Business Model Analysis

Much can be learned about a business by analyzing its business models. There are several different techniques for business model analysis—techniques appropriate for different business situations. This chapter explains how to analyze a business model.

The Mykonos attorneys are worried. Last month a prestigious Los Angeles restaurant was sued by a customer who claimed he became sick after eating undercooked beef. The restaurant settled the suit for $3.4 million, despite some doubt whether the customer became sick because of their food or even whether the customer was sick at all. Mykonos was not involved in this lawsuit, but the Mykonos attorneys are worried nonetheless. If restaurant disease lawsuits become popular, Mykonos would seem to be an attractive target: a large cash-rich company with many restaurants cooking a great variety of food that might sound strange to jurors who are only familiar with the more mainstream fare served at Chili’s™ and Applebee’s™.

The Mykonos attorneys want to reduce the risk of being sued. Mykonos food is already safe; all the restaurants comply with all the local health regulations. But the attorneys want to reduce the legal risk, so they create a small task force to change policies and business processes, a disease lawsuit task force.

Fortunately for the task force, the Mykonos business processes and business rules are already modeled, as these business models—created originally for other purposes—are useful for determining what to do about the risk of lawsuits. The task force examines the business processes, looking for ways to reduce legal risk. They consider the menu creation process and introduce a new activity into the process to review new menu items for legal risk. They examine the new server hiring process and decide to add some new training for servers, so the servers can explain food preparation to customers. And because Mykonos acquires so many existing restaurants, they change the process by which restaurants are acquired, to make sure that they are not acquiring future lawsuits.

The disease lawsuit task force analyzes the existing business models to determine how they can reduce the risk of lawsuits. Their effort is an example of business model analysis, mentioned in Chapter 1 as one of the eight ways that a business model can create value. Business model analysis is the work of analyzing existing business models to learn more about the business. Business model analysis is about reaping value from models, using the models to discover new insights. The disease lawsuit task force uses the business process models to discover new insights into how to reduce liability risk—how to make some minor changes to the processes to have a big impact on the risk of a lawsuit.

In Chapter 7 we described several ways to improve a business model to make a model simpler and easier to understand. We analyzed business models in that chapter, but it was analysis with a different, inward focus. In Chapter 7 we were concerned with deciding whether to create a model, and we used model value analysis to make that decision. We were also concerned with improving a model once it is created. All this analysis is about improving the modeling, analyzing a model for the benefit of the model. By contrast, our focus in this chapter is outward. The business model analysis described in this chapter is analysis with the purpose of improving the business being modeled, or at least the purpose of better understanding that business.

Analysis Techniques

There are several different analysis techniques, several different ways to wring insight from an existing business model. Each analysis technique has its own methods. Each technique is used for a different business purpose. In this chapter we explain four techniques, as shown in Table 10.1. Improvement analysis is using a model to find ways to improve the business. Transformation analysis is using an as-is and a to-be model to understand how a business must be transformed from the as-is to the to-be. Impact analysis is using a model to understand the impacts of a proposed change to the business. Acquisition analysis is using a model to determine whether to acquire another business.

Table 10.1

| Analysis Technique | Business Purpose | When Applicable |

| Improvement analysis | Improve the business | Always, because businesses can always be improved |

| Transformation analysis | Support a proposed transformation to make it easier and more likely to succeed | When there is an existing plan to transform the business |

| Impact analysis | Discover the consequences of a proposed change | Before a proposed change is made to the business |

| Acquisition analysis | Determine whether to acquire another business | When a merger or acquisition is considered |

Business change is the common thread among the four model analysis techniques. All four techniques are about business change in some way. Improvement analysis is finding useful changes to make to the business. Transformation analysis is about supporting a big change to the business—a sweeping transformation. Impact analysis is about discovering the consequences of a proposed business change. Finally, acquisition analysis is determining whether and how to undertake the dramatic change of merging with another business. Model analysis is always about business change.

Simulation could be considered a model analysis technique. Simulation is certainly a method of extracting insight from an existing model. So Table 10.1 could have included a row for simulation analysis, and we could have described simulation in this chapter on model analysis. But we did not, for two reasons. Business simulation is complex enough—and different enough from the other analyses—to warrant its own chapter, Chapter 11, the longest chapter in our book. And unlike the other model analysis techniques in Table 10.1, simulation is used for a wide range of business purposes. In fact, simulation can be used for each of the four model analysis techniques. Simulation can be used to discover ways to improve a business, to support a transformation, to understand an impact, or to analyze an acquisition. Simulation is one way to realize the model analysis techniques.

Table 10.1 is not intended to be exhaustive. There are other model analysis techniques not listed in Table 10.1 and not described in this chapter. In fact, model analysis is a creative process. When you analyze a model, sometimes none of the existing techniques fit your needs, and you must create a new technique. There is much room for innovation in analyzing business models.

Improvement Analysis

Every business can be improved. No business is perfect; there are always opportunities to make business processes faster, to improve the accuracy of decisions, or to change the organization structure in ways that improve customer satisfaction. Even when a business is well designed for a particular environment, it never stays that way. The business environment continually changes. A business that fit the environment yesterday will fail to fit today. Business improvement is a never-ending task.

A business model can be analyzed for improvement opportunities—opportunities to improve the business that is modeled. The analysis of a business model to discover improvement opportunities is called improvement analysis (naturally). The goal of improvement analysis is to find ways to improve the business, to use the model to better the business. Improvement analysis is not about improving the model. Improvement analysis is different from the techniques explained in Chapter 7 for making more accurate and more useful models, although sometimes opportunities for improving models are found along the way, as a side effect of performing improvement analysis.

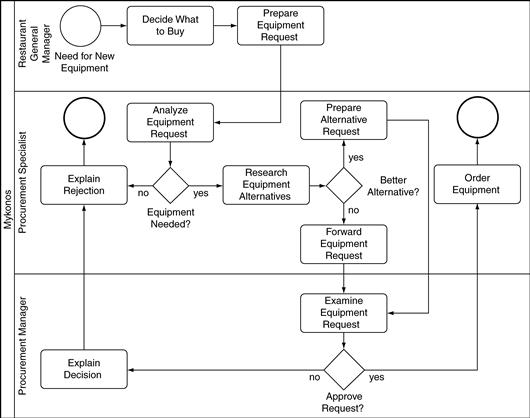

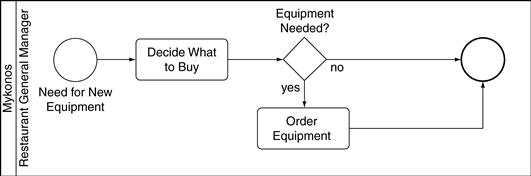

Let’s consider an example. Each Mykonos restaurant is responsible for acquiring its own cooking equipment—the ranges and ovens and broilers that it uses to prepare food. Sometimes equipment is replaced, and sometimes new equipment is purchased to augment the existing equipment. A purchasing process is followed to procure the new equipment, a process shown in Figure 10.1. The process starts when a restaurant general manager recognizes that a purchase is required. The general manger decides what to buy and prepares an equipment request. A procurement specialist from Mykonos headquarters analyzes the request and decides whether the equipment is needed. If it is in fact needed, he researches whether an alternative purchase might make more sense, whether an alternative might be cheaper or better. He forwards his recommendations to the purchasing manager, who makes the final determination of whether new equipment is needed. If the purchasing manager approves the purchase, the procurement specialist orders the equipment. The general manager learns about the order after it is placed or after it is rejected.

Mykonos is interested in changing the procurement process. It takes too long and costs too much. There are too many handoffs, too many times that the process is handed off from one person to another. The successful acquisition of new equipment requires four separate handoffs: a handoff from the restaurant general manager to the procurement specialist to analyze the request, a handoff from the procurement specialist to the procurement manager to approve the request, a handoff back from the procurement manager to the procurement specialist to actually order the equipment, and finally a handoff back to the restaurant general manager—or at least a conversation with him to notify him that the order was placed. In one process path, four handoffs are required just to reject the request.

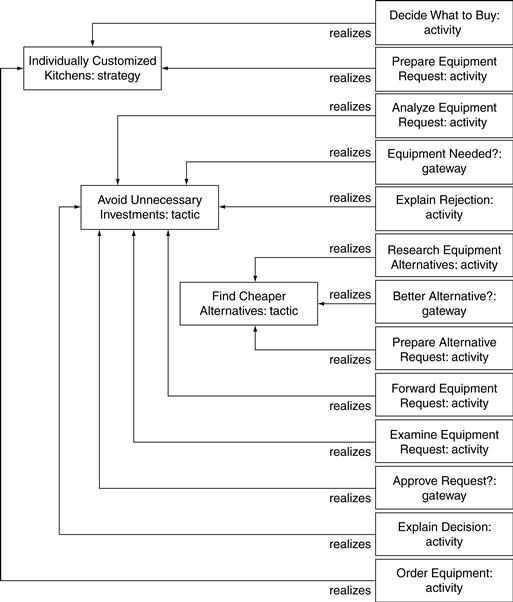

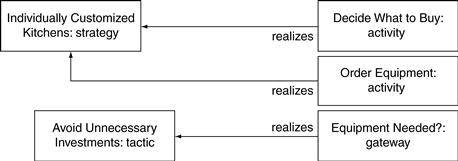

Can some of the handoffs be eliminated? Why are all the activities in Figure 10.1 performed? Are they all truly necessary? These questions can be answered by analyzing the motivation behind each activity. Figure 10.2 relates activities in Figure 10.1 to elements in the Mykonos business motivation model.

In Figure 10.1 the restaurant general manager decides what new equipment to buy in the activity Decide What to Buy. This activity realizes the Mykonos strategy of creating kitchens that are customized to the needs of the individual restaurants. Each Mykonos restaurant is different, with a different menu. So each Mykonos restaurants has a unique kitchen, one individually customized for the needs of that restaurant, reflected in the strategy Individually Customized Kitchens. The activity Decide What to Buy realizes that strategy. The same strategy is also realized by the activity Prepare Equipment Request and much later in the process when the equipment is actually ordered from the vendor in the activity Order Equipment.

Mykonos has some financial objectives and tactics to achieve those objectives. One such tactic is avoiding unnecessary investments, modeled in Figure 10.2 as Avoid Unnecessary Investments. Many of the activities and gateways in Figure 10.1 are performed solely to realize this tactic. For example, the procurement specialist performs the activity Analyze Equipment Request to determine whether the investment can be avoided. Similarly, the procurement manager plays a role avoiding unnecessary investments with the activities Examine Equipment Request and Explain Decision and the gateway Approve Request? Altogether seven activities and gateways in the equipment procurement process realize the tactic of avoiding unnecessary investment.

A third course of action is also realized in the Figure 10.1 process. Mykonos has established the tactic Find Cheaper Alternatives. The procurement specialist attempts to find those cheaper alternatives in the activities Research Equipment Alternatives and Prepare Alternative Request and in the gateway Better Alternative? In Figure 10.2 those three model elements all realize Find Cheaper Alternatives.

Business Process Simplification

We have examined the business process model for the procurement process and the motivations behind each of the business process model elements. Now it is time to consider how to improve the business process, using what we know. In particular, now it is time to consider how to simplify the business process. Business process simplification is changing a business process, typically removing activities but also sometimes replacing activities with others. Business process simplification is performed for a business reason, either to reduce the cost of the business process, improve the quality, reduce the end-to-end cycle time, or for some other reason.

Much of Chapter 7 was concerned with model simplification—techniques to keep models simple to read and understand. Model simplification is an important objective but different from our focus now: business process simplification. When we perform business process simplification, we are not just changing our model of a business process, creating a simpler model to reflect the same business process. Instead we are changing the business process itself, eliminating activities that are currently performed. Chapter 7’s focus was about creating a better model. Our focus now is creating a better business.

Often a business process will have some activities and gateways that are not justified by any courses of action. The process includes activities that are performed for no apparent reason, no reason beyond tradition: we have always done it this way. These unnecessary activities might once have had a rationale. Long ago they served a purpose, but the strategies and tactics of the organization changed. Now they are only vestigial organs, remnants of a half-forgotten past. And now they can be removed. Any activity or gateway that realizes no course of action today can be eliminated.

We see no vestigial activities or gateways in the procurement process. Every gateway in Figure 10.1 realizes some course of action, as shown in Figure 10.2. So does every activity. Everything in the Mykonos procurement process has a purpose.

But all three courses of action incur a cost. There are five activities and two gateways in the procurement process to achieve the tactic of avoiding unnecessary investments. Of the 13 model elements in the end-to-end process, more than half are there solely for that purpose. There must be an easier way, and there is. Instead of relying on the procurement specialist and the procurement manager, Mykonos could make the restaurant general manager responsible for avoiding unnecessary investments. The general manager could be measured by his success in managing investments, just as he is managed by his success in revenue, critic reviews, and other metrics.

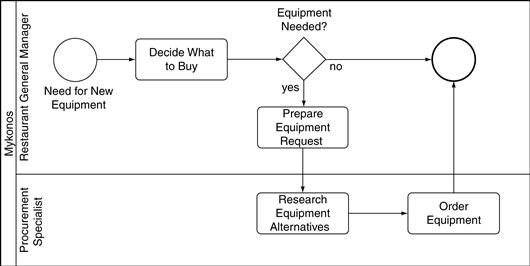

Figure 10.3 shows the resulting simplified business process. The restaurant general manager decides himself whether the equipment is needed. Once he decides to purchase, the procurement specialist determines whether there are cheaper alternatives and then purchases the equipment. The whole approval and rejection process is gone.

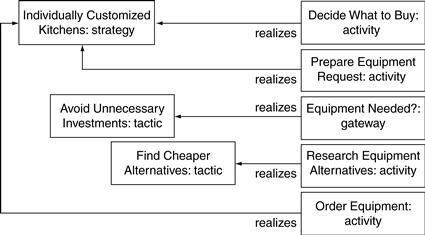

Figure 10.4 shows how the activities and gateways in Figure 10.3 are motivated by Mykonos courses of action. Figure 10.4 has the same strategy and the same tactics as Figure 10.2. The strategy Individually Customized Kitchens is realized by the same three activities in Figures 10.2 and 10.4. But Avoid Unnecessary Investments is different. Instead of being realized by six activities and two gateways in Figure 10.2, it is realized by a single gateway in Figure 10.4: Equipment Needed?

Course of Action Valuation

As we saw in Figures 10.1 through 10.4, the careful comparison of a process model with a motivation model can lead to a consideration of changes in the business process. It can also lead to a consideration of changes in strategy. With the model, we know what courses of action are realized by which activities and gateways. We can measure the cost of a course of action by summing the costs of all the activities and gateways that realize that cost. Then the total cost of efforts toward the course of action can be weighed against the benefits. This improvement approach is called course of action valuation.

Let’s look again at the procurement of equipment. After examining the models in Figures 10.1 and 10.2, Mykonos personnel consider whether the tactic Find Cheaper Alternative is useful. Yes, Mykonos saves $100, sometimes $200, by comparison shopping for kitchen equipment when a purchase is made. But much time is spent on the extra activities. Even in the simplified process of Figure 10.3, the activity Research Equipment Alternatives takes 3.2 hours of work. The process is also slower. A simulation reveals that the process in Figure 10.3 takes an extra 2.7 business days to complete a purchase after the procurement specialist receives the work. The people performing the procurement specialist tasks are also doing many other more pressing activities in other processes.

Does the value of pursuing this course of action really justify the cost and time to pursue it? Mykonos might be better served by letting the restaurant general manager make the purchase, holding him responsible for the financial results, and performing an occasional audit to guard against corruption. The resulting business process is shown in Figure 10.5 and the connection to motivation elements in Figure 10.6.

Both the process shown in Figure 10.3 and the one shown in Figure 10.5 are significant simplifications over the original process of Figure 10.1. But there are some costs of making the change: the costs of training the general managers on the new process and changing the application that supports today’s process. And there are risks as well. The general managers might not make good business decisions about their kitchen equipment. They might be swayed by the allure of owning the best restaurant kitchen and fail to properly consider the costs to Mykonos. Are the benefits worth the cost? Mykonos—like any organization considering a business process simplification—must weigh the risks. The business models inform that weighing.

Other Improvement Approaches

Business process simplification is used often; it is an important approach for improvement analysis. Course of action valuation is not used as often. In practice companies are frequently reluctant to examine the costs of their strategies. But course of action valuation is powerful. It exposes expensive strategies—strategies that sound good in theory but in practice are not worth the effort of the business process activities that implement them.

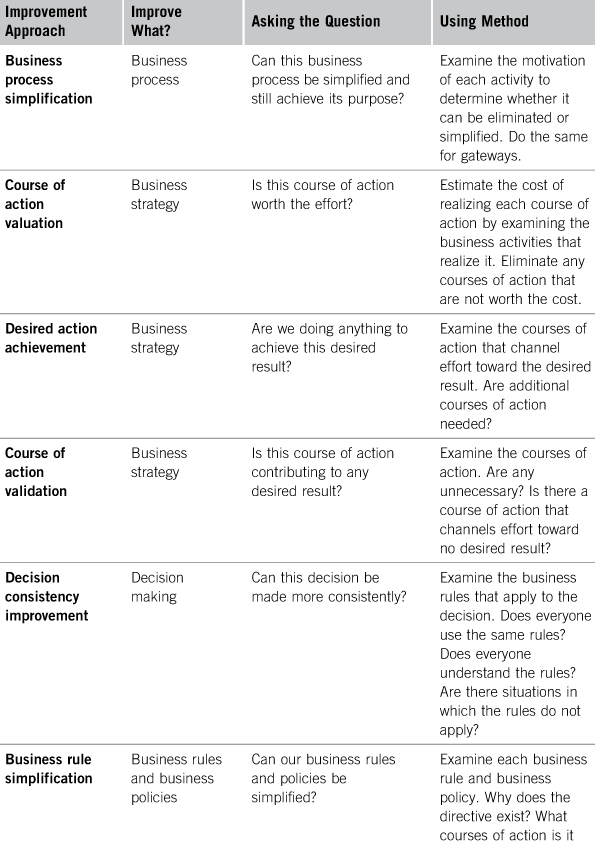

There are also other improvement approaches, other ways of analyzing a business model to discover how to improve a business. Table 10.2 lists eight improvement approaches: both the two already explained and six others. Each approach includes what is meant to be improved, whether the approach is meant to improve the business process, the organization structure, or something else. Each approach attempts to answer a question. For example, business process simplification attempts to answer the question, “Can this business process be simplified and still achieve its purpose?” And each approach includes a summary of the method—how to actually apply the approach.

Transformation Analysis

Often businesses make small, measured changes, adding a new activity to an existing process or revising one policy out of hundreds. But sometimes a business will conduct a significant business transformation, making a far larger change all at once. The business completely reengineers a business process from beginning to end. Or it conducts a vast reorganization, moving all employees from one organization structure to another. Or a large business has been acquired and after the acquisition it must be integrated into the business that acquired it.

Executing a business transformation is always difficult. The problem is sheer scale. It is simply much harder to make large changes to a business than to make small changes. Many transformation efforts fail, and even those that succeed often achieve only some of the original goals.

Transformation analysis is the use of business models to support business transformation. The purpose of transformation analysis is very different from the focus of improvement analysis. Whereas the purpose of improvement analysis is discovering opportunities to improve a business, the purpose of transformation analysis is supporting a transformation effort, supporting an existing plan for dramatic improvement in the business. If improvement analysis is like using models to determine what to improve in a building, then transformation analysis is like using models to perform the actual improvement.

In Chapter 5, we described how several several to-be business processes can be compared to decide which to-be business process should be adopted. Transformation analysis is different. Transformation analysis is not about comparing multiple to-be models and making decisions among them. Instead transformation analysis is about driving to a single to-be that has already been determined. Transformation analysis is not about deciding, it is about executing a decision that has already been made.

Let’s consider an example. After completing the improvement analysis of the equipment procurement process (as described earlier in this chapter), Mykonos decides to implement the changes. The as-is equipment procurement process is shown in Figure 10.1. The to-be process is radically simpler, as shown in Figure 10.5. Now your challenge is executing the change, transforming from the as-is process to the to-be.

You start by comparing the as-is process and the to-be, looking for activities that have changed. What activities are performed in both the as-is and the to-be but are performed differently in the to-be? One such changed activity is Order Equipment, the final activity in the process and the activity in which the new equipment is actually ordered. The purpose and mechanics of the activity are the same in the to-be as in the as-is, but a different person is performing the activity. In the as-is process, the procurement specialist orders the equipment. In the to-be process, the restaurant general manager orders it. This change in resource performing the activity is significant. The general managers must be trained on how to order equipment, including training on the procurement application that Mykonos uses to support the ordering. The application itself must be changed a bit so that general managers can track their equipment orders. And of course access to the application must be provided for them.

Ideally all these training and software costs would have been considered originally when deciding whether or not to change the process. But when transformation analysis occurs, it is too late for second thoughts. The decision has been made to change the process, and the goal is to execute that process change.

The gateway Equipment Needed? changes in a similar way. In the as-is process the procurement specialist decides whether equipment is needed. In the to-be process, the restaurant general manager makes this decision. To effect the change, each general manager must be trained in how to make the decision—how to determine whether the new equipment makes sense economically.

Although the gateway Equipment Needed? appears in both the as-is process and the to-be, it encapsulates a somewhat different decision in the to-be. To see why, let’s examine the as-is gateways more carefully. There are three decisions in the as-is process. First, the procurement specialist decides whether the equipment is needed, in the gateway Equipment Needed? Second, the procurement specialist decides whether there is a better alternative to the requested equipment, in the gateway Better Alternative? And finally, the procurement manager decides whether to approve the request, in the gateway Approve Request? In the to-be process, there is only a single decision, made in Equipment Needed? The second as-is decision is simply eliminated. In the to-be process there is no longer a separate activity to comparison shop. The general manager is responsible for selecting the best equipment. Similarly, the third as-is decision is eliminated and the responsibility rolled into the to-be Equipment Needed? gateway. The restaurant general manager does not just decide whether he thinks new equipment is needed. He also commits Mykonos to the purchase.

The to-be Equipment Needed? decision replaces both the as-is Equipment Needed? and the to-be Approve Request? The restaurant general manager will need to be trained in how to consider the financial interests of Mykonos when deciding whether equipment is needed.

Eliminating Activities and Adding Activities

After analyzing the activity and gateway that have changed, you look for activities that are eliminated, ones that exist in the as-is but not the to-be. In transforming equipment procurement, there are many such eliminated activities. In fact, most of the process is eliminated, including the following activities and gateways:

Most of these eliminated activities and gateways are performed by procurement specialists. So now we must ask about redundancy. Do we need as many procurement specialists in the new organization? Is this work a significant part of what they do today or a minor distraction from their main role? If it is a significant part of what they do, we need to either reassign the people to new work or to perform a layoff.

The to-be equipment procurement process has no new activities; both activities in Figure 10.5 were already in Figure 10.1. But often when a business process is transformed, new activities are introduced. With new activities come new training, new software support for these activities, and perhaps even hiring new people.

Redesigning the Mykonos equipment procurement process is something of a small transformation. It is a radical rethinking, giving financial responsibility over kitchen equipment investments to the restaurant general managers. But the radicalism is very contained; it only involves a single process, and a rather simple one. Many transformations are larger, involving multiple processes and including strategies, organizations, and business rules. Transformations are often big.

Impact Analysis

When a single change is made to a business, many consequences can occur. A new governmental regulation, seemingly simple, can lead to three new policies, a new organization to monitor compliance, and 13 changes to business processes. A small business process improvement can lead to one organization being underutilized and another far too busy.

Before making a change, wise executives try to understand the impacts of the change. What will happen if we make this change? What unintended consequences will result? The attempt to understand the impacts of a proposed change before acting on the change is called impact analysis. Impact analysis is looking before leaping.

What is the value of impact analysis? Sometimes the value is avoiding making a bad change, a change that has unforeseen impacts. At other times the change itself is unavoidable. The business must comply with a new regulation. Impact analysis allows the business to understand the consequences before they happen, and prepare for those consequences.

Without models, performing impact analysis is difficult. Businesses are complex, with many organizations, rules, and processes that interrelate in hundreds of ways. Without models, even the most thoughtful and thorough executives will miss some impacts. Furthermore, sometimes executives are mistaken in their understanding of how the business works. Models help avoid the consequences of those mistakes.

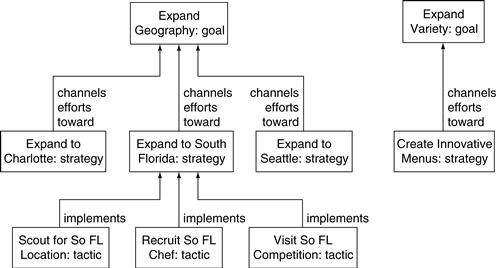

Let’s reconsider the disease lawsuit task force, described at the beginning of this chapter. As you recall, the task force was chartered to reduce the risk of a lawsuit based on real or imagined ailments resulting from consumption of food at Mykonos restaurants. The task force begins its work by considering the existing Mykonos motivation model. Are there courses of action or desired results that will lead to increased risk of a lawsuit? Figure 10.7 shows part of the motivation model, with two goals and the strategies that channel efforts toward those goals. The goal Expand Geography does not increase the risk of a lawsuit. Two of the strategies that channel efforts toward the goal—Expand to Charlotte and Expand to Seattle—are also safe. But the third strategy is a problem: Expand to South Florida. The South Florida courts are known to be sympathetic to tort innovation, and multimillion-dollar awards are common. The task force decides to abandon the strategy of expansion into South Florida.

When Expand to South Florida is abandoned, other motivation elements are affected. Figure 10.7 shows how the tactic Scout for So FL location implements the strategy Expand to South Florida. This tactic is abandoned with the strategy Expand to South Florida. It makes no sense to scout for locations when no restaurant will be opened there. Similarly, the tactics Recruit So FL Chef and Visit So FL Competition also implement the same strategy and are eliminated with it.

Figure 10.7 also shows the goal Expand Variety, with the supporting strategy Create Innovative Menus. With the new legal environment, creating innovative menus carries a risk. An innovative menu with unusual combinations of ingredients is more likely to attract a lawsuit than a menu of steaks and grilled fish. But the task force does not want to abandon the strategy Create Innovative Menus as they abandoned the strategy of expanding to South Florida. Innovative menus are just too important. In this situation the cure is worse than the disease. Instead the task force adopts a new business policy to govern this strategy.

Legally Safe Menus: All menus must be reasonably safe from lawsuits.

The new policy Legally Safe Menus is intended to reduce the risk of a lawsuit by creating legally safe menus—menus that are (probably) not going to lead to lawsuits. This policy is the basis for several business rules that check aspects of legal safety. For example, a new business rule is created to ensure that all meat is sufficiently cooked.

Meats Sufficiently Cooked: It is obligatory that each menu item is thoroughly cooked if the menu item contains meat.

As the restaurant lawsuit threat evolves in California and elsewhere, new business rules are created and existing ones are revised to enforce this general policy of keeping menus safe from lawsuits.

How to Perform Impact Analysis

There is no magic in performing impact analysis. In our example the Mykonos disease lawsuit task force simply examines each of the business models to check which are impacted by the new legal risk. That is how impact analysis is performed. The change is considered, and then model elements are examined one by one to see which are affected by the change.

When a model element is affected by a change, the impact can have one of several different results. A new business policy or business rule may be required, as in the previous example in which the new policy Legally Safe Menus is created to reduce the risk of lawsuits. A business process activity might be eliminated or modified in other ways. For example, if pagers are to be installed, the host still greets and seats customers but now does so differently because a pager system is used.

Impact analysis takes time. If your business has many models and model diagrams, you must check them all for impact. This checking is not hard work. It is usually easy to determine whether a change under consideration affects a goal or a business process activity. But the work takes some time because every model element must be considered.

Acquisition Analysis

Sometimes one company buys another company and the two are combined to form a single, larger company. This purchase is called either a merger or an acquisition, depending on the legal details of the transaction. For our purposes in this book, the legal distinctions between a merger and an acquisition are not important, and we will use the terms interchangeably. In either case, a decision is made to combine two companies into one.

Prior to an acquisition, the acquirer performs a financial analysis, trying to understand how the acquired company will perform under new ownership. Will sales increase when a vastly larger sales force sells the acquired products? How much? Can costs be cut as redundant operations are combined? How much? This financial analysis is necessary for determining an appropriate financial value for the company to be acquired.

The success or failure of an acquisition often rests not on these financial issues but on the ease or difficulty of post-merger integration, the combining of the two companies into one after the acquisition occurs.1 Can the acquired company be easily integrated into the acquirer? What actions must be taken to perform the integration? How long will the post-merger integration take? This assessment of the size and effort of post-merger integration can be performed using business models. By comparing business models of the two companies, we can identify differences that will lead to integration work.

Let’s look at an example. After the acquisition and integration of Cora Group, Mykonos is ready to consider purchasing another restaurant company. You have been asked to evaluate the purchase of Pescado, a restaurant company based in Houston that consists of 11 restaurants. Pescado serves the same market as Mykonos—business professionals and consumers who are willing to pay $100 for an unusually good dinner for two. But the Pescado restaurants are a bit different. Except for a few vegetarian entrees, the menu is entirely fish and seafood. And everything is alive until a few minutes before it is prepared. When a diner orders sautéed sea bass, the server leads him to the sea bass tank and the diner selects his fish from the 15 sea bass swimming around. His sea bass is then caught, scaled, and prepared.

The tanks are part of the attraction of the Pescado restaurants. Dining there is like eating at an aquarium, with dozens of tanks around the walls. Some of the fish are there only for display, not intended for consumption. Others are on display until they are selected, replaced by fresh live fish the next day or the next week. All restaurants have an element of the entertainment industry, but Pescado is closer to show business than most.

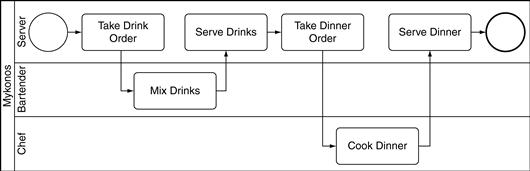

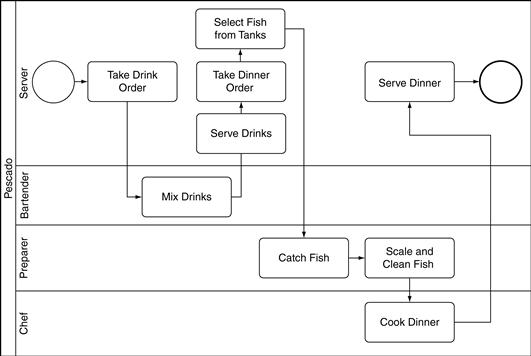

As you perform your analysis of Pescado, you look at the business processes. You begin with the basic Mykonos customer dining process shown in Figure 10.8.2 The equivalent Pescado process is shown in Figure 10.9. There are three additional activities in the Pescado process that are not performed at Mykonos. The activity Select Fish from Tanks is unique to Pescado, as is Catch Fish and Scale and Clean Fish. There is an entirely new role with its own new swimlane: Preparer, the role that performs the catching and the scaling and cleaning. You wonder about the costs of this new role and the additional time these new activities will add to the preparation of the dinners. Is the entertainment worth the cost and time?

The procurement process for fresh fish is also different. At Mykonos restaurants, the general manager estimates the evening’s fish need, and then the chef buys the fish. The very simple process is shown in Figure 10.10.

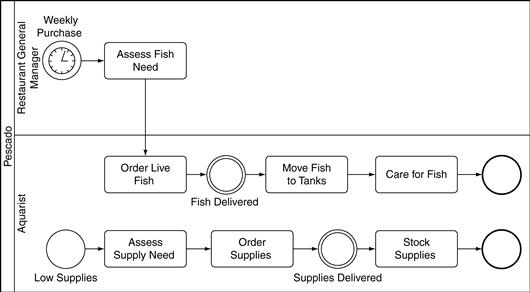

The same process at Pescado is much more complex. Figure 10.11 shows the process. The fish are purchased alive, and they must be kept alive until they are consumed. A new role is responsible for ordering the fish and caring for them once they are delivered; this person is an Aquarist. Figure 10.11 includes a second process as well, also perform by the aquarist. He orders the supplies the fish need, particularly the specialized foods for each fish species, and the aquarium parts and equipment.

After some comparison of the procurement processes, you conclude that the Pescado process and the Mykonos process will never be integrated. The Pescado fish procurement process is just too fundamentally different from the Mykonos fish procurement process: different activities, different timing, even different roles. And the Pescado customer dining process is also very different from the Mykonos one. The processes must be different, and each must be maintained. Given the costs of maintaining separate processes, you start to wonder whether there is really any value in acquiring Pescado.

How to Perform Acquisition Analysis

To perform acquisition analysis, you simply compare models from the acquiring company and the target company. You find differences between the models and consider the impact of those differences. How hard will it be to integrate the business processes? How hard to merge the organizations, given their existing interactions? As with impact analysis, there is no magic.

There are some common obstacles to acquisition analysis. First, it is likely that the target company will not be already modeled. If you are performing the analysis on behalf of the acquiring company, you will have models for your company but not for the target company, the one your company is about to buy. You must model it, creating models for the business processes or organizations you want to compare.

If the target company is already modeled, the models are likely to be of low quality. Today most business models are poorly constructed, with many of the flaws described in Chapter 7. If models already exist, you might need to spend some time improving them: making them consistent, bringing them up to date, and making them easier to understand.

Of the four business modeling disciplines, all are useful for acquisition analysis, for somewhat different reasons. Comparing business process models is quite useful. Often companies perform the same process in different ways. When an acquiring company and a target company use different processes, the processes must either be changed or the differences must be accepted and managed. Either alternative is expensive.

Comparing business organization models is also useful. The two companies are likely organized somewhat differently, perhaps very differently. And their interactions, both internally and with suppliers and customers, will differ. Assessing the extent of the differences is important to considering the costs of post-merger integration.

Comparing business rules can be useful. Business rules are certainly easier to change than other aspects of business architecture. If the target company operates under different business rules than the acquiring company, the rules can be changed. But rules can be easily changed only when the rules are managed separately from the business processes and the business applications. More typically, the rules are hidden deep inside software applications. If so, comparing business rules can only be performed by comparing the details of the applications.

Similarly, differences in business motivation are sometimes significant, and sometimes not so much. If the acquired company is willing to adapt to the goals and strategies of the acquiring company, differences in prior business motivation are not so important. But often there is resistance from the management of the acquired company. They want to continue using the strategies and tactics they know well. This leads to trouble. Understanding differences in motivation models can be important in identifying whether the acquired company is willing and able to change.

There are several different techniques for wringing business value from existing business models. Improvement analysis involves finding ways to improve a business. Transformation analysis is analyzing a proposed transformation to determine how to perform it. Impact analysis is considering a change and discovering and anticipating the consequences of the change. Acquisition analysis is examining a proposed merger or acquisition to determine the effort of merging the businesses.

The analysis techniques in this chapter are complemented by business simulation—the simulated running of a business model. Chapter 11 describes business simulation.

1For some acquisitions, no post-merger integration is performed. The acquired company is kept as a free-standing entity, and the two organizations and their business processes are not combined. But these acquisitions are a small minority. Most acquisitions lead to significant post-merger integration.

2Note that the Figure 10.8 process is the simpler customer dining process originally introduced in Chapter 2, not the more complex process—with subprocesses—from Chapter 5.