieve some reasonable level of success and a comfortable and predictable life. Stable people are still the largest, but they're not the most important group in the population.

Depression-impacted, stable people are security seekers. While the great majority are far too young to have lived through the Great Depression, they learned the lesson of putting security first from their parents or grandparents...or they saw the local factory closed, putting a town out of work...or they were let go and discovered their skills had little value.

Because all security seekers are Depression-impacted and share the fear of financial disaster, people in this group are far more alike than they are individuals. In the 20th century, when achieving security was the core goal for almost everyone, organizations were able to effectively deal with stable people as members of a group. Operationally, this meant that fairness was defined as identical treatment and outcomes for everyone. It meant that identical compensation and lock-step promotions were "fair," and those outcomes that reflected individual merit and contributions were "unfair."

A second, small but important group of people has emerged, that of the borderless warriors. These people are fundamentally different from stable security seekers. They thrive on risk, change, and unpredictability; they see more opportunity than threat in those conditions.

Borderless warriors are the first group of people since the Great Depression who bear no Depression scars. They've lived through bad economic times as well as good, and their innate optimism is tempered by a strong sense of reality. Honed by hard times during which they still achieved success, these people are genuinely confident. Borderless warriors are not deterred by lay-offs and the demise of the dotcoms; they find these times exciting and fun.

This small group is disproportionately important, because these people are the natural leaders in borderless organizations. Wherever conditions require that things be done significantly better, faster, and cheaper, these people need to be at the helm. People who prefer borderless conditions are far more likely to succeed during these times, because they inspire confidence and hope in the organization's people who are not borderless warriors.

The third group of people is the most difficult cluster to understand and motivate. They look and talk like borderless warriors, but while a few become courageous and entrepreneurial, the great majority do not develop the required confidence and personal strength.

This group is made up of two subgroups: One cluster includes young people, especially fairly recent college graduates, who have no memory of the last severe recession, which occurred in 1981–1982, and who have never seen a prolonged bear market. Growing up during two decades of good times, even after the stock market tumbled in 2000 and the economy stumbled into very slow growth, this group continues to say they expect to achieve major success, within—at the most—5 years. But their confidence and optimism are illusory. Without the experience of hard times, courage and tenacity are untested and therefore undeveloped. We can't know what this group's long-term attitudes and expectations will be, because they will be largely dependent upon what happens in the economy during the next 5 or so years.

The other people in this third group initially chose stable careers. They joined General Motors, IBM, or 3M, or they became accountants or lawyers. These people moved to borderless companies in the second half of the 1990s, either because the potential rewards were so breathtaking and/or because their self-esteem required that they join borderless startups to assure themselves that they, too, had what it took to be a borderless warrior.

When the bubble burst and the good times ended, the great majority of these people went back to the kinds of organizations and careers they had originally selected.

We might call the third group transitional: people who want to be borderless warriors and aren't; young people who are still in the process of developing strengths and confidence; and the very small number of stable people who discover that borderless conditions are exhilarating.

Best Fit

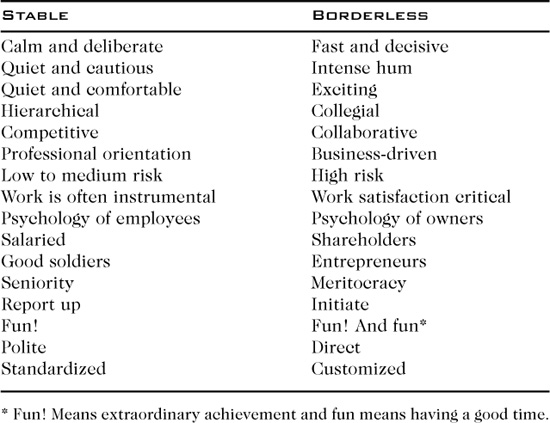

Borderless and stable organizations (see Table 28.1) are very different in terms of the experiences they offer, their priorities and values, the amount of compensation people might earn, their levels of risk or job security, and the opportunities they offer for making a difference: creativity and leadership. People who flourish in borderless organizations are very different from those who succeed in stable organizations.

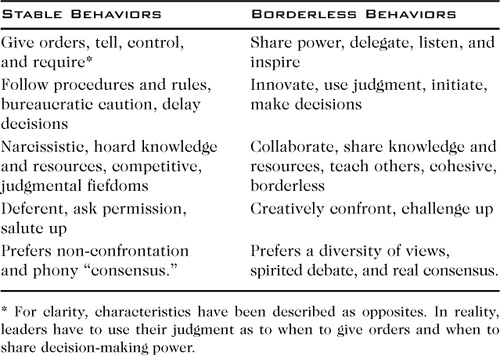

Different behaviors are required in different times, and many behaviors that are common in stable times are barriers to success in borderless times when fast, effective innovation is critical (see Table 28.2). In stable times, for example, leaders are expected to demonstrate authority by issuing orders, and subordinates are expected to do what they're told and keep on saluting. That's both slow and a waste of subordinate's knowledge. Even worse, that style precludes innovation.

Table 28.1. Characteristics of Stable and Borderless Organizations

Table 28.2. Stable Behaviors and Borderless Behaviors

There are two very different populations: While some people love unpredictability, risk, and autonomy, other people like to know their place and get their orders. One group perceives itself as Ferraris and the other group is content to be Fords. People who prefer to be in stable organizations prefer merry-go-rounds. Those in borderless organizations choose roller coasters.

The greater range of organizational conditions and the newly desired behaviors that are critical to the success of borderless organizations means there are no longer "best companies" or "best practices." There's no longer one size that fits all. Instead, there's best fit—a match between an individual's values, priorities, and behaviors and those of an organization.

Organizations in the 21st century will succeed by achieving best fit. They will select people who have the personal characteristics that are likely to result in their being successful within the organization as it is or will be, and whose most important needs and desires can be met. Ideal outcomes are achieved when there is a best fit between the requirements and opportunities of the organization and the capacities and priorities of the employee.

Best fit, compatibility between what the organization requires and what the employee desires, leads to high motivation, comfort, and success. A bad fit leads to discomfort, high stress, and failure. Without best fit, the chances for success and retention plummet; with best fit, the chances for success soar.