CHAPTER 7

The Collaboration: Storytelling and Story Tending

To touch the soul of another human being is to walk on holy ground.

—Steven Covey

Storytelling

Now that you understand the power of story and have built some stories of your own, it’s time to start putting them to use in a collaborative, reciprocal way—in real sales situations. Keep in mind that your stories are merely a means to an end, a way of helping your buyer to progress through his or her buy cycle. Ultimately, the goal is to influence your buyer to believe what you believe, to get to the top rung of the story ladder, to say yes.

The Language of Emotion

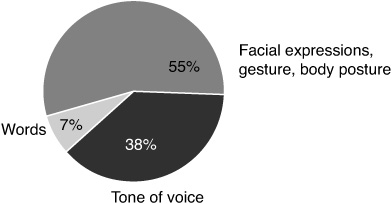

The first thing to understand about storytelling is that it’s not just what you say but how you say it. In fact, it’s mostly how you say it. People tend to think of spoken language as our primary means of communication, but studies suggest that words alone make up only 7 percent of human communication. The other 93 percent consists of tone of voice (38 percent) and nonverbal cues (55 percent) such as facial expressions, gestures, and body posture (see Figure 7.1).

Source: Based on Active Listening by Carl Rogers and Richard Farson

Most researchers now agree that spoken words are used primarily to convey information, via the left brain, whereas our other means of communication (body language, tone of voice, and facial expressions) are used primarily to convey feelings and emotions, via the right brain. “Body language is an outward reflection of a person’s emotional condition,” write Allan and Barbara Pease in The Definitive Book of Body Language. “Each gesture or movement can be a valuable key to an emotion a person may be feeling at the time.”

Therefore, if we’re going to activate a buyer’s limbic brain—his operating system, the part of the brain that decides to trust, to act, to take a leap of faith and try something new, to buy—then we need to be mindful of what Malcolm Gladwell calls “the persuasive implications of nonverbal cues” in his discussion of how the best salespeople influence others in his book The Tipping Point.

The system of cognitive transmission from mind to body is far more evolved than from mind to mouth. Long before humans developed spoken language, we were communicating with our bodies. Body language is also how we first begin communicating as infants. An 18-month-old shakes her head back and forth when she’s had enough peas, hugs a teddy bear that makes her happy, waves her hands when she’s excited.

Studies show that the signals sent by the limbic system to the body are much quicker and more reliable than the transmissions of our left-brain language center. In other words, the body goes first, and the body doesn’t lie. Before a five-year-old fibs about raiding the cookie jar, he’ll instinctively cover his mouth with his hand. When we feel threatened or defensive, we cross our arms. When we feel shame or embarrassment, we look away. When we feel pride, our chest rises and expands. Emotions such as boredom, excitement, fear, and arousal are readily conveyed by our facial expressions—often whether we want to convey them or not.

When the messages we send are incongruent—when our words don’t match our body language—a listener will tend to tune out the words and subconsciously focus on nonverbal cues. For instance, when someone asks how we’re doing and we say, “Fine,” the way we say it reveals a lot more than the word itself. In fact, your tone of voice and nonverbal cues can even tell a listener the exact opposite of what your words are saying. Even when we try very hard to deceive someone, our bodies are likely to give us away. Think of a poker “tell,” the unconscious physical gesture that tips off one player to the fact that another player is bluffing.

The power of nonverbal communication is well understood by actors. Silent-film audiences didn’t need words to know when Charlie Chaplin was feeling downtrodden and dejected, or when Buster Keaton was determined to succeed. Even with today’s movies, you can easily follow the emotional trajectory of the story with the sound turned off.

Nonverbal cues are critical even for orators and singers, people whose performances we strongly associate with the words. Look, for instance, at the lyrics to your favorite pop song. Chances are they don’t exactly qualify as poetry. But put them into the mouth of a gifted singer, and suddenly, shallow, simplistic lyrics can become moving, even profound. The effect can be even more dramatic in a live performance, where the singer’s body language and facial expressions come into play. Or watch a Martin Luther King, Jr. speech with the sound turned off—no words or tone of voice—and you’ll still get a strong sense of his power as a speaker and the emotion he wants to convey. It’s all in the delivery, using nonverbal communication to put emotion behind words.

Communicating the Emotion of Your Story

The left brain, where the language center resides, specializes in picking up and sending verbal messages. The right brain specializes in interpreting and sending nonverbal messages. Effective storytelling involves integrating the two sides of the brain, using both the verbal and nonverbal languages of emotion. The result is collaborative communication. Our brains are wired to connect with another person when feelings are expressed. The greater the feeling, the stronger the connection.

As Dr. Daniel J. Siegel writes in Parenting from the Inside Out:

When the primary emotions of two minds are connected, a state of alignment is created in which the two individuals experience a sense of joining. The music of our mind, our primary emotions, becomes intimately influenced by the mind of the other person as we connect with their primary emotional states. . . . Resonance occurs when we align our states, our primary emotions, through the sharing of nonverbal signals. . . . When relationships include resonance, there can be a tremendously invigorating sense of joining. (pp. 64–65)

Emotion is contagious. If we want someone else to feel what we’re feeling—if we want to trigger their mirror neurons, the basis for reciprocal conversation and reciprocal sharing of emotions—then we need to communicate our emotions through our body language as well as our words.

“Mirror neurons may also link the perception of emotional expressions to the creation of those states inside the observer,” writes Siegel. “In this way, when we perceive another’s emotions, automatically, unconsciously, that state is created inside us.” We may therefore experience fear when we see someone else in a state of fear, we may be inclined to laugh when someone else laughs, and so forth.

The storyboards you built in the last chapter are, quite literally, nothing but words on paper. It’s true that you need good stories, and it’s true that you need the right story for the job, depending on your selling situation and the rung of the story ladder you’re on. But that’s not enough. When it comes time to actually tell your stories, to communicate them to another human being, remember that those words on the index cards account for only 7 percent of the information you’ll be conveying. The other 93 percent will come from how you tell the story, using your tone of voice, facial expressions, and nonverbal cues.

So how do you tell a story with real emotion? Research indicates that our bodies will convey an emotion if we “check in” and become aware of that emotion. That’s one of the reasons we ask you to write, at the bottom of each index card, words that represent the emotions associated with each part of the story.

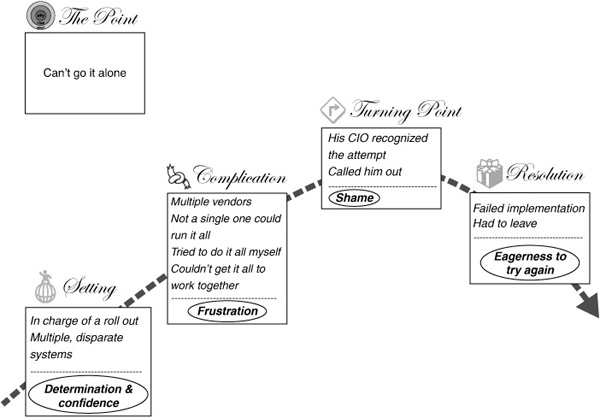

Remember Adam’s “Right Tool for the Job” story from Chapter 6 about the dangers of going it alone instead of asking for help? His storyboard is shown again in Figure 7.2.

Chances are, when Adam told his story, he used the words at the bottom of each card to describe the emotion he was feeling at each point in the story: “Back then I had a lot of determination and confidence. I felt like I could do it all. . . . When I wasn’t able to integrate the systems, frustration set in. . . . After my CIO called me out, I was full of shame. . . . I learned my lesson after the fact, and I was eager to try again.”

But Adam didn’t have to use the words. In fact, he could have told the story without using the actual words at all, and if he told it well, emoting fully, the buyer still would have known exactly how he felt throughout the story.

When you tell your stories, be sure to “check in” with your emotion words. Doing so will help you avoid monotone or tone-deaf storytelling. Just seeing the words on paper (or thinking about them when you’re telling a story from memory) will trigger cognitive transmissions that activate the right brain. Since the right brain is kinesthetically connected to the rest of the body, those transmissions will make it easier for you to emote. It’s that simple: by being aware of and attuned to the emotions, you can communicate them more fully. Your tone of voice, speech rhythms, facial expressions, and body language will reflect the emotion you’re recalling. This is storytelling from the inside out, starting with the emotion, not the words. It is a natural, intrinsic process. You might even try acting out parts of your story. Jump in and relive particularly vivid moments. The listener will jump in with you.

Ben’s Story: Bill Clinton’s Reality Distortion Field

I remember watching with a friend one of the 1992 U.S. presidential debates. It was George H. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Ross Perot in a town hall format, with an audience of ordinary Americans asking the questions. About halfway through the debate, the moderator took a question from a young African American woman in the third row.

“How has the national debt personally affected each of your lives?” she asked.

It was President Bush’s turn to answer first. My friend elbowed me. “Did you see that?” he said. “Bush just lost the election.”

“What are you talking about?”

“While she was asking the question, he looked at his watch.”

Sure enough, the gaffe received a lot of attention after the debate, but it was only the beginning of Bush’s mistakes.

“Well,” Bush said. “I think the national debt affects everybody—”

“No,” the woman interrupted. “How has it affected you personally?”

Bush looked stumped. After fumbling through an answer that devolved into an analysis of the semantics of the question itself, he took his seat. Bill Clinton followed with what struck me as a much stronger answer, and I came away from the debate feeling that he’d won.

Years later, once I started to learn about the importance of nonverbal communication, I came across what has become a widespread description of Bill Clinton’s charisma: “He makes you feel like you’re the only person in the room.” Commentators have dubbed it Clinton’s “reality distortion field.” That got me thinking about that 1992 debate, so I found the clip online to see if I remembered it correctly.

Sure enough, Bush’s answer seemed stiff, incoherent, cold. And sure enough, Clinton’s answer was more sympathetic and direct. But it wasn’t the difference in the candidates’ answers that struck me; it was the difference in their body language.

I watched the clip several times with the sound off. When Bush rises to answer the question, he hikes his pants like a cowboy facing a bull but takes only a step or two from his chair—like a nervous cowboy. When Clinton rises to answer the question, he immediately crosses the stage and stands near the front row, as close to the woman as he can get. As Bush answers the question, he takes another step forward but tucks a hand in his pocket. His facial expression is almost angry. He repeatedly turns away from the woman to address the rest of the audience. When he manages to look her in the eye, he wags his finger as if he’s scolding her. Clinton, on the other hand, speaks directly to the woman as if she’s the only person in the audience. His facial expression is sincere and compassionate. His hand gestures—touching his chest with both hands—convey inclusion and warmth. During Clinton’s answer, the look on the woman’s face makes it clear which candidate connected with her. And the look on Bush’s face—mouth open, stunned—makes it clear that he knows he’s out of his league.

That four-minute debate clip taught me everything I needed to know about the value of body language and eye contact, the way nonverbal cues contribute to that intangible quality known as charisma. It wasn’t about what Clinton said; it was all about how he said it.

Metaphors Shine in the Storyteller’s Toolbox

While the actual words you use to tell your story may make up only 7 percent of what you convey to a listener, you still want those words to count. One way to make your language more vivid and full of emotion is through the use of figures of speech such as metaphors.

A metaphor is a comparison that shows how two things that are not alike in most ways are actually similar in a significant way. For instance, the title of this section employs a metaphor, likening figures of speech to tools in a toolbox. You could also think of them as weapons in an arsenal, cards in a deck, and so forth—you get the idea.

A metaphor expresses the unfamiliar or abstract (the tenor) in terms of the familiar and concrete (the vehicle). When Pat Benatar sings “love is a battlefield,” battlefield is the vehicle for love, the tenor. Some common types of metaphors include allegories, parables, and similes. A simile is simply a metaphor that uses the word like: she runs like the wind, he drinks like a fish, and so on.

Metaphors are particularly useful for expressing intangible feelings and emotions. Let’s say you’re telling a story that involves a major deadline at work. You might describe the deadline as a noose around your neck, getting tighter every day. Or maybe it’s more like a dark cloud, a black hole, the edge of a cliff, an eighteen-wheeler bearing down on you, or a gun to your head. The range of possibilities is limited only by your imagination.

The power of metaphor lies in its ability to create a visual image in the listener’s mind. When a listener has to struggle to interpret or clarify an idea, the skeptical left brain is activated. Metaphors can make your story more colorful and reduce your listener’s mental “heavy lifting,” keeping him or her in a more receptive right-brain mode.

Getting Started and Passing the Torch

There will be sales situations when you can just launch right into a story as part of the natural flow of conversation. That’s how John Scanlon, the CEO whose story is in Chapter 1, did it: “Hey guys, that reminds me of a time when I was at MCI. . . .”

In other situations, you might need to shift conversational gears in order to start your story. There’s always the simple, straightforward approach: “Can I tell you a story?” Or maybe your selling situation will allow for a more specific transition: “Mind if I share a story about another CIO?” or, “Can I tell you a story about a client of mine who was facing similar challenges?”

In any case, these are all versions of that age-old story beginning “once upon a time.” Don’t underestimate its power. In our experience, people simply don’t say no to the offer of a story. For starters, it would be hard to do so without coming off as rude. More important, the promise of a story has a powerful subconscious effect, relaxing the left brain’s defenses and heightening the right brain’s receptivity. When we hear “once upon a time,” we subconsciously tell ourselves, “Oh, it’s just a story. I don’t have to do anything or decide anything. I can just listen and enjoy.” But at the same time we’re relaxing into the story, we also focus and pay attention, because we are story learners, biologically wired to learn through narrative. And so, paradoxically, at the same time our subconscious is saying, “It’s just a story,” it’s also saying, “I’d better pay attention; I might learn something.” This, as discussed in Chapter 5, is the power of story.

Meet Them on the Left Side

Most buyers are clutching their wallets when they first meet a salesperson. Their left-brain defenses are on high alert. Before a seller tries to connect with a buyer’s right brain, it’s a good idea to meet the buyer where they are—satisfy the left-brain first. We recommend beginning sales calls by offering a quick agenda, telling the buyer what your plan is: “What I’d like to do today is start by sharing my story with you. I’m interested in hearing yours too, and then we can decide where to go from there. Sound good?” Offering an agenda can quickly satisfy the buyer’s left-brain appetite to know what’s going on, which then opens the door for the seller to shift over and begin activating the buyer’s right brain with a story.

Of course, there’s no one right way to start a sales call. And sometimes it’s the buyer, not the seller, who begins the conversation. In those cases, instead of telling a story right off the bat, the seller has an opportunity to begin by tending the buyer’s story—a process described later in this chapter.

How Long Should My Story Be?

The length of a story is an important consideration. You want a story to be long enough—that is, developed enough— that it effectively makes its point. But you don’t want it to be so long that the listener begins to feel bored or impatient. Ultimately, the ideal length depends on the story itself. Mark Hurd’s story about his daughter, presented at the beginning of Chapter 4, lasted barely two minutes—but in that short time, he managed to transform the room.

The ideal length also depends on how much time you have and on your listener’s reaction. If you sense that your listener’s attention span is nearing its end, wrap up the story quickly. If your listener looks like he hopes you never stop, milk the story for all it’s worth.

It’s a good idea to have a mix of shorter and longer stories in your repertoire—30 seconds, 3 minutes, even 10 minutes if, for example, you’re making a presentation using visuals. In fact, it’s also a good idea to practice shorter and longer versions for each of your stories.

In our experience, a story for a first sales call should take not more than three minutes to deliver effectively. You want to begin establishing an emotional connection with your buyer through story as soon as possible; at the same time, however, you don’t want your buyer to feel buttonholed before you’ve even gotten a chance to know each other.

We’ll take up the issue of story length again in Chapter 10 when we get into the tactical use of different stories—how to prospect with a story, how to train using a story, and so on.

Passing the Torch

One of the goals of telling stories in sales situations is to get the buyer to open up and share stories in return. So, when you’re done with your story, always remember to pass the torch.

Sometimes, passing the torch involves little more than keeping quiet. With a moment of silence after a story, you create a natural opening in the conversation for your buyer to wade in with one of her or his stories. That’s how John Scanlon did it.

But sometimes you’ll need to be more proactive, prompting the listener. For example: “Enough about me. How about you?” “So that’s how it went with the other CIO. What’s your story?” “Those are the challenges my last client was facing. I’d be interested to know how it’s been for you.”

Everyone has a story to tell if given the chance. People want to tell their stories—they want to be heard, they want to connect, they want to be understood. It’s human nature. Pass the torch to your listeners and watch them run with it.

Story Tending

The idea of “tending” a buyer’s story came from a conversation when we reflected on the most memorable sales from our own careers. In each of the stories we shared, the common theme was that we knew the stories of the people who were responsible for making the decisions. We both recounted how we got our then-buyers to open up with us. We thought of words that represented how we got those stories from our buyers. The word tending came up. We tend to the things and the people in our lives that are important to us. If we make the idea of the buyer’s story important, we should tend to it. Why then don’t salespeople think of the word tending?, we asked each other. Isn’t it more apt than phrases like “diagnosing a buyer” or “getting their pains”?

Tending implies a completely different mind-set in the way we approach buyers. Rather than being narrowly focused on extracting a buyer’s problems or pains, a seller who tends a buyer expresses genuine caring and curiosity about the buyer’s whole story: where he was, where he is now, how he feels, where he’d like to be in the future and why. In doing so, the seller not only learns everything he needs to know about the buyer’s situation but also makes the critical emotional connection that can ultimately lead to the buyer saying yes.

In the workshop, we now ask participants, “What in your personal life do you tend?” Their answers usually include children, spouses, parents, gardens, and so forth— things that grow. We believe relationships and the conversations that foster them should be nurtured the same way. That’s what we mean by “story tending”—bringing a sense of caring and purpose to your sales calls and to the stories you and your buyers share.

A big part of story tending involves listening. In the next chapter, we’ll discuss the skills that will help make you a great listener. But story tending also involves making choices about which stories to tell. The goal is to help buyers open up and tell their own stories. In this way, storytelling becomes a back-and-forth collaborative process.

Reciprocity and the Story Ladder

If the ultimate goal of our stories is to influence buyers to believe what we believe, then we must get buyers to tell us their stories in return, to share the information that will help us help them. As a seller, use your stories to go first, telling stories that make points and that prompt buyers to tell their own stories on the same subject. Think of yourself as holding the buyer’s hand, guiding him up the ladder, letting him know it’s safe. One story begets the next, each a means to an end: your buyer’s yes.

Adam’s Climb Up the Story Ladder

Let’s go back to Adam’s story about the dangers of going it alone. Adam was stuck on a rung where he needed his buyers to acknowledge that they had a problem. Without that acknowledgment, the sale was going nowhere. He determined that the right tool for the job was his personal story about a time when he’d tried to go it alone and failed. After Adam went first and showed his own vulnerability, he passed the torch. His buyers then felt comfortable telling him their story, in which they confessed to being in a similar situation. In this way, the point of Adam’s story became the point of his buyers’ story, too—they’d moved up to the next rung together. A story begets a similar story.

In a more traditional approach, Adam might have broken out his slide deck or demo, drawing on his corporate product training and offering the buyers his value proposition. But then he’d have run into all the dangers of traditional selling techniques:

![]() We confuse the buyer. When we launch into detailed descriptions about our products, we force buyers to use left-brain processing to analyze the heaps of data we’re sending their way. Of course, the left brain has an unending appetite for information—give it some details, and it has to have more. The sales call quickly devolves into endless product hell.

We confuse the buyer. When we launch into detailed descriptions about our products, we force buyers to use left-brain processing to analyze the heaps of data we’re sending their way. Of course, the left brain has an unending appetite for information—give it some details, and it has to have more. The sales call quickly devolves into endless product hell.

![]() We create skepticism. As humans, we are inherently skeptical of other people’s positions and opinions. When a seller launches into a sales pitch and starts detailing her value prop, however persuasive or reasonable, she will trigger the buyer’s left-brain skepticism and scrutiny. We intuitively know when someone is trying to persuade us, and we instinctively resist it—it’s a natural defense mechanism. Also, any emotional connection made earlier in the sales call is likely to be diminished or to fly out the window at that point.

We create skepticism. As humans, we are inherently skeptical of other people’s positions and opinions. When a seller launches into a sales pitch and starts detailing her value prop, however persuasive or reasonable, she will trigger the buyer’s left-brain skepticism and scrutiny. We intuitively know when someone is trying to persuade us, and we instinctively resist it—it’s a natural defense mechanism. Also, any emotional connection made earlier in the sales call is likely to be diminished or to fly out the window at that point.

![]() We fail to connect with the key part of the buyer’s brain. Once a salesperson shifts from storytelling to traditional selling, he is trying to move the buyer’s head, not his heart. But it’s the heart—the emotional limbic system—that makes the decision to say yes. That’s the part of the brain that sellers need to be speaking to.

We fail to connect with the key part of the buyer’s brain. Once a salesperson shifts from storytelling to traditional selling, he is trying to move the buyer’s head, not his heart. But it’s the heart—the emotional limbic system—that makes the decision to say yes. That’s the part of the brain that sellers need to be speaking to.

Fortunately, Adam didn’t make the mistake of reverting to a pitch. He knew that stories aren’t just a way to open up a conversation but that they build on one another throughout a conversation. He also knew storytelling isn’t linear or serial—this story, then this one, then this one. Rather, stories can be used in different ways in different situations, depending on the buyer’s stories. And so, mindful of tending his buyer’s story, he offered a Who I’ve Helped story about a client of his who had faced similar problems. The point of his story was to show the buyers that their problems could be successfully addressed. He wanted them to understand how he could help them long before he ever had to break out his product information.

“Your situation reminds me of another IT director I worked with,” Adam said. And then he told them about Bob, a seasoned 20-year executive who was doing fine until compliance regulations mandated that his company implement a new security application. Given his experience, Bob thought he could handle the job himself, and for several months, things seemed to be going fine. But then it came time for his company to generate its first compliance report since the implementation of the new application. Trying to pull data from the company’s disparate systems was a disaster. “So Bob brought us in on a consulting basis,” Adam said, “just to put out the fire. But once we helped him integrate the security app across his systems, he realized we had the capacity and the know-how to do the same for all his applications. He enlisted our integration professional services, and by using our middleware with open APIs, he was able to make all of his systems work together.”

Instead of trying to persuade the buyers that he could solve their problems, Adam used this story about someone else who took a leap of faith and tried a new way. The story gave the buyers a sense of what was possible—a glimpse into their own future if, like Bob, they chose to buy. In this way, Adam was tending their big-picture story, collaborating with them to craft a resolution in which his products and services were the answer to their problems.

Then Adam passed the torch. “Anyhow,” he said, “your situation just reminded me of Bob’s.”

The buyers reciprocated with another story about their failed integration efforts, one that included a more detailed description of what they’d hoped to accomplish. By internalizing Adam’s last story, they had begun envisioning a solution to their own problems.

Instead of pursuing the traditional diagnose/prescribe dynamic, Adam had managed to turn the entire sales call into a collaborative sharing of stories. In doing so, he got the full story from his buyers—all the information he needed to figure out what their problems were and how he could help solve them. But instead of using this information to try to persuade the buyers, he kept using it to choose his next story. Each story was used with a purpose—as a means to get the buyers to open up and share a related story. Inviting a buyer to share her or his whole story requires tending, and tending requires real listening, which we’ll cover in the next chapter.