Business Rule Models

Business rules are the fourth and last business modeling discipline described in this book. Business rules shape the behavior of a business and guide the behavior of the business’s employees. Business rules explain what is allowed and what is not allowed. A business rule model also explains the consequences of violation: what happens when a rule is violated. This chapter describes business rule models.

Sometimes customers at a Mykonos restaurant leave before they finish their dinner. Perhaps there is an emergency at home, and they must leave to tend to the emergency. Or someone in the party became ill while they’re at the restaurant. Or they were disgruntled, unhappy with the wait for their dinner, and leave before their dinner arrives.

There are many legitimate reasons for a restaurant party to leave early. There is also one illegitimate reason: Like all restaurants, Mykonos occasionally suffers from dine-and-dash, a form of theft where a restaurant party leaves early without paying, effectively stealing the restaurant meal.

What should a Mykonos server do if one of her parties leaves early? Should the party have to pay for their dinner? What if the service truly was bad or if the waits truly were long? And how should Mykonos separate customers who legitimately must leave early from those who would dine-and-dash?

There are additional issues around customer payment. Maybe the customers are surprised by the size of their bill, and question one or more of the charges. The server needs to resolve the situation, and if she cannot, the manager will attempt to do so.

And sometimes, a customer is willing but unable to pay. None of his credit cards have enough credit. Or he’s left his wallet behind at home. What happens now?

Mykonos Dining Corporation provides instructions to their restaurant employees about what to do in these situations. These instructions are called business rules. The business rules guide the servers and managers when confronting payment situations. By providing business rules, Mykonos can take advantage of the shared experience of many people, to provide best-practice solutions to all employees.

Mykonos also provides business rules for other circumstances—circumstances that do not involve payments. There are business rules to protect the health of the Mykonos restaurant customers and to ensure that the local health codes are satisfied. There are business rules around safety, to ensure that no employees are hurt, especially since the restaurant business involves both fire and knives. There are business rules around staffing and scheduling employees, to promote both fairness and efficiency and to reduce employee dissatisfaction. There are business rules about seating customers at tables and managing customers that are waiting to be seated. And even though menu design for a restaurant is largely left to the discretion of the restaurant head chef, there are some business rules about menu design—for example, to ensure that vegetarian customers always have at least two entrees from which to choose.

Business Rules Shape Behavior

What is a business rule? A business rule is “a directive intended to influence or guide business behavior” [Ross 2003]. As a directive, a business rule can be an order—“This must be done”—or a suggestion—“This should be considered”—or something between an order and a suggestion. The purpose of a business rule is to shape behavior: Do this and don’t do that. And the guidance is business guidance: For Mykonos there are business rules about payments and cleanliness and appropriate attire for customers but not about who an employee dates or what a customer does after he leaves the restaurant. Employee dating and customer behavior after they leave the premises are outside the scope of the restaurant business.

Consider a Mykonos business rule about payments:

Charging for Orders: It is obligatory that a party is charged for a menu item if the party orders the menu item and the menu item is served to the party.

Charging for Orders is a business rule. It is a directive: it says what must be done. If Joe orders a glass of pinot noir and the glass is served to him, his party must be charged for it. If the wine is served and Joe starts drinking it but leaves before he finishes, his party must still be charged. If the wine is served but the party later leaves because they are dissatisfied with the service, the wine must still be charged. The Charging for Orders business rule applies to all these situations.

But some situations are not covered by Charging for Orders. What if Joe orders a glass of pinot noir, but Joe and the rest of his party leave before the wine is served? Charging for Orders is silent on that situation; presumably other business rules apply. Similarly, if a glass of pinot noir is served to Joe’s party but neither Joe nor anyone else ordered it, Charging for Orders does not say whether it must be charged.

Business rules travel in groups. It is rare for a single business rule to exist by itself, without 5 or 20 others that apply to related situations. There are many other Mykonos business rules about payments. For example:

Splitting Bills: It is permitted that a server may split a bill only if the party agrees to bill splitting and the bill is split equally.

The Splitting Bills business rule provides guidance about bill splitting—the conditions under which it is permissible for customers to split a bill. There are two conditions that must be true if a bill is to be split. If the party does not agree to split the bill, the bill may not be split. And the bill may not be split if it is to be split 60–40 or anything other than equally.

Splitting Bills seems quite understandable, but only because we are relying on our existing knowledge about servers, parties, and restaurant bills—knowledge that we all have gained from eating in restaurants. Someone who has never eaten in a restaurant might wonder what these words really mean. If a person eats by himself, is that a party? What about 11 people who eat at two separate tables because there is no room to seat them all together? What is a bill, really? A complete business rule model that includes Splitting Bills needs to define some nouns: server, party, and bill. Charging for Orders also uses two nouns that need definitions: party and item. Is a glass of pinot noir an item? Is a cigar? A shoe?

There are some other mysteries about Charging for Orders and Splitting Bills—mysteries at least to our fictional person who has never enjoyed a restaurant meal. What does it mean for a party to incur a bill? Can a server incur a bill? Can a bill incur another bill? What does bill splitting mean? What does it mean for a bill to be split equally? A complete business rule model needs to define verbs like incur and concepts like equal splitting. Later in this chapter, we show how all these terms are defined as part of a business rule model.

Why No Diagrams?

You might have noticed that the business rules Charging for Orders and Splitting Bills are shown here as sentences in English, not as diagrams. The business motivation models in Chapter 3 were diagrams, as were the business organization models in Chapter 4 and the business process models in Chapter 5. Why are business rules textual when the models in the other three disciplines are graphical?

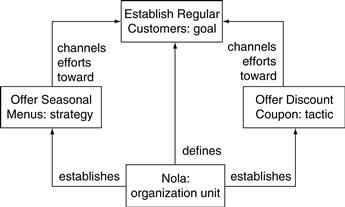

In fact, a business motivation model can be described in text instead of in a diagram. Consider the simple motivation model shown in Figure 6.1 (and originally presented as Figure 3.5). Figure 6.1 can be expressed textually instead of visually:

The organization unit Nola defines the goal Establish Regular Customers. Nola establishes a strategy Offer Seasonal Menu that channels efforts toward Establish Regular Customers. Nola also establishes a tactic Offer Discount Coupon that channels efforts toward Establish Regular Customers.

The text is equivalent to the diagram; from either you could create the other. In reviewing a business motivation model with a subject matter expert, it is often convenient to show him the diagram and walk him through it by saying the equivalent text so that he understands each element in the diagram. Diagrams are (usually) easier and faster for people to understand, so business motivation models are usually expressed graphically.

Business organizational models can also be expressed textually, in much the same way. So can business process models. Every model in this book can be expressed in English1 instead of in lines and boxes and other graphical elements. As with business motivation models, the usual practice is to express organization and process models graphically; as you’ve seen the resultant diagrams are easier and faster to understand than the equivalent words.

Business rules are different. Some experts have proposed graphical languages for business rules (e.g., Terry Halpin’s work [Halpin 2001]), but most people find the words easier to understand than the diagrams. In our experience, a business professional will more quickly understand a well-written business rule than she will understand a business process of equivalent complexity. Why? The reason is not clear. Perhaps our brains are just wired to comprehend rules. Perhaps in our ancestral past there were advantages to quickly learning tribal rules articulated by a tribal elder, and advantages to quickly recognizing when a rule was violated. Presumably the East African savannah offered no such advantages to the quick learning of business processes.

Even though business rules are in practice written as sentences instead of diagrams, they are still business models. Not all models are visual. With business rules, the model is expressed in the logic of the text rather than in a diagram.

A business rule is a model because it fits the definition we introduced in Chapter 1: it is a simple representation of a complex reality. For example, the Splitting Bills rule we examined earlier is simple guidance that applies to thousands of different restaurant situations, many of which are complex.

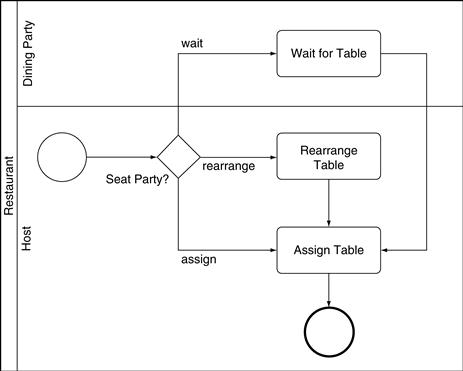

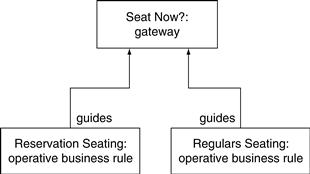

But there are some diagrams in this chapter. Although the business rules we examine are all shown as text, we do show diagrams of how those rules relate to other model elements, just as we showed diagrams in Chapter 5 of how activities relate to goals and to objectives. We also include some simple diagrams that show how rules are constructed, that show the components of a rule and the ordering of those components. And we include fact type diagrams. As we explain later in the chapter, fact types are verbs used in rules and the nouns those verbs tie together. Fact types lend themselves to diagrams. So although there are no diagrams of business rules themselves, this chapter has many diagrams for other purposes.

Why Business Rules?

Why model business rules? As you recall, there are eight purposes for business modeling in general. Of these eight, business rules can achieve six: communication, training and learning, managing compliance, software requirements, direct execution, and knowledge management. But one of these six is by far the most common. Today, when a business rule model is created, it is usually for the purpose of specifying requirements for application software. Business rules are not a traditional means for specifying software requirements, but they complement the traditional techniques by capturing something that those techniques do not. Business rules capture constraints on behavior. They capture what is allowed and (more important) what is not allowed.

Of course, writing software from requirements is always slow, since it involves people understanding requirements and using those requirements to write and test code. A faster approach for implementing business rules in software is emerging: business rules can be directly executed. Instead of a person reading the business rule and translating the rule to code, a software application reads the rule and directly applies the rule when appropriate. New rules can be added and existing rules changed, and these changes are effected immediately.

At least that’s the promise of direct execution. Today, direct execution is rare, since the technology is not widely understood. But in the future we expect direct execution to be widespread.

Business rules are used for communication—to communicate guidance to company employees. Business managers and proprietors guide employees about what to do and what not to do. Managers and proprietors have been crafting policies and other guidance for hundreds of years; one can imagine Benjamin Franklin writing lists of dos and don’ts for the employees of his printing businesses in the 18th century. But this managerial guidance has—until recently—been informal. There is little similarity from one company to another in the format and wording of their policies and guidance.

We are seeing some change here. Informal approaches to employee guidance famously suffer from misinterpretation. Joe and Jerry can interpret the same policy in different ways. Business rules offer precision, providing a way to guide employee behavior that avoids misinterpretations. So some companies are investigating the use of business rules for employee guidance.

Similarly, when a new recruit starts with a company, she must learn all the rules and policies of her new employer. She must learn all about “how we do things here.” A business rule model is a good way to capture those rules and policies so they can be easily understood. Business rules are useful for training and learning.

Regulatory compliance is more important now than it has ever been. New laws and regulations require changes to company behavior. These company behavior changes usually then require changes in the behavior of individual employees. When a new law takes effect, there are actions that employees are no longer allowed to perform. This translation from a legal change to an employee behavior change is the path by which compliance is implemented.

Business rule models support compliance implementation, and support it easily and gracefully. When new regulation occurs, the regulation is analyzed for its impact on the business rules. Then new rules and changed rules are published so that employees are aware, and change their behavior. Sometimes applications must also change to support new regulatory requirements. If the applications are tied to business rules through a manual requirements process, the new rules and changed rules identify the components of the application that must change. Alternatively, if the applications directly implement the business rules, the new rules and changed rules are directly executed and the change occurs.

Business rules support knowledge management. Business rules are a good form for capturing much of the tacit knowledge that organizations want to preserve.

Rules

Let’s consider some simple rules about customer payments, to better understand how business rules work and the forms they can take.

Greenbacks Only: It is obligatory that each cash payment employ US currency.

Like all business rules, Greenbacks Only shapes behavior. It says what should occur. The Mykonos restaurants accept payments in cash, but only greenbacks can be used. No euros or yen are accepted.

No Checks: It is prohibited that a payment employ a personal check.

No Checks says what should not occur. Mykonos restaurants do not accept any personal checks for payments.

VISA Only: It is permitted that a payment employ a credit card only if the credit card is backed by VISA™.

VISA Only says what is allowed and the conditions under which it is allowed.

These three business rules illustrate three forms. The guidance captured by a business rule says what should be—it is obligatory that; what should not be—it is prohibited that; or what is allowable and the conditions under which it is allowed—it is permitted that … only if.

These three business rules sound absolute. No exceptions will be brooked and any server who accepts payments in euros will be fired on the spot. But in truth Greenbacks Only says absolutely nothing about whether it is strictly enforced with severe penalties or whether it is merely a recommendation, to be followed at the server’s discretion. The same rule is written the same way in either case. Similarly, No Checks might be as strict as it sounds, or it might be merely a recommendation for individual behavior, or it could be somewhere in between.

Later in the chapter we describe level of enforcement, the degree to which a rule is actually enforced by an organization. But for now, just note that the level of enforcement is separate from the rule itself; that a rule is written in the same absolute way whether it is to be strictly enforced or merely a guideline.

Just as a business rule does not say to what degree it is to be enforced, it also doesn’t say who does the enforcement. Greenbacks Only is silent about who tells the customer that only US cash can be used. Maybe it is enforced by the server, maybe by the restaurant manager. The rule can also be used by the restaurant host—for example, if a prospective customer calls and asks whether euros are accepted. In a similar way, VISA Only is silent about who enforces the guidance that only VISA cards are accepted.

Some rules are automatable. They can be enforced by an application or perhaps by several applications. For example, in addition to being enforced by a server or a manager, VISA Only could be enforced by the payments application. When an American Express™ card is swiped, the application rejects the attempt, perhaps showing a dialog box that displays the rule “It is permitted that a payment employ a credit card only if the credit card is backed by VISA.” The rule is the same, regardless of whether it is enforced by people or machines.

Business rules change. For example, Mykonos restaurants might start accepting MasterCard™ and American Express. If they do, VISA Only must be changed to reflect the new cards accepted.

Credit Cards Accepted: It is permitted that a payment employ a credit card only if the credit card is backed by VISA or the credit card is backed by MasterCard or the credit card is backed by American Express.

Business rules change more often than other business models. In an organization as large as Mykonos, every week will see at least one rule changed or added. Sometimes things will change even more quickly. Discover™ cards will become accepted on Monday, a new safety policy to prevent customer falls will start on Tuesday, a new rule around scheduling servers will be implemented on Wednesday. This is a much faster pace of change than that of business processes, business organizations, or business motivations. Business organizations and business motivations typically change far more slowly, with a few changes each year instead of a few changes each week.

Business Rule Forms

Some of the business rule examples in this chapter have started with the phrase “It is obligatory that” and then continued with a statement of what is obligatory. These business rules use the same “It is obligatory that” form. There are six business rule forms, one of which uses the phrase “It is obligatory that.” We will describe each of the six, giving examples of business rules for each.

Obligation Statements

Many business rules oblige people (or software applications) to ensure that something is true. These truth-ensuring rules are obligation statements. An obligation statement begins with the phrase “It is obligatory that” and then continues with what is demanded.

Earlier we considered Greenbacks Only, a simple obligation statement.

Greenbacks Only: It is obligatory that each cash payment employ US currency.

As an obligation statement, Greenbacks Only implicitly acknowledges the possibility that a customer might attempt to use another currency. For example, a customer might think he could pay his bill with euros. A server might accept the euros, either as a mistake or in ignorance or as a knowing violation of the rule. All this is possible, and in practice might happen. But as a company, Mykonos mandates that it must not happen. Greenbacks Only says that each Mykonos employee has an obligation as part of his or her job to accept only US dollars for cash payments. Further, each Mykonos employee has an obligation to inform customers of this restriction if there are questions or confusion.

Figure 6.2 shows the structure of a simple obligation statement such as Greenbacks Only. The expression that follows “It is obligatory that” is called the mandatory situation. In Greenbacks Only, the mandatory situation is “each cash payment employ US currency.” That mandatory situation itself may be either true or false. The mandatory situation is true if a cash payment in a Mykonos restaurant in fact employs US currency, and it is false if a cash payment in a Mykonos restaurant employs euros or yen or sterling. Greenbacks Only says nothing about whether the mandatory situation is true or false. Instead, Greenbacks Only states that the Mykonos employees have an obligation to make the mandatory situation an actuality.

Greenbacks Only is a simple obligation statement. Let’s consider a more complex variant of Greenbacks Only.

Greenbacks Only B: It is obligatory that each cash payment employ US currency if the payment amount of the cash payment is at least 20 dollars.

Greenbacks Only B insists on US currency for larger amounts but says nothing about what should happen for payments of less than $20. Either other rules apply for those smaller payments or a server is free to accept other currencies.

Like Greenbacks Only, Greenbacks Only B implicitly acknowledges the possibility of customers paying with more than $20 in non-US currency as well as the possibility of servers accepting such currency. But Greenbacks Only B indicates that such behavior must not happen.

Figure 6.3 shows the structure of Greenbacks Only B. Figure 6.3 includes an optional condition as well as the mandatory situation. The condition is the scope of when the mandatory situation actually applies—when it is mandatory. For example, in Greenbacks Only B, the condition is “the payment amount of the cash payment is at least 20 dollars.” If the condition is true—if the cash payment is at least 20 dollars—then the mandatory situation applies. For those payments the employees of Mykonos have the responsibility of ensuring that US currency is used. If the condition is false—if the cash payment is less than 20 dollars, nothing is mandated. The Mykonos employees are not obligated to do anything, at least nothing to satisfy this rule. The “if” in Greenbacks Only B effectively reduces the concern to just those payments where the condition is true—just those payments that are $20 or larger.

Greenbacks Only B is not a good business rule because there are situations in which it is not clear whether the rule applies. Suppose a customer pays ![]() 15 for a couple of drinks at the bar. Is this payment more than $20? How is a server to know, unless she carries the daily currency conversion rates with her? Greenbacks Only C is a better rule with the same intent.

15 for a couple of drinks at the bar. Is this payment more than $20? How is a server to know, unless she carries the daily currency conversion rates with her? Greenbacks Only C is a better rule with the same intent.

Greenbacks Only C: It is obligatory that each cash payment employ US currency if the cash payment is applied to a bill and the amount of the bill is at least 20 dollars.

Now a server need only know the amount of the bill to determine whether euros are allowable. Of course, if the payment is accepted, someone will have to make a calculation of whether ![]() 15 is a sufficient payment and what the change should be. Other rules apply.

15 is a sufficient payment and what the change should be. Other rules apply.

Greenbacks Only B and Greenbacks Only C have the same mandatory situation: “each cash payment employ US currency.” But the conditions of the two rules are different. The condition of Greenbacks Only C is “the cash payment is applied to a bill and the amount of the bill is at least 20 dollars.” Where the condition is true, the employees of Mykonos have the responsibility of ensuring the mandatory situation—of ensuring that cash payments employ US currency. No obligation results where the condition is false. For example, if the account of a bill is less than $20, it does not matter whether US currency is used. Similarly, a cash payment that is applied to something else (other than the bill) can also be done in a non-US currency. A customer might pay greenbacks for his bill, but leave a tip in Mexican pesos, knowing that the server is leaving the next day for a vacation on the Mayan peninsula. Such an action does not violate the rule because the action falls outside the scope of the condition. The rule is only violated when a cash payment is in non-US currency, it is applied to a bill, and the bill is large enough, at least $20.

Obligation statements are the most common of the business rules. When do you use an obligation statement? An obligation statement is used when you want the business—the employees and perhaps the software applications—to ensure that something is true. You first determine the expression that must be kept true, make it the mandatory situation, and (if necessary) create a condition that captures the scope of when the mandatory situation applies.

Prohibitive Statements

Some business rules are meant to prevent. These preventative business rules are called prohibitive statements. We have seen several prohibitive statements in this chapter (e.g., No Checks a few pages back). Let’s look at a prohibitive statement that is a variant of our obligation statement Greenbacks Only.

No Loonies: It is prohibited that a cash payment employ Canadian currency.

Instead of insisting that cash payments employ US currency, No Loonies insists that such payments do not employ Canadian currency. (Perhaps this rule is for a Mykonos restaurant in Buffalo, New York, in which customers often try to pay their bills in Canadian dollars instead of greenbacks.)

As with its obligation statement counterparts, No Loonies does not claim that there are no cash payments that use Canadian currency. Rather No Loonies states that Canadian currency should not be allowed for payments. Employees have a duty to reject cash payments in Canadian currency. Software applications such as payment applications should reject such payments as well.

The structure of No Loonies is shown in Figure 6.4.

A prohibitive statement starts with the phrase “It is prohibited that.” After that phrase is the banned situation, an expression of what must be false. The banned situation of No Loonies is that “a cash payment employ Canadian currency.” A prohibitive statement says that employees (and perhaps software applications) have a responsibility to prevent the banned situation. Employees can prevent the banned situation of No Loonies by rejecting cash payments in Canadian dollars and by advising customers that Canadian dollars are not accepted.

As with obligation statements, prohibitive statements can be more complex than No Loonies. Many prohibitive statements make the prohibition conditional on some other expression. Consider No Loonies B.

No Loonies B: It is prohibited that a cash payment employ Canadian currency if the cash payment is applied to a bill and the amount of the bill is at least 20 US dollars.

No Loonies B prohibits the use of Canadian currency for larger bills—those of more than 20 dollars. The structure of No Loonies B is shown in Figure 6.5. It includes a condition in addition to the banned situation. The condition is a scope of the ban, a description of when the ban must apply and when it need not.

The condition of No Loonies B is “the cash payment is applied to a bill and the amount of the bill is at least 20 dollars.” When the condition is true, the banned situation must be prevented. Employees and applications have a duty to examine the payment of bills of more than $20 to ensure that Canadian dollars are not used for those payments.

When do you write your intended business rule as a prohibitive statement? You use a prohibitive statement when you want the business—the employees and perhaps the applications—to prevent something. You write the banned situation—an expression that describes what must be prevented. If necessary, you write the condition—an expression of the scope of the ban.

Restricted Permissive Statements

Another business rule form is the restricted permissive statement. A restricted permissive statement specifically allows something but restricts the condition under which it is allowed. Let’s look at an example, a variant of the same cash payment rule.

Euros Allowed: It is permitted that a cash payment employ European Union currency only if the cash payment is applied to a bill and the amount of the bill is at most 100 U.S. dollars.

Two Mykonos restaurants are located close to embassies of EU countries. Many of the customers of those restaurants are foreign service officers and other members of the foreign embassy community. For the convenience of those customers, the two Mykonos restaurants accept euros. Euros Allowed says that euros can be used for bills that are $100 or less but that larger bills cannot employ euros. Euros Allowed is violated when a customer attempts to use euros to pay for a large bill, one of more than $100.

The structure of a restricted permissive statement is shown in Figure 6.6. The restricted permissive statement includes a permitted situation. The permitted situation describes what is allowed. In Euros Allowed, the permitted situation is “a cash payment employ European Union currency.” Mykonos allows the cash payment to employ EU currency. The restricted permissive statement also includes a restriction. The restriction describes the scope of the permission—what must be true for the permission to occur. The permitted situation is only allowed to be true if the restriction is also true. In Euros Allowed, the restriction is “the cash payment is applied to a bill and the amount of the bill is at most 100 dollars.” Mykonos allows a cash payment to employ euros only under the restriction that the cash payment is applied to a bill of $100 or less.

The condition in an obligation statement is optional. You can create an obligation statement that has no condition, and it is still a valid business rule. The condition in a prohibitive statement is also optional. But the restriction in a restricted permissive statement is required. Without a restriction, the restricted permission statement does not actually shape any behavior. Consider our example without a restriction: “It is permitted that a payment employ European Union currency”—euros are OK. But if the rule does not exist, then EU currency is OK anyway. Without a restriction, the rule does nothing.

What violates a restricted permissive statement? A violation occurs when the permitted situation is true even though the restriction is false. The other combinations do not matter. If the restriction is true, it doesn’t matter whether the permitted situation is true or false; no violation occurs. For example, if the amount of the bill is $57, the restriction is true, and it doesn’t matter (to this rule) whether European currency is used or not. Euros Allowed is not violated. And if the permitted situation is false, no violation occurs. If a cash payment does not use euros, it does not matter whether the bill is for $57 or $570. Euros Allowed remains not violated.

When do you write your business rule as a restricted permissive statement? You use a restricted permissive statement when you want the business to permit something only under certain conditions. You write the permitted situation first. Then you write the restriction—what must be true for the situation to be allowed.

Necessity Statements

We have considered three forms of business rules: obligation statements, prohibitive statements, and restricted permissive statements. These forms have different semantics, but they are similar in one respect. They all describe what should be. An obligation statement describes what a business should try to ensure. A prohibitive statement describes what a business should try to prevent. And a restrictive permissive statement describes what a business should allow under certain conditions.

But some business rules are not concerned with what should be. Instead they describe what is. Consider the business rule Single Payment Network.

Single Payment Network: It is necessary that a credit card is backed by exactly one payment network.

VISA is a payment network, as is MasterCard and American Express. Being backed by a single payment network is fundamental to the meaning of a credit card. That is exactly what a credit card does; it provides access to a payment network. Each card is back by exactly one payment network. Capital One may issue both VISA cards and MasterCards, but a single card is either one or the other. A VISA card provides no access to the MasterCard network, or vice versa: a MasterCard cannot access the VISA network.

Single Payment Network does not state what Mykonos employees or customers should do. Instead it states something that is always true; it states a general truth rather than a responsibility. No actions of a Mykonos employee or customer will violate Single Payment Network. In fact, only a major industry change—e.g., an inter-access agreement between payment networks—will affect Single Payment Network, and that major industry change will not violate the rule so much as render it entirely invalid.

Single Payment Network is a necessity statement. Each necessity statement is a statement of something that remains true. Some necessity statements express truths about the world, like Single Payment Network. Others express truths not about the world but about the way the organization defines the world. Large Party is an example of this latter situation.

Large Party: It is necessary that a party is large if the size of the party is at least 8.

A party of 8 or 9 people is considered by Mykonos restaurants to be large. A party of 6 or 7 is not considered to be large, at least not by Large Party. (Another rule may of course apply.) This division between 7 and 8 is how Mykonos chooses to structure its work. Other restaurants will divide party size differently, and some will not even have the concept of a large party.

The structure of a necessity statement is shown in Figure 6.7. A necessity statement starts with the phrase “It is necessary that.” A necessity statement includes an assured situation, the description of what is necessarily true. The assured situation of Large Party is “party is large” and the assured situation of Single Payment Network is “credit card is backed by exactly one payment network.” The necessity statement also includes the word “if” and a condition. The condition of Large Party is “the size of the party is at least 8.” As with obligation statements, the “if” and the condition are optional. For example, Single Payment Network has no condition.

A necessity statement is structurally a bit like an obligation statement. Both are about something positive. Just as an obligation statement states something that must be, a necessity statement states something that is always true. But the two forms of business rules are quite different in intent. An obligation statement expresses something that the organization mandates. A necessity statement is simply a statement of what is always true, either in the world or in the way the organization structures its knowledge about the world.

Necessity statements express structural business rules. Structural business rules are statements about what is. They cannot be violated and need not be enforced. Structural business rules are fundamentally different from operative business rules, those rules that state what should be. Obligation statements, prohibitive statements, and restricted permissive statements are all operative business rules. Operative business rules can be violated and must be enforced.

When do you write your business rule as a necessity statement? You use a necessity statement when some situation is always true by definition. You write the true-by-definition situation as the assured situation. If a condition applies, you add it.

Impossibility Statements

Necessity statements are not the only structural business rules. Impossibility statements are also structural business rules. Instead of stating what is always true, an impossibility statement states what is always false. For example, Single Payment Network B is an impossibility statement.

Single Payment Network B: It is impossible that a credit card is backed by two payment networks.

A single credit card cannot be backed by two different payment networks. For example, the same credit card cannot be both a VISA and a Discover.

The structure of Single Payment Network B is shown in Figure 6.8. The impossibility business rule starts with “It is impossible that” and then continues with the incorrect situation, the situation that is always false. For Single Payment Network B, the incorrect situation is “a credit card is backed by two payment network.”

More complex impossibility business rules are also possible. Consider Vegetarian Menu Items.

Vegetarian Menu Items: It is impossible that a vegetarian menu item includes an ingredient if the ingredient is meat or the ingredient is fish.

Vegetarian Menu Items is true by definition. A vegetarian menu item contains no ingredient that is meat or fish.

The structure of Vegetarian Menu Items is shown in Figure 6.9. In addition to the incorrect situation, Figure 6.9 includes a condition, the scope of the impossibility. If the ingredient is meat or fish, then it is impossible that that the menu item is vegetarian. But if the ingredient is neither meat nor fish, the rule does not apply.

You might have noticed the parallel between impossibility statements and prohibitive statements. Both say what cannot be. But impossibility statements are structural, explaining what cannot be by definition. Prohibitive statements are operative, explaining what should not be by policy.

When do you write your business rule as an impossibility statement? You use an impossibility statement when some situation is always false by definition. You write the false-by-definition situation as the incorrect situation. If a condition applies, you add it.

Restricted Possibility Statements

The last of the business rule forms is the restricted possibility statement. A restricted possibility statement is also a structural statement, describing something that is true by definition. Instead of describing what is always true (like a necessity statement) or what is always false (an impossibility statement), a restricted possibility statement describes what can be true only under certain conditions.

Let’s look at an example. Vegetarian Menu Items described earlier is an impossibility statement about vegetarian menu items. The same rule can instead be expressed as a restricted possibility statement, as Vegetarian Menu Items B.

Vegetarian Menu Items B: It is possible that a vegetarian menu item includes an ingredient only if the ingredient is not meat and the ingredient is not fish.

If an ingredient is neither a meat nor fish, it can be included in a vegetarian menu item. But if the ingredient is meat (or if it is fish), it cannot be included.

The structure of Vegetarian Menu Items B is shown in Figure 6.10. A restricted possibility statement starts with “It is possible that.” Next is a suitable situation, the situation that might be true. The suitable situation of Vegetarian Menu Items B is “a vegetarian menu item includes an ingredient.” After the suitable situation is “only if,” then the restriction that needs to be true for the suitable situation to be possible. In Vegetarian Menu Items B the restriction is “the ingredient is not meat and the ingredient is not fish.”

Restricted possibility statements are structurally similar to restricted permissive statements. Just as a restricted permissive statement describes a situation that is permitted, a restricted possibility statement describes a situation that is possible. Just as a restricted permissive statement has a restriction—a condition that must be true for the situation to be permitted—a restricted possibility statement has a restriction that must be true for the situation to be possible. The difference between the two is that a restricted permissive statement is an operative business rule, expressing what is permitted and the condition that needs to be true for it to be permitted. By contrast, a restricted possibility statement is a structural business rule. It expresses what is possible and the condition that needs to be true for it to be possible.

When do you write your business rule as a restricted possibility statement? You use a restricted possibility statement when a situation is allowed by definition but only under a restriction.

Business Rule Statements Summary

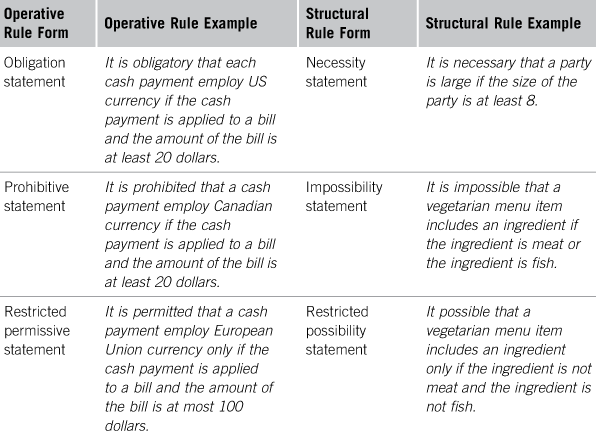

The six business rule forms are shown in Table 6.1. Note the parallel between the obligation statement and the necessity statement, between the prohibitive statement and the impossibility statement, and between the restricted permissive statement and the restricted possibility statement.

When you are writing a business rule, how do you decide which form to use? First you decide whether the rule you are writing describes a situation that must always be or whether it describes a situation that should be. In the former case, it is a structural rule; in the latter case, it is an operative rule. Then you decide which of the forms provides the simplest expression of the rule. Often the same rule can be expressed in multiple forms, but one form leads to a simpler expression. When writing business rules, simpler is better.

Noun Concepts

A business rule is expressed as an English sentence, but it is more formally stated than most sentences you encounter in everyday life. We have already examined one way business rules are more formally stated—the six business rule forms. Another way that business rules are more formally stated is how nouns are treated in a business rule. Just like any sentence in English, business rules contain nouns: words or word phrases that describe persons, places, things, animals, or abstract ideas. In business rules, the meaning of a noun is called a noun concept. There are many noun concepts at Mykonos. Just in our discussion in this chapter we have used more than 10: menu item, appetizer, ingredient, customer, order, bill, credit card, payment, personal check, cash payment, payment network. And there are hundreds of other noun concepts used in other rules at Mykonos restaurants and at Mykonos headquarters— noun concepts about ingredient freshness and spoilage, about unhappy customers, about waits and pagers.

Noun concepts are defined in a business rule model. Some noun concepts are defined with a definition from a dictionary, either a specialized technical dictionary for a technical term or an everyday dictionary for a common term. For example, the noun concept payment is defined as follows:

payment

Definition: an amount paid

— American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition

There are dictionary definitions for many of the other Mykonos noun concepts. But some terms are not defined in any dictionary. Consider cash payment. This is a useful term, an important building block for Mykonos business rules like “A cash payment must employ US currency” and in fact for business rules at any retail establishment that accepts cash. But cash payment is a bit too specialized for any everyday dictionary. Instead, we define it ourselves, using the definitions for payment and for cash.

cash payment

Definition: payment that employs cash

This definition means that cash payment is a specialization of payment and that any payment that employs cash is a cash payment. This definition is built on the noun concepts payment and cash. The latter is defined with a dictionary definition, as payment is.

cash

Definition: money in the form of bills or coins; currency

— American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition

Similarly, gratuity—used in the rules about allowable gratuities—is also defined with a dictionary definition.

gratuity

Definition: a gift of money, over and above payment due for a service, as to a waiter or a bellhop; tip

— Random House Unabridged Dictionary

Every noun concept used in a rule must be defined. There are two ways of defining a noun concept. Either you can use a dictionary or you can create your own definition, using other noun concepts you have already defined. Of course each of those previously defined noun concepts was itself defined, either via a dictionary or with other noun concepts. So ultimately everything depends on dictionary definitions.

Noun Concepts and Structural Rules

A noun concept can be detailed with a structural rule. As you will recall, a structural rule is a business rule that cannot be violated. It expresses a truth about the world or about the way the organization structures its knowledge about the world. It is true by definition.

Consider what happens when a party of 10 chooses to sit at two tables so they do not have to wait for one of the big tables to be available. When they sit at their tables, they become a separated party. The structural rule Parties 1 is true by definition. A separated party must be seated at two or more tables. Otherwise it is not a separated party.

Parties 1: It is necessary that a separated party is seated at two or more tables.

A structural rule is inherently definitional instead of prescriptive. Instead of expressing the behavior that Mykonos wants, it serves to detail a noun concept and the way the noun concept relates to other noun concepts.

Fact Types

Another way that business rules are more formally stated than most English sentences is their use of fact types. A fact type characterizes the way noun concepts may be related. For an example, consider again the prohibition on personal checks in No Checks.

No Checks: It is prohibited that a payment employ a personal check.

Implicit behind the rule is the idea that a personal check is the kind of thing that is conceivable to employ as a payment. Somewhere in the world there are restaurants that accept personal checks as payments—just not the Mykonos restaurants. By contrast consider the following statement that is not a rule at all:

Nonrule 2: It is prohibited that a payment employ autumn leaves.

Mykonos does not need to state Nonrule 2 because no fact type relates payments and autumn leaves. There is no restaurant in the world that accepts autumn leaves as a payment for burgers and fries. Autumn leaves are not a kind of thing that is possible to employ as a payment for a restaurant meal.

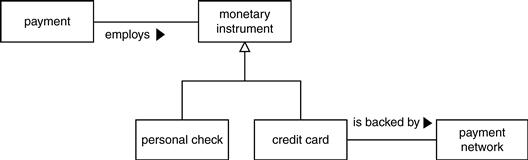

Behind No Checks is the fact-type diagram shown in Figure 6.11. A fact type diagram is a summary of what is expressible in rules. The sole fact type in Figure 6.11 can be read as payment employs personal check—that in principle a payment can employ a personal check.

Figure 6.11 is not a diagram of No Checks or in fact a diagram of any specific rule. Instead Figure 6.11 is a diagram of a single fact type that rules can build on. Figure 6.11 says that any rule that includes the noun concept payment and the noun concept personal check can relate those two noun concepts via the verb employs.

In addition to No Checks, the fact type of Figure 6.11 supports a huge variety of other potential rules. Some of these other potential rules are shown in Table 6.2.

Table 6.2

Other Potential Rules That Use the Same Fact Type

| Potential Rule | Interpretation |

| It is obligatory that a payment employ a personal check. | For that odd restaurant that requires all payments be made in personal checks. |

| It is permitted that a payment employ a personal check only if the personal check is drawn on a local back. | A personal check is acceptable if another condition holds: the check is local. |

| It is obligatory that a customer be photographed if the customer makes a payment and the payment employs a personal check. | For the careful restaurant that wants to collect forensic evidence from customers who might bounce checks. |

Note that the fact type diagram of Figure 6.11 complements the business rule form diagrams shown in Figures 6.2 through 6.10. Each of the business rule form diagrams shows the structure of one of the business rule forms. For example, Figure 6.3 shows the structure of an obligation statement—that an obligation statement begins with the phrase “It is obligatory that,” continues with a mandatory situation, then includes the word “if” and finishes with a condition. Figure 6.11 shows a fact type that can be used in the mandatory situation or in the condition, or in both.

Multiple Fact Types

A business rule can be built on more than one fact type. Actually, a rule like No Checks that is built on only a single fact type is an exception. Most business rules are built on multiple fact types. Consider VISA Only, the rule that restricts credit card acceptance to those that are backed by the VISA payment network.

VISA Only: It is permitted that a payment employ a credit card only if the credit card is backed by VISA.

VISA Only is built on two fact types: payment employs credit card and credit card is backed by payment network. Figure 6.12 shows the two fact types and the way they relate to each other. The noun concept payment is related to the noun concept credit card via the fact type payment employs credit card. The noun concept credit card is also related to the noun concept payment network via the fact type credit card is backed by payment network.

There is some overlap between Figures 6.11 and 6.12. Both include payment; both include employs, and both use it in the same way. Figures 6.11 and 6.12 can be combined into a single diagram shown in Figure 6.13. Figure 6.13 shows the fact types that both No Checks and VISA Only build on.

Figure 6.13 shows personal check as a specialization of monetary instrument. The specialization association is expressed in the diagram by the arrow with the hollow arrowhead, and it is expressed in English as “personal check” is a category of “monetary instrument.” The specialization means that a personal check is one kind of monetary instrument. Any associations that apply to monetary instruments also apply to personal checks. So we have a general fact type payment employs monetary instrument, and because of the specialization, we know that rules can be written about a payment using (or not using) personal checks. In the same way, credit card is a specialization of monetary instrument, and rules can be written about payments using credit cards.

Note that the association is backed by is between payment network and credit card. The employs association is at the more general level between payment and monetary instrument, applicable to all monetary instruments, but is backed by only applies to credit cards, not to other monetary instruments. With the fact types of Figure 6.13, we can write a rule about credit cards being backed by VISA, but we cannot write a rule about personal checks being backed by VISA.

Fact Type Consistency

Figure 6.13 combines Figures 6.11 and 6.12 into a single diagram. This combination is important. The rules that guide an organization should use a single coherent set of fact types. Consider what would happen if they did not—if each rule used whatever fact types made sense for that single rule, without reference to the fact types used by other rules. Instead of the previous payment rules, Mykonos might end up with these payment rules:

No Checks B: It is prohibited that a payment use a personal check.

Visa Only B: It is permitted that payment utilize a credit card only if the credit card is backed by VISA.

Greenbacks Only: It is obligatory that a cash payment employ US currency.

No Checks B is more or less the same as No Checks except that the underlying fact type is payment uses personal check instead of payment employs personal check. Similarly, Visa Only B is more or less the same as VISA Only except for the use of utilize instead of employ. In practice a server could figure out when an event violated one of these rules.

But what if Mykonos now wants to proscribe the use of multiple monetary instruments for small debts? Suppose Mykonos wants to prohibit the use of both credit cards and cash, unless the amount is large enough to warrant the trouble. A new One Monetary Instrument could be written to ban that activity.

One Monetary Instrument: It is prohibited that a payment employ more than one monetary instrument if the amount of the payment is less than $50.

But does One Monetary Instrument really do what we want? If a customer is both utilizing a credit card (per Visa Only B) and using a personal check (per No Ohecks B), is she really employing more than one monetary instrument? We are leaving much to the interpretation of individuals, and their interpretations will vary. It is better to have all rules build off a single coherent set of fact types.

Fact types that are more or less the same—but not quite identical—introduce problems into the business rules that build on them. These problems are a manifestation of a more general truth about business rules. Every business rule must conform to two different standards: It must be understandable to a business professional who reads it, and it must be written precisely, with each noun concept and each fact type defined consistently with the other business rules that use the same noun concepts and fact types. Only a business rule that is both understandable and precisely defined is useful for shaping behavior.

Properties

Consider the fact types that One Monetary Instrument builds on. We have already seen payment employs monetary instrument in other rules. But the other fact type is new: payment has payment amount. A payment has a payment amount, some quantity of money, perhaps more than $50, perhaps less.

The fact type payment has payment amount is treated a bit differently from other fact types we have seen. Payment amount is a property of a payment. A property means that one noun concept is dependent on the existence of the other. Without a payment, there is no payment amount. There is no such dependency between payment and monetary instrument. The VISA card in your wallet exists on its own, whether or not you use it today to make a payment. But if you don’t make a payment today, there is no payment amount. The existence of a payment amount is entirely dependent on the existence of a payment.

Figure 6.14 shows the fact types that One Monetary Instrument builds on. Note that the fact type payment has payment amount looks different from the fact type payment employs monetary instrument. The property payment amount is drawn without a rectangle surrounding it. It is drawn that way because it is a property—a property of payment. The association between payment and payment amount is labeled with “has,” and the fact type payment has payment amount also uses the word “has.” “Has” indicates that payment amount is a property of payment. “Has” is reserved just for properties. No non-property fact types use “has.”

Rule Violations

Earlier in this chapter we mentioned rule violation several times, relying on your intuition of what violation means. But now we need to be more precise. A business rule is said to be violated when an event or state of affairs occurs that should not, according to the rule. For example, when a customer pays a bill with Japanese yen instead of US dollars, the rule Greenbacks Only is violated. The server advises the customer that cash payments must be in US currency.

The customer might then attempt to pay for the bill with his JCB™ card—a credit card used widely in Japan and accepted by many US merchants but not by Mykonos restaurants. Thinking the card is a VISA, the server attempts to process the payment. Then the payments application notes another rule violation—a violation of the rule VISA Only. The application rejects the JCB card. Now the server takes the card back to the hapless customer and explains the second rule. One violation was spotted by a person, the other by an application. Either people or software can notice business rule violations.

Every operative business rule can be violated, at least in principle. Since the purpose of an operative rule is to describe what should be, a rule violation occurs whenever what should be does not actually happen—when people do not live up to the standards of the rule. For example, consider again the operative rule No Checks.

No Checks: It is prohibited that a payment employ a personal check.

Whenever a payment employs a personal check, No Checks is violated.

Only operative business rules can be violated. Structural rules cannot. Structural rules are true by definition, so a violation of a structural rule is impossible. To see why, consider again the structural rule Vegetarian Menu Items B.

Vegetarian Menu Items B: It is possible that a vegetarian menu item includes an ingredient only if the ingredient is not meat and the ingredient is not fish.

Suppose a vegetarian menu item included a meat ingredient. That seems like it might be a violation of Vegetarian Menu Items B, but it is not. If a menu item includes a meat ingredient, the menu item is not vegetarian at all, by definition. There is no violation because there is no vegetarian menu item.

Directly Enforceable

It must be possible for someone to decide whether a rule is being violated. If Joe knows a business rule and sees Emily do something, it should be possible for Joe to decide whether Emily’s action violates the rule or not. If a proposed rule does not admit this kind of decision, it is not a rule at all.

Let’s look at an example. At any Mykonos restaurant a customer can choose to give a tip to his server—a tip of any size. If the service if good, he might give 20 percent of the bill or even more. If the service is bad, he might give 5 percent or even nothing at all. It is all his choice. Unfortunately, in a large party, the server often gets stiffed; the customers collectively pay a small tip, much less than 10 percent. So, like many other restaurants, Mykonos specifies a minimum tip if the party is large. Nonrule 1 is an attempt to regulate that behavior through a business rule, but it does not succeed because Nonrule 1 is not a well-formed rule.

Nonrule 1: It is obligatory that the gratuity is at least 15% if the gratuity is applied to a bill and the bill is incurred by a party and the party is large.

The problem with Nonrule 1 is that it is not always possible to know whether the rule is being violated. Certainly a party of 24 is large, so if that party gives an 11 percent tip, Nonrule 1 is violated. And certainly a party of two is not large, so even if they give nothing, Nonrule 1 is not violated. But what if a party of six gives a 9 percent tip? Is a party of six large? What about a party of eight? A party of seven?

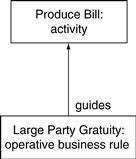

Nonrule 1 is said to be not directly enforceable. A rule is directly enforceable if someone who knows the rule and sees some behavior can decide whether the rule is violated. Nonrule 1 needs to be replaced by the directly enforceable rule Large Party Gratuity.

Large Party Gratuity: It is obligatory that the gratuity is at least 15% if the gratuity is applied to a bill and the bill is incurred by a party and the size of the party is greater than 7 people.

(Alternatively, the noun concept large party could be defined as a party whose size is greater than seven.)

Large Party Gratuity is directly enforceable. If Joe knows Large Party Gratuity and sees a party of six people apply a tip of 11 percent, he can determine that Large Party Gratuity is not violated. The party might be stingy, but they are not violating this rule.

Multiple Violations

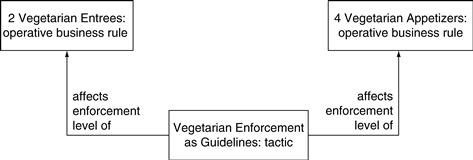

Most operative rules can be violated in more than one way. Consider the following rule about menus, meant to ensure that vegetarians always have at least two choices on every menu at a Mykonos restaurant.

2 Vegetarian Entrees: It is obligatory that each menu include at least two vegetarian entrees.

Obviously, 2 Vegetarian Entrees is violated when Angela Glaser—the head chef at Zona—creates a new menu with only a single vegetarian entree. But there is a second, not so obvious situation when 2 Vegetarian Entrees is violated. Suppose a menu has two vegetarian entrees: linguini puttanesca and grilled eggplant with goat cheese. Now Angela decides to add anchovies to enhance the linguini puttanesca. This addition may well improve the taste of the dish, but it also makes the entree no longer vegetarian. Her change to the entree violates the 2 Vegetarian Entrees rule.

A business rule shapes behavior when it is violated. Someone enforces the rule by noting the violation and explaining the rule to the violator. Or if the rule is enforced by an application, the application notes the violation and presents a dialog box to the violator. But a business rule also shapes behavior before it is violated, by the mere potential for violation. When our anchovy-happy Angela talks about her plan to a colleague, the colleague reminds Angela of 2 Vegetarian Entrees. Or Angela remembers the rule on her own and adds another vegetarian dish to the menu when she improves the linguini with anchovies. In either situation, the mere potential for violation triggers the business rule.

A single change can violate more than one rule. Consider the rule Visible Allergens, meant to protect people who have food allergies.

Visible Allergens: It is obligatory that the description of a menu item includes an ingredient if the ingredient is a common allergen.

Fish is a common allergen, one of the eight recognized by the US Food and Drug Administration. If Angela adds anchovies to the puttanesca sauce and does not change the menu, she is not only making things more difficult for vegetarians, she is also endangering anyone allergic to fish. Her one seemingly innocent change violates two business rules: 2 Vegetarian Entrees and Visible Allergens.

A violation of a business rule should be recognized as soon as possible. It does little good to recognize the violation of Visible Allergens after someone has an allergic reaction to a menu item that is inadequately described on the menu. It is better for the server to recognize the violation before the allergic customer orders the linguini. It is even better to recognize the violation before the menus are printed. And it is still better yet to recognize it when the change is being first contemplated, while the violation is still only a potential. With business rule violations, early recognition is better.

Enforcement

A rule does not specify what happens when it is violated. 2 Vegetarian Entrees is written solely about the behavior that is to be shaped by the rule. It is not written as Nonrule 3, with an explanation of the process by which it can be waived.

Nonrule 3: It is obligatory that each menu include at least two vegetarian entrees, unless an exception is authorized in advance by Mykonos Headquarters.

Instead of Nonrule 3, there is an enforcement level applied to 2 Vegetarian Entrees. The enforcement level indicates whether a rule is strictly enforced, whether it is merely guidance for the interpretation of people on the ground, or whether it is somewhere between. 2 Vegetarian Entrees is in fact somewhere between strict enforcement and guidance. 2 Vegetarian Entrees has an enforcement level of pre-authorized, meaning that the rule is enforced but exceptions can be authorized in advance.

2 Vegetarian Entrees: It is obligatory that each menu include at least two vegetarian entrees.

Enforcement level: pre-authorized

Why separate the enforcement level from the statement of the rule itself? In practice, the enforcement level of a rule will change more often than the rule itself. Mykonos might decide initially to enforce 2 Vegetarian Entrees strictly by setting the enforcement level to strict. After some experience is accumulated, the enforcement level is downgraded to pre-authorized.

Separating the rule from the enforcement level also supports different enforcement levels for different parts of the organization. There are more vegetarians in California than Texas, so Mykonos may decide to set enforcement to strict for the California restaurants and to merely override for the Mykonos restaurants in Texas. The rule is the same for all Mykonos restaurants, but the enforcement level is localized.

Every rule has a level of enforcement, one of the five valid enforcement levels shown in Table 6.3.

Table 6.3

| Enforcement Level | Meaning |

| Strict | The rule is strictly enforced. Anyone who violates the rule will be penalized. |

| Pre-authorized | An exception is allowed to the rule if the exception is authorized before the rule is violated. |

| Post-justified | An exception is allowed to the rule if the exception is approved after the violation. If the rule is violated and an exception is not later approved, the violator may be penalized. |

| Override | The rule may be violated as long as the violator provides an explanation. |

| Guideline | The rule is a suggestion but not enforced. |

The pre-authorized and post-justified enforcement levels require the existence of an authorizing organization—an organization that has the authority to grant exceptions to a rule. The strict enforcement level may also require an organization, one to administer the penalties. These are two ways that a business rule model and an organization model need to work together. Later in this chapter we will look at both these relationships between business rules and organizations as well as other relationships.

Business Policies

Earlier in the chapter, we examined 2 Vegetarian Entrees, the business rule mandating vegetarian entrees on menus.

2 Vegetarian Entrees: It is obligatory that each menu include at least two vegetarian entrees.

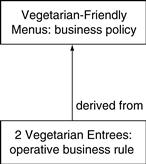

Why does 2 Vegetarian Entrees exist? Why is it important to include two vegetarian entrees on menus at Mykonos restaurants? The reason is a business policy. Mykonos has a business policy of making their restaurant menus vegetarian-friendly. They want to ensure that vegetarians feel welcome at Mykonos restaurants and that there are multiple options for them.

Vegetarian-Friendly Menus. All menus must be friendly to vegetarians.

Vegetarian-Friendly Menus is a business policy. Like a business rule, a business policy shapes behavior. But a business policy is less precise than a business rule and more subject to interpretation. 2 Vegetarian Entrees is a precise statement of what is allowed and what is not allowed. Vegetarian-Friendly Menus is more vague. It leaves open to interpretation whether a particular menu is friendly to vegetarians.

Earlier in the chapter we described how all operative business rules must be directly enforceable—that if someone knows the rule and sees a situation, she is able to tell whether the situation violates the rule. 2 Vegetarian Entrees is directly enforceable, but Vegetarian-Friendly Menus is not. If you know the rule and see a menu, how can you tell whether the menu violates the rule? In general, business policies are not directly enforceable.

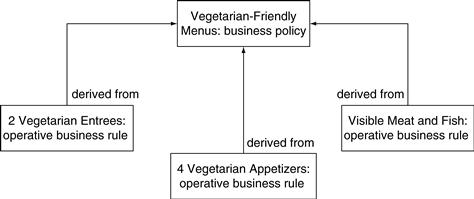

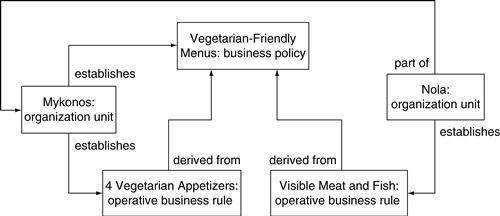

A business policy can be the reason that a business rule exists. For example, the business policy Vegetarian-Friendly Menu is the reason that the business rule 2 Vegetarian Entrees exists. 2 Vegetarian Entrees is an implementation of the business policy, a translation from the vague intention of the business policy into the precise, directly enforceable language of an operative rule. Figure 6.15 shows the business policy, the business rule, and the derived from association between them. The derived from association means that 2 Vegetarian Entrees is an implementation of Vegetarian-Friendly Menus.

More than one business rule can be derived from a single business policy. Consider the rules 4 Vegetarian Appetizers and Visible Meat And Fish. The first is much like 2 Vegetarian Entrees, except for appetizers instead of main courses. It ensures that there are at least four vegetarian options among the appetizers on any Mykonos menu. Visible Meat and Fish ensures that it is obvious from the description of a menu item whether it is vegetarian or not. Both serve to make Mykonos menus friendly to vegetarians.

4 Vegetarian Appetizers: It is obligatory that each menu include at least four vegetarian appetizers.

Visible Meat and Fish: It is obligatory that the description of a menu item include an ingredient if the ingredient is a meat or the ingredient is a fish.

Figure 6.16 shows the relationship of the three business rules and the business policy. All three rules are derived from Vegetarian-Friendly Menus.

Composing Business Policies

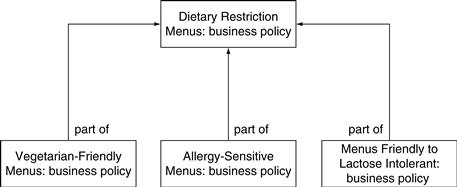

A business policy can be part of another business policy. Consider the business policy Dietary Restriction Menus.

Dietary Restriction Menus: All menus should cater to people with common dietary restrictions.

The business policy Vegetarian-Friendly Menus is a part of this larger policy of catering to people with common dietary restrictions. Figure 6.17 shows this part of relationship between Vegetarian-Friendly Menus and Dietary Restriction Menus. Also shown are two other business policies: Allergy-Sensitive Menus and Menus Friendly to Lactose Intolerant. Some people have food allergies and some people cannot digest milk or dairy products. Mykonos strives to make menus friendly to both these groups, in addition to vegetarians.

Mykonos has business rules that implement Allergy-Sensitive Menus and other business rules that implement Menus Friendly to Lactose Intolerant. Of course, there are many other dietary restrictions. Some people avoid beef for religious reasons; others avoid pork or shellfish. Some people shun all red meat; others avoid anything cooked in alcohol. Each of these dietary restrictions could have its own Mykonos policies and its own business rules to implement. The general policy Dietary Restriction Menus results in many business rules to guide the creation of menus.

Directives

Both business policies and business rules are directives. A directive is an element of guidance under the control of the business. Consider again the business rule 4 Vegetarian Appetizers. It is an element of guidance intended to shape the behavior of the Mykonos chefs (and others) designing menus. And it is under the control of the business. Mykonos has developed the business rule on its own, for its own reasons. Similarly, the business policy Vegetarian-Friendly Menus is a directive. It is an element of guidance intended not to shape the behavior of those creating menus but to be implemented in business rules that shape their behavior. And like 4 Vegetarian Appetizers it is under the control of Mykonos. No outside organization is commanding Mykonos to offer vegetarian-friendly menus; instead Mykonos personnel have decided on their own to offer them.

Business Motivation, Policies, and Rules

As you recall, in Chapter 3 we examined courses of action—ways that an organization achieves its goals and objectives. Courses of action come in two varieties: strategies—larger and more difficult to change—and tactics—smaller and easier to change.

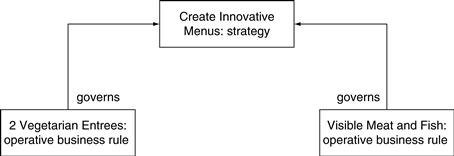

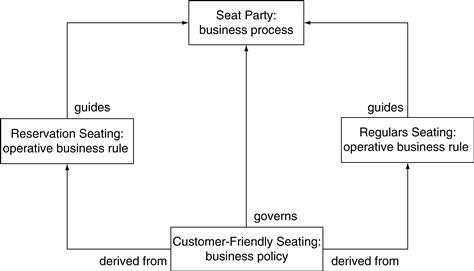

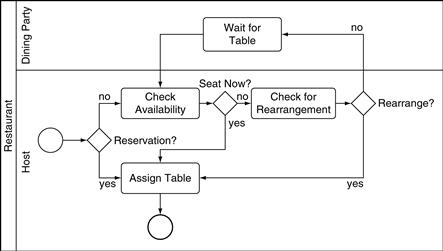

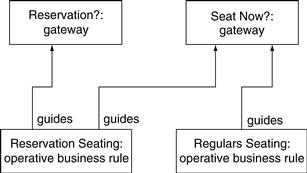

Business rules govern courses of actions. Consider the Mykonos strategy Create Innovative Menus. Mykonos management wants all Mykonos restaurants to create innovative menus. (Presumably this strategy channels efforts toward Mykonos goals, such as Expand Menu Variety.) But Create Innovative Menus is governed by the 2 Vegetarian Entrees rule. Mykonos wants innovative menus at its restaurants, but innovative menus that include at least two vegetarian entrees. Similarly, Create Innovative Menus is also governed by the business rule Visible Meat and Fish. Figure 6.18 shows the governs association between Create Innovative Menus and the two business rules.

What does it mean for a business rule to govern a strategy? The business rule shapes the way the strategy can be applied. The rule constrains the strategy; Mykonos intends to create innovative menus but will not do so in ways that result in menus with fewer than two vegetarian entrees.

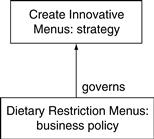

Business policies also govern courses of action. As you will recall, the business policy Dietary Restriction Menus requires that menus at Mykonos restaurants cater to people with common dietary restrictions. Figure 6.19 shows that business policy governing the strategy Create Innovative Menus. In practice this means that innovation in menus is constrained by many different business rules—all the business rules that are derived from Dietary Restriction Menus. The rules shown in Figure 6.18 are derived from this business policy, so Figure 6.19 is a simpler way of showing the associations of Figure 6.18. All directives—business policies and business rules—can govern courses of action, but it is often simpler to focus on the business policies.

Directives and Desired Results

In Chapter 3, we also introduced desired results—the goals that an organization seeks to achieve and the objectives that quantify those goals. Sometimes a directive supports the achievement of a goal. The most common situation of this kind of support is a structural rule defining a noun concept that is used in an objective. An objective is too vague to measure if the noun concepts it uses are not precisely defined. Structural rules can help define those noun concepts.

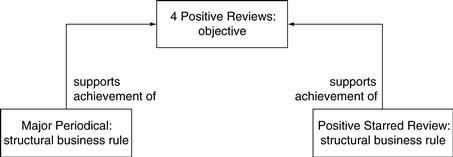

Let’s consider an example. The restaurant Nola has an objective 4 Positive Reviews, garnering four positive reviews in major periodicals in 2009. But what is a major periodical? Certainly The Washington Post is a major periodical. Is the much smaller weekly Washington City Paper a major periodical? And what exactly is a positive review? This objective needs support from some structural rules.

Major Periodical: It is necessary that a periodical is major if the periodical has a circulation and the circulation is at least 50,000.

Positive Starred Review: It is impossible that a review is positive if the review uses a five-star scale and the review has fewer than three stars.

Major Periodical supports the achievement of the objective 4 Positive Reviews by providing some precision about determining whether a periodical is major. Positive Starred Review also supports the achievement of 4 Positive Reviews—at least for reviews that are based on a star metric. Other metrics are supported by other structural rules. Figure 6.20 shows the associations between the objective and the two rules.

Directives and Assessments

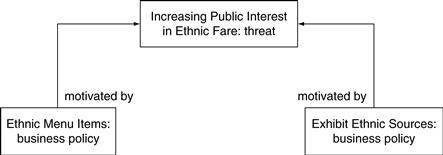

Also introduced in Chapter 3 were assessments: the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats faced by an organization. An assessment will often motivate the establishment of a directive. An organization recognizes a threat, and to counter that threat it creates a new business policy. For example, in Chapter 3, Cora Group recognized the threat Increasing Public Interest in Ethnic Fare. This was a threat to the Cora restaurants; as the interest in ethnic food increases, Cora Group restaurants could lose customers to competitors that feature Thai food, Ethiopian food, Bolivian food, and so on.

Since then Cora Group has been acquired by Mykonos, and Mykonos creates a new business policy, Ethnic Menu Items, to counter this threat. The new policy requires that menus feature some menu items inspired by ethnic cuisines.

Ethnic Menu Items: Menus must feature ethnic-inspired menu items.

Ethnic Menu Items is a reasonable policy, but it is not precise enough to be a business rule. From the policy it is not clear what it means for a menu item to be ethnic-inspired or how many menu items on a menu must be so inspired. Ethnic Menu Items is the basis for several business rules that define and implement this policy.

Figure 6.21 shows the motivated by association between the business policy Ethnic Menu Items and the threat Increasing Public Interest in Ethnic Fare. The motivated by association means that the directive is established because of the assessment—the assessment motivates the directive.

Figure 6.21 shows a second business policy motivated by Increasing Public Interest in Ethnic Fare. Mykonos leadership considers the ethnic fare threat to be as much image as reality. They say “all food is ethnic food”, certainly a bit of an exaggeration but no doubt one with some underlying truth. So they establish a second policy, one of illustrating the existing ethnic background of menu items in Mykonos menus. This business policy is Exhibit Ethnic Sources.

For example, Nola’s menu already includes orecchiette chicken mole, a dish with roots in both the Apulia region of southern Italy and the Oaxaca region of Mexico. With an explanation of the ethnic connections of the dish on the Nola menu, customers who are attracted to ethnic fare will be attracted to Nola.

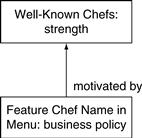

Directives can also be motivated by assessments that are not threats: by strategies, strengths, or weaknesses or even by other assessments that do not fit the SWOT framework. (If you recall from Chapter 3, SWOT analysis is a method of creating business strategy by identifying and analyzing the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of a business.) For example, many executive chefs who lead Mykonos restaurants have local name recognition, at least among those who know food. This name recognition is clearly a Mykonos strength. Mykonos can build on that strength with another business policy about menu design, a policy that the menu of a Mykonos restaurant should include the name of the executive chef of the restaurant. Figure 6.22 shows the trace association between the business policy Feature Chef Name in Menu and the strength Well-Known Chefs.

Tactics and Business Rules

Earlier in this chapter we explained that every operative business rule has an enforcement level. Some rules have an enforcement level of strict; those rules are strictly enforced. Other rules have enforcements levels of override or guideline or one of the other choices for an enforcement level.