Operations Security

This chapter covers operational security. We talk about the history of operational security, which reaches at least as far back as the writings of Sun Tzu in the sixth century BC, to the words of George Washington, writings from the business community, and formal methodologies from the US government. We talk about the five major steps of operations security: identifying critical information, analyzing threats, analyzing vulnerabilities, determining risks, and planning countermeasures. We also go over the Laws of OPSEC, as penned by Kurt Haas. In addition to discussing the use of operations security in the worlds of business and government, we address how it is used in our personal lives, although perhaps in a less formal manner.

Keywords

Competitive counterintelligence; competitive intelligence; competitive strategy; George Washington; Laws of Operations Security; operations security; Purple Dragon; risks; Sun Tzu; threats; Vietnam War; vulnerabilities

Information in This Chapter

• Origins of operations security

• The operations security process

Introduction

Operations security, known in military and government circles as OPSEC, is, at a high level, a process that we use to protect our information. Although we have discussed certain elements of operations security previously, such as the use of encryption to protect data, such measures are only a small portion of the entire operations security process.

Alert!

Although the formal methodology of operations security is generally considered to be a governmental or military concept, the ideas that it represents are useful not only in this setting but also in the conduct of business and in our personal lives. Throughout the chapter, when we discuss the specific government use of operations security, we will refer to it as OPSEC, and outside of that specific use as operations security, in order to differentiate between the general concept and the specific methodology. The practices include what kind of information we disclose in social media, what tell our friends and family, and how we handle data.

The entire process involves not only putting countermeasures in place, but before doing so, carefully identifying what exactly we need to protect, and what we need to protect it against. If we jump directly to putting protective measures in place, we have put the cart before the horse and might not be directing our efforts toward the information assets that are actually the most critical items to protect. It is important to remember when putting security measures in place that we should be implementing security measures that are relative to the value of what we are protecting. If we evenly apply the same level of security to everything, we may be overprotecting some things that are not of high value and underprotecting things of much greater value.

Origins of operations security

Operations security (OPSEC) may be a fairly recent term but the concepts comprising it are truly ancient indeed. We can see such ideas put forth in the works of Sun Tzu thousands of years ago, and in the words of the founders of the United States, such as George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. While we can point to nearly any period in history, and nearly any military or large commercial organization, and find the principles of operations security present, a few specific occasions present themselves as being particularly influential in the development and use of operations security. While this book is about security and not warfare, it is worth looking at these principles as we are in a constant battle with the threat to protect our data.

Sun Tzu

Sun Tzu was a Chinese military general who lived in the sixth century BC. Among those of a military or strategic bent, Sun Tzu’s work The Art of War is considered one of the foundational doctrinal texts for conducting such operations. The Art of War has spawned countless clones and texts that apply the principles it espouses to a variety of situations, including, but not limited to, information security. The text provides some of the earliest examples of operations security principles that are plainly stated and clearly documented.

We can point out numerous passages within The Art of War as being related to operations security principles. We will look at just a couple of them for the sake of brevity.

The first passage is “If I am able to determine the enemy’s dispositions while at the same time I conceal my own, then I can concentrate and he must divide” [1]. This is a simple admonition to discover information held by our opponents while protecting our own. This is one of the most basic tenets of operations security.

Additional resources

The Art of War is a great resource for those who are involved in information security and is definitely a recommended read. A paper copy can be found at most any good bookstore, and an online version is available for free on the Project Gutenberg Web site, www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/132.

The second passage is “(when) making tactical dispositions, the highest pitch you can attain is to conceal them; conceal your dispositions, and you will be safe from prying of the subtlest spies, from the machinations of the wisest brains” [1]. Here, Sun Tzu is saying we should conduct our strategic planning in an area that is very difficult for our opponents to observe, specifically the highest point we can find. Again, this is a recommendation to very carefully protect our activities so that they do not leak to those that might oppose our efforts. For having been penned such a long time ago, the writings of Sun Tzu, as they relate to operations security, are still applicable to this day.

George Washington

George Washington, the first president of the United States, was well known for being an astute and skilled military commander and is also well known for promoting good operational security practices. He is known in the operations security community for having said, “Even minutiae should have a place in our collection, for things of a seemingly trifling nature, when enjoined with others of a more serious cast, may lead to valuable conclusion” [2], meaning that even small items of information, which are valueless individually, can be of great value in combination. We can see an example of exactly this in the three main items of information that constitute an identity: a name, an address, and a Social Security number. Individually, these items are completely useless. We could take any one of them in isolation and put it up on a billboard for the world to see, and not be any worse for having done so. In combination, these three items are sufficient for an attacker to steal our identity and use it for all manners of fraudulent activities. This is the foundation of OPSEC as the focus in on unclassified data that when correlated becomes data that should be classified. For example, IP addresses are not classified and the fact that the Missile Defense Command has an Operations Center is not classified, however, the specific IP address used by the Operations Center is classified.

Washington is also quoted as having said, “For upon Secrecy, Success depends in most enterprises of the kind, and for want of it, they are generally defeated” [3]. In this case, he was referring to an intelligence gathering program and the particular need to keep its activities secret. He is often considered to have been very well informed on intelligence issues and is credited with maintaining a fairly extensive organization to execute such activities, long before any such formal capabilities existed in the United States. We call this business intelligence today and many of the same actives go on. At the national level, we have organizations like NSA/CIA going against China’s Advance Persistent Threat (APT) today.

Vietnam War

During the Vietnam War, the United States came to realize that information regarding troop movements, operations, and other military activities was being leaked to the enemy. Clearly, in most environments, military or otherwise, having our opponents gain foreknowledge of our activities is a dangerous thing, particularly so when lives may be at stake. In an effort to curtail this unauthorized passing of information, a study, codenamed Purple Dragon, a symbol of OPSEC that persists to this day, as shown in Figure 7.1, was conducted to crack down the cause.

Ultimately, the study brought about two main ideas: first, in that particular environment, eavesdroppers and spies abounded; and second, a survey was needed to get to the bottom of the information loss. The survey asked questions about the information itself, vulnerability analysis, and other items. The team conducting these surveys and analyses also coined the term operations security and the acronym OPSEC. Additionally, they saw the need for an operations security group to serve as a body that would espouse the principles of operations security to the different organizations within the government and work with them to get them established, but this was not to happen until much later. Today for units deployed to operational theaters, both the units and their families receive OPSEC training and assessments.

Business

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, some of the OPSEC concepts that were used in the world of the military and government were beginning to take root in the commercial world. The ideas of industrial espionage and spying on our business competition in order to gain a competitive advantage have been around since the beginning of time, but as such concepts were becoming more structured in the military world, and they were becoming more structured in the business world as well. In 1980, Michael Porter, a professor at Harvard Business School, published a book titled Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. This text, now nearing its 60 printing, set the basis for what is referred to as competitive intelligence.

Competitive intelligence is generally defined as the process of intelligence gathering and analysis in order to support business decisions. The counterpart of competitive intelligence, competitive counterintelligence, correlates in a fairly direct manner to the operations security principles that were laid out by the government only a few years previously and is an active part of conducting business to this day. We can see these principles at work in many large corporations as well as in groups such as the Strategic and Competitive Intelligence Professionals (SCIP)1 professional organization and the Ecole de Guerre Economique, or Economic Warfare School, located in Paris. A quick Google will also show a number of companies and tools that offer “business intelligence” or “competitive intelligence.” It is worth noting that a company that hires someone or has a zealous employee gather intelligence maybe held responsible for the methods they use (i.e., hacking into competition and stealing the information).

Interagency OPSEC support staff

After the end of the Vietnam War, the group that conducted Purple Dragon and developed the government OPSEC principles tried to get support for an interagency group that would work with the various government agencies on operations security. Unfortunately, they had little success in interesting the various military institutions and were unable to gain official support from the US National Security Agency (NSA). Fortunately, through the efforts of the US Department of Energy (DOE) and the US General Services Administration (GSA), they were able to gain sufficient backing to move forward. At this point, a document was drafted to put in front of then-first-term-President Ronald Reagan.

These efforts were delayed due to Reagan’s reelection campaign, but shortly afterward, in 1988, the Interagency OPSEC Support Staff (IOSS) was signed into being with the National Decision Security Directive 298 [4]. The IOSS is responsible for a wide variety of OPSEC awareness and training efforts, such as the poster shown in Figure 7.2.

The operations security process

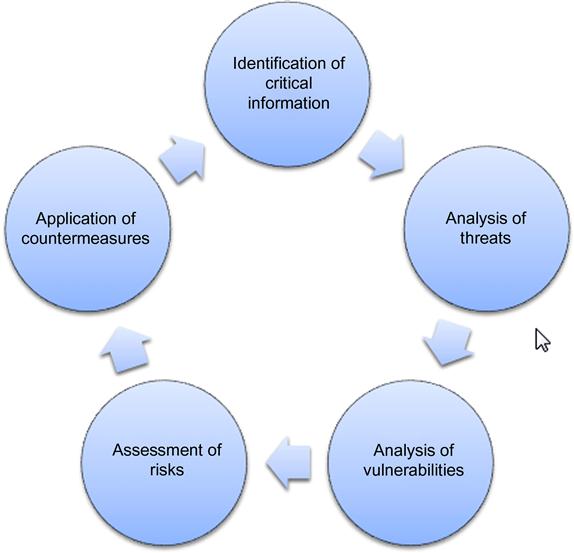

The operations security process, as laid out by the US government, will look very familiar to anyone who has worked with risk management. In essence, the process is to identify what information we have that needs protection, analyze the threats and vulnerabilities that might impact it, and develop methods of mitigation for those threats and vulnerabilities, as shown in Figure 7.3.

Although the process is relatively simple, it is very effective and time tested.

Identification of critical information

The initial step, and, arguably, the most important step in the operations security process, is to identify our most critical information assets. Although we could spend a great deal of time identifying every little item of information that might even remotely be of importance, this is not the goal in this step of the operations security process. For any given business, individual, military operation, process, or project, there are bound to be at least a few critical items of information on which everything else depends. For a soft drink company it might be our secret recipe, for an application vendor it might be our source code, for a military operation it might be our attack timetable, and so on. These are the assets that most need protection and will cause us the most harm if exposed, and these are the assets we should be identifying.

Analysis of threats

As we discussed in Chapter 1, when we covered threats, vulnerabilities, and risks, a threat is something that has the potential to cause us harm. In the case of analyzing threats to our information assets, we would start with the critical information we identified in the previous step. With the list of critical information, we can then begin to look at what harm or financial impact might be caused by critical information being exposed, and who might exploit the exposure. This is the same process used by many military and government organizations to classify information and determine who is allowed to see it.

For instance, if we are a software company that has identified the proprietary source code of one of our main products as an item of critical information, we might determine that the chief threats of such an exposure could be exposure to attackers and to our competition. If the source code were exposed to attackers, they might be able to determine the scheme we use to generate license keys for our products in order to prevent piracy and use access to the source code to develop a utility that could generate legitimate keys, thus costing us revenue to software piracy. In the case of our competition, they might use access to our source code to copy features for use in their own applications, or they might copy large portions of our application and sell it themselves.

This step in the process needs to be repeated for each item of information we have identified as being critical, for each party that might take advantage of it if it were exposed, and for each use they might make of the information. Logically, the more information assets we identify as being critical, the more involved this step becomes. In some circumstances, we may find that only a limited number of parties are capable of making use of the information, and then only in a limited number of ways, and in some cases we may find the exact opposite. This type of analysis is highly situational.

Analysis of vulnerabilities

As with our discussion on threats, we also talked about vulnerabilities in Chapter 1. Vulnerabilities are weaknesses that can be used to harm us. In the case of analyzing the vulnerabilities in the protections we have put in place for our information assets, we will be looking at how the processes that interact with these assets are normally conducted, and where we might attack in order to compromise them. When we looked at threats, we used the source code of a software company as an example of an item of critical information that might cause us harm if it were to find its way into the hands of our competition.

When we look at vulnerabilities, we might find that our security controls on the source code with which we are concerned are not very rigorous, and that it is possible to access, copy, delete, or alter it without any authorization beyond that needed to access the operating system or network shares. This might make it possible for an attacker who has compromised the system to copy, tamper with, or entirely delete the source code, or might render the files vulnerable to accidental alteration while the system is undergoing maintenance. We might also find there are no policies in place that regulate how the source code is handled, in the sense of where it should be stored, whether copies of it should exist on other systems or on backup media, and how it should be protected in general. In the worst-case scenario, we could find out there was a compromise but not have the infrastructure or skills to determine what the real damage was. These issues, in combination, might present multiple vulnerabilities that could have the potential to lead to serious breaches of our security.

Assessment of risks

Assessment of risks is where the proverbial rubber meets the road, in terms of deciding what issues we really need to be concerned about during the operations security process. As we discussed in Chapter 1, risk occurs when we have a matching threat and vulnerability, and only then. To go back to our software source code example, we had determined that we had seen a threat in the potential for our application source code being exposed in an unauthorized manner. Furthermore, we found that we had a threat in the poor controls on access and configuration/version management to our source code, and a lack of policy in how exactly it was controlled. These two matching issues could potentially lead to the exposure of our critical information to our competitors or attackers.

It is important to note again that we need a matching threat and vulnerability to constitute a risk. If the confidentiality of our source code was not an issue—for instance, if we were creating an open source project and the source code was freely available to the public—we would not have a risk in this particular case. Likewise, if our source code were subject to very stringent security requirements that would make it a near impossibility for it to be released in an unauthorized manner, we would also have minimal risk but usually at high security costs. Speed, quality of security, and cost must always be balanced.

Application of countermeasures

Once we have discovered what risks to our critical information might be present, we would then put measures in place to mitigate them. Such measures are referred to in operations security as countermeasures. As we discussed, in order to constitute a risk, we need a matching set of threats and vulnerabilities. When we construct a countermeasure for a particular risk, in order to do the bare minimum, we need only to mitigate either the threat or the vulnerability. In the case of our source code example, the threat was that our source code might be exposed to our competitors or attackers, and the vulnerability was the poor set of security controls we had in place to protect it. In this instance, there is not much that we can do to protect ourselves from the threat itself without changing the nature of our application entirely, so there is really not a good step for us to take to mitigate the threat. We can, however, put measures in place to mitigate the vulnerability.

In the case of our source code example, we had a vulnerability to match the threat because of the poor controls on the handling of the code itself. If we institute stronger measures on controlling access to the code and also put policy in place to lay out a set of rules for how it is to be handled, we will largely remove this vulnerability. Once we have broken the threat/vulnerability pair, we will likely no longer be left with much in the way of a serious risk.

It is important to note that this is an iterative process; once we reach the end of the risk evaluation cycle, we will, in all likelihood, need to go through the cycle more than once in order to fully mitigate any issues. We may also need to conduct the evaluations at a granular level on different aspects of the program. Each time we go through the cycle, we will do so based on the knowledge and experience we gained from our previous mitigation efforts, and we will be able to tune our solution for an even greater level of security. In addition, when our environment changes and new factors arise, we will need to revisit this process.

For those familiar with the risk management process, we might notice a missing step from the operations security side when comparing the two processes, namely, an evaluation of the effectiveness of our countermeasures. It is the author’s belief that this is implied in the operations security process. However, the process is certainly not set in stone and there is absolutely no reason not to formally include this step if it is desired. In fact, we may see great benefit from doing so.

Haas’ Laws of operations security

As a somewhat different, and briefer, viewpoint on the operations security process, we can look at the Laws of OPSEC, developed by Kurt Haas while he was employed at the Nevada Operations Office of the DOE. These laws represent a distillation of the operations security process we discussed earlier and, while we might not necessarily call them the most important parts of the process, they do serve to highlight some of the main concepts of the overall procedure.

First law

The first law of operations security is “If you don’t know the threat, how do you know what to protect?” [5]. This law refers to the need to develop an awareness of both the actual and potential threats that our critical data might face. This law maps directly to the second step in the operations security process.

Ultimately, as we discussed earlier, we may face many threats against our critical information. Each item of information may have a unique set of threats and may have multiple threats, each from a different source. Particularly as we see the surge of services that are cloud-based, it is also important to understand that threats may be location dependent. We may have enumerated all the threats that face our critical data for a particular location, but if we have our data replicated across multiple storage areas in multiple countries due to a cloud-based storage mechanism, threats may differ from one storage location to another. Different parties may have better or easier potential access in one particular area, or the laws may differ significantly from one location to another and pose entirely new threats.

More advanced

Cloud computing refers to services that are hosted, often over the Internet, for the purposes of delivering easily scaled computing services or resources. Cloud-based services often use a hardware and network infrastructure that is spread over many devices in a widely distributed fashion, often spanning geographic borders. We can see examples of cloud-based offerings from many companies at present, including Google, Microsoft, IBM, and Amazon, just to name a few. The security of cloud services and the data they contain is very much a hot topic in the information security world at present and will likely continue to be for some period of time. Depending on the data and services we are considering hosting in an environment that is largely out of our direct control, the risk may be considerable.

Not only is it important to understand the threats and sources of threats themselves, but it is also important to understand the repercussions of exposure in a specific situation so that we can plan our countermeasures for that particular occurrence very specifically.

Second law

“If you don’t know what to protect, how do you know you are protecting it?” [5]. This law of operations security discusses the need to evaluate our information assets and determine what exactly we might consider to be our critical information. This second law equates to the first step in the operations security process.

In the vast majority of government environments, identification and classification of information is mandated. Each item of information, perhaps a document or file, is assigned a label that attests to the sensitivity of its contents, such as classified, top secret, and so forth. Such labeling makes the task of identifying our critical information considerably easier, but is, unfortunately, not as frequently used outside of government. In the business world, we may see the policy that dictates the use of such information classification, but, in the experience of the author, such labeling is usually implemented sporadically, at best. A few civilian industries, such as those that deal with data that has federally mandated requirements for protection (financial data, medical data), do utilize information classification, but these are the exception rather than the rule.

Third law

The third and last law of operations security is “If you are not protecting it (the information), … THE DRAGON WINS!” [5]. This law is an overall reference to the necessity of the operations security process. If we do not take steps to protect our information from the dragon (our adversaries or competitors), they win by default.

The case of the “dragon” winning—from the constant appearance of security breaches reported by the news media and on Web sites that track breaches, such as www.datalossdb.org appears to be unfortunately common. In many cases, we can examine a breach and find that it was the result of simple carelessness and noncompliance with the most basic security measures and due diligence. We can see an example of exactly this in a breach announced by California’s Stanford University in June 2013.

In this instance, the university exposed information containing the name, medical record number, age, telephone number, and information on medical procedures on more than 12,000 patients at the Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital [6]. Although we might assume that a wily band of hackers had subverted the university’s stringent security measures and managed to steal a copy of the database from a protected system on the university network, this is sadly not the case. The patient data was located on an unencrypted laptop, which was subsequently stolen.

In such cases, the operations security process, when properly followed, will quickly point out critical data sets such as these, enabling us to stand a much better chance of avoiding such a situation. The security measures needed to prevent breaches such as those we discussed in the Tulane example are neither complex nor expensive and can save us a great deal of reputational and financial damage by taking the few steps needed to put them in place.

Operations security in our personal lives

Although we have discussed the use of the operations security process in both business and government throughout this chapter, it can also be of great use in our personal lives. Although we might not consciously and formally step through all the steps of the operations security process to protect our personal data, we still do use some of the methods we have discussed.

For example, if we will be going on vacation for several weeks and will be leaving behind an empty house for the whole time, the steps we take to ensure some level of security while we are gone will generally map very closely to the operations security process. We might take a few minutes to think about the indicators that the house is unoccupied and vulnerable:

• Told everyone on Facebook we were going

• Posts to twitter while we are on vacation about what we are doing

• No noise coming from the house when we would normally be home

• Newspapers building up in the driveway or stopped

We might also take steps to ensure that we do not present such an obvious display of vulnerabilities to those that might threaten the security of our domicile, namely, burglars or vandals. We might set timers on our lights so that they turn on and off at various times throughout the house. We may also set a timer on the television or radio so that we can generate noise consistent with someone being home. In order to solve the problem of mail and newspapers stacking up, we can have the delivery of them suspended while we are gone. To give the appearance of occupation, we might also have a friend drop by every few days to water the plants and check on things, perhaps moving a car in and out of the garage every now and then. Finally we need to be aware what everyone is the group is posting to social media and hold off on telling unrestrained/untrusted groups what we are doing until after the trip.

Alert!

In the age of social networking tools, one particular personal operations security violation can be seen on a disturbingly regular basis. Many such tools are now equipped with location awareness functionality that can allow our computers and portable devices to report our physical location when we update our status. Additionally, many people are fond of adding notifications that they are going to lunch, leaving on vacation, and so on. In both of these instances, we have left the general public, and potentially, attackers, a very clear signal of when we might not be home, when we might be found at a particular location, and so forth. From an operational security standpoint, this is ill-advised.

Although such steps are clearly not strictly regimented and militaristic in nature, such as we might find with OPSEC being implemented by the government, the process is the same. Most of us follow such processes when we protect our physical property due to the obvious nature of the threat, but we also need to take care to protect ourselves in the logical sense.

In our daily lives, our personal information goes through a staggering variety of computer systems and over a large number of networks. Although we might take steps to ensure that we mitigate security threats by being careful about where and how we share our personal information over the Internet, shredding mail that contains sensitive information before throwing it away, and other similar measures, we are, unfortunately, not in control of all the places our personal information might be exposed.

As we pointed out with the Stanford breach example earlier in this chapter, not everyone will take the same care with our information. In such cases, if we have planned for the security of our personal data in advance, we can at least mitigate the issue to a certain extent. We can put monitoring services in place to watch our reports with the credit reporting agencies, we can file fraud reports with these same agencies in the case of a breach, we can very carefully watch our financial accounts, and other similar measures. Although such steps might not be complex, or terribly difficult to carry out, they are better done in advance of an incident, rather than trying to carry them out in the chaotic time directly after the problem has occurred. We also need to review the privacy setting on all our accounts. Many times we can minimize the data that would be exposed or tailor it so that the information used would alter us to which account was compromised. Finally we need to have polices about what information about the organization can be shared. Should employees be allowed to take pictures at work and share them online?

Operations security in the real world

As we have discussed throughout the chapter, we can see the concepts of operations security at work in many areas. In government, we can see the formalized use of OPSEC as a mandate. Clearly, when we are dealing with information pertaining to conducting wars and military actions, weapons systems of great power, political maneuvering, and other similar activities, protecting such items of information is critical and may result in the loss of many lives if we fail to do so.

In the business world, we may see the same operations security principles at work, but we may also see a large amount of variance in the way they are implemented. Depending on the industry in which we are conducting business and the types of information we are handling, we may see more or less of an operations security focus. In some cases, such as when our business is handling medical, financial, or educational information, for instance, we may fall under regulatory or contractual controls that require us to put certain protections in place. In these instances, we are much more likely to see the concepts of operations security applied with some level of rigidity. Otherwise, businesses may or may not choose to apply such ideas as they see fit.

In our personal lives, we may also choose to apply the principles of operations security, although often in a much more informal manner. Although we may not necessarily have nuclear secrets or databases full of personal information to protect, we still have quite a few items that might be considered critical information. We need to protect our financial information, data concerning our identity, personal records, or other items we might not want to be made public. In such cases, we may often shortcut the operations security process to simply identifying and finding ways to protect our personal information, but we are still going through the same general steps.

Summary

The history of operational security stretches far back into recorded history. We can find such principles espoused in the writings of Sun Tzu in the sixth century BC, in the words of George Washington, in writings from the business community, and in formal methodologies from the US government. Although the formalized ideas of operations security are a much more recent creation, the principles on which they are founded are ancient indeed but still just as useful as the day they were developed.

The operations security process consists of five major steps. We start by identifying our most critical information so that we know what we need to protect. We then analyze our situation in order to determine what threats we might face, and following that what vulnerabilities exist in our environment. Once we know what threats and vulnerabilities we face, we can attempt to determine what risks we might face. The actual risks that are present are a combination of matching threats and vulnerabilities. When we know what risks we face, we can then plan out the countermeasures we might put in place in order to mitigate our risks.

As somewhat of a summarization of the operations security process, we can also look to the Laws of OPSEC, as penned by Kurt Haas. “If you don’t know the threat, how do you know what to protect?” “If you don’t know what to protect, how do you know you are protecting it?” “If you are not protecting it (the information), … THE DRAGON WINS!” [5]. These three laws cover some of the high points of the process and point out some of the more important aspects we might want to internalize.

In addition to the use of the operations security principles in business and in government, we also make use of such security concepts in our personal lives, even though we may not do so in a formal manner. We often take the steps of identifying our critical information and planning out measures to protect it in the normal course of our lives. Particularly with the sheer volume of our personal information that moves through a variety of systems and networks, it becomes increasingly important for us to take steps to protect it.

Exercises

1. Why is it important to identify our critical information?

2. What is the first law of OPSEC?

3. What is the function of the IOSS?

4. What part did George Washington play in the origination of operations security?

5. In the operations security process, what is the difference between assessing threats and assessing vulnerabilities?

6. Why might we want to use information classification?

7. When we have cycled through the entire operations security process, are we finished?

8. From where did the first formal OPSEC methodology arise?