Chapter 4: Shaping a Disruptive Solution: Novelty for Novelty’s Sake Is a Resource Killer

It’s not enough just to come up with something disruptive; it has to be disruptive in ways that are valued by users.

“Your company’s chance of creating new wealth is directly proportional to the number of ideas it fosters and the number of experiments it starts. So ask yourself, ‘How diverse is your company’s portfolio of unconventional strategy options?’”

—Gary Hamel1

One of frog design’s clients, a major beauty-products manufacturer, came to us looking for a way to extend one of its most successful products, a microderm abrasion skin rejuvenation kit, which was aimed at older women. The company’s idea was to combine microderm abrasion technology with its skin-cleanser line and create a new handheld product aimed at a younger crowd. They came to frog design to help them design the new product.

Initially, the client targeted its new offering at women 25–45, but after we tested that initial hypothesis, we discovered that the real opportunity was with the tween-to-early 20s demographic. Because buyers of most of the company’s products were typically older than that, even considering marketing to younger consumers meant understanding a new market.

We began by deeply immersing ourselves in the habits and behavior of typical customers of skincare and personal-health devices. By doing extensive interviews and in-home observations, we came to understand how skincare rituals fit into young women’s daily lives and physical environments. We also discovered that nearly every woman—rich or poor, living in a tiny studio apartment or a huge suburban mansion—had a box somewhere in her house filled with unused or underused skincare and healthcare products.

These observations yielded a set of insights, which our designers used to generate a number of exciting ideas around color, form, and materials. At least they seemed exciting to our design team, which consisted of a handful of talented, 30-something men and women. There wasn’t a single teen girl in the bunch—and that was a problem.

Disruptive ideas are great, but they’re only half the story. Unless those ideas can be made feasible, they can’t deliver value. How do you know whether an idea is feasible? Well, you don’t—unless you actually see how it plays with your target market. Without testing our ideas with prospective end users and consumers, we were in danger of coming up with some really terrific ideas that would completely flop when they hit store shelves.

Let me give you a few more examples. Do you remember smokeless cigarettes? With all the talk about cancer and second-hand smoke, smokeless cigarettes would seem like a slam dunk. The only problem is that the people who really want smokeless tobacco are the ones who are standing next to the smokers. Apparently, smokers themselves aren’t interested. And because non-smokers rarely buy cigarettes, smokeless or not, what must have seemed like a great idea (probably developed by a bunch of non-smokers) died a quick death. The ending to this story might have been different if someone had thought to test the product out on actual smokers.

The Edsel has earned a place in marketing lore as perhaps one of the biggest corporate blunders of the past few centuries.2 The story has been hashed and rehashed in countless articles and business-school case studies. But there’s one aspect of the story that doesn’t get much attention: the Teletouch, a pushbutton automatic transmission interface that was located in the center of the steering wheel. A beautiful, innovative design, no doubt. But Ford’s engineers were working in a secretive bubble and wouldn’t let anyone see or interact with the new car. As a result, when the car was finally released and people actually had a chance to test-drive it, they absolutely hated that every time they wanted to honk their horn, they accidentally shifted gears. We’ll talk more about the Edsel later, but suffice it to say here, that’s the kind of thing that happens when designers and end users are kept away from each other.

Drivers hated that every time they wanted to honk their horn, they accidentally shifted gears.

In this chapter, we change our focus from conceiving ideas to turning those ideas into practical solutions. The difference between an idea and a solution is that the latter is always feasible. If it’s not, it’s not really a solution. At the end of the previous chapter, you generated three disruptive ideas, which may or may not be practical. By the time you’re done with this chapter, you’ll have refined one or more of those ideas into something that’s truly workable.

The best way to get from disruptive idea to practical solution is to actively involve end users to test and review. I know that may sound like a traditional focus group, but it’s not. Participants actually become part of a collaborative, creative process. Of course, you have a far greater understanding of the project than they do, but they’re still a critical reality check. They’re now the experts, and you’re not behind the glass in another room observing. You’re working together, not only to evaluate and validate ideas, but also to work on improvements. In a very real sense, you’re co-creating a solution.

Why is this important? Because, as the stories of smokeless cigarettes and Teletouch gearshifts illustrate, it’s not enough just to come up with something disruptive; it has to be disruptive in ways that are valued by users. Novelty for novelty’s sake is an indulgence and a waste of resources.

In the second part of the chapter, we’ll talk about how to synthesize the information and feedback you get from consumers into a tangible prototype of your solution. (And yes, even services have a tangible component, which we’ll discuss in detail.)

What Do People Really Think?

(As Opposed to What They Tell You They’re Thinking)

Facilitating feedback from prospective end users is a critical component of the process because it can reveal the gaps between what you claim you want to accomplish with your idea and what you are actually willing (or able) to do. It may also reveal that those ideas you thought were so disruptive aren’t really so hot after all. Better to find that out right now than after you’ve sunk a ton of money into implementation. There are three basic ways of recruiting consumers for research. First, you could hire one of the many companies that do this kind of thing professionally. You give them a list of the characteristics you’re looking for (more on that later). They then go through their databases and come up with a large group of likely prospects, whom they prescreen, screen, weed out, and eventually give you a solid shortlist.

Second, if you haven’t got the budget (and, believe me, the professional route is not cheap), you can go guerilla and find your own participants by posting ads on online bulletin boards, such as Craig’s List.

Third, you could tap into your network of friends and family. Although this is definitely the cheapest way to go, I don’t often recommend it, in part because of what you might call “the mom effect.” That’s when people (like your mom) tell you that all of your ideas are great just the way they are. And you’re cute, too. This kind of feedback is useless. Because the professional option isn’t a possibility for many companies, let’s talk about how the guerilla method works.

Your first order of business is to come up with a description of the kind of person you think is your target consumer. (You’d do this step when working with professional recruiters or identifying family and friends, too.) In our microderm abrasion example, that company was looking for females age 12-24 who

• Had used some kind of microderm abrasion (MDA) kit, either made by our client or a competitor, or had visited a dermatologist for MDA or other facial treatment

• Owned at least one MDA kit

Then, you craft a short ad and post it on Craig’s List or another similar site. You want to be provocative yet vague. For example, “Are you a female between the ages of 12 and 25? Are you interested in participating in the design process for a new skincare product?”

Chances are, you’ll get a flood of responses. Eliminate the ones that are obviously inappropriate (the people who clearly didn’t read your ad and think you’re hiring telemarketers, the ones who want to sell you something that will expand various parts of your anatomy, and anyone else who’s completely off base). That should leave you with a pool of about 20-30 people.

Next, conduct email follow-ups. After a few rounds of email questions, you should be able to narrow the pool to about a dozen potential subjects. Now, it’s time to pick up the phone and make your final choices. Keep in mind that this isn’t about putting together a huge, statistically significant sample. It’s about generating rich insights and exploring nuances in detail. Ideally, you’ll hone your choices to nine participants: three teams of three. If you can’t get to nine, six will pass. If you absolutely have to, three will do in a pinch. But, don’t go lower than that.

The microderm abrasion project required a group of highly experienced and engaged subjects. Here’s what the final nine looked like:

• They responded in a timely way to our email communications (all).

• They answered product questions quickly (all).

• Worked full time (at least 3).

• Worked part time (at least 3).

• Had visited a dermatologist for MDA and facial-related treatments (2).

• Had a history of microderm abrasion use (all; professional 2).

• Owned one of our client’s MDA kits (3).

• Owned a competitor’s kit (all).

• Had used two or more MDA systems (4).

• Had positive results with MDA systems (4).

• Had negative results (at least 2).

After you finalize your participants, bring them into your office (or wherever you’ll be doing the testing), where, over the next few hours, you’ll run them through the following five activities3 (we’ll discuss each one in detail):

1. Memory mapping

2. Individual ranking

3. Group ranking

4. Improvement exercise

5. Open discussion

Memory Mapping

After a brief introduction where you tell the participants about the project, you’ll ask them to think about the situation you’re focused on and draw—from memory—the product or service they currently use. This technique won’t give you a reliable indication of consumers’ preferences or purchase intentions. But you’re not using it for that, anyway.

If you’re planning on introducing a marketplace disruption, you need to know what your customers’ mental models are and whether your solution violates their “rules” for how they think it should be used. Asking your participants to verbally describe a product or service won’t do the job. Having them physically draw it out (even in the most rudimentary way) is critical. You need to see how it’s laid out, how it functions, and how they see it in action. That way, if any of the participants say they hate your idea, you’ll have a much better idea why.

Problems happen when there’s a disconnect between your end user’s mental model and yours. Designers know a lot about how their new ideas will work, but little about how people will actually interact with them. Conversely, end users know how they will (or would like to) interact with things, but not much about how you’d like to have them work.

Just to be clear, I’m not saying that you should never violate your consumers’ rules or mental models. Not at all. The point I’m making is that breaking models is actually a good thing—as long as you have a compelling reason for doing so. Imagine that one of your disruptive ideas is a new remote control with the power button in the lower left corner. If all of your participants drew remotes with power buttons in the upper right, you’ll know that if you insist on the lower left placement, you’re going to need a much better reason than, “It looks kinda cool there.” If you don’t have one, you’ve got no business trying to change anyone’s mental models.

A participant drawing a product from memory.

To reach a feasible solution, you need to balance the magic, mystery, and creative intuition that lead you to your disruptive ideas with the messy, real, unpredictable pressures of the market. In other words, you need to close the loop between the end user’s mental model and yours. If Edsel’s engineers would have asked people to draw an automatic transmission gear shifter, they would have gotten pictures of steering-column levers or four-on-the-floor. They would have known that they were breaking an important rule and might have reconsidered their plan to put push buttons in the center of the steering wheel where the horn usually goes. (But again, just because an idea violates a mental model is not always a justification for tossing it. We’ll talk about this later.)

Individual Ranking

Before you conduct this exercise, you should have a clear idea of the attributes that you expect your solution to have. For example, the attributes we used for our client were

• Elegant

• Clear

• Affordable

• Special

• Fun

As you can see, these values are extremely broad. Write all of your attributes in a column on a sheet of paper with a 1-5 scale next to each one. Give one of these worksheets to each participant.

Then, introduce your ideas, one at a time, to the participants as a group. Ask them to refrain from commenting while they’re listening, and then ask participants to rate the ideas according to the attributes on the worksheet you just gave them, with 1 being the lowest grade and 5 the highest. On the same sheet, ask them to summarize their first impressions of the idea. You’ll go through this sequence for each disruptive idea. (You’ll need separate worksheets for each idea; the attributes remain the same.)

The important thing to remember about this exercise is that it must be a 100-percent individual effort. Participants should not discuss their ratings or talk about what they’re writing. Having them individually rate the ideas really cuts down on groupthink and follow-the-leader mentality. The more comments like, “I agree with Bob…,” the less helpful the results.

After all the participants finish their individual worksheets, open up the discussion and encourage them to talk about their reactions to the ideas. Then, have them return to the sheets and write down how/whether their impressions have changed.

Participants individually rating ideas.

Group Ranking

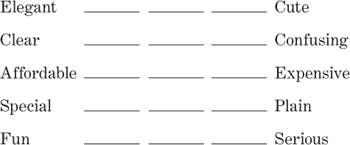

After a little group discussion, you’ll give each three-person team a new worksheet. This one will have a list of attributes in a column down the left edge of the paper. For example:

• Elegant

• Clear

• Affordable

• Special

• Fun

Down the right edge, you’ll list the polar opposites. For example:

• Cute

• Confusing

• Expensive

• Plain

• Serious

Between the two columns, you’ll leave one short blank line for each idea. The blank sheet will look something like this:

Now, give each team a sheet of colored dots—one color per idea—and ask them to work together to order the ideas in relation to each other within each of the polar categories.

Your task here is to facilitate a discussion in which the participants negotiate with each other to determine where the dots should go. You want to hear their arguments and their reasoning. But most of all, you want them to try to convince each other and come to a final decision as a group. Having spent some time thinking about the ideas individually should reduce the amount of leader following that goes on. It’s kind of like going out refrigerator shopping with a family member. Each of you will point out to each other things the other hadn’t seen.

The final step is to get the participants to come up with a favorite overall choice.

Participants working together to rank ideas.

Improvement Exercise

After getting individual and group feedback on each of your ideas from your participants, the next activity is to bring them into the process of constructively improving those ideas. Our goal here is to hone the range of ideas you started with into one practical, workable direction.

Looking at the arrangement of the dots in the previous step, you may see that there’s one clear winner, one idea that scored at the top on nearly every attribute. If that doesn’t happen (and it’s generally rare), don’t worry. The solution is to create a hybrid: a single idea that incorporates the best features of each of the three options your group participants have evaluated.

Every time I run this exercise, whether it’s running workshops, teaching MBA students, or working with clients, I’ve found that the group participants really get into it, especially if they’re encouraged to think of themselves as integral to the creative process and not simply being focused grouped or interviewed.

Open Discussion

Now that your participants have thought about and played with your disruptive ideas, and they have a good sense of how the various attributes could impact them, this is the perfect time to take 15 minutes or so to ask them about value. The best way to do this is to come right out and ask them, “How much would you pay for this product or service?” There’s no other way to find out what that is than to inquire. Even though you’re asking for numbers, you’re not actually going to use this information to set the price of the offering. You’re gauging their level of enthusiasm.

Before you send everyone home with their thank-you gifts, take one last moment to summarize what they liked and didn’t like about each idea.

As you mentally process all the information you’ve gathered from your participants, it’s important to keep a cool head. Yes, you should listen to prospective end users. But, be reflective. Consumers sometimes need guidance, and slavishly following their wants and desires can land you in real trouble.

One of my favorite episodes of The Simpsons (called “Oh, Brother, Where Art Thou?”) nicely illustrates this point. Grandpa confesses that Homer has a half-brother, whom Homer immediately tries to track down. He eventually discovers that his brother is Herbert Powell, the head of a car manufacturer. Herb then decides that Homer, being an average American, is the perfect person to design a new car for his company. He gives Homer free rein in the design, and, as you might expect, Homer is determined to build the car with all sorts of wild effects, like bubble domes, tail fins, and several horns that play “La Cucaracha.” At the unveiling of the new car, Herb is horrified to find that, besides being hideous, the car costs $82,000. Herb’s company declares bankruptcy.

This raises an important question: When do you go with what your customers tell you, and when do you overrule them? Unfortunately, there’s no simple answer.

In his best-selling book Blink, Malcolm Gladwell talks about how chair manufacturer Herman Miller developed the Aeron, and the dilemma the company faced when trying to measure people’s reactions to new ideas: “It is hard for us to explain our feelings about unfamiliar things,” Gladwell writes. The Aeron chair was a deliberate attempt by Herman Miller to design something different; the most ergonomically correct chair ever. As Gladwell points out, “In Herman Miller’s years of working with consumers on seating, they had found when it comes to choosing office chairs, most people automatically gravitated to the chair with the most presumed status—something senatorial or throne-like, with thick cushions and a high, imposing back.” (Sounds a lot like one of the clichés we discussed in Chapter 1, doesn’t it?) “What was the Aeron?” Gladwell continues, “It was the exact opposite: a slender, transparent concoction of black plastic and odd protuberances and mesh that looked like the exoskeleton of a giant prehistoric insect.”4

Sounds a lot like a disruptive hypothesis, doesn’t it? Here are some of the responses Herman Miller got from testing:

• It looks like it came from the set of Robocop.

• The wiry frame will not have the strength to hold a person.

• It resembles lawn furniture.5

As Herman Miller discovered with the Aeron chair, we often react badly to things we aren’t familiar with.

Consumers had a clear mental model of what an office chair should look like, something throne-like with thick cushions and a high imposing back. They were unsure what to make of this “exoskeleton of a giant prehistoric insect.” It was comfortable, but ugly. “And if there was one thing that Herman Miller knew from years and years in the business, it is that people don’t buy chairs they think are ugly.” We often react badly to things we don’t understand or that we aren’t familiar with. But, as just mentioned, that doesn’t always mean that the idea is without merit.

I’m sure you already know the rest of the story; you may even be sitting in it. Herman Miller didn’t kill the project or cover the chair with padding. The company’s decision makers trusted their instincts, and the Aeron chair went on to become one of the biggest product successes of the last decade. What was once ugly has become beautiful, and Gladwell finishes this thought by suggesting that “the problem with market research is that often it is simply too blunt an instrument to pick up the distinction between the bad and the merely different.”6

The important thing in this process is to realize that new offerings (from the evolutionary to the revolutionary) take time for consumers/users to understand and get used to. So, you need to listen and observe their reactions, but be sure to listen and observe in the right way. Facilitating end user feedback in the way I’ve just described helps you create a distinction between quality and difference.

Which Idea Should You Use?

(Introducing Mr. Potato Head)

In the previous step, you had real live prospective customers help you refine your ideas. They compared, contrasted, told you what they liked, and what they didn’t like. Now, it’s the moment of truth: Which idea are you going ahead with? Well, as I hinted at earlier, the one you pick may not necessarily be the “winner” from the user testing. In fact, it’s more than likely that you’ll end up combining attributes from all three. That’s the “Mr. Potato Head” part of the process. You start with your basic potato, add various features, and tinker until you’re completely satisfied. Don’t like the eyes? Take them off and put on sunglasses. Don’t like the bald head? Add a hat. Think he’d look better with his nose on top of his head instead of in the front? Give it a try.

It’s pretty much the same with your disruptive ideas. You start off with your basic potato, get rid of some of the things that don’t work, and add a few from other potatoes that do a better job until you’re able to clearly communicate your message. To help you through this process, we’re going to create several prototypes—rough mock-ups of your selected idea; this is not a perfect, complete rendition of your product or service. Creating these prototypes allows you to better visualize, understand, and transform your disruptive idea into (finally!) a solution.

The results of prototyping—and its close relative, simulating—are all around us: movies, airplanes, automobiles, microprocessors, personal computers, software, gene sequencing, biotechnology, and even the Internet. But, as Michael Schrage writes in his book Serious Play, “The value of prototypes resides less in the models themselves than in the interactions—conversations, arguments, collaborations—they invite.”7

Prototypes create a “shared space” for senders and receivers to communicate. As Schrage says, “Creating a dialogue between people and prototypes is more important than creating a dialogue between people alone.”8 Why? Because it’s easier for people to express what they desire by reacting to prototypes than by verbalizing their needs. (This is absolutely critical. I couldn’t possibly count the number of clients—and designers—who thought they wanted a particular button in a particular place, or swore up and down that some feature or other was vital. But after they had a chance to hold a prototype in their hand, they changed their minds completely.)

Prototypes make thinking tangible. They give shape to your ideas. Literally.

Prototypes make thinking tangible. They give shape to your ideas. Literally. They help highlight the context in which something will be used, uncover flaws in your assumptions, and help identify what’s being left out (or what should be). But, perhaps their most important function is to force you to face up to the practical compromises that you’ll inevitably have to make to deliver value to your market. In other words, it may turn out that your wonderful vision can’t actually—and practically—be turned into a reality.

Be Quick and Dirty

The prototypes that I produce for my clients—and that I want you to produce—are supposed to be rough. I know it’s tempting to try to create something really beautiful. But, I can tell you that the rougher the prototype, the more likely people are to get involved and work on it—and that’s exactly what you want. The more refined it looks, the less people want to tinker with it.

The difference between the touchable and untouchable is what we, in design, call “fidelity.” Low fidelity is cheap, easily changed, and can be thrown away without anyone worrying too much about it. Low-fidelity prototypes tend to encourage participation and dialog. High fidelity is expensive, well made, and much closer to the actual look and feel of a product or service. But you’ll find, as many others have, that as the prototyping materials and the look and feel tighten up, so does a lot of the thinking.

You’ve probably noticed that I’ve been referring to prototypes—plural. That right there is one of the differences between design-oriented companies and non-design-oriented ones. In design, we always create multiple prototypes of the same idea. That helps us refine and change things around until we get it right. Non-designers tend to try to create and perfect only one.

It’s important to keep in mind that we’re operating in a time-limited context. That means that your prototypes should be “satisfactory” as opposed to “optimal.” Big difference. Here’s a good example:

On April 11, 1970, the Apollo 13 Mission to the moon launched. Fifty-six hours into the flight, an electrical failure in the command module required the three-person crew to retreat to the lunar lander. The carbon dioxide filters of the lunar lander were engineered to support two people for two days, which was the planned duration of the lunar landing. But to get everyone safely back to earth, they would have to support three people for four days. The square carbon dioxide filters of the forsaken command module had the capability to filter the excess carbon dioxide, but they wouldn’t fit into the round filter receptacle of the lander.

On the ground, NASA engineers figured out how to construct a makeshift adaptor for the square command module filters (in other words, how to plug a square peg in a round hole). With time quickly running out, ground control instructed the astronauts on how to put together the adapted filters, using materials available on the spacecraft such as duct tape, covers from logbooks, and plastic bags. The makeshift adaptor wasn’t perfect, but it solved the urgent problem of carbon dioxide poisoning. Had the engineers insisted on creating a perfect solution, they would never have finished in time.9

The bottom line is that, at this stage, prototypes beyond the satisfactory yield diminishing returns.

Iteration Cycles

Any idea can be expressed in a variety of ways. For example, if your idea is for a cup, you’ll have to consider size, material, color, weight, location of the handle, whether or not it has a lid, and so on. You’ll be developing your prototypes through a series of three design iterations, which will progress from low fidelity to slightly higher fidelity as you refine the idea and learn more about how it will be used.

In the context of design, the word iteration refers to the process of exploring variations of the prototype, continually shaping and tuning the idea. At the end of each cycle, the prototype is reviewed with other people and “iterated” in the next cycle based on feedback. Each cycle of iteration narrows the range of possibilities until the idea takes the shape of a feasible solution.

Set Up a Review Team

Never review the results of an iteration cycle by yourself. At a minimum, you should have one other person help you. More is definitely better. Other people will bring different perspectives and will see things in your prototypes that you can’t or don’t. They’ll probe you for details that you forgot or thought were irrelevant.

So, who are these other people? You’ll get the best results when your review team includes a broad range of perspectives. Ideally, include members of the target audience in one or more of the iterations to verify design requirements. Also, include stakeholders who will build or sell the idea. Their perspectives could be extremely valuable. If you think that I’m being a little vague, you’re right. Normally, I try to be as specific as possible, but at this stage, every company’s disruptive ideas, circumstances, finances, and philosophy are so different that there’s no way to come up with a precise breakdown of the “other people” that will work for everyone—or anyone.

Never review the results of an iteration cycle by yourself.

I recommend small group sessions of no more than 3–5 people. If your team is larger than that, you can run several sessions in parallel, where participants can work in teams of two or three. Review sessions are typically scheduled as small group sessions and last for 90–120 minutes. This allows a few minutes for a brief explanation of the prototype and still leaves plenty of time to play freely with it.

Recording Information

As you and your review team are working with and evaluating your prototypes, you should be collecting as much data from as many sources as you possibly can. On Post-Its, write interesting snippets of conversations, observations, comments, problems, obstacles, opportunities, strengths, weaknesses, faults and defects, cultural influences, questions, insightful quotes, and anything else that could possibly help with the next round of iterations.

What’s Your Disruptive Solution?

(Three Rounds of Prototyping)

Low-fidelity prototypes often consist of any of the following: paper, wire-flows (which are web-page mock-ups), foam-ware, clay, 3D printing (also known as “soaps”), and Velcro modeling, as well as click-through simulations and scenarios. Because your goal is to elicit the largest amount of useable feedback for the least investment in time and money, the materials you use will vary according to the situation you’re in. That said, let me walk you through a three-round process that uses three different prototyping methods: one for the service and information components of your disruptive idea, one for the product component, and one that pulls all the pieces together.

Round 1: The Storyboard. Grab Some Paper.

When most people hear the word “prototype,” they imagine that it’s referring to a physical thing. But, as Michael Schrage writes, “A prototype isn’t merely a prop on the organizational stage; it is a character in a marketplace narrative.”10 So in Round 1, I want you to think about your prototype as a character in a big-budget movie.

Looking at it that way, the fundamental question isn’t, “What kind of prototype should I be building?” The reality is that the story is about the interactions end users will have with your disruptive idea. Or, as we at frog design like to say, “You aren’t designing a product or a service. You’re designing an experience.” So, the question you should ask is, “What kind of interactions do I want to create?”

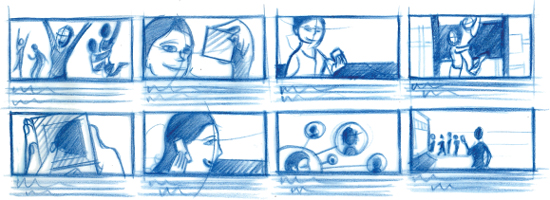

At this point, another perfectly reasonable question might pop into your mind: “How can I possibly make a physical mock-up of an experience?” The answer is that you’re going to create a storyboard—just like the ones you may have heard about in the film business. But, instead of frame-by-frame drawings of important scenes, you’ll be sketching step-by-step pictures of how people will accomplish specific tasks when interacting with your new offering. Storyboarding ensures that you won’t overlook any intentions you might have or steps that might be critical to the end users’ experience.

In one of my classes at NYU, several teams of students were working on creating new taxicab experiences. Storyboards were the perfect way to get their ideas across. They had drawings of what would happen when the customer first entered the cab, what was going on inside the cab during the ride, and what the customer’s experience was at the end.

Think of a storyboard as a kind of comic book strip consisting of both pictures and words. But don’t worry about your drawing skill or lack thereof. Stick figures, speech bubbles, arrows, and the like are all you need to get your message across. Simply draw a separate picture for each action the consumer takes while experiencing the key aspects of your idea. Add words to explain what’s happening and include close-ups of details where needed.11

A prototype is a character in a storyboard narrative.

Round 2: The Mock-Up. Grab Some Velcro and Cardboard.

In this round, you’ll create a three-dimensional “mock-up” of the overall structure for your product, as well as suggestions for functionality, use, and integration with your service and information components. This is a quick and inexpensive exercise that serves as an effective way of gaining additional input from your review team and learning how various elements of the product or task relate to one another.

This sounds like a product-centric approach—where do we put the buttons on our remote? But, even if you’re creating a service, chances are you’ll need some props. If you think about it, there are tangible elements to almost any service. And, in many cases, for the experience to work at all, you’ll need some tangible elements. In the taxi experience, for example, one team wanted to incorporate a rating system so that riders could increase their chances of getting a good driver (safe and knowledgeable, for example). They came up with—and mocked up—a new rooftop light that displayed the driver’s rating in stars, kind of like an Amazon.com or C-Net review. Another team wanted to create a taxi service for parents and children who need car seats. One of the things they had to mock up was a new kind of seat that swiveled around so that parents sitting in the front of the cab could easily turn around and interact with their kids. At the least, creating 3D prototypes gave them a chance to have a prop to demonstrate while explaining the new service to others.

To prepare, make a trip to the craft and/or hardware store to gather inspiration or use everyday household items. The exact materials you’ll need will depend on the project, but here are some basics that should be in every prototype kit:

• Foam or plastic shapes: cones, balls, and cylinders in a variety of sizes

• Velcro, glue, felt, and duct tape

• Stickers: large, small, round, rectangular, colored

• Buttons, knobs, switches, caps, hinges

Generally speaking, the bigger the variety of materials you have available, the less constrained you’ll be in creating and modifying your prototype. After you establish a basic features list, make sure there are a variety of items available that could fulfill that function. For example, you don’t necessarily need real, live buttons or switches from a hardware store. You could use stickers, construction paper, tape, or simple illustrations instead.

You can construct your mock-up anyplace where there’s a table that’s big enough to spread out and build on. You may find it helpful to keep a stash of materials in small plastic bins or boxes so you can move your model-making workshop around anywhere you need to.

Round 3: The Video and/or Photo Scenario. Grab Your Camera.

As much as I love doing things on paper, there are some limitations. Perhaps the most important is that, with a paper prototype, it’s difficult to show how you intend for something to be used. Sure, you can tell people about it; but if your idea is truly disruptive, people may need guidance on how to implement whatever it is that you’re offering.

In this round, you’ll produce a series of photos—or video scenes—of someone actually going through the entire experience in the actual environment. You may have a paper, wire, and foam mock-up of a taxicab swivel chair for parents, but in this round, you’ll show a parent in a cab actually turning around to wipe some drool from a baby’s chin. If you designed a new system that allows you to control every electronic device in your home, you’ll show someone coming home and using the keypad to turn on the lights, preheat the oven, and start downloading her email. You might also show someone sitting in an office, taking care of the same tasks remotely via cell phone, or receiving a text message alerting the user that the burglar alarm went off. And, if you’ve designed a new web-based business, you’d show people navigating the pages, finding the information they need, placing orders, and so on.

The bottom line is that video (or, to a lesser extent, still photographs) can help people better imagine and envision how one could best leverage your idea by showing it in use and in context.

One last thing: You won’t be entering your video prototype in the Sundance film festival. You’re not going for award-winning performances, snappy dialog, or innovative camera techniques. This is a quick-and-dirty reel that you can shoot on any device and in any format—just as long as you have some rudimentary editing capabilities.12

Think Outside the Socks! The Disruptive Solution

Before they went into production with any of these ideas, Jonah and his partners wanted to get feedback from their target audience and the retail buyers they would have to sell to. First, they needed to test the names they were considering for the company. So, armed with sheet of paper with different possible character names they had generated—like Miss Matched, Mismatched, Little Miss Matched, and so on—Jonah hit the streets of San Francisco and asked random tweens to tell him what they thought of each name. The winner, hands down, was Little Miss Matched, which was, in a sense, a triple entendre: A young miss who’s all about matching, a young girl who’s mismatched, and the fact that all of us feel a little mismatched now and then. The biggest clue that he was on the right track with Little Miss Matched was that everyone who saw that name smiled. It was a truly emotional response, not an intellectual one.

The watercolor paintings of sock patterns were great—and actually helped the company secure a small amount of seed money. But, to fully refine their idea into a market-ready solution, they had to produce some prototypes—actual socks that people could see, feel, and understand. The three partners were able to line up a meeting with the hosiery buyer for the entire Nordstrom chain. They presented their prototypes and, just a few minutes into the meeting, the buyer announced that the idea was “terrible” and asked why they thought she would possibly be interested.

Fortunately, the Little Miss Matched partners were clearheaded enough to ask the buyer—who’d mentioned that she had an 8-year old daughter—to take some of the samples home and get the girl’s opinion. Two days later, the buyer called back with an order for $250,000 and brand placement in all Nordstrom stores.

Although I’ve been using Little Miss Matched as an example of how to implement the steps I’m outlining in this book, they also managed to fall into several of the traps I mentioned. For example, being design-minded, they wanted to create some unique packaging to display their first orders. So, they came up with something truly superb, innovative, dramatic… and completely impractical. The designers failed to anticipate how aggressively customers handle merchandise in the retail stores. The packages looked great but they wouldn’t stay closed, leaving piles of Little Miss Matched socks all over the floor.

Use the following sample agenda to facilitate discussion, guide your thinking, and assist participants in improving on the ideas:

• Introduction (15 minutes).

• Who you are.

• Today’s agenda.

• What your goals are.

• Go through the five steps:

1. Memory mapping (15 minutes): Ask participants to draw, from memory, the product or service they currently use. What are their thoughts and feelings about the situation at hand?

2. Individual ranking (15 minutes): Guide participants through each idea, allowing them to ask clarifying questions while reviewing the idea visualizations. Ask participants to rate the ideas’ attributes on a 1–5 scale.

3. Group ranking (15 minutes): Participants use a worksheet that lists attributes and their polar opposites. You give them color-coded dots that represent each idea and have them work as a team to order the ideas relative to each other.

4. Improvement exercise (15 minutes): Participants work collaboratively to mix-and-match attributes and features from the ideas they have been shown to create one idea that the group agrees to be ideal.

5. Open discussion (15 minutes): Talk directly about what they value.

Use the following three rounds of prototyping to shape your ideas into a single disruptive solution:

1. Choose where to begin your story.

2. Select a sequence of interactions that communicate how a user experiences your idea.

3. Collect information from your research that will help craft the story: observations, insights, and so on.

4. Create the storyboard frames with pictures and words. Put only one action step within each frame.

5. Review with the team and record feedback.

1. Preparation: Consider a number of basic or possible forms that a product could take, and cut these forms out of a block of cardboard or foam core. Cover the forms with Velcro. Next, get a collection of objects that can serve as widgets (buttons, knobs, dials, and so on), and attach the other side of the Velcro to them. Now, you can configure the idea in a variety of possible representations. Feel free to use basic foam or plastic models (soaps), along with stickers, markers, or images.

2. Build and iterate: As you work your way through various iterations of the product being mocked-up, document why you’re making changes. This is important because, at some point, you may want to go back to a previous version.

• Using your storyboard and initial mock-ups, create a video showing how a person interacts with your solution with enough clarity to be understood by others.

• Use a video camera or a point-and-shoot camera with video capabilities.

• Use iMovie or Windows Movie Maker for the video editing.

• Keep it simple and quick.

At this stage of the process, you’ve tested your ideas with prospective end users, selected a direction to refine, and prototyped it into a single, disruptive solution. To take that solution to the next level, you’ll have to make a disruptive pitch that will persuade internal and/or external stakeholders to invest in or adopt what you’ve created. That’s the focus of Chapter 5.