Chapter 3

What Enterprise Architects Do

Core Activities of EA

Content

Defining the IT Strategy (EA-1)

The Role of an Enterprise Architect

Modeling the Architectures (EA-2)

Models and Views of Various Architectures

Visualizing Cross-Relations and Transformations

Evolving the IT Landscape (EA-3)

Assessing and Building Capabilities (EA-4)

Competence Development for Enterprise Architects

Formalizing Enterprise Architecture

EA Team Position in the Organization Structure

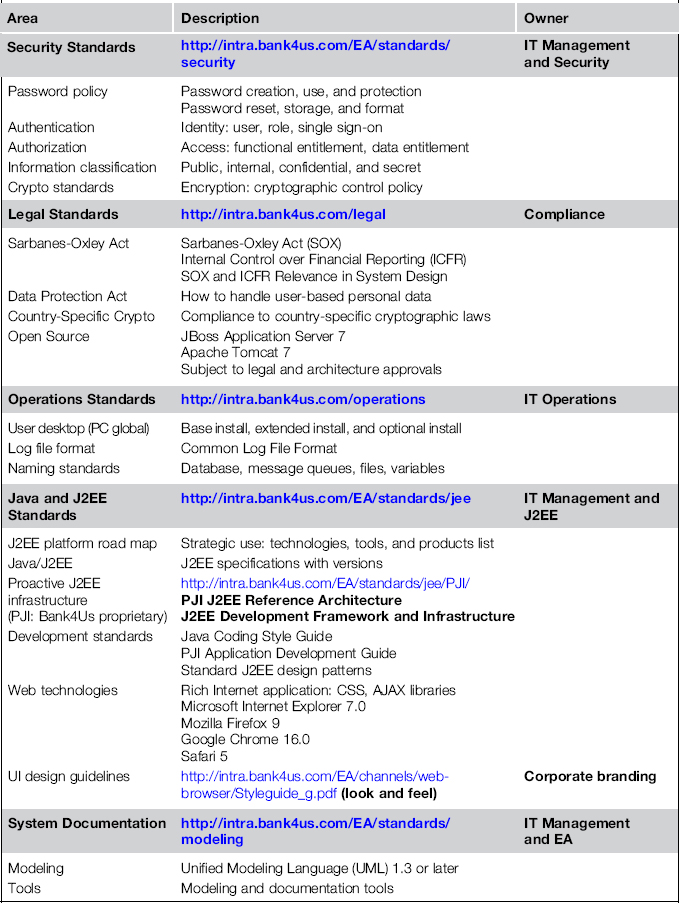

Developing and Enforcing Standards and Guidelines (EA-5)

Standardizing on Technology Usage

Enforcing Standards and Guidelines

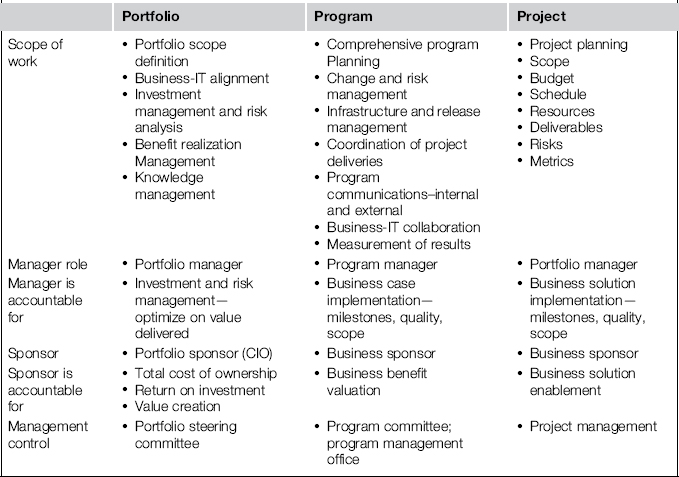

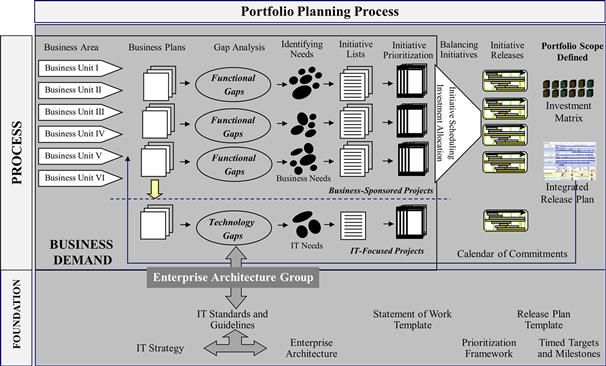

Monitoring the Project Portfolio (EA-6)

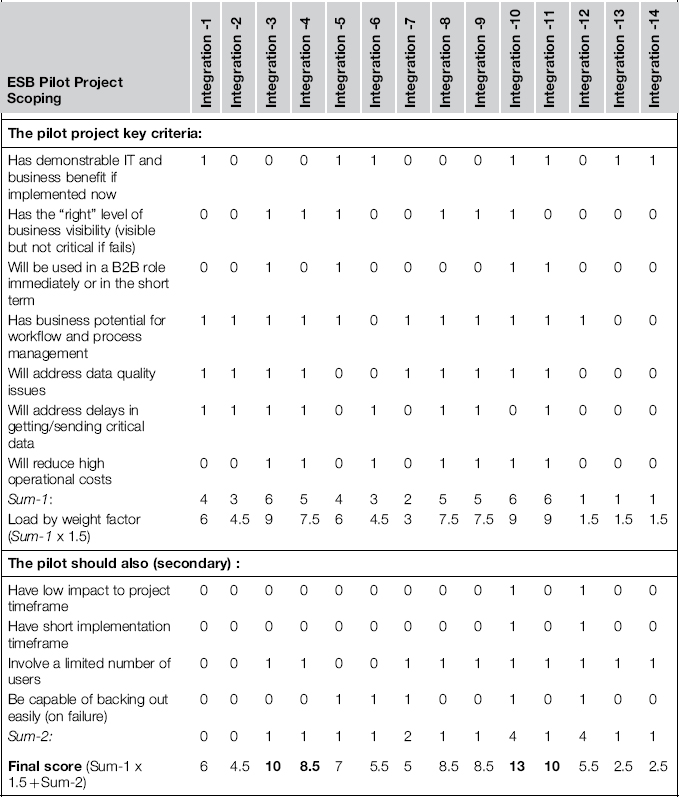

Building the Project Portfolio

In this chapter, we dig deeper into the question of what enterprise architects actually do to manage an enterprise’s architecture. What duties belong to their role and make up their profession? What kinds of activities characterize their daily work, and what are the established best practices to perform those duties?

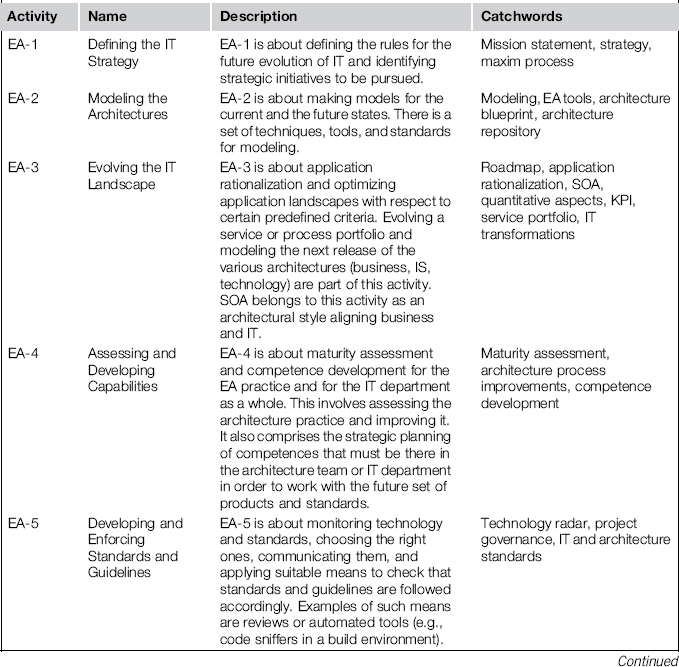

Because of the many facets of EA, any compilation of EA activities will probably be incomplete, but the selection we lay out in this chapter lists the situations we most frequently encounter in both practice and literature. The activities we find most characteristic and prevalent are shown in Table 3-1.

Table 3-1 Core Activities of Enterprise Architecture Management

The emphasis on activities can be different in each firm; an activity that gets the most attention in one firm might be almost neglected in another. Therefore, we do not make an attempt to prioritize activities by importance or effort involved. Neither are we interested in putting them into a sequential order; this is achieved by frameworks such as the TOGAFTM Architecture Development Method, which we’ll take a look at in the next chapter.

Instead, the two major goals here are drawing a realistic picture of the kind of work that enterprise architects are entangled in and describing some of the established practices to succeed. But we’ll constrain ourselves here to contemporary best practices, meaning approaches you can find out there in the field or in the relevant publications. They’re not our invention, and in the following sections we describe those practices that are, in our own judgment, most well known and convincing.

In contrast, Part II of the book (Chapters 6 through 8) is dedicated to improvements of the state of the art. We will frequently refer to EA-1 to EA-8 (as shown in Table 3-1) to assess in which activities the improvements can do some good and how they change the current way of working.

But for now we’ll stick to the current practice and hope that the newcomer to the subject gets a tangible view of EA, whereas the old hands may enjoy a quick recap, hopefully learning about one or two items they didn’t know about before.

Defining the IT strategy (EA-1)

Half of the activities of EA are strategic by nature. Evolving the IT landscape, for example, entails drawing the future information system landscape, which certainly gives a strategic direction. But EA-1, as we shall see, sets up the principles guiding all subsequent strategic decisions and thus is the root and point of departure for strategy.

Defining the IT strategy positions IT in the enterprise environment and future direction and defines how IT can be better utilized to attain business goals. This process consists of three steps:

1. Defining the goals to be pursued over the time span covered by the strategy

2. Stipulating the rules that dictate how these goals are to be reached

3. Identifying the initiatives that move the enterprise’s IT toward the goals

In this section, we’ll walk through these steps one by one and explain the challenges and approaches involved in each of them.

Defining the goals

Let’s first take a look at an example of a typical business goal: The automotive industry has become highly volatile in the past few years. Manufacturing plants are shooting up like mushrooms in emerging markets, and the car companies force their suppliers to keep up with this rapid pace. As a manufacturer of shock absorbers, for instance, you must be able to build up a new supply plant sufficiently fast wherever in the world your major customer decides to build cars; otherwise, you’re out. The ambitious goal your business management derives from this challenge is:

We must be able to ramp up a plant in half a year in any geographic region, and we want to reach this capability in one year.

This is a business goal, and quite a good one. It scores quite high when benchmarked against the acronym SMART. This quality seal gathers the features a useful goal should have: Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Relevant, and Time-bound. The previously stated business goal could be a trifle more specific about the geographic regions and under what conditions a plant is considered “ramped up.” But it at least states a metric and the ramp-up time and nails down the time horizon of one year (it is time-bound). The addressees probably recognize it as relevant and roughly know the first steps to act on it (it is actionable).

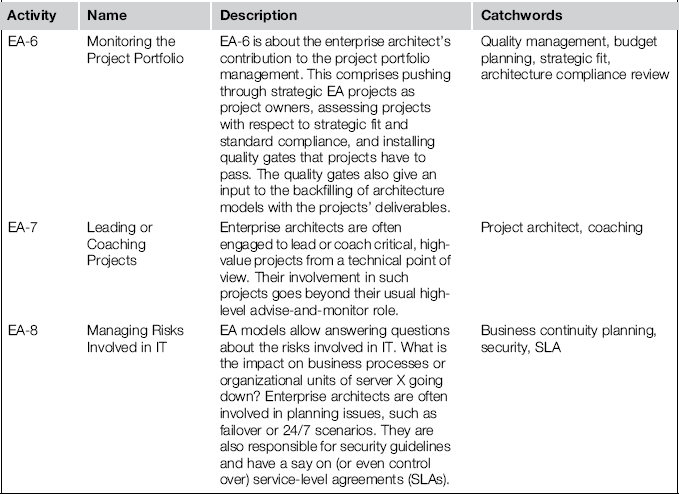

But in practice, one often finds that goals lack some or all of the SMART qualities. Mack and Frey (2002) list some caricatures of goals that are, for instance, absurdly unspecific: “Increase our market share,” “Make our products more attractive,” “Keep existing customers and acquire new ones.” It indeed is close to impossible to derive guidance from such goals—in particular if they just are a small excerpt of a long CEO Christmas list. Platitudes like this don’t pass the “Dilbert Test” illustrated in Figure 3-1: State the opposite, and watch whether something absurd takes form.

Figure 3-1 The “Dilbert Test” for platitude goals.

The Christmas list, meaning the obstacle of an unfocused or even contradictory set of goals, can only be mitigated by urging the board of business managers to decide for a handful of them. If the business leaders decide to drop “Make our products more attractive” but not “Keep existing customers and acquire new ones,” we at least have a clue where the business is heading. Strategic initiatives consequentially should invest in marketing and CRM rather than in improving the product development or manufacturing chain. In most cases, however, the issue won’t be an “either/or.” Instead, prioritization of goals will be required, a step that inherently belongs to defining goals. A choice or ranking implies a mandate to act on, and the maxim process we shall describe a little later can help in pushing a business board to make it.

Several flavors of the term goal are in use. Some talk about objectives, some about requirements, and others swear by formulating visions. These flavors have their point, but in terms of the bottom line it is all about agreeing on what is wanted, how eagerly it is wanted, and maybe who wants it. There’s no need to be overly subtle about it.

Stipulating the rules

There’s a broad consensus that defining the IT strategy is an exercise that cannot be achieved without an intense collaboration between business and IT. Broadbent and Kitzis (2005) regard the involvement of senior business executives in the definition of the IT strategy as the crucial factor in turning IT from a cost-generating infrastructure to a business enabler. Nevertheless, in practice it is difficult to get business executives on board.

A proven approach to tackling this obstacle is the so-called management by maxims process conceptualized by Broadbent and Weill (1997). The process is far from being rocket science: It boils down to gathering the senior business and IT representatives for an intense one-day brainstorming workshop. The pain of business executives to devote some time to IT is thereby kept at a minimum. To make the most of such a day, there must be three topics on the agenda:

• Definition of the business maxims

• Derivation of IT maxims out of the business maxims

• Agreement on the extent of shared services and infrastructure support

For the day to be a success, the topics must previously be prepared by some assistants; the enterprise architects typically belong to this group. On the day itself, it might be just the chief enterprise architect who is invited to the illustrious workshop.

The first two agenda items are about maxims. Broadbent and Kitzis (2005) define a maxim as a “statement that specifies a practical course of conduct.” They recommend formulating not more than six business maxims that “[…] need to be concise, compelling, concrete, easily communicated, and readily understood as statements that people throughout the entire organization can use as guidelines for making decisions and taking actions.” Here are two examples of good business maxims taken from their book (2005, pp. 84, 91):

• All sales employees are decision makers about taking new policies and cross-selling.

• Maximize independence in local operations with a minimum of mandates.

Deducing IT maxims from such business maxims is the second topic on the agenda. There can be more IT maxims than business maxims, but the catalogue should still be crisp enough to be remembered by members of the organization in their daily decisions. The two examples stated previously, for example, could give rise to the following IT maxims:

• All sales employees, wherever they are, must have access to contract and customer data.

• Business units can determine the most suitable applications for their business, provided they comply with a minimum set of standards set throughout the enterprise.

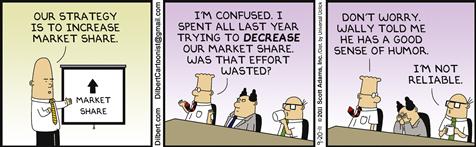

The last item on the agenda is to get an idea of the enterprise’s need for shared services and infrastructure. The deeper rationale for this exercise is to position the firm (or maybe even individual business units) in what Jeanne W. Ross from the MIT Center for Information System Research calls an operating model. Ross (2005) distinguishes four main categories of operating models, as shown in Figure 3-2.

Figure 3-2 Four operating models (Ross, 2005, used with kind permission)

Technical people, especially technology-focused architects, have a bias for standardization and integration and tend to believe that these most naturally belong to the canonical goals of each enterprise. But it is not a matter of maturity in which of the quadrants of the Ross model an enterprise ends up; it depends on the business outlook, the competitive strategy, and the enterprise governance. Let’s take a brief look at each of these parameters.

Broadbent and Kitzis (2005) distinguish three fundamental business outlooks, namely:

• Fighting for survival. Budget cuts, layoffs, and cancellation of initiatives characterize this outlook. The emphasis is on cost reduction.

• Maintaining competitiveness. The enterprise is parsimoniously balanced between cost savings and investments in initiatives. Budgets are flat, and new initiatives must be thoroughly justified.

• Breaking away. These are the happy days for new initiatives. Budgets are generous, and the challenge for IT is in keeping up with the growth, or even better, driving it.

The second parameter following the business outlook that influences the need for standardization and integration is the competitive strategy. The economist Michael Porter (1998) describes three generic strategies that, on a rough scale, classify all approaches to competition. These are:

• Cost efficiency. Offering a better price is the main competitive advantage. The emphasis is on operational excellence to keep costs low.

• Differentiation. The enterprise tries to combat competitors by better products, quality, or customer care. The emphasis is on product leadership or customer intimacy.

• Focus strategies. The enterprise gains advantages from occupying market niches.

Even in the generic terms sketched here, it becomes evident that an enterprise architect who is much in favor of standardization and integration can do harm to an enterprise that is breaking away and strives for differentiation by developing the most innovative products on the market. While business is demanding a rapid positioning of new IT applications and services, the EA hits the breaks by imposing standardization and integration compliancy on the development teams.

Enterprise governance is of equal importance as the previous two parameters. Weill and Ross (2004) define governance as a body of meta-regulations for management, stipulating the following issues:

One core question decided by governance is how much autonomy is granted to business units or geographical regions. In case this autonomy is high, would a quest for high IT integration and standardization not be like fighting windmills?

Therefore, the enterprise architect must be aware of the business outlook, the competitive strategy, and the enterprise governance and must use them as landmarks in decision making. The maxim process provides a useful opportunity to call for information about these parameters.

A remarkable feature of the maxim process is that it is about abstract rules only. Broadbent and Weill (1997) coined the term management by maxims for a kind of strategy definition founded on abstract decision rules. This approach actually does away with a popular misunderstanding of what a strategy actually is. Elementary game theory defines a player’s strategy as a “complete plan of action for whatever situation might arise; a plan that fully determines the player’s behavior at any stage of the game, for every possible history of play up to that stage” (Wikipedia “Strategy,” 2011). The player becomes an executor of an algorithm in this conception, as visualized in Figure 3-3.

Figure 3-3 Strategy as algorithm: A popular misconception.

But for complex games like chess, there is no algorithmic strategy that guarantees a win. Who would expect that there is an algorithmic plan of action that guarantees a successful transformation of the enterprise’s IT, a plan ensuring that all business goals are met? This algorithmic concept of a strategy has its limitations.

Complex systems cannot be managed at an object level, only at a meta level. This will be one of our insights we discuss in Chapter 6, “Foundation of Collaborative EA,” where we reflect on the key implications of complexity. Management at a meta level basically means management by maxims.

Existing frameworks for defining an IT strategy widely acknowledge this constraint. The TOGAF framework, for example, uses the term principle instead of maxim. But principles are defined as “general rules and guidelines […] that inform and support the way in which an organization sets about fulfilling its mission” (The Open Group, 2009, p. 265). Thus, principle can in practice be regarded as a synonym for maxim. Principles are identified in the Preliminary and Architecture Vision phases of the TOGAFTM ADM, and they form a foundation for the subsequent architecture definition endeavor.

It is a good practice to accompany the bare statement of a principle by a rationale, a set of implications the principle might have, and possibly further auxiliaries such as metrics or the application context. This helps the decider and is recommended by TOGAF as well as by Weill and Ross (2004).

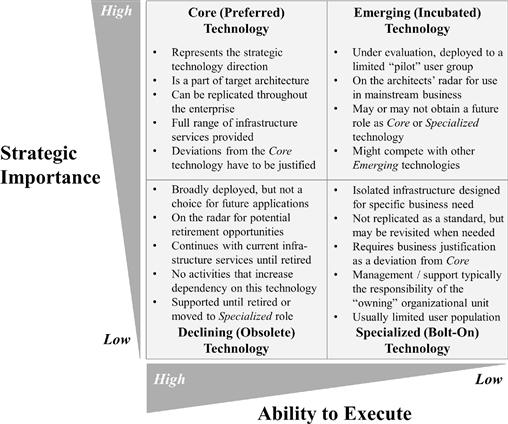

The Gartner Grid

Gartner Research has elaborated another methodology for formulating IT strategies in a series of papers published during the years 2002 and 2003. The definition of strategy in these papers is very concise (Mack and Frey, 2002):

A strategy takes a vision or objective and bounds the options for attaining it.

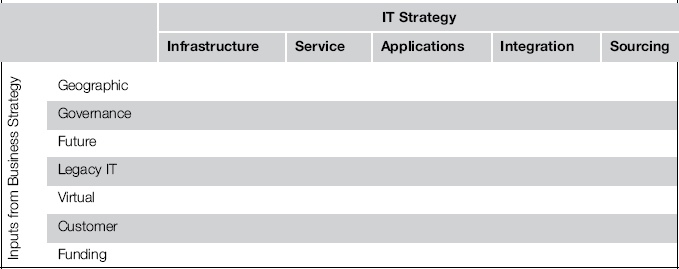

The approach to “bounding the options” actually is spelling out abstract decision rules and therefore is yet another instance of management by maxims. The most often cited concept from Gartner’s papers is the two-dimensional grid shown in Table 3-2. This grid can be used to check the completeness of IT strategies.

Table 3-2 Business Strategy Elements Mapped to IT Strategy

On one hand, this grid ensures that all aspects of the IT strategy that may require a decision further down the road are guided by rules. On the other, it lists all inputs from the business strategy that can have an impact on IT and therefore must not be neglected.

The seven inputs from the business strategy are spelled out as follows:

• Geographic. This is about the expansion and national/international distribution of the enterprise.

• Governance. Who makes decisions, and how are they made? Are the business units or geographic regions relatively autonomous, or is there a strong central authority?

• Future. This concerns how far the time horizon of business plans is. They can be long-term, midterm, or even bound only to what has to be done next.

• Legacy IT. Is there a will to make drastic changes, or is the attitude conservative and committed to the current way of operation?

• Virtual. This is about the involvement and integration of service providers and other partners. What capabilities and processes are kept in-house, and which are handed over to partners?

• Customer. How strongly does the enterprise want to engage its customers?

• Funding. Who is paying and how much? How are projects funded, and what are the criteria for granting budgets?

These inputs must be taken into account, according to Gartner. If they are not available right away, the enterprise architect must seek answers and hold the business side accountable for giving them.

The business imperatives are then mapped to five components of the IT strategy, which can briefly be explained as follows:

• Infrastructure. This is the technology component, comprised of hardware, software, and network elements.

• Service. This concerns the services provided by the IT department to the enterprise, to partners, and to customers.

• Applications. This is about the portfolio of applications, their business functions, and the processes and organizations it supports.

• Integration. All means making the enterprise act as a single unit are subsumed under this component.

• Sourcing. This component addresses the source of all the people who perform the IT-related strategic work. In particular it sets rules for selecting internal employees or external service providers.

Now, how can we use the Gartner grid in practice? Let’s take the example of an automotive supplier and the goal we discussed earlier:

We must be able to ramp up a plant in half a year in any geographic region, and we want to reach this capability in one year.

This requirement can be seen as one of the inputs in Gartner’s Geographic row. But what does it imply for the different columns of the IT strategy? Here is a walk-through that should sketch the idea:

• Infrastructure. The IT organization decides to go for highly standardized technology stacks that can rapidly be replicated to new sites. The rule is to prefer out-of-the-box solutions over custom implementations.

• Service. The guideline is to rely as much as possible on onsite services but to work according to the standards established in other parts of the world. Services are to be provided in the local language.

• Applications. The principle is to utilize the standard applications and global templates of business processes. Customization must be justified by strong reasons—for instance, country-specific legal constraints.

• Integration. The integration is to be kept to a minimum. Integration costs grow over-proportionally with the number of sites, and a tight integration can slow the implementation.

• Sourcing. The work is done by onsite forces. External suppliers are preferred in order to keep latencies for training and education at a minimum.

In practice, the mapping rarely is straightforward and without logical conflicts. A good governance of strategic planning should not leave the IT side alone with business requirements that are impossible to accomplish. Instead, there must be feedback loops allowing for a reconsideration or reprioritization of business maxims.

Identifying the initiatives

Just envisioning the goals and stating the rules does not get things going. One also has to identify the strategic initiatives people should start working on. We intentionally use the term initiative because the plan of action is usually yet too coarse to speak of well-scoped projects. At this granularity, it is not about a proper project portfolio management: The how is widely unclear, there’s no target architecture in place, and all we have is intentions to start with. A typical scenario would be an imaginary car manufacturer, Cars4Us, which has committed to the goal of keeping existing customers.1 A high-level business maxim aiming at this goal could be:

We make the customer perceive us as a helpful companion, and we maximize the number of services and contact points accordingly.

The different business units of Cars4Us examine this maxim and come up with initiatives as to how to put this into practice. Customer care concludes they should point the customer to all service incidents and technical checkups in advance. Therefore, they take up a business initiative that models the whole life cycle of a car, with all probable events and corresponding interactions (car care, repairs, new purchase, etc.) with the customer. The IT initiative derived from it implements this process in the customer relationship management (CRM) system and automates such things as sending notification mailings about upcoming technical checkups.

Marketing, on the other hand, intends to extend the services beyond the narrow scope of car caretaking. They kick off an IT initiative centered on mobile applications in order to explore what kind of helpful gadgets could be offered on a smartphone. The range is wide: racing games with Cars4Us models, augmented reality manuals for the car, or apps alerting the user to events such as concerts or football games close by. The initiative is complemented by an investment into customer analytics. Cars4Us wants to learn about the customer and her wishes from the mobile interactions.

This example illustrates that there’s no way to systematically deduce the right initiatives. There’s not even a framework for guidance. One is left to one’s own creativity and a thorough understanding of the enterprise and the way the business is run.

The initiatives usually do not directly lead to implementation projects. The latter are rather pursued by pre-projects detailing the requirements and target architecture to a level that allows for proper project planning of effort, business value, and risks involved.

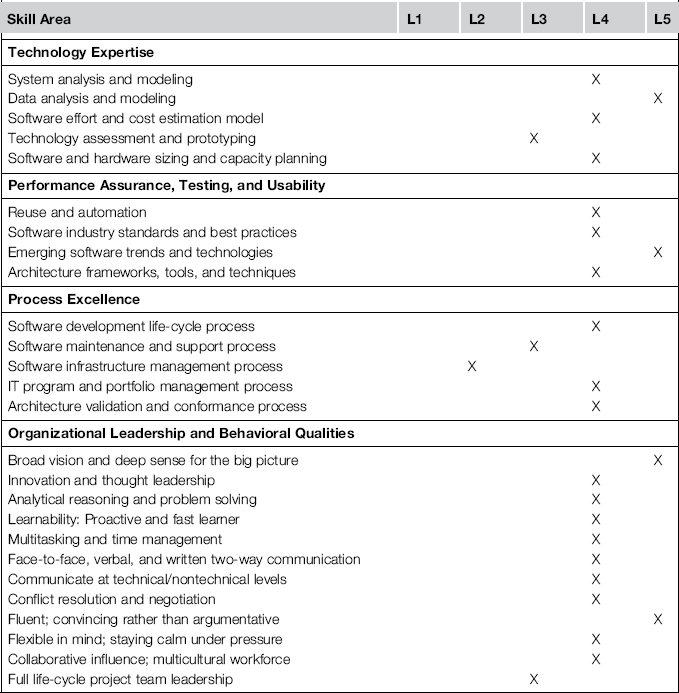

The role of an enterprise architect

Enterprise architects are typically not accountable for the enterprise’s IT strategy. It is the CIO who signs off on it and has to answer for it. Nevertheless, enterprise architects usually participate in strategic boards and meetings, prepare decisions, or elaborate drafts coming out of such meetings. There can be parts of the IT strategy on which enterprise architects have little to say—for instance, in defining service-desk policies. But even if they are not primary speakers in these parts, they are at least informed or consulted. Hence EA is deeply involved in shaping the enterprise’s IT strategy.

Defining the IT strategy is a hot spot with regard to interpersonal issues, since it is on the borderline between business and IT and critically depends on the collaboration between the two. In a sense it is the stage for a culture clash, a meeting point of businesspeople on one side and IT folks with roots in programming on the other. On university campuses these two species looked at each other with suspicion, sometimes even with deprecation. If the atmosphere between business and IT is poisoned anyway, which is not a rare constellation, it is embarrassing how such meetings can easily distort into recriminations. The enterprise architect sits on the borderline between these two camps, and the best thing for him to do is to take on the role of moderator. This requires a good dose of political aplomb.

Modeling the architectures (EA-2)

Models and views of various architectures

Making architecture models probably is what most people primarily associate with the profession of an architect. Software developers expect the architect to come along with a blueprint for implementation. Managers expect they have to gaze at annoyingly complex diagrams when an enterprise architect starts explaining why a cable fire affected so many business processes.

Models are abstractions of some part of reality. They suppress irrelevant details but strive for being accurate with respect to the points of interests. Models are always bound to a certain purpose; otherwise there is no way to tell what is relevant and what is not. An enterprise architect, for instance, models the way IT is currently used in the enterprise as well as the roadmap to future use. But she typically does not model the air conditioning in the server rooms or the cabling for employee workplaces. What goes into the model and what is left out depends on the model’s use cases, and there is a wide range of things that can be done with an enterprise architecture model, namely:

• Design and planning. The model is a tool for designing the future evolution of the enterprise’s IT. It is a means to identify the gaps between as is and to be and the corresponding needs for action.

• Analysis and assessment. The model helps analyze the impact of incidents or changes. It allows assessing issues such as strategic fit, compliance with laws and regulations, or risks.

• Implementation and operation. The model is a framework of orientation for detailed design. It is a knowledge base for operating and maintaining information systems.

• Communication and enforcement. The model is a foundation for explaining and motivating changes. It is a means to assure that the intended architecture is actually implemented in the intended way.

There are probably more use cases than the ones we’ve listed, but this selection suffices to characterize the model as an important asset of enterprise architecture management. On the other hand, making and maintaining a model is laborious and expensive. Therefore, one should not ride a hobbyhorse when doing so but instead stick to what the actual use cases require. Striving for completeness, true-to-detail reproduction of reality, compliance to some architecture standard as an end in itself, or gold-plating the model is a waste of effort.

Communication is a use case deserving special attention. The enterprise architect uses the model to answer specific questions of stakeholders. Take, for example, the country head of an enterprise’s Mexican branch. He wants to learn about a new global business process that is planned to replace a local mode of operation. Concerns like this are not directly addressed by the model itself, and the enterprise architect is well advised not to present raw model material such as business process modeling notation (BPMN) diagrams to senior managers. Stakeholders have a specific viewpoint on a subject, and their perspective must be addressed by a corresponding view on the model.

The country head, in our example, wants to know whether the business process replacement changes the roles and responsibilities of his personnel, whether there are any investments needed, and how the IT total cost of ownership is affected. Other aspects such as strategic fit with the global IT strategy are of little interest to him. It is the enterprise architect’s job to draw a tangible view, custom-tailored for this specific stakeholder.

The distinction between model and view is sensible and commonly made.2 There actually are technically oriented people who believe that the model is the sheer truth, whereas views are what you “tell the kids.” But the enterprise architect who seriously takes the role of mediator between the various parties who have stakes in IT should abandon this somewhat nerdish attitude.

A holistic view of the enterprise’s IT requires more than one architecture to cover all aspects. On the business side, we have the business architecture that is concerned about the business goals, key performance indicators, organizational units, geographical locations, processes, business capabilities, and even more entities of the business realm. On the technology side there is the infrastructure architecture, consisting of servers, networks, data stores, software products, standards, frameworks, and further miscellaneous hardware and software thingies of which a runtime environment is composed. The TOGAF framework we are going to take a closer look at in Chapter 4, “EA Frameworks,” distinguishes as many as four different architectures that are layered from the business architecture down to the technology components: business architecture, data architecture, application architecture, and technology architecture.

Visualizing cross-relations and transformations

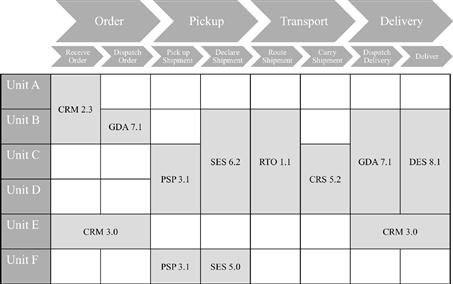

Enterprise architects are in charge of making the entanglement of business and IT comprehensible. The models they create must therefore capture relations between all architecture layers, from business down to technology. Likewise, the views on top of these models should visualize how the entities of the layers, which in a first approach appear rather isolated, are in fact interwoven. Figure 3-4 depicts a highly simplified but typical example from a fictitious logistics company.

Figure 3-4 Process map.

This process map draws a relationship among business processes, the organizational units in charge of them, and the applications supporting these units in their duties. It highlights, for example, that the organizational Unit B uses a rather old 2.3 release of the CRM system, whereas Unit E is already equipped with the more modern release 3.0. As a consequence, Unit B has to work with the legacy applications GDA and DES to manage the whole pickup and delivery processes.

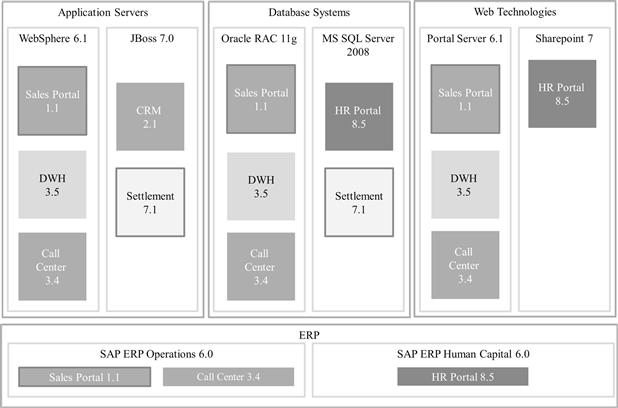

Another kind of view that is widely used to visualize relations is the cluster diagram. Figure 3-5 is, again, a highly simplified example of a more technically oriented cluster diagram that draws a relationship between technology platforms and applications based on those platforms. The applications are sorted into clusters according to the technology they are built on; the reader can learn from it, for example, that release 7.1 of the Settlement application is built on an exceptional technology mix (MS SQL Server and JBoss) that might not accord with an enterprise’s technology standards.

Figure 3-5 Cluster diagram.

We can choose from among a large variety of process maps and cluster diagrams. The process map can, for instance, also be used to visualize relationships between processes, supporting application functions, and business objects involved in these functions. But the two examples shown should suffice to illustrate how they address relationships, dependencies, and cross-concerns. The reader interested in a broader treatment of best-practice EA views may refer, for instance, to Hanschke (2010).

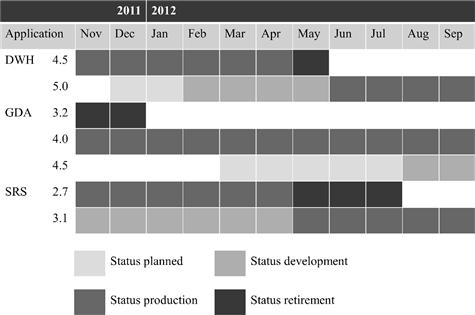

Another peculiarity of enterprise architecture models is that they have a time dimension. The models do not merely present a snapshot of the architecture(s) at a particular point in time; they capture the current state, the future desired state, and possibly a roadmap of transition states along the way. Figure 3-6 is a simplified example of an application roadmap addressing the evolution of the application landscape.

Figure 3-6 Application roadmap.

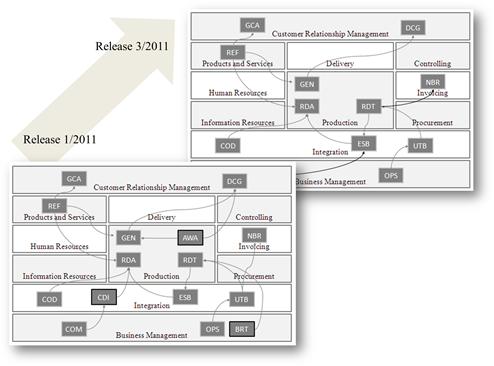

Another frequently used means of eliciting “Aha!” effects of how things will evolve is a flip-book of consecutive states, like the one in Figure 3-7. The two consecutive states show the simplified application landscape of a logistics company, clustered by functional domains. The arrows mark the data flow with regard to a central business object. The flip-book now clearly demonstrates the effect of an application rationalization on this flow.

Figure 3-7 Flip-book visualization of an application rationalization.

There is an abundance of variants of such landscape maps. You may use them to relate applications with technology stacks, business objects with application functions, or whatever results in a better understanding of how the bits and pieces fit together.

Modeling standards

The notation, terminology, and conceptual meta-model of enterprise architecture models are not standardized in practice. Unlike software design, where most practitioners nowadays agree that the Unified Modeling Language (UML) is the language in which to express software architectures, there is no such convention about enterprise architecture. Some core concepts such as business process can be found in most models; even there the notation and maybe also the definition are not unanimous among enterprises. The modeling language being used in an enterprise is formed by the vocabulary of concepts that has grown over the years, condensing much of the organization’s view of the world as well as the vendor-dependent taxonomy of the modeling tools that are in place.

The nonexistence of a universally understood, reliable language to communicate about enterprise architecture has become an obstacle—even more so in a business context that increasingly counts on collaboration between people and joint ventures of partners. ArchiMate is a modeling standard that is supposed to overcome this obstacle and that up to now remains the only serious attempt to standardize EA notations.

ArchiMate was designed by research institutes and universities in the Netherlands from 2002 to 2004. Since 2008 it has been under the stewardship of and published at The Open Group (2008). As we shall see in the description of the TOGAF framework in Chapter 4, the taxonomy of ArchiMate resembles TOGAF’s own content meta-model. ArchiMate therefore is a perfect fit for modeling the architecture layers along the phases of the TOGAF Architecture Development Method.

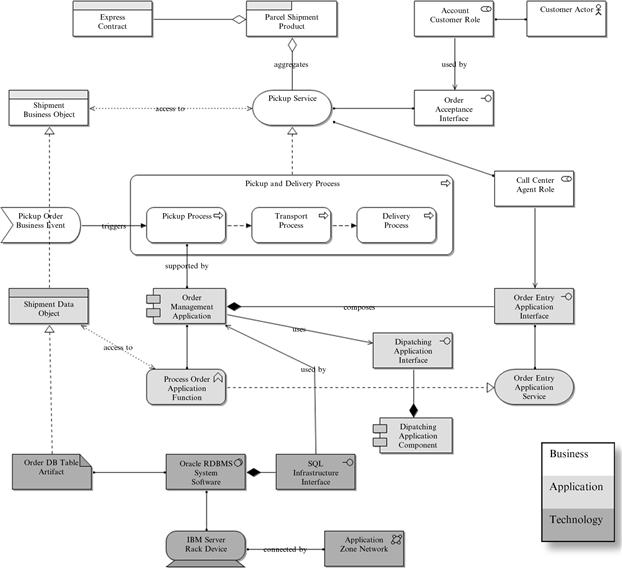

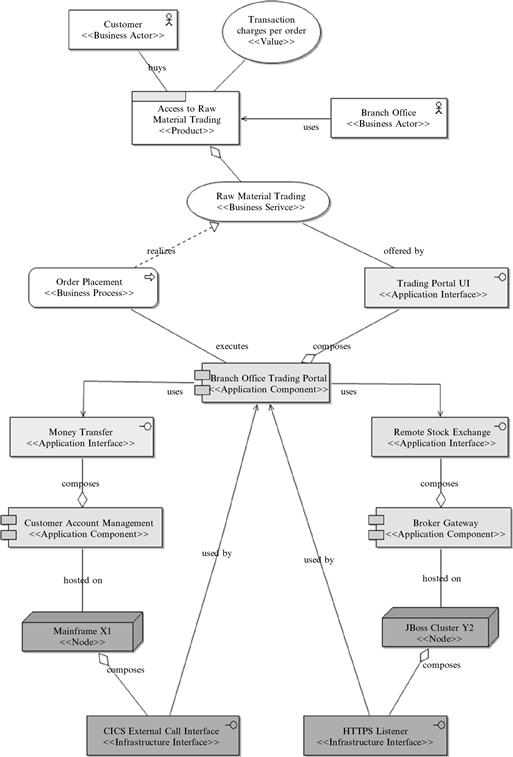

Figure 3-8 shows an example of how ArchiMate models a simplified pickup and delivery process that belongs to the core express business of any logistics company: Customers can ring up a call center and request the pickup of a parcel from some place in order to get it transported to a destination address.

Figure 3-8 ArchiMate model example.

The standard distinguishes three modeling layers—namely the business, application, and technology layers; they are depicted by different shadings in Figure 3-8. Let’s briefly traverse these layers from top to bottom to get to know the most important concepts of the ArchiMate taxonomy.

First we learn from the business layer that the pickup and delivery process consists of three subprocesses: pickup, transport, and delivery. Furthermore, the process implements the pickup service, a business service offered to customers as a part of the parcel shipment product governed by an express contract. The service is supported by call center agents and used via the order acceptance business interface by customers that have registered accounts. The process is triggered when a customer calls up the pickup service and thereby issues a pickup order business event. The customer submits information such as the consignee address, which is comprised in a new shipment business object.

The next layer, application, tells us that the pickup subprocess is supported by the order management application. The application offers a process order application function that is used by the call center agents via the order entry API, the user interface of the application. Furthermore, the order management application invokes an API of the dispatching application to assign orders to pickup routes.

The bottom layer eventually shows how infrastructure components such as database systems, servers, and network segments host the order management application.

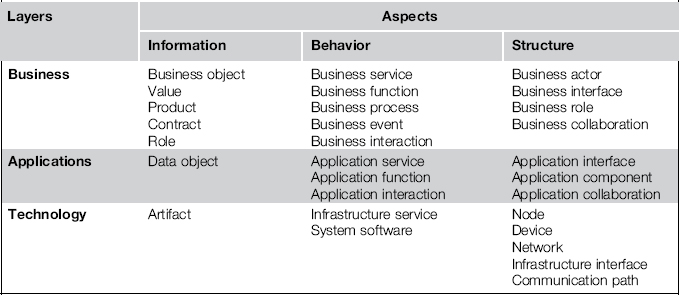

Though rather simplified, the example conveys an impression of how ArchiMate models entities, in particular of the granularity of detail it addresses. The decomposition of the process, for instance, is much coarser than the detailed flow modeled by a BPMN3 diagram. The modeling of applications does not go deeper than the delineation of applications and their functions and interfaces, which is much less than what is usually captured in a UML model. This granularity is quite suitable for modeling larger parts of an enterprise IT-landscape, and the ArchiMate vocabulary, which is summed up in Table 3-3,4 indeed offers the concepts needed to do so. Furthermore, the standard also addresses the requisite cross-relations from business down to technology, which is a major concern of EA modeling.

Table 3-3 The ArchiMate Taxonomy

But ArchiMate also has some shortcomings.5 The concepts are ambiguous and not as straightforward to apply as intended. In practical work, you often start wondering whether, for instance, this portal page now offers a business service, a business function, or an application interface.

When it comes to communication, models like Figure 3-7 also tend to be a trifle bulky; such drawings must be interpreted and simplified by views to convey a message to stakeholders. ArchiMate proposes some standard views that leave out model elements or use simplified relationships to come to drawings that are simpler to grasp. (For more details, refer to the chapter “Architecture Viewpoints” in The Open Group [2008].) But in practice the architect needs to expend some creativity to create additional views in PowerPoint so she can get her ideas across.

Although ArchiMate is not that old as a standard, there are already remarkably many EA tool vendors claiming support of the standard—for example, Rational System Architect by IBM, BizzdesignArchitect by Bizzdesign, or Abacus by Avolution. There is also an Eclipse-based open source tool for drawing ArchiMate models, called Archi6; maintained by the University of Bolton (UK), it accurately implements the standard and works well in practical use.

But managing the enterprise architecture with Archi, Microsoft Visio, or any other plain drawing tool is an impossible undertaking. The costs of keeping the data up to date are prohibitive, and the rift between model and reality will soon be insurmountable. Such drawing tools fall short of the major requirements an EA toolset should fulfill beyond capturing plain models, namely:

1. The tool has a timeline for planning and simulating future states of the architectures.

2. It supports quantitative assessments and optimizations of the IT landscape; in other words, it supports application rationalization.

3. It has rich facilities to visualize models and craft views addressing specific stakeholder viewpoints as well as publishing functions for sharing knowledge.

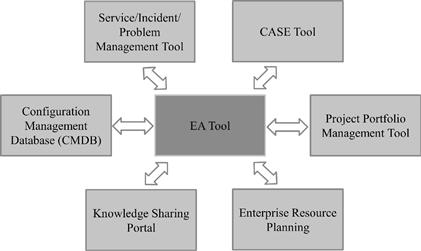

4. It is integrated with other tools, as depicted in Figure 3-9.

Figure 3-9 An EA dream: The integrated EA tool.

5. It facilitates communication by feedback, collaborative authoring, and other means of participation.

Dedicated EA tools such as Rational System Architect or Abacus more or less fulfill requirements 1 through 3. But there are no tools on the market yet for making the enterprise architect’s dream of integration with all related sources of information come true. Such an unobstructed synchronization of data would be a powerful weapon in defeating the drifting apart of EA models and reality, a safeguard “that which must not, cannot be.”7

Wide-ranging IT-management tools such as alfabet’s planningIT offer EA and some of the neighboring functionality in one product offering, but they come with a price tag that is hard to sell to the chief information officer (CIO) “just for architecture.” In addition, this approach does not help if there already are other CASE8, CMDB9, or what-have-you tools installed. But even if the CIO is in a spending mood, the price tag restricts such tools to a small circle of authors since they mostly are desktop applications licensed per user.

Some creativity is required to balance the need for up-to-date EA models with the integration costs of the vision expressed in Figure 3-9. Since there are no standard integration interfaces, the realization of any synchronization arrow of the diagram in most cases means investing in custom implementation. The maxim here is to make the best of an existing blend of tools for EA purposes.

On the other hand, a manual refresh of the models is strenuous and has a slight ex post skew: just documenting what has been implemented. Manual refresh usually is a dead end because it only allows for modeling an isolated core of high-level entities. The result therefore misses an important requirement of architecture models: They should be continuous and ideally should support a seamless drill-in from high-level application landscapes to fine-grained class diagrams, project schedules, configuration parameters, operational incidents, and so on.

Finally, stale and unfertile architecture models can only be avoided by inviting a wider audience to take part in architecture concerns. This demand is expressed by requirement 5, and we’ll embark on it in Chapter 8, “Inviting to Participation.” It again stresses the importance of collaboration—this time not with adjacent information systems, as in Figure 3-9, but with the people involved in IT. Today most EA tools are pretty weak with respect to participation. They mostly support a one-directional publication by architects to the world but don’t implement feedback channels. Chapter 8 will give us an idea of how to overcome this obstacle.

The short list of requirements we’ve set out can be taken as a starting point for educated selection of an EA tool. More guidance and a checklist for tool assessment are available in, for instance, Schekkermann (2011).

Evolving the IT landscape (EA-3)

Application rationalization

When you can measure what you are speaking about and express it in numbers, you know something about it.

—Lord Kelvin (1824–1907)

In Chapter 1, we learned that Dave Callaghan, the CIO of our fictitious Bank4Us, mandated 20% savings over the next planning period in a strategic statement and explained further that:

The savings will be attributed to legacy reduction/downsizing, reduction in number of system interactions, and reduction in IT operation/support cost.

Now, Bank4Us is running more than 3,000 applications in its data centers. Such a number of applications of different generations tends to proliferate to an entanglement that resembles a rampant jungle. Ian Miller and his group of enterprise architects take the CIO’s statement as an imperative to boldly thin out this jungle. But how can they accomplish this kind of cultivation?

Identifying applications and key performance indicators

The first major step in such an initiative of application rationalization is, evidently, to get an overview of the current set of applications. As a prerequisite, there must be some guidelines that nail down what counts as an application.

Applications

What Is an Application?

Though the term application is a central notion of IT, there is no commonly accepted or precise definition of this term. The Open Group (2011) defines the term in its TOGAF standard as:

A deployed and operational IT system that supports business functions and services; for example, a payroll. Applications use data and are supported by multiple technology components but are distinct from the technology components that support the application.

This explanation leaves room for interpretation and certainly is not a sufficiently sharp delineation to come to a catalogue of enterprise applications in a straightforward manner. Further discussions are to be expected. Keller (2007) even claims that the struggle for an explicit definition of application is somewhat pointless because the domain experts working in a business unit already know their usual suspects. There’s some truth in this view, since the term application will always remain fuzzy to a degree. The identification of applications therefore needs to be backed up by the intuitions of domain experts. Nevertheless, there must be in place some guidelines that are sufficiently sharp to ensure that one doesn’t end up comparing apples with oranges across the business units. If one business unit counts single Java EARs10 as applications, a moderately complex three-tier IT system with database, business logic, and presentation tier can easily consist of 100 applications. If another unit counts such a system as a single application, the enterprise-wide comparison is out of balance.

The guidelines for identifying applications probably differ from enterprise to enterprise and certainly depend on the granularity of the enterprise’s architecture management. But as a starting point we suggest the following common traits of applications:

• They provide end-user functionality (as opposed to mere system software).

• They provide cohesive functionality having a common purpose.

• They are somewhat self-contained deployment units.

• They are logical entities in the sense that they are to some extent independent from the implementation technology.

• They have an owner who is responsible for development and maintenance.

The enterprise architects at Bank4Us are well prepared with a sufficiently up-to-date catalogue of applications at hand. In companies without an enterprise architecture practice, the composition of such a catalogue can be the first painful, laborious obstacle.

Given such a catalogue, the next step is to quantify what should be improved. This implies the agreement on some key performance indicators11 (KPIs) that one wants to optimize—numeric values that should be increased or decreased. Ian Miller and his team decide that the CIO’s directive is best measured by the following KPIs:

• Total cost of ownership (TCO) of an application. This entails all costs related to the application: Development of new features, maintenance, trouble-ticket resolution, server costs, license fees, and whatever else is on the bill for changing or running the application.

• Strategic fit (SF) of an application. This KPI tells to what extent an application is considered “legacy” on a scale from 1 to 10. It captures both technology and business aspects. An application scores high if it fits well with the envisioned business architecture, is built on standards and products that are considered future proof, and is in its prime with regard to the software life cycle.

• Value contribution (VC) of an application. This measure reflects the business value generated by the application. There are only few cases where a definite amount of money can directly be associated with an application; in most cases, the VC will be a unitless value, like strategic fit. VC summarizes the importance of the application for the business processes it supports, how well it supports them, and what revenue streams are involved in these processes. This KPI reflects the business criticality of the application as well as the impact of replacing or retiring it on the organization.

• Fan-in and fan-out of an application. The fan-in of an application A counts the different data flows entering A in the course of processes directly or indirectly supported by A. These data flows can be interface invocations by other applications, messages consumed by A, or global data structures—for instance, database tables read by A. The fan-out, on the other hand, counts how many data flows leave A. These can be interface invocations by A on other applications, messages sent out by A, or global data structures modified by A. Henry and Kafura (1981) have proposed these KPIs as measures of procedural complexity.

Ian and his team conclude that these four KPIs should suffice. Further measures just make the comparison of applications less comprehensive. They also agree on the weight each KPI should get in a comparison, and they play for a while with the idea of an all-comprising KPI-formula, such as:

![]()

But then they drop this “world formula” idea because it gives the simplistic impression that decisions could be based solely on a quantitative assessment of this variable.

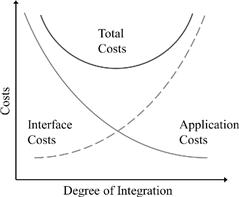

The slightly complicated fan-in and fan-out KPIs are there to capture the CIO’s statement that the number of system interactions should be reduced. They raise some discussions about why the CIO included this reduction in a strategic initiative that primarily is about cost savings. Ian explains that this is because the total costs of an application landscape are a mix of application costs and interface costs, as schematically shown in Figure 3-10.12

Figure 3-10 Application and interface costs.

The distribution of functionality to many applications results in a highly modular landscape with increased interface costs. Take, for instance, the costs to keep several versions of an application interface concurrently alive in order to serve both new and old clients—these costs do not occur, if the same functionality is integrated into a single application. But integrating widely unrelated functionality into a single application, on the other hand, also generates surplus application costs. The hardware costs, for example, are higher with each installation, and the synchronization overhead of development projects also adds to the bill. To find the proper cohesion and compromise between modularity and integration is a U-curve optimization, and the Fan-In/Fan-Out KPI’s can help quantifying it. As a general rule, only a medium Fan-In/Fan-Out value allows for a minimal Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)—both minimizing and maximizing the Fan-In/Fan-Out will at some point increase the TCO.

This exemplifies an important point about application rationalization: The KPIs to be optimized seldom are independent variables. The expectation to freely lift them all to an optimum is misleading. As Garajedaghi (2011) puts it, there is a certain slack between the variables: One variable can be modified as if it were independent in some range of tolerance, but there is an excision where it starts affecting the others.

The best thing to hope for is, therefore, some equilibrium representing a local optimum. A more practical consequence for now is that it is crucial to agree on the weight of each KPI and consider the effect of changes on the whole tuple of KPI values.

Assessing applications

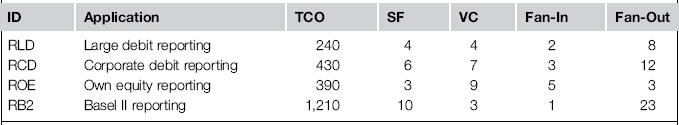

The agreement on the KPIs prepares the groundwork for assessing the applications in the application catalogue. The goal is to come up with a table like the one shown in Table 3-4.

Table 3-4 Excerpt from an Application Assessment

TCO Total cost of ownership (K $/year)

SF Strategic fit (rating 1–10)

VC Value contribution (rating 1–10)

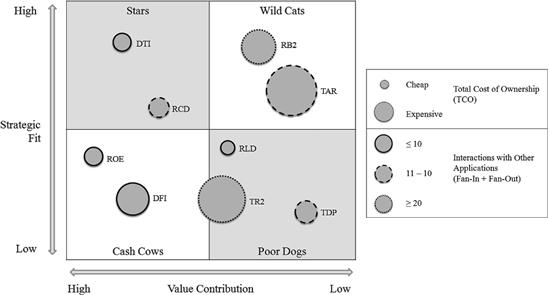

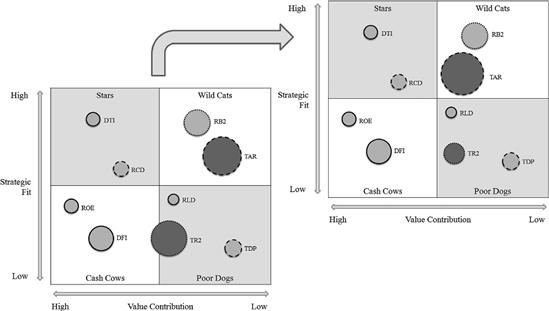

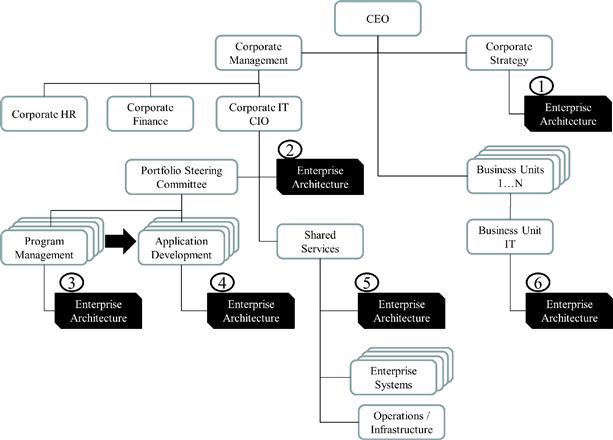

Ian picks a common scheme invented by Ward and Peppard (2003) to visualize the score of applications in four different quadrants, as shown in Figure 3-11. This scheme classifies applications into four main categories:

• The Stars ensure the current and future business of the enterprise. They are already used in important business processes and primarily support innovative products or services the company backs on as key differentiators in comparison to their competitors. Their importance for the future business is expected to grow. Furthermore, they fit well into the technology roadmap.

• The Wild Cats, sometimes also called Question Marks, have a certain potential for future business but do not contribute much to the current business operations. In a sense, these are prototypes that still have to prove their usefulness. They typically explore how new technologies can help seize new business opportunities.

• The Cash Cows form the operational backbone of the current business. They ensure today’s core operations and generate the largest share of business from IT. Any outage of such a system is a pain and is likely to end up on the CIO’s desk. But a cash cow does not fit nicely into the envisioned future operations and is technology-wise considered “legacy.”

• The Poor Dogs are not important, neither today nor in the future. In some cases they are just residues, the quick wins for an application rationalization initiative. In other cases they are support systems that are somehow needed but do not make a crucial difference to the enterprise. A typical example is an application for tracking working hours.

Figure 3-11 Ward-Peppard classification of applications.

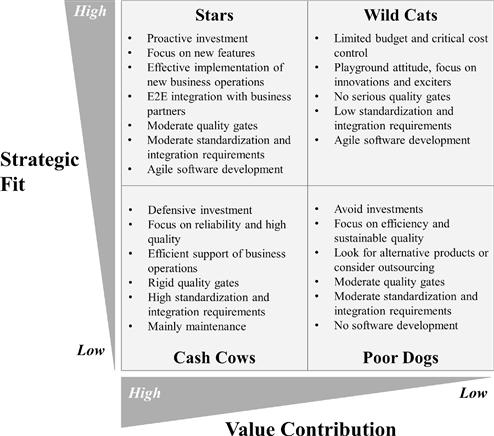

These four categories have different key quality requirements and therefore must be treated in different ways, as Figure 3-1213 indicates.

Figure 3-12 Strategies for treating various applications

It is worth highlighting that EA must show different attitudes to the four quadrants as well: Enterprise architects should not impede the capturing of crucial new ground for Stars and Wild Cats by restrictive quality gates or standardization and integration requirements. Viable applications typically run through a transition from Wild Cats over Stars to Cash Cows, and EA should foster their maturing with smoothly increasing quality constraints.

Another aspect worth noting is that the different categories of applications might claim for different approaches in software development, too. Wild Cats and Stars benefit most from agile software development because of its focus on bringing new features to life.

Cash Cows, on the other hand, are merely maintained and therefore offer no compelling reasons to switch to agile (assuming that this is not the approach the company is most acquainted and proficient with). Furthermore, the upgrade of a central Cash Cow needs extensive nonfunctional tests, requires that users and administrators are trained beforehand, and usually implies the physical rearranging of some core business processes. All this needs planning in advance, which does not fit easily into agile software development, with its functionality scoping on a three-week basis.

Stipulating how the four categories of information systems are to be treated is typically also something achieved in EA-1, “Defining the IT Strategy.” Figure 3-12 is just one typical example of such a stipulation.

Assessing alternatives

Let’s turn back to Ian’s application rationalization journey at Bank4Us. The KPI assessment of the application catalogue gave him hindsight into the applications with a high potential for optimization. The application TR2 in Figure 3-11, for example (a trading application developed in the 1990s, as far as Ian knows), is close to a Poor Dog but causes tremendous costs. Nevertheless, simply ramping it down will be an intricate matter since it shows a lot of interactions with other applications, and presumably it is deeply interwoven into the data- and workflows of the enterprise. But maybe there are other options?

Consequentially Ian’s next step is to deep dive into the refactoring options of each optimization candidate. Can a candidate be ramped down by rearranging some business processes or shifting functionality to some other applications? Can the application be refactored so that it is less interwoven with other systems? Can at least a couple of business functions be taken over by some star applications? Ian and his team discover that a small extension of the Wild Cat trading application TAR (see Figure 3-11) would make a larger part of the TR2 functionality superfluous, with only minor changes to the business processes and one additional system interaction (fan-in) added to TAR.

This appears to Ian and his team as the healthiest thing to do in comparison to other options. Hence, they redraw the architecture models, accommodate this change into the target architecture, and reassess the modified overall landscape once again, as shown in Figure 3-13.

Figure 3-13 Reassessment of a transformation.

Application rationalization is an optimization with constraints, as you can see from Ian’s reasoning. One essential constraint is that the rationalization measures must neither disrupt daily operations nor cause critical changes to the business processes or organization. Therefore, the impact of these measures must be assessed, and this will be the easier the better you have accomplished activity EA-2, Modeling the Architectures. An up-to-date EA model highlighting the relations between business processes, organizational units, services, applications, and so forth makes such an assessment a piece of cake. (Well, this statement needs to be taken with a grain of salt; it still remains a challenge, of course.)

But many enterprises are far from having such a model in place, so the assessment can really become a desperate endeavor. According to our experience, a high percentage of application rationalization initiatives fail, and they fail because of the inability to assess the impact of even humble changes. When you are consulting a company in an application rationalization and you touch the ground for the first time, you’re likely to meet ironic people telling you things like: “We have tried to ramp down application SIS in 2005 and 2007 already, and now you with your supernatural powers come to the rescue?”

The dose of sarcasm depends on the personality, but the reason for the failure of earlier attempts usually is that they unraveled so many unknown ramifications and configurations that people eventually decided they’d better not touch anything. Chapter 1 already reported on highly respected enterprises that lost track of their IT to such an extent that the lunatic “hotline approach” becomes an acceptable reengineering method: Install an emergency phone right beneath the application server, shut the server down, and wait to see who calls.

The Bank4Us example also illustrates that application rationalization is a recursive process. Options that seem promising and feasible are applied to the architecture model, and the resulting target landscape is reassessed using the same KPIs as in the first round. Since the target landscape is just a vision and not operational, one is relying on guesswork here more than usual. But the effect of an improvement must be quantified somehow.

The guesswork character of this projection into the future brings us to an important question: How are the KPI values actually calculated? How did Ian and his team come to the conclusion that the return on equity (ROE) application has a TCO of $390,000 per year but a poor strategic fit of three?

The answer in brief is: Facts and opinions. A concrete indicator such as TCO can mostly be calculated on the basis of facts—by gathering the bills and contracts pertinent to the application under inspection or by collecting maintenance efforts from incident management systems and similar sources. But the evaluation of an imaginary measure such as strategic fit (SF) mostly relies on opinions. To gather them, Ian and his team have conducted a series of interviews with subject matter experts with different responsibilities: business and IT strategists, application owners, software developers, and operating personnel.

But the question “How well do you think the application fits to the strategy?” is too abstract for a non-erratic answer. Most people will shrug their shoulders. Ian therefore decomposes the SF-KPI into about two dozen base indicators and places them on a scorecard, as shown in Table 3-5.

Table 3-5 Excerpt of a Scorecard to Estimate the KPI Strategic Fit

| ID | Base Indicator | Score (1–10) |

| BI1 | The application fits into the technology road map | 5 |

| BI2 | The application supports the strategic goal of customer empowerment | 3 |

| BI3 | The application supports multichanneling and mobile devices | 3 |

| BI4 | The application resolves an existing business impediment | 7 |

The scores of the individual base indicators are then aggregated according to some weighted formula to the KPI value of SF.

In collecting opinions, it is crucial whom you decide to ask. The prevalent approach is to nominate subject matter experts and conduct interviews with them. This narrows the circle to a small, illustrious group of adepts whose judgments are hopefully full to the brim with insight. But if the majority of users say that a certain application is cumbersome, the experts’ praise of it is to be taken with care. Chapter 8, “Inviting to Participate,” therefore suggests complementary means of Enterprise 2.0 to come to a broader, balanced assessment.

Summary

Application rationalization is one special but prevalent example of EA-3, Evolving the IT Landscape. It also is an example of a transformation that is not driven by tangible functional requirements but by nonfunctional strategic concerns such as reducing costs or complexity. We have seen how KPIs are the pivotal tool to drive such transformations, right in the spirit of the often-cited tenet by Peter F. Drucker14 that “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” They are the key to a precise understanding of the goals, crucial for identifying areas of improvement, and simulating the effect of changes. We also saw how deep dives into areas of improvement depend on how well an enterprise maintains its knowledge about its IT. Only if a sufficiently accurate and up-to-date model of the enterprise architecture is available, one can assess the impact of changes and simulate their costs and benefits.

General IT transformations

The evolution of the IT landscape is not only driven by strategic initiatives—that’s a pivotal thing to note when we’re looking at IT transformations in general. What we mean by strategic initiative is something like Ian’s rationalization project at Bank4Us: The CIO issues a strategic goal, the enterprise architects work out a target architecture matching this goal, identify what has to be done, and mandate the vassals in the development and operational departments to put things into practice.

In most enterprises we have seen so far, these strategic initiatives are not even the main force having an effect on the IT landscape. The decision of an automotive company to intensify marketing by adopting mobile devices or the plan of an ocean carrier to open a wide range of B2B services to logistics partners do not typically stem from the strategic board. In companies with good strategic governance, such initiatives are in line with the strategic direction, but they are nevertheless brought to the table and owned by business units. They also can bypass the desk of enterprise architects: The initiatives are run as business projects, and the target architecture consequentially is in the hands of project architects, who by majority do not belong to the EA group.

The IT metamorphoses that enterprise architects encounter in practice are therefore a mix: In a few initiatives they are the masterminds; in a lot of others, planning and design is out of their hands. In those cases not owned by EA, the role of enterprise architects is limited to taking care that the evolution stays within strategic boundaries (see EA-5, Developing and Enforcing Standards and Guidelines) and to “backfilling” the architecture by integrating the solutions designed by others into the overall picture (see EA-6, Monitoring the Project Portfolio). The development of an IT landscape resembles more of a true evolution, where different actors and purposes try to push their business through, rather than a transformation planned by some mastermind.

Another peculiarity of Ian’s rationalization project is that it takes applications as a focal point. Applications traditionally are the units of ownership, deployment, and maintenance; they also are things that are internally well known and distinguishable as icons on the company desktops. But they are not the only possible focal point, maybe not even the best one in a modern architecture.

Dave Callaghan, the CIO of Bank4Us, also mandated customer empowerment as a strategic goal. But the customer view comprises products, contracts, services, business user interfaces, or customer processes. The enterprise’s applications are aliens from this viewpoint.

Wouldn’t it therefore be more natural to take the business architecture as a point of departure, instead of immediately gazing at applications? Then, the paramount step toward customer empowerment would be to draw a picture of the as-is landscape of services, business interfaces, and products and to design an improved to-be landscape offering more functions, processes, and a lighter access. Only the second step would then jump to applications and explore the options to support the envisioned business architecture by application functions and collaborations.

This is roughly the order prescribed by the TOGAF Architecture Development Method (ADM), which we take a closer look at in Chapter 4, “Architecture Frameworks.” The last step in ADM, leading to a full blueprint of the CIO’s customer empowerment mission, is mapping the application architecture to technologies—the software components, third-party products, standards, servers, routers, and what else there is when getting down to the nitty-gritty. This priority order—from business architecture over applications to technology—shifts the focus from a technology-centric to a business-centric design. It better fits initiatives that have a business momentum instead of an IT momentum, such as bringing down application costs.

The strong use of KPIs is the last peculiarity of application rationalization that needs to be differentiated when we’re looking at IT transformations in general. Many strategic goals are qualitative by nature, as we can see from the Bank4Us goal of customer empowerment, and their translation into quantitative values seems rather artificial.

Often the assessment of target landscapes simply compares the different alternatives against a checklist of requirements. Compliance is noted by a checkmark, and the pros and cons of exceptions are discussed with regard to contents but without referring to numeric values. Nevertheless, it is worth striving for a KPI representation of qualitative goals, even if they are just unitless score values, as shown in Table 3-7. Three primary reasons count in favor of quantification:

• The compliance with a generic goal, such as customer empowerment, usually is not a matter of “either/or” but of “more or less.” There are many shades of gray between “black” solutions that do not empower customers at all and “white” ones that make customers crowned regents. These shadings can only be captured by numbers.

• The assessment of alternative target architectures in EA covers a large area of the IT landscape. The cases in which one alternative outplays the others in all dimensions are rare and do not cause much headache. It becomes interesting if an alternative offers more customer empowerment in some applications but scores lower in others. In such a case, some aggregation algorithm is needed to come to a holistic comparison.

• The formulation of KPIs sharpens the understanding of a goal. This is in line with Lord Kelvin’s tenet that the ability to express something in numbers signals a deeper understanding of the subject. Qualitative is sometimes just a euphemism for fuzzy.

SOA transformations

Transformations toward a service-oriented architecture (SOA) belong to the more technically driven changeovers of the IT landscape one frequently encounters today. Some time ago there was a debate about the slogan “SOA is dead,” put into the world by the Burton Group (Manes, 2009). Still, the larger firms we’ve seen over the past few years have kept SOA on their strategic agendas.

For good reason, SOA is a very suitable architecture paradigm for designing large software systems. The proposed next-generation replacements, such as Sam Ruby’s Resource Oriented Architecture (ROA) (Richardson and Ruby, 2007), did not make it to the enterprise IT agenda. Maybe this is because they are not true replacements of SOA but instead are necessary extensions of a too narrow understanding of “services.” The term service had found a rather one-sided interpretation by the WS-*15 Web services and the extension to REST16 and other implementation styles of “service,” which is the core of ROA, WOA, MOA17 (and so on) just correct this narrow-mindedness.

But a truth behind the provocative “SOA is dead” is that SOA certainly is past its peak of inflated expectations. Today it will be difficult to find sponsors and followers for an initiative that turns the whole enterprise IT upside down just for the sake of SOA. If SOA is still on the agenda, it is an architecture standard for changes that are needed for other reasons, but not an end in its own right. For example, the ocean carrier striving for a B2B integration with its logistics partners will probably build a solution in the SOA way. As a side effect, the IT landscape moves closer to SOA in that case.

Nevertheless, there are considerable advantages of SOA, regardless of any hype cycles:

• Business-centric design. A good SOA design sets the priority on business capabilities and processes.

• Reuse of functionality. SOA services expose functionality with a potential for wider cross-organizational use. The SOA paradigms of encapsulation, statelessness, and service-level agreements help in utilizing existing assets in many contexts. Furthermore, SOA services have a coarse granularity and thereby avoid the felt-like weave of distributed interactions that made earlier attempts with distributed objects (e.g., CORBA18) fail.

• Flexibility. SOA clearly separates control logic from business logic and data: The control logic is incorporated in processes, whereas business logic and data are made available by services. This allows for a flexible mapping between the two parts of the game; ideally, processes can be rearranged without much impact on the services, and vice versa.

• Multichanneling. SOA also separates the presentation logic from control logic, business logic, and data. This implies that the business processes, functionality, and data are no longer bound to a particular end-user application. You can start a process from your desktop, take the next step with your smartphone, and receive progress reports via Short Message Service (SMS).

• Decoupling of functionality and technology. Business architecture and technologies have different life cycles. The technology-agnostic concepts of SOA introduce a level of abstraction that protects the business functionality from heterogeneity and change in the underlying technical infrastructure.

• Stability. The SOA concept of loose coupling and the corresponding techniques stabilize the IT landscape. Outages and performance fall-offs become locally isolated and no longer drag along contiguous applications.

The business-centric design aligning business processes and services with underlying application functionality makes SOA an ideal ally for EA. Both have business-IT alignment on their primary agenda. “SOA provides a unique chance for the first time in IT history to create artifacts that have enduring value for both, the business as well as the technology side,” write Krafzig, Banke, and Slama (2006). They see SOA as an approach for renovating the IT landscape and SOA governance as a means of enterprise architecture management. But given that the IT landscape consists of vast areas with good old mainframes and other assets far off from service orientation, it should be clear that EA must have a much wider scope.

Assessing and building capabilities (EA-4)

Draupadi,19 the heroine of the Indian epic Mahabharat, emerged as a full-grown woman from the sacrificial fire (Yagnya), and proclaimed to the whole world that she was immaculate. Unfortunately, we do not have any such mechanism to produce fully equipped enterprise architects “just like that.” The scarcity of enterprise architects (or the right IT resources in the right positions, in general) is quite evident in the IT industry. Despite attractive offers, many IT positions remain open, waiting long for “true love’s kiss.” In some cases, they are inappropriately filled, and in some others their tasks are silently stapled to the job descriptions of the enterprise architects.

The face of IT is changing continuously and rapidly. On the one hand, it is becoming more commoditized, centralized, and outsourced. On the other hand, IT is venturing into providing value-added services to the business, like business process design, product design, business transformation and innovation. As a consequence, the portfolio of IT service offerings is expanding, and IT leadership is becoming more and more crucial. Ross (2011) states:

If, despite the emergence of a digital or information economy, the business leaders are not positioned to lead IT-enabled business transformations (…), the need for IT to do so becomes acute (…). Ensuring the right talent to realize the IT organization’s ambitions is a critical challenge, many CIOs told us.

The question on the CIO’s table is: Is the current workforce equipped to adjust quickly and effectively to the challenges ahead? The activities in the IT unit are gearing toward business process engineering, architecture realization, and program management. This goes far beyond mere application development, system implementation, and project management, which were sufficient only a few years ago.

As a consequence, enterprises are realizing the importance of strategic competency management—an antithesis to the reactive demand fulfillment of the past. In the ideal case, they actively look at the future possibilities, demands, and constraints in the organization. This means developing long-term workforce plans, defining multiple career paths, investing heavily in their people, facilitating internal and external training programs, and offering rotations between business and IT roles.

Competence development for enterprise architects

In the first century BC, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio20 described an ideal architect as follows:

A man of letters, a skilled draftsman, a mathematician, familiar with historical studies, a diligent of philosophy, acquainted with music, not ignorant of medicine, earned in the responses of juris consultis, familiar with astronomy and astronomical calculations.

Today the image of an enterprise architect in IT continues to be loyal to this 2,000-year-old definition—in the sense that an enterprise architect in today’s information age is perceived as a multidimensional personality. She knows a lot of things and can do many things. The role of enterprise architect entails:

• Making important and (quite often) difficult decisions single-mindedly, to ensure the conceptual integrity of the enterprise’s business and IT; moreover, she needs to take those decisions early enough so that a plan is in place for everyone else to follow (see Activities EA-1, EA-2, and EA-3).

• Being cognizant to what is going on in the projects, watching out for important issues, and addressing them before they get out of control; at the same time, she has to work in intense collaboration across the projects (see Activities EA-5, EA-6, EA-7, and EA-8).

• Communicating at technical and nontechnical levels with conviction and restraint; quite often this requires us to stand up in a meeting and convey bad news to the sponsors or stakeholders in the most sensible manner (relates to all Activities EA-1 through EA-8).

• Keeping the organization on-ramp and on par with technology advancement in the industry (see Activities EA-1, EA-3, EA-5, and EA-6).

In a nutshell, the role of enterprise architect demands a plethora of multidisciplinary skills. This includes hard skills such as business acumen, technology expertise, and project management. Even more important are soft skills such as executive communication, collaborative influence, and organizational leadership.

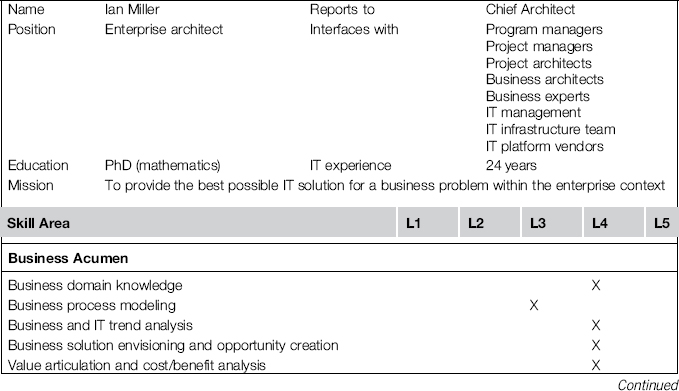

Competency tree for an enterprise architect

The first step in profiling an enterprise architect is to build a competency tree. This means identifying the competency areas relevant to the enterprise architecture, organizing them in a structure, and defining associated proficiency levels.

A competency area entails the body of knowledge pertaining to a subject or a field of study. These can be areas as different as customer relationship management, enterprise data management, integration patterns, Web 2.0, agile methodology, or project management. The proficiency levels help measure an individual’s depth of knowledge and level of experience in a given competency area. The competency areas for an architect can typically be grouped under four main capability streams:

• Business acumen. This pertains to an individual’s knowledge, skills, and experience in the specific business domain under consideration. For instance, the IT organization in Bank4Us needs broad and deep insight into the banking domain, ranging from the basic account-opening process in retail banking up to risk analysis and hedging of exotic derivative products in investment banking.

• Technical expertise. This of course is the core competence required for any IT organization. It depends on the technology environment of the enterprise as to what expertise is required there. In Bank4Us, deep know-how in mainframe, Java/JEE, packaged CRM, Unix/C, and relational database management systems (RDBMS) such as Oracle, DB2, and MS SQL Server are valued.

• Process excellence. This deals with the knowledge about main IT processes, comprising software engineering (for example, agile and waterfall), quality management, operational management (e.g., ITIL), program management, investment and risk management, procurement, and vendor relationship management.

• Organizational leadership. This area primarily comprises people and behavioral skills pertaining to team leadership, intense collaboration, communication, and negotiation.

A balanced competence framework should list about 10 relevant competency areas for each of the preceding capabilities. If needed, this structure can be further enhanced—for instance, by decomposing a competency area into a three-level tree showing a subject area (root), topics (branches), and learning modules (leaves). Such a tree is specific to the skills and experience requirements in a given enterprise and needs to be set up with hindsight into the context of market opportunities, organizational needs, and environmental constraints of that enterprise.

Having defined the competency tree, the proficiency of an individual in a given competency area can be ranked using a set of evaluation criteria. Here is a suitable scale of five levels:

• Level 1. Limited knowledge, basic awareness.