The First Attempts

Abstract

This chapter describes the first initiatives of social networking sites that were born at the start of the twenty-first century through two of the most representative examples. Nature Network was the first scholarly site that implemented forums and discussion groups with the purpose of establishing an online community around the scientific debate. At the same time, BiomedExperts and UniPHY attempted to build a network of experts that favoured the discovery of highlighted authors and the establishment of new contacts. From different approaches, both proposals tried to lay the foundations of academic social networking. However, this chapter reviews and discusses the causes of their failure and the importance of their contributions to Science 2.0.

Keywords

BiomedExperts; expert directories; Nature Network; UniPHY

The first social platforms on the Web arose as exploratory services that were intended to create online academic communities using a range of basic tools that allowed connection between members. These sites were born as experimental platforms from different approaches. In some cases, there were services that concentrated their attention almost exclusively on communication tools about which users shared information and discussions (Nature Network). In other cases, the network was simply an expert database where users would be able to find other partners with similar research interests (BiomedExperts, UniPHY). However, in general, because these platforms were created from a pre-conceived and limited concept of online social networking they suffered from excessive intervention on the part of site administrators. Perhaps these corseted structures promoted the swift stagnation of these sites and in consequence their rapid closure. As will be seen, these pioneer services lacked many of the social networking instruments and offered little freedom of action; however, it should not be forgotten that they opened the path to the next generation of academic social sites, suggesting new forms of contact among scholars. The disappearance of these sites should remind us of the changing nature of the social web and that services that are successful today will soon become obsolete if they do not recycle the functionalities they offer to their users.

This chapter suffers the major inconvenience that every site analysed has now disappeared. The reason for this was that a major part of the information on these platforms was not taken first hand and was needed to gather external sources to describe these services. In many cases, it was not possible to access the site, while in other cases, a limited part of the site was only available. As a result of this, it is possible that the information on some sites could be somewhat incomplete and inexact.

2.1 Nature Network

Nature Network was the first web service that attempted to create a networked community of scientists around discussion groups and forums (http://network.nature.com/). It started life in February 2007 ‘as an experiment in using social media for science’ (Nature.com, 2013) from the Nature Publishing Group, responsible, among others, for the prestigious scientific journal Nature. In May 2010 the network was relaunched with the inclusion of new features such as a Q&A section and a Workbench. Its activity ceased in 2013, although the information on groups, forums and users is today accessible, having become a ‘community archive’ (Nature.com, 2013). The reason for its closure was not at all clear, although those responsible argued that it did not provide the level of service expected by the users.

2.1.1 A Wide Range of Contacting Tools

Nature Network presented several communication instruments at different levels. At the group level, the most relevant were Forums, Groups and Questions & Answers because they were meeting points where users could interact with each other and share information. Other services such as Blogs and the Workbench were addressed to the creativity of the users and their ability to spread information and contents. Otherwise, the Hub was the main instrument for connecting the network to real life though events and meetings.

2.1.1.1 Forums

Nature Network provided tools for establishing specialized forums where users could discuss issues and controversies on scientific advances. It contained 1,822 forums where 16,678 discussion topics were laid out. It is interesting to observe that three of the five most populated forums were promoted directly by the creators of the site themselves (i.e. Nature India, Ask the Nature Editor and Careers Advice by NatureJobs), which provides evidence of little incentive among this community to create its own active and dynamic forums. In general, the activity in these forums was quite low, with less than one (0.3) message per person and a participation rate of only 2.5 per cent of the Nature Network community (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1

The five most active forums in Nature Network

| Name | Members | Topics | Replies | Messages | Activity |

| Brain Physiology, Cognition and Consciousness | 606 | 229 | 3,542 | 3,771 | 6.2 |

| Nature India | 1,386 | 1,336 | 2,296 | 3,632 | 2.6 |

| Ask the Nature Editor | 797 | 991 | 501 | 1,492 | 1.9 |

| PhD Students | 1,125 | 848 | 457 | 1,305 | 1.2 |

| Careers Advice by NatureJobs | 771 | 930 | 302 | 1,232 | 1.6 |

| Total | 27,012 | 16,678 | 16,909 | 24,621 | 0.9 |

| Average | 15.6 | 4.5 | 9.9 | 14.4 | 0.3 |

Figure 2.1 shows the number of forums that posted their last message by year. In general, the distribution describes low activity, with a large proportion (66 per cent) of forums without messages two years before the closure. The linear trend of the cumulative distribution and the constant number of forums by year confirm that this application remained inactive.

2.1.1.2 Groups

This platform helped the creation of specialized groups in which the members were able to share papers, opinions and news on their research disciplines. With the exception of the sharing of documents, groups technically worked as forums. In fact, participation in groups and forums was achieved through the same communication tools (topics and replies). However, this functionality was even less successful than in the forums – 188 different groups from psychology to scientific publishing were created (see Table 2.2), but the activity observed evidenced a low performance. Only an insignificant number of users (0.23 per cent) participated in these groups, with an average of 14.8 members per group. With the exception of Brain Physiology, Cognition and Consciousness (6.1), the rest of the groups presented less than one post per person.

Table 2.2

The five most active groups in Nature Network

| Group | Members | Topics | Replies | Messages | Activity |

| Brain Physiology, Cognition and Consciousness | 606 | 156 | 3,542 | 3,698 | 6.1 |

| National Institutes of Health | 275 | 13 | 12 | 25 | 0.1 |

| NPG Libraries | 157 | 43 | 53 | 96 | 0.6 |

| GSAS Harvard Biotech Club | 82 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 0.1 |

| Science Commons | 80 | 6 | 7 | 13 | 0.2 |

| Total | 2,792 | 501 | 3,761 | 4,262 | 1.5 |

| Average | 14.8 | 2.7 | 20.0 | 22.7 | 1.5 |

2.1.1.3 Hubs

Nature Network had three hubs or seats in Boston, New York and London. Each location maintained bloggers, offered scholarly job vacancies and promoted social activities that were intended to give the virtual network to the physical world. The most active node was London with 71 topics and 156 replies, followed by New York with 55 topics and 235 replies and Boston with 44 topics and 35 replies. As in the case of groups and forums, the activities promoted by these hubs had scarce incidence in the community as only a small number of members replied.

2.1.1.4 Blogs

One of the most interesting features was that each user had the opportunity to build a personal blog into the platform. These enabled the diffusion of scholarly reflections and scientific news. The number of blogs that arose from Nature Network is unknown, but many were moved to SciLogs.com when the network closed. More than 25 blogs were moved to this new platform (Infotoday.com, 2012), but still a very low number for the total amount of users (approximately 1.3 million). In spite of this, it is commendable that this service was offered to the users because it encouraged the publishing spirit in their members to disclose scientific results. In fact, many of these blogs continued to work on the new platform without problem. Moreover, Nature’s editors also developed personal blogs – 17 in total – that are still working on the Nature.com blog site.

2.1.1.5 Questions & Answers

The Questions & Answers (Q&A) section, added in 2010, allowed users to resolve any scientific question with the help of the online community (Nature.com, 2010). These answers were public and could be rated by the members according to their pertinence. The users that achieved better rates in their replies might be selected as Experts. Each profile would be able to manage the list of questions launched to the community as well as the questions replied by the researcher him or herself. The questions could be sorted by time, rate and subject area. Unfortunately, all the information on this section was removed when the service closed in 2013, so it is not possible to track the number of questions launched or the rate of response.

2.1.1.6 Workbench

As with the Q&As, the Workbench was also released in 2010 (Nature Publishing Group, 2010). This original service enabled a customized view of the Nature Network by adding applications (widgets) that made it possible to search and share scientific information. These apps could be built on OpenSocial technology, allowing each user to develop their own gadgets and share them. For example, Nature Network developed some products such as tools for searching in Nature.com or inserting videos from the same site. It also promoted the use of APIs to design apps that needed data from other platforms such as Connotea.

2.1.2 The Natural Community

This last section is possibly the most important because it concerns the creation of a personal sketch in order to be able to participate in forums and groups. The main page talks of 25,000 colleagues but in December 2014 a crawling of the site estimated more than 1.3 million members. A sample of more than 800,000 profiles was obtained from that crawling, acquiring data on disciplines, organizations, countries, etc. This sample helps us to describe what kind of users shaped the Nature Network community. The first thing that attracts the attention was that most of the profiles do not include any information and only 32.1 per cent of the users filled the profiles with some data. For example, discipline is the section most filled out with 29.7 per cent, while group information is only presented in 1.6 per cent of profiles, affiliation in just 0.92 per cent, and sex and age in barely 0.5 per cent. This scant attention to filling out a personal profile is an example of the poor commitment of the users the site and it could be considered a qualitative measure of the success of these services.

In any case, although this information could be not representative of the 1.3 million Nature Network users, we could start from the hypothesis that users that include some information in their profiles would be motivated by a closer involvement with the site and a more active participation. In this way, data on disciplines, sex or age could describe the profiles of the most active users in Nature Network.

Table 2.3 shows the most frequent research disciplines in the Nature Network’s profiles. Nature Publishing Group uses its own subject matter classification with which it arranges the content of its products. It is surprising that Business/Investment is the most frequent class with more than the 93 per cent of profiles. This could be due to some failure of assignation of that discipline and it is possible that it was added automatically by error. If that discipline is put to one side, Other (2.56 per cent) and Biology (1.65 per cent) are the disciplines that have the largest proportion of users in the system. Apart from Business/Investment, the distribution does not show any thematic bias and fits the common subject-matter distribution of large bibliographic databases (e.g. Web of Sciences, Scopus), although the elevated presence of Other could be a symptom of mis-classification or that the research activity of the users did not fit with that classification scheme.

Table 2.3

Distribution of profiles by research area in Nature Network

| Research areas | Profiles | % |

| Business/Investment | 229,713 | 93.18 |

| Other | 6,318 | 2.56 |

| Biology | 4,066 | 1.65 |

| Engineering | 1,782 | 0.72 |

| Chemistry | 1,291 | 0.52 |

| Medicine | 1,263 | 0.51 |

| Astronomy and Planetary Science | 808 | 0.33 |

| Earth and Environmental Science | 769 | 0.31 |

| Physics | 504 | 0.20 |

| Materials Science | 3 | 0.00 |

| Total | 246,517 | 100 |

By gender, Nature Network’s population presents a high percentage of men (67.9 per cent) in contrast to the 32 per cent of women. This percentage is similar (30 per cent) to the percentage of women in science (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2015) which demonstrates that the participation in this network is the same for men and women. With regard to age, the average of age is 32.8 years old, which suggests that most of the users are young scholars at the start of their academic career.

Table 2.4 includes the five organizations with more profiles on the site. Universities prevail in the ranking, with Harvard University (2.64 per cent), Imperial College London (1.39 per cent) and Columbia University (1.38 per cent) outstanding. It should be pointed out that two of the universities with the most profiles come from United Kingdom, which evidences the strong presence of British users in the network. It is also surprising that the fifth organization by number of profiles is the Nature Publishing Group (1.14 per cent). This could be evidence of the strong support of the owner company for this platform, although it would also report an excessive intervention of this publishing group in energising the network.

Table 2.4

Distribution of profiles by affiliation in Nature Network

| Organization | Profiles | % |

| Harvard University | 201 | 2.64 |

| Imperial College London | 106 | 1.39 |

| Columbia University | 105 | 1.38 |

| University College London | 100 | 1.31 |

| Nature Publishing Group | 87 | 1.14 |

| Total | 7,614 | 100 |

Table 2.5 ranks the ten countries with the most users signed into Nature Network. The United States (32.2 per cent) and the United Kingdom (15.2 per cent) are the countries with the largest presence, followed by India (11.4 per cent) and Germany (3.7 per cent). On examination of the penetration index, the United Kingdom (4.1 per cent) and India (4 per cent) are the countries where this platform yielded the most success. This penetration is not surprising in the United Kingdom because the head office of the Nature Publishing Group is located in London (NPG, 2015). Perhaps more remarkable is the penetration in India, which could de due to influence of United Kingdom and the Anglo world as other commonwealth countries such as Australia (0.15 per cent) and Canada (0.13 per cent) show high penetrations as well. In any case, these results are not entirely representative of the total population in Nature Network and so may only be considered from an illustrative point of view. According to its distribution across countries, Country Spreading (CS) index shows that 74 per cent of users belong to the first ten countries, which suggests that the platform did not go beyond the British environment.

Table 2.5

Distribution of profiles by country in Nature Network

| Country | Profiles | % | Penetration |

| United States | 2,454 | 32.23 | 1.74 |

| United Kingdom | 1,156 | 15.18 | 4.08 |

| India* | 871 | 11.44 | 4.01 |

| Germany | 285 | 3.74 | 0.75 |

| Canada | 212 | 2.78 | 1.19 |

| China | 155 | 2.04 | 0.10 |

| Australia** | 139 | 1.83 | 1.33 |

| Italy | 125 | 1.64 | 1.04 |

| France | 113 | 1.48 | 0.40 |

| Spain | 91 | 1.20 | 0.62 |

| Total | 7,614 | 100 |

*2010

**2008

2.1.3 The Chatting Room

Nature Network was one of the first online social networks for scientists that permitted the building of personal and complete profiles as well as incorporating two fundamental communication tools (Forums and Groups) that made possible the interaction between users. These communication instruments can be considered group tools, that is applications that promote the interaction among users at the same time and in the same place. However, although these instruments were created with the purpose of building a large and cohesive community, the reality was that most of the users were not so much interested in those functions. Results from the crawler verified this fact. The participation degree in these services was quite low, with only 2.5 per cent of users involved in Forums and 0.2 per cent in Groups. If the activity inside these services is observed, data show poorer values with an average activity of 0.3 posted messages in Forums and 1.5 in Groups. The other instrument, the Blog service, only produced 25 logbooks. These figures are clear symptoms that the network did not come up to the expectations of the users and could provide the most decisive proof of the failure of this site. It is possible to reinforce this claim because, as a result of the low amount of information used to describe the profiles, only 32.1 per cent of them included any data.

One other cause that would explain the closing of the site was that the presence of the Nature Publishing Group in the network was evident at all times. Most of the active forums and groups were created and propelled by Nature staff which suggests that the company did indeed exercise a strong intervention in the network. Since most of the blogs were also published by members of Nature, a monitoring policy of the site was instituted aimed at fostering a community of loyal ‘customers’ interested in Nature products. However, it is also possible that this excessive intervention was caused by the low participation of its members, and in consequence the company was looking to somehow keep the site active. Perhaps the last version introduced in 2010 incorporating the Workbench and Q&As could be understood as one final effort to stimulate the service. But the inactivity of the Forums and Groups sections and the scant information in the profiles decided in advance the eventual fate of the site.

In general terms, the Nature Network was the first initiative to pave the way to academic social sites with the sharing of information tools and personal profiles. However, it failed to create a comfortable environment that was attractive to the academic community. The model was closer to a chat room, in which direct communication between users in a public environment took precedence. Nature thus understood that a social network is just a public forum where research topics are discussed, recent publications are commented on and scientific news is spread. Nevertheless, any consistent virtual community should be based on the ability to produce and generate content which could then be shared, favouring networking and collaboration between its members.

2.2 BiomedExperts

BiomedExperts was an initiative for creating an online community of experts in biomedicine and related sciences. It was produced by Collexis Holdings in 2006, an American leader in semantic search and knowledge discovery software. In 2010, the technology of the site was acquired by Elsevier. The platform was finally switched off in December 2014, being integrated into Mendeley, a bibliographic references-based social community linked to Elsevier. However, the technology is currently being used in Pure (before SciVal Expert), a commercial platform from Elsevier to design scientific information services for research organizations.

2.2.1 Scientist’s Directory

Unlike other social services, BiomedExperts opted for automatically creating profiles as the starting point, thus counting on an initial population of profiles that gave consistency to the project. A key point in the success of an online social network is to have an important critical mass which allows its users to interact. As a specialized network in biomedicine, it started by creating 1.8 million ‘knowledge profiles’ from authors listed in about 18 million articles accessible through the PubMed database (BiomedExperts.com, 2011), the most important database on medicine. Only articles published during the previous ten years were selected to create profiles of active authors at that time. The authors of these profiles were then invited to participate in the network, edit their profiles more deeply and create new ties between their partners. However, BiomedExperts put up a number of restrictions when it came to creating a profile. Only users with a paper indexed in Pubmed within the previous ten years could create a full personal profile. Other users could simply browse the network of experts, but without any type of participation (BiomedExperts.com, 2010). This meant that the range of possible users was limited and most of them could only glance at the database.

The automatic creation of profiles of the authors of papers on the one hand produced duplicated profiles (i.e. distinctly different profiles corresponding to the same person) and on the other resulted in the merging of different authors with similar names. This is because researchers can author a research paper using different variations of their name. This problem is usual in academic bibliographic databases (e.g. Scopus, Microsoft Academic Search) and provokes inconsistency and noise (Ortega, 2014). In the case of social networks, it can cause mistrust and low performance. In BiomedExperts, each profile was disambiguated by identifying the ‘fingerprints’ of each author in keywords, places of work and age (Oswald, 2009) when it could not help but find duplicate and erroneous profiles.

However, in October 2014 there were only 473,000 profiles ‘validated’ by their respective authors (26.1 per cent), which informs us that interest from the research community was not very enthusiastic because only a quarter of the profiles were validated during the six years it had been running. To build the network, profiles were connected through bibliographical information, co-authors and research interests (Regazzi, 2013). In this way, any user could browse the network, jumping from one profile to another through any element the profiles had in common.

2.2.2 Interaction Tools

BiomedExperts, as a specialized directory of scientists, did not display any collaboration tools. Instead, it offered only a reduced range of communication tools. These could be divided into contacting devices at the profile level and instruments to assess articles. Thus each profile could only send internal messages to other members, bookmark researchers and add contacts to follow their updates and new publications. This reduced range of contacting tools limited the possibilities of user interaction, reinforcing the assumption that BiomedExperts was a scientific directory in which it was only possible to locate experts in specific fields and identify potential collaborators. In addition to this interaction function, there were other external tools that connected the network with other social sites. Thus it was possible to recommend a paper, profile or any other element through Twitter, Facebook, Connotea, etc.

At the publication level, it was possible to assess a paper (Congratulate), add it to a reading list or recommend it to other users. These mechanisms enabled the quality of a research paper to be evaluated, introducing impact elements into the publication list of a user. However, these instruments were limited to the publication list of a profile which could only gather articles from Pubmed.

2.2.3 Structure

As seen elsewhere, a user could only search partners and manage his or her own profile. The structure of the site was rather simple – just a display of a profile page from where other colleagues may be found and information on the user may be added. There were eight sections from the viewpoint of each user:

![]() Home. This part was devoted to the creation and management of the user’s own profile.

Home. This part was devoted to the creation and management of the user’s own profile.

![]() Contacts. This section listed the contacts added by each researcher and acted as an address book.

Contacts. This section listed the contacts added by each researcher and acted as an address book.

![]() Messages. This service made it possible to send internal mails to other profiles in the network.

Messages. This service made it possible to send internal mails to other profiles in the network.

![]() Recent publications. The most recent publications of a profile were included in this part. Note that BiomedExperts only included publications from Pubmed.

Recent publications. The most recent publications of a profile were included in this part. Note that BiomedExperts only included publications from Pubmed.

![]() Reading list. As a type of bookmark, this page included the articles authored by other profiles in the network, each having been selected as relevant or interesting for further study. The reading of these papers was possible if the user subscribed to the journal.

Reading list. As a type of bookmark, this page included the articles authored by other profiles in the network, each having been selected as relevant or interesting for further study. The reading of these papers was possible if the user subscribed to the journal.

![]() Find organization. This element helped the search for organizations under which profiles were affiliated. It allows searching by name, keywords and places.

Find organization. This element helped the search for organizations under which profiles were affiliated. It allows searching by name, keywords and places.

![]() Find researcher. As in the previous service, this section also included a search mechanism to retrieve profiles in BiomedExperts.

Find researcher. As in the previous service, this section also included a search mechanism to retrieve profiles in BiomedExperts.

![]() Conferences. This last service showed conferences and events that might be of interest to the profile, with information on country, dates and deadlines.

Conferences. This last service showed conferences and events that might be of interest to the profile, with information on country, dates and deadlines.

2.2.4 Pre-elaborated Profiles

As said above, at the moment of closure it was claimed there were 473,000 profiles, far from the 1.8 million automatically pre-elaborated profiles. Using the WayBack Machine of Archive.org, it was possible to track the evolution of the number of validated profiles since 2010. Unfortunately, previous years did not offer information on this element.

Figure 2.2 presents the evolution in number of validated profiles for BiomedExperts since 2010, the first year in which that information is displayed in the home page, counting 258,000 users already registered. The distribution clearly describes a pattern of descent from 2011, the moment at which most users claimed their profiles. The annual growth rate is the lowest of the social sites analysed with an increase of 10.6 per cent each year. These results make clear the lack of success enjoyed by this platform with a constant reduction in new active users from 2011, three years following its creation.

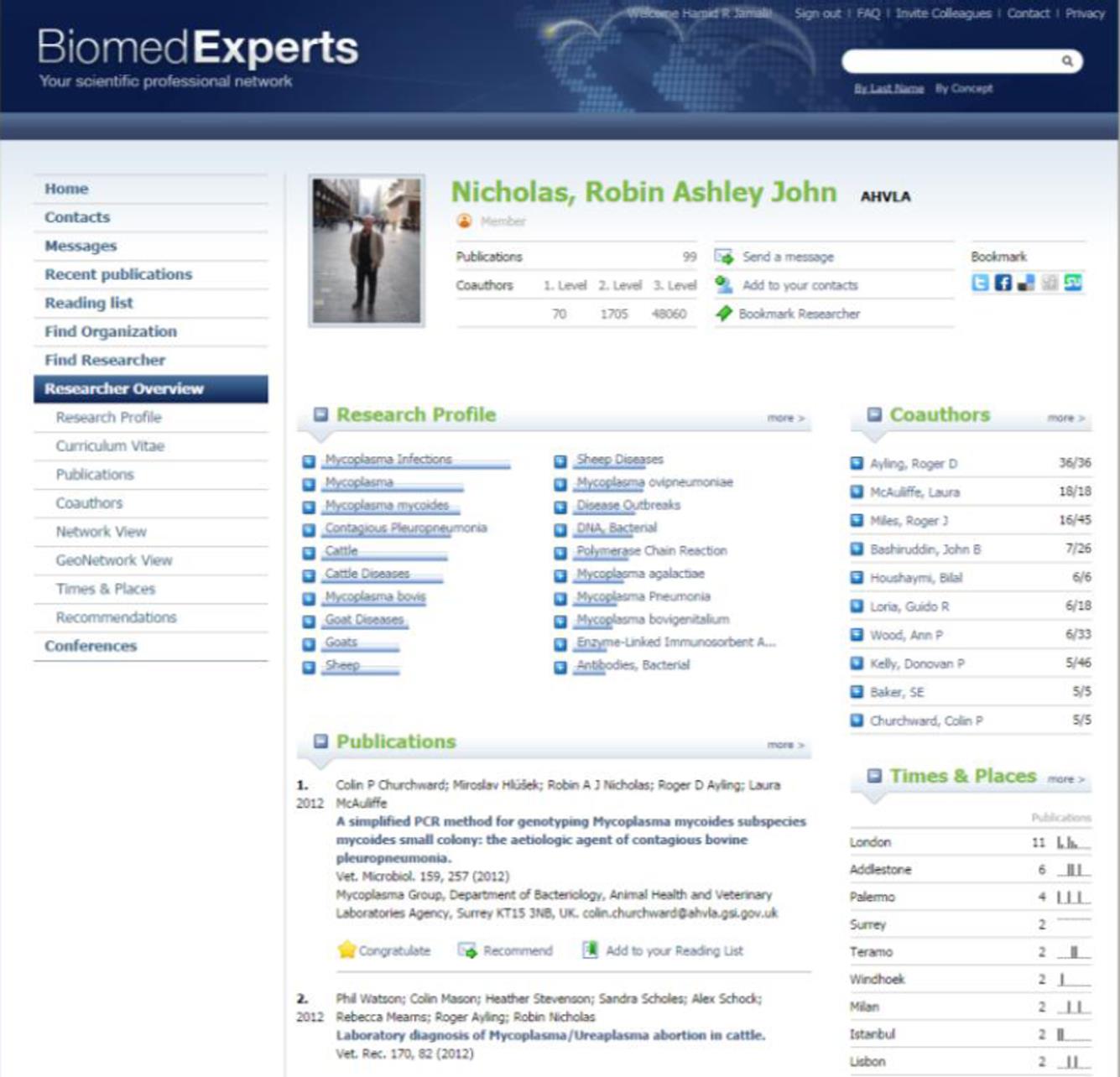

Each profile (Researcher Overview) included a name and research topics (Figure 2.3). The only quantitative data were the number of publications and the members included in their personal network, detailing contacts at the first (Co-authors), second and third levels. Next, it presented the only networking functionalities on this site: send a message, add a contact and bookmark a profile. Below, there were six elements that gathered together the academic information on the profile:

![]() Profile. This section contained an exhaustive list of keywords that described the research topics of each author. These terms were extracted from the papers and came in turn from MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), the National Library of Medicine controlled vocabulary thesaurus used for indexing articles for PubMed. Behind each word, a bar described the frequency of profiles that included that term, providing a way to explore related researchers within that topic.

Profile. This section contained an exhaustive list of keywords that described the research topics of each author. These terms were extracted from the papers and came in turn from MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), the National Library of Medicine controlled vocabulary thesaurus used for indexing articles for PubMed. Behind each word, a bar described the frequency of profiles that included that term, providing a way to explore related researchers within that topic.

![]() Publications. This part listed the publications of each profile extracted from PubMed and sorted by publication date. BiomedExperts did not allow the management of those publications, so it was not possible to add or remove papers wrongly assigned by the system. Another problem was that it was not possible to add papers not indexed by PubMed. Each reference links to an article page which contained the abstract and MeSH terms.

Publications. This part listed the publications of each profile extracted from PubMed and sorted by publication date. BiomedExperts did not allow the management of those publications, so it was not possible to add or remove papers wrongly assigned by the system. Another problem was that it was not possible to add papers not indexed by PubMed. Each reference links to an article page which contained the abstract and MeSH terms.

![]() Co-authors. This tab contained the list of co-authors with one profile in BiomedExperts sorted by number of co-authored publications.

Co-authors. This tab contained the list of co-authors with one profile in BiomedExperts sorted by number of co-authored publications.

![]() NetworkView. The last three sections corresponded to different visualizations of the co-author network. NetworkView graphed a circular ego-network with the first (co-authors) and second level of contacts. Several bars made it possible to refine the graph selecting the authors that most often collaborated (Co-publications) with the profile, most papers published (Publications) or most links had with other partners (Connections). On the right-hand side of the picture a full list of nodes was provided. The size of each name was proportional to the degree of collaboration. By clicking on each node, a short résumé of the profile was displayed.

NetworkView. The last three sections corresponded to different visualizations of the co-author network. NetworkView graphed a circular ego-network with the first (co-authors) and second level of contacts. Several bars made it possible to refine the graph selecting the authors that most often collaborated (Co-publications) with the profile, most papers published (Publications) or most links had with other partners (Connections). On the right-hand side of the picture a full list of nodes was provided. The size of each name was proportional to the degree of collaboration. By clicking on each node, a short résumé of the profile was displayed.

![]() GeoNetworkView. This view showed the same co-author network but this time on a geographical map where each node was situated on a workplace. Red dots represented the workplace of the author, green the workplaces of the co-authors.

GeoNetworkView. This view showed the same co-author network but this time on a geographical map where each node was situated on a workplace. Red dots represented the workplace of the author, green the workplaces of the co-authors.

![]() Times & Places. This section described the cities in which their papers were published.

Times & Places. This section described the cities in which their papers were published.

2.2.5 UniPHY: The Physics Sequel

Following in footsteps of BiomedExperts, in 2009 Collexis launched a similar product specializing in Physics for the American Physics Institute (AIP). UniPHY reproduced the same architecture as its big brother, creating a pre-elaborated population of 180,000 (300,000 in 2011) profiles from articles and papers published in 100 leading physics journals from Searchable Physics Information Notices (SPIN) in the previous 30 years as well as approximately 100,000 papers from scientific conferences (Seybold, 2009). However, its life was more ephemeral than its predecessor and it was closed in 2012.

2.2.6 A Static Network of Automatic Profiles

BiomedExperts and its younger brother UniPHY presented a particular strategy for creating an online community based on automatic profiles that were later claimed by their authors. In this way, Collexis could quickly generate specialized networks of researchers extracting authors from a large repository of scientific articles. These products were improved by means of a good semantic classification system that categorized each profile through relevant keywords. But, above all, the success of these social sites was due to their impressive visualization which became the key instrument for exploring profiles in the system.

However, while the collaborative relationships expressed in scholarly papers were the ties to build those networks, they were not the links that profiles established with other colleagues using contacting tools. BiomedExperts and UniPHY could not be considered online social networks because their architecture was not supported by the interaction of their users, but in the co-authorship network shaped outside the website. Although it is true that these platforms included contacting tools (adding a contact, bookmarking a researcher, etc.), these instruments were oriented to establishing further contacts through other media, not in the platform itself. In this form, Collexis’ products were merely expert databases focused only on browsing and locating scholars, instead of platforms where the knowledge and expertise could be shared by the online community in the same place. This model produced passive profiles that were only used to show the research production of their users, more so if we take into account that two-thirds of the profiles were not edited by their authors. This model ended up as a static yearbook where the users were considered passive subjects that only showed their papers so they could be selected as partners.

A further factor that provided evidence that these products were not oriented to social networking was that the population of profiles was not only limited to disciplines, but to specific bibliographic sources such Pubmed in BiomedExperts and SPIN in UniPHY. This restrictive policy blocked the growth with new profiles and limited the publications that users could offer. To this may be added that these platforms were designed as isolated and specialized islands that did not represent the interdisciplinary nature of science. Perhaps this would explain why only one-third of their profiles were claimed in BiomedExperts.

In summary, the cause of the collapse of the Collexis model could be explained by a wrong understanding of the academic social networks, where users need a medium to share things, going beyond contact among them. This ignorance is also reflected in the restrictive conditions surrounding opening a profile, which meant a large proportion of researchers were not able to participate in the site.

2.3 Why did these Sites Fail?

Nature Network and BiomedExperts were the two most outstanding initiatives of social networks for scholars. Both sites expected to build an online community from different approaches. In Nature Network, the engagement of the users with the system was established through groups and forums, the two principal social environments of the site. On the contrary, BiomedExperts and UniPHY were directories of scientists in which the interaction was channelled thought internal messages and follow-up contacts. This meant that some sites presented corseted structures that only permitted certain actions, making it hard for their users to develop a different activity than that pre-established by the system.

These limitations meant that these sites were characterized by an important interventionist attitude by the site creator, which directed user actions in specific directions. In the case of Nature Network, the most active groups, forums and blogs were those that were created by journalists and media professionals within the company. Perhaps this was an attempt to move the network and breathe new life into the project, though it could also generate a certain sense of control by part of Nature Publishing Group. Put another way, Collexis’ products were closed environments in which even the profiles were automatically elaborated by the system. In addition, they had important restrictions on access, because only authors indexed in important databases such as Pubmed (BiomedExperts) and SPIN (UniPHY) could participate in the network. In this sense, while the service met the expectations of the owner in the creation of a directory of experts, it did not fulfil the desires of its users for sharing and generating content.

It is possible to think that this lack of flexibility in the architecture of these media was the cause of their inability to adjust to the users’ requirements, gradually forcing the abandonment of these platforms. As has seen above, one of the critical elements in a social networking site is the possibility of producing content by the users themselves. In Nature Network, users could only share ideas and news by means of forums and groups, but they could not produce any content. One exception was the creation of a blog, but this tool required a great effort and only a very small number implemented this functionality successfully. In the case of Collexis’ products, they did not even allow the addition of publications to the profile, much less initiate any discussion with other users.

In view of this inability to create content, these systems neither offered any metric that enabled the performance of a profile to be tracked nor made any action on the site possible. Thus users were not able to observe whether their actions or profiles were seen by other members. For example, Nature Network did not offer any information on visits to the profiles, nor even a rating of the responses in groups and forums. BiomedExperts only permitted congratulations on an article but without any account of the rewards. These restrictions brought about a lack of interest among users as the system did not pass on the impact or importance that these actions had for other users.

However, in spite of these important limitations which were the cause of the slow decline and later closure of these platforms, they were the first to introduce the idea of specialized social network sites for scholars. Today, it is inconceivable to think of an academic social site without a discussion space where scientific subjects are debated, or platforms without profiles that boost their publications and are connected through co-authors, interests or organizations. Both services contributed to laying the foundations for Science 2.0 and social networking in Science. As will later be seen, many of the current platforms owe a large debt to these pioneer sites.