CHAPTER 5

COMMITTED AND LEAVING

David has worked for his organization for eight years, three years managing the same group. He is considered a high potential, is regarded as the likely successor to his boss, and periodically is asked to update top executives on his initiatives (something that is uncommon for someone at his level in this organization). He works long hours to produce excellent results for the company, and he is perceived by all as a highly committed and valuable employee. If you asked people who work with him, they would say David is exactly the kind of person they want and they only hope they can find more people like him to work there.

What they don’t realize is that David isn’t happy. While his pay is acceptable, it isn’t good. He has had some opportunities to grow at the company and has been told there will be more, but they are slow in coming. He is given too much work and doesn’t complain about it because everyone on the team is overworked. But it annoys him because he feels as if the company is taking advantage of him by not having enough staff to do the work. His boss is great—a real champion for him—but his boss can’t eliminate the politics David sees permeating the organization. So despite his stellar reviews and boss’s support, he is looking for opportunities in other organizations—constantly.

When last we spoke, David was continuing to keep an eye out for good opportunities while still working hard at his current job. It isn’t that he wants to leave. In fact, he wants to stay because he believes in the organization, likes his boss, and has had real opportunities to develop and grow both personally and professionally. But many days he wakes up in the morning feeling like he’s being stifled in his current job. So he keeps looking, all the while being highly productive, and waiting for things to get better, so he won’t have to leave.

MILLENNIALS ARE COMMITTED?

Millennials have been derided for a lack of commitment to their organizations. If we took the pessimists seriously, it would be easy to conclude that Millennials are ready to walk out the door at the drop of a hat. Yet our interviews and the data revealed a much more complex picture of the push and pull factors at play between Millennials and the organizations that employ them.

David is a perfect example. He is definitely committed to the organization. Yet he’s keeping an eye out for other opportunities because he isn’t completely happy with his current situation. He believes that if he keeps looking he is likely to find a position with better compensation, more opportunities, great people, and interesting work.

Millennials Are Committed … Because They Are (Mostly) Getting What They Need

Millennials are quite committed to their organizations. More than half1 say they are emotionally attached to the organization, about two-thirds2 say they enjoy discussing their organization with people outside it, and about two-thirds3 don’t intend to leave.

Why are Millennials committed? There are a variety of reasons, most of which are common to all generations. Among the most important are the following:

• They generally like the work they are doing. Sixty-nine percent say they are satisfied with their job.

• They like their organization. About three-quarters4 say they like working for their current organization.

• They think their organization does work that has a positive influence on the world. Almost three-quarters5 say that their organization behaves as a good corporate citizen.

• They feel that they have access to learning and development resources at work that will help them to improve their skills.6

•• They believe that their organization values employee learning and development.7

• They have friends at work, and 98 percent say it’s important to them to cultivate friendships at work.8

• The majority believe that their supervisors care about their well-being.9

Taken together, this paints a picture of Millennials who are generally committed.

The Point

Millennials are committed to their organization when they do work they enjoy, have access to learning and development, like their bosses, believe their organizations are having a positive effect on the world, and have coworkers they like and friends at work. Organizations that provide these conditions will reap the benefits that come from having a more committed workforce.

![]()

In Case You’re Wondering about Older Employees’ Commitment

Older employees:

• Generally like the work they are doing. Seventy-four percent say they are satisfied with their job.

• Like the organization they are currently working for (85 percent).

• Think their organization does work that has a positive influence in the world. Eighty percent say their organization behaves as a good corporate citizen.

• Say that they have access to learning and development resources at work that will help them to improve their skills (78 percent).

• Believe that their organization values employee learning and development (78 percent).

• Have friends at work, which 97 percent say is important to them.10

• Believe that their supervisors care about their well-being (58 percent).

![]()

Millennials Are Committed … They Don’t Want to Leave

Contrary to the stereotype, Millennials don’t prefer changing organizations every few years. In fact, Millennials would like to stay for a long time: about half11 say they would be happy to spend the rest of their careers with their current organizations. In our interviews with Millennials, a majority said they really wanted to stay with their current organizations—for the rest of their working lives, if they could. They clearly like the idea of a long, stable career.

For example, one Millennial started with his organization at the age of 19 during a work-study program. When we spoke with him, he said that if he had the chance, he’d spend his whole career there (he was the ripe old age of 23 at the time). When we asked why, he listed the reasons described in the first section of this chapter: he liked his boss and the people he worked with, he had good friends at work whom he had fun with (even while working), the organization continuously provided him with opportunities to learn and grow, he was paid well enough, and he thought the organization did good work. He told us that he’d be happy to spend the next 40 years with the same organization. He wasn’t sure it would happen, but he said he would be quite content if it worked out that way.

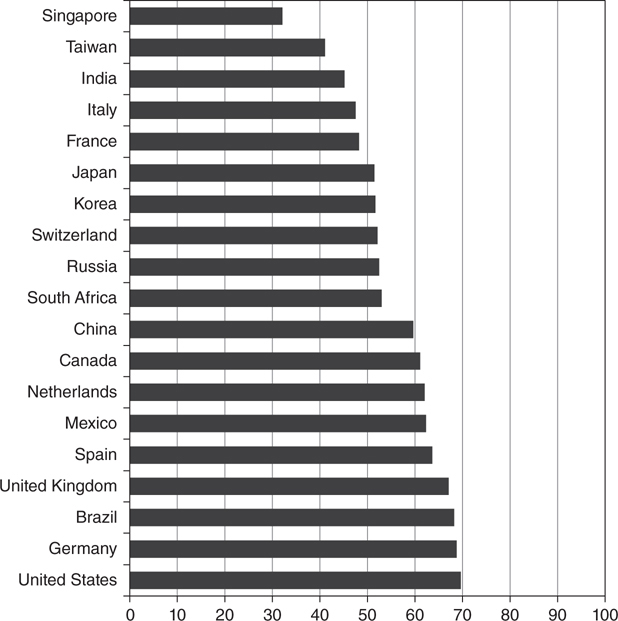

Many Millennials across the globe are planning to work for just one organization for a long period of time (see Figure 5.1). With the exception of Singapore, at least 40 percent of Millennials see themselves with very long tenure with at least one organization. The number is above 60 percent in Canada, the Netherlands, Mexico, Spain, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Germany, and the United States. This is different from the popular stereotype of Millennials wanting to frequently change jobs. The bottom line is that many people, Millennials included, do not like change for the sake of change, and changing jobs can be very disruptive. Unless they have a compelling reason to leave, people usually like to stay where they are.

FIGURE 5.1: Percentage of Millennials Who Expect to Work Nine or More Years for One Organization

The Point

Millennials would prefer to stay with one organization for most or all of their working lives if they could. A large percentage of Millennials around the world expect to be able to stay with their current organizations for a long time. Organizations that provide the conditions employees want will benefit from retaining the best staff.

Millennials Are Committed … They Want to Move Up Within an Organization

One common complaint about Millennials is that they aren’t driven, that they don’t want to move to the top and run organizations. Research doesn’t support that conclusion. A Pew study done in 2013 showed that 70 percent of Millennial men and 61 percent of Millennial women would like to be a top manager someday.12 Seventy percent of Millennials in Universum’s global survey said that they wanted to rise to the level of manager or leader in their organizations.13 Research by CareerBuilder reported in 2014 in Harvard Business Review indicates 52 percent of older Millennials (aged 25–34) aspire to a leadership position, in comparison with 67 percent of younger Millennials (aged 18–24). Both those numbers are higher than those for older employees (37 percent for ages 35–44, 23 percent for 45–54, and 20 percent for 55 or older).14 The bottom line: a majority of Millennials want to become leaders in their organizations.

This is precisely what we heard from Millennials during interviews and focus groups. Millennials expressed their desire to move up within their organizations and to make a difference (and make more money). At the same time, they were concerned about the toll higher-level jobs would take on them and their (future) families because they saw the kind of lives their supervisors were living.

Millennials’ supervisors had a similar perspective. They talked about how hard Millennials work, how many hours they put in, and how available they make themselves to ensure the work gets done. At the same time, they identified potential issues, such as Millennials still learning how to prioritize work and their personal lives. They saw Millennials’ drive to move up within the organization but thought that many had not yet developed the necessary skills to advance.

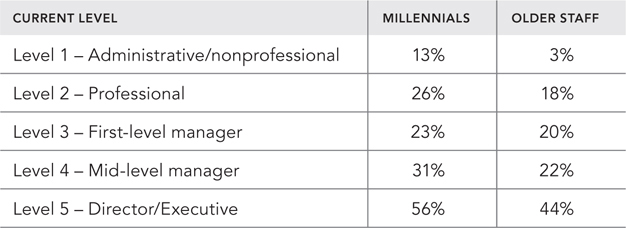

Consistent with what was reported by Pew and CareerBuilder, what we see is more nuanced than “Millennials don’t want to work hard enough to move to the top of the organization” or “Millennials don’t want to get to the top of the organization because they don’t want to work hard.” We find that Millennials overall are just as likely as their older colleagues to say that they want to move to the top of their organization. In fact, Table 5.1 shows that at each level in the organizational hierarchy, Millennials are more likely than their non-Millennial (older) peers to say they want to move up in their organization and work in senior leadership positions.

We think there are three reasons for this difference. First, some Millennials haven’t yet been exposed to the kinds of career experiences and setbacks that can lead people to temper their expectations and become satisfied with fewer promotions in their careers. Second, some Millennials are on faster career trajectories than their older colleagues—they have gotten to a comparable career stage in fewer years and therefore expect to continue to advance higher and faster than their older peers. Third, some older staff have a much clearer understanding of the pressures of working in higher-level roles and know they don’t want to make the necessary sacrifices to their quality of life; similarly, some Millennials likely will adjust down their desire for promotion over time.

TABLE 5.1 Percentage Who Want to Get to the Top of an Organization

The Point

Millennials do want to move up within their organizations. They are career oriented and want to progress to higher levels of authority and power. Just as in any generation, there is variation among them—not every Millennial wants to be a captain of industry. But a large percentage of them do, and that percentage increases the higher their current position in the organization. Millennials certainly are not lacking in ambition to get ahead. Employees need clarity from their organizations on what they have to accomplish, learn, and demonstrate to be promoted.

COMMITTED DOES NOT MEAN STAY NO MATTER WHAT

Millennials may be committed to their organizations, but about a third15 say they are looking for other opportunities.

This means that at least a third of Millennials are assessing the environment for better options right now—and even more will be doing so in the near future.16 Some Millennials are trying to escape a situation they don’t like, while others are trying to “level up” to a better situation, even if they are generally satisfied with their current situation. (“Level up” is a computer gaming term for moving to a higher level so you have access to better options in the game.) In other words, some are pushed to get out of a bad situation, while others feel the pull of wanting something better than what they currently have, even though they might be generally content to stay where they are.

Millennials are Leaving . . . Why They Try to Escape Their Current Positions

Sometimes Millennials leave to escape from unpleasant situations. Here are several examples of what they are trying to escape.

Overload

While Millennials are willing to work hard, at some point enough is enough. Many Millennials want to move from their current organization because they feel overloaded in their job, and they don’t believe it will be better in another position in the same organization. Part of that is about a desire for work-life balance, and part is about just having too much to do and not enough time to do it. Feeling overloaded is common among Millennials: 42 percent believe they can’t get everything done on their job, and 49 percent believe that because of the workload, they cannot possibly do all their work well.

The perception of being overloaded is an especially big problem for Millennials because of their orientation toward work. Remember, Millennials are highly intrinsically motivated, which means that they really care about the work they’re doing. As a consequence, thinking they can’t do something they care about well because they are overloaded is a big negative for them. They’re likely to find that situation depressing and may want another job where they can do what they consider to be good work. Employees don’t like to be trapped in situations where they feel they are doomed to failure from the start, which is what often happens to overworked employees. So rather than feel trapped, they find another organization where they believe the expectations are more reasonable.

![]()

You Can’t Ignore Their Stress Just Because They Chose the Job

People who take on high-powered jobs obviously know they are going to have more responsibility and greater workloads than in lower-level, lower-pressure roles. So why should a senior manager or executive worry about complaints of work-life balance or career advancement for people who have chosen the high-powered job? Because how they feel about their job matters.

If they consistently feel they can’t balance their work and their lives in a way they find acceptable, that can make them unhappy with their careers, result in poor performance, and compel them to leave for greener pastures. So whether or not you believe that people who choose high-pressure jobs should complain about work-life balance and career advancement, you need to understand that their feelings affect their commitment.

![]()

Millennials believe that if they control their work, they can reduce the overload. Sixty-six percent of Millennials say that having control over their work assignments is very or extremely important to them. (This is true for both men and women.) Slightly less than half17 of Millennials believe that they can control their work pace.

We spoke with one Millennial who had a particular problem with this. She was a high potential and also a candidate for burning out. She routinely worked 12-hour days, and she hadn’t had more than a day off in six months. She had to cancel her previous year’s vacation—after it had been paid for—because her bosses told her she couldn’t leave because it was a critical time for the business. She was a dedicated employee and canceled her vacation (the organization reimbursed her for its cost), but she didn’t get to reschedule it for another year. She was a prime example of someone who was seriously overloaded with work.

While this woman’s story is an extreme example, many Millennials experience work overload, some of which is unnecessary. Millennials are quite aware of how much more they could get done with more efficient technology and work processes. If they feel overloaded and see a fix that their organizations refuse to implement, they are likely to become even more resentful of the overload. If the overload could be reduced and the people in charge don’t take the obvious steps to do so, that sends a pretty clear message to the Millennial: management doesn’t care about the overload, so the Millennial should find a different place to work where it’s less of an issue.

© Randy Glasbergen, glasbergen.com

Organizational Politics

Even when Millennials are committed to the organization and its mission and are well paid, organizational politics is one aspect of work that could cause them to leave. For example, Millennials are very likely to say that they are looking to leave their organization if they believe (1) that there is a politically powerful group within their organization that no one ever crosses; (2) that it is easier to remain quiet than to fight the system; or (3) that pay and promotion are primarily based on organizational politics. Millennials dislike organizational politics (as do their older colleagues), and the more they see it, the more likely they are to say they are looking for a new job.

Unfortunately, organizational politics is an issue many Millennials encounter in their organizations. We find that more than a quarter of Millennials believe organizational politics is a real, significant, and negative issue for their organizations. They believe that employees are more likely to get ahead if they keep quiet, agree with the people in power, and tell those people what they want to hear (for more details, see Appendix 5.1).

Organizational politics is an especially big issue for Millennials who have very sensitive hypocrisy detectors and who value honesty. We know Millennials have a desire to “speak truth.” Millennials who work in organizations they perceive as being highly political—or for managers they perceive this way, even if the organization is more open—are likely to want to leave even if the organization is otherwise a good place to work. If they feel they can’t make a contribution or advance because of office politics, and if being political rather than being productive is required for promotion, they will want to leave even faster.

Bad Management

There is an old truism: people do not leave companies, they leave bad bosses. That is as true for Millennials as it has been for older generations. While the majority of Millennials (58 percent) believe that their managers care about their well-being, the bad news is that 42 percent think that their managers don’t. About a quarter don’t feel their supervisors are supportive, say that their managers don’t appreciate it when they put in extra effort, don’t believe their managers are forgiving of honest mistakes, and don’t think their managers understand when they have to prioritize their lives over work.18 One in five say that their managers show little concern for them. That means that between a quarter and a third of Millennials don’t feel their managers are meeting their needs.

Source: CartoonStock.com

In addition, many Millennials don’t trust their bosses much. Only 38 percent of Millennials say they trust their boss a lot, while 54 percent have some reservations about how much they trust their boss. About a third of Millennials report that their bosses order people around just because they can. These Millennials are flight risks.

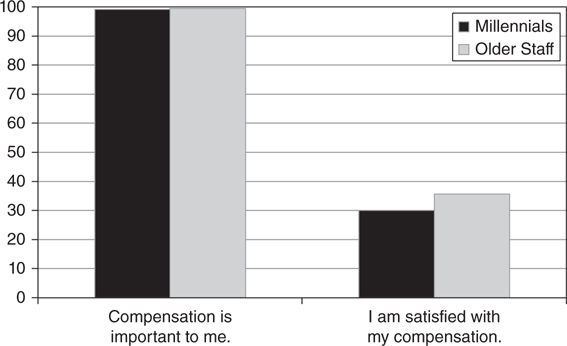

Unacceptable Compensation

A majority of Millennials think compensation is important and are dissatisfied with theirs (see Figure 5.2; note that the same is true of older staff). They think their pay and benefits are not fair recompense for the skills and effort they put into their work. Further, they believe they are underpaid in comparison with their peers within their own organization and in comparison with those at other organizations at the same job level.

FIGURE 5.2: Compensation Importance and Satisfaction

Why do most Millennials believe they are not fairly compensated? Because they are comparing notes with others about compensation, as we discussed in Chapter 3. It is likely that a majority of them have looked online to see what others are paid. While the accuracy of the data on these websites is often questioned, people still refer to them and are influenced by the information they find. In addition to looking at compensation comparisons online, a large percentage of Millennials discuss their compensation with their coworkers, family, and friends.

So nearly all Millennials think compensation is important, yet only about a third of them are satisfied with their compensation. Is it any wonder that many of them look for other opportunities?

The Point

Millennials will look to escape from situations where they have a bad supervisor, encounter too much office politics, feel overloaded, or think they are underpaid for the work they are doing. Organizations need to make sure that they are staffed to reduce overload, that managers are trained and have time to be good supervisors, that compensation is appropriate, and that the organization rewards productivity more than it does office politics.

Millennials Are Leaving . . . Why They Try to “Level Up” into a Better Situation

One of the best indicators that Millennials are committed is that the majority want to stay for a long time and are interested in becoming leaders in their current organizations.

But even those who are committed, feel generally happy with their situation, and say they would like to stay forever recognize that other opportunities might be a better fit for them. They could be perfectly content to stay in their current role, but they are drawn to “level up” to a new role that offers more compensation, better work-life balance, increased developmental opportunities, and so on. As a result, they keep an eye out for opportunities that would be an improvement over their current situation.

Better Compensation

Compensation is important to 99 percent of Millennials (see Figure 5.2) and very or extremely important to 81 percent of them. When they look to move to another organization, they are looking for greater compensation, either immediately or in the near future.

Millennials told us that they have real alternative job prospects that are potentially better than their current positions. When asked, more than two-thirds19 said that if they wanted to move, they could find an acceptable position. Eighty-nine percent believe that they would be paid more than they are currently if they took a new job.

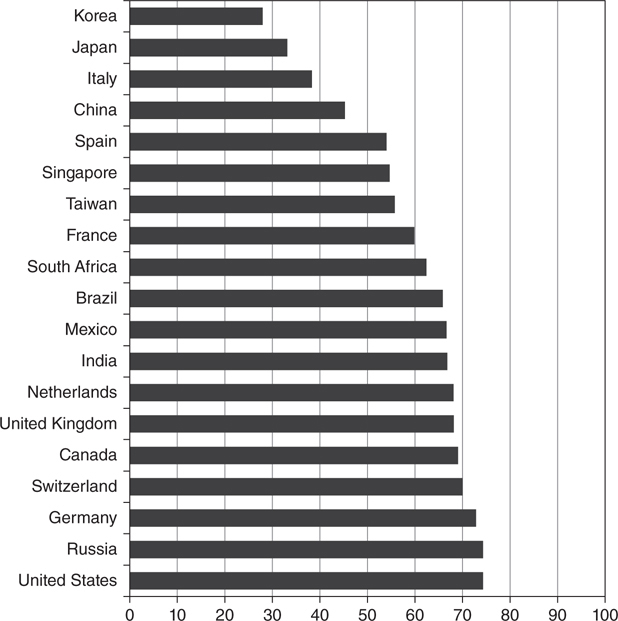

Around the globe, Millennials know (or believe they know) that they have viable options at other organizations. More than 50 percent of Millennials in most countries (see Figure 5.3) say that they know of other organizations that would offer them a job if they were looking. This makes the threat of them leaving both real and credible if they don’t get the advancement, learning, and community they want from their current organizations.

FIGURE 5.3: Percentage of Millennials Who Know of Organizations That They Believe Would Offer Them a Job If They Were Looking

Why do Millennials believe it would be so easy to find a job with better compensation? Part of the reason is undoubtedly because of how frequently many of them are called by headhunters about other jobs. More than 70 percent of Millennials said that they were contacted at least once in the previous six months about a job at another organization. For 30 percent it was more than four times. And for 16 percent it was 10 or more times.

These contacts aren’t just calls. These conversations often include discussions about salary ranges and promotions, as well as learning and development opportunities at the new organization. Millennials are often being pitched a new option that pays better immediately and has better long-term prospects than their current position. One way to think of these is as sales calls. The person calling has a job to sell to the Millennial, and the recruiter wants to make the job as attractive as possible, while remaining relatively accurate. So framing the job as having higher compensation and greater development and advancement potential would benefit the recruiter. One manager questioned the reality being presented in these calls:

A Millennial who used to work for me received a call and was told about a new job where he would be paid 50 percent more, have a guaranteed promotion and pay increase in six months, be able to leave work earlier, get more professional development, etc. He went for the interview and was promised those same things by the company. After he received the job offer, he came back to me and asked if I could match it. I couldn’t. I told him that I thought he was being sold something that wasn’t going to happen, and I wished him luck. He took the job and left. I’ve heard from a few of his friends that the job didn’t turn out to be everything he was told it was. I’m not surprised. In these cases, they rarely are.

Regardless of what people think is happening in these calls, whether they are presenting a realistic alternative option or a best-case scenario that almost never happens, they change the employees’ reference points for their current positions. How much people think they should receive and how happy they are with what they receive are highly dependent on their reference points.

For example, Enrique found his compensation acceptable until he received a call from a headhunter. During the call the headhunter said Enrique could be making 30 percent more than he currently was if he took the same job in a different organization. He wasn’t sure he believed her, so he asked around and found that both his peers at his current organization and people on websites that track compensation were being paid more than he was for basically the same work. A week later, he had a conversation with his boss about how unhappy he was with his compensation. Enrique’s compensation hadn’t been reduced that week, but his perception of it had changed as a result of the new reference points.

We found that this is a pattern globally. For example, India has a very hot labor market for highly skilled employees. Top talent among Millennials is headhunted frequently, and some move every 6 to 12 months for increasingly larger salaries. When we interviewed people in India, we asked about this and were told that it was common. We were also told that, not surprisingly, sometimes the new job turns out to be not all the Millennial was promised.

A headhunter selling these jobs as opportunities for advancement is capitalizing on a common worldview of Millennials. Millennials expect their compensation to go up, so people calling to offer them a position that pays more isn’t a surprise. Millennials are as optimistic about their earning potential as Gen Xers were when they were younger.21

So nearly all Millennials think compensation is important, only about a third of them are satisfied with their compensation, and a majority of them get calls a couple of times a year suggesting they aren’t making as much as they could be. Is it any wonder that many of them look for other opportunities?

Having a Life

Millennials will look for another position if they feel that their work-life balance is off. Almost two-thirds22 feel work interferes with their personal lives. In many cases, these same Millennials work in organizations with work-life programs and initiatives. Unfortunately, about a third23 believe that if they participate in work-life programs, they will be perceived as being less dedicated than those who do not use them. So they look for organizations where they believe they can meet their personal needs for work-life balance without being perceived as less dedicated for doing so.

For example, one man we interviewed talked about how important it was for him to play on his football (soccer) team. He had played on this same team for a few years without work interfering with his evening practices or his weekend games. But as he moved up within the organization, he found that work began to interfere. It wasn’t just interfering with the occasional evening practice, it was affecting his ability to participate in tournaments on the weekends.

He was becoming increasingly frustrated because the demands were shifting from occasionally having to do a bit of work at home on the weekends or answering e-mails on his phone to being physically in the office on weekends. For the past few months, he had been required to come into the office for half-days almost every weekend, and as a result, he had missed some of his team’s tournaments. He told us that if this pattern continued much longer, he would start looking for another job. While he said that playing a sport wasn’t the most important thing in the world, it was important to him, and he didn’t see why his work should consistently prevent him from having fun on weekends.

Part of the issue with work-life balance is the constant connectivity that is common for many employees today. In many organizations, Millennials expect to be connected with work almost all the time through their devices. Research shows that this is in fact their reality: many of them are in contact most waking hours of the day—and on weekends.

Given the constant connectivity, one aspect of their work that can help Millennials manage their need for work-life balance is the amount of flexibility the organization allows. Millennials expect flexibility. It is critical to them because of the way they live their lives, because they are independent, and because it is logical. While it makes sense that some work has to be done in an office at a particular time, it doesn’t make sense to have no flexibility at other times.

Millennials are committed to their organization when it offers the work-life balance they want. When it doesn’t, they look to leave because they believe they will get it somewhere else.

Better Development Opportunities

Millennials move to other organizations because they believe they will have more and better development opportunities there. Millennials are quite concerned about stagnation, both in their careers and in their development. Eighty percent believe that they need to continuously improve their professional skills and capabilities. They want to remain competitive in the workplace, they like to be challenged to do new things, and they feel strongly about making a contribution. They realize that if they don’t continuously improve, they won’t be able to grow and contribute to their organization.

Millennials place a high priority on development. Half say they work for a particular organization specifically because of the career opportunities. About three-quarters say they see their position as an opportunity to develop technical expertise,24 develop leadership potential,25 and demonstrate their abilities as a leader.26

Almost three-quarters say that they have access to learning and development resources at work that will help them improve their skills.27 Yet about a quarter of Millennials tell us they are not getting the development they need to make them feel they are continuing to learn and improve.

One likely reason they don’t think they’re getting enough development is a lack of time. Though they have access to development, a majority28 of Millennials say they don’t have enough time to engage in development the way they need to. A number we spoke with said they weren’t given adequate time to really think about and assimilate what they were learning (which is related to our earlier discussion about overload). They felt much of the learning was simply washing over them rather than being integrated into their work.

The lack of time for on-the-job development contributes to Millennials’ perception that the organization is treating them as independent agents, not as valued contributors. From the Millennials’ perspective, if the organization wants the employee to learn and is going to benefit directly from the employee’s development, then the organization should provide the resources for the employee’s development (e.g., both provide work time to do the development and pay for it). If the organization does not provide the resources, then the presumption is that the organization doesn’t care that much about either the development or the employee. So Millennials move toward situations where they believe they will be more likely to get the development they need and have the resources provided to do it.

Better Promotion Opportunities

Millennials move to another organization because they believe they will have better opportunities for promotion at the new organization. Historically, many managers and leaders believed (and some still do) that people needed to spend a certain number of months or years in a particular position before they could really do the job well and gain all of the knowledge possible from that position.

The problem with that view is that people don’t learn or integrate learning at the same rate. Think of it like learning geometry. Some intuitively grasp it and can work through the proofs quickly and accurately in a minimal amount of time. Having them do additional proofs for weeks on end will not result in a substantial improvement in performance. Other people don’t intuitively get geometry. They really benefit from the additional time on task, and substantial growth can be seen over a much longer period of time.

The same is true at work, and Millennials realize this. They understand that they will master some skills quickly and others more slowly. What they don’t accept is a manufacturing mindset that says that it will take a precise amount of time before they have learned everything they need to learn in that position. Millennials realize that everyone is different, and while a one-size-fits-all approach is efficient for an organization, it doesn’t meet their needs as individuals. Remember, they believe organizations look at them as free agents, so they aren’t going to trust organizations to keep them on staff for the long haul. They reject the idea of “wasting” a couple of years in a position beyond the point when they stop learning just to accommodate the organization’s planning needs.

For example, a young woman in one organization had been in her position for a few years with consistently strong results. She was considered an excellent manager, and her work was highly valued by the organization. After a few years in the role, she felt she was stagnating. She asked to be promoted into a position in another division so she could grow and learn. She had found the open position on her own. The other division wanted her to fill the role but wouldn’t take her without permission from her current bosses to move. She asked multiple times over nine months, and every time she asked she was told that it was an excellent idea and her bosses were working on it, but she did such a good job that it would be difficult to lose her. Even though they thought it would be difficult, they said they would figure it out. After nine months of this back-and-forth, she said that she wanted to be moved within six months. They agreed that would happen. And six months later she did indeed move—to another organization.

What happened? The organization didn’t move her because it was inconvenient. The organization benefited from keeping her in her current position and would have been happy had she done the exact same thing for another 20 or more years. The organization looked at her as a cog rather than as a person who wanted to develop and grow—and who could leave if she didn’t feel that she was developing and growing. They lost her because she wasn’t willing to sacrifice her growth for the organization’s convenience.

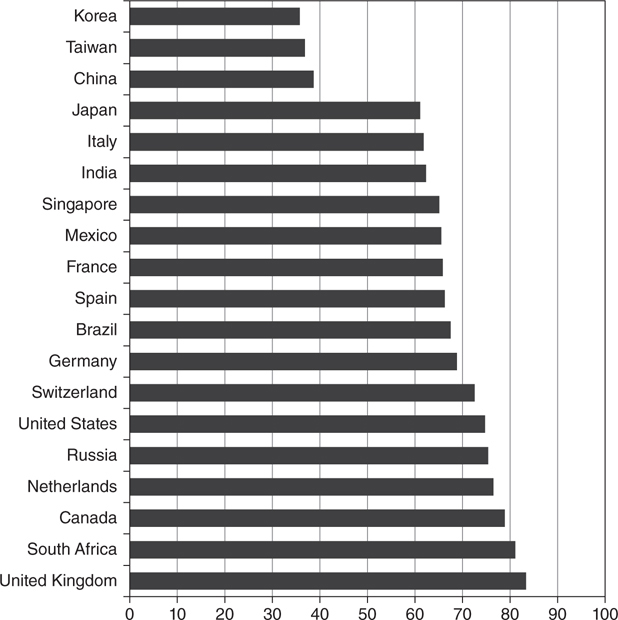

The belief that people should not have to stay in a role for a minimum number of years before being promoted is fairly consistent around the world. In most countries in our sample, a majority of Millennials (more than 60 percent) actively disagree with the perspective that people should expect to spend a minimum numbers of years in a job before they can be promoted (the exceptions are Korea, Taiwan, and China, where fewer than 40 percent of Millennials disagree; see Figure 5.4). In addition to those who disagree, 18 percent say they are neutral about whether people should have to stay in a position for a specific number of years. This means that, in all countries, at most one-third of Millennials say that people should stay in a position for a minimum number of years before they can be promoted, regardless of performance. That ranges from 7 percent in South Africa and the United Kingdom to 32 percent in China and Taiwan.

FIGURE 5.4: Percentage of Millennials Who Disagree That People Should Stay a Minimum Number of Years in a Job Before Promotion

A key component of this perspective is the role of merit. Millennials who don’t believe that people should have to stay in a position for a minimum number of years think that if people are qualified for promotion, if they are stagnating and not learning, there is no justification for holding them back just because someone believes they should be in the position longer. At its core, this is a generation, globally, that clearly believes in promotions based on merit more than on time in the position.

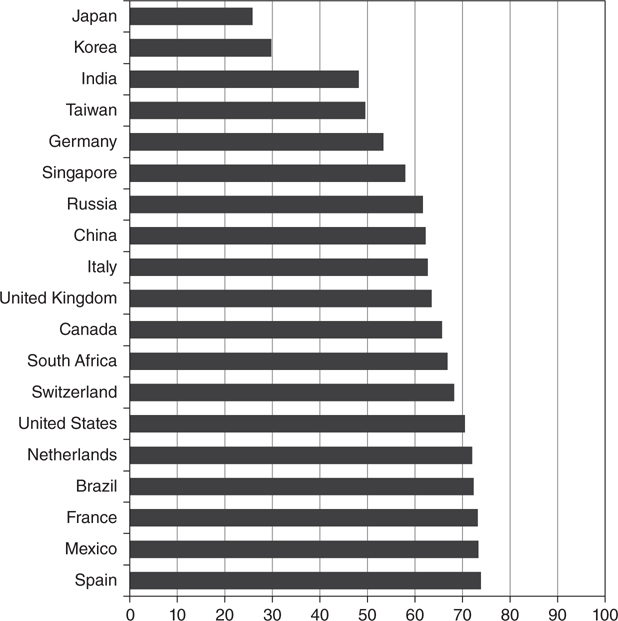

While the majority of Millennials in most countries are satisfied with their progress toward meeting their advancement goals (see Figure 5.5), the fact that more than one-third are dissatisfied with their progress indicates a large source of potential turnover.

FIGURE 5.5: Percentage of Millennials Who Say They Are Satisfied with Their Progress Toward Meeting Their Goals for Advancement

For those who aren’t happy with their speed of advancement, sometimes leaving is a good move for them because the organization really is too slow to promote, and the Millennial would stagnate if he or she stayed longer. On the other hand, sometimes moving up fast backfires, as shown by the story of a young man named Dave, who was a high flyer in his company. Dave’s group had been responsible for revenues far above what was expected, largely because of his leadership. He agitated for promotion and higher compensation and was promoted, received a pay increase, and was given a greater scope because of his team’s performance. He was a big success story—until he crashed and burned. Though his team’s performance was exceptional, his organizational maturity was not.

There were early inklings of his organizational immaturity—for example, when he was grandstanding about his contributions to the organization without giving credit to colleagues. When the boss saw Dave’s pattern of behavior, he tried to get Dave coaching. He wanted Dave to understand the political nuances he was missing so he would stop burning bridges unnecessarily within the organization, but Dave refused. Dave believed that his performance would protect him. Besides, those other people were just trying to take credit away from him or get in the way of the great work he was doing because they were jealous. He continued to engage in behavior toward others that undermined his leadership and the leadership of his peers, including behavior that angered others for no productive reason.

Over time, the animosity grew, and eventually he was found to be doing things that were embarrassing to the company. When this came out, Dave was offered the choice of a demotion, so someone could help him develop greater organizational maturity, or leaving the organization. He left. This is an example of a situation where believing in promotion solely as a function of performance without the attendant organizational maturity resulted in derailment.

Both of these examples (the woman who eventually left after giving the organization plenty of warning and the man who left after a stunning display of organizational immaturity) are reality for some Millennials (and some older staff as well). Many employees believe they should be promoted solely based on performance and will start looking for other positions when they are not promoted despite their good performance. Others put in time and ask to be moved but aren’t because the organization doesn’t prioritize their promotion or development needs.

The reality in many cases is that employees may be ready for promotion, and you may want to promote them, but they can’t move easily because a suitable position is not available—it’s “blocked” by someone in it who isn’t going to move any time soon. It is critical to find a way for these people to continue to learn and develop in their current roles through special assignments, additional responsibilities, and so on.

Many Millennials (and others) move to a different organization because they feel that their opportunities for development and promotion will be better at the new organization. Millennials are looking to leave, even while committed to the organization, because they want to keep learning, growing, and moving up. For Millennials, promotion is partly about building skills. If they feel they are stagnating at their current organization, they will look elsewhere to make sure that stagnation does not continue.

Belonging to a Community at Work

When Millennials leave, they may be looking for an organization and coworkers whose values align with their own. If a Millennial decides that he (or she) doesn’t believe in the mission of the organization or doesn’t agree with the manager’s priorities, he may feel he doesn’t belong. This may cause him to look for a new job.

Relationships in the workplace also contribute to feelings of belonging. While Millennials may love technology, they also want to interact with people. Their relationships at work are critical both to their self-concept and to their commitment at work. But what happens if they work for a manager who doesn’t prioritize getting to know fellow workers or developing close relationships with coworkers and, as a consequence, is dismissive of the Millennials? What happens if a Millennial isn’t able to find friends in the workplace? That Millennial is more likely to feel out of place and will look elsewhere for a position that feels right.

For many Millennials, the feeling of belonging may be split between the organization they are currently employed by and the profession they have chosen. In many industries, one of the shifts has been away from employees feeling they are a member of the organizational family to feeling they belong to a profession and happen to work for one employer (for now). In fact, many Millennials personalize their professional membership in the way people in the past may have personalized their organization. For example, a majority of Millennials feel complimented personally when someone compliments someone else in their profession,29 and they refer to other members of their profession (regardless of the organization they work for) as “we” rather than “they.”30

This means that for many Millennials, “belonging” is partially independent of their organization. If they leave the organization, they take the sense of belonging that arises from their professional identification with them. So for some Millennials, the need to “belong” within the organization may be reduced by a strong feeling of belonging to their profession.

When Millennials don’t feel they belong, they may start looking for what they are missing, whether that is an organization (or a manager) whose worldview is closer to theirs or coworkers and supervisors who care about them as people.

The Point

Millennials will look for a new job that raises some aspect of their life to a higher level. They often look to improve their compensation, work-life balance, promotion and development opportunities, or to find a sense of belonging to a community. Organizations that see retaining talent as a strategic advantage need to be aware of this desire to “level up” and provide options for employees that have this need.

CONCLUSION: MILLENNIALS LEAVE BECAUSE THEY BELIEVE THEY CAN GET SOMETHING BETTER ELSEWHERE

The evidence shows that while Millennials are committed, they may also be leaving. But people don’t leave unless they have other opportunities they consider viable, and Millennials are no different. If the economy or something else prevents them from moving, they won’t move. On the one hand, 37 percent of Millennials say that poor economic conditions have influenced their decision to stay in their current job in the past. On the other hand, currently a majority of Millennials say they could think of a number of organizations that would offer them a job if they were looking to move.

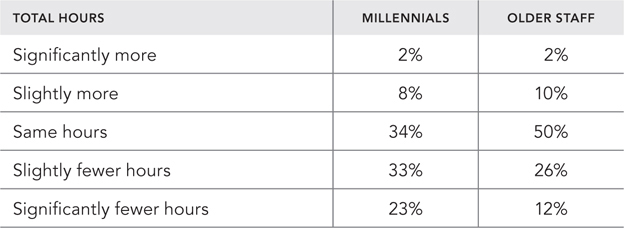

Millennials believe that jobs are abundant for them because headhunters often call many of them about other jobs and tell them they will have higher compensation and greater potential for development and advancement. In addition to better pay, a majority of Millennials believe that if they took an alternative job (with equivalent pay and responsibilities), they would work fewer hours. We might question whether this is a “grass is greener” phenomenon, where having more experience would provide the Millennials with a more accurate perspective of what is likely to happen. Evidence in favor of that interpretation comes from older employees’ responses about the likely work hours in a new position: they were much less optimistic than were Millennials that their work hours would decrease (see Table 5.2).

TABLE 5.2 How Many Hours Would You Work If You Took a New Job?

With their greater breadth of experience, older staff have a different perspective on alternative job opportunities: they don’t necessarily believe it is going to be better somewhere else. Millennials, in contrast, are more likely to believe it is going to be better somewhere else, and they want that. They want to be where they have the best combination of compensation, interesting work, people they like, and work-life balance. Because they believe that there is something better out there, they keep looking for it.

Given that Millennials are simultaneously committed and leaving, the following sections describe some actions you can take to work more effectively with them whether you are a team member, a manager, or a leader.

Recommendations for Working with Millennials as Team Members

Millennials are very committed to the work, their teams, and the organization—for as long as they are there. While they may leave for a better opportunity, that doesn’t mean that they aren’t committed while they are working with their teams. They’re willing to put in long hours and do what is necessary to get the work done.

![]()

How Different Are Millennials, Really?

Like Millennials, older employees are committed. In fact, a majority31 would like to spend the rest of their careers with their current organizations.

Though they are committed, like Millennials, they are keeping an eye out for other opportunities. Similar to Millennials, they feel overloaded, don’t feel they can control their work, aren’t satisfied with their compensation, and feel that work interferes with their personal lives. A majority of those in the older generation believe they can’t get everything done on their job,32 and more than a quarter33 believe that because of their workload, they cannot possibly do their work well. As with Millennials, it is likely that this is partly a result of not having control over their work. Having control over their work assignments is very or extremely important to them, but only about half believe that they can control their work pace, which is about the same percentage as Millennials.

Like Millennials, older staff think compensation is important, and most aren’t satisfied (see Figure 5.2). Almost all (99.5 percent) of those older than Millennials say that compensation is important to them, but only 36 percent say that they are satisfied with their compensation. Similarly, about three-quarters of older employees have received at least one call from headhunters in the past year. Like Millennials, more than half34 feel work interferes with their personal lives.

![]()

At the same time, they believe that they have a responsibility to themselves to keep an eye out for better opportunities. They don’t think the organization is going to look after their best interests, so they have to. This benefits those working with them—Millennials believe that they have to learn and perform well continually so they have greater opportunities for development and promotion. This attitude can help their coworkers continue to learn as well and achieve more.

Your Millennial colleagues can benefit from your experience. They value the advice and mentorship provided by their teammates, so if you have insights that would help them gain a more realistic understanding of their opportunities, share them. They will welcome hearing what you have to say about chances for promotion internally and opportunities at other organizations. At the same time, though, make sure you listen carefully to their hopes and desired career outcomes. No two people want exactly the same things from work, and it’s important to keep in mind what Millennials want when you offer your perspective. Recall that they want guidance but don’t want to be told what to do, so sharing your experiences needs to be just that. Share, but don’t sound like you know what’s best for them just because you were their age once.

Recommendations for Managing Millennials

People generally don’t like leaving where they work unless things are going poorly. Even when they have really attractive offers elsewhere, it can be hard to leave everything and everyone they have worked with over the years. Millennials want to stay and contribute—if they are given the opportunity to do interesting work, to grow, and to be a welcome member of the team. Millennials value the friendships and community they build at work. They will often welcome the opportunity to stay so they don’t have to give up the life they have built at the organization, but they will need your help to solve the challenges they are facing. Managers who work to make that happen will make it easier for Millennials to decide to stay.

1. Provide good management and minimize organizational politics.

If you want to retain employees and keep them happy, do everything possible to improve the quality of management and leadership. This includes minimizing organizational politics. Employees are turned off when they see the role models above them engaging in counterproductive behaviors and being bad leaders.

People often remember the negative and don’t remember the positive. One bad incident can have a much bigger impact than a collection of positive experiences. You can focus a great deal on making the organization a better place to work and getting rid of internal politics only to have your efforts undermined when a highly visible person does something out of line in a very public way. You and your peers on the leadership team may work quietly to reprimand that person because doing something quietly is often the best way to get such a person to listen, not be defensive, and fix the problem. Yet that approach is often invisible to the people who saw the initial bad behavior, so they may conclude that the offender got away with it. Keep this in mind and look for ways to send a message to the larger organization about what behaviors are acceptable or not, and how people are going to be held accountable for unacceptable behavior, and reinforce these messages as often as you can.

2. Help them get development.

Learning and professional development are key to what almost all employees, including Millennials, want from work. Providing them with developmental opportunities is a no-brainer: they benefit from the skill development and can apply those skills in future tasks while they work for you. Development can be a double-edged sword if you build employees’ skills but don’t give them an opportunity to use them—they might choose to leave for an organization that will put their skills to good use. It is very difficult to find the right combination of skills and organizational fit for people hired from outside, so developing your current Millennial employees and finding ways for them to use their newly acquired skills can provide one of the best returns on investment available anywhere.

Focus on creating these developmental opportunities for your direct reports. HR has a role to play in career planning, but the real responsibility for ensuring your employees get the developmental experiences they need falls on your shoulders. You are the one best suited to identify opportunities for them to develop on the job.

It has long been known that the best development happens through work. Classroom and online training are supplementary to the most impactful learning, which happens on the job. Working with your employees to figure out together where they need to improve and how to do it is one of the most important tasks for any manager. If you do it right, there’s a double benefit. The employee will grow and be positioned to take on new responsibilities, and you will have an employee who is more dedicated, willing, and able to contribute because you gave her the opportunity to develop.

3. Make Millennials want to stay by providing good reasons to stay such as promotion, development, good pay, community, and good bosses.

You can greatly increase employees’ desire to stay with your organization by getting the fundamentals right. Pay them right, and give them the opportunity to be promoted. Provide them with opportunities to find and work with people they get along with, both peers and supervisors. Do all of that and employee retention will be high.

Most important, keep in mind that employees decide to stay because of the entire package the organization provides, not just one aspect of the job, and that you help create that package for them. Most want either an actual promotion or at least some recognition that they are advancing in their careers. The opportunities to learn, apply that learning on the job, and be recognized by their supervisor and peers are aspects of the job they desire. A team that has a positive culture, where the team is productive and enjoys working together, can be a powerful antidote to the grass-is-greener allure of other organizations. The precise mix of what works will vary from person to person. Engaging employees in conversations about what they want and how to improve their job and the organization also helps.

4. Reduce overload and work-life imbalance—they are real issues that will drive Millennials away.

Burnout is a big issue in organizations today. As a result of many organizations’ nonstop efforts to improve productivity and reduce labor costs, workloads have increased for most employees. Because Millennials are the lowest in the hierarchy and least able to say no, they are particularly vulnerable to overload from too much work.

As a manager, keep in mind two important facts about workload and stress. First, just because you worked hard to get to where you are, that doesn’t mean others will necessarily embrace that choice the same way you did. For some people, a daunting amount of work is a turnoff that can lead an otherwise highly productive person to walk out the door. Which is worse: easing some of the workload or trying to replace someone who leaves? Not only may a suitable replacement be difficult to find, but if you lose the headcount in your budget you may not get to replace the person at all. There are real costs to turnover: the decreased productivity of your group working with less than a full team, the financial cost to find and train a replacement, and the potential cost of losing the headcount. Reducing the workload, spreading the work among more people, or extending deadlines may be more cost effective than dealing with high rates of turnover.

Second, the demands of the workplace have increased over time. Companies continue to find more and more ways to squeeze ever greater productivity out of the same number of people. Part of this is about working smarter, which no one would object to (and which Millennials embrace). But the reality is that the sheer amount of work and the interruptions of home life have increased over the years. At a certain point, the volume of work can get to be too much, even for your most productive people. These dedicated professionals will work really hard for you, often making sure they finish that one last big project that absolutely had to get done—before turning around and walking out the door. That’s what frequently happens if you ignore their real and legitimate concerns about work-life imbalance. The more responsive you are about relieving the stress of work, the less likely it is that Millennials (and other employees) will leave.

5. Provide development opportunities to bind them more tightly to the organization and improve retention.

Professional development is not about pacifying employees; developing your people gives your organization a competitive advantage. When people are given the opportunity to develop and improve their skills and professional standing, they contribute more to the organization and are more committed to it. That binds them ever more closely to you and can reduce turnover.

Managers play a central role when it comes to their people’s development. Some employees aren’t aware of the available developmental opportunities. Some will have a good idea but will need help with the specifics. Others may know the details quite well but not feel comfortable asking to participate. And still others may think they should be able to take advantage of an opportunity for development but don’t have realistic expectations about what’s involved or whether they are suitable candidates for it.

While development is critical to retaining employees, it can feel threatening to take some of your best talent and send them off to do other things. Will they have enough time to get their regular job duties done? If they go on special assignment, who will cover their work while they are gone? If they get exposure to other parts of the organization, will that make them want to leave your group for another? These are all legitimate concerns, but none is an excuse for denying employees the developmental opportunities they need—if those opportunities make sense for both the person and the organization.

Though you might want to, you can’t keep your best Millennials with you forever. It is likely they will want to—and need to—go and learn someplace else because their current position won’t provide enough opportunities for them for the next 30 years. Rather than keeping them tied to you, there are benefits to helping them grow and explore other opportunities. You will be helping to develop the talents of employees who can contribute to your organization’s success long after they have outgrown the tasks they are doing for you. And they just might stay longer and be even more engaged precisely because you trusted them and gave them the opportunity to develop, whether in their current positions or elsewhere in the organization. Both those options are better than having them walk out the door in frustration simply because you tried to hold them back. Yes, they may leave you to do something else within the organization. But better that than they leave the organization altogether—to work for your competitors!

6. Understand that they may not be happy with their progress, and that doesn’t necessarily mean there is anything wrong.

Almost all employees, regardless of generation, want to progress as quickly as possible. So it’s perfectly reasonable that Millennials will express their strong desire to progress and be promoted as quickly as possible. (On the flip side, when they don’t, people claim that they aren’t ambitious.) Yet employees’ desire for progression and your organization’s ability to satisfy their hopes and dreams may be very different.

As a manager, you don’t need to worry about this (much) because the vast majority of employees are realistic about what an organization can do for them, even though they might not admit it to you. Though they may ask for the corner office, in most cases they realize they are more likely to get a small bonus or a relevant developmental opportunity. There’s nothing wrong with stating clearly what you can and cannot do for them vis-à-vis promotions and development. You need to be aware, however, that if you don’t satisfy their needs, they could decide to go somewhere that will. You have to weigh the cost of providing quicker advancement or additional learning opportunities (to improve the chances of advancement) against the cost of finding replacements if employees decide not to wait around for that promotion.

Five Points to Remember

1. Millennials will leave if their needs for promotion, advancement, development, community, and appreciation aren’t met.

2. Millennials want to work within a community that matters to them—they want those they work with to care about them as people.

3. Pile too much on Millennials’ backs and they will break—just like the rest of your employees.

4. Learning and growing are important to Millennials because they know they have to keep developing their skills to remain employable.

5. Millennials can leave—but they don’t necessarily want to.

![]()

Who Millennials Are and What They Want

Millennials:

• Are committed to their organizations

• Like their work

• Feel like they are learning

• Want development

• Have friends at work

• Like their bosses and their organizations

• Would like to have long-term careers with their organizations

• Will leave if they can find a position that better meets their needs

• Are more likely to leave if they

![]() Feel overloaded

Feel overloaded

![]() Encounter too much organizational politics

Encounter too much organizational politics

![]() Don’t think they have good bosses

Don’t think they have good bosses

![]() Think they can get better compensation elsewhere

Think they can get better compensation elsewhere

![]() Believe they will have better work-life balance elsewhere

Believe they will have better work-life balance elsewhere

![]() Believe they will have better development and promotion opportunities elsewhere

Believe they will have better development and promotion opportunities elsewhere

![]() Don’t feel part of a community at work

Don’t feel part of a community at work

![]()