Chapter 1. Introduction

Now more than ever, organizations are increasingly becoming acquirers1 of needed capabilities by obtaining products and services from suppliers and developing less and less of these capabilities in-house. This widely adopted business strategy is designed to improve an organization’s operational efficiencies by leveraging suppliers’ capabilities to deliver quality solutions rapidly, at lower cost, and with the most appropriate technology.

Authors’ Note

A May 2010 report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that only 21 percent of programs in the U.S. Department of Defense’s 2008 major defense acquisition portfolio appeared to be stable and on track with original cost and schedule goals [GAO: Defense Acquisition, 2010].

Acquisition of needed capabilities is challenging because acquirers have overall accountability for satisfying the end user while allowing the supplier to perform the tasks necessary to develop and provide the solution.

Mismanagement, the inability to articulate customer needs, poor requirements definition, inadequate supplier selection and contracting processes, insufficient technology selection procedures, and uncontrolled requirements changes are factors that contribute to project failure. Responsibility is shared by both the supplier and the acquirer. The majority of project failures could be avoided if the acquirer learned how to properly prepare for, engage with, and manage suppliers.

General Motors Information Technology is a leader in working with its suppliers. See Chapter 6 for an essay about GM’s use of CMMI-ACQ to learn more about how sophisticated the relationships and communication with suppliers can be.

In addition to these challenges, an overall key to a successful acquirer–supplier relationship is communication.

Unfortunately, many organizations have not invested in the capabilities necessary to effectively manage projects in an acquisition environment. Too often acquirers disengage from the project once the supplier is hired. Too late they discover that the project is not on schedule, deadlines will not be met, the technology selected is not viable, and the project has failed.

The acquirer has a focused set of major objectives. These objectives include the requirement to maintain a relationship with end users to fully comprehend their needs. The acquirer owns the project, executes overall project management, and is accountable for delivering the product or service to the end users. Thus, these acquirer responsibilities can extend beyond ensuring the product or service is delivered by chosen suppliers to include activities such as integrating the overall product or service, ensuring it makes the transition into operation, and obtaining insight into its appropriateness and adequacy to continue to meet customer needs.

CMMI for Acquisition (CMMI-ACQ) enables organizations to avoid or eliminate barriers in the acquisition process through practices and terminology that transcend the interests of individual departments or groups.

Authors’ Note

If the acquirer and its suppliers are both using CMMI, they have a common language they can use to enhance their relationship.

CMMI-ACQ contains 22 process areas. Of those process areas, 16 are core process areas that cover Process Management, Project Management, and Support process areas.2

The CMF concept is what enables CMMI to be integrated for both supplier and acquirer use. The shared content across models for different domains enables organizations in different domains (e.g., acquirers and suppliers) to work together more effectively. It also enables large organizations to use multiple CMMI models without making a huge investment in learning new terminology, concepts, and procedures.

Six process areas focus on practices specific to acquisition, addressing agreement management, acquisition requirements development, acquisition technical management, acquisition validation, acquisition verification, and solicitation and supplier agreement development.

All CMMI-ACQ model practices focus on the activities of the acquirer. Those activities include supplier sourcing; developing and awarding supplier agreements; and managing the acquisition of capabilities, including the acquisition of both products and services. Supplier activities are not addressed in this document. Suppliers and acquirers who also develop products and services should consider using the CMMI-DEV model.

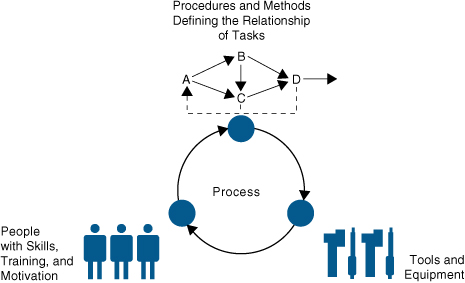

About Process Improvement

In its research to help organizations to develop and maintain quality products and services, the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) has found several dimensions that an organization can focus on to improve its business. Figure 1.1 illustrates the three critical dimensions that organizations typically focus on: people, procedures and methods, and tools and equipment.

Figure 1.1 The Three Critical Dimensions

What holds everything together? It is the processes used in your organization. Processes allow you to align the way you do business. They allow you to address scalability and provide a way to incorporate knowledge of how to do things better. Processes allow you to leverage your resources and to examine business trends.

Authors’ Note

Another advantage of using CMMI models for improvement is that they are extremely flexible. CMMI doesn’t dictate which processes to use, which tools to buy, or who should perform particular processes. Instead, CMMI provides a framework of flexible best practices that can be applied to meet the organization’s business objectives no matter what they are.

This is not to say that people and technology are not important. We are living in a world where technology is changing at an incredible speed. Similarly, people typically work for many companies throughout their careers. We live in a dynamic world. A focus on process provides the infrastructure and stability necessary to deal with an ever-changing world and to maximize the productivity of people and the use of technology to be competitive.

Manufacturing has long recognized the importance of process effectiveness and efficiency. Today, many organizations in manufacturing and service industries recognize the importance of quality processes. Process helps an organization’s workforce to meet business objectives by helping them to work smarter, not harder, and with improved consistency. Effective processes also provide a vehicle for introducing and using new technology in a way that best meets the business objectives of the organization.

About Capability Maturity Models

A Capability Maturity Model (CMM), including CMMI, is a simplified representation of the world. CMMs contain the essential elements of effective processes. These elements are based on the concepts developed by Crosby, Deming, Juran, and Humphrey.

In the 1930s, Walter Shewhart began work in process improvement with his principles of statistical quality control [Shewhart 1931]. These principles were refined by W. Edwards Deming [Deming 1986], Phillip Crosby [Crosby 1979], and Joseph Juran [Juran 1988]. Watts Humphrey, Ron Radice, and others extended these principles further and began applying them to software in their work at IBM (International Business Machines) and the SEI [Humphrey 1989]. Humphrey’s book, Managing the Software Process, provides a description of the basic principles and concepts on which many of the Capability Maturity Models (CMMs) are based.

The SEI has taken the process management premise, “the quality of a system or product is highly influenced by the quality of the process used to develop and maintain it,” and defined CMMs that embody this premise. The belief in this premise is seen worldwide in quality movements, as evidenced by the International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission (ISO/IEC) body of standards.

CMMs focus on improving processes in an organization. They contain the essential elements of effective processes for one or more disciplines and describe an evolutionary improvement path from ad hoc, immature processes to disciplined, mature processes with improved quality and effectiveness.

Like other CMMs, CMMI models provide guidance to use when developing processes. CMMI models are not processes or process descriptions. The actual processes used in an organization depend on many factors, including application domains and organization structure and size. In particular, the process areas of a CMMI model typically do not map one to one with the processes used in your organization.

The SEI created the first CMM designed for software organizations and published it in a book, The Capability Maturity Model: Guidelines for Improving the Software Process [SEI 1995].

Today, CMMI is an application of the principles introduced almost a century ago to this never-ending cycle of process improvement. The value of this process improvement approach has been confirmed over time. Organizations have experienced increased productivity and quality, improved cycle time, and more accurate and predictable schedules and budgets [Gibson 2006].

Evolution of CMMI

The CMM Integration project was formed to sort out the problem of using multiple CMMs. The combination of selected models into a single improvement framework was intended for use by organizations in their pursuit of enterprise-wide process improvement.

Developing a set of integrated models involved more than simply combining existing model materials. Using processes that promote consensus, the CMMI Product Team built a framework that accommodates multiple constellations.

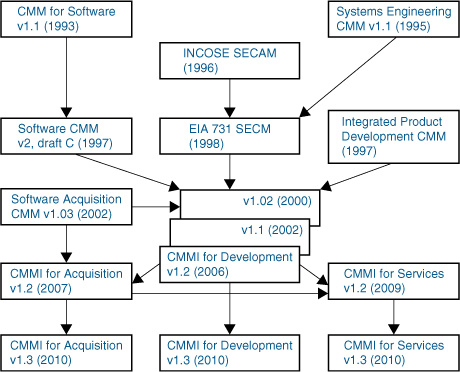

The first model to be developed was the CMMI for Development model (then simply called “CMMI”). Figure 1.2 illustrates the models that led to CMMI Version 1.3.

Figure 1.2 The History of CMMs3

Initially, CMMI was one model that combined three source models: the Capability Maturity Model for Software (SW-CMM) v2.0 draft C, the Systems Engineering Capability Model (SECM) [EIA 2002], and the Integrated Product Development Capability Maturity Model (IPD-CMM) v0.98.

These three source models were selected because of their successful adoption or promising approach to improving processes in an organization.

Every CMMI model must be used within the framework of the organization’s business objectives. An organization’s processes should not be restructured to match a CMMI model’s structure.

The first CMMI model (V1.02) was designed for use by development organizations in their pursuit of enterprise-wide process improvement. It was released in 2000. Two years later version 1.1 was released and four years after that, version 1.2 was released.

By the time that version 1.2 was released, two other CMMI models were being planned. Because of this planned expansion, the name of the first CMMI model had to change to become CMMI for Development and the concept of constellations was created.

The CMMI for Acquisition model was released in 2007 [SEI 2007a]. Since it built on the CMMI for Development Version 1.2 model, it also was named Version 1.2. Two years later the CMMI for Services model was released. It built on the other two models and also was named Version 1.2.

Authors’ Note

The Acquisition Module was updated after CMMI-ACQ was released. Now called the CMMI for Acquisition Primer, Version 1.2, it continues to be an introduction to CMMI-based improvement for acquisition organizations. The primer is an SEI report (CMU/SEI-2008-TR-010) that you can find at www.sei.cmu.edu/library/reportspapers.cfm.

In 2008 plans were drawn to begin developing Version 1.3, which would ensure consistency among all three models and improve high maturity material. Version 1.3 of CMMI for Acquisition [Gallagher 2011], CMMI for Development [Chrissis 2011, SEI 2010a], and CMMI for Services [Forrester 2011, SEI 2010b] were released in November 2010.

CMMI Framework

The CMMI Framework provides the structure needed to produce CMMI models, training, and appraisal components. To allow the use of multiple models within the CMMI Framework, model components are classified as either common to all CMMI models or applicable to a specific model. The common material is called the “CMMI Model Foundation” or “CMF.”

The components of the CMF are part of every model generated from the CMMI Framework. Those components are combined with material applicable to an area of interest (e.g., acquisition, development, services) to produce a model.

A “constellation” is defined as a collection of CMMI components that are used to construct models, training materials, and appraisal related documents for an area of interest (e.g., acquisition, development, services). The Acquisition constellation’s model is called “CMMI for Acquisition” or “CMMI-ACQ.”

CMMI for Acquisition

The CMMI Steering Group initially approved a small introductory collection of acquisition best practices called the Acquisition Module (CMMI-AM), which was based on the CMMI Framework. While it described best practices, it was not intended to become an appraisable model nor a model suitable for process improvement purposes. A similar, but more up-to-date document, CMMI for Acquisition Primer, is now available [Richter 2008].

General Motors partnered with the SEI to create the initial Acquisition model draft that was the basis for this model. The model now represents the work of many organizations and individuals from industry, government, and the SEI.

When using this model, use professional judgment and common sense to interpret it for your organization. That is, although the process areas described in this model depict behaviors considered best practices for most acquirers, all process areas and practices should be interpreted using an in-depth knowledge of CMMI-ACQ, your organizational constraints, and your business environment [SEI 2007b].

This document is a reference model that covers the acquisition of needed capabilities. Capabilities are acquired in many industries, including aerospace, banking, computer hardware, software, defense, automobile manufacturing, and telecommunications. All of these industries can use CMMI-ACQ.