5. Social Media in Litigation and E-Discovery: Risks and Rewards

Social media presents unique challenges to businesses trying to manage their litigation risks. Indeed, an employee who responds to an online complaint regarding its company’s products—even without the company’s authorization—might be exposing (albeit, unwittingly) its employer to potential liability. If the employee posts something that is not accurate, for example, or that is otherwise inconsistent with the employer’s official stance, this may undermine the employer’s litigation position. What companies and their employees (even when not speaking in an official capacity) say online matters.

E-Discovery of Social Media

Users of social networks typically share personal information, pictures and videos, thereby creating a virtually limitless depository of potentially valuable, discoverable evidence for litigants.

Indeed, there is growing number of court cases where social media is playing a key role. For example:

• In Offenback v. LM Bowman, Inc. et al.,1 the plaintiff was ordered to turn over Facebook account information that contradicted his claim of personal injury; namely, despite claims that his motor vehicle accident prevented him from riding a motorcycle or being in traffic or around other vehicles, his Facebook postings showed that he continued to ride motorcycles, even on multistate trips.

• In EEOC v. Simply Storage Mgmt., LLC,2 a court in Indiana ordered the plaintiffs to produce social media postings, photographs, and videos “that reveal, refer, or relate to any emotion, feeling, or mental state” in a sexual harassment case where plaintiffs alleged severe emotional distress injuries, including post-traumatic distress disorder.

• In Largent v. Reed,3 a Pennsylvania court granted defendant’s motion to compel plaintiff to produce her Facebook username and password as her public Facebook profile included status updates about exercising at a gym and several photographs showing her enjoying life with her family that contradicted her claim of damages—that is, depression, leg spasms, and the need to use a cane.

• In Barnes v. CUS Nashville, LLC, 4, a magistrate judge in Tennessee created a Facebook account and requested that the witnesses accept the judge as a Facebook friend “for the sole purpose of reviewing photographs and related comments in camera” for discoverable materials relating to plaintiff’s personal injury claim.

The wealth of social media information has recently raised the issue of whether parties are entitled to discovery of an adversary’s social networking data, even when that data is designated as private.

Under federal and state laws governing procedures in civil courts, discovery is the pretrial phase in a lawsuit in which each party can obtain evidence from the opposing party (via requests for answers to interrogatories, requests for production of documents, requests for admissions, and depositions) and from nonparties (via depositions and subpoenas). Generally, a party can obtain discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any part’s claim or defense, or that is reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible evidence.5 Several courts have ruled that the content of social media is generally discoverable, despite privacy objections.6

![]() Note

Note

“Privileged” matters, such as confidential communications between an attorney and his/her client, or a doctor and his/her patient, are generally afforded special legal protection, such that the person holding the privilege (for example, the client or patient) may refuse to disclose, and prevent any other person from disclosing, any privileged communications. In most circumstances, given the relatively public nature of social media platforms, it’s not likely that any communications taking place thereon would be deemed “privileged.”

Under state and federal court rules, parties to a lawsuit are required to disclose (without awaiting a discovery request) a copy of all electronically stored information (ESI) that the disclosing party has in its possession, custody, or control and which it may use to support its claims or defenses.7 Businesses must take measures to preserve ESI not only at the inception of a lawsuit, but whenever litigation is reasonably anticipated (that is, the time before litigation when a party should have known that the evidence may be relevant to likely future litigation). In this regard, parties are required to initiate a litigation hold, halting the destruction of potentially relevant documents.

The duty to preserve ESI, therefore, might include requesting third-party providers, such as social media providers, to segregate and save relevant data. Whether the case involves a commercial dispute, employment litigation, or personal injury—postings, pictures and messages transmitted through social media sites can be a valuable source of discovery.

ESI generally presents more challenges in discovery and litigation holds than traditional hard-copy information, and the use of social media only increases those challenges. For example, given the inherently dynamic nature of social media, a risk exists that information held on a social media site may be changed or removed at any given moment for any number of reasons. Therefore, the legal hold requirement may mean downloading the information and retaining it in another format (such as a screen capture or PDF printout). Both Facebook and Twitter have procedures for the preservation and procurement of information from the sites, should a litigation hold be required. Care must be taken, however, to capture sufficient data so that it may be properly authenticated at trial and admitted into evidence.

Because discovery of social media communications can be used against a company in a lawsuit, employers should remind their employees that their postings might not be protected and that anything they say may be used against the company. Certainly, in the event of pending or anticipated litigation, employers should ensure that their employees do not post anything that might undermine the company’s legal position.

Employers should remind their employees that their postings might not be protected, and that anything they say may be used against the company.

Companies should also be mindful of the serious penalties that exist for certain failures to produce ESI. Is the loss of ESI due to a routine, good faith operation of an electronic system? If not, significant sanctions may be imposed for failure to produce ESI—including dismissal of your case, or a default judgment in favor of your opponent. A company’s retention policies, together with its routine destruction cycles, must be well documented to avoid the possible inference that any loss of ESI (including information placed on a company’s branded social networking sites) was the result of bad faith—such as the deliberate destruction, mutilation, alteration or concealment of evidence. In this regard, whenever litigation is reasonably anticipated, the destruction of a company’s ESI should be immediately suspended to avoid the negative inference.

While there do not appear to be any court decisions directly addressing the issue of whether a litigant can be sanctioned for failing to proactively preserve information on a social networking site, companies should consider sending their opponents a preservation letter specifically including such information and seek sanctions if they fail to abide. Because parties have control over what information is posted (and deleted) on their social media networking sites, court may be willing to consider sanctioning parties for failing to produce a copy of their communications on such sites.

In Katiroll Co. v. Kati Roll and Platters, Inc.,8 for example, a federal district court found that a spoliation inference was not appropriate—and sanctions were therefore not warranted—where a party changed his social media profile picture during the course of litigation as he had not been explicitly requested to preserve such evidence. This case involved a trademark infringement claim between two restaurants that sell a similar food called kati rolls (a type of Indian kebab wrapped in flatbread). Although the owner of one restaurant changed his profile picture on Facebook from a picture displaying the infringing trade dress without preserving that evidence, the court found that it would not have been immediately clear to him that changing his profile picture would undermine discoverable evidence and that any spoliation was therefore unintentional.

The Stored Communications Act

Information placed on social networking sites such as Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter is increasingly being sought by adversaries in a lawsuit. Access to this information can often make or break a case because such information may contain details that contradict (or weaken) the claims being asserted in the litigation. Limits apply to accessing this information, however, particularly as the Stored Communications Act (SCA)9 relates to discovery requests.

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

There is no expectation of privacy in information available to the public, whether posted on- or off-line. Applying this concept in the social media context, one California appellate court found that the plaintiff did not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in an article she posted on MySpace because it was “available to any person with a computer” and thus open for public viewing (and republication).10 As felicitously noted by another court, “[t]he act of posting information on a social networking site, without the poster limiting access to that information, makes whatever is posted available to the world at large.”11 Such information should be freely accessible without giving rise to an invasion of privacy claim.

The SCA was enacted because the advent of the Internet presented a host of potential privacy breaches that the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition against unreasonable governmental searches and seizures does not address. It creates a set of Fourth Amendment-like privacy protections by statute, regulating the relationship between government investigators and service providers in possession of users’ private information, including email and other digital communications stored on the Internet:

• First, the statute limits the government’s right to compel providers to disclose information in their possession about their customers and subscribers.

• Second, the statute limits the right of an Internet service provider (ISP) to disclose information about customers and subscribers to the government voluntarily.

• Among the most significant privacy protections of the SCA is the ability to prevent a third party from using a subpoena in a civil case to get a user’s stored communications or data directly from an electronic communication service (ECS) provider or a remote computing service (RCS) provider.12

![]() Note

Note

The SCA distinguishes between a remote computing service (RCS) provider and an electronic communication service (ECS) provider, establishing different standards of care for each. The SCA defines an ECS as any service which provides to users thereof the ability to send or receive wire or electronic communications—such as, for example, email and text messaging services providers. With certain enumerated exceptions, the SCA prohibits an ECS provider from knowingly divulging to any person or entity the contents of a communication while in “electronic storage” by that service.13

The SCA defines RCS as the provision to the public of computer storage or processing services by means of an electronic communications system, and in turn defines an electronic communications system (as opposed to an electronic communication service) as any wire, radio, electromagnetic, photo-optical or photoelectronic facilities for the transmission of wire or electronic communications, and any computer facilities or related electronic equipment for the electronic storage of such communications. An electronic bulletin board is an example of an RCS. The SCA prohibits an RCS provider from knowingly divulging to any person or entity the contents of any communication which is carried or maintained on that service, if the provider is not authorized to access the contents of the communications for purposes of providing services other than storage or computer processing.14

Because the SCA is silent on the issue of compelled third party disclosure, courts have interpreted the absence of such a provision to be an intentional omission reflecting Congress’s desire to protect user data, in the possession of a third-party provider, from the reach of private litigants.

For instance, in Crispin v. Audigier, Inc.,15 a California federal district court determined that the SCA applies to social media posts, provided that the poster had established privacy settings intended to keep other users from viewing the content without authorization.

In this case, the defendants issued third-party subpoenas to Facebook and MySpace, among others, to obtain all messages and wall postings that referred to the defendants. The court held that the plaintiff was entitled to quash the subpoenas (that is, have them declared void), finding that the SCA applied to these communications because the social media site providers were electronic communication services.

According to the court, the content in question was electronically stored within the meaning of the SCA and therefore could not be accessed without authorization. As a result, messages sent using the sites and content posted but visible only to a restricted set of users (that is, Facebook friends) were both subject to the SCA, and the court disallowed the defendants’ discovery request. The Crispin court drew a distinction, however, between plaintiff’s private messages and wall postings because wall postings are generally public, unless specifically protected by the user. Accordingly, the Crispin court remanded the case back to the magistrate judge for a determination of whether the plaintiff’s privacy settings rendered these wall postings unprotected by the SCA.

Although Crispin suggests that a user’s efforts to make communications on social networking sites private is a key factor in determining whether a user’s communications are protected by the SCA, some courts have still required parties to provide access to this purportedly private information.

In Romano v. Steelcase,16 for example, a New York Supreme Court ordered a plaintiff to execute a consent and authorization form providing defendants access to information on the social networking sites she utilized, including Facebook and MySpace. The defendants were entitled to this information because it was believed to be inconsistent with plaintiff’s claims concerning the extent and nature of her injuries. Indeed, the plaintiff’s public profile page on Facebook showed her smiling happily in a photograph outside her home despite her claim that she sustained permanent injuries and is largely confined to her house and bed. The information on these social networking sites further revealed that the plaintiff enjoyed an active lifestyle and traveled out of state during the time period she alleges that her injuries prohibited such activity.

As it relates to the discovery process, courts generally do not permit parties to conduct a fishing expedition—that is, to throw the discovery net indiscriminately wide hoping to find something, somewhere.17 Accordingly, a litigant will most likely not be entitled to another party’s social network information without an adequate showing of relevancy to the claims and defenses in the litigation.

For litigants seeking the contents of an adversary’s private social networking account, Crispin and Romano provide important guidance. In certain cases, as in Romano, litigants may be ordered to relinquish access to their entire social networking sites that may be relevant and material—that is, sufficiently related to, and tending to prove or disprove—the issues in the pending case, notwithstanding the party’s privacy settings. In other cases, like Crispin, access to an adversary’s social networking pages can be obtained directly by the social networking site, not by a subpoena (which the SCA generally prohibits), but rather with the consent of the user, which can be compelled by a court order.

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

In Crispin, the court quashed those portions of the Facebook and MySpace subpoenas to the extent they sought private messaging, finding such content to be protected by the SCA. However, as to the portions of the subpoenas that sought Facebook wall postings and MySpace comments, the court required additional information regarding plaintiff’s privacy settings and the extent to which he allowed access to his social media postings and comments.

Presumably, disclosure would be permitted if public access were allowed since the SCA does not apply to an “electronic communication [that] is readily accessible to the general public.”18 Importantly, Crispin addressed only the private messaging aspects of social networking websites; it did not consider whether other content on a user’s page, such as photos, videos, “likes,” subscription lists, “follows,” lists of “friends,” etc., could be disclosed in response to a subpoena.

In this regard, it should be noted that the SCA only protects “communications” from disclosure. Whether a court will interpret this term broadly enough to encompass all of the user’s information on a social media website (and not just “communications” as traditionally understood) remains to be seen.

Authenticating Social Networking Site Evidence at Trial

Documents may not be admitted into evidence at trial unless they are properly authenticated (that is, proven to be genuine, and not a forgery or fake).19 Given the anonymous nature of social networking sites, and the relative ease in which they can be compromised or hijacked, authenticating social networking site evidence is particularly challenging.

In Griffin v. Maryland,20 for example, the Court of Appeals of Maryland ordered a new trial of a criminal conviction. The court based the new trial order solely on the prosecutor’s failure to properly authenticate certain social media pages used during trial.

Authenticating social networking site evidence is particularly challenging.

During the defendant, Antoine Levar Griffin’s trial, the state sought to introduce his girlfriend’s MySpace profile to demonstrate that she had allegedly threatened a key witness prior to trial. The printed pages contained a MySpace profile in the name of Sistasouljah (a pseudonym), listed the girlfriend’s age, hometown, and date of birth, and included a photograph of an embracing couple, which appeared to be that of Griffin and his girlfriend. The printed pages also contained the following posting, which substantiated the witness’s intimidation claim:

“JUST REMEMBER SNITCHES GET STITCHES!! U KNOW WHO YOU ARE!!”

Griffin was convicted of second-degree murder, first-degree assault, and illegal use of a handgun, and was sentenced to 50 years in prison.21

On appeal, Griffin objected to the admission of the MySpace pages because “the State had not sufficiently established a connection” between Griffin’s girlfriend and these documents.22 The intermediate appellate court denied the appeal and concluded that the documents contained sufficient indicia of reliability because the testimony of the lead investigator and the content and context of the pictures and postings properly authenticated the MySpace pages as belonging to her.23

The Maryland Court of Appeals reversed this holding, finding instead that the picture of the girlfriend, coupled with her birth date and location, were not sufficient distinctive characteristics on a MySpace profile to authenticate its printout.24

First, as the court observed, although MySpace typically requires a unique username and password to establish a profile and access, “[t]he identity of who generated the profile may be confounding, because ‘a person observing the online profile of a user with whom the observer is unacquainted has no idea whether the profile is legitimate.’ ... The concern arises because anyone can create a fictitious account and masquerade under another person’s name or can gain access to another’s account by obtaining the user’s username and password.”25

Second, the court noted the potential for user abuse and manipulation on social media sites:

• Fictitious account profiles and fake online personas (spoofing)

• Relative ease of third-party access and source of information

• Potential manipulation of photographs through Photoshop

These risks require a greater degree of authentication than merely a date of birth or picture to establish the identity of the creator or user of a social networking site.26

![]() Legal Insight

Legal Insight

Courts in other jurisdictions have also wrestled with the issue of authenticating social media evidence in light of how relatively easy it is to manipulate such “evidence”. For example, in People v. Lenihan,27 a New York criminal judge refused to admit MySpace photos of the prosecution’s witnesses depicting them (together with the deceased victim) as gang members in part because of the potential manipulation of the images through Photoshop.

Likewise, in State v. Eleck,28 the Appellate Court of Connecticut agreed with the trial court’s decision to exclude from evidence a printout documenting messages allegedly sent to the defendant (Robert Eleck) by the victim from her Facebook account. Despite evidence that the victim added Eleck to her Facebook “friends” before sending the messages and removed him after testifying against him, this was insufficient to establish that the messages came from the victim, and not simply from her Facebook account.

Similarly, in Commonwealth v. Williams,29 the Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) in Massachusetts found that the trial judge erred in admitting into evidence the contents of several MySpace messages from the criminal defendant’s brother—urging a witness not to testify against the defendant or to claim a lack of memory about the events at her apartment the night of the murder—without proper authentication. According to the SJC, “[a]lthough it appears that the sender of the messages was using [defendant] Williams’s MySpace Web “page,” there is no testimony ... regarding how secure such a Web page is, who can access a Myspace Web page, whether codes are needed for such access, etc. Analogizing a Myspace Web page to a telephone call, a witness’s testimony that he or she has received an incoming call from a person claiming to be “A,” without more, is insufficient evidence to admit the call as a conversation with “A.” ... Here, while the foundational testimony established that the messages were sent by someone with access to Williams’s MySpace Web page, it did not identify the person who actually sent the communication.” 30

The Griffin court proposed three methods by which social media evidence could be properly authenticated (in both criminal and civil cases):

• Deposition testimony—At deposition, the purported creator can be asked if he/she created the profile and the posting in question. Although the Fifth Amendment’s protection against self-incrimination precludes a criminal defendant from being forced to testify, no similar restrictions exist in the civil context.

• Forensic investigation—The purported creator’s computer’s Internet history and hard drive can be examined to determine whether that computer was used to originate the social networking profile and posting in question. An inspection of a computer’s and mobile phone’s evidentiary trail is a valuable means of establishing whether the subject hardware included the actual devices used in originating the profile/posting.

• Subpoena third-party social networking website—A subpoena to the social networking website provider can be issued to obtain information related to the purported users’ accounts and profiles, and that “links the establishment of the profile to the person who allegedly created it and also links the posting sought to be introduced to the person who initiated it.”31

Businesses—and their attorneys—should move to preclude any adverse postings allegedly from their employees that are not properly authenticated.

Businesses can cite the following factors as additional grounds to challenge the authenticity (and thereby seek to preclude the admissibility) of potentially damaging social networking site evidence:

• Whether the social networking site allows users to restrict access to their profiles or portions thereof

• Whether the account in question is password protected

• Whether others have access to the account

• Whether the account has been hacked in the past

• Whether the account is generally accessed from a public or private computer

• Whether the account is generally accessed from a secured or unsecured network

• Whether the posting in question came from a public or private area of the social networking site

• Whether the appearance, contents, substance, internal patterns, or other distinctive characteristics of the posting, considered in light of the circumstances, show it came from a particular person

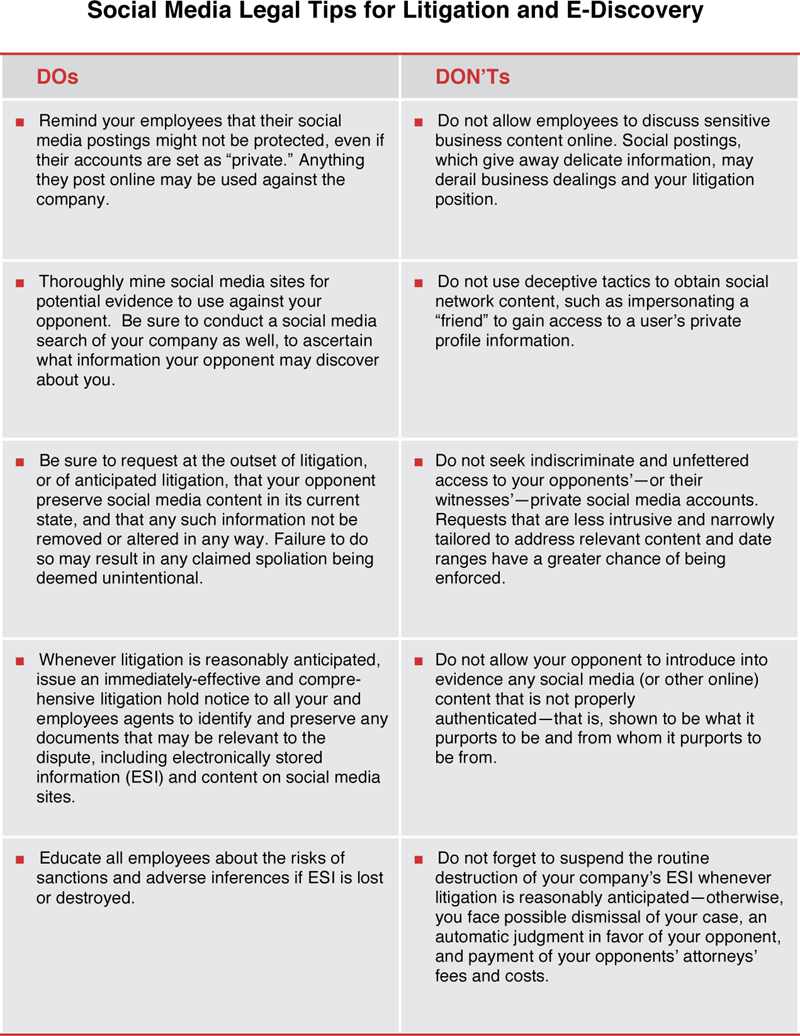

The challenges associated with an increase in legal liability arising from ESI and social media information (and their preservation and proper destruction) may be painful, particularly for companies with limited resources. The tips outlined in Figure 5.1 serve as actionable guidelines for mitigating the risks social media may present in the litigation of business disputes.

Figure 5.1 Social Media Legal Tips for Litigation and E-Discovery.

Chapter 5 Endnotes

1 Offenback v. LM Bowman, Inc. et al., Case No. 1:10-CV-1789 (M.D. Pa. June 22, 2011)

2 EEOC v. Simply Storage Mgmt., LLC, 270 F.R.D. 430 (S.D. Ind. 2010)

3 Largent v. Reed, 2009-1823 (Pa. C.P. Franklin Co. Nov. 8, 2011) (“There is no reasonable expectation of privacy in material posted on Facebook.” “Only the uninitiated or foolish could believe that Facebook is an online lockbox of secrets.”)

4 Barnes v. CUS Nashville, LLC, Case No. 3:09-CV-00764 (M.D. Tenn. June 3, 2010)

5 See, for example, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 26(b)

6 See, for example, Romano v. Steelcase, 907 N.Y.S.2d 650 (N.Y. Sup. Ct., Suffolk Co. 2010); Patterson v. Turner Construction Co., 931 N.Y.S.2d 311 (N.Y. App. Div. 2011) (“The postings on plaintiff’s online Facebook account, if relevant, are not shielded from discovery merely because plaintiff used the service’s privacy settings to restrict access..., just as relevant matter from a personal diary is discoverable.”)

7 See, for example, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 26(a)(1)(A)(ii)

8 Katiroll Co. v. Kati Roll and Platters, Inc., Case No. 3:2010-CV-03620, Docket No. 151, Memorandum Order (D.N.J. Aug. 3, 2011)

9 18 U.S.C. § 2701 et seq.

10 Moreno v Hartford Sentinel, Inc., 91 Cal. App. 4th 1125 (2009)

11 Independent Newspapers, Inc. v. Brodie, 966 A.2d 432, 438 n 3 (Md. 2009)

12 See 18 U.S.C. §§ 2702(a)(1) and 2702(a)(1)(a)(2)

13 See 18 U.S.C. § 2702(a)(1)

14 See 18 U.S.C. § 2702(a)(2)

15 Crispin v. Audigier, Inc., 717 F.Supp.2d 965 (C.D. Calif. May 26, 2010)

16 Romano v. Steelcase, 907 N.Y.S.2d 650 (N.Y. Sup. Ct., Suffolk Co. 2010)

17 See, for example, Caraballo v. City of New York, 2011 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 1038, at *6 (N.Y. Sup. Richmond County, Mar. 4, 2011) (Defendant’s motion to compel discovery of plaintiff’s social networking site information denied because “digital ‘fishing expeditions’ are no less objectionable than their analog antecedents.”)

18 18 U.S.C. §2511(2)(g)

19 See, for example, Federal Rules of Evidence, Rule 901(a), which provides: “The requirement of authentication or identification as a condition precedent to admissibility is satisfied by evidence sufficient to support a finding that the matter in question is what its proponent claims.”

20 Griffin v. Maryland, 19 A.3d 415 (Md. Apr. 28, 2011)

21 Griffin v. Maryland, 995 A.2d 791 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. 2010)

22 Id. at 796

23 Id. at 806–807

24 Griffin v. Maryland, 19 A.3d 415, 424 (Md. Apr. 28, 2011). Note: Under Federal Rules of Evidence, Rule 901(b)(4), a piece of evidence may be authenticated through its “appearance, contents, substance, internal patterns, or other distinctive characteristics, taken in conjunction with circumstances.”

25 Id. at 421

26 Id. at 424

27 People v. Lenihan, 911 N.Y.S.2d 588 (N.Y. Sup. Queens Cty. 2010)

28 State v. Eleck, 130 Conn. App. 632 (Conn. App. Ct. 2011)

29 Commonwealth v. Williams, 456 Mass. 857, 926 N.E.2d 1162 (Mass. 2010)

30 Id. at 869

31 Griffin v. Maryland, supra, at 428