Why Business Modeling?

A business model is a simple representation of the complex reality of a business. The primary purpose of a business model is to communicate something about the business to other people: employees, customers, partners, or suppliers. This chapter answers the two questions modelers face most often: what is a business model and why create one?

What is a model? A model is a simple representation of a complex reality that serves a particular purpose. We use many models in our day-to-day life: street maps, television schedules, 12-step programs, and furniture assembly instructions. We use models all the time without thinking about them.

Consider an example. You and a colleague fly to Washington, DC, to visit a restaurant. You aren’t there to eat; instead your employer is considering buying the restaurant—and the four others owned by the same company, Cora Group—and your job is to evaluate the place and offer a recommendation. The restaurant is called Portia, and it is downtown. Since neither you nor your colleague know Washington, you pick up a map as you rent your car. As your colleague drives, you interpret the map and guide her, telling her when to exit the highway and where to turn on the streets and thoroughfares.

Your map is a model. It is a simple representation of the complex reality of the city. It omits the smaller roads, the sidewalks and bike paths, the streams and electrical lines, the houses and shopping malls, the gas stations and office towers. It has just the few things you need to find your destination: the highways and major streets.

This model is built for a purpose: to find a destination while driving. If you were bicycling, you would use a different map, a model that showed the bike paths and bicycle-friendly streets. You would use a different map if you were taking mass transit, one that showed the train stations and bus routes. And if you were digging up the street to lay fiber optic cable, you would carry yet a different map, a model with the locations of the gas and power lines, existing communication cables, water and sewer pipes, and everything else you might find underground. For the same territory, different purposes require different models.

Perhaps your rental car includes a navigation system. Inside the navigation system is the same kind of model of the city’s road network, functionally similar to the printed street map. But instead of you reading the model and deciding where to go, the software interprets the model as your colleague drives, telling her when to turn right and how far you are from your destination. Models can be interpreted by people or they can be interpreted by software. Often a single model is built for interpretation by both people and software.

Just as a street map is a model of the far more complex reality of a city, a business model is a simple representation of the always far more complex business. A business process model is a business model, showing who does what work and in what sequence. A business organization model is a business model, showing how different people and organizations interact with each other.

The art of building these business models is called business modeling. This book is about that art, about how to create business models and how to solve problems using business models.

But first we must disambiguate. Sometimes when people talk about the business model of an enterprise, they are talking about something different from what we mean in this book. When they say “business model” they mean what the business sells. For example, “the business model of Google is selling advertising” means that Google makes its money by selling ads, not by selling automobiles or long distance telephony.

We mean something different. In this book the term “business model” is not just shorthand for what a company sells. Instead when we say “business model” we mean a model that describes the details of a business: its goals, organizations, business processes, or business rules.

The Rise of Business Modeling

Engineers use engineering models and have done so for many years. Every bridge, car, aircraft, and integrated circuit is created using models. Models are created to communicate with customers, to show how the product will look. Models are used to communicate with the engineer’s managers to illustrate issues that need management attention. Models are used to communicate between engineers with different responsibilities—for example, to plan how the electronics in an aircraft are to be powered. In engineering, models are ubiquitous.

Software engineering is a newer engineering discipline, and the use of modeling in software is more recent. Starting in the 1980s, some visionaries realized the value of software modeling. Many different modeling languages and methods were developed. Some of these languages and methods had followings, but none had mass usage. In the 1990s market demand increased, and Rational Software Corporation initiated the development of the Unified Modeling Language (UML), an attempt to unify the various modeling languages and methods. In 1997, Object Management Group adopted UML as a standard. UML is now widely used to design applications and systems. The use of UML is a mainstream practice for software engineers today.

Historically, business modeling has seen much more limited use. Of course, organizational charts and accounting models have been used since antiquity, but other than these two exceptions, business modeling has been rare until recent years. Until recently, businesspeople communicated using words, spreadsheets, and presentations, not business models.

Now this is changing. Businesspeople are increasingly using models to communicate. Over the last fifteen years, increasing numbers of people have built business models: models of the business processes of their organization, the goals and strategies, or the policies and rules.

We are seeing a progression from proprietary models and tools to new standards, the same kind of progression that occurred in software modeling in the 1990s. Business modeling is still a niche, but it is growing rapidly. In ten years, we expect business modeling to be mainstream, to be the natural and ordinary way for businesspeople to communicate, much as software modeling is mainstream today for software engineers.

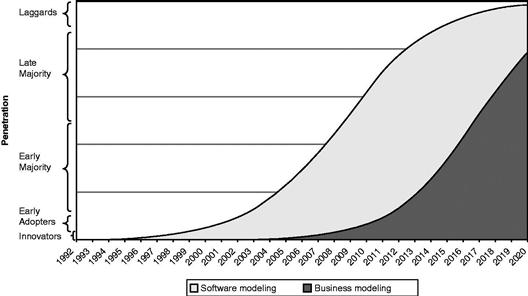

How does a technology such as business modeling become mainstream? What steps does it go through on its path to widespread use? Geoffrey Moore [Moore 1991] describes a technology adoption lifecycle, a depiction of how technologies progress from their inception to wide adoption and use. The technology adoption lifecycle describes who adopts a new technology as the technology develops. Initially a new technology is promising but rough around the edges. It is only adopted by innovators—people who experiment with new technologies, shape them, and improve them. As the technology improves, it is adopted by early adopters, who use a new technology to achieve a competitive advantage before the technology is solid or complete. Once a technology is mature enough, it is adopted by the early majority, a large group of people who welcome new technology once it is mature. After the early majority comes the late majority, who will only use a technology after it is widely adopted by others. Finally there are the laggards who are skeptical and only adopt a technology when they feel the large costs of being left behind.

The technology adoption lifecycle is a good framework for understanding the rise of business modeling, just as it was a good framework for the rise of software modeling in the 1990s. As shown in Figure 1.1, software modeling has penetrated much of the market now and is well into the early majority stage. The market penetration of business modeling is still early. Business modeling will go from a rapidly growing niche activity to a rapidly growing mainstream activity.

What’s driving the growth of business modeling? Why is it changing from a small niche activity into an increasingly mainstream technology? There are several drivers for the growth of business modeling. One driver is the changing economics of corporate information technology. As information technology (IT) budgets decline, IT organizations are using business models to align IT initiatives with business needs.

Business Modeling And It Alignment

In the late 1990s money flowed freely to corporate IT organizations. Companies raced to develop new applications, to integrate their existing applications and make them available on the Web, and to prepare their legacy applications against the risks of Y2K.1. Businesses competed in terms of how much they spent for IT, believing that every dollar spent would lead to competitive advantage and increased productivity. Wall Street analysts cheered them on, reporting the latest IT progress of the companies they covered.

Those days of exuberance have long passed. Since 2000, IT organizations have suffered declining budgets. Businesses now compete in terms of how little they spend for IT, preferring to direct their dollars other purposes: new business development, acquisitions, or stock dividends. Every IT expenditure must be carefully justified with the business benefit created by the expenditure.

Since 2001, we have helped corporate IT organizations use business modeling as a way to justify their IT expenditures. Using business models, they have connected the details of their desired IT spending with their business goals, business processes, and business rules. They have used business models to communicate the value of their IT plans. They have used business models to ensure alignment of those plans with their business needs.

Business Modeling and Business Transformation

Outside the cubicle farms of IT is the larger business that IT supports. During the last ten years, businessees have employed business modeling independent of the IT organization, for their own reasons. One reason is business transformation. Business transformations have become more common since 1995. Business models make those business transformations easier to manage.

Forty years ago, most businesses changed slowly. Martin Mayer [Mayer 1997] tells a story from the early 1970s of a retiring banker who was asked to name the most important business change he had seen in his career. His answer? Air conditioning. From today’s perspective, this story seems quaint, a picture of another, simpler (albeit sweatier) time.

Today, business transformations are common. Business transformations include changes of control: mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, and leveraged buyouts. Business transformations include changes of sourcing: outsourcing, offshoring, and many varieties of corporate teaming. Business transformations include changes in strategy and business process. And many businesses reorganize their reporting relationships and organizational responsibilities once or twice each year.

Business transformations are notoriously hard to manage. As a result, many transformations fail. For example, several banks merge, but many mistakes are made in the merger integration. Even years later the resulting bank is not a seamless whole but a motley collection of organizations glued together from the original legacy banks. As another example, a consumer product company offshores its customer support process to save money but suffers quality problems in the transition and alienates some customers. As a third example, an energy services company implements a software package, but the employees reject the new business process that the software package supports, trying to use their existing process with the new software. (This last example is explored in a case study at the end of this chapter.)

Business transformations are difficult because they always involve people. Technology challenges are easy compared to people challenges: ensuring that employees are ready for the change, that they understand what it means to them, and that they accept it. Most failed transformation projects fail for people reasons rather than for technology reasons.

Business modeling helps business transformations succeed. Why modeling? Models help with the implementation of change. If nothing changes, you don’t need models, just as you don’t need a street map if you never travel anywhere. If nothing changes, everyone in the organization already understands the organization’s goals and strategies because they have been elaborated endlessly by senior management year after year. Everyone already understands the business processes because they have worked within these processes for years. Everyone already knows the policies because everyone remembers when each policy was violated, who violated it, and the consequences of the violation.

But when things are changing, business models are useful. With a model, an employee can see the rest of the larger process in which he plays a small part, the rest of the process that he was only dimly aware of and that he now needs to understand well. With a model, he can understand the new business processes he will use. He can understand the new business rules he will follow. He can understand the new goals and strategies. Models help an organization move from today’s world to a future world, to implement a transformation. Business modeling has become more popular because business transformations have become more common.

Business Modeling and Managing Change

Business transformations are under your organization’s control. You decide to make a change in the organization structure or in a business process or in the partners you work with. You decide when to change and how. You are in control.

But change also happens due to external reasons, circumstances outside your control, in situations when you are not transforming yourself. For example, a key supplier is purchased by a competitor and you must react. A new technology threatens to displace one of your key products, and you must do something. Washington, DC, introduces tough smoking regulations, and Cora Group—the restaurant company we introduced at the beginning of the chapter—must adapt. Every day you must manage change, even when you do not intend to transform your business.

Ad hoc changes are rarely managed well. Things happen and people react as best as they can under the constraints of budget and time. Change is difficult.

Change would be easier if each change was finished before the next one started. But that kind of clean separation of changes never happens. Organizations are always dealing with many changes, all at once, in different stages of adaptation. Usually organizations struggle with these multiple simultaneous changes. For example, your company—Mykonos Dining Corporation—is considering the acquisition of the Cora Group. This acquisition is a big change for Portia and the other Cora restaurants. It will also change some things at Mykonos. There are new Cora Group employees to interact with and a different corporate culture. In addition, both Cora Group and Mykonos are already dealing with other changes within their own organizations. Cora Group is adapting to the recent ban on smoking in Washington. Mykonos is digesting other acquisitions and understanding how to react to changing customer demand.

Today change is mostly managed in isolation. A single change is applied independently to every organization within the business. Each organization handles the change within its own structure and applies the change to its own processes. Little coordination is performed across the business or with business partners.

Business models are useful for managing change. Some business models help us understand the motivation and reason for the change. A business model can explain to Cora Group why Mykonos is interested in the acquisition. To a Cora Group employee, the Mykonos motivation matters. Is Cora Group being acquired to increase revenue? To expand into a new market? As a defensive move to respond to a competitive pressure by another company? To open one of the Cora Group’s unique restaurants in another city? A model helps make the acquisition successful by ensuring everyone has the same understanding, and by dispelling myths and misinformation.

Business models also help us see the changes that result from the change. What will the new reporting structure be? Will Cora Group be completely consumed or will it maintain its own reporting under Mykonos? Where will new restaurants be opened and who will be responsible for them?

With a business model, we can see how the goals will be met. For example, today Cora Group outsources its human resources function to a third-party restaurant HR company. With a business model, we can see how a centralized Mykonos human resources function will operate and support the restaurant staff.

Business models also show what is affected by a change: what processes change and which roles change. Employees in both Cora Group and Mykonos can compare how they perform work today against how they will perform that work in the future, to better understand how their everyday lives will change.

Models are maintainable, making them a natural tool for managing change. Static artifacts such as PowerPoint™ presentations and Word™ documents have a short shelf life; they become out-of-date quickly. Modifying a static document with each change takes time and effort. Models are easier to keep up-to-date within a modeling tool because a single model change updates many diagrams at once. Models also support change because they support analysis techniques that show the consequence of a change. Chapter 10 describes model analysis.

Business Modeling and Managing Complexity

Business transformation and managing change are two important drivers of the increasing interest in business modeling in recent years. But there’s another important driver: the need to manage increasing complexity. Businesses have become more complex. Twenty years ago, businesses were easier to understand. There were fewer business processes, fewer products and services, less data stored in databases, fewer business partners, and fewer lines of business. Now things are more complex. There are more of everything: more business processes, more products and services, more data, more partners, and more lines of business. Businesses require multiple specialists—subject matter experts in different domains—to understand all aspects of their work.

Complexity is the key problem in business today. Decisions are harder now because there is more to consider. A company might not understand how its business partner accomplishes its work internally. This lack of understanding can cause poor decisions for the supply chain as a whole.

For example, when a medication is prescribed to a patient, four trading partners are involved. A pharmaceutical manufacturer (e.g., Merck, Pfizer) actually makes the medications. A health care provider (e.g., the Cleveland Clinic) purchases medications on behalf of its patients. A distributor (e.g., Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen) purchases the medications and sells them to the providers. A group purchasing organization (e.g., Novation, Premier) negotiates prices on behalf of the providers for the medications it purchases. So when a physician at the Cleveland Clinic prescribes Singulair—a Merck medication for treating asthma—to a patient, the Cleveland Clinic has purchased Singulair through a distributor. The purchase is based on a contract between the Cleveland Clinic and Merck negotiated by a group purchasing organization, a GPO. GPOs represent hospitals and other healthcare organizations, pooling their purchases for improved pricing. The price negotiated applies to that medication only on the specific contract. Other providers will pay different negotiated prices for Singular.

The distributor has purchased Singulair from Merck based on a single standard acquisition price. The providers are all eligible for different prices based on the contracts they have. The distributor must understand the different prices each provider will back for each medication, to apply the right discounts. For example, when the distributor provides Singulair to the Cleveland Clinic, the hospital will claim it is eligible for its discounted price. The distributor then applies to Merck for a “chargeback” fee, the difference between its acquisition price and the hospital’s discount.

So what happens when Merck changes prices for its medications? To Merck, this might seem like a simple internal decision, a new price for one of its products. But to the distributor, this simple price change can be difficult to implement. The distributor must figure out how the price change affects the contract (negotiated by the GPO) between the Cleveland Clinic and Merck. If the distributor makes a mistake and provides the medication to Cleveland Clinic at the wrong price, the distributor might later lose money because their chargeback is rejected.

The price change is made more complex by the numbers the distributor faces. The Cleveland Clinic is only one hospital of the many on the same contract and only one contract out of thousands that the distributor tracks.

And the problem is not just with pricing. The Cleveland Clinic may become ineligible on a contract, perhaps because it changed its group purchasing organization affiliation. Instead of one GPO, it negotiates a deal with another. The distributor now charges the wrong price to the Cleveland Clinic until it becomes aware of the new affiliation.

Merck also adds new medications and discontinues existing medications. When the four trading partners have any differences in their understanding of medication, pricing, and eligibility, they have problems doing the right thing. A change by one trading partner impacts everyone else, in unforeseen ways.

The pharmaceutical supply chain is certainly complex, but we see similarly complex situations in other industries.

Why does complexity matter? In this pharmaceutical situation, there is a large cost incurred by all four trading partners to synchronize information and to repair information divergence. Each trading partner employs specialized departments whose sole job is to synchronize and repair. Across the United States, roughly $1 billion is spent each year in the pharmaceutical supply chain on information synchronization and repair.

Complexity is a driver of the rise of business modeling. With business modeling, each party can understand the impact of its decisions on its trading partners. With business modeling, each party can make less risky decisions. Today, no one understands the whole picture, and without understanding no one can make good decisions for the benefit of the whole. Instead people make decisions based on their own limited local understanding, without understanding the impact on others.

Dynamic Complexity and Detail Complexity

Peter Senge refers to the complexity that results from making local decisions as dynamic complexity. “When an action has one set of consequences locally and a very different set of consequences in another part of the system, there is dynamic complexity. When obvious interventions produce nonobvious consequences, there is dynamic complexity.” [Senge 1990] Senge contrasts dynamic complexity with detail complexity. Senge’s colleague John Sterman describes detail complexity as “the number of components in a system or the number of combinations one must consider in making a decision. … [The] complexity lies in finding the best solution out of an astronomical number of possibilities.” [Sterman 2000]

Business models help manage detail complexity. Business models are simpler than the world they model. Only some of the detail complexity of the world is present in a model, a limited view of what is most important.

Even though they are simpler than the world they model, business models can still have a lot of detail, too much for anyone to understand all at once. Good business models are carefully designed to show only some of that detail in any one diagram, allowing you to explore the detail you want to consider now and ignore the rest, the detail that is not important for your current task.

A good business model supports different views of the same underlying knowledge. Each subject matter expert can see what they need to see, for their own purposes. Each can ignore the detail needed for other subject matter experts. For example, a strategist can look at an organization’s goals, strategies, and tactics, ignoring the business processes and interactions. A sales specialist can examine the business processes supporting sales, ignoring the processes supporting operations and maintenance.

Business models also support dynamic complexity. They show the relationships between organizations, showing who interacts with whom and how they interact. The interactions expose the dependencies and show the impact of a change. Business models show the cause and effect relationships between organization’s strategies and the influencers in the organization’s environment, influencers such as competitor behaviors, customer purchases, and supplier innovations.

The Business Value of Business Models

Many people question the business value of business models. They ask why is it worth spending the time to create a model. This is a valid business question. As you build models, you will find that you often have to justify your modeling efforts with the economic value you expect to create.

Indeed, business modeling does take time, effort, and special skills. In our experience, business models create value, often significant value. They can more than earn their keep.

In our experience, business models generate value in eight ways. Business models support:

• Communication between people

• Analysis of a business situation

• Development of software requirements

These eight ways of generating business value are not mutually exclusive. A single business model can be used for both communication and analysis, or for both compliance checking and for later knowledge management. Once built, a model provides many kinds of business value. We explore how to manage the value of a business model in Chapter 2, and we will return to these eight ways of generating value many times in the following chapters.

Communication

Business is a communication-intensive activity. Businesspeople give presentations about company performance. Businesspeople talk to their clients and their suppliers about new products and services. Business colleagues talk to each other about the changing competitive environment. Much of business is communication.

Some of that communication is complex. For example, business policies change. When a new policy is introduced, businesspeople discuss the dozens of business rules that need to be changed to implement the new policy.

Today most people use words, on-the-spot drawings, and PowerPoint presentations to communicate on these complex topics. These ad hoc solutions work, more or less, but they have some problems. Misunderstandings happen. People interpret the same words differently. People also interpret the same PowerPoint slides differently. Today, complex business communications leak knowledge. The words and ad hoc drawings fail to convey the rich content that is intended.

Business models are better for conveying complex business information. Business models don’t replace the words or the presentations. Instead they compliment the communication by providing something rigorous and concrete to point to. The words and the slides are enhanced by the models.

Different people in a business need different detail. For example, when you return to your company—Mykonos Corp.—to report on your evaluation of Cora Group for acquisition, you will make several presentations. To Mykonos marketing, you will describe how well the Cora Group restaurants fit the Mykonos portfolio, whether they are similar enough to the restaurants you already own to fit the Mykonos brand and strategy. Marketing needs to understand the customers, locations, and competitors. To Mykonos operations, you will describe your assessment of how well the Cora restaurants are run. They need to understand the organization, processes, and policies. To the executive team, you will describe how the business is performing. They want to understand finances and strategy.

Business models support the presentation of different details to different audiences. To operations, you show a detailed model of the Cora business processes of procuring fresh fish. To marketing, a high-level model of the same process is sufficient, so they are aware of the commitment to fish freshness.

Business models are effective for communication because most models are visual. We humans are visual beings; we have sophisticated visual processing engines built into our brains. Most business models are shown as visual diagrams to take advantage of this visual processing. Diagrams make a model easier to understand and faster to communicate.

Business models facilitate a common understanding of a business situation. When two businesspeople create an on-the-spot drawing of a business process, they might think they agree on the process, but they can actually disagree because each interprets the drawing differently. Does Joe’s diagram box mean the same thing as Sharon’s? With a model, the modeling elements are rigorously defined. The same model means the same thing to anyone who sees it. (Or at least the modeling elements are intended to be rigorously defined, with the same meaning for everyone. In practice, the rigor is a matter of degree. But relying on business models certainly leads to much less accidental misunderstanding than relying on informal drawings.)

Why is rigor important? Communication is all about finding common ground. In some languages (e.g., Hebrew) the same word is used for hello and goodbye. The meaning is determined from the context. If you begin a telephone conversation with someone and you do not agree on the form of communication, when you say hello the other person might hang up. Modeling is similar. The model and its semantics—the meaning of each model element—is an agreement that allows for information to be conveyed in a consistent manner. As long as those who create the model and those who read it have the same understanding, the model can be interpreted to have the same meaning.

People with different backgrounds can use models to communicate, as long as they agree on the meaning of the modeling elements. Someone purchasing a home might not be skilled in reading the builder’s plumbing or electrical diagrams. However, a floorplan can be used as a common model among the purchaser, the plumber, and the electrician. The floorplan is a baseline framework for common understanding. The floorplan includes modeling elements that are familiar to all: stairways, walls, closets, and doors.

Business models are used for communicating project scope. The scope of a project is its extent or range, what is included in the project, and, by implication, what is not included. Every project has a scope. Every corporate reorganization has a scope, as does every business process outsourcing, every application implementation, and every asset sale. When working on a project, businesspeople must communicate about the scope. Business models are useful for that communication. For example, a business process model can be used to communicate which processes are to be outsourced and which are not. As another example, an organization model can be used to communicate about who will use a new software application.

Business models are useful for communicating changes. For example, in your evaluation of the Cora Group for acquisition, you discover that the company outsources its human resource function to a specialized company that handles employee benefits, wages processing, hiring agreements, and the like. Your company, Mykonos, has a centralized HR function to provide HR in a consistent way across all restaurants. Instead of duplicating the HR functions, one centralized group handles everything. When you have acquired restaurants in the past, you have displaced internal HR personnel. For Cora Group, there is no one to displace; Cora Group has no internal HR today, so no existing HR employees are affected by the acquisition. But the HR processes will change for all Cora Group employees. There are processes for scheduling shifts, for hiring, and for payroll and benefits. If in fact you acquire Cora, you can use business models to explain the change to the Cora Group employees. You show simple, easy-to-understand models of how they will interact with HR and what they need to do.

Training and Learning

People learn in two ways. They learn from their own experience, via trial and error, and they learn from other people’s experiences, via conversations, books, or classroom material. Learning from other people’s experiences is of course cheaper, faster, and less risky. We allow others to make mistakes instead of making our own.

Business models are one way of learning from other people’s experience. First, a model is built of the expert’s knowledge of the business rules or the business process. Then many novices can study the model to learn what the expert knows.

Business models are surprisingly useful in training. Business models are rigorously defined, so all novices learning the model are more likely to learn the same thing. There are fewer differences in interpretation among the novices learning the modeled material.

There is another reason business models are useful in training situations. Business models communicate a different kind of knowledge, how-to knowledge that is hard to communicate in other ways. A business process model naturally communicates the task-by-task detail of how a job is performed.

Persuasion and Selling

In business, persuasion is ubiquitous. When we sell a customer on a product, we are persuading. When we pitch a new initiative to our management, we are persuading. When we convince employees to embrace a business process change, we are persuading. Persuasion is communication, of course, but it is communication in service of a goal: convincing someone to take action favorable to us, to our organization, or to themselves.

Business models are useful for persuasion. When you use a business model in a pitch, you look like an expert. You might actually be an expert in the topic and so deserve that recognition. Or perhaps the model was created by a colleague, and the model helps you convey your company’s expertise. In either case, the business model bestows credibility on you and credibility to the people you are trying to persuade.

The people you are persuading have problems. Business models demonstrate your depth of understanding of their problems. Suppose you are proposing to the Cora Group that it increase its sales by offering outdoor seating in the warmer months at Cora Group restaurants, expanding its capacity during the seven months that it is pleasant to be outside in DC. You create a business model of the sales challenges the company currently faces, how the limited capacity affects its revenue goals. The model shows Cora Group you understand its issues.

Business models also demonstrate your understanding of solutions. To Cora Group, you show a model that compares three scenarios: adding outdoor seating, changing the menu, and hosting live music. Your model demonstrates the rigor of your approach. You are showing more than words. You are showing you have been thorough in your analysis and selection of the solution. The model helps you back up your claims.

Analysis

Insight is power. The business with better insight into a customer problem is more competitive. The business with better insight into how to use resources efficiently makes more money. The business with better insight into the customer touchpoints has more satisfied customers. The business with better insight into the impact of a new regulatory policy can adapt faster.

Analyzing business models provides insight. For example, if you acquire Cora Group, you will inherit Cora Group’s existing supplier relationships, relationships with the companies that provide the company with fish, wine, spices, kitchen equipment, and the other sundries that a restaurant needs. Many of those Cora Group suppliers compete with existing Mykonos suppliers. As part of the acquisition, you need to decide which Cora Group suppliers to keep and which to discontinue. Analyzing a business model of the interactions with Cora Group suppliers and Mykonos suppliers can help you figure out what suppliers you want.

Analyzing a business model is particularly useful when you have a decision to make. The different alternative scenarios can be modeled and the models then analyzed and compared. For example, you may compare different business process scenarios to see which is the lowest cost. That low-cost scenario can be compared to today’s business process so that you can understand what activities need to change, what new activities need to be performed, what activities should be automated, and what skills you will need to learn.

Compliance Management

Businesses must comply with law, government regulations, and other guidance. They must comply with terms of contractual agreements with their lenders, suppliers, and customers. Corporate employees must comply with corporate policies. Compliance often impacts financial results. Sometimes the impact is larger than money; noncompliance can lead to jail.

Businesses need to manage their compliance. They need to check it, to ensure that they are adhering to regulations and policies. If the business is not compliant, it needs to understand how far from compliance it is. It needs to design processes to ensure compliance. And when regulations change, it needs to understand the impact of the new regulations on its business.

Business models help with compliance management. An organization can model a new business process that complies with a new law. The existing process can be compared to determine the differences and what must be done to achieve compliance. A project plan can then be created to close the compliance gap.

The new process can also be used in compliance training. By including the new process in the training, all employees will understand the desired state in the same way. Employees can learn what they must do to ensure company compliance.

Requirements for Software Development

Requirements provide a description of what a proposed software application should do. In developing software, requirements are critical. Without requirements, software developers get lost in the details of code. Without detailed requirements, application development projects fail.

Historically, a requirements document was a dry line-by-line listing of the various things an application must do. For example, “the application shall support 50 concurrent users” is a typical line in a requirements document. Requirements documents explained what functionality the application needed, but rarely did they capture the real needs from the end user’s perspective.

End users hate requirements documents because they have a difficult time relating to the details the documents describe. End users do relate well to descriptions of the essence of what they do. What activities do they perform to accomplish their work? What goals does their work meet? What metrics can be created to measure their performance and how well they are doing in achieving the goals? Who do they interact with in performing their work?

Business models capture this detail in a way that is understandable to both the business users and the software developers. Business users do not need to understand how the system will be created; they need to understand how it will support their need. Business models are a better form of requirements for end users.

Direct Execution in Software Engines

At the beginning of this chapter, we described using a map to navigate through Washington, DC, and compared that to the maps embedded in automobile navigation systems. A map can be used by people to make decision or by software to make decisions. Business models can also work like that. A business model can be used by people to make decisions, as in the examples we have explored so far. Or a business model can be used by software to make decisions.

Later in the book, we will examine an expense reimbursement process, a process in which employees are reimbursed for expenses they incur on behalf of their employer. This process can be directly executed (by an appropriate software engine) so when an employee claims an expense, the expense is automatically routed to the right individuals for approval and ultimately for payment. The advantage of direct execution is that the process can be changed—for example, to route expenses for greater than $1000 to a senior vice president for an additional approval. The change is then automatically executed by the engine. No software needs to be changed; only business models.

Knowledge Management and Reuse

Knowledge management is the practice of systematically capturing knowledge from some people in an organization so that the knowledge can be used by others elsewhere in the organization. Knowledge management aims to turn the everyday documents people create and use into a source of economic value for other people.

Today, the typical knowledge management approach is to collect documents, index them, store them, and make them accessible to others. Later, people can search for keywords and find relevant documents, discovering what others have done before them. Once captured, a document is no longer something personally available only to a few; instead it is now an organizational asset, available to many. People coming later do not have to reinvent the hard-won knowledge. They can learn what was done and repurpose it.

But knowledge management practices today capture only half the relevant knowledge. Typical knowledge management practices capture the explicit knowledge found in existing documents but not the tacit knowledge found in people’s heads. Tacit knowledge includes what people do and how they do it. Tacit knowledge includes when each document is used and why.

For example, Crystal is a server at Adelina, one of the Cora Group restaurants. Crystal is quite good at upselling wines. She can recognize the right situation to suggest a more expensive wine, and she is successful at convincing her customers to try something new. She understands the different wines on the Adelina winelist and which wine is appropriate for which meal, which occasions, and which tastes. Crystal’s knowledge of wine upselling is not found in any Adelina document. It is tacit knowledge, not explicit knowledge.

Business modeling converts tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge. The details of business rules, the activities in a business process, and the goals and tactics are all captured and made explicit when they are turned into business models. In Crystal’s case, the knowledge of wine upselling was captured in a collection of business rules that could be taught to others. These rules could be adapted for the winelists of the other Cora Group restaurants and so lead to higher wine sales across the board.

When business modeling is practiced, knowledge management becomes more useful. The tacit knowledge can now be managed along with the explicit knowledge. The other half of the knowledge can be captured.

The Rigor of Business Modeling

As we discussed earlier, engineers have long used models in designing all manner of engineered objects. The engineering models bring rigor to the design process. We can feel safe driving over a bridge, because we know engineers created a model of that bridge and carefully analyzed cars driving over it.

Business modeling aims to bring the same rigor to business. Business models address the motivation of the business, the business processes, the organization, and the policies.

Rigor is critical. Would you invest in a business that had sloppy business processes? Would you acquire a business that was not organized to achieve its mission? Would you work for a business whose policies doom it to failure? Models provide the rigor needed to improve your business. Businesses that use modeling are better businesses.

Case Study

Enterprise resource planning systems—usually called ERP systems—are packaged applications that attempt to support all the basic functions of a business. ERP vendors implement features that they believe to be common to many organizations. When a company purchases an ERP, it can either adapt its business to the software or customize the software to its business. In the 1970s and 1980s, most large companies developed their own systems to support their needs. Nowadays, most large companies use ERP systems to support human resources, accounting, inventory, and other basic functions.

A few years ago a large energy company decided to replace its legacy systems with a new implementation of an ERP package. The company evaluated several ERP packages from different vendors and selected one that had domain-specific modules to support the energy market. The company then embarked on an implementation of the ERP package it purchased and budgeted several million dollars for that implementation, a typical expenditure for implementing ERP.

The company performed no business modeling. Its managers didn’t understand how their business processes fit with the business processes supported by their ERP system. They didn’t understand how their policies differed from the policies supported by the ERP system. They didn’t even realize that there were big differences.

As they began their implementation, end users discovered some of the differences. The differences resulted in customization requests to make the software fit the business. Then more differences were discovered, and more customization was performed. The original costs and schedule budgeted for the ERP implementation did not include customizations. Overruns happened.

Without a common way to understand the problem, there was miscommunication among IT staff, the ERP vendor, and corporate management. Corporate management thought that with an additional $2 million the customizations would be finished and the result would be an operational system that matched the company’s business processes. The ERP vendor understood that with over 1000 customizations, the application had become too different from its baseline. The vendor could no longer support the application. Corporate IT realized that the 1000 customizations would have to be ported to the next version of the ERP platform, and the next one after that. Each port would be a completely new deployment. Each would cost between $6 million and $8 million.

When the parties finally understood the situation, heads rolled and the parties were forced to resolve their differences. Everyone suffered.

The company could have avoided this mess by using business models. If the company’s managers had developed business models of their business and what the ERP package supported, they could have realized the magnitude of the gap. Knowing the gap, they might have selected a different package, one that fit their business better. Or perhaps none of the ERP packages were close enough to their business, and they could have developed a new custom application to support their business, using the business models to drive their requirements.

If they did select an ERP package, they could have adapted their business to the package rather than customizing the software. Business models would have helped them identify exactly what they needed to change in their business and helped them manage the change as it unfolded. Business models would have helped train the employees in the new processes and policies. Business models would also have helped in communication through the ERP deployment, providing a consistent picture to corporate management, the ERP vendor, IT, and the employees. Business models would have saved this company millions of dollars and saved the jobs of the senior managers.

A business model is a model that describes the details of a business: its goals, organizations, business processes, or business rules.

Business models are created because they produce business value. They make it easier for people to communicate, learn, and persuade. They support analysis of complex situations, and they support compliance with laws and policies. They serve as requirements for software development and can be executed directly in special-purpose software engines. And they capture knowledge for others to use later.

Chapter 2 explains the four different business modeling disciplines and what each discipline attempts to model.

1Y2K was the effort to correct software problems with date calculations beyond December 31, 1999.