Chapter 1

Why Collaborative Enterprise Architecture?

Content

Goals and Benefits of Enterprise Architecture

The Gray Reality: Enterprise Architecture Failures

Between Success and Disappointment

Perspective: Between Bird’s-Eye View and Nitty-Gritty on the Ground

Governance: A Host of Directives, but No One Follows Them

Strategy: Marathon or 100 m Run?

Transformation: Between Standstill and Continuous Revolution

Reasons for this book

Enterprise architecture (EA) is often projected as a multipurpose medicine that cures an enterprise of all pains and problems. EA comes in different flavors—sometimes a marketing gimmick in management talks, sometimes a means to boast about knowledge of some framework or other, and sometimes an academic research topic. As a consequence, there seems to be a mystical mist surrounding the field of EA. This mist obscures the meaning and purpose of this field—not only for the naïve observer but also for the mature architect.

In our professional lives, we (the authors of this book) have approached EA from the ground up, coming from the basic levels of IT and software architecture. When EA groups were established in our organizations, we experienced both the benefits and the shortcomings of EA. When eventually taking over enterprise architect roles ourselves, we had our own sets of successes and blunders. Over the years and across different roles in the IT organization, we have become convinced that something as vitally necessary as EA should be organized in a more effective mode. This reorganization should appropriately involve all stakeholders in the decisions, including business users and developers, instead of acting out of an elite inner circle. It should adopt a more incremental mode of working and drop unnecessary bureaucracy in order to become more flexible.

The first time we came in touch with EA was about ten to fifteen years ago. We were, in separate companies, working as software architects at the project level. Shailendra was employed by an IT consulting company doing various projects for customers around the globe. At the same time, Stefan and Uwe were working in product development for a global network equipment provider. Still, our experiences with EA (both on the customer side and within our own organizations) were similar among all of us. There was often a mix of great expectations and disappointment in the actual result.

The need for an enterprise architecture was always plainly and painfully visible. In Stefan’s and Uwe’s company, the product lines behaved like independent principalities, each making its own technology platform decisions. A Not Invented Here1 mentality prevailed. In the same way, each line was responsible for its own product management. Therefore, the alignment between customers’ business needs and products’ features was handled in a quite fragmented way. The different software applications in the overall product portfolio were hardly interoperable. They had overlapping and competing features that were jealously guarded by their respective product managers.

When we, as architects responsible for one of these products, met customers, we often felt as though we’d drawn the shortest straw. “Why do we have to export the data from product X and import it to product Y in order to use it there, instead of just opening Y from X’s user interface?” asked the customer, and silently we had to agree with them. However, the situation on the customer side wasn’t any better. Not only did the customers’ different departments and business areas use different middleware (three different vendors, each in multiple versions, were nothing out of the ordinary); they also used separate sets of applications for the same tasks. This made system integration a challenging task for us when we had to build an integration platform, or deploy a business intelligence system that needed to draw data from virtually everywhere.

Given this evident lack of coordination amongst the software applications and between the application portfolio and the business needs, we often longed for a group of vigorous enterprise architects. They would ride in like the good guys in a Western movie and reinstitute order in a world of anarchy. And indeed, gradually we noticed the rise of an EA culture. EA groups were formed in the customer organizations as well as in Stefan’s and Uwe’s product development organization. But, alas, it was not the band of superheroes we had hoped for.

For each sensible move toward synergy and technology harmonization, there were also a few mindless decisions imposed on us from above. This, at least, was how we perceived the situation. In one of Shailendra’s projects, the project architects had proposed Oracle for a data volume expected to be in the terabyte range. The customer’s newly formed EA group, however, had just declared Microsoft the strategic vendor. They insisted on SQL Server for the project, which (in the version available at that time) Shailendra’s team considered quite ill suited for such a large data volume. He had a very hard time talking the enterprise architects out of their decision.

In another project, where Uwe served as the lead architect, the EA group insisted on being the only design body for services deployed to the enterprise service bus (ESB). This meant a considerable risk of delays for the project. First, one had to reserve time with an enterprise architect for doing the service design, and then one had to subordinate to the fixed three-month release cycle of the ESB. In addition, the quality of delivered service design was often debatable. No wonder that projects usually tried to avoid using the ESB at all and chose other—often less suitable—middleware options instead.

Over the years we started to take over responsibility in the enterprise architecture area ourselves—as platform architects, in consulting assignments, or, in Shailendra’s case, as practice head for enterprise architecture within the company. Evidently we did a decent job, by and large, since each of us was granted more and more responsibility over time. However, we had ample opportunity to ourselves commit some of the blunders we had previously observed in EA groups. And we made full use of this opportunity:

• We steadfastly defended our own holy cows—insisting, for example, that everything should be modeled as a Java Enterprise Edition (JEE) entity bean and that stored procedures are impure. We tried to push the usage of our enterprise platforms by extensive micro-management and were surprised and embittered about the resistance from projects.

• Harmonization and integration of competing base platforms were activities we repeatedly, and with much heart, engaged in—often enough seeing in the end that integration projects were way too expensive to be realized or were no longer needed from a business perspective one year later.

• Designing a model-driven common middleware mediation layer, we yielded to the temptation of using highly complex meta- (and meta-meta-) models that were supposed to cover each and every foreseeable extension—only to fail with a simple side requirement coming in one month later.

• We repeatedly spent months on writing extensive IT strategy papers, only to discover in the formal review meetings that no one had read them. Those stakeholders whose opinion really counted hadn’t even turned up.

• Often enough, we talked until we were blue in the face to convince different (and bitterly competing) business groups to come to an agreement on a shared application platform, shared data model, or shared infrastructure. Frequently such mediation was a wasted effort. None of the stakeholder groups was willing (or able) to compromise on its own unique requirements and service-level expectations.

The list could be continued further. On top of all that, we (of course) always believed ourselves to be right—at least at the time a decision was made. Assuming that we are not stupider than other architects, what could be the reason for such suboptimal outcomes? After exhaustive analysis and many discussions, we found that each of the previously described situations boiled down to people issues. These issues can be characterized by lack of interaction and communication, resistance to leaving the ivory tower, failure to involve the right stakeholders, specification as an end in itself, and so on.

Such behavior is human and occurs even among the most highly skilled individuals. The countermeasure is not attempting to change people. This will not work. The most effective remedy is to change the way of collaboration, the rules for interaction, and the organization structure.

We had seen techniques for making that work outside our architecture domain. As project architects, we had applied lean and agile methods for years. We had helped produce software in an incremental way, on time, and of good quality. The agile methodology involves all stakeholders on a regular basis and focuses on producing usable results within a fixed heartbeat. Lean practices avoid wasteful activities and help concentrate on the need at hand.

In addition, we had dealt with Web 2.0 and Enterprise 2.02 concepts in a couple of projects and had seen how well they, if properly used, can leverage the wisdom of crowds for decision making.

Couldn’t these techniques also be applied to enterprise architecture? Are they appropriate for such a dignified, long-term oriented, and elitist discipline? Against a backdrop of the discussions, lectures, consulting assignments, and trials we have undertaken in recent years, we answer these questions with a clear Yes. In writing this book, we attempt to elaborate our view on the current best practices of enterprise architecture and how those practices can be enriched by lean, agile, and Enterprise 2.0 concepts.

Our effort in writing this book is a consequence of our desire to steer away from the mystical mist that surrounds EA, as we mentioned in the beginning of this chapter. We want clarity—as vivid and as realistic a picture of enterprise architecture as possible. We want to make practical sense of EA and make it more meaningful to use—for ourselves, for our fellow IT practitioners, and for managers. And we want to explore new, pragmatic ways of practicing EA that will work well in today’s rapidly changing business world.

We will consider ourselves successful if you, the reader, can zealously and successfully translate our proposals outlined in this book into your own way of dealing with enterprise architecture. You are invited to follow us into EA as a realm of high-flying goals and humble reality—and then further toward pragmatic improvements.

Goals and benefits of enterprise architecture

We open this section with a little story. It illustrates in a nutshell, and in a somewhat idealized way, what targets EA should fulfill. It talks about enterprise architecture against the backdrop of a leading global bank, Bank4Us.

Bank4Us is a fictitious bank, yet its story reflects the realities of a typical large enterprise in today’s global environment. We will meet various members of the Bank4Us staff—managers, enterprise architects, IT experts—in this and coming chapters. Bank4Us will serve as a common theme running throughout this book, illustrating how an IT organization can implement a collaborative EA. (We have listed the employees we will accompany in the Appendix, “The Bank4Us Staff,” including a brief description of their roles, so in case you lose track of the players you can look them up there.)

The world of banking is changing rapidly: Customers are difficult to acquire and retain; competitor initiatives, coupled with economic recession, are eroding banks’ market shares; technology-driven avenues for business growth are available but not yet tapped effectively. In response to this difficult market situation, the CEO of Bank4Us issues a vision statement that clearly underscores the bank’s priority number one:

Best-in-Class Customer Experience: Anywhere, Anytime, Any Channel

A new business transformation program named “Closer to Customer” is initiated. During the annual strategic planning sessions of the bank, Dave Callaghan, the bank’s CIO, confirms his commitment to the CEO vision:

Our IT will act as a transformation engine to take the bank “Closer to Customer”—step by step. While we expect a business growth of 150% over the next five years, we will restrict the IT growth to 60% of our current investment level. We will adopt a “20/20” strategy, meaning 20% savings and 20% value addition. The savings will be attributed to legacy reduction/downsizing, reduction in number of system interactions, and reduction in IT operation/support cost. The value addition, on the other hand, will be achieved by customer empowerment, customer satisfaction, operational efficiency, and shorter time cycles.

Sarah Taylor, a program manager at Bank4Us, is unsure how Dave is going to fulfill these promises, given the current state of the bank’s IT environment. Sarah has only recently joined the bank and is responsible for managing an application portfolio of 62 IT systems. These systems support the customer management platform for the retail line of business, one of a total of five business lines. At this point Sarah has only a rough idea about the bank’s overall IT landscape.

To her knowledge, the total application portfolio consists of more than 3,000 applications, including around 600 aging legacy systems (systems with more than 10 years in a live environment). There is a significant functional overlap among these applications: For example, there are as many as 30 account-opening systems, more than 10 authentication systems, more than 20 credit decision engines, and almost 40 business intelligence tools.

The supporting technology infrastructure is equally complex. It includes more than 2,000 server machines hosting 20 versions of five operating systems. There are more than 10 database platforms and roughly 25 middleware platforms, with as many as 35 programming languages in use. The scale and complexity of the IT landscape is further aggravated by a large number of system interactions—some of them apparent, but most of them buried under the heap of heterogeneous technology platforms.

In this jungle of IT systems, Sarah already finds it difficult to control her portfolio of a mere 62 systems. She has the feeling that her knowledge about her own portfolio is quite limited and superficial at best, or grossly incorrect and outdated at worst. She does not dare deduce her own goals from the CIO’s commitments. As impressed as Sarah is by Dave’s confidence, all the more she is worried about the mandate set forth for the IT organization and its consequences for her own job. When Sarah discusses her concern with her supervisor, he advises her to speak to Ian Miller, an enterprise architect.

Ian is a member of the bank’s EA group and will collaborate with Sarah on the architectural work related to the customer management area. The EA team at Bank4Us has existed for a couple of years now. Last year a new chief architect, Oscar Salgado, was appointed head of the team. Since then the EA team has been seeking to play a more proactive role in the business-IT interaction and is becoming more visible in the enterprise.

So, what is Ian expected to do? Ian was instrumental in crafting the CIO’s mission and strategy based on the priorities of the business. He will be responsible for helping Sarah establish her project portfolio in alignment with the defined mission and strategy. He is supposed to sketch the complete picture of the IT landscape, show Sarah how the CIO’s mission links to the IT landscape. Ian will also have to demonstrate how the planned projects will take the current IT landscape to the envisaged state over a period of time. He will explain to Sarah what that means for the business and, more specifically, how it influences her scope of work. After the project-planning phase, he is also committed to guiding her project teams so that the desired goals are met and expected benefits are realized.

In addition to Sarah, many more individuals and groups inside the bank organization need to be told the same story about the bank’s IT landscape. Hence Ian and his team will consistently communicate with all the concerned parties in such a way that they can understand the information presented and act accordingly. In essence, Ian’s task list and job description reflects what enterprise architecture is all about. It ensures that the enterprise IT landscape moves in the right direction to fulfill the strategic goals of the enterprise.

The Enterprise Architect

The Mandate of an Enterprise Architect

Information technology (IT) is a fairly young field compared to many other industry sectors. IT has been used in mainstream business for only 50-odd years. Over the last few decades, IT has made a startling impact on the way enterprises do business. As enterprises started relying more and more on IT to support their day-to-day business operations and to enable their long-term business strategies, the role and contribution of IT in the enterprise gained more and more importance. With a continuous addition of new applications, prolonged retention of legacy platforms, and a growing number of system interactions, the enterprise IT landscape has gradually reached a remarkable level of complexity. Apart from incurring heavy costs, this complexity impedes business changes and therefore causes frustration among business people. For business, IT is an asset and a liability at the same time. Broadbent and Kitzis (2003) characterize this reality as “IT has fallen victim of its own success.”

So, what does this reality mean for an enterprise architect? In a very condensed form, it puts forth the following mandate for EA architects:

Controlling IT complexity

The answer to the most basic question, “What is it that enterprises want from IT?” is consistently the same across all industries. The answer is, “Enterprises want their IT to be stable, agile, adaptable, and efficient.” Now, what does that mean?

• Stable. Reliable, resilient, available and fault-tolerant.

• Agile. Enable quick introduction of new products, services, and business processes; be responsive to market dynamics and customer needs.

• Adaptable. Adapt easily to different business contexts, regulations, mergers and acquisitions, and convergences.

• Efficient. Meet or exceed business and service-level expectations; minimize total cost of operations.

Unfortunately for IT, these noble goals are a far cry from reality today. IT invariably remains brittle, sluggish, inflexible, and expensive. This nuisance of IT is, in most enterprises, a compounding effect of the complexities originating from many sources:

• Immaturity in software engineering

• An uncontrolled proliferation in the IT landscape (sometimes dressed as lack of organizational ownership in IT)

The prime reason for IT complexity is the inherent complexity of business itself. A typical global enterprise like Bank4Us in our example operates in a highly volatile market environment. Apart from supporting local customer demands and market regulations, enterprises must also respond to competitor challenges and market opportunities. In addition, they must keep pace with the emerging technology landscape and introduce innovation in performing their business tasks. To fulfill the myriad of such demands, an accelerating train of changes runs though the enterprise. These changes take place on different planes:

• Business. Changes in the business context (such as regulation, mergers and acquisitions, or the competitive landscape), new business models, new business products and processes, or new customer demands.

• Technology. Changes in the technology strategy (technology usage, vendor preference, new technology integration, legacy retirement, out-of-support software, server consolidation, license optimization, maintenance and upgrade), workload changes due to user and volume growth, or updated service-level expectations.

For Sarah’s portfolio of customer management systems in Bank4Us, the business challenges mainly manifest themselves as new business models and new customer demands. They invariably require a high level of synchronization between the five business lines. With regard to technology, Sarah faces the inevitable pains when it comes to version upgrades of the middleware platforms her applications are based on. However, Bank4Us’s EA team has in the past done a good job of keeping the technology strategy stable. So at least she doesn’t yet have to go through the adventure of migrating between two different middleware implementations.

The immaturity of software engineering practices also contributes to IT complexity. In comparison to other engineering disciplines such as mechanical or civil engineering, the field of software engineering is quite young. The design, development, and operational processes are not yet as mature as those in traditional engineering disciplines. Despite the high-handed quality promises of software vendors, system integrators, and other players in the IT market, the reality on the ground often relies on improvisation rather than rigidly followed formal processes. Frequently, enhancements and quick fixes are introduced to operational systems in an ad hoc manner—sometimes to meet delivery commitments, sometimes in response to emergency situations.

In other disciplines, the engineering of a product comes to an end once it is shipped to the customer for use. From then on it is never redesigned or rebuilt. Once a compact family car has been manufactured, for example, it will not be upgraded to a convertible sports car. In contrast, IT systems are enhanced continuously while they are in use. Often something like the conversion from a family car to a sports car is actually attempted in IT—though not always successfully.

For Sarah, this inherent process immaturity is a constant challenge in every IT project. Her applications are customer-facing and are used across multiple time zones. Therefore, only a minimal downtime for redeployment is permissible. Furthermore, the testing procedures require a high amount of rigor. Sarah’s worst nightmare is the proverbial call from the CIO’s office in the middle of the night, enquiring why UK customers cannot access their account details. Fortunately, this situation has not happened yet.

To a great extent, IT complexity is also the result of an uncontrolled proliferation of redundant IT systems, caused by the IT organization’s tendency to follow a stovepipe system integration style. In an enterprise with silo-based organizational partitions, each business unit typically has its own IT budget; therefore it will go its own way in procuring, building, and operating its IT systems.

In addition, IT departments are normally organized on a project (or a product) basis. The project teams decide everything locally. This is a trade-off: It allows for independence, agility, flexibility, and efficiency in the local environment, but it prevents leveraging enterprise-wide synergies. A large number of tactical and parallel IT systems mushroom up into different parts of the enterprise, often leading to a nearly unmanageable jungle of redundant applications and data stores.

System redundancy is, in our Bank4Us example, not much of a concern for Sarah. She sometimes regrets not having closer cooperation with her program management peers in other units, though, since that might be helpful in addressing common issues. For the enterprise architect Ian Miller, however, the redundancy causes more of a headache. For example, customer management systems are scattered across five different business units and therefore (because IT is organized mirroring the business) are spread over five different IT departments. If Ian needs to address issues with customer management systems, he also needs to talk to four other program managers besides Sarah and facilitate common ground among them.

The ever-expanding cosmos of enterprise IT is becoming more and more complex. An enterprise architect must safeguard IT as a corporate asset. The cost must be justified by what IT delivers. This means that every opportunity to eliminate needless complexity and costs in the IT landscape must be spotted and leveraged. In addition, the enterprise architect must make sure that every new addition or change to the IT landscape is justified by an agreed business purpose and that it has a committed business value.

EA provides guidance about what technologies are a strategic fit, which ones are deprecated, and which are emerging. The project managers on the ground need that input in order to take decisions on turning off legacy platforms, merging redundant applications, or introducing new systems—in effect, simplifying the IT landscape. The benefits may be realized in terms of:

• Improved business confidence3

In essence, EA is a hygiene factor for the IT landscape.

Ian Miller, in our Bank4Us example, needs to facilitate the implementation of the CIO’s mission statement. In his role as enterprise architect, he plans the first steps toward the cost-saving goal. First, he needs to get up-to-date information on the current costs of the applications in the IT landscape. The last survey conducted by Ian’s predecessor is already more than two years old. It can serve as starting point, but Ian decides that it needs an update. In addition, he needs to understand which applications are used for what purpose. He would like to see a mapping of the business processes against the applications so that he can identify redundancies. Luckily enough, the business processes have been modeled only recently and can be assumed to be fairly up to date.

Ian decides to make appointments with his main stakeholders before proceeding any further. One of his first meetings will be with Sarah. Since Ian has not only his CIO’s cost-saving target to fulfill but also has the CEO’s vision of a more customer-oriented focus in mind, Ian also needs Sarah’s input on how well the current IT landscape supports customer orientation.

Aligning business and IT

The world of business is rapidly evolving; customers are demanding more sophisticated products and better services. The convergence of communication and computing is opening up avenues for new business models and revenue streams. The IT systems must support new ways of doing business collaboratively with partners and customers. The result is a “multi-entity” ecosystem that allows interaction at more touchpoints and a depth not previously attempted.

Today’s business challenges are not going to be met by simply adding a few systems here and there nor by tidying up a few platforms in the enterprise IT landscape. The only solution may be to completely restructure the enterprise’s operational and organizational regime in the new environment. It will be a transformational journey that has to start with EA.

The goal of enterprise architecture is to act as a guide, perhaps a pathfinder, who takes the enterprise on a transformational journey—from an incoherent and complex world with line-of-business separation, product-specific stovepipes, legacy systems estate, and costly operation to a more rationally organized and useful state with multiservice, revenue-generating platforms and an efficient operational regime. On the way, radical surgeries may be required to eliminate duplication, reduce costs, improve reliability, and increase agility in the business. EA acts as a strategic foundation for business enablement.

The transformational journey that begins with EA is long and hard. The effort may be cost-justified by identifying IT-centric benefits, but the real value of enterprise architecture can only be appreciated when it delivers tangible business benefits.

The enterprise architect must envision how EA will change the way the enterprise operates and how large the generated business benefits will be to outweigh the effort spent. The benefits must be realized in view of both long-term and short-term business priorities. For instance, when embarking on a multiyear plan for the deployment of a unified, strategic service-oriented architecture (SOA) platform for the enterprise, the business should be able to see the benefits of such a platform early enough (say, within the first six months) and then periodically thereafter (for instance, every three months).

In Bank4Us, the EA initiative “Closer to Customer” is geared toward delivering the following strategic business benefits:

• Customer empowerment. Customers should be enabled to manage their own banking environments (in buzzword lingo: “self-service, zero-touch, in real time”).

• Customer intimacy. The IT systems should provide personalized customer service based on an intimate knowledge of the customer’s needs, behavior, and lifestyle.

• Customer satisfaction. Operational synergies across the different lines of business should be leveraged to reduce the cycle time and failure rate in all customer interaction processes; that will help implement a true single face to customer concept.

• Customer excitement. Finally, the customers should be excited by innovative products and services. This allows the bank to respond to competitor initiatives and market opportunities in an agile fashion and to be the first in the market (or at least an early follower).

This list brings an interesting pile of activities for Ian. The starting point for any major activity in the bank is a business case; this has to be driven from the business side. Ian plans to participate in its creation process in order to understand the broader business perspective of the “Closer to Customer” initiative and to keep track of the big picture of the bank in his mind. Over a period of some weeks, he confers with various business stakeholders. One of them founds an informal working group with several other business managers and invites Ian to participate as a member of the EA team. The group begins with the preparation of the business case document for harmonizing the key customer-facing business processes across the five business lines of the bank.

The business case refers to the process maps for three customer-facing business processes:

The case further highlights that the processes are, to an extent, similar across all business lines. There is about 30% commonality, but there’s also a potential for much more standardization across the business lines. The business stakeholders estimate that the processes could even be unified to a degree of 80%.

As a next step, the business case also looks at the customer satisfaction goal that requires reducing the cycle times and failure rates in these customer-facing business processes. It explores the possibilities to measure the cycle time for the processes in an automated way. This would allow the business to effectively monitor and optimize the end-to-end process time in the future. It also identifies common failures and their effects in these processes. After many discussions, and by taking an active support role in compiling a business case and supporting documentation, Ian gains a decent understanding of the high-level business requirements.

Ian prepares an IT proposition in response to the business case documentation. The proposition highlights opportunities for process harmonization, data standardization, and capability reuse in the bank’s operating IT environment. In addition, Ian gives a recommendation to the sponsors as to how they could monitor and optimize the customer-facing processes for minimum cycle time and straight-through processing with the help of available technologies. He gets his proposition vetted by Sarah and her peers and finalizes it for discussion with the sponsors and users on the business side.

Ian is wary from the litany of unsuccessful enterprise resource planning (ERP), customer relationship management (CRM), and similar IT-inspired programs. He has come to realize that IT alone is not enough to bring about a transformation. If the business leaders do not share ownership of both the implementation and the outcome, the path to IT transformation will be a disastrous journey. On the other hand, the business can neither simply rely on IT nor lead IT-enabled transformations. Hence the business expects IT to step up to the task.

For that purpose, Ian manages to involve CIO Dave Callaghan via his boss, the chief architect. Ian asks Dave to first generate a widespread agreement among business leaders as to the appropriateness of the CEO’s vision and the IT-enabled transformation. Dave, in partnership with his counterparts on the business side, assures a joint ownership for the transformation. This step helps to get the program staffed adequately so that the necessary expertise is available on both the business side and the IT side. Dave now formally sets up a joint working group between IT and business and assigns Ian, Sarah, and others to that group.

As a next step, Ian participates in the brainstorming sessions with the subject matter experts from business and IT across the five business lines in order to review his proposition and resolve issues raised by the stakeholders. He applies some changes to his document to accommodate the stakeholder needs. This is the most challenging exercise that demands deep collaboration among all stakeholders, who come from different professional backgrounds and organizational cultures and may even have competing priorities. Luckily, the essence of Ian’s ideas has survived this crucial process. He now expects Sarah and her peers to budget and plan further for this initiative.

Once the initiative has been approved, Ian takes this effort forward by working closely with Sarah and her peers. Jointly they identify those capabilities they can use from existing systems versus those they will need to buy or build anew. In the process, Ian looks at opportunities to maximize the reuse of applications, data, and infrastructure. He guides the project architects in defining the solution architecture and the deployment plan. Ian also identifies the initiatives that will enable change and bring in new technologies, if needed. Eventually Ian has to guide and govern the project implementation to make sure the intended outcome is achieved.

Whether EA is perceived as a hygiene factor for the IT landscape or as a strategic foundation for business enablement, it is obliged to deliver value. As a hygiene factor, benefits from EA can be valued in terms of reduction in management escalations, emergency occurrences, and year-on-year operational expenses. As a strategic foundation, EA facilitates the deployment of new capabilities. This way it helps IT gain more business trust—and hence more funding for new IT projects. Unfortunately, these benefits are difficult to quantify on a short-term base. Therefore they need to be tracked over a sufficient time period and then be normalized to a common baseline. Only then can they serve as a sensible benchmark for measuring the success of EA.

This is just a brief snapshot of EA activities. We will delve into the details in Chapters 2 through 5, where we present a more thorough definition of EA and give an overview of the practical activities, methods, and concepts it involves. For now, this overview should suffice to give you an impression of what the job of an enterprise architect comprises.

Bank4Us is not an enterprise architect’s wonderland, but by and large EA is still able to perform its tasks. The practice on the ground is often more complex and less well organized than depicted in the story of Ian and Sarah, at least in many enterprises. Let’s now look at this less glossy reality.

The gray reality: Enterprise architecture failures

Everyone is a moon, and has a dark side which he never shows to anybody.

—Mark Twain4

In the previous section, we outlined how EA is supposed to function. For many enterprises this is a somewhat idealized picture. The real Ians and Sarahs of this world often do not meet regularly, sometimes look down on each other, or in the worst case, rarely ever talk.

In our jobs as architects and consultants, we have seen quite a few enterprises from the inside over the past few years. We have seen a large firm, where the absence of an effective EA yielded shortcomings across all organizational units in touch with IT:

• Business managers who had no clear conception of how their business unit is utilizing IT

• Technical application owners who did not know which systems their application was interfacing with

• Developers who felt uncertain about which framework to use (and consequentially downloaded whatever they felt suitable from the Internet)

• Operational staff who desperately experimented with restarting a bunch of information systems in production because they had no idea about their interdependencies

On the other hand, we encountered companies that, despite having a fully institutionalized EA in place, were in a state close to paralysis. The conglomerate of business, organizational, and technical dependencies had grown to a muddle that made reasonable changes impossible. As a consequence, these companies were still able to operate their existing IT assets for daily work, but they were unable to move in any direction toward the future. They had usually gone through several not-so-successful application rationalization attempts over the years.

In one such case, the only possible way to find out whether an application was not in use anymore and could therefore be actually ramped down was to literally place a red phone beneath the hosting server and then shut down the server. If no angry calls came through for a period of one month, the conclusion that no one needed the application anymore was considered safe. Everyone can draw his or her own conclusions on such an approach.

IT transformations being cancelled, a wrong portfolio of initiatives taken up, totally overambitious harmonization programs, anarchy due to ineffective governance—the list of possible IT blunders could easily be prolonged further. The reasons for such problems are usually manifold, of course, and cannot be pinned down to malfunctioning enterprise architecture alone. However, as we saw in the previous section, EA is supposed to prevent such failures—so why do they keep happening?

Let’s take a closer look at the situations in which EA is not living up to its promises, then attempt an analysis of the reasons why not.

Between success and disappointment

Although EA has reached the mainstream, a skeptical undertone with regard to its effectiveness has always existed. In 2004, after completing many years of EA effort, the General Accounting Office (GAO)5 reported a standstill in EA maturity within US government agencies: “Of the 93 agencies that we reported on in 2001 and 2003, 22 agencies (…) increased their maturity, 24 (…) decreased their maturity, and 47 (…) remained the same” (U.S. GAO, 2004, p. 27). In another account, an online survey revealed that the overwhelming majority of participants doubt the success of EA programs, at least within the first couple of years (Spacey, 2011).6

EA has not yet fully proven that it provides tangible business benefits in the same way that other enterprise functions do, compared to the effort and cost it accumulates. Although EA is all about business-IT alignment, it is historically an offshoot of the IT organization. Often enough it is a part of the IT organization and run by IT people, with only marginal participation from the business side.7 Even if the real business problems are actually addressed, the cost-benefit justification is often IT-centric and fuzzy. It is based on the perceived value of architecture rather than using a viable proof point about the actual business value delivered in a real-life scenario. The business sponsors, however, want to know what EA actually delivers, not what it “could” deliver.

Does that mean that EA, in its current form, is too amateur to meet the needs of the time? Of course, our answer is No—otherwise we would not have written this book. But neither is it the shining white knight who renders all criticism obsolete. EA is needed and useful. But the way it is practiced today still has shortcomings that should be resolved in order to boost its universal acceptance.

Adopting a harsh critic’s perspective, one could claim today that:

• EA does not scale to create any visible impact in a large enterprise setup.

• EA is not equipped with the right approach and toolset to cover the entire scope of work, from strategy through implementation.

• EA fails to keep pace with the speed of change in modern business.

Yet, according to literature and our own experience, spectacular failures happen only in a minority of EA programs. As a general rule, case studies documenting the effect of an EA program—whether success or failure—seem to be rare. Especially we have not found any documented cases where EA programs have actually been cancelled and the EA organization disbanded. More often, EA seems to slip into a gray mediocrity: Fulfilling some promises but failing others. An EA organization working in this mode is still too lively to be abandoned but does not have enough strength to effectively set the course for the whole IT organization.

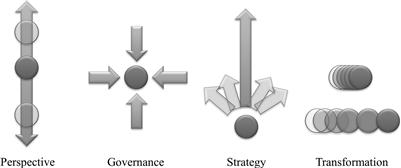

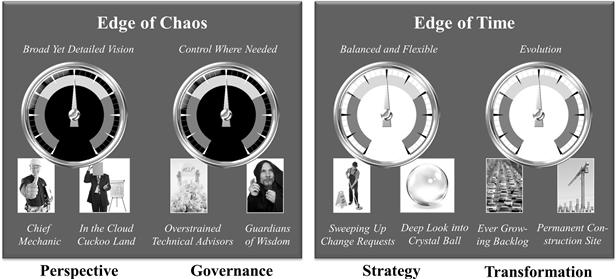

We will take a closer look at the challenges and failures of EA in the coming sections. The four dimensions depicted in Figure 1-1 will serve as a structure for our analysis. We will come back to them later, when describing building blocks for a collaborative EA, designed to tackle the identified EA problems:

Figure 1-1 Dimensions for analyzing EA challenges and failures.

• Perspective. What viewpoint does the EA group take? Does it prefer a “helicopter perspective” with little involvement in the hands-on IT business, or do its members involve themselves knee-deep in concrete architecture work in programs and projects?

• Governance. How strict is the adherence to, and enforcement of, rules set up by the EA group? Does the organization follow a laissez-faire approach, where each project has a high level of freedom, or is a rigorous control system in place to supervise compliance?

• Strategy. To what extent does the EA group focus on strategic planning, and what is the typical time horizon of the plans? Does EA follow the one “great vision,” or—at the other extreme—is there no long-term planning at all?

• Transformation. What is the speed of change in the landscape of business models, processes, and IT systems? What kind of IT transformations are taken up?

We have condensed some of the more frequent practical EA anti-patterns (collected from own experience, some expert interviews, and material documented in literature8) into eight EA caricatures interspersed in the following text and summed up in Table 1-1. The caricatures match the extreme positions in each dimension. They exaggerate reality to bring out the essence of the problem more clearly.

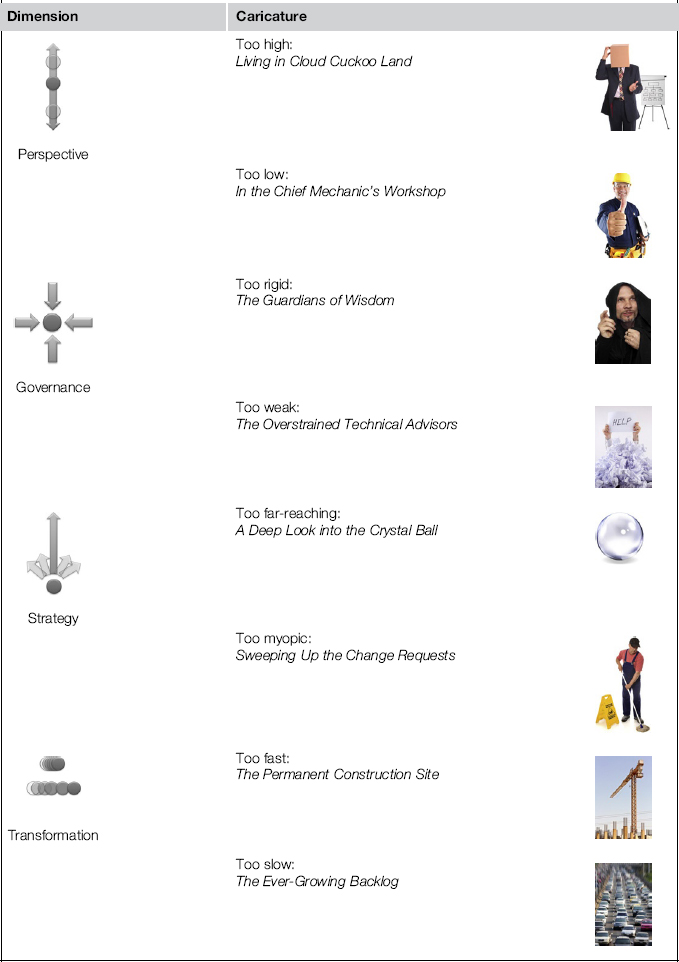

Table 1-1 Caricatures of Enterprise Architecture

In each dimension, the EA group should find its proper position between the extremes. This does not guarantee a catch-all solution as to how to do EA properly, but it provides a grid to classify the most common problems. No EA group will be a 100% version of a caricature—but so far, we have not encountered any organization that didn’t show at least some of its traits.

Perspective: Between bird’s-eye view and nitty-gritty on the ground

An Indian saying expresses that a bird flying high in the skies will always keep an eye on her babies in the nest down below. In comparison, what is the extent to which an enterprise architect looks at the concerns on the ground while flying high on the level of a corporate vision? A candid answer to this question reveals the degree to which the enterprise architect can succeed in translating a vision to a venture.

![]()

Enterprise architecture is predominantly approached through a top-down way of thinking: First articulate the corporate vision, then define key objectives and progressively drill down into the further details of implementation. The vision will help bring all stakeholders across all organizational silos of the enterprise under one common roof, and will motivate the entire workforce to reach for that vision. All the subsequent objectives, targets, projects, and activities can be derived from the vision and must lead toward the vision. At least in theory, this is how it EA is supposed to work.

We have encountered many examples whereby this process is less straightforward. An application rationalization project of a global logistics company was run under the maxim of considerably reducing the numbers of applications and application platforms in order to serve the corporate mandate: save costs. Among the concrete measures identified by the EA team was the global replacement of a parcel-tracking application by an already existing Web-based system. The planning had been finalized, and the budget was allocated.

Then a series of letters was sent to the country heads, announcing that the legacy tracking application was about to be replaced by the Web interface. You can imagine the surprise in the EA group when the Italian country head wrote a letter back, asking sarcastically if the IT department would also pay for a couple of thousand iPads. As it turned out, the handhelds that the logistics drivers in his region used were incapable of running a Web browser. No one on the EA team had known that.

This may be an isolated example, but it illustrates a general problem with regard to EA. On one side, an enterprise architect is expected to have a broad overview of both the IT and the business landscapes. On the other side, the enterprise architect needs to retain her grip on the details of business and technology to such an extent that she still understands the reality on the ground. This is a wide chasm that’s not always easy to bridge.

Perspective Caricatures

Caricature #1: Living in Cloud Cuckoo Land

When an enterprise architect is too decoupled from the community of project architects and developers, she loses insight into the challenges of the IT projects on the ground. A similar gap can exist between the enterprise architect and the users of applications and processes on the business side. If the enterprise architect does not bother to ask the end users how well suited a process is, she is likely to evaluate the as-is process landscape in the wrong way. An EA organization in Cloud Cuckoo Land is ignored or circumvented by both the IT and business departments on the ground.

One possible symptom of Cloud Cuckoo Land is a tendency to focus on the big picture. The big picture is part of the standard mindset of EA, which everyone immediately associates with the activities of an enterprise architect. However, many of these big pictures you meet in practice have been over-abstracted to the point of insignificance and no longer address any relevant question.

In addition, the option for hierarchical search and semantic drill-in is often undermined by the loss of information between the abstraction layers. Semantic distortions are the rule rather than the exception. The main danger of such a kind of big picture is that it glosses over and obfuscates the gap of understanding between EA and IT management on one side and the IT reality on the ground on the other. This creates an atmosphere of false security at the corporate level and prevents triggering corrective actions.

EA entails making and following a set of policy decisions that steers the strategic direction for the evolution of IT. Often there is no one single “right” answer but a plethora of conflicting priorities and choices. The enterprise architect has to select those options that seem both most promising and least damaging at a given point in time. An example is the choice between the conflicting architectural priorities of performance, interoperability, and manageability. The right solution design for a certain type of application can look quite different for different enterprises. It can even vary at different points in time for the same business line of one enterprise.

If such policies are designed by an isolated group of experts with little bandwidth (and even less inclination to reach out to the people concerned by the consequences), EA is bound to run into a wide range of problems. Overlooking technical details can become far more costly than anticipated. “Architecture represents the significant design decisions that shape a system, where significant is measured by cost of change,” writes Booch (2006). A high-handed focusing on the big picture is prone to overlook some of the significant (i.e., expensive, in the sense of Booch’s definition) aspects of the solution.

The quoted example of not having Web-enabled handhelds for the logistics drivers would be, if it had not been detected in time, a good example of this risk. Another rich source of Cloud Cuckoo Land examples is the “naïve” way of implementing SOA, which was pretty common in the early days of this design pattern. The best example we found was the strict directive of the EA group of a logistics company to implement all data interchanges between systems as Web services—including a point-to-point connection that had previously been a nighttime batch job. It shovelled gigabytes of data through a web connection, including the transformation to and from XML.9

Another shortcoming of a top-down approach without sufficient grounding is that it may meet significant conscious or subconscious resistance in the people on whom such decisions are imposed. It is a trivial (yet surprisingly often disregarded) fact that the buy-in of co-workers can be neither taken for granted nor enforced by orders; it has to be earned by involving these people in the decision-making process.

So far, we have described the risks of a too detached and high-handed EA team. However, in the Perspective dimension the other extreme also exists and can be responsible for EA failures. An “old-school” type of CIO is firmly rooted in the IT department and focuses on maintaining the status quo: ensuring that the IT service-level agreements are kept and the costs are under control. An EA group operating in such an environment is prone to lack a quality that the Cloud Cuckoo Land variety has in abundance: broad vision. Decisions are taken from an IT-centric background, and there is little inclination to proactively approach the business and to position IT as an enabler for new business models and markets.

Perspective Caricatures

Caricature #2: In the Chief Mechanic’s Workshop

If the enterprise architect focuses too much on purely technical issues or works merely as project architect, she runs the risk of neglecting the broad view and is not taken seriously by the business. This promotes the perception of IT as a cost-driving commodity instead of a business enabler. The role of an EA organization is then likely to be reduced to achieve cost reduction by managing standards and conducting IT rationalizations.

Often in such a setup, the EA group consists of experts instead of generalists. Each enterprise architect is a one-track specialist with a narrow focus on specific technologies or business requirements (such as security, performance, or user interface and stability), and no one in the team has a holistic view of the enterprise IT landscape.

Broadbent and Kitzis (2004) coined the term chief technology mechanic for the CIO running the shop in the preceding caricature. Apart from an organizational structure that places the EA team too close to the IT department, such a setup may also have other reasons. Insufficient architectural skills can be one. Another possibility is that the IT landscape of an enterprise has grown to such complexity that no single person understands the whole of it or even the whole of one application. A chief architect of a car manufacturing company admitted that fact quite frankly—the enterprise was so large, so long in the market, and so riddled with poorly documented proprietary IT solutions that no single enterprise architect had the complete overview anymore. A holistic view of the enterprise’s IT landscape appears hardly possible under such circumstances.

An EA group working in such fashion, with too much focus on the details and too little attention to the broad vision, tends to manage only singular aspects of the system. It basically abandons EA’s claim to shape the IT landscape actively and capitulates in the face of complexity. EA effectively stops happening.

This situation drives IT into the passive role of a mere commodity. Commodities, however, are primarily perceived as cost drivers. Therefore the IT function will quickly find itself in an endless loop of cost reduction demands from the CEO. This leads to the “orange-squeezing effect,” as Keller (2006) describes it: IT has managed to reduce its budget by 20% this year, and the applications are still operable. So why not ask for another 20% reduction next year? In the long run, this cycle leads to a degradation of IT within the enterprise. It also threatens the CIO’s position. As Broadbent and Kitzis (2004) point out: Each enterprise needs electricity, but no one would think of establishing a chief officer of electricity on the board.

An EA group operating too much on the detail level will not be able to ensure the design of appropriate, business-aligned IT applications. We encountered a particularly good example of this at a global insurance company. Over the years, the company’s IT department had developed a costly, proprietary content management system for their intra- and extranet, targeted at supporting the specific editorial process prevailing in this enterprise. In an assessment of the enterprise portal landscape it became evident that no one had ever bothered to precisely model the editorial process that had been the starting point of the development. The IT department had simply implemented a solution they thought would fit the business needs—with the effect that no one, neither on the business side nor on the IT side, was happy with the outcome. This situation is primarily the result of poor requirements engineering in the development project, of course, but an EA group with sufficiently broad vision would have insisted on doing the business architecture first.

Another phenomenon typically to be observed in a rather technology-savvy EA organization is a tendency to implement its own proprietary platforms instead of just reusing tried and tested industry standards. In the course of our careers we have seen several custom enterprise UI frameworks, each tailored to a special use case in the particular enterprise that was overrated at best, nonexistent at worst. (As a general rule, each enterprise considers its UIs to follow a unique paradigm, and almost always this is a case of self-delusion.) Such a reinventing-the-wheel mindset is a risk that leads to a hard-to-control jungle of technologies and solutions.

In summary, neither the big picture nor attention to detail alone will ensure successful EA work. The enterprise architect needs to be like a helicopter pilot who is fighting forest fires. Flying too high, she will no longer see the fires. Flying too low or even moving on the ground all the time, she will never get a complete picture of how much fire there is in the whole of the woods. She needs to fly at a middle level—sometimes higher to get an overview, sometimes lower to analyze a particular patch, and sometimes she will have to land in order to fix things on the ground.

This requires a practical framework for structuring the EA activities on a day-to-day basis, supporting the enterprise architect’s workflow at all levels of operation and ensuring the participation of all stakeholders. The enterprise architect needs all the help she can get to master this tightrope walk.

Governance: A host of directives, but no one follows them

Any EA practice that has existed for some time has accumulated a vast amount of knowledge comprising a multitude of principles, policies, procedures, practices, techniques, lessons, and so forth. Depending on the organization’s style, this knowledge is enforced with more or less vigor. That, however, does not guarantee the practical relevance of this knowledge. Often EA principles are perceived as a veritable nuisance by the practitioners on the ground.

We were involved in the development of a Web-based workflow system for a reinsurance company. The project architect had proposed to use an industry-standard Web framework supporting page flow and transaction management in a very suitable way. The framework was in use in other systems within the company as well and was on the list of accepted technologies. Still, the EA group insisted on the proprietary standard user interface platform, which would have meant at least 50% more effort and a hefty project delay. Only after an escalation to C level was the project architect allowed to continue with the original choice.

Many EA-originated policies that appear obsolete today have not always been meaningless. Most probably they have emerged as the architecture group’s overreactions to unlikely-to-recur situations that they experienced in their organization in the past. A frequent example is the uncontrolled proliferation of newly hyped technologies by the IT crowd, and the EA group’s rigid attempt to reinstitute order. Once the technology has matured, the EA rules often appear overly strict and suppress a flexible use of the appropriate technology.

As time passes, policies tend to become stale. Given the unpredictable and rapid changes that happened over the last decade, it is obvious that many of them do not carry much prominence today. Nonetheless, they still continue to be part and parcel of enterprise architecture. EA should therefore also continuously check and revise its policies.

Governance Caricatures

Caricature #3: The Guardians of Wisdom

Sometimes the EA organization has an overly rigid approach to enforcing its own standards. Instead of discussing a sensible level of standardization with the IT crowd on the ground, enterprise architects invest their energy in political fights for IT standards that are irrelevant at best and that stall creativity at worst. Examples of standards with the risk of being applied in an overly strict manner are the exclusive use of SOAP-based Web services as a data exchange protocol for all kinds of internal and external interfaces, or a certain UI platform prescribed for all clients.

In addition, if enterprise architects claim to be the only decision-making body in technical matters, there is a huge risk that they create a bottleneck. If decisions take ages due to pending strategic issues, imminent changes in the business model, and so forth, IT projects can be seriously delayed. The practical consequence is that projects deliberately circumvent the enterprise architects—for example, by choosing less suitable technologies not managed by the EA group.

Simple Object Access Protocol (SOAP) is an XML-based information exchange protocol used in web service implementation.

An overly rigid EA governance is prone to producing a rampant bureaucracy of approvals and sign-offs. From experience we know that a sign-off rarely means that the matter is really closed. The approved document is usually not questioned or openly disregarded. Instead, the reality on the ground—in the IT department, in the projects implementing parts of an IT transformation—slowly creeps away from the documented status. The predominant effect reached by too much focus on formal governance is that the EA group and the executors on the ground just stop talking to each other. The EA group thinks everything is settled in their sense, and the practitioners are happy to have the EA guys off their back.

The preceding caricature, the Guardians of Wisdom, paints a picture of an EA group whose extensive controlling attitude borders on micro-managing the developers. The other extreme is an EA team that is notoriously understaffed, overstretched, and invisible. Here the governance is not rigid but nearly nonexistent. Strangely enough, the consequences of both extremes are so similar that they actually represent two sides of the same coin. A distorted governance—too strict or too weak—leads to a situation where the EA group is not taken seriously and is unable to reach out to its stakeholders and therefore ultimately fails to fulfill its mission.

Governance Caricatures

Caricature #4: The Overstrained Technical Advisors

If the enterprise architect is completely lost in an everlasting struggle against the entropy of business and technology change, no IT strategy worth its name will ever evolve. This is often the case in a hopelessly understaffed or under-empowered EA organization. The enterprise architect is taken hostage by a business that forever demands solutions right here, right now.

To catch up with the pace of business changes, the EA organization is permanently robbing Peter to pay Paul. In such a setup, the EA group does not manage to establish standards that are actually followed within the organization. The enterprise architect is in high demand by the business and the projects to act as the “useful idiot” who can help out in defending technical problems. He is a good-to-have advisor at best and a not-to-have auditor at worst.

The result of distorted governance is usually some kind of anarchy on the ground. Patterns like the Not Invented Here syndrome prevail. Under a weak EA governance, it can be found in all parts of the enterprise, from business over IT department to even the EA group itself. Business departments usually favor custom-tailored solutions over reusing a company-wide platform. IT projects often ignore enterprise standards for technologies and platforms, blaming them as unsuitable for their task at hand.10

Lack of governance can cause substantial risks, which are usually not recognized by the decision makers. In the case of a global insurance company, for instance, no book of standards was in place for the use of open source components. Every developer basically just downloaded the frameworks needed for his or her task at hand. No legal checks were conducted, not even a centralized systematic tracking of the open source components in use. One simply needs to take a look at the great legal battles around Linux and Hibernate11 to understand the possible financial implications of such a laissez-faire policy.

The decisions made by the overstretched and ineffective EA group painted in the Overstrained Technical Advisors are often neither well documented nor properly communicated. The business and IT stakeholders on the field rarely learn about those decisions in the first place. Even if they do get to know them, they hardly understand what analysis has gone into making those decisions.

In such a process, a talented team of architects leaves nothing behind but a pile of architectural models that cannot be adapted, used, or extended, simply because no one outside this expert group understands or appreciates why certain decisions have been made nor the models on which those decisions have been based. What remains is the document graveyard—an archeological evidence of their glorious architectural effort.

Strategy: Marathon or 100 m run?

Today’s businesses face an unprecedented level of uncertainty and fast pace of change in their operating environments. Still, EA in general often favors the grand vision, the long-term-oriented strategy projected several years into the future.

Unfortunately, many EA initiatives tend to inherit the bureaucratic behaviors rooted in typical large enterprises. Therefore, today’s EA, to a large extent, sticks to the work culture of the 1990s and shows many of the traits of a waterfall software development life cycle. This means long review and approval cycles for strategy programs, favoring a strategy that looks forward many years.

Strategy Caricatures

Caricature #5: A Deep Look into the Crystal Ball

Enterprise architectures should not point too far into the future; otherwise they lose touch with reality. After a period of three years, both business situations and technology trends may change dramatically. Any strategy reaching beyond that time period therefore bears the risk of being based on speculation. The EA group may fall victim to tunnel vision, blinding out the creeping deviations of current reality from the projected future.

This situation is often accompanied by the analysis paralysis phenomenon: The enterprise architects are so entrenched in their strategic analysis activities that they do not have time for much else.

All stakeholders outside the EA group will perceive such types of planning as being executed from the ivory tower. This can decrease the appreciation of strategic planning as such—a dangerous path.

Against a backdrop of a volatile and fast-paced business environment, an overly long-term strategy bears many risks. If the milestone for a strategic vision points too far into the future, the impact on the daily business is low. Here the pace of change is painstakingly slow.12 This further widens the chasm between high-flying visions and the IT reality on the ground, often to a point of outright absurdity.

Frequently it does make sense for EA to be “deliberately myopic” about the long-term future. Gartner (2010) recommends that EA have a large portfolio of short-term strategies (around 3 to 12 months) instead of one grand vision. The expectation from the business side is to see incremental progress rather than hoping for a grand novelty far in the future.

Short-term strategies can be planned, executed, monitored, and adjusted incrementally within the context of prevailing dynamics of the external business and technology environment. Even if there still is a long-term vision in place, it is imperative for the enterprise architect to show some short-term benefits. Only that ensures that she can survive long enough to see the fulfillment of the long-term promise. This requires a certain paradigm shift for EA—from strategic to incremental, from meticulously planned to exploratory.

On the other end of the spectrum, very far away from the grand vision, the ultimate hands-on mentality rules. The rush to see quick wins can become so desperate that the enterprise architect ends up addressing tactical issues and plucking only low-hanging fruit. In that case, the EA team ends up not doing any strategic planning at all. Instead, the enterprise architects concentrate only on architecting minor changes to ensure day-to-day operability. Of course, this can no longer be called EA.

Strategy Caricatures

Caricature #6: Sweeping Up the Change Requests13

If the enterprise architect applies too little strategic long-term thinking, the gap analysis between as-is and target states of the architecture is prone to deteriorate into a log of upcoming change requests. Talking to the business users is a very sensible activity for the enterprise architect. However, if she merely records the wish list without abstracting it into a future vision for the IT landscape, she reduces her role to that of a secretary.

Other indications of such a situation is that the EA tool is used as a software change management system and that the future state descriptions read like the solution architecture for the next upcoming software release.

Ultimately, the enterprise architect needs to determine at what point she should concentrate on the strategic intent of the enterprise and when it’s time to turn to the tactical priorities on the ground—in other words, when she is running a marathon and when she’s running a 100-meter run. These are seemingly different races, and the enterprise architect has to find the proper balance in between.

Transformation: Between standstill and continuous revolution

An IT landscape requires continuous evolution. Concentrating only on the operational aspects of IT will not be enough to meet future challenges. Both the innovations on the business side—new products, markets, and business models—and on the technology side, require a constant renewal. It is one of the core tasks of EA to plan and monitor this evolution. The change is either executed in smaller, incremental projects or as large-scale IT transformations. If the pace of change becomes too high, the operability of the whole IT system is at risk.

Transformation Caricatures

Caricature #7: The Permanent Construction Site

If the EA group drives the change in IT at such a pace that all stakeholders gasp for breath, the success of the IT transformations and the proper functioning of IT as a whole are at stake. This situation is often encountered at startups with lots of cash or in enterprises operating in innovative and booming markets.

Here the management is usually technophile and the EA organization dominated by innovation-hungry IT enthusiasts. This mix can lead to a mercurial strategy of radical changes toward the newest technologies without really understanding them in depth. The IT department has no time to develop a mature and consistent technology use; around the corner, the next technology hype is already attracting the focus of IT planners and decision makers.

On the other side of the spectrum, many ambitious IT-enabled business transformation programs come to a complete halt after encountering the harsh realities on the ground. Here is a fictitious example based on a real case. An initiative called Global Spark was undertaken in a manufacturing firm with the following mission statement:

Our strategic initiative Global Spark will deliver a single-instance Order-to-Cash (OTC) platform for worldwide operation that will vastly improve our customer satisfaction and operational efficiency. Thereby it will yield over $215 million in immediate quantifiable benefits and an additional $95 million in year-on-year ongoing benefits.

The intent of the program was to leverage operational synergies among different business units spread across the globe and present a single face of the organization to customers around the world. However, two years down the line, the progress report of the Global Spark program read like this:

Global Spark is being implemented by a leading multinational systems integrator. The development of the technology platform has been under way for two years now. The functional requirements have changed three times, and current requirements are still considered to be in draft state by the major stakeholders. The program was scheduled for completion in an 18-month timeframe but has now been extended to 36 months. It was initially budgeted for $20 million, but we expect costs of $38 million as of now. To date the project has already spent $4 million in requirements gathering, business process analysis, and project planning.

In retrospect, when we look at why so many of these initiatives go wrong, we find that there are many challenges inherent to the complex nature of project management in IT. Quite a lot of these challenges are attributed to the risks involved in new technologies, new processes, and their adoption in mainstream business.

The popular blunders described in the list below are not caused by EA failure. However, a well-functioning EA is able to prevent the worst damage—for instance, by monitoring and timely escalation wherever needed in the following scenarios:

• Pet programs. Often enterprises take up wrong initiatives in the first place. Initiatives are merely shaped without charting a clear strategy or getting buy-in from all the stakeholders. “Pet programs,” usually initiated at the behest of an individual sponsor without a roadmap of their long-term viability, become a problem. By definition, pet programs get a level of attention and investment that is not justified by their value. The problem becomes particularly visible if the sponsor moves on to a different job and her successor does not see the need for the program anymore. Once started, these programs acquire a life of their own and are rarely terminated, even after the sponsor’s exit. Pet programs erode an organization’s bottom line and are a severe drain in terms of costs and resources.

• Poor program management. Another obvious problem is poor project execution. This includes aspects such as inaccurate estimation of the work involved, poor reuse, extensive rework, redundant parallel effort, abrupt project termination, placing projects on the shelf, and production back-out. When inappropriate governance joins hands with poor project execution, the initiative loses momentum. Typically cases of inappropriate governance occur where the sponsors or other stakeholders, rather than the program manager alone, are also accountable for failure. The most common reasons for this situation would be lack of dialogue between business and IT stakeholders, complex cross-organizational engagements, poor accountability, and a major change in business direction partway through the program.

• Over-ambition. This is one of the most frequent causes of failure. It leads to cramping of too many requirements in a single release and, quite often, in the first release. The scope-creep does not leave any ground for priority management or schedule management during the project execution. Furthermore, scheduling too many programs for the available resources eventually leads to a setback in plans. The same applies to scheduling too many programs that focus only on a particular area of the organization, which then is unable to sustain the total pace of change. Every organizational group has only a limited capacity to absorb change. Exceeding that capacity creates a bottleneck and often makes a program fail.

• Technology risks. The risks in new technologies, and the ability of the enterprise to adopt new technologies, can endanger success. The immaturity of a technology platform or the inadequacy of a technology for the problem at hand are often overlooked under the pressure of releasing a solution in time. Technologies are volatile; they evolve continuously, or even worse, they come and go. Consequently technology platforms change in rapid succession. Although technology providers tend to ensure that their platforms have a support life of at least five years, in reality this is much less due to the lead times and delays within the enterprise while migrating to the newest version.

Transformation Caricatures

Caricature #8: The Ever-Growing Backlog

An EA organization that neglects change programs in the IT landscape—whether for lack of budget, planning capacity, strategic direction, or other reasons—just piles up a debt of necessary changes and adaptions.

If the enterprise architect is not driving change in the IT landscape but merely documenting it, he turns into a chief librarian rather than an architect of the IT landscape. The EA organization deteriorates into a documentation graveyard. The probability is low that someone will ever do anything useful with models and documents just stockpiled without an explicit purpose. And if these documents and models are indeed revisited at some point, chances are that they will be hopelessly outdated by then.

Of course, despite all risks in IT transformations, avoiding them altogether (as sketched in the caricature The Ever-Growing Backlog) just piles up a debt of necessary changes and adaptions. Reducing the system changes to only the most needed maintenance activities is only advisable for low-value-contributing support systems, which are run in the most cost-efficient way. Ultimately, change will always be required in some form or the other. Therefore, a well-working EA function is needed to deal with it.

Enriching EA by Lean, Agile, and Enterprise 2.0 Practices

“Action speaks louder than words but not nearly as often.”

—Mark Twain

After this analysis of EA shortcomings, let’s look forward again. We do not want to appear like a bunch of notorious bickerers: We also came across many enterprises in which a neat EA practice indeed showed its benefits. But there always was wide room for improvement, and tendencies to the one or other caricature described in the previous sections were always perceptible.

Our analysis of EA failures and shortcomings has revealed that EA needs to find its proper position in a complex and chaotic environment. The solution is not about eliminating chaos altogether. That would overstretch the meager powers of the EA or IT organization, or it could turn EA into an overly rigid control freak—just the other side of the coin.

As we will see, the real issue is to balance chaos and order properly. The question is how to leverage chaos to increase orderliness. “Chaos is created by people trying to solve immediate business problems, [and] you need to harness that energy even if it creates systems chaos,” writes Eckerson (2011). The answer is given by a concept called the Edge of Chaos, originally introduced by Kauffman (1995) and Brown and Eisenhardt (1998). In brief, this concept states that any dynamic system works most effectively when order and chaos are in balance. Both too much order and too much chaos are counterproductive. We have incorporated the Edge of Chaos into an EA Dashboard that measures this order-chaos balance.

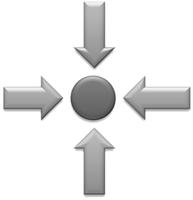

The EA Dashboard, as depicted in Figure 1-2,14 is a yardstick to measure any improvement proposals for EA. It is based on the dimensions of EA complexity introduced in the previous sections. We will introduce the classification criteria in detail in Chapter 6. As a general rule, based on our analysis of the EA failures in the previous section, it makes sense to seek a middle ground between the extremes on each gauge. We will measure the potency of our proposed EA improvements against this Dashboard.

Figure 1-2 The EA Dashboard as a yardstick for effective EA.

But how can we achieve balancing EA between the extremes on the EA Dashboard? We do not believe we have the panacea for all grievances about EA. Nevertheless, something must be done to prevent EA from slipping into the gray mediocrity of yet another IT function that doesn’t make an essential difference. This is basically what this book is about: proposals to take action. There is a lot to be done.