6. Managing the Legal Risks of User-Generated Content

UGC can be a key driver of website traffic, thereby increasing the site’s value and its organic search engine page rank. Because this type of content is regularly updated, it is an instrumental ingredient for search engine optimization (SEO) purposes. UGC also serves as an effective and influential means to capture leads, and increase website conversion rates and sales based on positive reviews, testimonials, and endorsements.

Despite these benefits, however, UCG should not be viewed only as a corporate asset. The use of UGC also presents a number of legal challenges concerning potential copyright infringement, defamation, invasion of privacy, and the like which makes it a significant source of potential liability as well. Whenever UGC is involved, businesses need to remain vigilant against hosting content that is defamatory (against a person or another business, employee, competitor, or vendor), offensive, pornographic, racist, sexist, or otherwise discriminatory, or that infringes another’s IP or privacy rights.

Fortunately, important legal safeguards exist which serve to shield businesses hosting impermissible UGC from such potential liability. This chapter examines these safeguards, in particular, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), and the Communications Decency Act (CDA). Generally speaking, the DMCA protects website operators against claims of copyright infringement associated with UCG it hosts; and the CDA protects website operators from claims of defamation and invasion of privacy rights arising from UGC hosted on their sites.

To enjoy the protections offered by the DMCA and CDA, however, businesses are required to fully comply with a very detailed set of legal requirements, leaving little room for error. Because the law imposes an extremely high level of detail upon businesses seeking DMCA and CDA “safe harbor” protection, the descriptions contained in this chapter are necessarily highly detailed as well. Strict compliance with these requirements (albeit, exacting) nevertheless should allow businesses harnessing UGC to do so without losing their statutory immunity.

Copyright in the Age of Social Media

Because social media sites are not exempt from traditional copyright laws, copyright infringement is unquestionably the greatest intellectual property (IP) legal issue facing UGC providers. Even uploading another’s picture onto the company’s Facebook page without the author’s consent might violate the author’s copyright. To avoid civil and criminal law sanctions for copyright infringement, care should be taken to ensure that all necessary rights for publication on social networking sites have been properly assigned and that any uploaded content is noninfringing of another’s copyright.

![]() Note

Note

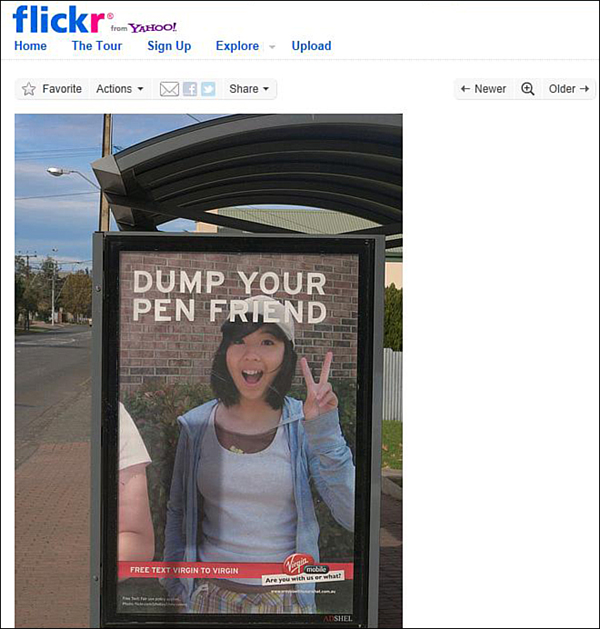

Australia’s Virgin Mobile phone company’s recent high-profile dispute regarding its alleged misuse of UGC is a helpful reminder that companies should obtain permission from all relevant parties before using another’s photo (or other UGC), including the subjects depicted in the photo as well as its author. In that case, Virgin Mobile—as part of its “Are You With Us Or What?” marketing campaign to promote free text messaging and other services—allegedly grabbed a picture of teenager Alison Chang from Flickr (a popular photo-sharing website), and plastered her photo on billboards throughout Australia without her consent. (See Figure 6.1.) In the ad, Virgin Mobile printed one of its campaign slogans, “Dump your pen friend,” over Alison’s picture. Further, to 16-year-old Chang’s great embarrassment, at the bottom of the ad was also printed “Free text virgin to virgin.” Chang (through her mother since Chang was a minor) filed suit against Virgin Mobile in the U.S., alleging invasion of privacy (misappropriating her name and likeness without her consent) and libel (false statements subjecting her to public humiliation).1 The photographer, Justin Ho-Wee Wong, also a plaintiff in the suit, brought an action for, among other matters, copyright infringement and breach of contract for Virgin Mobile’s alleged failure to properly attribute him as the photographer.

Figure 6.1 Virgin Mobile ad using another’s photo and likeness allegedly without permission. (Original photo by Justin Ho-Wee Wong from his Flickr photo-sharing web page.)

Although the case is still pending (and no final decision has yet been reached), Virgin Mobile serves as a helpful lesson to other businesses using UGC to be sure to have all necessary permissions in place before such content is used.

Copyright infringement is traditionally divided into three categories: direct infringement, contributory infringement, and vicarious infringement.

Direct Infringement

In a claim for direct copyright infringement,2 the injured party must show that it owns the copyright in the work and that the defendant violated one or more of the plaintiff’s exclusive rights under the Copyright Act,3 including the rights to:

• Reproduce the copyrighted work4

• Prepare derivative works based on the copyrighted work5

• Distribute copies of the copyrighted work6

• Publicly perform copyrighted literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and motion pictures and other audiovisual works7

• Publicly display copyrighted literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work8

• Publicly perform copyrighted sound recordings by means of a digital audio transmission9

A company may be liable for direct infringement whenever it uses a copyrighted work of another without permission. While such conduct may appear innocuous, uploading another’s song or photo onto your site—even those found on the web “for free”—without permission are examples of direct copyright infringement.

Contributory Infringement

To prevail under a claim of contributory copyright infringement, a plaintiff must show that the defendant (a) has knowledge of the infringing activity; and (b) induces, encourages, or materially contributes to the infringing conduct of the direct infringer.10

In other words, just as selling burglary tools to a burglar may expose you to liability, if you provide the means (for example, software) that allows users to share copyrighted works with the objective of promoting infringement, you may be held “contributorily” liable for the direct infringement of those third parties.

Vicarious Infringement

Finally, in the case of vicarious copyright infringement, the defendant may be held liable for another’s direct infringement if the defendant (a) had the right and ability to monitor and control the direct infringer; and (b) profits from the infringing activity.11

By way of example, the operator of a flea market in which counterfeit recordings were regularly sold was found to be a vicarious infringer because he could have monitored the vendors who rented booths from him (but failed to do so). Also, the flea market operator made money from that booth rental as well as from admission and parking fees from the flea market attendees (many of whom paid such fees in order to gain access to the counterfeit recordings).12

Digital Millennium Copyright Act

Hosting infringing copyrighted content can create liability for contributory or vicarious infringement, as noted above. To avoid liability, online companies that enable their users to upload content must strictly comply with the federal Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA),13 which provides a safe harbor (that is protection and immunity) for online service providers against claims of any alleged copyright infringement committed by their users.

The DMCA, signed into law on October 28, 1998, was passed to address the growing threat of digital copyright infringement. It criminalizes the production and dissemination of technology designed to circumvent measures that control access to copyrighted works, while simultaneously shielding service providers from liability for copyright infringement by their users. According to President Bill Clinton, who signed the bill into law, the DMCA “grant[s] writers, artists, and other creators of copyrighted material global protection from piracy in the digital age.”14

Title II of the DMCA (known as the Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act) generally protects online “service providers,”15 which include all website owners, from all monetary damages and most injunctive and other equitable relief for copyright infringement where a third party initiated the delivery of the allegedly infringing content and the service provider did not modify or selectively disseminate the content.

![]() Note

Note

The DMCA protects from liability the owners of Internet services, not the users (including marketers) who access them. Marketers utilizing UGC are not shielded under the DMCA with respect to uploading onto a third-party’s website copyright-infringing content.

As a general rule, to qualify for DMCA’s safe harbor protection, online service providers (OSPs) that store content uploaded by users must, among other things:

• Adopt (and reasonably implement) a policy of terminating the accounts of subscribers who repeatly infringe copyrights of others

• Designate an agent registered with the U.S. Copyright Office to receive notifications of claimed copyright infringement

• Expeditiously remove or block access to the allegedly infringing content upon receiving notice of the alleged infringement

• Not receive a financial benefit directly attributable to the infringing activity, in a case in which the service provider has the right and ability to control such activity

• Not have actual knowledge of the infringement, not be aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent (the so-called red flag test16), or upon gaining such knowledge or awareness, respond expeditiously to take the material down or block access to it17

Are DMCA’s requirements of direct financial benefit and the red flag test anachronistic in light of the present-day proliferation of social media sites whose raison d’être is UGC? In A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc.,18 the court held that copyrighted material on Napster’s site created a “draw” for customers that resulted in a “direct financial benefit” because Napster’s future revenue was “directly dependent” on the size and increase in its user base. Indeed, Napster’s primary purpose was to facilitate the distribution of copyrighted media files (primarily music) across a network of millions of users.

By contrast, in Ellison v. Robertson,19 the court held that AOL did not receive a “direct financial benefit” when a user stored infringing material on its server because the copyrighted work did not “draw” new customers. AOL neither “attracted [nor] retained ... [nor] lost ... subscriptions” because of the infringing material; instead, AOL’s service (which allowed users to store messages from various online discussion groups, including the alleged infringing message) was simply an “added benefit” to customers. For social media sites hosting UGC, the exact contours of what constitutes drawing in new customers to receive a direct financial benefit will have to be elucidated on a case-by-case basis.

To qualify for the protection against liability for taking down material, the online service provider must promptly notify the subscriber that it has removed or disabled access to the material and provide the subscriber with the opportunity to respond to the notice and takedown by filing a counter notification.20 If the subscriber serves a counter notification complying with the DCMA’s statutory requirements, including a statement under penalty of perjury that the subscriber believes in good faith that the material was removed or disabled through mistake or misidentification, then unless the copyright owner files an action seeking a court order against the subscriber, the service provider must put the material back up within 10 to 14 business days after receiving the counter notification.21 Penalties are provided for knowingly making material misrepresentations in either a notice or a counternotice. Any person who knowingly materially misrepresents that the challenged content is infringing, or that it was removed or disabled through mistake or misidentification, is liable for any resulting damages (including costs and attorneys’ fees) incurred by the alleged infringer, the copyright owner or its licensee, or the service provider.22

Copyright holders must also consider fair use23 (that is, statutorily permitted use of a copyrighted work in a non-infringing manner) before issuing DMCA takedown notices for allegedly infringing content posted on the Internet. Whether a particular use of copyrighted materials constitutes fair use depends upon the following factors:

• The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes

• The nature of the copyrighted work

• The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole

• The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

For example, in Lenz v. Universal Music Corp.,24 the plaintiff posted on YouTube a home video of her children dancing to Prince’s song “Let’s Go Crazy.” Universal Music Corporation (Universal) sent YouTube a DMCA takedown notice alleging that plaintiff’s video violated its copyright in the song. Lenz (the plaintiff) claimed fair use of the copyrighted material and sued Universal for misrepresentation of its DMCA claim. In denying Universal’s motion to dismiss, the court held that Universal had not in good faith considered fair use when filing a takedown notice and that the plaintiff was therefore entitled to monetary damages.

The case of UMG Recordings, Inc. v. Veoh Networks, Inc.25 provides additional guidance to OSPs seeking insulation under the “safe harbor” provisions of the DMCA. In this case, UMG, one of the world’s largest record labels (including Motown and Def Jam) and music publishing companies, sued Veoh, an operator of a video sharing website, for direct and contributory copyright infringement. Despite the various procedures implemented by Veoh on its website to prevent copyright infringement (including third-party filtering solutions), Veoh’s users were still able to make numerous unauthorized downloads of songs for which UMG owned the copyright. UMG claimed, however, that Veoh’s actions were insufficient due to Veoh’s late adoption of the filtering technology to detect infringing material and because Veoh removed only the specific videos identified in DMCA takedown notices, but not other infringing material that the filter detected.

In affirming the lower’s court dismissal of the case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit found that Veoh was entitled to protection under the DMCA’s safe harbor for the following reasons:

• Veoh did not have actual knowledge of the infringing activity. “[M]erely hosting a category of copyrightable content ... with the general knowledge that one’s services could be used to share infringing material, is insufficient to meet the actual knowledge requirement.” To hold otherwise would render the safe harbor provisions “a dead letter.” Rather, “specific knowledge of particular infringing activity” is required for an OSP to be rendered ineligible for safe harbor protection.

• Veoh did not have the right and ability to control infringing activity (which would otherwise disqualify it for safe harbor protection). “[T]he ‘right and ability to control’ ... requires control over specific infringing activity the provider knows about” and “a service provider’s general right and ability to remove materials from its services is alone insufficient.” Here, Veoh only had the necessary right and ability to control infringing activity once it had been notified of such activity. It would be a “practical impossibility for Veoh to ensure that no infringing material is ever uploaded to its site, or to remove unauthorized material that has not yet been identified to Veoh as infringing.”

• Veoh did not lose DMCA safe harbor protection because it did more than merely store uploaded content. For example, it automatically converted the videos into smaller “chunks” and “transcoded” the video into a format that would make the videos more easily accessible to other users. The DMCA’s safe-harbor provisions are not limited only to web host services (versus the web services themselves). Rather, such provisions also “encompass the access-facilitating processes that automatically occur when a user uploads a video.” “Veoh has simply established a system whereby software automatically processes user-submitted content and recasts it in a format that is readily accessible to its users.” Veoh does not actively participate in or supervise file uploading, “[n]or does it preview or select the files before the upload is completed.”

• Veoh did not receive a financial benefit directly attributable to the infringing activity (which would otherwise render it ineligible for safe harbor protection). Rather, Veoh took down infringing material as soon as it was notified of the infringement.

Interestingly, even though UMG presented evidence of emails sent to Veoh executives and investors by copyright holders regarding infringing activity—including one sent by the CEO of Disney to Michael Eisner, a Veoh investor, representing that the movie Cinderalla III and certain episodes from the television series Lost were available on Veoh without Disney’s permission—the Ninth Circuit Appeals Court held that this was insufficient to create actual knowledge of infringement on Veoh’s part (and therefore an obligation to remove infringing content). Rather, Disney, as an alleged infringed copyright holder, was subject to the DMCA’s notification requirements, which these informal emails failed to meet. In any event, Veoh reportedly removed this offending material immediately upon learning of it.

As the Ninth Circuit’s decision in UMG Recordings makes clear, when statutorily compliant and specific DMCA takedown notices are received, a website operator or service provider should act swiftly to remove the specifically identified infringing content. Such prompt action should help shield website operators and service providers from liability under the DMCA’s safe harbor provisions that would otherwise arise from hosting infringing UGC.

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

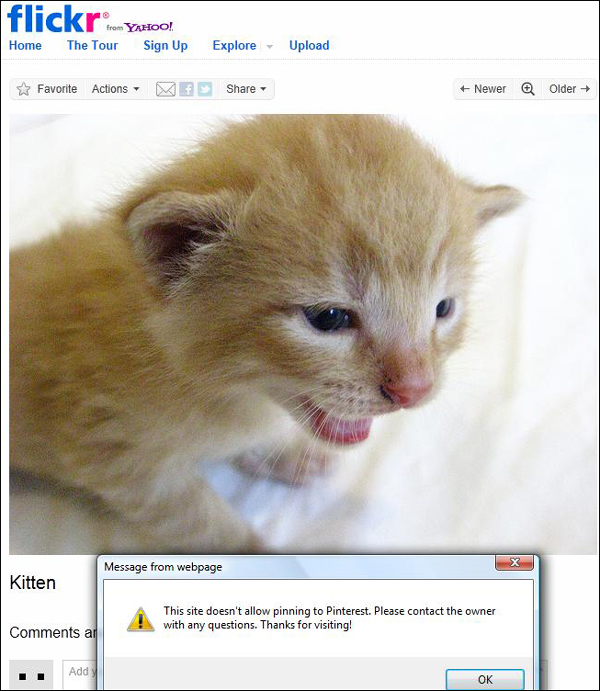

Social media site Pinterest, which enables users to “pin” interesting photos to a virtual pinboard to share with others (such as clothing, jewelry, honeymoon destinations, “yummy desserts,” and anything else that strikes a person’s fancy), has become the focus of mounting concern that the site encourages unauthorized sharing of copyrighted materials. To help allay such fears, Pinterest is allowing website owners (and copyright holders) to opt-out of being featured on the site, by adding a “nopin” meta tag to their site. Pinterest users attempting to share images or other material from a site with the “nopin” code will be presented with the following message (also shown in Figure 6.2):

Figure 6.2 Even photos of cute kittens are copyright protected. Attempting to “pin” this photo displayed on Flickr resulted in a warning message.

“This site doesn’t allow pinning to Pinterest. Please contact the owner with any questions. Thanks for visiting!”

Further, Pinterest’s Terms of Use includes a provision requiring its members to indemnify (read: pay or reimburse) Pinterest for any monetary loss in the event infringing copyrighted material is “pinned:” ”You agree to defend, indemnify, and hold [Pinterest], its officers, directors, employees and agents, harmless from and against any claims, liabilities, damages, losses, and expenses, including, without limitation, reasonable legal and accounting fees, arising out of or in any way connected with (i) your access to or use of the Site, Application, Services or Site Content, (ii) your Member Content, or (iii) your violation of these Terms.”

Whether Pinterest’s “nopin” code will be sufficient to shield it from liability—leaving its members holding the bag for any infringing content they upload—remains to be seen.

Defamation, Invasion of Privacy, and CDA Immunity

Although likely the most costly, copyright issues are not the only legal concerns related to UGC. The posting of allegedly defamatory materials has also given rise to a series of lawsuits against UGC service providers. In Carafano v. Metrosplash.com, Inc.,26 for example, the plaintiff sued an Internet-based dating service (Matchmaker.com) for allegedly false content contained in her dating profile. According to the plaintiff (a popular actress who goes by the stage name Chase Masterso and who had a prominent recurring role in the TV show Star Trek: Deep Space Nine), the profile was posted by an imposter and contained a number of false statements about her, which characterized her as licentious. The case was ultimately dismissed based on immunity provided by the Communications Decency Act.

The federal Communications Decency Act of 1996 (CDA)27 immunizes website operators and other interactive computer service providers from liability for third parties’ tortious (legally wrongful) acts, including defamation, invasion of privacy, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. Section 230 of the CDA shields providers and users of interactive computer services from responsibility for third-party content. The CDA was specifically passed to help “promote the continued development of the Internet and other interactive computer services and other interactive media” and “to preserve the vibrant and competitive free market that presently exists for the Internet and other interactive computer services, unfettered by Federal or State regulation.”28

Section 230(c)(1) of the CDA states that “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”29 The statute further provides that “no cause of action may be brought and no liability may be imposed under any State or local law that is inconsistent with this section.”30 Accordingly, the provider, so long as not participating in the creation or development of the content, will be immune from defamation and other, nonintellectual property,31 state law claims arising from third-party content.

![]() Note

Note

Courts have broadly interpreted the term interactive computer service provider under the CDA to cover a wide range of web services, including online auction websites, online dating websites, operators of Internet bulletin boards, and online bookstore websites.32 At least one court has held that corporate employers that provide their employees with Internet access through the company’s internal computer systems are also among the class of parties potentially immune under the CDA.33

The potential breadth of CDA immunity can appear quite staggering. For example, in Doe II v. MySpace, Inc.,34 plaintiffs, young girls aged 13 to 15, were sexually assaulted by adults they met through the defendant’s Internet social networking site, MySpace. Through their parents or guardians, the plaintiffs brought four separate cases against the site, asserting claims for negligence. Underscoring the breadth of CDA immunity, the California Court of Appeals affirmed the lower court’s finding, holding that MySpace was not liable for what third parties posted on its site:

It has been long held that lawsuits seeking to hold service providers liable for the exercise of a publisher’s traditional editorial functions (such as deciding whether to publish, withdraw, postpone, or alter content) are generally barred.35 The 2010 to 2011 class-action lawsuit against consumer review site Yelp! Inc. further highlights the scope of the protection afforded interactive service providers under the CDA. In Levitt v. Yelp! Inc.,36 the defendant was accused of manipulating its consumer reviews to extort the plaintiff businesses to purchase advertising on its site. In particular, the plaintiffs alleged that Yelp relocated or removed positive reviews from its site, resulting in a lowered overall “star” rating for a business (whereas businesses purchasing advertising on Yelp were given prominent ratings); that it retained negative reviews, even if those reviews violated Yelp’s terms of service; and that employees of Yelp said they would manipulate reviews favorably for businesses that paid for advertising on the site.

Despite these allegations, the complaint against Yelp was dismissed because decisions to remove or reorder user content traditionally fall within the scope of Section 230 CDA immunity. According to the court, this is true even if Yelp had an improper motive in including certain reviews and excluding others. As to the policy of protecting possible bad faith exercises of editorial functions, the court observed:

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

The Internet is awash with message boards, review sites, and customer feedback forums that provide a public platform to bad-mouth a company and its employees behind a cloak of anonymity. Based on a single defamatory comment, a company’s good will, customer relations, and profits can be seriously affected. Companies that are harmed in this way should not despair, however, as there are means to ferret out the defamer’s identity. A “John Doe suit,” for example, allows a company to name the website or internet service provider as defendants (together with the fictitiously-named “John Doe”), and to compel them to turn over the identity of the offending online speaker.

While there is no universal standard for discovery of anonymous Internet users’ real identities, courts generally consider the following factors (or a permutation thereof) in assessing whether the companies’ need for compelled disclosure outweighs the online poster’s First Amendment right to anonymous speech:38

• Whether the plaintiff has sufficiently stated a cause of action for defamation

• Whether the discovery request is sufficiently specific to lead to identifying information

• Whether there are alternative means to obtain the subpoenaed information

• Whether there is a central need for the subpoenaed information to advance the claim

• Whether the anonymous Internet user has a reasonable expectation of privacy.39

Of course, learning the identity of the anonymous poster is one thing (for example, a rival company, an ex-employee); getting the website to take down the offending content is something else altogether. The latter potential remedy is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 8.

Limitations of CDA Immunity

Despite its broad breadth, CDA immunity does not attach (apply) if the host exercises editorial control over the content and the edits materially alter the meaning of the content. For companies that operate their own blogs, bulletin boards, YouTube channels, or other social media platforms, therefore, it is imperative that they avoid contributing to the “creation or development”40 of the offensive content so that their immunity is not revoked.

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

Does re-tweeting impermissible (say, defamatory) content fall within the grant of CDA immunity? Probably yes, because CDA immunity depends on the source of the information in the injurious statement, not the source of the statement itself, and the CDA protects both the provider and user of an interactive computer service. Reposting (or re-tweeting) such statements is most likely protected under the statute, provided the person reposting/re-tweeting did not actually take part in creating the original content.

The line demarking where content host ends and content creator begins is often blurry. In 2006, the franchisor for the popular Subway restaurants filed a lawsuit against Quiznos related to two television commercials and an online contest that invited consumers to submit videos comparing the competitors’ sandwiches, demonstrating “why you think Quiznos is better.”41 Perhaps inevitably, various allegedly disparaging videos were submitted, including one wherein a Subway sandwich is portrayed as a submarine unable to dive because it does not have enough meat.

Despite the defendant’s Section 230 CDA immunity objections, the court declined to dismiss the case because an issue existed as to whether Quiznos merely published information provided by third parties or instead was “actively responsible for the creation and development of disparaging representations about Subway contained in the contestant videos.”42 According to the court:

![]() Note

Note

There are important comparative advertisement lessons to be taken away from this case as well. As discussed in greater detail in Chapter 7, businesses should take care that the statements made in their promotional messages are true, regardless of whether the statements are made in traditional or new media, and regardless of whether the statements are made directly by the business or by others on the business behalf, or which were created or developed with the businesses’ active participation.

The case of Fair Housing Council v. Roommates.com, LLC,44 is further illustrative of the fact that the immunity afforded by the CDA is not absolute and may be forfeited if the site owner invites the posting of illegal materials or makes actionable postings itself. The defendant operates a website to match people looking to share a place to live. As part of the registration process, subscribers had to create a profile that required them to answer a series of questions, including his/her sex, sexual orientation, and whether he/she would bring children to a household. The appellate court found that because the operator created the discriminatory questions and choice of answers and designed its online registration process around them, it was the “information content provider”45 as to the questions and could claim no CDA immunity for posting them on its website, or for forcing subscribers to answer them as a condition of accessing its services. By these actions, the defendant was found to be more than a passive transmitter of information provided by others; rather, it “created or developed,” at least in part, that information, and accordingly, lost its CDA immunity.

![]() Note

Note

A blog or chat room operator is not protected under CDA if it hosts content that infringes the intellectual property rights of others, including their trademarks and copyrights. In the latter case, to be shielded from liability, the operator must conform to the notice, take down, and other procedures of the DMCA, as detailed earlier in this chapter.

Further, the CDA carves out its own exception to its grant of statutory immunity. While under Section 230 of the CDA “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider” and “no cause of action may be brought and no liability may be imposed under any State or local law that is inconsistent with this section,” Section 230(e)(2)states that the CDA should not “be construed to limit or expand any law pertaining to intellectual property.” Accordingly, the CDA will not bar IP claims asserted against a site operator.

In Doe v. Friendfinder Network, Inc. et al.,46 for example, a federal district court in New Hampshire ruled that the CDA does not preclude a state law right of publicity claim against operators of a “sex and swinger” online community who reposted—as advertisements on other third-party websites—naked photos and a sexual profile “reasonably identified” as the plaintiff without the plaintiff’s knowledge or consent. The plaintiff brought eight claims against the defendants, including for defamation, invasion of privacy, and false designation in violation of Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act.47

The plaintiff’s invasion of privacy claim was predicated on four separate theories:

• The defendants intruded on the plaintiff’s solitude (by exposing intimate—albeit, non-factual—details of her life to the public)

• The defendants publicly disclosed private “facts” about the plaintiff

• The defendants cast the plaintiff in a false light (by implying, for example, that she was a “swinger” or engaged in a “promiscuous sexual lifestyle”)

• The defendants appropriated plaintiff’s identity for their own benefit.

According to the court, only the fourth theory (the right of publicity) was a widely recognized IP right exempt from CDA immunity. “The other three torts encompassed by the ‘right of privacy’ rubric, however, do not fit that description. Unlike a violation of the right to publicity, these causes of action—intrusion upon seclusion, publication of private facts, and casting in false light—protect ‘a personal right, peculiar to the individual whose privacy is invaded’ which cannot be transferred like other property interests.”48 In applying the CDA’s grant of immunity, therefore, the court allowed the defendant’s motion to dismiss the plaintiff’s state tort claims (defamation, invasion of privacy, and so on) but permitted her state and federal IP claims (violation of right to publicity and false designation) to proceed.

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

The CDA and DMCA safe harbor are not the only legal protections available to online hosts of UGC. As violations of a terms of service may constitute “exceeding authorized access” under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA),49 a terms of service explicitly prohibiting uploading or posting infringing or defamatory content, and a prominent click-wrap agreement requiring the user to read and actively accept the terms and conditions by clicking an I Accept button, for example (versus a terms of service accessible via a link), are also advisable. The terms of service should also require that all appropriate representations, warranties, and indemnities from users submitting UGC are given.

Although the use of UGC presents a number of legal issues concerning copyright infringement, defamation, and privacy rights violations, there are important legal protections available to businesses to immunize them from such claims. However, strict compliance with the DMCA and CDA’s statutory requirements is mandated if a business does not want to lose its statutory immunity. Figure 6.3 provides a summary of some of these key requirements, as well as other practical tips for businesses hosting UGC.

Figure 6.3 Social Media Legal Tips for Managing the Legal Risks of User-Generated Content.

Chapter 6 Endnotes

1 Chang et al. v. Virgin Mobile USA, LLC et al., Case No 3:07-CV-01767-D (N.D. Tex., Oct. 19, 2007). The action was dismissed without prejudice on jurisdictional grounds, as the challenged conduct allegedly occurred primarily in Australia. The case was subsequently refilled, and is currently pending in the U.S. District Court, California Northern District. See Chang et al. v. Virgin Mobile USA, LLC et al., Case No. 5:08-MC-80095-JW (N.D. Tex., May 8, 2008)

2 17 U.S.C. § 501(a)-(b)

3 17 U.S.C. §101 et seq.

4 17 U.S.C. § 106(1)

5 17 U.S.C. § 106(2)

6 17 U.S.C. § 106(3)

7 17 U.S.C. § 106(4)

8 17 U.S.C. § 106(5)

9 17 U.S.C. § 106(6)

10 See, for example, MGM Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913 (2005)

11 Id. at 930

12 Fonovisa Inc. v. Cherry Auction, 76 F.3d 259, 37 USPQ2d 1590 (9th Cir. 1996)

13 Pub. L. No. 105-304, 112 Stat. 2860 (Oct. 28, 1998)

14 Statement by the President on Digital Millennium Copyright, 1998 WL 754861 (Oct. 29, 1998)

15 As it relates to providing online transitory communications, service provider is defined in section 512(k)(1)(A) of the Copyright Act as “an entity offering the transmission, routing, or providing of connections for digital online communications, between or among points specified by a user, of material of the user’s choosing, without modification to the content of the material as sent or received.”

For purposes of service providers providing storage of information on websites (or other information repositories) at the direction of users, service provider is more broadly defined as “a provider of online services or network access, or the operator of facilities therefore.” Title 17 U.S.C., § 512(k)(l)(B)

16 According to the legislative history of § 512(c)(1)(A)(ii) of the DMCA, the red flag test (to determine whether an infringing activity is “apparent”) contains both a subjective and an objective element. The subjective element examines the OSP’s knowledge during the time it was hosting the infringing material. The objective element requires that the court examine all relevant facts to determine if a “reasonable person operating under the same or similar circumstances” would find that infringing activity was apparent See H.R. Rep. No. 105-551(II) at 53 (1998).

17 17 U.S.C., §§ 512(c) and 512(i)

18 A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc., 239 F.3d 1004 (9th Cir. 2001)

19 Ellison v. Robertson, 357 F.3d 1072 (9th Cir. 2004)

20 17 U.S.C. § 512(g)(2)

21 17 U.S.C. §§ 512(g)(2) and 512(g)(3)

22 17 U.S.C. § 512(f)

23 17 U.S.C. § 107

24 Lenz v. Universal Music Corp. et al, 572 F. Supp. 2d 1150 (N.D. Cal. 2008)

25 UMG Recordings, Inc., et al. v. Veoh Networks, Inc., Case No. 10-55732 (9th Cir., Dec. 20, 2011)

26 Carafano v. Metrosplash.com, Inc., 339 F.3d 1119 (9th Cir. 2003)

27 Public Law No. 104-104 (Feb. 8, 1996), codified at 47 U.S.C. §230

28 47 U.S.C. § 230(b)

29 47 U.S.C. § 230(f)(2) defines interactive computer service as “any information service, system, or access software provider that provides or enables computer access by multiple users to a computer server, including specifically a service or system that provides access to the Internet and such systems operated or services offered by libraries or educational institutions.”

Similarly, 47 U.S.C. § 230(f)(3) defines information content provider as “any person or entity that is responsible, in whole or in part, for the creation or development of information provided through the Internet or any other interactive computer service.”

30 47 U.S.C. § 230(e)(3)

31 47 U.S.C. § 230(e)(2) removes intellectual property law claims from the scope of immunity provided by the statute.

32 See, respectively, Gentry v. eBay, Inc., 99 Cal. App. 4th 816, 2002 Cal. App. LEXIS 4329; Carafano v. Metrosplash.com, Inc., 339 F.3d 1119 (9th Cir. 2003); Chicago Lawyers’ Comm. for Civil Rights Under the Law, Inc. v. Craigslist, Inc. (N.D.Ill. 2006) 461 F. Supp. 2d 681; and Schneider v. Amazon.com, Inc. 108 Wn. App. 454, 31 P.3d 37, 40–41] (2001)

33 Delfino v. Agilent Technologies, Inc., 145 Cal. App. 4th 790 (2006)

34 Doe II, a Minor, etc., et al., v. MySpace Incorporated, 175 Cal. App. 4th 561 (2009)

35 Zeran v. America Online, Inc., 129 F.3d 327, 330 (4th Cir. 1997)

36 Levitt et al., v. Yelp! Inc., Case No. 3:10-CV-01321-EMC (N.D. Cal. Mar. 29, 2010)

37 See Order Granting Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss (Chen, J.) (Oct. 26, 2011) in Levitt et al., v. Yelp! Inc., Case No. 3:10-cv-01321-EMC (N.D. Cal. Oct. 26, 2011) (Document 89) [Note: The case is currently on appeal.]

38 It is well-settled that the First Amendment’s protection extends to the Internet, even to anonymous speech. See, e.g., Reno v. ACLU, 521 U.S. 844, 870, 117 S.Ct. 2329 (1997) (“Through the use of chat rooms, any person with a phone line can become a town crier with a voice that resonates farther than it could from any soapbox.”); Doe v. 2TheMart.Com, Inc., 140 F.Supp.2d 1088, 1097 (W.D.Wash.2001) (“Internet anonymity facilitates the rich, diverse, and far ranging exchange of ideas ... [;] the constitutional rights of Internet users, including the First Amendment right to speak anonymously, must be carefully safeguarded.”).

39 See, e.g., Sony Music Entertainment Inc. v. Does 1-40, 326 F.Supp.2d 556 (S.D.NY 2004); and Columbia Insurance Company v. Seescandy.com, 185 F.R.D. 573 (N.D. Cal. 1999).

40 47 U.S.C § 230(f)(3) defines information content provider as “any person or entity that is responsible, in whole or in part, for the creation or development of information provided through the Internet or any other interactive computer service.”

41 Doctor’s Associates, Inc. v. QIP Holder LLC, et al., Case No. 3:06-CV-1710 (D. Conn.) (Oct. 27, 2006)

42 Doctor’s Associates, Inc. v. QIP Holder LLC, et al., Case No. 3:06-CV-1710 (D. Conn.) (Oct. 27, 2006) (Document 271) (order denying defendants’ motion for summary judgment entered Feb. 19, 2010)

43 Id.

44 Fair Housing Council v. Roommates.com, LLC, 521 F.3d 1157 (9th Cir. 2008) (en banc)

45 47 U.S.C. § 230(f)(3)

46 Doe v. Friendfinder Network, Inc. et al., 540 F.Supp.2d 288 (D.N.H. 2008)

47 See Section 43(a) of Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)

48 Doe v. Friendfinder Network, Inc. et al., 540 F.Supp.2d 288 (D.N.H. 2008) (internal citations omitted)

49 18 U.S.C. § 1030. See, in particular, § 1030(a)(4), which provides that “whoever knowingly and with intent to defraud, accesses a protected computer without authorization, or exceeds authorized access, and by means of such conduct furthers the intended fraud and obtains anything of value, unless the object of the fraud and the thing obtained consists only of the use of the computer and the value of such use is not more than $5,000 in any 1 year period ... shall be punished as provided in subsection (c) of this section.”